Abstract

Drought stress due to water deficit is a major problem of rice cultivation as a most drought-sensitive crop plant. A rice mutant line (MT58) was developed after mutagenesis of cv. Neda by ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) and selected for dwarfism (18 cm shorter than Neda). The extent of its molecular changes relative to parental cultivar was assessed by SSR and ISSR markers, and the response of the line along with parental cultivar and another mutant line (MTA) to mild and severe water deficit, was evaluated in a field experiment. A molecular assessment using 41 SSR markers showed that dwarf line MT58 had significant molecular difference with two other lines. ISSR assay also proved the considerable mutational effect of EMS on two mutant lines compared with the original wild line. Field experiments revealed that limited irrigation caused mild-to-severe decrease in all the studied traits, including chlorophyll contents. In mild water-stress mutant line, MT58 showed a low (3 %) yield loss as compared with cultivar Neda with a high (14 %) yield loss. Interestingly, in severe water-stress mutant line, MT58 showed a low (19 %) yield loss as compared with mutant line MTA and cv. Neda with high (33 and 31 %, respectively) yield loss. In severe stress, mutant MT58 had the highest values of panicle length, total kernels per panicle, fertile kernels, and chlorophyll contents, while cv. Neda had the highest values of plant height, tiller number, and plant yield, and reduction in chlorophyll content at drought stress condition was correlated with yield loss (0.64 and 0.697 for chl.a and chl.b, respectively). The results of this research obviously confirm that mutant line MT58 despite of its stunt figure shows a low yield loss due to drought stress and hence is a promising line for cultivation under drought condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Abiotic stresses especially drought can affect the physiological status of an organism and have adverse effects on growth, development, and metabolism (Chutia and Borah 2012). Drought is an abiotic stress which affects plants at various levels and stages of their life period. This abiotic stress not only affects plant–water relations through the reduction of water content, turgor, and total water, but it also affects stomatal closure, limits gas exchange, reduces transpiration, and disturbs photosynthesis (Razak et al. 2013). Negative effects of water deficit on mineral nutrition and metabolism decrease the leaf area and alter assimilate partitioning among the plant organs (Zain et al. 2014).

Drought stress is of high importance, particularly for drought-sensitive plants, such as rice. Rice varieties have differential responses to abiotic stresses because of the complexity of interactions between stress factors and various molecular, biochemical, and physiological processes that affect plant growth and development (Zhu 2002; Wadhwa et al. 2010). Drought stress due to water deficit is a common constraint in upland cultivation systems of plants (Zain et al. 2014). More than the 20 million hectares of rain-fed lowland rice worldwide suffer water deficit at different growth stages (Cabangon et al. 2002; Quampah et al. 2011; Zain et al. 2014). Drought stress reduces the rice growth and severely affects different traits, such as seedling biomass, stomatal conductance, photosynthesis, starch metabolism, and plant–water relations (Sarkarung et al. 1997; Jaleel et al. 2009; Farooq et al. 2009; Quampah et al. 2011). Pantuwan et al. (2000) reported that grain yield of some rice varieties was reduced by up to 81 % under drought condition and this reduction depended on timing, duration, and severity of the plant water stress. Cha-um et al. (2010) reported differential responses of rice genotypes to water deficit. They observed when rice genotyped exposed to water deficit, panicle length and fertile grains in two tolerant varieties were not significantly decreased, leading to greater productivity than in two sensitive cultivars (Cha-um et al. 2010).

Influence of the environmental stresses on growth and yield can be estimated by measurement of photosynthetic traits, such as chlorophyll content and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, since these traits have a close correlation with carbon exchange rate (Guo and Li 2000). Energetic status of the chloroplast increases as a consequence of the water stress which has a direct relationship to that of increased amount of total chlorophyll and Chla and Chlb among the stressed induced verities (Ranjbarfordoei et al. 2000). Rice is one of the most drought-susceptible crops, especially at the reproductive stage (Agarwal et al. 2016). It was reported that at rain-fed conditions, water deficit has a serious effect, especially at the booting stage, during which plants are particularly drought-susceptible, leading to low-crop productivity (Pantuwan et al. 2002).

Since water availability will be a major constraint for paddy rice productivity in the near future, we studied the response of a dwarf mutant line of rice (recently developed in our research group using mutagenesis by ethyl methane sulfonate, EMS) along with its parental cultivar to water deficit aiming to evaluate effect of dwarfism on morpho-physiological traits, particularly plant yield in a field experiment.

Materials and methods

Plant material

An elite high-yielding rice cultivar, Neda (widely cultivated at North of Iran), was mutagenized using ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) and a mutant line with dwarfism was selected from M2 population (Shojaeian 2011). In addition, another mutant line with improved yield was included in the study. Original cv. Neda along with these two promising mutant lines (MT58 and MTA) was evaluated under drought stress.

Drought induction and morpho-physiological measurements

Field experiment was conducted in research farm of Gorgan University of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources in 2013 in a split block design with three replications. Three genotypes [Neda, MT58 (M5), and MTA (M5)] were sown in three blocks of irrigation (S0: full irrigation; S1: 1 day irrigation followed by 1 day no irrigation; S2: 1 day irrigation followed by 2 days no irrigation). Plants of each genotype were transplanted in plots of five rows with 25 cm between rows and 25 cm spacing between hills. A single 30-day-old seedling was transplanted per hill. At appropriate times, some important traits were evaluated, including morphological traits [plant height (PLH), panicle length (PL), total kernels per panicle (TK), fertile kernels (FK) per panicle, tiller number (TN), 100-kernel weight (HKW), and plant yield (PY)] and physiological characters [chlorophyll a (Chl.a), chlorophyll b (Chl.b), and total chlorophyll (Chl.a + b) contents]. Chlorophyll contents were determined by taking fresh leaf samples (0.1 g) from flag leaves three times in reproductive phase (start of panicle emergence, 1 day after panicle emergence and 2 days after panicle emergence). The samples were homogenized with 5 mL of acetone (80 % v/v) using pestle and mortar and centrifuged at 5000 rpm. The absorbance was measured with a UV/visible spectrophotometer at 663.6 and 646.6 nm, and chlorophyll contents were calculated using the equations proposed by Porra (2002).

Molecular assessments

Cultivar Neda along with two promising mutant lines (MT58 with stunt figure and MTA) was evaluated at molecular level using 41 simple sequence repeat (SSR) primer pairs (http://www.gramene.org; RM522, RM7300, RM6128, RM272, RM134, RM3510, RM5373, RM311, RM1146, RM3233, RM1, RM7180, RM7241, RM207, RM131, RM25, RM215, RM158, RM417, RM320, RM516, RM502, RM332, RM317, RM339, RM457, RM687, RM50, RM206, RM242, RM527, RM566, RM3873, RM283, RM505, RM481, RM106, RM159, RM171, RM412, and RM1108). The primer sequences, genomic locations, and other useful information are presented in Supplementary file S1. In addition, ten inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) primers were used for genotyping of the studied lines (Table 1). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mixture was prepared in a 0.2-mL tubes and each single reaction included 5 µL of deionized water, 6-µL PCR Master Mix (CinaClone Co.), 0.25 µL of each primer (10 pg), and 0.75 µL of DNA template (15 ng). In the case of SSR assays, the PCR amplification started at 94 °C for 4 min and continued for 35 cycles, including denaturation at 94 °C for 35 s, annealing at 55 °C for 35 s, and extension at 72 °C for 40 s. The synthesis was completed at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 3.5 % agarose gel and 1ξ TBE buffer containing 0.5 µg mL−1 ethidium bromide. In the case of ISSR assays, the PCR amplification started at 94 °C for 4 min and continued for 35 cycles, including denaturation at 94 °C for 35 s, annealing at 47 °C for 35 s, and extension at 72 °C for 2 min. The synthesis was completed at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 1.5 % agarose gel and 1ξ TBE buffer containing 0.5-µg mL−1 ethidium bromide. Electrophoresis gels were photographed under ultraviolet light by a Gel-Doc system (BioRad, USA).

Data analysis

Morphological field data were analyzed using the SAS software (version 9.3) (SAS Institute 2009). Mean comparisons were performed using Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05). SSR and ISSR score data were analyzed using NTSYSpc (version 2.2). A cluster analysis based on marker data was done in NTSYSpc (version 2.2).

Results

SSR and ISSR assays

At all SSR loci, wild-type line Neda, and mutant line MTA showed identical banding patterns. However, mutant line MT58 showed different banding patterns in 7 out of 41 SSR loci, including RM1, RM3510, RM3233, RM1146, RM206, RM3873, and RM505. Most of these polymorphic SSRs have dinucleotide AG or GA repeated motifs; the exceptions are RM505 and RM3510 with dinucleotide CT repeat (for more details, see supplementary file S1) Cluster analysis placed the mutant line MT58 in a separate group and two lines Neda and MTA in another group with >90 % bootstrap support (Fig. 1 top); in addition, the grouping was validated by a high cophenetic correlation coefficient (r = 0.968). However, based on ISSR markers, of 54 produced bands by 10 ISSR primers, 26 polymorphic bands (48.1 %) were observed between three genotypes. Cluster analysis differentiated the two mutant lines from wild-type line Neda and they were placed in a separate group with a high bootstrap support (Fig. 1 bottom); in this case, also the grouping was validated by a high cophenetic correlation coefficient (r = 0.962).

Effect of water deficit on morphological traits

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that water stress significantly affected morphological traits, including plant height (PLH) and plant yield (PY) (Table 2), indicating that these traits were highly affected by irrigation regime. Genotype effect was significant for all morphological traits except for tiller number and plant yield. Effect of stress × genotype interaction was significant only for plant height.

Mean’s comparisons revealed that irrigation regimes had significant differences in all the studied traits except for 100-kernel weight (Table 3). As expected, maximum performance of all traits was observed in normal irrigation (S0). Mild water stress (S1) and severe water stress (S2), respectively, had moderate and severe negative effects on all the studied traits. Particularly, severe water deficit (S2) compared with normal irrigation significantly decreased plant height (8 cm), total kernels per panicle (18 kernels), tiller number (2 tillers), and plant yield (12 g/plant).

Mean’s comparisons for different genotypes showed that the three studied genotypes showed identical performance for tiller number and plant yield. Elite cultivar Neda along with mutant line MTA had higher performance for plant height and 100-kernel weight, while mutant line MT58 had higher performance for panicle length, total kernels per panicle, and fertile kernels, and showed significant dwarfism (~18 cm) relative to two other genotypes (Table 3).

Further analysis on the stress × genotype interactions showed that in normal irrigation (S0), cultivar Neda had highest plant height, tiller number, and plant yield (Fig. 2; Table 4), while mutant line MTA had highest 100-kernel weight. Stunt mutant line MT58 in normal irrigation had highest panicle length, total kernels per panicle, and fertile kernels, and had shortest plant height. In severe water deficit (S2), all genotypes showed similar trend to what observed in mild water stress in most studied traits.

Response of studied genotypes to water deficit. Left plant height, right plant yield, S 0 normal irrigation, S 1 1 day irrigation followed by 1 day no irrigation, S 2 1 day irrigation followed by 2 days no irrigation. Columns with common letters have not significant differences at 5 % level of probability

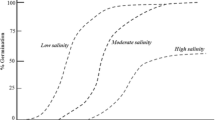

Assessment of yield loss due to water deficit revealed that in mild water stress (S1), cultivar Neda and mutant line MT58 showed highest (14 %) and lowest (3 %) yield loss, respectively (Fig. 3), while in severe water-deficit mutant lines, MTA and MT58 showed highest (33 %) and lowest (19 %) yield loss, respectively. Neda also showed relatively high yield loss (31 %).

Effect of water deficit on chlorophyll contents

In the case of chlorophyll contents, ANOVA showed that water stress significantly affected Chl.a and Chl.b at all panicle emergence stages T1–T3 (Table 5). Genotype effect was also significant for these physiological traits, while the effect of stress × genotype interaction was significant for Chl.a at all panicle emergence stages and for chl.b at emergence stage T1 (Table 5).

Water deficit considerably affected chlorophyll contents. Chl.a and Chl.b contents were reduced under both mild and severe drought stress (Table 6). Dwarf mutant line MT58 had higher chl.a contents than that of two other genotypes at all panicle emergence stages. The line also had higher chl.b contents at panicle emergence stages T1 and T2, but had not any difference from mutant line MTA at T3 stage. The analysis of stress by genotype interaction showed that at normal irrigation condition (S0), all genotypes did not differ in chlorophyll contents (as representative, Fig. 4 relates to T1 stage of panicle emergence), while at mild stress condition (S1), two mutant lines accumulated more Chl.b relative to elite cultivar Neda, and mutant line MT58 had higher Chl.a than two other genotypes. At severe stress condition (S2), mutant line MT58 accumulated more chlorophylls, although its Chl.a was significantly higher than that of two other genotypes.

Correlation analysis showed that among morphological traits, panicle length (PL) had highest (0.862) significant correlation with plant yield, followed by fertile kernels (FK) per panicle (0.455), and tiller number (TN) (0.45), and all chlorophyll contents had a high significant positive correlation (>0.64) with plant yield (Table 7).

Discussion

In this research, we analyzed the molecular differences of an original line (Neda) and two mutant lines developed after mutagenesis of Neda line using EMS chemical mutagen. As shown, the mutation did not affect most studied SSR loci, so only 7 out of 41 loci (17.1 %) governed mutational changes in one of mutant lines (MT58). Wu et al. (2005) found no mutational changes between original rice line IR64 and nearly all morphological mutants using 12 SSR markers. In contrast, Poli et al. (2013) reported polymorphism in 6 SSR loci between IR64 and its isogenic-mutant line Nagina22. These results indicate that EMS could induce an adequate number of mutated loci in mutant MT58. In another study on wheat, Zhang et al. (2015) reported that near 21 % of SSR markers showed polymorphism between original line and an EMS-induced mutant.

In our research, in another hand, ISSR assay showed that 26 out of 54 loci (48.1 %) governed mutational changes between three studied genotypes. Wannajindaporn et al. (2014) in a research on Dendrobium reported a 22.5 % polymorphism in ISSR loci between original clone (Earsakul) and 28 of its mutant clones. In a work by Ahmadikhah et al. (2014) to study the EMS-induced salt tolerance in rice, 50 % of ISSR markers showed polymorphism between wild cultivar and nine mutant lines.

In water-stress assays, we found that water deficit as expected negatively imposed all evaluated morpho-physiological characters of rice plant, but the severity of loosed performance differed depending on stress level and genotype. In both mild and severe water-stresses mutant dwarf line MT58 showed lowest (3 and 19 %, respectively) yield loss. Grain yield under stress environment is the primary trait for the improvement of drought tolerance. Drought effect on seed yield is due to the relation with duration of watering from flowering until physiological maturity (Midaoui et al. 2003).

Photosynthesis is an essential process to maintain crop growth and development, and it is well known that photosynthetic systems in higher plants are most sensitive to drought stress (Falk et al. 1996). Chlorophyll is one of the major chloroplast components for photosynthesis, and relative chlorophyll content has a positive relationship with photosynthetic rate (Guo and Li 2000). Dalal and Tripathy (2012) showed that chlorophyll content was reduced under PEG-induced drought stress in rice seedlings. Ganji Arjenaki et al. (2012) also observed a reduction in chlorophyll content due to water stress at anthesis stage in wheat. Exposure to drought stress leads to a significant effect in Chlorophyll.a and Chlorophyll.b contents (Ranjbarfordoei et al. 2000). In our study, also chlorophyll contents showed considerable sensitivity to water deficit, so that with a mild water stress, all chlorophyll contents were reduced compared with normal water condition, and in a more severe water stress, their reduction was more visible (Table 3). Genotype reaction to water deficit was well observable in their chlorophyll accumulation at drought stress condition; this issue can be particularly observed for chl.a content (Table 3). Cha-um et al. (2010) and Mafakheri et al. (2010) reported a marked decrease in all physiological parameters due to drought stress in drought-sensitive rice and chickpea genotypes, respectively. A reason for decrease in chlorophyll content as affected by water deficit is that drought stress by producing reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as O2 − and H2O2, can lead to lipid peroxidation and, consequently, chlorophyll destruction (Mirnoff 1993; Foyer et al. 1994; Hirt and Shinozaki 2004). In addition, with decreasing chlorophyll content due to the changing green color of the leaf into yellow, the reflectance of the incident radiation is increased (Schlemmer et al. 2005).

Correlation analysis showed a clear positive relationship (>0.64) between plant yield and chlorophyll contents (Table 4), probably due to maintaining stay-green state despite of water deficit, especially in two less sensitive mutant lines, MTA and MT58. Although there is an argument about whether a higher chlorophyll content (i.e., stay-green trait) contributes to yield under drought conditions or not (Blum 1998), many studies indicated that stay-green is associated with improved yield and transpiration efficiency under water-limited conditions in sorghum, maize, wheat, barley, and rice (Benbella and Paulsen 1998; Borrell et al. 2000; Haussmann et al. 2002; Verma et al. 2004; Li et al. 2006; Cha-um et al. 2010).

Conclusion

Based on molecular studies in this research, it can be concluded that EMS did not alter most studied SSR loci, while it introduced adequate mutational alterations in ISSR regions. Field experiments revealed that water deficit negatively affects all evaluated morpho-physiological characters of rice plant and that maintaining yield under water stress mainly is possible via continuing photosynthesis activity and staying green the leaves. With regard to all aspects of findings of our research, mutant line MT58 despite of its stunt figure did not show yield difference from its parental cultivar under drought stress.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- EMS:

-

Ethyl methane sulfonate

- FK:

-

Fertile kernels

- HKW:

-

100-Kernel weight

- ISSR:

-

Inter simple sequence repeat

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PL:

-

Panicle length

- PLH:

-

Plant height

- PY:

-

Plant yield

- SSR:

-

Simple sequence repeat

- TK:

-

Total kernels per panicle

- TN:

-

Tiller number

References

Agarwal P, Parida SK, Raghuvanshi S, Kapoor S, Khurana P, Khurana JP, Tyagi AK (2016) Rice Improvement Through Genome-Based Functional Analysis and Molecular Breeding in India. Rice 9:1

Ahmadikhah A, Shojaeian H, Pahlevani M, Nayyeripasand L (2014) Identification of salt tolerant mutants in rice and their fingerprinting using ISSR markers. Mod Genet 9(3):299–312

Benbella M, Paulsen GM (1998) Efficacy of treatments for delaying senescence of wheat leaves: 11. Senescence and grain yield under field conditions. Agron J 90:332–338

Blum A (1998) Improving wheat grain filling under stress by stem reserve mobilization. Euphytica 100:77–83

Borrell AK, Hammer GL, Henzell RG (2000) Does maintaining green leaf area in sorghum improve yield under drought? 11. Dry matter production and yield. Crop Sci 40:1037–1048

Cabangon RJ, Tuong TP, Abdullah NB (2002) Comparing water input and water productivity of transplanted and direct-seeded rice production systems. Agric Water Manag 57:11–31

Cha-um S, Yooyongwech S, Supaibulwatana K (2010) Water deficit stress in the reproductive stage of four indica rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes. Pak J Bot 42(5):3387–3398

Chutia J, Borah SP (2012) Water stress effects on leaf growth and chlorophyll content but not the grain yield in traditional rice (Oryza sativa Linn.) genotypes of Assam, India II. Protein and proline status in seedlings under PEG induced water stress. Am J Plant Sci 3:971–980

Dalal VK, Tripathy BC (2012) Modulation of chlorophyll biosynthesis by water stress in rice seedlings during chloroplast biogenesis. Plant Cell Environ 35:1685–1703

Falk S, Maxwell DP, Laudenbach DE, Huner NPA, Baker NR (1996) Photosynthesis and the Environment. In: Advances in photosynthesis, vol 5. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 367–385

Farooq H, Basra SMA, Wahid H, Rehman H (2009) Exogenously applied nitric oxide enhances the drought tolerance in fine grain aromatic rice (Oryza sativa L.). J Agron Crop Sci 195(4):254–261

Foyer CH, Descourvieres P, Kunert KJ (1994) Photo oxidative stress in plants. Plant Physiol 92:696–717

Ganji Arjenaki F, Jabbari R, Morshedi A (2012) Evaluation of drought stress on relative water content, chlorophyll content and mineral elements of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties. Int J Agric Crop Sci 4(11):726–729

Guo P, Li R (2000) Effects of high nocturnal temperature on photosynthetic organization in rice leaves. Acta Botanica Sinica 42:13–18

Haussmann BIG, Mahalakshmi V, Reddy BVS, Seetharama N, Hash CT, Geiger HH (2002) QTL mapping of stay-green in two sorghum recombinant inbred populations. Theor Appl Genet 106:133–142

Hirt H, Shinozaki K (2004) Plant responses to abiotic stress. Springer, Berlin

Jaleel CA, Manivannan PA, Wahid A, Farooq M, Al-Juburi HJ, Somasundaram RA, Panneerselvam R (2009) Drought stress in plants: a review on morphological characteristics and pigments composition. Int J Agric Biol 11(1):100-105

Li RH, Gou PP, Baum M, Grand S, Ceccarelli S (2006) Evaluation of chlorophyll content and fluorescence parameters as indicators of drought tolerance in barley. Agric Sci China 5(10):751–757

Mafakheri A, Siosemardeh A, Bahramnejad B, Struik PC, Sohrabi Y (2010) Effect of drought stress on yield, proline and chlorophyll contents in three chickpea cultivars. Aust J Crop Sci 4(8):580–585

Midaoui ME, Serieys H, Kaan F (2003) Effects of osmotic and water stresses on root and shoot morphology and seed yield in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) genotypes breed for Morocco or issued from introgression with H. argophyllus T. & G. and H. debilis Nutt. Hellia 26(38):1–16

Mirnoff N (1993) The role of active oxygen in the response of plants to water deficit and desiccation. New Phytol 125:27–58

Pantuwan G, Fukai S, Cooper M, Rajatasereekul S, O’Toole JC (2000) Field screening for drought resistance. In: Increased lowland rice production in the Mekong region. Proceedings of International Workshop (Vientiane, Laos), pp 69–77

Pantuwan G, Fukai S, Cooper M, Rajatasereekul S, O’Toole JC (2002) Yield response of rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes to drought under rainfed lowlands. 2. Selection of drought resistant genotypes. Field Crops Res 73:169–180

Poli Y, Basava RK, Panigrahy M, Vinukonda VP, Dokula NR, Voleti SR, Neelamraju S (2013) Characterization of a Nagina22 rice mutant for heat tolerance and mapping of yield traits. Rice 6(1):36

Porra RJ (2002) The chequered history of the development and use of simultaneous equations for the accurate determination of chlorophylls a and b. Photosynth Res 73:149–156

Quampah A, Wang RM, Shamsi IH, Jilani G, Zhang Q, Hua S, Xu H (2011) Improving water productivity by potassium application in various rice genotypes. Int J Agric Biol 13:9–17

Ranjbarfordoei A, Samson R, Damne PV, Lemeur R (2000) Effects of drought stress induced by polyethylene glycol on pigment content and photosynthetic gas exchange of Pistacia khinjuk and P. mutica. Photosynthetica 38(3):443–447

Razak AA, Ismail MR, Karim MF, Wahab PEM, Abdullah SN, Kausar H (2013) Changes in leaf gas exchange, biochemical properties, growth and yield of chilli grown under soilless culture subjected to deficit fertigation. Aust J Crop Sci 7:1582–1589

Sarkarung S, Pantuwan G, Pushpavesa S, Tanupan P (1997) Germplasm development for rainfed lowland ecosystems: breeding strategies for rice in drought-prone environments. In: Proceedings of International Workshop (UbonRatchathani, Thailand), pp 43–49

SAS Institute (2009) SAS proprietary software. Version 9.3. SAS Inst., Cary

Schlemmer MR, Francis DD, Shanahan JF, Schepers JS (2005) Remotely measuring chlorophyll content in corn leaves with differing nitrogen levels and relative water content. Agron J 97:106–112

Shojaeian H (2011) Evaluation of phenotypic and molecular diversity induced by mutagen of ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) in rice. M.Sc. Thesis. Gorgan University of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, Gorgan, Iran

Verma V, Foullces MJ, Worland AJ, Sylvester-Bradley R, Caligari PDS, Snape JW (2004) Mapping quantitative trait loci for flag leaf senescence as a yield determinant in winter wheat under optimal and drought-stressed environments. Euphytica 135:255–263

Wadhwa R, Kumari N, Sharma V (2010) Varying light regimes in naturally growing Jatropha curcus: pigment, proline and photosynthetic performance. J Stress Physiol Biochem 6(4):67–80

Wannajindaporn A, Poolsawat O, Chaowiset W, Tantasawat PA (2014) Evaluation of genetic variability in in vitro sodium azide-induced Dendrobium ‘Earsakul’mutants. Genet Mol Res 13(3):5333

Wu JL, Wu C, Lei C, Baraoidan M, Bordeos A, Madamba MRS, Bruskiewich R (2005) Chemical-and irradiation-induced mutants of indica rice IR64 for forward and reverse genetics. Plant Mol Biol 59(1):85–97

Zain NAM, Ismail MR, Mahmood M, Puteh A, Ibrahim MH (2014) Alleviation of water stress effects on MR220 rice by application of periodical water stress and potassium fertilization. Molecules 19:1795–1819

Zhang G, Wang Y, Guo Y, Zhao Y, Kong F, Li S (2015) Characterization and mapping of QTLs on chromosome 2D for grain size and yield traits using a mutant line induced by EMS in wheat. Crop J 3:135–144

Zhu JK (2002) Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Ann Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 53:247–273

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by annual grants from Shadid Beheshti University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmadikhah, A., Marufinia, A. Effect of reduced plant height on drought tolerance in rice. 3 Biotech 6, 221 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0542-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0542-3