Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most diagnosed cancer in the USA, and African Americans experience disproportionate CRC diagnosis and mortality. Early detection could reduce CRC incidence and mortality, and reduce CRC health disparities, which may be due in part to lower screening adherence and later stage diagnosis among African Americans compared to whites. Culturally tailored interventions to increase access to and uptake of CRC stool-based tests are one effective strategy to increase benefits of screening among African Americans. The objectives of this study were to obtain feedback from African Americans on CRC educational materials being developed for a subsequent behavioral clinical trial and explore participants’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about CRC and CRC screening. Seven focus groups were conducted between February and November 2020. Participants were African Americans recruited through community contacts. Four focus groups were held in-person and three were conducted virtually due to Covid-19 restrictions. Participants ranked CRC educational text messages and provided feedback on a culturally tailored educational brochure. A focus group guide with scripted probes was used to elicit discussion and transcripts were analyzed using traditional content analysis. Forty-two African Americans participated. Four themes were identified from focus group discussions: (1) knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs on CRC and CRC screening; (2) reliable sources of cancer education information; (3) cultural factors affecting perspectives on health; and (4) community insights into cancer education. Participant input on the brochure was incorporated in content creation. Engaging African American community members to qualitatively examine cancer prevention has value in improving implementation strategy and planning for behavioral clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer detected and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the USA, with approximately 147,950 new cases diagnosed annually and 53,000 deaths [1]. While CRC incidence has declined in patients over 50 years old over the last two decades, the rates have increased in younger aged patients [2], prompting the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) to issue a draft statement lowering the screening age to 45 [3]. Model-based approaches estimate that over 50% of CRC deaths in the USA could be prevented with better adherence to screening recommendations [4, 5]. Evidence-based and cost-effective CRC screening includes colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and stool-based tests [6]. Because of the high survival rate of CRC when detected early, groups like the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable have championed sustained efforts to increase awareness of the importance of screening and early detection to achieve the national screening goal of “80% in every community” [7].

African Americans compared to whites have higher incidence and mortality from CRC and are diagnosed at earlier ages but later stage of disease, leading most medical organizations to recommend CRC screening for African Americans beginning at age 40 to 45 [8, 9]. Despite steady overall declines in CRC incidence and mortality rates across racial and ethnic groups in the USA, the disproportionate burden among African Americans has persisted albeit shrinking, compared to their white counterparts. For example, the CRC incidence rate is approximately 20% higher for African Americans compared to whites [10, 11]. These cancer health disparities may be partially accounted for by different and insurmountable levels or rates of obesity, physical activity, dietary habits, smoking, environmental factors, genetic factors, and access to care (screening, diagnostic, and treatment) [12, 13]. In Florida, where the current study was conducted, Whites reported greater adherence to screening with colonoscopy (69%) compared to African Americans (53%) in 2018 [14]. It is noted however that Florida is non-Medicaid expansion state, and Medicaid expansion has been associated with improvements in colorectal cancer screening for low-income residents and African Americans [15]. According to clinician colleagues at the community health centers in the area, there is a shortage of gastroenterologists who will provide colonoscopy screening to uninsured patients. In addition, in 2020, because of the Covid-19 pandemic, adults are delaying any screening or avoiding diagnostic screening procedures like colonoscopy, and this negative trend is affecting medically underserved populations disproportionately [16]. The 5-year relative survival rate for colon cancer from 2009 to 2015 was 65.4% for African Americans compared to 71.7% for Whites [17]. African American CRC patients have lower survival rates and less localized disease compared to White patients, in part due to later stage at diagnosis, which could be partially addressed with better adherence to screening guidelines and improvements in health care coverage [10]. While CRC death rates across the USA have declined, in southern states, where there are larger populations of African Americans, the decline has been slower compared to Whites [1].

In the USA, colonoscopy is the most thorough test and is often referred to as the “gold standard” for CRC screening. However, because of a shortage of gastroenterologists—especially in rural areas, lack of health care coverage to cover the diagnostic procedure or excess copays and deductibles, and other barriers such as transportation or fear of the test—participation in colonoscopy screening can be challenging for some communities. There have been several studies to examine the potential impact of stool-based testing interventions to increase screening rates among low-income and minority populations since this testing modality is more easily administered and costs less than other tests [18,19,20]. A Cochrane review estimated that the reduction in CRC deaths associated with stool-based testing was approximately 14% [21]. To address CRC health disparities, there needs to be increased outreach and education on the necessity of timely CRC screening for African Americans regardless of the modality. Lowering the screening age may increase uptake but adherence remains a major factor for the annual stool blood test and requires successful intervention approaches [19, 22].

Culturally tailored/targeted interventions to increase annual stool blood tests in African Americans are one strategy to potentially improve adherence to CRC screening according to the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines [23, 24]. According to a systematic review on interventions to increase stool blood testing in African American communities, tailored navigation approaches such as using a patient navigator to contact patients by telephone or in person have resulted in a range of 6 to 36% increases in CRC screening compared to usual care [25]. In another study performed in a large health care system to understand screening uptake in younger populations, a prospective study of fecal immunochemical test (FIT)-mailed screening resulted in a 33% return rate among African Americans between 45 and 50 years old [26]. The objective of this focus group study was to collect feedback on educational components of a planned behavioral research study that will employ community health advisors to increase stool-based testing in African Americans in north Florida. Additionally, we explored the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of focus group participants toward CRC and CRC screening. This study reports the analysis of these focus group discussions among African American community members in two north Florida counties with large proportions of African Americans compared to other counties in the state.

Methods

The data reported in this focus group study are part of a larger behavioral trial that will test the effectiveness of a community health advisor intervention to increase stool-based testing in African Americans between 45 and 64 years of age who are not up-to-date with USPSTF CRC screening guidelines [3]. This would include individuals who have never been screened but are recommended to begin stool-based screening at age 45. The rationale for the upper age limit of 64 for the planned intervention study was to recruit pre-Medicare eligible patients to potentially capture more of the uninsured population. Formative research was conducted with African Americans in this approximate age range to explore knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about CRC and CRC screening, elicit feedback on draft versions of a CRC educational tri-fold brochure, and identify preferred CRC screening educational text messages.

Recruitment

The study team recruited participants for seven focus groups of African Americans in northern Florida: rural Gadsden County, Florida’s only majority African American county and neighboring Leon County, location of the state’s capital, Tallahassee, a mid-size Florida city. Eligible participants could be either male or female and needed to identify as African American. The first four groups were held in person, and the last three groups were held online because of Covid-19 mitigation precautions. Focus group recruitment was facilitated through contacts with church and community leaders, and the in-person groups were held at three different African American churches in two counties from February to early March 2020. The fourth group was conducted in mid-March 2020 and subsequently university Covid-19 restrictions on staff travel and society-wide communicable disease prevention efforts essentially precluded further in-person meetings. The study team submitted an amendment to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and proceeded to recruit individuals to participate in Zoom meetings for three additional focus groups. After conducting seven focus groups, the content of the discussions reached thematic saturation [27].

All participants provided informed consent to join in the focus group discussions. Twenty-nine participants joined the four in-person focus groups, and an additional 13 participants joined the online focus groups. The research project was approved by the Florida A&M University IRB.

Data Collection

The study team developed a focus group guide with questions and scripted probes composed of approximately 21 questions (Table 1). In addition, participants completed demographic questions (including place of birth) and a rating form with a series of 13 educational text messages on colon cancer using a 5-point Likert scale to measure agreement. The term “colon cancer” was a more familiar term than “colorectal cancer,” so we primarily used “colon cancer” in the focus group questions. The opening questions focused on sources of health information, knowledge and awareness of colon cancer, colon cancer prevention, and whether they thought colon cancer was a problem in their community. The focused set of questions asked participants to discuss whether colon cancer screening could be improved by education on the disease, whether they were familiar with any specific symptoms and screening methods, and what types of prevention and screening methods such as colonoscopy and stool-based tests they had heard about.

The next set of questions asked participants to review the draft version of the educational brochure. Learner verification for the educational brochure was used to obtain feedback about the materials to ensure they resonated with the target audience. The considerations of learner verification, culture, and literacy used in our study was informed by the recommendations of Meade and colleagues [28] to positively impact patient education and outreach through accessible materials. It involves verifying or reviewing the materials with the audience on several elements: acceptability, attraction, understanding, self-efficacy, and persuasion. Learner verification is especially helpful during the development phase of educational materials/media and offers multiple feedback loops for improvement and revision to ensure content is understood and culturally appropriate for the intended audience. Participants were asked about the attractiveness and content of the brochure. They were also asked to comment on comprehension, cultural appropriateness, and persuasion characteristics, as well as to provide suggestions on improving the content. The focus group concluded with questions about who they were likely to trust delivering health messages, most important points discussed in the focus group, and any final questions or concerns. The co-moderator presented a summary of the discussion at the end.

The focus groups were led by a skilled facilitator and a co-moderator to handle the recording equipment and the forms. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed by a transcription company. The only difference in procedure for the online focus groups was that participants completed demographic forms online rather than paper and pencil, and the transcription was created automatically by the videoconference platform. The co-moderator’s role was the same in terms of taking notes and summarizing the discussion at the end. All focus group participants received a retail grocery gift card in the amount of $20 either in person or through the mail and an educational infographic handout from the American Cancer Society.

Data Analysis

First, an internal report summarizing each focus group was prepared by the co-moderator. Interview transcripts were analyzed using MAXQDA® (Marburg, Germany) computer software. The lead author (JL) employed a traditional content analysis approach to develop a coding scheme to attach meaningful codes to blocks of text [29, 30]. A codebook was developed in MAXQDA® to operationalize and define the code categories. The lead author (JL) and one co-author (MV) then recoded the transcripts using the codebook to reach agreement on coding procedures and coding accuracy. The lead author and two co-authors (MV, OM) then convened to resolve any coding discrepancies and collaboratively agree on the overarching themes and subthemes from the focus groups. Qualitative feedback on the brochures and quantitative ratings of the text message preferences were analyzed and incorporated to improve these educational materials for use in the subsequent behavioral clinical trial.

Results

Participants

The study recruited a total of 42 African Americans who participated in seven focus groups. Table 2 provides the demographic characteristics of participants, and only two participants listed a foreign country of birth. A majority of participants were female (81%), between the ages of 50 and 59 years (55%) and most had completed at least some college (67%). There was one participant aged 41 and one participant aged 70. All other participants were in the age range 45–64 as was requested of community partners by the research team to aid with recruitment efforts. Half of the participants lived in Tallahassee, and the other half lived in neighboring Gadsden County. Focus groups ranged in size from three to nine participants, with fewer participants per group in the online focus groups than the in-person focus groups. The length of the focus group discussions ranged from 36 to 82 min, with an average of approximately 52 min. Table 3 summarizes the participant ratings for possible text messages intended for use in the intervention phase. Shorter text messages about the benefits of screening were rated slightly higher over text messages which pointed to health disparities or CRC rates among African Americans. Out of 13 text messages, participants rated “Screening for colon cancer saves lives” the highest.

Summary of Findings

After analyzing the focus group transcripts, four major themes emerged from the coding categories: (1) knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs on CRC and CRC screening; (2) reliable sources of cancer education information; (3) cultural factors affecting perspectives on health; and (4) community insight on cancer education materials. The results presented here are organized around these themes. Direct quotes from participants illustrate the themes and sub-themes in the following section.

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs About CRC and CRC Screening

The theme around knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about CRC and CRC screening encompassed codes on CRC family history, CRC screening, CRC symptoms, diet and exercise to prevent cancer, and perceived causes of CRC. There were varying levels of knowledge about CRC (Table 4). Participants were familiar with various symptoms they had heard about such as blood in the stool and rectal bleeding. Conversations frequently mentioned older family members or celebrities—e.g., the actor Chadwick Boseman had recently passed from CRC at the age of 43—in the context of their knowledge about the disease. In terms of explanatory models of the disease, there was the belief that diet, stress, family history, and environmental factors were possible causes for someone to receive a CRC diagnosis. Because there were tobacco fields in the area, some participants discussed the history of farm work in their family as being a cause of cancer in the community. Eating a “Southern food” diet was viewed as unhealthy because these foods could be high in fat resulting from how they were prepared. Some participants stated that a diet high in red meat was related to CRC and that a diet high in vegetables/fiber was beneficial. Also, there were frequent discussions about concerns with modern industrial food production, in particular “chemicals” and “hormones” in the processed foods. Regarding CRC incidence, several groups discussed that African American men were more likely to receive a CRC diagnosis than women. Four participants stated that they had no knowledge about CRC and CRC screening.

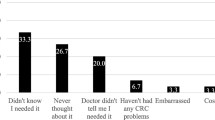

Many participants were familiar with the age to begin screening, either 50 or earlier at 40 or 45. Some participants wanted to have more information about the recommended age if CRC was more common in African Americans, and why they were not being told to start screening at age 45. There was no reported knowledge of the upper limit of age 75 for CRC screening. There were more frequent discussions of the colonoscopy procedure than other types of CRC screening, and the common aversion to the bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy, but there was acknowledgement that removing precancerous polyps was a positive outcome. Regarding colonoscopy, there also was discussion about concerns surrounding the decision to undergo the exam with or without anesthesia. There was also some aversion indicated for the stool-based test, which might lead some to delay completing the home test. Some participants described their own or their family members’ or friends’ awkwardness or embarrassment about completing the stool-based test, sometimes using words like “gross” or “nasty” to describe it. Another reason cited for not completing CRC screening was the absence of symptoms, signaling a lack of urgency to get the CRC screening scheduled and completed. It was expressed across groups that there was a lack of awareness about CRC and CRC screening in the community. Many participants stated that there was much greater promotion and awareness about breast cancer than CRC.

Reliable Sources of Cancer Education Information

The theme of reliable sources of cancer education information included discussions of both one’s personal network and media sources of information. Participants mostly preferred and trusted cancer education information from their doctors whom they believed would be in the best position to answer their questions (Table 5). Some participants also believed and trusted information from family or friends, survivors of colorectal cancer whom they knew, and from cancer advocacy organizations. Other sources of information included trusted websites, television programs, magazines, and social media posts from their social network. When sources of information such as magazine articles specifically addressed the needs of African Americans, participants highlighted these examples in their responses.

Cultural Factors Affecting Perspectives Toward Health

Several topics discussed were grouped into a category labeled “cultural factors” which included codes relating to fear of cancer, African American perspectives, and religious beliefs (Table 6). One topic discussed in several groups was fear of a cancer diagnosis. Fear of receiving a diagnosis was listed as a reason for not completing or for delaying CRC screening; one participant described her fear of learning of a CRC diagnosis through screening as well as her fear about not knowing (i.e., not completing her screening). Some participants valued screening to help them have peace of mind; however, other participants pointed out that sometimes it was better not to know if someone had cancer because that could lead to a negative mindset or catastrophic thinking. Moreover, among men, there were some statements which indicated perceived stigma around the colonoscopy procedure alluding to threats to masculinity. Because the in-person focus groups were conducted in Christian churches, many discussions around health and illness addressed religious beliefs and the importance of faith in God. Because of challenges with health care access and awareness of persistent health disparities, several participants expressed the dual importance of both praying to ask God for healing and seeking timely medical care when confronted by a cancer diagnosis. These sentiments may not necessarily be unique to this faith community, however.

Community Insights on Cancer Education

The focus groups generated additional qualitative data about CRC screening educational resources which consisted of a draft version and subsequently modified educational tri-fold brochure. For the original draft version of the brochure, participants read through the entire brochure to ensure comprehension of the material in terms of health literacy. Participants liked the colors and the graphics of the human anatomy and the colon showing polyps. Some said that they wanted a short testimonial and liked the photos featuring famous African Americans who had died from CRC (e.g., Eartha Kitt). Focus group participants also indicated a preference for pictures of well-known community members rather than stock photos. Due to copyright restrictions, the final version did not feature photos of celebrities, but had two photos of couples; one photo was of a couple people knew in the community and the other was a stock photo.

Following the brochure revisions from the earlier focus groups, one online focus group participant commented: “I like the brochure. I love the photos, you’re showing a couple, not just men and not just women, a couple, and at different ages as well, which is great.” Another online participant in a different focus group also commented on the pictures and colors: “I think what you have is good with the pastor and his wife, you know, local people. People can identify and know that they are just everyday people. And, I like the fact that it’s very colorful and eye catching.” The final version highlighted statistics about African Americans and CRC and featured clear and colorful graphics showing the anatomy of the colon, the digestive system, and descriptions of colonoscopy and the stool-based test. The back cover of the brochure listed information for accessing resources from the American Cancer Society and the National Cancer Institute. On the inside panel, relating to questions on cancer screening, there was a testimonial called Earl’s Story, which read, “It’s a test no one looks forward to, but it’s important to talk about it. I feel like I dodged a bullet.” There was also a short section above the testimonial about not letting fear be a factor, stating the fact that those who found CRC early had a greater than 90% survival outcome.

Discussion

This qualitative study adds to the literature on knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes of CRC and CRC screening among African American community members in northern Florida and how such community participation may help to inform content and strategies for a cancer education intervention. While the bulk of the focus group discussions were in response to questions specifically about CRC, several other related topics were discussed including access to health care, health challenges specific to African Americans, quality of health care, and sources of reliable health information. These discussions provided the facilitators an opportunity to share CRC educational materials with participants on a topic rarely discussed in the community. In addition, the engagement prompted valuable input and feedback for the creation of the intervention brochure and preferences for a series of educational text messages to influence behavior toward CRC screening. During the online focus groups, participants confirmed that the brochure and its contents were understandable and culturally appropriate. Collecting qualitative feedback on materials and strategies prior to refinement of a behavioral intervention has been associated with increased community engagement and improved effectiveness of planned intervention strategies [31]. Discussion of CRC, and cancer in general, can be an uncomfortable topic which might elicit fear or have stigma attached to it, especially around the topic of screening, so incorporating community health advisors into cancer screening intervention programs is a promising approach to address concerns community members may have about screening [32,33,34].

Participants expressed limited communication with providers on the topic of CRC and CRC screening. For many women who participated in the groups, there was the perception that there were less discussions about CRC, with more emphasis usually placed on breast cancer education and screening mammography. Focus group participants opined that “everything costs,” suggesting the perception that even the effort to obtain accurate health information, during a doctor visit for example, had a monetary cost attached to it. Participants mostly relied on accurate health information coming from their health care providers in terms of health information seeking. Moreover, some believed that to receive recommended preventive health care required patients to be advocates for themselves in the health system. One participant specifically mentioned an African American gastroenterologist as providing personalized care. In a focus group study with African Americans who had a first-degree relative with CRC, a strong physician recommendation served as a cue to action for completing CRC screening [35]. Therefore, it is important for patients to discuss CRC and CRC screening with their primary care physician to ensure that they receive timely screening based on their risk profile.

The focus group discussions revealed several barriers to screening. Participants stated that many community members, especially those who are uninsured and lack a medical home, may not receive CRC home screening mailings and may be unaware of the availability of no-cost or low-cost stool blood screening through community clinics, and consequently, participants indicated the need for more effective communication of the availability of CRC home screening. There were some negative attitudes to CRC screening because of lack of insurance, lack of symptoms, fear, and embarrassment; however, this was more pronounced among men than women. Reasons for delaying screening, such as the belief that CRC was more common in men than women and the absence of symptoms, among other individual and systematic barriers, align with findings from other qualitative studies conducted with African Americans on this topic [31, 34, 36,37,38]. Although the brochure did not address cancer risk in men explicitly, the testimonial in the brochure was titled Earl’s Story and described how CRC screening was a test no one looks forward to, but is important to talk about, emphasizing social norms.

There were some limitations to the focus groups in terms of difficulties recruiting enough men to participate in the focus groups and challenges relating to the discontinuation of in-person focus groups following the institution of Covid-19 protocols in mid-March 2020. The research team had to adjust their recruitment strategy and recruit an additional three focus groups to participate in Zoom meetings which delayed focus group scheduling. The major advantage of holding Zoom meetings is the technological feature of producing transcripts and recording videos that could be reviewed later. The disadvantages of virtual rooms include the lack of visual cues used in focus groups to indicate who is ready to speak next. However, no differences were detected in terms of the information participants were willing to share. Demographic surveys were completed using an online survey tool instead of paper surveys and did not present barriers for participants. The only technical challenge for focus group participants who joined virtual rooms consisted of not being able to turn on their videos and view the brochure. However, the brochure file was emailed to them prior to the meeting. Based upon their feedback, most had reviewed it before the meeting.

Conclusions

The qualitative methods used to gather data in the focus group discussions allowed participants to express their knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about CRC and CRC screening, offer insight into risk factors and concerns present in their community, and provide perspectives from their own personal experiences and interactions with the health care system. The limited availability of easily accessible cancer education information was a concern raised across focus groups, with many suggestions provided on how to increase community awareness, both in terms of general information on CRC and the availability of affordable stool-based screening. These concerns were addressed in the intervention materials. Engaging African American community members to qualitatively examine cancer prevention educational strategies was valuable for improving our program implementation and planning for the behavioral clinical trial. The planned intervention has the anticipated impact of improving the quality of CRC screening education and of changing negative attitudes leading to enhanced uptake of CRC screening among African Americans and thus reducing disparities in cancer health outcomes.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Sauer AG, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A (2020) Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 70(3):145–164

Loomans-Kropp HA, Umar A (2019) Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in young adults. J Cancer Epidemiol 2019:9841295

The Lancet Gastroenterology, Hepatology (2021) USPSTF recommends expansion of colorectal cancer screening. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 6(1):1

Meester RG, Doubeni CA, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Goede SL, Levin TR, Quinn VP, MvBallegooijen DA, Corley, and A. G. Zauber. (2015) Colorectal cancer deaths attributable to nonuse of screening in the United States. Ann Epidemiol 25(3):208-213 e201

Zauber AG (2015) The impact of screening on colorectal cancer mortality and incidence: has it really made a difference? Dig Dis Sci 60(3):681–691

Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, Flowers CR, Guerra CE, LaMonte SJ, Etzioni R et al (2018) Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin 68(4):250–281

Wender R, Brooks D, Sharpe K, Doroshenk M (2020) The National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable: past performance, current and future goals. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 30(3):499–509

Carethers JM (2015) Screening for colorectal cancer in African Americans: determinants and rationale for an earlier age to commence screening. Dig Dis Sci 60(3):711–721

Paquette IM, Ying J, Shah SA, Abbott DE, Ho SM (2015) African Americans should be screened at an earlier age for colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 82(5):878–883

DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Alcaraz KI, Jemal A (2016) Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA Cancer J Clin 66(4):290–308

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2020) Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 70(1):7–30

Augustus GJ, Ellis NA (2018) Colorectal cancer disparity in African Americans: risk factors and carcinogenic mechanisms. Am J Pathol 188(2):291–303

Carethers JM (2018) Clinical and genetic factors to inform reducing colorectal cancer disparitites in African Americans. Front Oncol 8:531

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015) BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/. Accessed 11 Jan 2021

Zerhouni YA, Trinh QD, Lipsitz S, Goldberg J, Irani J, Bleday R, Haider AH, Melnitchouk N (2019) Effect of Medicaid expansion on colorectal cancer screening rates. Dis Colon Rectum 62(1):97–103

Nodora JN, Gupta S, Howard N, Motadel K, Propst T, Rodriguez J, Schultz J et al (2020) The COVID-19 pandemic: identifying adaptive solutions for colorectal cancer screening in underserved communities. J Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djaa117

Surveillance Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) (2018) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2017 Sub (2000–2015) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969–2016 Counties, ed. DCCPS National Cancer Institute, Surveillance Research Program

Stone R, Stone JD, Collins T, Barletta-Sherwin E, Martin O, Crosby R (2019) Colorectal cancer screening in African American HOPE VI public housing residents. Fam Community Health 42(3):227–234

Cusumano VT, May FP (2020) Making FIT count: maximizing appropriate use of the fecal immunochemical test for colorectal cancer screening programs. J Gen Intern Med 35(6):1870–1874

Gupta S, Coronado GD, Argenbright K, Brenner AT, Castaneda SF, Dominitz JA, Green B et al (2020) Mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach for colorectal cancer screening: summary of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-sponsored Summit. CA Cancer J Clin 70(4):283–298

Holme O, Bretthauer M, Fretheim A, Odgaard-Jensen J, Hoff G (2013) Flexible sigmoidoscopy versus faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening in asymptomatic individuals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD009259

Liang PS, Wheat CL, Abhat A, Brenner AT, Fagerlin A, Hayward RA, Thomas JP, Vijan S, Inadomi JM (2016) Adherence to competing strategies for colorectal cancer screening over 3 years. Am J Gastroenterol 111(1):105–114

Arnold CL, Rademaker A, Wolf MS, Liu D, Hancock J, Davis TC (2016) Third annual fecal occult blood testing in community health clinics. Am J Health Behav 40(3):302–309

Horne HN, Phelan-Emrick DF, Pollack CE, Markakis D, Wenzel J, Ahmed S, Garza MA et al (2015) Effect of patient navigation on colorectal cancer screening in a community-based randomized controlled trial of urban African American adults. Cancer Causes Control 26(2):239–246

Roy S, Dickey S, Wang HL, Washington A, Polo R, Gwede CK, Luque JS (2021) Systematic review of interventions to increase stool blood colorectal cancer screening in African Americans. J Community Health 46(1):232–244

Levin TR, Jensen CD, Chawla NM, Sakoda LC, Lee JK, Zhao WK, Landau MA et al (2020) Early screening of African Americans (45–50 years old) in a fecal immunochemical test-based colorectal cancer screening program. Gastroenterology 159(5):1695-1704 e1

Krueger RA, Casey MA (2000) Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research, 3rd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Meade CD, Menard J, Martinez D, Calvo A (2007) Impacting health disparities through community outreach: utilizing the CLEAN look (culture, literacy, education, assessment, and networking). Cancer Control 14(1):70–77

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–1288

Renz SM, Carrington JM, Badger TA (2018) Two strategies for qualitative content analysis: an intramethod approach to triangulation. Qual Health Res 28(5):824–831

May FP, Whitman CB, Varlyguina K, Bromley EG, Spiegel BM (2016) Addressing low colorectal cancer screening in African Americans: using focus groups to inform the development of effective interventions. J Cancer Educ 31(3):567–574

Santos SL, Tagai EK, Scheirer MA, Bowie J, Haider M, Slade J, Wang MQ, Holt CL (2017) Adoption, reach, and implementation of a cancer education intervention in African American churches. Implement Sci 12(1):36

Holt CL, Litaker MS, Scarinci IC, Debnam KJ, McDavid C, McNeal SF, Eloubeidi MA, Crowther M, Bolland J, Martin MY (2013) Spiritually based intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among African Americans: screening and theory-based outcomes from a randomized trial. Health Educ Behav 40(4):458–468

Lumpkins CY, Vanchy P, Baker TA, Daley C, Ndikum-Moffer F, Greiner KA (2016) Marketing a healthy mind, body, and soul: an analysis of how African American men view the church as a social marketer and health promoter of colorectal cancer risk and prevention. Health Educ Behav 43(4):452–460

Griffith KA, Passmore SR, Smith D, Wenzel J (2012) African Americans with a family history of colorectal cancer: barriers and facilitators to screening. Oncol Nurs Forum 39(3):299–306

Farr DE, Haynes VE, Armstead CA, Brandt HM (2020) Stakeholder perspectives on colonoscopy navigation and colorectal cancer screening inequities. J Cancer Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01684-2

Luque JS, Wallace K, Blankenship BF, Roos LG, Berger FG, LaPelle NR, Melvin CL (2018) Formative research on knowledge and preferences for stool-based tests compared to colonoscopy: what patients and providers think. J Community Health 43(6):1085–1092

Sly JR, Edwards T, Shelton RC, Jandorf L (2013) Identifying barriers to colonoscopy screening for nonadherent African American participants in a patient navigation intervention. Health Educ Behav 40(4):449–457

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the invaluable assistance of the U54 RCMI Community Engagement Core headed by Dr. Sandra Suther and our community partners who included Reverend Joseph Jones, Ms. Karusha Sharpe, Mrs. Arrie Battle, Ms. Miaisha Mitchell, Ms. Nettie Palmore, and Ms. Agnes Coppin for providing guidance with identifying/enlisting participants and organizing the meetings. We also acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Alexandria Washington with help facilitating in-person focus groups. Finally, we acknowledge support of the U54 RCMI Center Office – Ms. Leola Hubert-Randolph and Ms. Gloria O. James–Academic Support Services, Florida A&M University College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Institute of Public Health and U54 RCMI Principal Investigator, Dr. Karam F. Soliman.

Funding

This article was supported by funding from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54 MD007582. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luque, J.S., Vargas, M., Wallace, K. et al. Engaging the Community on Colorectal Cancer Screening Education: Focus Group Discussions Among African Americans. J Canc Educ 37, 251–262 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-021-02019-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-021-02019-w