Abstract

Introduction

Risankizumab has been approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis; however, real-life data are limited. Our objectives were to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of risankizumab and its impact on the quality of life of patients with psoriasis in a real-world setting.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 154 patients from 18 centers in the Czech Republic who had undergone biologic therapy with risankizumab for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Baseline characteristics included data on comorbidities, demographics, previous therapies, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score, and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score. The proportion of patients achieving a 90% improvement in their PASI score from baseline (PASI 90) and complete resolution (PASI 100) after 16, 28, and 52 weeks was analyzed.

Results

A total of 95 men and 59 women with mean body mass index (BMI) of 29.6 were enrolled in our analysis. The mean age of the patients was 48.5 years and the mean time from diagnosis until initiation of risankizumab therapy was 22.5 years. After 16 weeks, 63.8 and 44.7% patients achieved PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses, respectively. Improvement continued with time, and the proportion of patients with PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses increased to 82.4 and 67.6%, respectively, at week 52. A significant reduction was observed over time in the DLQI. Patients achieving PASI 100 response at week 16 had a higher reduction in the DLQI score than those with PASI 90 response (− 15.9 vs. − 11.8). PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses were independent of the BMI and previous biologic therapy. No new safety issues were identified.

Conclusions

In this patient population, risankizumab was effective and safe in a real-world setting, and a high number of patients achieved PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses. A higher reduction in the DLQI was seen in patients with PASI 100 response, which supports the evidence that this value should be the new therapeutic goal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Risankizumab has been approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Double-blind randomized placebo controlled trials have shown high efficacy, but real world-data are scarce. |

This multicenter study presents the real-life experience of 154 patients initiating risankizumab therapy who were followed up to 52 weeks. |

Real-life data include patients with co-morbidities who are standardly excluded from enrolling in registration clinical trials. |

What was learned from the study? |

Risankizumab is effective and well tolerated in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis in a real-world setting. |

PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses were independent of body mass index and previous biologic therapy. |

The reduction in the DLQI score was more significant in the PASI 100 group than in the PASI 90 group. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14610570.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory skin disease with an estimated prevalence of 2% in adults [1, 2]. In the last decade, psoriasis has been associated with different conditions, including obesity, arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia, all of which are components of metabolic syndrome [3]. Although not a life-threatening disease, psoriasis has a major impact on the quality of life of patients [4]. Treatment needs to be highly effective and safe, which is achievable through biologic therapy [5]. A 90% improvement in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 90) from baseline has become the new treatment goal following the introduction of new molecules targeting interleukin (IL)-17 and more recently IL-23 [6].

The newest available biologic is risankizumab, a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds the subunit of IL-23 [7]. High levels of efficacy and safety have been demonstrated in different clinical trials (UltIMMa-1, UltIMMa-2, IMMvent, IMMerge [8,9,10]). In these studies, a high number of patients achieved PASI 90 and PASI 100 (complete remission) responses (PASI 90 in 75.3% of the patients at week 16 in the UltIMMA-1 trial and PASI 100 in 59.5% of the patients at week 52 in the UltIMMA-2 trial) [9].

Patients included in registration clinical trials are often dissimilar to those seen in daily clinical practice due to the strict exclusion criteria of the former, including washout period for previous biologic therapy. Real-world evidence provides valuable information for a better understanding of the attributes of different biologics in different patients. Published real-life data on risankizumab are limited to studies with small sample size and short follow-up that consider the novelty of the drug [11, 12].

The purpose of our study was to assess the effectiveness and safety of risankizumab and its impact on the quality of life of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis in the Czech Republic.

Methods

This was a retrospective multicenter study with the aim of analyzing data on adult patients treated with risankizumab for moderate-to-severe psoriasis at 18 centers in the Czech Republic compiled in the BIOREP registry. BIOREP is a web-based database of patients with psoriasis treated with biologics or targeted therapy in the Czech Republic and is one of the first such registeries in Central and Eastern Europe. The BIOREP database records demographic data, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores, PASI score, comorbidities, and the efficacy and safety of the drugs used. The registry was started in May 2005 (updated in 2011 and 2018) and is supervised by the Czech Dermatovenereology Society. In the Czech Republic, biologic therapy is administered in 29 specialized centers, and all patients treated with biologics in 27 of the 29 centers are included in the registry. At the time of this study, risankizumab was being administered in 18 centers in the Czech Republic.

We included every patient who received at least one dose of risankizumab 150 mg administered subcutaneously. The cutoff date for our analysis was 7 January 2021. Biologic (bio)-naïve (risankizumab administered as first-line biologic) and bio-experienced (previous exposure to one or more biologic drugs) patients were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and all subsequent amendments, and all patients provided written informed consent. Patient-level data used for this analysis were de-identified, and Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study. Permission to access/use data from BIOREP registry was obtained.

At the baseline visit, demographic data (age, sex, weight, height, body mass index [BMI]) and data on comorbidities, medical history, smoking status, and previous systemic and biologic therapy were obtained. In addition, the age at onset of psoriasis and age at onset of risankizumab therapy were recorded. Before initiation of therapy, we screened patients for hepatitis B and C and for latent tuberculosis.

Data on PASI and DLQI scores and on adverse events were collected during patient visits at weeks 16, 28, and 52 when risankizumab was administered. We focused on the PASI 90 and PASI 100, respectively) and categorized our patients according to previous biologic therapy and BMI (< 25 and ≥ 25 kg/m2). The DLQI was used to assess the improvement in the quality of life in combination with a reduction in the PASI score. We compared the numerical change in the DLQI score of patients who achieved PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses.

Statistical Analysis

For the purposes of this analysis, epidemiological data (i.e., demographic and disease characteristics and medical history), disease severity (PASI, DLQI), BMI, comorbidities, and previous treatments were summarized using descriptive statistics. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the dataset based on the number of patients and their percentage proportion in groups relative to categorical variables; the mean and standard deviation (SD) were used for continuous variables.

Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when needed, while continuous variables were tested using the Mann–Whitney U test (Wilcoxon rank sum test). P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Core Team 2019).

Results

Patient Demographics and Previous Treatments

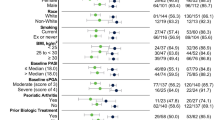

A total of 154 patients (95 men and 59 women) with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, with mean (± SD) disease duration of 22.8 ± 13.4 years, were enrolled in this study. The mean age of the patients at the time risankizumab therapy was initiated was 48.2 ± 13.1 years. At baseline, the mean BMI of the patients was 29.6 ± 6.2, and 79.9% were overweight (BMI ≥ 25). Fifty-eight patients (37.7%) were obese (BMI ≥ 30). More than half of the patients (61.0%) had at least one comorbidity, with metabolic (50.0%) and cardiovascular (46.8%) diseases being the most common. Thirty-two patients (20.8%) had psoriatic arthritis at the start of risankizumab treatment. Three patients had previous malignancy (malignant fibrous histiocytoma with nodal infiltration diagnosed 15 years before initiation of risankizumab, MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) lymphoma and malignant melanoma diagnosed 3 and 6 years, respectively, before risankizumab therapy). Of the 154 patients, 39.6% were smokers and 22.7% were ex-smokers. Previous therapy consisted of phototherapy (85.7% of patients) and treatment with methotrexate (85.1%), retinoids (72.7%), and cyclosporine (40.3%), respectively. Bio-naïve and bio-experienced patients constituted 38.3 and 61.7% of the patient population (32.5% had been treated in the past with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNFα], 6.5% with anti-interleukin [IL]-12/23, 13% with anti-IL-17, and 9.7% with apremilast), respectively. The mean PASI score at baseline was 16.7 ± 7.0, with the highest score being 45.5. Thirty-three patients (21.4%) had nail involvement and seven (4.5%) had inverse psoriasis. Quality of life was impaired before the initiation of therapy with an average DLQI score of 14.9 ± 6.5 (Table 1).

Risankizumab Treatment

All patients received at least one dose of risankizumab. At the time of the analysis, 94, 66, and 34 patients had completed week 16, week 28, and week 52 of treatment, respectively. The mean (± SD) PASI score fell from 16.7 ± 7.0 at baseline to 1.7 ± 2.3 after 16 weeks of risankizumab treatment. A further reduction in the mean PASI score was observed after 28 weeks (1.1 ± 1.9) and after 1 year of therapy (0.9 ± 2.3) (Fig. 1). The PASI 90 response was rapidly achieved after just 16 weeks of risankizumab treatment in 63.8% of the patients, increasing further after 28 weeks to 77.3% and reaching 82.4% of patients after 52 weeks of therapy. The PASI 100 response was observed in 42 (44.7%), 39 (59.1%), and 23 (67.6%) of patients after 16, 28, and 52 weeks of therapy, respectively (Fig. 2). Absolute PASI scores of ≤ 3 and ≤ 1 were achieved in 73 (77.7%) and 53 (56.4%) patients at week 16, in 58 (87.9%) and 48 (72.7%) patients at week 28, and in 30 (88.2%) and 27 (79.4%) patients at week 52, respectively (Fig. 3).

Our analysis showed that previous biologic therapy did not have a negative impact on the PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses. Of all bio-naïve patients, 17.9% demonstrated PASI 90 responses after 4 months of therapy compared to 21.1% of bio-experienced patients (P > 0.05). Similar results were obtained for the PASI 100 response, which was achieved in 42.9% of patients in the bio-naïve group and 47.4% in the bio-experienced group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4a). Higher BMI was not associated with worse results in terms of achieving PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses. At week 16 of therapy, an improvement of at least 90% was seen in 57.1% of the patients with BMI < 25 and in 65.8% of those with BMI > 25 (P > 0.05). Complete clearance (PASI1 00) was observed in 38.1% of the patients with BMI < 25 and in 46.6% of those with BMI ≥ 25 (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4b).

The mean (± SD) DLQI score at baseline was 14.9 ± 6.5, which decreased to 2.1 ± 3.2 after 16 weeks, to 1.0 ± 1.9 after 28 weeks, and to 0.5 ± 1.1 after 52 weeks of therapy (Fig. 5a). We compared changes in the DLQI scores between patients with PASI 90 and PASI 100 response. At week 16, patients who achieved PASI 100 response had a greater reduction in the DLQI than those with PASI 90 response. In the PASI 100 group, DLQI decreased by 15.9 points compared to 11.8 in the PASI 90 group (P = 0.033) (Fig. 5b).

During the study period, four adverse events led to discontinuation of the drug. Three patients had a permanent discontinuation and one patient temporarily interrupted the therapy due to mild COVID-19 infection; however, the application was postponed until the patient did not show any symptoms of COVID-19. Permanent discontinuation was due to colorectal cancer in one patient and due to morbus Morbihan in the second patient since the treating physician could not rule out an association with risankizumab. The third patient was a primary non-responder.

Discussion

The results of this multicenter retrospective study demonstrate the effectiveness and safety of risankizumab in a real-world setting. The patient population analyzed was registered in the Czech Republic registry for biological treatment (BIOREP).

Analysis of the demographic data showed a high percentage of overweight patients and a high mean onset age at the initiation of therapy, which corresponds to the general psoriatic population in BIOREP [13]. A relatively high number of patients in this real-life study were bio-naïve (38.3%), even though risankizumab is the newest of a number of biologics registered for the treatment of psoriasis. This can be explained by the fact that physicians would prefer to initiate biologic therapy with a known drug demonstrating a high response rate, as it has been shown that patients achieving PASI 100 response have a higher chance of remaining stable during the treatment [14].

The reduction in the PASI and DLQI scores was significant. After 16 weeks, 63.8% of the patients achieved the PASI 90 response, further increasing after 28 weeks to 77.3% and reaching 82.4% after 1 year of therapy. The PASI 90 response was lower in our study (63.8%) after 4 months compared to the results of the UltIMMa-1 (75.3%) and UltIMMa-2 (74.8%) trials [9]. Similar lower results in PASI 90 response in real life have been reported by Hansel et al. (63.2%) who analyzed 57 patients treated with risankizumab. [12]. After 52 weeks, our results were comparable with those of the UltIMMa-1 and -2 trials, as 82.4% of our patients achieved PASI 90 response compared to 81.9 and 80.6% of the patients in these clinical trials, respectively [9]. This result indicates that in real life, the onset of risankizumab therapy could be slightly slower than that in the registration studies; possibly explanations for this difference include previous biologic therapy, high BMI, or a combination of these. The PASI 100 response was observed in 42 (44.7%) patients after 16 weeks and in 23 (67.6%) patients after 52 weeks; this proportion of patients is higher than that achieving the PASI 100 score in the UltMMA-2 phase 3 trial (59.5%) and similar to that reported the real-life study by Hansel et al. [8, 9, 12,]. It is necessary to emphasize that the number of included patients in the above-mentioned phase 3 trials was much higher the number in our study [9].

The mean (± SD) PASI score fell from 16.7 ± 7.0 to 1.7 ± 2.3 after 4 months, which is similar and marginally better than the mean PASI score reported in a study involving eight patients treated with risankizumab in an Italian center (mean PASI score after 16 weeks 3.3 ± 1.7). The patients in the Italian study had undergone several biologic therapies before risankizumab, without success, which means that they represented difficult-to-treat cases, which could be the reason for a marginally higher reduction in mean PASI score in our study [11]. A similar reduction of PASI score in a real-life setting was described by Megna et al. and also by Ruggiero et al., who indirectly compared risankizumab with guselkumab [15, 16].

Absolute PASI scores of ≤ 3 and ≤ 1 were achieved in 73 (77.7%) and 53 (56.4%) of patients at week 16, in 58 (87.9%) and 48 (72.7%) patients at week 28, and in 30 (88.2%) and 27 (79.4%) patients at week 52, respectively. An absolute PASI score of < 3 is suggested as the target of therapy in the new French guidelines for the treatment of psoriasis [17].

More than half of our patients (61.7%) had previously undergone biologic treatment, which is much higher than the patient population in the UltIMMA-1 (34%), UltIMMA-2 (40%), and IMMvent (32%) trials [8,9,10]. This is typical for real-life data because in real life the newest biologic therapy is usually initiated only in difficult cases, such as when the patient does not respond adequately to previous biologic therapy, and the cost of therapy versus treatment with older drugs (mainly biosimilars) is taken into account. Moreover, in clinical trials, the washout period for biologics is long, which makes it difficult to randomize bio-experienced patients. Even though we had a higher percentage of bio-experienced patients (vs. bio-naïve patients), we did not see any negative impact of previous treatment with biologics on the effectiveness of risankizumab.

The average (± SD) BMI at the baseline visit was 29.6 ± 6.2, which is similar to that reported in the IMMvent trial (30.2 ± 7.9) [8]. We did not observe differences in achieving PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses between patients in the groups with BMI < 25 and ≥ 25. This is in contrast to the results reported by Hansel et al., wherein overweight and obese patients experienced a worse outcome. More data are necessary to conclude if BMI > 25 could be a negative predictor for treatment success with risankizumab, together with a subanalysis of combination factors, such as overweight with previous exposure to biologics.

Psoriasis has a well-known negative impact on the quality of life of patients, even if only residual lesions remain in the skin. Patients achieving PASI 100 response have a higher chance of achieving DLQI 0/1 than those with PASI90 response. Complete and long-term clearance is considered to be the ideal treatment target [18,19,20]. Our patients showed a significant decrease in the DLQI score during risankizumab therapy, and our data support the evidence that patients achieving PASI 100 response have a better quality of life than those having PASI 90 response. The DLQI score had decreased by 15.9 points at week 16 compared to the baseline visit in the PASI 100 group versus 11.8 points in the PASI 90 group.

The safety profile of risankizumab in our real-life patients was similar to that reported in clinical trials [9]. No new safety signals were observed. One patient developed colorectal carcinoma, and therapy was discontinued until the oncologist could decide on the patient‘s treatment. One patient with known rosacea was diagnosed with morbus Morbihan, and the treating physician decided to stop the therapy and switch to an anti-IL-17 drug. New information was not provided regarding improvement in morbus Morbihan after discontinuation of risankizumab. One patient was infected with SARS-CoV-2, and therapy was interrupted and re-initiated after 3 days of asymptomatic status; the COVID-19 infection was considered to be mild in this patient.

The limitations of this study are its retrospective design and the absence of a control group, which is typical for real-world data. In addition, the number of participants is not very high; however, up to the time of submission of this paper, our study reports data on the largest real-world population treated with risankizumab.

Conclusion

In our study, risankizumab showed a high efficacy and a good safety profile. Real-life data support the evidence from clinical trials and add information that was not addressed during the registration studies, such as the DLQI decrease in the patient cohorts achieved PASI 90 and PASI 100 scores, respectively. We observed that a marginally lower number of patients achieved PASI 90 response at week 16 in our study compared to the earlier trials; however, after 1 year of therapy, the percentage was the same. Interestingly, complete clearance was observed in a higher number of patients in our study than in the trials. Higher BMI and previous biologic therapy did not have a negative impact on the efficacy of the drug. Quality of life improved with PASI 100 response, which had a higher impact on improvement.

References

Parisi R, Iskandar IYK, Kontopantelis E, et al. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1590.

Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–94.

Sondermann W, Djeudeu Deudjui DA, Körber A, et al. Psoriasis, cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic disorders: sex-specific findings of a population-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(4):779–86.

Mattei PL, Corey KC, Kimball AB. Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): the correlation between disease severity and psychological burden in patients treated with biological therapies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(3):333–7.

Kim HJ, Lebwohl MG. Biologics and psoriasis: the beat goes on. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37(1):29–36.

Puig L. PASI90 response: the new standard in therapeutic efficacy for psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(4):645–8.

Strober B, Menter A, Leonardi C, et L. Efficacy of risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis by baseline demographics, disease characteristics and prior biologic therapy: an integrated analysis of the phase III UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2 studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):2830–8.

Reich K, Gooderham M, Thaçi D, et al. Risankizumab compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (IMMvent): a randomised, double-blind, active-comparator-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10198):576–86.

Gordon KB, Strober B, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and ustekinumab-controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10148):650–61.

Warren RB, Blauvelt A, Poulin Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab vs. secukinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (IMMerge): results from a phase III, randomized, open-label, efficacy-assessor-blinded clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(1):50–9.

Megna M, Fabbrocini G, Ruggiero A, Cinelli E. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in psoriasis patients who failed anti-IL-17, anti-12/23 and/or anti IL-23: preliminary data of a real-life 16-week retrospective study. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):

Hansel K, Zangrilli A, Bianchi L, et al. A multicenter study on effectiveness and safety of risankizumab in psoriasis: an Italian 16-week real-life experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(3):e169-70.

Kojanova M, Fialova J, Cetkovska P, et al. Characteristics and risk profile of psoriasis patients included in the Czech national registry BIOREP and a comparison with other registries. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(4):428–34.

Adenubiova E, Arenberger P, Gkalpakioti P, et al. Psoriasis treatment with adalimumab in clinical practice: long-term experience in a center for biological therapy in the Czech Republic. J Dermatol Treat. 2018;29(6):579–82.

Megna M, Cinelli E, Gallo L, Camela E, Ruggiero A, Fabbrocini G. Risankizumab in real life: preliminary results of efficacy and safety in psoriasis during a 16-week period. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-021-02200-7.

Ruggiero A, Fabbrocini G, Cinelli E, Megna M. Guselkumab and risankizumab for psoriasis: a 44-week indirect real-life comparison. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;S0190–9622(21):00170–5. .

Amatore F, Villani AP, Tauber M, Viguier M, Guillot B, Psoriasis Research Group of the French Society of Dermatology. French guidelines on the use of systemic treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(3):464–83.

Puig L, Thom H, Mollon P, Tian H, Ramakrishna GS. Clear or almost clear skin improves the quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):213–20.

Strober B, Papp KA, Lebwohl M, et al. Clinical meaningfulness of complete skin clearance in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(1):77–82.

Takeshita J, Callis Duffin K, Shin DB, et al. Patient-reported outcomes for psoriasis patients with clear versus almost clear skin in the clinical setting. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(4):633–41.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all of the dermatologists and collaborators who participated in the creation of BIOREP for their efforts and dedication to the project.

BIOREP Study Group Members

The members of the BIOREP Study Group are (in alphabetical order of last name): Zdenek Antal, Jirina Bartonova, Alzbeta Bezvodova, Linda Blahova, Petra Brodska, Hana Buckova, Dominika Diamantova, Hana Duchkova, Olga Filipovska, Petra Gkalpakioti, Martina Grycova, Jiri Horazdovsky, Eva Horka, Eduard Hrncir, Jaromira Janku, Renata Kopova, Dora Kovandova, Iva Lomicova, Romana Machackova, Alena Machovcova, Hana Malikova, Martina Matzenauer, Miroslav Necas, Helena Nemcova, Radka Neumannová, Jitka Osmerova, Veronika Pallova, Blanka Pinkova, Zuzana Plzakova, Marie Policarova, Tomas Pospisil, Miloslav Salavec, Veronika Slonkova, Ivana Strouhalova, David Stuchlik, Alena Stumpfova, Jaroslav Sevcik, Jan Sternbersky, Jirí Stork, Katerina Svarcova, Katerina Tepla, Martin Tichy, Hana Tomkova, Yvetta Vantuchova, Vladimir Vasku, Ivana Vejrova.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Martina Kojanova, Petra Cetkovska, Spyridon Gkalpakiotis, Monika Arenbergerova, Petr Arenberger, Jorga Fialova, and Tomas Dolezal have served as consultants, speakers, or investigators for Abbvie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Barbora Velackova declares that she has nothing to dislcose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and all subsequent amendments, and all patients provided written informed consent. Patient-level data used for this analysis were de-identified, and Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study. Permission to access/use data from BIOREP registry was obtained.

Data Availability

The datasets generated analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

The members of the BIOREP study group are listed in Acknowledgements.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gkalpakiotis, S., Cetkovska, P., Arenberger, P. et al. Risankizumab for the Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis: Real-Life Multicenter Experience from the Czech Republic. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 11, 1345–1355 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00556-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00556-2