Abstract

In the recent years, nanotechnology has attained much attention in the every field of science. The synthesis, characterisation and applications of metallic nanoparticles (MNPs) have become an important branch of nanotechnology. In the current study, MNPs were synthesised through polyols process and applied in vitro to study their effect on medicinally important plant : Artemisia absinthium. The current study strives to check the effect of MNPs, i.e., Ag, Cu and Au on seed germination, root and shoot length, seedling vigour index (SVI) and biochemical profiling in A. absinthium. The seeds were inoculated on MS medium supplemented with various combinations of MNPs suspension. The seed germination was greatly influenced upon the application of MNPs and was recorded highest for the silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) suspensions. The best result for seed germination (98.6%) was obtained in MS medium supplemented with AgNPs as compared to control (92.9%) and other nanoparticles, i.e., copper (69.6%) and gold (56.5%), respectively, after 35 days of inoculation. Significant results were obtained for root length, shoot length and SVI in response to application of AgNPs as compared to copper nanoparticles (CuNPs) and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). These nanoparticles (NPs) could induce stress in plants by deploying the endogenous mechanism. In response to these stresses, plants produce various defence compounds. Total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) were significant in the MS medium supplemented with AgNPs as compared to other NPs, while DPPH radical scavenging assay (RSA) was highest in AuNPs treated plantlets. The MNPs showed higher toxicity level and enhanced secondary metabolites production, total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, antioxidant activity, superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and total protein content.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nanotechnology is famed as twenty-first century science and it is versatile field which covers almost all the existing branches of science. Nanotechnology has various applications in different fields like biology, physics and chemistry (Lin and Xing 2007). This science deals with the production of minute particles termed as nanoparticles. Nanoparticles have dimension between 1 and 100 nm that serve as a building block for various physical and biological systems (Sun et al. 2014). In the recent years, researchers have started the use of these nanoparticles to enhance the growth, yield, quality, production of secondary metabolites, antioxidants and disease control in plants. Studies on biological applications of various metallic nanoparticles on higher plants are increasing day by day.

Artemisia absinthium which is commonly known as ‘wormwood’ has been used as herbal medicine throughout Asia, Europe, North Africa and Middle East (Sharopov et al. 2012). This plant is a rich source of phenolics, flavonoids, terpenes and some other biologically active ingredients (Singh et al. 2012). The stem and dry leaves of A. absinthium contain 0.25–1.32% essential oils, artemisinin, anabsin, artabsin, absinthin, matricin and anabsinthin (Kordali et al. 2005). Traditionally, this plant species has been used due to trematocidal, vermifuge (Ferreira et al. 2011), bitter, insecticidal (Anderson 1977), diuretic (Mohamed et al. 2010) and against cough, common cold and diarrhoea (Hayat et al. 2009).

Plant tissue culture is considered as alternative and potential tool to conventional breeding. It improves the quality of medicinally important plants and establishes high frequency regeneration protocol. Recent advances in tissue culture techniques explained the agricultural production issues, food security and emphasised the role of biotechnological techniques for having genetically improved varieties (Oggema et al. 2007).

The secondary metabolites are significantly found in the medicinally important plants and can be exploited as reducing and capping agent and thus may act as possible agents for the nanoparticles synthesis. Elicitors are reported to effect the production of these secondary metabolites positively (Pitta-Alvarez et al. 2000). The NPs which are synthesised through polyols process have positive effect on in vitro germination parameters, i.e., germination percentage, root length, shoot length and seedling vigour index (SVI). Exogenous application of different NPs on germination has been reported by various researchers but there are still very few reports available on the in vitro application of NPs to check their effect on germination parameters. An increase in germination percentage, root length, shoot length, secondary metabolites production, total flavonoids content, total phenolic contents and total protein content in Eruca sativa L. was observed by applying various MNPs (Zaka et al. 2016). Change in growth behaviour was observed after a certain time period, so it was supposed that nanoparticles do not directly influence the plants but indirectly alters the mechanism (Navarro et al. 2008).

Entry of these nanoparticles is difficult in plants due to the presence of cell wall which may act as primary interacting site. The mechanism of the entry of these nanoparticles is still not well defined. These nanoparticles may enhance the production of hydroxyl radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which damage the cell membranes and altered the permeability. As a result of it, entry of these nanoparticles becomes easier and stress induced by these nanoparticles results in the increased production of secondary metabolites (Kim et al. 2007).

So far, few studies have been reported on the applications of nanoparticles in plant tissue culture. Khan et al. (2016) reported the seed germination and biochemical profiling of Silybum marianum exposed to different mono-metallic and bi-metallic alloy nanoparticles. So far, there is no report available on the applications of MNPs in tissue culture media to evaluate the seed germination, plant growth and secondary metabolites production in Artemisia. Hence, we evaluated the in vitro effects of chemically synthesised MNPs on growth parameters and secondary metabolites content in A. absinthium.

Materials and methods

Plant source and surface sterilisation

Seeds of A. absinthium were obtained from National Agriculture Research Council (NARC), Pakistan. Seeds were washed with running tap water followed by immersion in ethanol for 30 min. Then seeds were surface sterilised in 0.01% mercuric chloride (HgCl2) solution for 2 min followed by washing with autoclave water and dried on sterilised filter paper.

Metal nanoparticles

Metallic nanoparticles of Ag, Cu and Au were synthesised through polyols process. Reagents used were silver nitrate (AgNO3: 99%), Copper chloride (CuCl2: 98%), Hydrogen Au chloride (HAuCl4) and polyethyleneimine (2%). All these chemicals were purchased from USA.

Preparation of silver nanoparticles

For the preparation of AgNPs, 10 ml of polyethyleneimine was poured into 20 ml of 1 mM AgNO3 solution. The mixture was heated at 150 °C in oven for 15 min. The appearance of blackish colour showed the formation of AgNPs that was confirmed by UV–Visible spectroscopy.

Preparation of copper nanoparticles

For the preparation of CuNPs, 10 ml of polyethyleneimine was poured to 20 ml of 1 mM CuCl2. The solution was heated at 175 °C in oven for period of almost 30 min. The appearance of bluish black colour showed the formation of CuNPs that was confirmed by UV–Visible spectroscopy.

Preparation of gold nanoparticles

For the preparation of AuNPs, 10 ml of polyethyleneimine was poured to 20 ml of 1 mM HAuCl4. The mixture was heated at 100 °C in oven for 15 min. The appearance of yellowish black color showed the formation of AuNPs that was confirmed by UV–Visible spectroscopy.

Characterisation of metallic nanoparticles

Different techniques can be employed for the characterisation of MNPs. These nanoparticles were characterised using different characterisation techniques such as UV–Visible spectrophotometer and scanning electron microscope (SEM).

Seed germination protocol

Ag, Cu and Au nanoparticles were suspended directly in distill water using sonication for 30 min. About 30 µg/ml suspension of Ag, Cu and Au nanoparticles was added separately to MS medium in a concentration of 3/30 ml with the help of micropipette. Sterilised seeds of A. absinthium were inoculated in conical flask containing solidified MS medium. Seeds germination was observed in almost 3–5 days and first data were collected after a period of 14 days followed by data collection after every week over a period of 35 days. Overall experiment was conducted for 35 days (5 weeks).

Seed germination parameters

Percentage germination frequency

Percentage germination was recorded after every week. Seeds were taken as germinated when radicle has emerged from the seed coat (Iqbal et al. 2016).

Root and shoot length

Root and shoot length was recorded in centimetre (cm) after every week starting from the inoculation date. Mean root and shoot length was compared in form of bar chart.

Seedling vigour index (SVI)

Seedling vigour index was calculated by using the method of Abdul-Baki and Anderson (1973) and expressed as Ushahra and Malik (2013).

Analytical methods

Antioxidant activity

For antioxidant activity determination, DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) free radical scavenging assay (FRSA) was used according to the protocol described by Abbasi et al. (2010). Each dried plant tissue, approximately 10 mg, was dissolved in 4 ml of methanol and then subsequently mixed with DPPH (0.5 ml) solution. The mixture of solution was well vortexed for 15 s and then incubated for 30 min at room temperature. To conclude the final result, absorbance of sample was checked at 517 nm by using spectrophotometer. The radical scavenging assay was calculated using the following equation and expressed as percentage of DPPH discoloration.

where, A s absorbance of solution when extract was added, A b absorbance of solution when nothing added.

Total phenolic content determination

For the total phenolic content determination, Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was used according to the protocol described by Velioglu et al. (1998). About 100 µL of the plant extract was mixed with 0.75 ml Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and allowed to stand at 22 °C for 5 min. Then 0.75 ml of sodium bicarbonate solution was added to mixture and allowed to stand for 90 min at 22 °C. To conclude the final result, absorbance of sample was checked at 725 nm by using UV/Vis-DAD spectrophotometer.

Total flavonoid content determination

For the total flavonoids content determination, aluminium chloride colorimetric method was used according to the protocol described by Chang et al. (2002). About 10 mg quercetin was dissolved in 80% ethanol and then further dilutions were made. Each standard diluted solution was mixed with 1.5 ml of 95% ethanol, 0.1 ml of 10% aluminium chloride, 0.1 ml of 1 M potassium acetate and 2.8 ml of distill water and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Absorbance of the reaction mixture was checked at 415 nm by using UV/Vis-DAD spectrophotometer.

Total protein content determination

The total protein contents were determined using the method of Lowry et al. (1951) with some modifications. Enzyme extract was prepared in the same way as for antioxidant assay. The absorbance was than measured at 650 nm by using spectrophotometer. Stranded curve of BSA was then prepared by absorbance versus microgram protein or vice versa and unknown protein from the sample was determined from the curve.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

SOD activity was measured according to method of Ullah et al. (2015) with some modifications. The mixture was prepared using 130 mM methionine, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7), 0.75 mM NBT and 0.02 mM riboflavin. The mixture was exposed to fluorescent light for 7 min and the absorbance was checked at 560 nm. SOD activity was calculated sing the following Lambert–Beer law.

where A absorbance, ε extinction coefficient, L length of each wall, C concentration of enzymes.

Statistical analysis

Each treatment consisted of three replicates and each experiment was repeated twice and results were interpreted as mean standard deviation. The statistical analysis of the experimental data used Student’s t test. Each experimental value was compared with the control.

Results and discussion

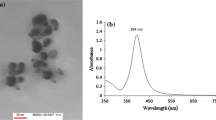

Nanoparticles can be characterised by different techniques. A combination of various techniques are usually required for the characterisation of NPs because a single technique may not fully characterise colloidal NPs. NPs synthesis was monitored by analysing through UV–Visible spectra as a function of time on HALO DB-20 spectrophotometer from the Islamic International University, Islamabad. To study the initial synthesis of NPs, the product produced by the reaction is principally analysed by UV–Vis spectroscopy. Various characterisation peaks usually in the range of 410–450 nm are obvious for the AgNPs synthesis. However, different wavelengths may attribute different shapes and sizes of colloidal AgNPs (Iravani 2011). UV–Visible spectra confirmed the formation of these MNPs. Figure 1 shows the UV–Visible spectra of AgNPs (a), CuNPs (b) and AuNPs (c). Our findings are in accordance with Rahman et al. (2012). Size of nanoparticles was determined by using Debye–Scherrer equation (Arokiyaraj et al. 2014) and has been mentioned in Table 1.

where, k is the shape factor, λ is the X-ray wavelength, θ is the Bragg’s angle, and β is the full width in radians at half maximum.

The morphology of the synthesised NPs was observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM) by using SIGMA model (MIRA3; TESCAN Brno, s.r.o., Brno, Czech Republic) from the Institute of Space and Technology (IST), Islamabad (Fig. 2).

Effect of MNPs suspension on seed germination

Germination frequency was recorded after a preliminary 2-week incubation period to 16-/8-h photoperiod. Seed germination frequency was calculated at different day intervals such as 14, 21, 28 and 35 days (Fig. 3). All seeds were grown on solidified MS medium. The effect of various MNPs suspensions on seed germination are shown in Table 2. Seeds inoculated in solidified MS medium without any suspension of MNPs were taken as control. Seed germination is extensively used in phytotoxicity test because it is simple, low cost and most suitable for unstable samples or chemicals (Munzuroglu and Geckil 2002; Wang et al. 2001). Maximum germination frequency was observed in seeds treated with AgNPs suspensions, while minimum seed germination was seen in seeds treated with AuNPs. AgNPs of different sizes, shapes and concentrations affect germination frequency differently. Small-sized NPs exert more inhibitory effects (El-Temsah and Joner 2012). With the passage of time, seed germination frequency was also increased in all the suspension of MNPs except the suspension of AuNPs. It was observed that seeds treated with AuNPs show inhibitory effects on seed germination after 28 days. Toxicity of nanoparticles depends upon both its chemical composition and release of toxic ions or stress caused by the size and shape of NPs (Brunner et al. 2006).

Root and shoot length and seedling vigour index (SVI)

It is incidental that AgNPs have positive effects as compared to CuNPs and AuNPs on root length, shoot length and SVI at different day intervals, i.e., 14, 21, 28 and 35 days with the exception in root length after 35 days, where there is significant decreased in root length was noticed. Root length, shoot length and SVI were also significantly reduced after 35 days in seeds treated with AuNPs (Table 3). These findings are in line with Savithramma et al. (2012) who reported that AgNPs penetrated and induced pores in seeds and resulted in the rapid influx of nutrients which allow the rapid growth of seeds. The precise size, shape and their chemical composition of AgNPs does matter in the responses showed by these NPs.

The copper and gold nanoparticles have reduced the root length, shoot length and SVI and exhibited more stress as compared to AgNPs in A. absinthium. Lee et al. (2008) also affirmed our findings who reported the similar results. After 35 days, the root and shoot length was reduced in MNPs as compared to the control which can be acceptable by the reason that with the passage of time more ions were released from the particles and accumulated in plantlets and they were more venomous.

Antioxidant activity

The DPPH radical scavenging activity of the MNPs treated plantlets is shown in Fig. 4. In 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay, MNPs suspension significantly affected the radical scavenging activity in Artemisia absinthium. It was found that highest DPPH activity (29.21%) was observed in plantlets treated with AuNPs as compared to other MNPs and control. AgNPs have reduced the antioxidant activity as compared to the other MNPs and control. Comparable results were obtained by other researchers in an attempt to find the effect of mono-metallic NPs and bi-metallic alloy NPs (Zaka et al. 2016; Khan et al. 2016).

Total phenolic content (TPC) and Total flavonoid content (TFC)

As shown in Fig. 5, total phenolic content is comparatively lesser in plantlets treated with AgNPs and in copper and gold treated plantlets, total phenolic content is comparable with the control. However, CuNP-treated plantlets produce considerably higher TPC. Our findings are not in agreement with Krishnaraj et al. (2012) who reported that AgNPs produce considerably higher TPC. Similarly, total flavonoid content is comparatively higher in plantlets treated with CuNPs as compared to Ag and Au nanoparticles treated plantlets. So we can conclude that CuNPs are responsible for inducing more stress as compared to AgNPs and AuNPs. Our observations are in line with Zaka et al. (2016) who reported similar findings in an attempt to check the effect of MNPs for TPC and TFC in Eruca sativa.

Total protein content and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

In this study, effect of MNPs on the total protein content and superoxide dismutase activity was also evaluated. The total protein content and SOD activity of the MNPs treated plantlets are shown in Fig. 6. As shown in Fig. 6, the total protein content is comparatively less in the plantlets treated with CuNPs as compared to the control and other MNPs. High total protein contents also correlate with higher SOD activity. The main factor which is involved in the higher total protein content and SOD activity could be the stress. SOD and total protein content were hampered by the Cu ions presence in the medium (Nekrasovaa et al. 2011).

Conclusion

It is concluded that MNPs showed different behaviours than metals in bulk form. Size, shape and chemical composition of the MNPs significantly influence the plants. All these factor influence singly or in combination to enhance or in some cases inhibit the germination and growth. It is confirmed from the present study that small-sized NPs are more toxic than large-sized NPs. Among the MNPs used, CuNPs are more stress inducing as compared to AuNPs and AgNPs. The reason behind that copper at bulk level is also more toxic than silver and gold. TPC and TFC were highest (6.8 and 0.9 µg/mg DW) with the application of CuNPs as compared to AgNPs and AuNPs. SOD activity was significant (0.34 nM/min/mg FW) with the application of AuNPs as compared to AgNPs and CuNPs. Once the nanoparticles enter into seeds, then it has long-lasting effects on the germination, growth and biochemical profiling. So far, there are very few reports available of nanomaterials regarding the stress inducing factors in plant tissue culture. These preliminary findings warrant more comprehensive study about the ecotoxicity of the MNPs in future.

References

Abbasi BH, Khan MA, Mahmood T, Ahmad M, Chaudhary MF, Khan MA (2010) Shoot regeneration and free radical scavenging activity in Silybum marianum L. Plant Cell Tiss Org Cult 101:371–376

Abdul-Baki AA, Anderson JD (1973) Vigor determination in soybean and seed multiple criteria. Crop Sci 13:630–633

Anderson FJ (1977) An illustrated history of the herbals. Columbia University Press, New York

Arokiyaraj S, Arasu MV, Vincent S et al (2014) Rapid green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Chrysanthemum indicum L. and its antibacterial and cytotoxic effects: an in vitro study. Int J Nanomed 9:379–388

Brunner TJ, Wick P, Manser P (2006) In vitro cytotoxicity of oxide nanoparticles: comparison to asbestos, silica, and the effect of particle solubility. Environ Sci Technol 40:4374–4381

Chang C, Yang MH, Wen HM, Chern J (2002) Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complimentary colorimetric method. J Food Drug anal 10:178–182

El-Temsah YS, Joner EJ (2012) Impact of Fe and Ag nanoparticles on seed germination and differences in bioavailability during exposure in aqueous suspension and soil. Environ Toxicol 27:42–49

Ferreira FS, Jorge P, Peaden J, Keiser J (2011) In vitro trematocidal effects of crude alcoholic extracts of Artemisia annua, A. absinthium, Asiminatriloba, and Fumaria officinalis. Parasitol Res 109:1585–1592

Hayat MQ, Khan MA, Ashraf M, Jabeen S (2009) Ethnobotany of the genus Artemisia L. (Asteraceae) in Pakistan. Ethnobot Res Appl 7:147–162

Iqbal M, Asif S, Ilyas N, Raja NI, Hussain M, Shabir S, Faz MNA, Rauf A (2016) Effect of plant derived smoke on germination and post germination expression of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Am J Plant Sci 7:806–813

Iravani S (2011) Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Green Chem 13:2638–2650

Khan MS, Zaka M, Abbasi BH, Rahman L, Shah A (2016) Seed germination and biochemical profile of Silybum marianum exposed to monometallic and bimetallic alloy nanoparticles. IET Nanobiotech 10(6):1–8

Kim JS, Kuk E, Yu KN (2007) Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 3:95–101

Kordali S, Cakir A, Mavi A, Kilic H, Yildirim A (2005) Screening of chemical composition and antifungal and antioxidant activities of the essential oils from three Turkish Artemisia species. J Agric Food Chem 53:1408–1416

Krishnaraj C, Jagan EG, Ramachandran R (2012) Effect of biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles on Bacopa monnieri (Linn.) Wettst Plant growth metabolism. Process Biochem 47:651–658

Lee W, An Y, Yoon H (2008) Toxicity and bioavailability of copper nanoparticles to the terrestrial plants mung bean (Phaseolusradiatus) and wheat (Triticum aestivum): plant uptake for water insoluble nanoparticles. Environ Toxicol Chem 27:1915–1921

Lin D, Xing B (2007) Phytotoxicity of nanoparticles: inhibition of seed germination and root growth. Environ Pollut 150:243–250

Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AI, Randall RJ (1951) Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Bio Biochem 193(1):265–275

Mohamed AH, El-Sayed MA, Hegazy ME, Helaly SE, Esmail AM, Mohamed NS (2010) Chemical constituents and biological activities of Artemisia herbaalba. Rec Nat Prod 4:1–2

Munzuroglu O, Geckil H (2002) Effects of metals on seed germination, root elongation, and coleoptile and hypocotyl growth in Triticum aestivum and Cucumis sativus. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 43:203–213

Navarro E, Piccapietra F, Wagner B (2008) Toxicity of silver nanoparticles to Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Environ Sci Technol 42:8959–8964

Nekrasovaa GF, Ushakova OS, Ermakov AE (2011) Effects of copper (II) ions and copper oxide nanoparticles on elodea densa planch. Russ J Ecol 42:458–463

Oggema JN, Kinyua MG, Ouma JP, Owuoche JO (2007) Agronomic performance of locally adapted sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) cultivars derived from tissue culture regenerated plants. Af J Biotech 6(12):1418–1425

Pitta-Alvarez SI, Spollansky TC, Giulietti AM (2000) The influence of different biotic and abiotic elicitors on the production and profile of tropane alkaloids in hairy root cultures of Brugmansia candida. Enzyme Microb Technol 26:491–504

Rahman LU, Qureshi R, Yasinzai MM, Shah A (2012) Synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of Ag–Cu alloy nanoparticles prepared in various ratios. Comptes Rendus Chim 15:533–538

Savithramma N, Ankanna S, Bhumi G (2012) Effect of nanoparticles on seed germination and seedling growth of Boswellia ovalifoliolata—an endemic and endangered medicinal tree taxon. Nano Vis 2:61–68

Sharopov FS, Sulaimonova VA, Setzer WN (2012) Composition of the essentialoil of Artemisia absinthium from Tajikistan. Rec Nat Prod 6(2):127–134

Singh R, Verma PK, Singh G (2012) Total phenolic, flavonoids and tannin contents in different extracts of Artemisia absinthium. J Intercult Ethnopharmacol 1(2):101–104

Sun T, ZhangYS Pang B, Hyun DC, Yang M, Xia Y (2014) Engineered nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed 53:12320–12364

Ullah N, Haq IU, Safdar N (2015) Physiological and biochemical mechanisms of allelopathy mediated by the allelochemical extracts of Phytolacca latbenia (Moq.) H. Walter. Toxicol Ind Health 31:931–937

Ushahra J, Malik CP (2013) Putrescine and ascorbic acid mediated enhancement in growth and antioxidant status of Eruca sativa varieties. CIB Tech J Biotechnol 2:53–64

Velioglu YS, Mazza G, Gao L, Oomach BD (1998) Antioxidant activity and total phenolics in selected fruits, vegetables and grains products. J Agri Food Chem 46:4113–4117

Wang X, Sun C, Gao S (2001) Validation of germination rate and root elongation as an indicator to assess phytotoxicity with Cucumis sativus. Chemosphere 44:1711–1721

Zaka M, Abbasi BH, Rahman L, Shah A, Zia M (2016) Synthesis and characterisation of metal nanoparticles and their effects on seed germination and seedling growth in commercially important Eruca sativa. IET Nanobiotech 10(3):1–7

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hussain, M., Raja, N.I., Mashwani, ZUR. et al. In vitro seed germination and biochemical profiling of Artemisia absinthium exposed to various metallic nanoparticles. 3 Biotech 7, 101 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0741-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-017-0741-6