Abstract

Introduction

Recently, Italy has been heavily hit by COVID-19 pandemic and today it is still one of the most affected countries in the world. The subsequent necessary lockdown decreed by the Italian Government had an outstanding impact on the daily life of the entire population, including that of Italian surgical residents’ activity. Our survey aims to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on the training programme of Italian surgical residents.

Materials and methods

We designed a 12-item-electronic anonymous questionnaire on SurveyMonkey© web application. The survey was composed of different sections concerning demographic characteristics and impacts of COVID-19 on the concrete participation in clinical, surgical and research activities. Future perspectives of responders after the pandemic were also investigated.

Results

Eighty hundred responses were collected, and 756 questionnaires were considered eligible to be included in the study analysis. Almost 35 and 27% of respondents experienced, respectively, complete interruption of surgical and clinical activities. A subgroup analysis, comparing the COVID-19 impact on clinical activities with demographics data, showed a statistically significant difference related to specialties (p = 0.0062) and Italian regions (p < 0.0001). Moreover, 112 residents have been moved to non-surgical units dealing with COVID-19 or, in some case, they voluntarily decided to interrupt their residency programme to support the ongoing emergency.

Conclusion

Our survey demonstrated that COVID-19 pandemic has severely impacted the educational programme of Italian surgical residents. Despite many regional differences, this survey highlighted the overall shortage of planning in the re-allocation of resources facing this unexpected health emergency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On the 11th of March, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of the novel beta-COronaVIrus Disease (COVID-19) as a pandemic [1].

Currently, the spread and number of asymptomatic positive subjects is still unknown.

Medical doctors and all healthcare workers (HW) are at high risk of infection and a potential vehicle of contagion [2]. Italy has been heavily hit by the virus and today it is one of the most affected countries in the world [3]. The subsequent necessary lockdown decreed by the Italian Prime Minister had an outstanding impact on the country’s daily life.

As far as the health system is concerned, all elective surgical procedures and outpatient clinics have been stalled. Only oncological and emergency surgeries are currently guaranteed. The number of intensive care beds has been increased by 79% [4] and several hospitals have been completely dedicated to the care of COVID-19 patients.

Due to the high risk of developing medical conditions stress-related and mental health disorders, in addition to an increased physical workload, HW specialized in different surgical subdivisions had to abandon their ordinary duties to completely devote themselves to manage COVID-19 cases [5].

In Italy there is a high proportion of COVID-19 positive HW who involuntarily became disease carriers due to the long-time exposure to a large number of infected patients [6, 7].

If all HW had been provided with the appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) [8] and if a COVID-19 test would have been routinely performed, likely, such a huge number of infected HW would not have been reached [9, 10]. Furthermore, most HW do not have the required experience and background to appropriately deal with COVID-19. In fact, some surgical residents have been moved from operating rooms to the frontline operative teams against COVID-19 pandemic, while other senior residents (senior residents) had the opportunity to temporarily cover consultant positions on a voluntary basis [11].

In both cases, the new duties have been carried on without professional training on the proper use of PPE, and surgical residents have been completely subverting completely their educational programme.

Our survey aims to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on the training programme of Italian surgical residents.

Materials and methods

The Italian Polyspecialistic Society of Young Surgeon (SPIGC) designed a 12-item-electronic anonymous questionnaire on SurveyMonkey© web application (SVMK Inc., One Curiosity Way, San Mateo, United States) [12]. The purpose of this survey was explained to all participants with a brief introduction. Participants were asked to sign a privacy policy consent at the beginning. Survey participation was voluntary, and no incentives were offered. No institutional review board approval was required. This survey was registered in clinicaltrias.gov (NCT04338945).

The survey was composed of four different sections (Table 1, Supplementary File). The first section included 5 Questions (Q) concerning the level of training, and type of surgical specialty (Q1 and Q2); the Italian region in which the participant was working and the attended year of residency (Q3 and Q4); type and frequency of surgical activity routinely performed (Q5). The second section (Q6, Q7) focused on the possible impacts of COVID-19 on the active participation in clinical and surgical weekly activities, whereas the third section (Q8, Q9) on research activities during the pandemic. The last section (Q10–Q12) assessed the feeling of the impact of COVID-19 on clinical and surgical activities as well as future perspectives after the pandemic.

These questions were selected and collected by the authors, aiming to provide an accurate scenario of COVID-19 impact on residents’ activities.

The study was conducted from the 31st of March 2020 to the 6th of April 2020, and promoted with a mailing list, instant message services, and through the main Social Media Official account of the SPIGC on Facebook, Instagram, and Linked-in.

Italian surgical residents coming from any surgical specialty and attending any year of the training programme were considered eligible for the survey’s analysis. The eligibility has no relation to the residents’ curricular activities. Our sample aimed to reach approximately 5% of Italian residents in surgical specialties concerning the annual number of residency scholarship places from 2014 to 2019 and the annual drop-out percentage of residents [13]. All participants were informed that the results of the survey would have been used for further statistical evaluation and scientific publication. Anonymity was guaranteed by study design.

After the closing date for questionnaire submissions, results were downloaded as a CSV (comma-separated values) file to be analysed via Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA).

Results of the survey were reported according to the CHERRIES Guidelines [14].

Statistical analysis

All the answers collected and included in the study were processed and results were summarized as numbers (n) and percentages (%), separately for each question. The analysis of the association between questions of interest and demographics variable was also evaluated and tested by Pearson’s chi-square test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Tables and figures were used to show the results. All the analyses were performed with R software (version 3.5.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

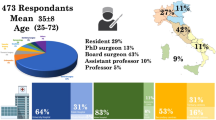

In our study 800 responses to the survey were collected. According to the selection criteria, 50 responses were excluded because they were obtained from non-residents doctors (n = 24, 3%), residents who are currently attending their training abroad (n = 9, 1.1%), and non-surgical residents (n = 17, 2.1%) (6 participants were part of two of the above-mentioned groups). Definitively, 756 questionnaires were judged eligible for study analysis. The completion rate ranged between 93.5% and 100% (Table 1, Supplementary File).

Demographic characteristics of the study population

At the time of our study, most of the respondents were attending a residency programme in general surgery (46.4%) (Table 1) being employed in the Northern regions of Italy (59.8%) (Table 2). These respondents were mainly enrolled in one of the first three years of the training course (66.3%) (Table 3).

Overall, 81.9% of the respondents used to work in elective surgical departments (such as centres dedicated to oncological and benign diseases). Only 12.5% and 2.8% of the residents were employed, respectively, in centres devoted to emergency surgery and organ transplantation (Table 3).

Impact of COVID-19 emergency on clinical and surgical weekly activities

Analysing the impact of COVID-19 on clinical activities, 112 respondents has been moved to a non-surgical unit or they have voluntarily interrupted the residence programme to support a COVID-19 emergency unit (Table 4; Fig. 1a–f); in this subgroup of residents, the majority of respondents were attending one of the first three years of the training programme in general surgery (54.5%) in the northern regions of Italy (83.0%) (Fig. 1a, b). More specifically, 20.2% of respondents were enrolled in the first year of the residency programme, 28.4% in the second year, and 22.0% in the third year (Fig. 1a).

a Graphical representation of 112 respondents who left their surgical training divided according to the attended year of residency; b graphical representation of 112 respondents who left their surgical training according to the region where they are employed; c graphical representation of 112 respondents who left their surgical training according to surgical activity; d training and research activities in the field of COVID-19 among the 112 residents who left their surgical training; e impact on clinical training programme among 112 residents who left their surgical training; f direct involvement in COVID-19 emergency activities divided according to surgical specialty among 112 residents who left their surgical training

Notably, general surgery residents were more frequently placed on non-surgical wards dedicated to the COVID-19 emergency (p = 0.0062) in comparison to the surgical residents belonging to other specialist surgeries (Fig. 2a).

a Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on residents’ active participation to clinics divided according to surgical specialty. b Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on residents’ active participation to clinics, divided according to the region where they are employed. c Impact of COVID-19 emergency on active participation to clinics divided according to the attended year of residency

Moreover, residents attending medical centres in the northern Italian regions were more commonly relocated on non-surgical wards than those belonging to central and southern Italian regions (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2b). Younger residents were more frequently transferred than older, although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.09) (Fig. 2c).

It was observed that a modification of type and timing of surgical activities occurred in the general population of residents, but without being statistically significant (Table 2, Supplementary), and consequently also in the subgroup of residents moved to COVID-19 emergency units (Table 4; Fig. 1c).

Among all the residents answering our survey, only 1% (7 respondents) had an increase of surgical activities while 3.1% (22 respondents) referred to no relevant modifications (Table 4). Most of the respondents experienced a reduction (61.3%) or a complete interruption (34.6%) of surgical activities.

Influence of COVID-19 emergency on training and research

There was an equal distribution of respondents concerning research and didactic activities (Table 4; Table 2, Supplementary). Interestingly, 16.9% of them (n = 121) declared they did not use to perform these activities even before the COVID-19 emergency.

Residents enrolled in the first year of the programme, increased research and didactic activities if compared with the IV-V year residency group (26.1 vs 22.8; p = 0.092) (Fig. 3). No other statistically significant results were found out even when comparing demographic data (Table 2, Supplementary).

Analysing data of residents moved to the COVID-19 emergency units, only 29.5% of them (n = 33) suspended didactic and research activities in the surgical field, while 19.6% of them (n = 22) increased their activities. Interestingly, the majority of them (61.6%; n = 69) took part in clinical trials dealing with COVID-19.

Relations between COVID-19 emergency and perception of future surgical training

According to 57.7% (N = 410) of the respondents, the COVID-19 emergency hurt clinical and surgical trainings as well as future career perspectives (Table 4). Moreover, 20.4% (n = 145) and 21.8% (n = 155) of the respondents reported, respectively, a positive or a not significative impact of COVID-19 emergency on their training and future ambitions (Table 4).

These data were compared with the demographic distribution. A positive impact on their clinical training was experienced especially by general surgery residents rather than those belonging to other surgical specialties (25.6% vs 15.9%; p = 0.0023) (Fig. 4a). The same result was more frequently found in the northern regions of Italy respect to central and southern Italian regions (p = 0.0027) (Fig. 4b).

Surgical training questions compared to demographic results were not statistically significant (Table 2, Supplementary).

Answers to questions regarding professional ambitions (Fig. 5a, b) showed how residents who were attending a general surgery residency programme did not substantially change their professional ambitions in comparison to residents belonging to other specialties (10.0 vs 17.2; p = 0.0217).

The residents who have been moved to the COVID-19 emergency units referred that the pandemic had a positive impact on their clinical training in 49.1% of cases, however stating a negative impact on surgical training in 87.5% of cases.

Discussion

Currently, there is no worldwide standardization of the expected technical and non-technical skills acquired during surgical training resulting in a wide variation of the operative experience among residents of different countries can be observed [15]. Moreover, surgical training directly depends on aptitude, opportunity and training method so that the standardization of a unique learning approach is even more difficult to be described [16].

This variability has been confirmed by a recent survey investigating the colorectal surgery training programme in Italy. Most of the respondents performed fewer than 10 procedures for rectal diseases during their residency. Differences were recorded among the geographical region, gender, and level of training [17]. Only 38% of the respondents received at the beginning of each year a clear programme with expected goals to be achieved, and 92% of them felt the need to increase their time in the operating room.

Italy has been the first European country strongly affected by COVID-19 spread. The geographical distribution of the participants in our study reflects the severity of the outbreak in different Italian regions, with northern Italy being the most affected area (Table 2; Fig. 1b).

COVID-19 pandemic has developed rapidly with no precedents in the last century. Consequently, there was no national coordination of the Italian residency programme with independent management based on National or Local guidelines leading to a further potential catastrophic upheaval [1]. The consequences of these differences have been widely demonstrated by our survey in which almost 35% (Table 4) and 27% (Table 4) of respondents had, respectively, complete interruption of any surgical and clinical activity. Moreover, subgroup analysis, comparing the impact on clinical activities with demographics data, confirmed this trend showing a statistically significant difference between specialties (p = 0.0062) and regions (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2a, b).

The survey reveals that 112 respondents have been moved to a non-surgical-unit or they have voluntarily interrupted their residency programme to support a non-surgical unit dealing with COVID-19 (Table 4).

Interestingly, almost 39% of this subgroup and more than half of respondents had no previous experience regarding COVID-19 pandemic (Figs. 1d, 6) with only 8.9% dedicating to research and 5.7% to training in this field. The latter is one of the reasons that led us to promote this nationwide analysis. In fact, most of the infections and deaths among HW were caused precisely by the absence of proper training and preparation as well as by the shortage of PPE.

Considering our results, we strongly disagree with this blinded and unsafe enrolment of residents and medical students to cover position in the fight against COVID-19 pandemic even though several National and International Institutions launched calls to fill temporary job postings for medical doctors and nurses, regardless of age and level of training [11, 18]. Provided that HW safety remains a priority for hospitals and patients, the risk of contagion, mainly due to asymptomatic patients [19], cannot be adequately controlled if both patients and HW are not routinely tested for coronavirus infection even in case of suspected exposure [20].

Comparing the whole sample with the 112 participants who have abandoned their trainee activity, we observed an inverted trend in the residents who had dedicated themselves to different activities with respect to their own specialties (Fig. 5a).

Interestingly, surgical residents directly involved in the COVID-19 related activities considered this situation as a good opportunity (Fig. 1e), while the majority of the other respondents were concerned about the negative impact of COVID-19 on the residency programme. These different experiences have probably led to the acquisition of additional clinical and surgical skills that may have been considered useful by the participants for a future career. However, neither the whole sample nor the 112 residents, who modified their surgical plan, believed the pandemic will play a pivotal role in their careers (Fig. 5a, b).

Our results were consistent with those of Porpiglia et al. [21] who showed how during COVID-19 emergency younger residents of urology were the most affected (Fig. 1a) and penalized due to the suspension of all elective and office-based surgical procedures. It is important to consider that residents in general surgery have been significantly more involved in COVID-19 activities than residents belonging to other specialties (Fig. 1f). These data are probably related to the lack of staff in the emergency departments with the consequent predisposition of a general surgeon with trauma care skills to be suitable compared to other physicians.

COVID-19 pandemic can be defined as a “Lesson to be learned” for all Italian surgery residency schools, which have proven to be lacking in all the aspects of the surgical training programme.

In our opinion, this could be a unique opportunity to fill the generational gap in surgery avoiding that thousands of graduated medical doctors each year are excluded from the surgical specialties for the continuous funding reductions carried out by both Italian National Health Service (Sistema Sanitario Nazionale, SSN) and the Government [22].

The study has some limitations. The heterogeneity of the respondents (level of training, specialties and geographic distribution, completion rate) could have had a certain influence on the results. Furthermore, the major limitation of our survey was the impossibility of knowing the actual number of recipients of the questionnaire in relation to those who responded. To reach the widest number of trainees possible, we used several channels to spread the survey, including several societies.

Conclusions

COVID-19 pandemic has severely impacted the educational programme of Italian surgical residents. Although with many regional differences, this survey highlighted the overall shortage of planning in the re-allocation of resources facing this unexpected epidemiologic emergency. While equally reducing the non-urgent and non-oncologic surgeries, no standard policies were adopted to employ residents’ know-hows.

Moreover, this study underlines a profound lack of both general intensive care and specific anti-COVID-19 training programmes, with a detrimental impact on the residents’ safety. Residents involved in COVID-19 treatment report an important benefit for their working future. Taking into account the possibility that future pandemics will strive again worldwide, we want to advocate the insertion of specific intensive care tasks in the curricula of surgical residency in Italy, in the context of a thorough reorganisation of the whole educational system.

References

Gallo G, Trompetto M (2020) The effects of COVID-19 on academic activities and surgical education in Italy [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 5]. J Investig Surg. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941939.2020.1748147

Rosenbaum L (2020) Facing covid-19 in Italy—ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic’s front line. N Engl J Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2005492.32187459

Giulio M, Maggioni D, Montroni I et al (2020) Being a doctor will never be the same after the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 30]. Am J Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.03.003

Wu Z, McGoogan JM (2020) Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648.32091533

Bianco F, Incollingo P, Grossi U, Gallo G (2020) Preventing transmission among operating room staff during COVID-19 pandemic: the role of the Aerosol Box and other personal protective equipment. Updates Surg 12:13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00818-2

Wu A, Huang X, Li C, Li L (2020) Novel coronavirus (2019-nCov) pneumonia in medical institutions: problems in prevention and control. Chin J Infect Control 19:1–6

Ives J, Huxtable R (2020) Surgical ethics during a pandemic: moving into the unknown? [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 30]. Br J Surg. doi:10.1002/bjs.11638

Eysenbach G (2004) Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES) [published correction appears in doi:10.2196/jmir.2042]. J Med Internet Res 6(3):e34. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34

Elsey EJ, Griffiths G, Humes DJ, West J (2017) Meta-analysis of operative experiences of general surgery trainees during training. Br J Surg 104(1):22–33

Chung RS (2005) How much time do surgical residents need to learn operative surgery? Am J Surg 190(3):351–353

Pellino G, Moggia E, Novelli E et al (2019) An update of the aims and achievements during the first year of the Young Group of the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (Y-SICCR). Tech Coloproctol 23(3):291–298

Stokes DC (2020) Senior medical students in the COVID-19 response: an opportunity to be proactive [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 25]. Acad Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13972

Graham LA, Maldonado YA, Tompkins LS, Wald SH, Chawla A, Hawn MT (2020) Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 transmission from community contacts in Healthcare Workers. Ann Surg (In press)

COVIDSurg Collaborative, (2020) Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11646

Porpiglia F, Checcucci E, Amparore D et al (2020) Slowdown of urology residents’ learning curve during COVID-19 emergency. BJU Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.15076

Colombo A, Bassani G (2019) Carenza di medici: ma per quale SSN? Dati, riflessioni e proposte dalla formazione [Lack of doctors, but for what System? Shortage of clinicians in Italy and Lombardy and reflections on structural constrains in training]. Ig Sanita Pubbl 75(5):385–402

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. SPIGC Working Group: Alessandra Aprile, Vittorio Aprile, Emanuele Botteri, Debora Brascia, Valerio Cozza, Francesco Damarco, Carlo Di Marco, Mariasole Gallazzi, Marco Giovenzana, Mario Giuffrida, Jacopo Lanari, Giovanni Lanza, Pasquale Lo Surdo, Fabio Maglitto, Mattia Manitto, Alessio Minuzzo, Nunzio Montelione, Gerardo Palmieri, Edoardo Pasqui, Federica Perelli, Elisa Piovano, Luca Portigliotti, Marta Ribolla, Angela Romano, Andrea Romboli, Giuseppe Sena, Alberto Settembrini, Alessandro Sturiale, Francesco Velluti. The authors would like to thank AISDE (Associazione Internazionale Studenti e Docenti Europei) and “Coronavirus, SARS-COV-2 e COVID-19 gruppo per soli medici” that assisted in the dissemination of the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Davide Pertile and Gaetano Gallo contributed equally to this work: Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. Drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Salomone Di Saverio and Giusi Graziano contributed equally to this work: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. Drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published. Alessandro Pasculli, Paola Batistotti, Marco Sparavigna, Giuseppe Vizzielli and Domenico Soriero contributed equally to this work: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. Fabio Barra and Eleonora Guaitoli contributed equally to this work: Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Andrea Mazzarri and Roberto Luca Meniconi contributed equally to this work: Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; Drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Davide Pertile and Gaetano Gallo shared first author position.

Members of the SPIGC Working Group are collaborators and are listed in Acknowledgements.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pertile, D., Gallo, G., Barra, F. et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on surgical residency programmes in Italy: a nationwide analysis on behalf of the Italian Polyspecialistic Young Surgeons Society (SPIGC). Updates Surg 72, 269–280 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00811-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00811-9