Abstract

Aim-Background

The rapid evolution of minimally invasive surgery has demonstrated the need for training surgical skills outside the operating room using animal model simulators. There is increasing evidence that educating trainee surgeons by simulation is preferable to traditional operating-room training methods with actual patients.

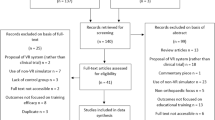

Methods

A critical and systematic review of the literature was performed to assess whether medical simulators can represent a current validated tool for surgical training. A search of the literature was conducted using the PubMed search engine. Further articles were obtained by manually searching the reference lists of identified papers.

Results

Training by simulation can provide some unique benefits, such as greater control over the training procedure and more easily defined metrics for assessing proficiency, reducing costs and risks to patients. Virtual reality simulators are now playing an increasing role in surgical training, Satisfactory and pertinent levels of physical realism, case complexity and performance assessment can lend simulation as an effective advanced surgical training and assessment tool. While the aim of all simulators is to the training of psychomotoric skills, some simulators also allow training in decision-making and anatomical orientation.

Conclusion

In the not too distant future, virtual reality simulators may constitute a integral tool in the training and validation of surgical skills and monitoring of training progress. Proper validation and increased recognition by the medical profession of their potential value are crucial if they are to be incorporated in surgical training curricula.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bergamaschi R. [Farewell to “see one, do one, teach one”?]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2001;121:2798.

Cosman PH, Cregan PC, Martin CJ, Cartmill JA. Virtual reality simulators: current status in acquisition and assessment of surgical skills. ANZ Journal of Surgery 2002;72:30–34.

Melvin WS, Johnson JA, Ellison EC. Laparoscopic skills enhancement. Am J Surg 1996;172:377–379.

Gallagher AG, Richie K, McClure N, McGuigan J. Objective psychomotor skills assessment of experienced, junior, and novice laparoscopists with virtual reality. World J Surg 2001;25:1478–1483.

Gallagher AG, Ritter EM, Lederman AB, et al. Video-assisted surgery represents more than a loss of three-dimensional vision. Am J Surg 2005;189:76–80.

Moorthy K, Munz Y, Sarker SA, Darzi A. Objective assessment of technical skills in surgery. BMJ 2001;327:1032–1037.

Shaffer DW, Dawson SL, Meglan D, et al. Design principles for the use of simulation as an aid in interventional cardiology training. Min Invas Ther & Allied Technol 2001;10:75–82.

Hutchins M, Adcock M, Stevenson D, et al. The design of perceptual representations for practical networked multimodal virtual training environments. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; 2005 July 22-7; Las Vegas, USA. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis Group LLC (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc), 2005.

Bridges M, Diamond DL. The financial impact of teaching surgical residents in the operating room. Am J Surg 1999;177:28–32.

Peters JH, Fried GM, Swanstrom LL, et al. Development and validation of a comprehensive program of education and assessment of the basic fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery. Surgery 2004;135:21–27.

Satava RM. Historical review of surgical simulation-a personal perspective. World J Surg 2008;32:141–148.

Dent JA, Harden RM. A practical guide for medical teachers, 2nd ed. Elsevier: Dundee; 2005.

Aggarwal R, Undre S, Moorthy K, Vincent C, Darzi A. The simulated operating theatre: comprehensive training for surgical teams. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13(Suppl 1):i27–i32.

Blumenthal D Making medical errors into “medical treasures”. JAMA 1994;272:1867–1868.

Bradley P, Bligh J. Clinical skills centres: where are we going? Med Educ 2005;39:649–650.

Bradley P. The history of simulation in medical education and possible future directions. Med Educ 40 2006;254–262.

Gallagher AG, Ritter EM, Champion H, et al. Virtual reality simulation for the operating room: proficiency-based training as a paradigm shift in surgical skills training. Ann Surg 2005;241:364–372.

Kneebone RL, Scott W, Darzi A, Horrocks M. Simulation and clinical practice: strengthening the relationship. Med Educ 2004;38:1095–1102.

Kneebone RL, Nestel D, Vincent C, Darzi A. Complexity, risk and simulation in learning procedural skills. Med Educ 2007;41:808–814.

Reznick RK, MacRae H. Teaching surgical skills-changes in the wind. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2664–2669.

Ziv A, Wolpe PR, Small SD, Glick S. Simulation-based medical education: an ethical imperative. Acad Med 2003;78:783–788.

Seymour NE. VR to OR: a review of the evidence that virtual reality simulation improves operating room performance. World J Surg 2008;32:182–188.

Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Hart IR, et al. Simulation technology for health care professional skills training and assessment. JAMA 1999;282:861–866.

Kneebone R. Simulation in surgical training: educational issues and practical implications. Med Educ 2003;37:267–277

McDougall EM Validation of surgical simulators. J Endourol 2007;21:244–247.

Bajka M, Tuchschmid S, Streich M, Fink D, Szekely G, Harders M. Evaluation of a new virtual-reality training simulator for hysteroscopy. Surg Endosc 2008; doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9927-7.

Carter FJ, Schijven MP, Aggarwal R, et al. Consensus guidelines for validation of virtual reality surgical simulators. Surg Endosc 2005;19:1523–1532.

Gallagher AG, Ritter EM, Satava RM. Fundamental principles of validation, and reliability: rigorous science for the assessment of surgical education and training. Surg Endosc 2003;17:1525–1529.

Dunkin B, Adrales G, Apelgren K, Mellinger J. Surgical simulation: a current review. Surg Endosc 2007;21:357–366.

Gerson LB. Evidence-based assessment of endoscopic simulators for training. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2006;16:489–509.

Larsen CR, Soerensen JL, Grantcharov TP, et al. Effect of virtual reality training on laparoscopic surgery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;338:b1802.

Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, et al. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach 2005;27:10–28.

Gettman MT, Le CQ, Rangel LJ, Slezak JM, Bergstralh EJ, Krambeck AE. Analysis of a computer based simulator as an educational tool for cystoscopy: subjective and objective results. J Urol 2008;179:267–271.

Shah J, Darzi A. Virtual reality flexible cystoscopy: a validation study. BJU Int 2002;90:828–832.

Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van HR, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;296:1094–1102.

Spencer FC. Teaching and measuring surgical techniques- the technical evaluation of competence. Am Coll Surg 1978;63:9–12.

Dankelman J, Chmarra MK, Verdaasdonk EG, Stassen LP, Grimbergen CA. Fundamental aspects of learning minimally invasive surgical skills. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 2005;14:247–256.

Enochsson L, Isaksson B, Tour R, et al. Visuospatial skills and computer game experience influence the performance of virtual endoscopy. J Gastrointest Surg 2004;8:876–882.

Grantcharov TP, Bardram L, Funch-Jensen P, Rosenberg J. Impact of hand dominance, gender, and experience with computer games on performance in virtual reality laparoscopy. Surg Endosc 2003;17:1082–1085.

Hutchinson L. Educational environment. Br Med J 2003;326:810–812.

Lacorte MA, Risucci DA. Personality, clinical performance and knowledge in paediatric residents. Med Educ 1993;27:165–169.

Mitchell M, Srinivasan M, West DC, et al. Factors affecting resident performance: development of a theoretical model and a focused literature review. Acad Med 2005;80:376–389.

Reich DL, Uysal S, Bodian CA, et al. The relationship of cognitive, personality, and academic measures to anesthesiology resident clinical performance. Anesth Analg 1999;88:1092–1100.

Ringsted C, Skaarup AM, Henriksen AH, Davis D. Persontask-context: a model for designing curriculum and intraining assessment in postgraduate education. Med Teach 2006;28:70–76.

Schwind CJ, Boehler ML, Rogers DA, et al. Variables influencing medical student learning in the operating room. Am J Surg 2004;187:198–200.

Williams S, Dale J, Glucksman E, Wellesley A. Senior house officers’ work related stressors, psychological distress, and confidence in performing clinical tasks in accident and emergency: a questionnaire study. Br Med J 1997;314:713–718.

Kneebone R. Evaluating clinical simulations for learning procedural skills: a theory-based approach. Acad Med 2005;80:549–553.

Teunissen PW, Stapel DA, Scheele F, et al. The influence of context on residents’ evaluations: effects of priming on clinical judgment and affect. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2007; doi: 10.1007/s10459-007-9082-2.

Vincent C. Understanding and responding to adverse events. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1051–1056.

Farmer E, van Rooij J, Riemersma J, Jorna P, Moraal J. Handbook of simulator-based training. England: Ashgate, 1999.

Kneebone R, Nestel D, Wetzel C, et al. The human face of simulation: patient-focused simulation training. Acad Med 2006;81:919–924.

Kneebone R, Kidd J, Nestel D, Asvall S, Paraskeva P, Darzi A. An innovative model for teaching and learning clinical procedures. Med Educ 2002;36:628–634.

Coleman J, Nduka CC, Darzi A. Virtual reality and laparoscopic surgery. Br J Surg 1994;81:1709–1711.

Wilson MS, Middlebrook A, Sutton C, Stone R, McCloy RF. MIST VR: a virtual reality trainer for laparoscopic surgery assesses performance. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1997;79:403–404.

Larsson A. An open and flexible framework for computer aided surgical training. Stud Health Technol Inform 2001;81:263–265.

Schijven MP, Jakimowicz JJ. Introducing the Xitact LS500 laparoscopy simulator: toward a revolution in surgical education. Surg Technol Int 2003;11:32–36.

Smith CD, Farrell TM, McNatt SS, Metreveli RE. Assessing laparoscopic manipulative skills. Am J Surg 2001;181:547–550.

Gallagher AG, Satava RM. Virtual reality as a metric for the assessment of laparoscopic psychomotor skills. Learning curves and reliability measures. Surg Endosc 2002;16:1746–1752.

Rosser JC, Rosser LE, Savalgi RS. Skill acquisition and assessment for laparoscopic surgery. Arch Surg 1997;132:200–204.

Kothari SN, Kaplan BJ, DeMaria EJ, Broderick TJ, Merrell RC. Training in laparoscopic suturing skills using a new computer-based virtual reality simulator (MIST-VR) provides results comparable to those with an established pelvic trainer system. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2002;12:167–173.

Chmarra MK, Grimbergen CA, Dankelman J. Systems for tracking minimally invasive surgical instruments. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 2007;16:328–340.

Seymour NE, Gallagher AG, Roman SA, O’Brien MK, Andersen DK, Satava RM. Analysis of errors in laparoscopic surgical procedures. Surg Endosc 2004;18:592–595.

Van Sickle KR, Baghai M, Huang IP, Goldenberg A, Smith CD, Ritter EM. Construct validity of an objective assessment method for laparoscopic intracorporeal suturing and knot tying. Am J Surg 2008;196:74–80.

Eubanks TR, Clements RH, Pohl D, et al An objective scoring system for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg 1999;189:566–574.

Martin JA, Regehr G, Reznick R, et al. Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. Br J Surg 1997;84:273–278.

Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med 1990;65:S63–S67.

Schijven MP, Jakimowicz JJ, Broeders IA, Tseng LN. The Eindhoven laparoscopic cholecystectomy training course—improving operating room performance using virtual reality training: results from the first E.A.E.S. accredited virtual reality trainings curriculum. Surg Endosc 2005;19:1220–1226.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Papanikolaou, I.G. Assessment of medical simulators as a training programme for current surgical education. Hellenic J Surg 85, 240–248 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13126-013-0047-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13126-013-0047-z