Abstract

Purpose

Competency-based medical education (CBME) relies on frequent workplace-based assessments of trainees, providing opportunities for conscious and implicit biases to reflect in these assessments. We aimed to examine the influence of resident and faculty gender on performance ratings of residents within a CBME system.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study took place from August 2017 to January 2021 using resident assessment data from two workplace-based assessments: the Anesthesia Clinical Encounter Assessment (ACEA) and Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs). Self-reported gender data were also extracted. The primary outcome—gender-based differences in entrustment ratings of residents on the ACEA and EPAs—was evaluated using mixed-effects logistic regression, with differences reported through odds ratios and confidence intervals (α = 0.01). Gender-based differences in the receipt of free-text comments on the ACEA and EPAs were also explored.

Results

In total, 14,376 ACEA and 4,467 EPA assessments were analyzed. There were no significant differences in entrustment ratings on either assessment tool between men and women residents. Regardless of whether assessments were completed by men or women faculty, entrustment rates between men and women residents were not significantly different for any postgraduate year level. Additionally, men and women residents received strengths-related and actions-related comments on both assessments at comparable frequencies, irrespective of faculty gender.

Conclusion

We found no gender-based differences in entrustment ratings for both the ACEA and EPAs, which suggests an absence of resident gender bias within this CBME system. Given considerable heterogeneity in rater leniency, future work would be strengthened by using rater leniency-adjusted scores rather than raw scores.

Résumé

Objectif

La formation médicale fondée sur les compétences (FMFC) repose sur des évaluations fréquentes des stagiaires en milieu de travail, ce qui donne l’occasion de refléter les préjugés conscients et implicites dans ces évaluations. Notre objectif était d’examiner l’influence du genre des résident·es et des professeur·es sur les évaluations de la performance des résident·es au sein d’un système de FMFC.

Méthode

Cette étude de cohorte rétrospective s’est déroulée d’août 2017 à janvier 2021 à l’aide des données d’évaluation des résident·es provenant de deux évaluations en milieu de travail : L’évaluation de l’anesthésie clinique par événement (ACEA – Anesthesia Clinical Encounter Assessment) et les Actes professionnels non supervisés (APNS). Des données autodéclarées sur le genre ont également été extraites. Le critère d’évaluation principal, soit les différences fondées sur le genre dans les cotes de confiance des résident·es sur l’ACEA et les APNS, a été évalué à l’aide d’une régression logistique à effets mixtes, les différences étant rapportées par les rapports de cotes et les intervalles de confiance (α = 0,01). Les différences fondées sur le genre dans la réception des commentaires en texte libre sur l’ACEA et les APNS ont également été explorées.

Résultats

Au total, 14 376 évaluations ACEA et 4467 évaluations APNS ont été analysées. Il n’y avait pas de différences significatives dans les cotes de confiance obtenues avec l’un ou l’autre des outils d’évaluation entre les résidents et les résidentes. Indépendamment du genre de la personne réalisant l’évaluation, les taux de confiance entre les résidentes et les résidents n’étaient pas significativement différents pour toutes les années de formation postdoctorale. De plus, les résident·es ont reçu des commentaires liés à leurs forces et leurs actes sur les deux évaluations à des fréquences comparables, quel que soit le genre du corps professoral.

Conclusion

Nous n’avons constaté aucune différence fondée sur le genre dans les cotes de confiance telles qu’évaluées par les ACEA et les APNS, ce qui suggère une absence de préjugés genrés envers les résident·es au sein de ce système de FMFC. Compte tenu de l’hétérogénéité considérable en matière de clémence des évaluateurs et évaluatrices, les travaux futurs seraient plus fiables s’ils utilisaient des scores ajustés en fonction de ladite clémence plutôt que des scores bruts.

Similar content being viewed by others

The presence and prevalence of explicit or implicit gender biases in medical education may undermine resident assessment. Gender bias, as it relates to assessment, refers to how culturally established gender roles and beliefs consciously or unconsciously impact our perceptions and actions. With the transition to competency-based medical education (CBME), there has been a renewed focus on gender bias as the CBME educational paradigm relies on frequent workplace-based assessments (WBAs) of resident trainees from a variety of assessors to support competence development and inform competence committee decision-making regarding promotion and completion of training.1,2,3,4 Workplace-based assessments, which serve to gather evidence of clinical competence observed in the authentic clinical environment, take many forms, including daily encounter tools which consider different competencies across a case or shift as well as Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) which are “whole-task” assessments of specialty-specific tasks that trainees can be trusted to do with varying levels of supervision.5,6 Competency-based medical education’s emphasis on regular observation, feedback, and assessment provides ample opportunities for both explicit and implicit biases to reflect in these assessments. Ultimately, gender bias may negatively impact resident progression, delay licensure, cause undue trainee stress, and influence women’s decisions to reject a career in academic medicine.7,8,9

Several studies have reported that, compared with men, women residents are systematically underrated on WBAs in obstetrics and gynecology, emergency medicine, and internal medicine training programs.10,11,12,13 Additionally, research has revealed gender-based differences in feedback, including feedback consistency and traits ascribed to residents, with one study reporting that feedback to family medicine trainees included more negative comments for women trainees than it did for men trainees.14,15,16 Gender may also influence residents’ experience of feedback.17 Nevertheless, these findings are not consistent across specialties, context, or training level, and some studies reported no gender-based differences.18,19,20,21

The impact of gender bias threatens the validity of WBAs and may limit the academic progression of vulnerable trainees. To date, there is no literature evaluating gender bias among anesthesia resident trainees, and data on EPAs are limited across specialties. Our primary aim was to compare the level of entrustment in women vs men residents. Secondarily, we sought to examine whether faculty gender and assessment type (daily encounter WBA and EPA) influences performance ratings of residents and the number of comments provided to residents.

Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Toronto Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (Toronto, ON, Canada) on 13 May 2021 (Protocol Number: 37490). Informed consent was waived. This retrospective, cross-sectional study used faculty assessments of anesthesia residents submitted from August 2017 to January 2021, including the previously validated Anesthesia Clinical Encounter Assessment (ACEA), our program’s daily encounter WBA tool, and EPAs developed by the Association of Canadian University Departments of Anesthesiology to support the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons’ Competence by Design (CBD) initiative.1,22 The Department of Anesthesia supported the implementation of EPA and ACEA assessments via e-mails sent out to faculty. In addition, these tools were presented to each hospital site during grand rounds, for a total of one presentation each at eight sites. Supporting educational videos were published by the Post MD Education office of the Temerty Faculty of Medicine (University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada).Footnote 1 During the study period, there was no training on gender bias related to EPA or ACEA assessments.

Alongside these assessment data, we used self-reported gender data (originally collected as female, male, or non-binary) that are publicly available on the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO) websiteFootnote 2 and were provided by residents and faculty at the time of registration with the CPSO. For conceptual clarity in this study, the sex-linked terms on the CPSO website were rephrased as woman, man, and non-binary. We also collected resident postgraduate year (PGY) and faculty demographic data (i.e., years on faculty, faculty rank) as well as contextual data for each assessment (i.e., hospital site, rotation, on-call status, case complexity). All data were deidentified prior to analysis. This report follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology guidelines.23

Assessment tools

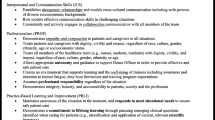

The ACEA is a daily encounter workplace-based assessment for perioperative patient care with strong validity evidence which assesses trainees based on progression to competence using a five-level entrustment-supervision scale (“intervention” to “consultancy level”).1 It comprises an eight-item global rating scale covering various perioperative care elements, an overall rating of independence for the entire case (or shift) and space for free-text feedback. Faculty receive a reminder email to complete the ACEA online following each resident encounter during an anesthesia rotation. In contrast, EPAs are resident-initiated with a defined number to be completed at each stage of CBME training—49 EPAs overall.22 Residents may approach any faculty member to complete an EPA assessment online following a clinical encounter, both during anesthesia and off-service rotations. The EPAs also characterize entrustment on a five-level entrustment-supervision scale (from “intervention” to “proficient”) and provide room for free-text feedback. Additionally, each assessment tool includes separate text boxes for the provision of free-text strengths-related comments and comments on areas or actions to improve (actions-related comments). Residents have access to their ACEA and EPA assessment data, and the program’s competency committee uses the data to inform resident progression and promotion decisions.

Data handling and exclusion criteria

We extracted ACEA data from August 2017 to January 2021 and EPA data from September 2018 to January 2021. We excluded assessments that were started and not completed, assessments provided by non-faculty (e.g., co-residents, chief residents, and fellows), and assessments from faculty with missing data (e.g., academic designation).

Outcome definitions

For the ACEA and EPAs, we converted the five-level retrospective entrustment-supervision scale into a binary scale, whereby levels 4 or 5 denote achievement of “entrustment/entrustable,” and levels 1, 2 or 3 signify “entrustment not achieved.” Additionally, for each assessment, we extracted data on the presence or absence of strengths-related comments, actions-related comments, and any comments (i.e., strengths- or actions-related). We did not perform qualitative analysis of the comments as this was out of scope. As anesthesia residents rotate through several other specialties (i.e., emergency medicine, intensive care, surgery, pediatrics, internal medicine), we categorized EPA assessments completed during these nonanesthesia specialty rotations as “off-service” compared with assessments completed during anesthesia “on-service” rotations.

Statistical analysis

To investigate potential evidence of gender bias, we used mixed-effects logistic regression to evaluate the association of entrustability (dichotomized as entrustable or not entrustable) with resident gender, faculty gender, and PGY, including all two-way interactions, with random intercepts for residents and faculty to account for their heterogeneity in performance and rater leniency/severity, respectively. We used the binary outcome of “entrustable” and “not entrustable” as this aligned with the real-world use of the tools. Our residency competency committee progresses and advances students based on achieving entrustability. We adjusted for case complexity (low–medium clinical complexity, high clinical complexity, or not indicated), on-call status (ACEA only), rotation service (anesthesia or off-service; EPA only), faculty years of experience (scaled and centred), and site. Covariates included in the regression models were selected based on their availability in the CPSO and assessment data sets, presumed clinical and/or educational relevance, and with the goal of isolating and estimating differences in assessment outcomes that may be attributable to resident gender. First, related to our primary aim, we modelled outcomes irrespective of faculty gender; second, we incorporated faculty gender into the models. These mixed-effects models were used to estimate marginal effects, representing adjusted rates of entrustment between women and men residents for each PGY. Marginal effects were reported as adjusted odds ratios, which are useful when outcomes are common and have previously been employed in studies of gender bias in trainee assessments, with 99% confidence intervals.19,24 Analyses were conducted in R version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the lme4 (version 1.1-27.1) and emmeans (version 1.7.3) packages.25 Models were fit using maximum likelihood estimation with the bobyqa optimizer and model fit was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. Standard errors were calculated from the information matrix. All hypothesis tests were two-tailed (α = 0.01). Adjusted results are reported.

Results

Characteristics of assessments

There were 15,416 ACEA assessments collected over 42 months across eight hospital sites. After exclusion criteria, 14,376 ACEAs were available for analysis (Figure, panel A), representing assessments of 58 women residents (median [interquartile range (IQR)], 83 [56–120] assessments per resident) and 99 men residents (88 [556–133] assessments per resident). Anesthesia Clinical Encounter Assessments were provided by 105 women faculty (32 [10–61] assessments per faculty) and 206 men faculty (37 [18–69] assessments per faculty). Overall, 1,535 (10.7%) of ACEAs were provided by women faculty assessing women residents (women faculty-women resident), 2,840 (19.8%) were women faculty assessing men residents (women faculty-men resident), 3,529 (24.6%) were men faculty assessing women residents (men faculty-women resident) and 6,472 (45.0%) were men faculty assessing men residents (men faculty-men resident). There were no assessments from nonbinary residents or faculty. Table 1 shows the characteristics of ACEA assessments, including those completed on-call, with additional details reported in Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] eTable 1. There was no difference in years of experience among faculty completing ACEA assessments for women and men residents. The ratio of men to women residents increased significantly from 1.48 in PGY 1 to 2.13 in PGY 5 (ESM eTable 2).

Of 8,048 EPAs collected over 29 months, 3,581 met the exclusion criteria, resulting in 4,467 EPAs available for analysis (Figure, panel B), representing assessments of 29 women residents (median [IQR], [27–78] assessments per resident) and 45 men residents (59 [44–90] assessments per resident). Entrustable Professional Activities assessments were provided by 92 women faculty (10 [4–19] assessments per faculty) and 198 men faculty (12 [5–22] assessments per faculty). Overall, 493 (11.0%) of EPAs were from women faculty-women resident gender dyads, 926 (20.7%) were women faculty-men resident, 1,093 (24.5%) were men faculty-women resident, and 1,955 (43.8%) were men faculty-men resident. As with the ACEA, there were no assessments from nonbinary residents or faculty. Approximately 99% of EPAs (4,389/4,428) were for anesthesia vs off-service rotations (Table 1). There was no difference in the years of experience among faculty completing EPA assessments for women residents compared with men residents.

Entrustment-supervision ratings

Overall, 7,424/14,376 (51.6%) of ACEA and 4,126/4,467 (92.4%) of EPA assessments were entrustable. Women residents were entrustable on 2,487/5,064 (49.1%) and 1,467/1,586 (92.5%) of ACEA and EPA assessments, respectively, compared with 4,937/9,312 (53.0%) and 2,659/2,881 (92.3%) for men residents. The model-estimated proportions of men and women residents rated as entrustable on the ACEA and EPA across postgraduate years are presented in Table 2, with full model details available in ESM eTables 3 and 4. Across PGYs, entrustment rates on the daily encounter ACEA rose in a stepwise manner, whereas entrustment rates on the EPA exceeded 90% for all PGYs. Within each PGY, the proportion of assessments rated as entrustable for men and women residents were not significantly different on either assessment tool (P > 0.05). Interestingly, for both the ACEA and EPA, the random effects for faculty were larger than those for residents, suggesting that the variance in rater leniency/severity among faculty was greater than the variance in performance among residents (ESM eTables 3 and 4).

Influence of faculty gender on entrustment-supervision ratings

Resident entrustment rates by women faculty are shown in Table 3, and those for men faculty are presented in Table 4. Full model details are reported in ESM eTables 3 and 4. Regardless of whether assessments were completed by men or women faculty, entrustment rates between men and women residents were not different for any PGY level (P > 0.01).

Comments

On both the ACEA and EPA, strengths-related comments were provided by faculty for the vast majority (> 93%) of assessments for both men and women residents in each PGY (Table 5). In contrast, actions-related comments were provided to men and women residents on approximately 80% of assessments in PGY 1, with linearly diminishing frequency in subsequent PGYs. Actions-related comments were more frequently provided on the ACEA than the EPA assessments, which is probably because of the different nature of the two assessments. Raw differences in the receipt of comments between men and women residents for each PGY seldom exceeded 2%, suggesting that both genders receive approximately the same number of comments on their assessments.

Influence of faculty gender on comments

Trends in the provision of free-text comments examined separately for women faculty (ESM eTable 5) and men faculty (ESM eTable 6) aligned with those observed for all faculty assessors. Critically, women and men residents in each PGY were provided with comments on their assessments at similar rates, regardless of faculty gender.

Discussion

Our study revealed no gender-based differences in the entrustment of men and women residents for both the ACEA, a daily encounter workplace-based assessment tool, and EPAs. Our exploration of how often faculty provided open-ended comments for men and women residents also suggested no gender-based differences in the assessment of anesthesiology residents. Regarding the entrustment ratings, our analyses revealed that the variance in rater leniency/stringency was greater than the variance in performance across ratees, as other investigators have found.26,27,28 This suggests that the use of rater leniency-adjusted scores, as opposed to raw assessments scores, may be preferable in many research and educational applications.29,30

At our institution, the validated ACEA tool and EPAs are used to monitor overall progression and inform decisions to promote residents to the next CBD training stage. It is reassuring that both tools did not show a difference in the entrustment of women vs men residents. Consistent with our findings, a recent study evaluating gender bias in EPAs of general surgery residents found no differences in the entrustment levels among men and women residents.20 Of note, a study by Spring et al. reported that women anesthesia residents rotating through intensive care units at the University of Toronto between 2010 and 2017 received lower ratings than their men counterparts.19 These findings happened in years when there was a lower proportion of women anesthesia residents contributing to the assessment data and prior to the implementation of validated assessment tools. Similarly, our study shows a gender gap in representation of women residents, which seems to be narrowing in more recent years. More equal representation of women residents and faculty may assist with normalizing their assessments and experience in training.9 Nevertheless, Spring et al. did not evaluate the influence of faculty gender on the differences in resident assessments.19 The use of structured entrustment-based tools for assessing behaviours indicative of competence may mitigate against implicit gender bias by having assessors focus on discrete behaviours or tasks and the desired outcomes of learning.31,32

Our exploratory analysis of the provision of open-ended assessment comments to men and women residents also suggested no gender-based differences, which is encouraging. Nevertheless, this requires further investigation, particularly qualitative text analysis that goes beyond the presence or absence of comments. Previously, content analysis of narrative comments provided to emergency medicine residents found that women residents were provided with inconsistent feedback, particularly related to autonomy and leadership.15 This suggests there may be implicit bias in expected behaviour cues among men faculty and expectations that are not verbalized to or known by women residents. While the majority of faculty positions are still held by men, these differences in feedback may lead to poorer mentoring and coaching for women residents, which could contribute to differential training experiences and may influence women residents’ confidence and career decisions.33,34,35 Padilla et al. reported that, despite similar faculty EPA ratings across genders, women surgical residents’ self-assessed EPA scores were lower than their men counterparts’ scores, which may reflect a gender-based confidence gap.20 Nevertheless, it is encouraging that the ACEA and EPAs may be effectively reducing the influence of such biases on entrustment ratings and, therefore, not impeding women resident progression and promotion.32

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare data from a daily encounter WBA tool (i.e., ACEA) and EPAs within the same trainee cohort as well as the first to examine gender-based discrepancies in EPA assessments of anesthesia residents. We included many assessments across training levels, increasing the generalizability of the results. The three-year study period with data from multiple hospital sites also helps to ensure that our results were not related to discrepancies within a specific trainee cohort or at one training site.

Our study also has several limitations. The first is the absence of nonbinary individuals in our data set. In a 2020 survey of perceptions on gender equity in anesthesia department leadership, 35/11,746 (< 0.1%) responding anesthesiologists from 148 countries identified as nonbinary, with a third reporting mistreatment at their local institution because of their gender identity.33 It is possible that residents and/or faculty may have chosen not to disclose their gender as nonbinary, limiting our ability to evaluate potential gender bias faced by this minority group. While we did not observe any gender-based differences in the presence or absence of comments left on assessments, we did not perform a qualitative analysis of the content of comments. Qualitative studies looking at faculty assessments have shown evidence of discrepancies based on gender, including discrepancies in the positivity of comments and differential wording used in free-text comments.15,36,37,38 Further analysis of these comments may yield information that may assist faculty and program directors in identifying patterns of implicit bias. In addition, the role of repeated or continuous contact between individual residents and faculty, in the context of implicit bias, warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, it is reassuring that there were no differences in entrustment ratings between same-level women and men residents on both the ACEA, a daily encounter workplace-based assessment, and EPAs. The apparent absence of gender-based differences in the receipt of comments is also encouraging; however, future qualitative evaluation of narrative comments would be useful to explore this issue further.

Notes

University of Toronto Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. What is an entrustable professional activity (EPA) for anesthesia?—Dr Lisa Bahrey explains, 2017. Available from URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HS5BUiAMKW8 (accessed March 2023).

College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. COVID-19 updates. Available from URL: http://www.cpso.on.ca (accessed March 2023).

References

Kealey A, Alam F, Bahrey LA, Matava CT, McCreath GA, Walsh CM. Validity evidence for the Anesthesia Clinical Encounter Assessment (ACEA) tool to support competency-based medical education. Br J Anaesth 2022; 128: 691–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.12.012

Friedman Z, Bould MD, Matava C, Alam F. Investigating faculty assessment of anesthesia trainees and the failing-to-fail phenomenon: a randomized controlled trial. Can J Anesth 2021; 68: 1000–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-01971-x

Dubois DG, Lingley AJ, Ghatalia J, McConnell MM. Validity of entrustment scales within anesthesiology residency training. Can J Anesth 2021; 68: 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01823-0

Bailey K, West NC, Matava C. Competency-based medical education: are Canadian pediatric anesthesiologists ready? Cureus 2022; 14: e22344. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.22344

Schumacher DJ, Cate OT, Damodaran A, et al. Clarifying essential terminology in entrustment. Med Teach 2021; 43: 737–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2021.1924365

Weller JM, Coomber T, Chen Y, Castanelli DJ. Key dimensions of innovations in workplace-based assessment for postgraduate medical education: a scoping review. Br J Anaesth 2021; 127: 689–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.06.038

Edmunds LD, Ovseiko PV, Shepperd S, et al. Why do women choose or reject careers in academic medicine? A narrative review of empirical evidence. Lancet 2016; 388: 2948–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01091-0

Welten VM, Dabekaussen KF, Davids JS, Melnitchouk N. Promoting female leadership in academic surgery: disrupting systemic gender bias. Acad Med 2022; 97: 961–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000004665

Bosco L, Lorello GR, Flexman AM, Hastie MJ. Women in anaesthesia: a scoping review. Br J Anaesth 2020; 124: e134-–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.12.021

Dayal A, O'Connor DM, Qadri U, Arora VM. Comparison of male vs female resident milestone evaluations by faculty during emergency medicine residency training. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177: 651–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9616

Galvin SL, Parlier AB, Martino E, Scott KR, Buys E. Gender bias in nurse evaluations of residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 126: 7S–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001044

Brienza RS, Huot S, Holmboe ES. Influence of gender on the evaluation of internal medicine residents. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004; 13: 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1089/154099904322836483

Klein R, Julian KA, Snyder ED, et al. Gender bias in resident assessment in graduate medical education: review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med 2019; 34: 712–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04884-0

Loeppky C, Babenko O, Ross S. Examining gender bias in the feedback shared with family medicine residents. Educ Prim Care 2017; 28: 319–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2017.1362665

Mueller AS, Jenkins TM, Osborne M, Dayal A, O'Connor DM, Arora VM. Gender differences in attending physicians' feedback to residents: a qualitative analysis. J Grad Med Educ 2017; 9: 577–85. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-17-00126.1

Ringdahl EN, Delzell JE, Kruse RL. Evaluation of interns by senior residents and faculty: is there any difference? Med Educ 2004; 38: 646–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01832.x

Billick M, Rassos J, Ginsburg S. Dressing the part: gender differences in residents' experiences of feedback in internal medicine. Acad Med 2022; 97: 406–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000004487

Thackeray EW, Halvorsen AJ, Ficalora RD, Engstler GJ, McDonald FS, Oxentenko AS. The effects of gender and age on evaluation of trainees and faculty in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 1610–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2012.139

Spring J, Abrahams C, Ginsburg S, et al. Impact of gender on clinical evaluation of trainees in the intensive care unit. ATS Sch 2021; 2: 442–51. https://doi.org/10.34197/ats-scholar.2021-0048oc

Padilla EP, Stahl CC, Jung SA, et al. Gender differences in entrustable professional activity evaluations of general surgery residents. Ann Surg 2022; 275: 222–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000004905

Zuckerbraun NS, Levasseur K, Kou M, et al. Gender differences among milestone assessments in a national sample of pediatric emergency medicine fellowship programs. AEM Educ Train 2021; 5: e10543. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10543

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Access to copyright-protected CBD documents. Available from URL: https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/documents/cbd/epa-observation-templates-e (accessed November 2022).

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85: 867–72. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.07.045120

Cook TD. Advanced statistics: up with odds ratios! A case for odds ratios when outcomes are common. Acad Emerg Med 2002; 9: 1430–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01616.x

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 2015; 67: 1–48. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1406.5823

Hindman BJ, Dexter F, Kreiter CD, Wachtel RE. Determinants, associations, and psychometric properties of resident assessments of anesthesiologist operating room supervision. Anesth Analg 2013; 116: 1342–51. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e31828d7218

Dexter F, Hadlandsmyth K, Pearson AC, Hindman BJ. Reliability and validity of performance evaluations of pain medicine clinical faculty by residents and fellows using a supervision scale. Anesth Analg 2020; 131: 909–16. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000004779

Dexter F, Ledolter J, Wong CA, Hindman BJ. Association between leniency of anesthesiologists when evaluating certified registered nurse anesthetists and when evaluating didactic lectures. Health Care Manag Sci 2020; 23: 640–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10729-020-09518-0

Dexter F, Ledolter J, Hindman BJ. Measurement of faculty anesthesiologists' quality of clinical supervision has greater reliability when controlling for the leniency of the rating anesthesia resident: a retrospective cohort study. Can J Anesth 2017; 64: 643–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-017-0866-4

Dexter F, Bayman EO, Wong CA, Hindman BJ. Reliability of ranking anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists using leniency-adjusted clinical supervision and work habits scores. J Clin Anesth 2020; 61: 109639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2019.109639

Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach 2010; 32: 638–45. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2010.501190

Sarosi GA Jr, Klingensmith M. Entrustable professional activities, a tool for addressing sex bias and the imposter syndrome? Ann Surg 2022; 275: 230–1. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000005189

Zdravkovic M, Osinova D, Brull SJ, et al. Perceptions of gender equity in departmental leadership, research opportunities, and clinical work attitudes: an international survey of 11 781 anaesthesiologists. Br J Anaesth 2020; 124: e160–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.12.022

Gonzalez LS, Fahy BG, Lien CA. Gender distribution in United States anaesthesiology residency programme directors: trends and implications. Br J Anaesth 2020; 124: e63–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.12.010

Aliaño M, Franco G, Gilsanz F. Gender differences in Anaesthesiology. At what point do we find ourselves in Spain? Results from a Spanish survey [Spanish]. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim (Engl Ed) 2020; 67: 374–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redar.2019.10.012

Brown O, Mou T, Lim SI, et al. Do gender and racial differences exist in letters of recommendation for obstetrics and gynecology residency applicants? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021; 225: e1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.033

Branfield Day L, Miles A, Ginsburg S, Melvin L. Resident perceptions of assessment and feedback in competency-based medical education: a focus group study of one internal medicine residency program. Acad Med 2020; 95: 1712–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003315

Rojek AE, Khanna R, Yim JW, et al. Differences in narrative language in evaluations of medical students by gender and under-represented minority status. J Gen Intern Med 2019; 34: 684–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04889-9

Author contributions

The manuscript is the collaborative work of six authors. Clyde T. Matava developed the concept, Fahad Alam, Alayne Kealey, Lisa A. Bahrey, Graham A. McCreath, and Catharine M. Walsh participated in the manuscript preparation and revision.

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

This article did not receive funding.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Alana M. Flexman, Guest Editor (Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion), Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Matava, C.T., Alam, F., Kealey, A. et al. The influence of resident and faculty gender on assessments in anesthesia competency-based medical education. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 70, 978–987 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02454-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02454-x