Abstract

Purpose of Review

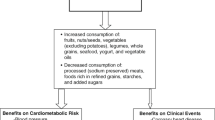

Mediterranean diet (MD) has been inversely linked with insulin resistance and diabetes, while inflammation is recognized as a common denominator in cardiometabolic disorders. Here, we review the synergistic effect between MD and inflammation, the anti-inflammatory properties of core MD components, and the possible biological mechanisms linking nutrients with inflammation.

Recent Findings

MD is abundant in anti-inflammatory foods, like whole grains, fruits and vegetables, wine, olive oil, nuts, and fish. This results in a high intake of various polyphenols, as well as high unsaturated/saturated and n3/n6 fatty acid ratios, leading through different mechanisms, such as oxidative stress reduction, alteration of NF-κB, PPAR-γ pathways, prebiotic function on gut microbiota, and others, to an attenuation of inflammation state.

Summary

MD is comprised by a plethora of foods, with anti-inflammatory potential, so its observed anti-diabetic effect could, at least partially, be ascribed to an attenuation of inflammation state.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Keys A, et al. The diet and 15-year death rate in the seven countries study. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124(6):903–15.

Koloverou E, et al. The effect of Mediterranean diet on the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of 10 prospective studies and 136,846 participants. Metabolism. 2014;63(7):903–11.

Psaltopoulou T, et al. Mediterranean diet, stroke, cognitive impairment, and depression: a meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(4):580–91.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Med. 2015;4(12):1933–47.

Willett WC, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid: a cultural model for healthy eating. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(6 Suppl):1402S–6S.

UNESCO. Representative list of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/mediterranean-diet-00884 2010.

Bach-Faig A, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(12A):2274–84.

Trichopoulou A, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2599–608.

Estruch R, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1279–90.

Salas-Salvado J, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):14–9.

Koloverou E, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and 10-year incidence (2012–2014) of diabetes: correlations with inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers in the ATTICA cohort study Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(1):73–81.

Panagiotakos DB, et al. Exploring the path of Mediterranean diet on 10-year incidence of cardiovascular disease: the ATTICA study (2002-2012). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25(3):327–35.

Garcia M, et al. The effect of the traditional Mediterranean-style diet on metabolic risk factors: a meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2016;8(3):168.

Kastorini CM, et al. The effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components: a meta-analysis of 50 studies and 534,906 individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(11):1299–313.

Huo R, et al. Effects of Mediterranean-style diet on glycemic control, weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors among type 2 diabetes individuals: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(11):1200–8.

Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(2):98–107.

Montecucco F, et al. The role of inflammation in cardiovascular outcome. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2017;19(3):11.

Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1793–801.

Torres-Leal F, et al. Adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. Insulin Resistance, ed. D.S. Arora. 2012: InTech. https://www.intechopen.com/books/insulinresistance/adipose-tissue-inflammation-and-insulin-resistance

Cawthorn WP, Sethi JK. TNF-alpha and adipocyte biology. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(1):117–31.

Karpe F, Dickmann JR, Frayn KN. Fatty acids, obesity, and insulin resistance: time for a reevaluation. Diabetes. 2011;60(10):2441–9.

Wang X, et al. Inflammatory markers and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(1):166–75.

Guilherme A, et al. Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(5):367–77.

Queiroz JC, et al. Control of adipogenesis by fatty acids. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2009;53(5):582–94.

Harman-Boehm I, et al. Macrophage infiltration into omental versus subcutaneous fat across different populations: effect of regional adiposity and the comorbidities of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(6):2240–7.

Muris DM, et al. Microvascular dysfunction is associated with a higher incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(12):3082–94.

Muniyappa R, Sowers JR. Role of insulin resistance in endothelial dysfunction. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2014;14(1):5–12.

Davignon J, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109(23 Suppl 1):III27–32.

Rubbo H, et al. Interactions of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite with low-density lipoprotein. Biol Chem. 2002;383(3–4):547–52.

Steinberg D, Witztum JL. Is the oxidative modification hypothesis relevant to human atherosclerosis? Do the antioxidant trials conducted to date refute the hypothesis? Circulation. 2002;105(17):2107–11.

Hulsmans M, Holvoet P. The vicious circle between oxidative stress and inflammation in atherosclerosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14(1–2):70–8.

Ridker PM, Luscher TF. Anti-inflammatory therapies for cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(27):1782–91.

Kaptoge S, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and risk of coronary heart disease: new prospective study and updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(9):578–89.

Fung TT, et al. Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1):163–73.

Ambring A, et al. Mediterranean-inspired diet lowers the ratio of serum phospholipid n-6 to n-3 fatty acids, the number of leukocytes and platelets, and vascular endothelial growth factor in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(3):575–81.

Esposito K, et al. Effect of weight loss and lifestyle changes on vascular inflammatory markers in obese women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1799–804.

Panagiotakos DB, et al. Association between the prevalence of obesity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet: the ATTICA study. Nutrition. 2006;22(5):449–56.

Estruch R, et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on cardiovascular risk factors: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(1):1–11.

Urpi-Sarda M, et al. The Mediterranean diet pattern and its main components are associated with lower plasma concentrations of tumor necrosis factor receptor 60 in patients at high risk for cardiovascular disease. J Nutr. 2012;142(6):1019–25.

Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Mediterranean dietary pattern, inflammation and endothelial function: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24(9):929–39.

Marin C, et al. Mediterranean diet reduces endothelial damage and improves the regenerative capacity of endothelium. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(2):267–74.

Gomez-Delgado F, et al. Polymorphism at the TNF-alpha gene interacts with Mediterranean diet to influence triglyceride metabolism and inflammation status in metabolic syndrome patients: From the CORDIOPREV clinical trial. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58(7):1519–27.

Katcher HI, et al. The effects of a whole grain-enriched hypocaloric diet on cardiovascular disease risk factors in men and women with metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(1):79–90.

Qi L, et al. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load, cereal fiber, and plasma adiponectin concentration in diabetic men. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(5):1022–8.

Mantzoros CS, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern is positively associated with plasma adiponectin concentrations in diabetic women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):328–35.

Jensen MK, et al. Whole grains, bran, and germ in relation to homocysteine and markers of glycemic control, lipids, and inflammation 1. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):275–83.

Widmer RJ, et al. The Mediterranean diet, its components, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2015;128(3):229–38.

Hermsdorff HH, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and proinflammatory gene expression from peripheral blood mononuclear cells in young adults: a translational study. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2010;7:42.

Bhupathiraju SN, Tucker KL. Greater variety in fruit and vegetable intake is associated with lower inflammation in Puerto Rican adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(1):37–46.

Calder PC, et al. Dietary factors and low-grade inflammation in relation to overweight and obesity. Br J Nutr. 2011;106(Suppl 3):S5–78.

Schwingshackl L, Christoph M, Hoffmann G. Effects of olive oil on markers of inflammation and endothelial function—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2015;7(9):7651–75.

Calabriso N, et al. Extra virgin olive oil rich in polyphenols modulates VEGF-induced angiogenic responses by preventing NADPH oxidase activity and expression. J Nutr Biochem. 2015;28:19–29.

Jiang R, et al. Nut and seed consumption and inflammatory markers in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(3):222–31.

Mukuddem-Petersen J, et al. Effects of a high walnut and high cashew nut diet on selected markers of the metabolic syndrome: a controlled feeding trial. Br J Nutr. 2007;97(6):1144–53.

Sari I, et al. Effect of pistachio diet on lipid parameters, endothelial function, inflammation, and oxidative status: a prospective study. Nutrition. 2010;26(4):399–404.

Banel DK, Hu FB. Effects of walnut consumption on blood lipids and other cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(1):56–63.

Ros E. Nuts and novel biomarkers of cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1649S–56S.

Chrysohoou C, et al. Effects of chronic alcohol consumption on lipid levels, inflammatory and haemostatic factors in the general population: the ‘ATTICA’ study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2003;10(5):355–61.

Beulens JW, et al. Alcohol consumption, mediating biomarkers, and risk of type 2 diabetes among middle-aged women. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(10):2050–5.

Blanco-Colio LM, et al. Red wine intake prevents nuclear factor-kappaB activation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy volunteers during postprandial lipemia. Circulation. 2000;102(9):1020–6.

van Bussel BC, et al. Alcohol and red wine consumption, but not fruit, vegetables, fish or dairy products, are associated with less endothelial dysfunction and less low-grade inflammation: the Hoorn study. Eur J Nutr. 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1420-4.

Liu K, et al. Effect of resveratrol on glucose control and insulin sensitivity: a meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr, 2014;99(6):1510–9

Turunen AW, et al. Fish consumption, omega-3 fatty acids, and environmental contaminants in relation to low-grade inflammation and early atherosclerosis. Environ Res. 2013;120:43–54.

Cormier H, et al. Expression and sequence variants of inflammatory genes; effects on plasma inflammation biomarkers following a 6-week supplementation with fish oil. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(3):375.

Lin N, et al. What is the impact of n-3 PUFAs on inflammation markers in type 2 diabetic mellitus populations?: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15:133.

Clarke SD. The multi-dimensional regulation of gene expression by fatty acids: polyunsaturated fats as nutrient sensors. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2004;15(1):13–8.

Staiger H, et al. Fatty acid-induced differential regulation of the genes encoding peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha and -1beta in human skeletal muscle cells that have been differentiated in vitro. Diabetologia. 2005;48(10):2115–8.

Kim JK. Fat uses a TOLL-road to connect inflammation and diabetes. Cell Metab. 2006;4(6):417–9.

Fazzari M, et al. Olives and olive oil are sources of electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkenes. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84884.

Freeman BA, et al. Nitro-fatty acid formation and signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(23):15515–9.

Imamura F, et al. Effects of saturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate on glucose-insulin homeostasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled feeding trials. PLoS Med. 2016;13(7):e1002087.

Schroder H. Protective mechanisms of the Mediterranean diet in obesity and type 2 diabetes. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;18(3):149–60.

Calder PC. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: New twists in an old tale. Biochimie. 2009;91(6):791–5.

•• Scoditti E, et al. Vascular effects of the Mediterranean diet-Part II: role of omega-3 fatty acids and olive oil polyphenols. Vascul Pharmacol. 2014;63(3):127–34. This paper provides a comprehensive discussion of the effects of n3 fatty acids and olive oil polyphenols on inflammatory processes.

Johnson GH, Fritsche K. Effect of dietary linoleic acid on markers of inflammation in healthy persons: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(7):1029–41. 1041 e1–15

Harris WS. The omega-6/omega-3 ratio and cardiovascular disease risk: uses and abuses. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2006;8(6):453–9.

Godos J, et al. Dietary sources of polyphenols in the Mediterranean healthy eating, aging and lifestyle (MEAL) study cohort. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2017:1–7.

Sun B, et al. Fractionation of red wine polyphenols by solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2006;1128(1–2):27–38.

Joseph SV, Edirisinghe I, Burton-Freeman BM. Fruit polyphenols: a review of anti-inflammatory effects in humans. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;56(3):419–44.

Manach C, et al. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(5):727–47.

Basli A, et al. Wine polyphenols: potential agents in neuroprotection. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2012;2012:805762.

Covas MI, et al. The effect of polyphenols in olive oil on heart disease risk factors: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(5):333–41.

Moreno-Luna R, et al. Olive oil polyphenols decrease blood pressure and improve endothelial function in young women with mild hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25(12):1299–304.

Lucas L, Russell A, Keast R. Molecular mechanisms of inflammation. Anti-inflammatory benefits of virgin olive oil and the phenolic compound oleocanthal. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(8):754–68.

Forman HJ, Davies KJ, Ursini F. How do nutritional antioxidants really work: nucleophilic tone and para-hormesis versus free radical scavenging in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;66:24–35.

• Crasc IL, et al. Natural antioxidant polyphenols on inflammation management: anti-glycation activity vs metalloproteinases inhibition. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr, 2016: p. 0. This paper presents a novel anti-inflammatory mechanism of polyphenols through inhibition of AGEs at different levels of the glycation process.

• Cueva C, et al. An integrated view of the effects of wine polyphenols and their relevant metabolites on gut and host health. Molecules, 2017. 22(1). This paper discusses the prebiotic effect of wine polyphenols on gut microbiota, suggesting a novel link between polyphenol and inflammation.

de Vos WM, Nieuwdorp M. Genomics: a gut prediction. Nature. 2013;498(7452):48–9.

Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C. Inclusion of dietary evaluation in cardiovascular disease risk prediction models increases accuracy and reduces bias of the estimations. Risk Anal. 2009;29(2):176–86.

Maestre R, et al. Alterations in the intestinal assimilation of oxidized PUFAs are ameliorated by a polyphenol-rich grape seed extract in an in vitro model and Caco-2 cells. J Nutr. 2013;143(3):295–301.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Efi Koloverou and Demosthenes B. Panagiotakos declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does contain studies with human subjects performed by any of the authors. For these studies, informed consent had been provided.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cardiovascular Disease

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koloverou, E., Panagiotakos, D.B. Inflammation: a New Player in the Link Between Mediterranean Diet and Diabetes Mellitus: a Review. Curr Nutr Rep 6, 247–256 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-017-0209-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-017-0209-7