Abstract

Racial disparities in education in Brazil (and elsewhere) are well documented. Because this research typically examines educational variation between individuals in different families, however, it cannot disentangle whether racial differences in education are due to racial discrimination or to structural differences in unobserved neighborhood and family characteristics. To address this common data limitation, we use an innovative within-family twin approach that takes advantage of the large sample of Brazilian adolescent twins classified as different races in the 1982 and 1987–2009 Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios. We first examine the contexts within which adolescent twins in the same family are labeled as different races to determine the characteristics of families crossing racial boundaries. Then, as a way to hold constant shared unobserved and observed neighborhood and family characteristics, we use twins fixed-effects models to assess whether racial disparities in education exist between twins and whether such disparities vary by gender. We find that even under this stringent test of racial inequality, the nonwhite educational disadvantage persists and is especially pronounced for nonwhite adolescent boys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This emphasis on skin color over racial identity is partly due to the multifaceted racial ancestry of most Brazilians. For much of the colonial period, white men outnumbered white women, yielding high levels of miscegenation between white men and nonwhite females (Telles 1995).

Monozygotic (MZ) twins would be the ideal analytical sample for this study because they share genetic characteristics and are of the same sex. Thus, twins fixed-effects models using a sample of MZ twin pairs would control for not only shared observed and unobserved family and neighborhood factors, as is the case in the current analytic sample of same-sex twins, but also for shared genetic characteristics that could potentially affect race labeling. Following past studies with lack of information on zygosity, we used the Weinberg method (Conley et al. 2006a, b; Torche and Echevarría 2011) to estimate a race effect on education for MZ twins. This method accurately estimates the number of MZ twins in the sample, therefore yielding an estimated race coefficient for MZ twins, for whom there is no issue of confounding zygosity or gender. Using the Weinberg method and the parameter estimates of our models, we obtained weighted race coefficients (available upon request) for MZ twins in all families that are consistent with the results presented here.

An issue with using household data to determine children’s relationships also found in previous research is that we may be missing children living outside the household (Cáceres-Delpiano 2006; Conley and Glauber 2006; Marteleto 2012). We may therefore be missing twin pairs if one sibling lives in the household and the other does not. One way to determine the severity of this problem is to compare a measure of number of siblings based on mother’s reports of their number of living children with the count measure we constructed using the household roster. We find a 94 % concordance rate between the count measure and the report measure provided by the PNAD. Although this measure does not provide information on twins, it assures us that we are not missing a large portion of siblings living outside the household, at least for 12- to 18-year-olds.

Exceptions are the 1982 and 1996 PNADs, for which a special module on social mobility was implemented.

In most cases, the household head or the spouse of the head is the respondent of the questionnaire (Telles 2004). Because the analytical sample in this study is composed of children of the head of the family, in most cases, one of the parents of the children examined identifies the child’s race.

References

Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Alves, J. E. D., & Corrêa, S. (2009). Igualdade e desigualdade de gênero no Brasil: Um panorama preliminar, 15 anos depois do Cairo [Gender equality and inequality in Brazil: A preliminary overview, 15 years after Cairo]. Brasil, 15, 121–223.

Bailey, S. R. (2008). Unmixing for race making in Brazil. American Journal of Sociology, 114, 577–614.

Bailey, S. (2009). Legacies of race: Identities, attitudes, and politics in Brazil. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Barros, R., & Lam, D. (1996). Income and educational inequality and children’s schooling attainment. In N. Birdsall & R. Sabot (Eds.), Opportunity foregone: Education in Brazil (pp. 337–366). Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Becker, G. S. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Behrman, J. R., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (2004). Returns to birthweight. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86, 586–601.

Beltrão, K. I., & Novellino, M. S. (2002). Alfabetização por raça e sexo no Brasil: Evolução no período 1940–2000 [Literacy by race and sex in Brazil: Evolution in the period 1940–2000] (ENCE Texto para Disucssão No. 1). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Escola Nacional de Ciências Estatísticas.

Cáceres-Delpiano, J. (2006). The impacts of family size on investment in child quality. Journal of Human Resources, 41, 738–754.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46.

Cohen, J. (1968). Weighed kappa: Nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychological Bulletin, 70, 213–220.

Conley, D. (2008). Bringing sibling differences in: Enlarging our understanding of the transmission of advantage in families. In A. Lareau & D. Conley (Eds.), Social class: How does it work? (pp. 179–201). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Conley, D., & Glauber, R. (2006). Parental educational investment and children’s academic risk. Journal of Human Resources, 41, 722–737.

Conley, D., Pfeiffer, K., & Velez, M. (2006). Explaining sibling differences in achievement and behavioral outcomes: The importance of within- and between-family factors. Social Science Research, 56, 1087–1104.

Conley, D., Strully, K., & Bennett, N. (2006). Twin differences in birth weight: The effects of genotype and prenatal environment on neonatal and post-neonatal mortality. Economics and Human Biology, 4, 151–183.

Downey, D. B., & Pribesh, S. (2004). When race matters: Teachers’ evaluations of students’ classroom behavior. Sociology of Education, 77, 267–282.

Duryea, S., & Arends-Kuenning, M. (2003). School attendance, child labor and local labor market fluctuations in urban Brazil. World Development, 31, 1165–1178.

Farkas, G. (2003). Racial disparities and discrimination in education: What do we know, how do we know it, and what do we need to know? Teachers College Record, 105, 1119–1146.

Fleiss, J. L. (1981). The measurement of interrater agreement. In J. L. Fleiss, B. Levin, & M. C. Paik (Eds.), Statistical methods for rates and proportions (2nd ed., pp. 212–304). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Francis, A. M., & Tannuri-Pianto, M. (2012). The redistributive equity of affirmative action: Exploring the role of race, socioeconomic status, and gender in college admissions. Economics of Education Review, 31, 45–55.

Francis, A. M., & Tannuri-Pianto, M. (2013). Endogenous race in Brazil: Affirmative action and the construction of racial identity among young adults. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 61, 731–753.

Freeman, J. B., Penner, A. M., Saperstein, A., Scheutz, M., & Ambady, N. (2011). Looking the part: Social status cues shape race perception. PLoS One, 6(9), e25107. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025107

Harris, M., Consorte, J., Long, J., & Byrne, B. (1993). Who are the whites? Imposed census categories and the racial demography of Brazil. Social Forces, 72, 451–462.

Hasenbalg, C. (1979). Discriminação e desigualdades raciais no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Graal

Henriques, R. (2001). Desigualdade racial no Brasil: Evolução das condições de vida na década de 90 [Racial inequality in Brazil: Evolution of living conditions in the 1990s] (IPEA Texto para Discussão, No. 807). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada.

Hordge-Freeman, E. (2013). What's love got to do with it?: Racial features, stigma and socialization in Afro-Brazilian families. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36, 1507–1523.

Ianni, O. (1960). Segunda parte [Second part]. In F. H. Cardoso & O. Ianni (Eds.), Côr e mobilidade social em Florianópolis [Color and social mobility in Florianópolis] (pp. 153–226). São Paulo, Brazil: Companhia Editora Nacional.

Lee, J., & Bean, F. D. (2004). America’s changing color lines: Immigration, race/ethnicity, and multiracial identification. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 221–242.

Lichter, D. T., & Qian, Z. (2004). Marriage and family in a multiracial society (The American People: Census 2000 series). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation and Population Reference Bureau.

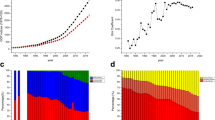

Marteleto, L. J. (2012). Educational inequality by race in Brazil, 1982–2007: Structural changes and shifts in racial classification. Demography, 49, 337–358.

Marx, A. W. (1998). Making race and nation: A comparison of the United States, South Africa, and Brazil. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McCall, L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 30, 1771–1800.

Mickelson, R. A. (2001). Subverting Swann: First- and second-generation segregation in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools. American Educational Research Journal, 38, 215–252.

Mickelson, R. A. (2003). When are racial disparities in education the result of racial discrimination? A social science perspective. Teachers College Record, 105, 1052–1086.

Mill, R., & Stein, L. C. D. (2016). Race, skin color, and economic outcomes in early twentieth-century America (Working paper). Retrieved from http://www.public.asu.edu/~lstein2/research/mill-stein-skincolor.pdf

Nobles, M. (2000). Shades of citizenship: Race and the census in modern politics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Oates, G. L. S. C. (2003). Teacher-student racial congruence, teacher perceptions, and test performance. Social Science Quarterly, 84, 508–525.

Pager, D., & Shepherd, H. (2008). The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 181–209.

Querino, A. N., de Lima, C. E., & Madsen, N. (2011). Genero, raca, e educacao no Brasil contemporaneo: Desafios para a igualdade [Gender, race, and education in contemporary Brazil: Challenges for equality]. In A. Bonetti & M. A. Abreu (Eds.), Faces da desigualdade de genero e raca no Brasil (pp. 129–149). Rio de Janiero, Brazil: Instituto de Pesquisa Economica Aplicada.

Rangel, M. A. (2015). Is parental love colorblind? Human capital accumulation within mixed families. Review of Black Political Economy, 42, 57–86.

Ribeiro, C. A. C. (2011). Desigualdade de oportunidades educacionais no Brasil: Raça, classe e gênero [Inequality in educational oportunities in Brazil: Race, class, and gender]. Educação on-Line (PUC-RJ), 8(1), 1–42.

Saperstein, A., & Penner, A. M. (2012). Racial fluidity and inequality in the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 118, 676–727.

Schwartzman, L. F. (2007). Does money whiten? Intergenerational changes in racial classification in Brazil. American Sociological Review, 72, 940–963.

Silva, N. d V. (1981). Cor e o processo de realização sócio-econômica. DADOS-Revista de Ciências Sociais, 24, 391–409.

Silva, N. d. V., & Hasenbalg, C. A. (1999). Race and educational opportunity in Brazil. In R. Reichmann (Ed.), Race in contemporary Brazil: From indifference to inequality (pp. 53–65). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Silva, P. V. B. d. (2008). Racismo em livros didáticos: Estudo sobre negros e brancos em livros de língua Portuguesa [Racism on textbooks: A study of blacks and whites in Portuguese language textbooks]. Belo Horizonte, Brazil: Autêntica Editora.

Souza, P. F. d., Ribeiro, C. A. C., & Carvalhaes, F. (2010). Desigualdade de oportunidades no Brasil: Consideracoes sobre classe, educacao e raça [Inequality in opportunities in Brazil: Considerations about class, education, and race]. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 25, 77–100.

Telles, E. E. (1995). Who are the morenas? Social Forces, 73, 1609–1612.

Telles, E. E. (2004). Race in another America: The significance of skin color in Brazil. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Telles, E. E., & Lim, N. (1998). Does it matter who answers the race question? Racial classification and income inequality in Brazil. Demography, 35, 465–474.

Telles, E. E., & Sue, C. A. (2009). Race mixture: Boundary crossing in comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 129–146.

Torche, F., & Echevarría, G. (2011). The effect of birthweight on childhood cognitive development in a middle-income country. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40, 1008–1018.

Turkheimer, E., Haley, A., Waldron, M., D’Onofrio, B., & Gottesman, I. I. (2003). Socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children. Psychological Science, 14, 623–628.

Villarreal, A. (2010). Stratification by skin color in contemporary Mexico. American Sociological Review, 75, 652–678.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Demography editor and anonymous reviewers for the helpful comments. We also thank Ed Telles for discussing the initial ideas of this article. This research was supported by Grant R24HD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Grants R24HD041025 (Population Research Institute) and T32HD007514 (Training Program), awarded to the Population Research Institute at the Pennsylvania State University by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marteleto, L.J., Dondero, M. Racial Inequality in Education in Brazil: A Twins Fixed-Effects Approach. Demography 53, 1185–1205 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0484-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0484-8