Abstract

Purpose

Learning needs are influenced by the stage of learning and medical specialty. We sought to investigate the characteristics of a good clinical teacher in anesthesiology from the medical students’ perspective.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative descriptive study to analyze written comments of medical students about their clinical teachers’ performances. Our analysis strategy was the inductive content analysis method. The results are reported as a descriptive summary with major themes as the final product.

Results

Our study identified four themes. The first theme, teachers’ individual characteristics, includes characteristics that are usually more related to students’ subjective experiences and feelings. The second theme, teachers’ characteristics that advance student learning, seems to be one of the most important contributions to learning because it increases the practice of procedural skills. The third theme, teachers’ characteristics that prepare students for success, shows characteristics that facilitate students’ learning by promoting a healthy and safe environment. Lastly, the fourth theme, characteristics related to teaching approaches, includes characteristics that can guide clinical teachers more objectively.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the written comments of medical students identified many characteristics of a good clinical teacher that were organized in four different themes. These themes contribute to expand on existing understandings of clinical teaching in the anesthesiology clerkship environment, and add new interpretations that can be reflected upon and explored by other clinical educators.

Résumé

Objectif

Les besoins d’apprentissage sont influencés par le stade d’apprentissage et la spécialité médicale. Nous avons cherché à étudier les caractéristiques d’un bon enseignant clinique en anesthésiologie selon la perspective des étudiants en médecine.

Méthode

Nous avons mené une étude descriptive qualitative pour analyser les commentaires écrits des étudiants en médecine sur les performances de leurs enseignants cliniques. Notre stratégie d’analyse était la méthode inductive d’analyse de contenu. Les résultats sont présentés sous forme de résumé descriptif avec les principaux thèmes comme produit final.

Résultats

Notre étude a identifié quatre thèmes. Le premier thème, les caractéristiques individuelles des enseignants, comprend des caractéristiques qui sont habituellement davantage liées aux expériences subjectives et aux sentiments des étudiants. Le deuxième thème, les caractéristiques de l’enseignant qui font progresser l’apprentissage des étudiants, semble être l’une des contributions les plus importantes à l’apprentissage parce qu’elle augmente la pratique des compétences procédurales. Le troisième thème, les caractéristiques de l’enseignant qui préparent les étudiants à la réussite, présente des caractéristiques qui facilitent l’apprentissage des étudiants en favorisant un environnement sain et sécuritaire. Enfin, le quatrième thème, les caractéristiques liées aux approches pédagogiques, comprend des caractéristiques qui peuvent guider les enseignants cliniques de manière plus objective.

Conclusion

Notre analyse des commentaires écrits des étudiants en médecine a identifié de nombreuses caractéristiques d’un bon enseignant clinique qui étaient organisées en quatre thèmes différents. Ces thèmes contribuent à élargir les connaissances existantes de l’enseignement clinique dans l’environnement de stage clinique en anesthésiologie et ajoutent de nouvelles interprétations qui peuvent inciter d’autres éducateurs cliniques à y réfléchir et à les explorer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The question “What makes a good clinical teacher in medicine?” has long been a frequent topic in the literature.1,2,3,4,5 Being a good clinical teacher is a complex phenomenon and the defining traits may never be fully understood.6,7 Nevertheless, studies have identified some common characteristics of a good clinical teacher in medicine, such as medical knowledge, technical skills, a supportive learning environment, communication skills, and enthusiasm.1 Stimulating students’ growth and sharing the aspects of being a good physician are considered good qualities according to faculties.3 From the perspectives of learners, personal characteristics, strong educator-learner relationships, and ways to engage learning seem to be important characteristics.8 Regardless of whether those studies considered the learners’ or the faculties’ perspectives, they all suggested that characteristics of a good teacher may vary depending on the type of teaching, the learner, and the medical specialty.

Most studies exploring learners’ perspectives have focused on residents as opposed to medical students.3,8,9,10 Some authors have analyzed faculty evaluations from undergraduate and postgraduate learners; however, they did not make distinctions between the groups.8 Other studies focused their results and discussion on important domains to teach residents, and developed recommendations for excellence in clinical teaching based on residents’ evaluations of their clinical supervisors.11,12 Learners at different stages have different learning needs; therefore, it is important to identify the characteristics that medical students consider valuable to improve their learning.

It is equally important to understand what makes a good clinical teacher within different medical specialties.13 Each specialty has unique aspects and may require different teachers’ characteristics.8,14 For example, in psychiatry, students might find communication with patients a big challenge; therefore, the teachers’ non cognitive skills might be essential to those learners in that specific context. On the other hand, in anesthesiology, students might feel that learning how to intubate a patient is the big challenge; thus, the teacher’s technical skills might be considered a priority for learning.8 The unique aspects of anesthesiology include that teaching usually takes place in the operating room (OR)—a dynamic and fast-paced setting where students often work one-on-one with a supervisor for many consecutive hours.15,16 The anesthesiologist needs to teach a variety of topics and procedural skills while taking care of the patient in unpredictable situations and a constricted period of time.17 Therefore, some clinical teachers’ traits, such as being organized and good in time management, might be considered essential.

Little is known about the perspectives of medical students on what they value as characteristics of good clinical teachers in anesthesiology. Students’ evaluations of their teachers can help the teachers think and reflect about the aspects of good teaching and about their own approach, and it can give insights about the learners’ needs.9,18 Teachers can identify their strengths and weaknesses, set their goals, and plan for changes to increase their efficacy.10,18,19,20 Nevertheless, some authors argue that students’ evaluations for assessing the quality of teaching might be inappropriate because some characteristics of students (i.e., motivation), teachers (i.e., gender), and courses (i.e., workload) could affect the evaluation, even though they are not related to good teaching.21,22,23,24,25 Nevertheless, students’ evaluations about their teachers seem to provide an important view of the program and it may have some value in improving clinical teaching.26,27

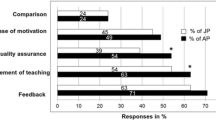

At the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine at McMaster University (MGDSM; Hamilton, ON, Canada), the Medical Student Information System (MedSIS) electronically captures Teacher Effectiveness Scores (TES) on a database. During the anesthesia clerkship, students anonymously evaluate their clinical teachers daily, using quantitatively scaled items and an open-text field designed for general written comments. Once a year, the Department of Anesthesia receives the TES report of each clinical teacher. The TES is collected routinely, the mean score of the quantitatively scaled items of all clinical teachers is calculated, and an overall review is made by the program director. Nevertheless, the Department of Anesthesia does not analyse the qualitative part of the assessment in a consistent and methodical way. Thus, some relevant information might be missed.

Considering the importance of understanding the characteristics of a good clinical teacher from the medical students’ perspectives within anesthesiology, we sought to explore the written comments of medical students about their clinical teachers’ performances at the end of their anesthesia rotation to address the question: “What characteristics make a good clinical teacher in anesthesiology?” Although excellent teaching in anesthesia has become a valuable theme discussed in the literature, most anesthesiologists have little formal education in how to teach medical students.17,28 It therefore was our aim to gain additional valuable insights on teaching medical students in anesthesia programs through the findings of our study.

Methods

Our study was conducted at the MGDSM. We used the qualitative description approach, a qualitative health research approach that stays close to the data to develop a rich description of the phenomenon.29,30,31 Our research was based on naturalistic philosophical assumptions that acknowledge the existence of multiple realities constructed by individuals as they engage with the world and where an understanding of a phenomenon is accessed through the meanings participants give to it.30 Participants were medical students who had finished their anesthesia clerkship rotation during the 2018/2019 academic year. The Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board granted an exemption for ethics review because this study used secondary data. We obtained the data from the TES captured within the MedSIS at the MGDSM.

Our analysis strategy of choice was the inductive content analysis method.32,33,34 First, we read the data twice to achieve immersion and obtain a sense of the whole. Then, the process of coding was initiated. Two authors (L. C. and D. C.) independently divided the comments into smaller parts (meaning units) using the research question as a guide. Next, they condensed the meaning units while preserving the core meaning. As the process continued, codes (names that most describe the condensed meaning units) that reflected one or two key thoughts were generated (see Electronic Supplementary Material, eAppendix). Coding was continued throughout the 173 evaluations. At the end, both researchers (L. C. and D. C.) compared their interpretations and agreement was achieved.

Following the coding, we started the process of categorization.34 We put different codes with similar content into the same category. Then we organized the categories into themes, through a process called abstraction.32,34 Themes are higher order headings that capture the underlying meanings of categories that are grouped together.35

We used several strategies to enhance trustworthiness following techniques based on Lincoln and Guba's criteria (Table 1).36 These strategies included the concepts of credibility, transferability, dependability, confirmability, and reflexivity.37,38,39

We used reflexivity to express the researcher’s influences on the research, purposefully (when it contributed to the research question), paying attention to self-censorship, and during all phases of this research. All researchers (L. C., D. C., and A. W.) were anesthesiologists and educators. D. C. and A. W. have taught in the anesthesia clerkship program. As a team, we used reflexivity and kept a journal throughout the phases of research to consider how our positions may influence our interpretation of the data and to ensure the focus remains on the students’ perspectives.

Results

There were 1,705 evaluations, which were completed by the students. One hundred and seventy-three evaluations included written comments for analysis. There were a total of 201 clinical teachers in the department. The comments were related to 77 of them.

In qualitative description, themes can be considered the final product of the data analysis.35 We identified ten categories and four themes (Table 2).

Theme 1: Teachers’ individual characteristics

The characteristics grouped into this theme were more related to subjective experiences and feelings than concrete examples or facts. One student said, “ID36Footnote 1 was an excellent teacher, owing to her patience, clear communication, and compassion.” Even though the student clearly articulated that “excellent teaching” is linked to “patience, communication, and compassion”, there was no concrete example explaining this relationship. An interesting code under this theme is “organized”. Students always referred to “being organized” as a positive characteristic; however, “being organized” was related to different situations. One learner wrote, “ID111 was organized in his directions for drug set up and for seeing patients prior to the procedure”, linking organization to some clinical skills. Differently, another student said, “ID117 was willing to explain concepts thoroughly and in an organized fashion”, connecting organization to a teaching skill. Moreover, the codes related to patient care and teamwork were put under the professionalism umbrella because “professionalism” was often followed by an explanation on how well patients and/or colleagues were treated. “ID46 maintained a high level of professionalism at all times, with students, patients, and staff.” “Being patient” was the most common personal characteristic mentioned by the students, and it seemed to be related to unique experiences in anesthesiology. Considering that being able to practice procedures seems very important to the medical students (“procedure opportunities” is the most listed code), it is also important that the anesthesiologist is patient enough to let them do it, to ease their anxiety of being in a different environment, and to teach them stressful anesthesiology tasks while performing. “ID92 [...] is very patient, and very good at giving students a chance to attempt procedures”, and “ID128 was patient as it was my first day.”

Theme 2: Teachers’ characteristics that advance student learning

The characteristics in these categories show that clinical teachers have an active role to play in the students’ learning. The anesthesiologists need to show (through words, acts, or expressions) that the student is being encouraged, challenged, engaged, and involved. The students commented, “ID106 engaged me as a learner and as an active member of the team!” and “ID106 encouraged learners to read during breaks and to come back and discuss what was read.” The codes under “stimulating students’ growth” seem to be very important for promoting students’ interests in learning anesthesiology, and increasing their confidence while performing a task. “ID77 challenged me to think broader about the physiological and practical implications involved” and “ID81 encouraged me to draw up medications, intubate patients, and make management plans.”

“Teaching with questions” was another category included in this theme because students often associated the word “question” (“being able to ask questions” or “being able to answer questions”) to describe something that the anesthesiologist did to escalate their learning. “ID138 [...] took the time to ask questions that challenged what I know” and, “ID145 asked excellent questions to help me build my knowledge”. The students’ comments show that it is important to ask questions that are appropriate for their level of knowledge, but challenging at the same time. “The way ID154 asked questions was very respectful and appropriate for my level of learning [...] never shamed me for not knowing the right answer.”

“Making opportunities” to improve practical skills was one of the most important contributions to the medical students’ learning in anesthesiology. Many comments highlighted the relevance of allowing students to perform as many and as diverse procedures as possible. “ID116 let us do a lot of the work, including taking history, putting in EETs [endotracheal tubes], and bag masking patient [...] that's the best way for us to learn.” Some comments also illustrated the importance of actively helping students to increase their practical opportunities. “ID104 is an excellent preceptor who [...] tried to actively find opportunities for students to improve procedural skills.” Interestingly, most of the negative comments also reinforced the importance of letting them perform the tasks. “[ID46] I would have liked more chances to do minor and major tasks” and “ID37 hovered over me during intubations, and rather than offering helpful advice about how to improve my view, he took over as soon as there was any sign that I needed to readjust.”

Theme 3: Teachers’ characteristics that prepare students for success

This theme includes characteristics that facilitate the medical students’ learning in a more subtle way, making it easier for learning to develop, and helping it to happen. Some codes such as “student felt comfortable”, “student felt valued”, and “supporting” are examples of ways that create conditions for medical students to succeed. One student wrote, “ID06 helps students to feel supported in pushing themselves procedurally”, and another one said, “ID16 helped me gain some confidence in my anesthetic skills”. Other words that describe this theme are “walking me through” and “helping me through”. For example, “ID55 helped me through my first successful intubation!” and “ID43 was very helpful and calm in walking me through the intubation process for my first time”. These are examples of characteristics that give the students the foundation for their own improvements. At the same time, some degree of independence seems to be important to them, as wrote by one student, “ID26 was an excellent teacher—he provided lots of autonomy with procedural skills”.

Theme 4: Characteristics related to teaching approaches

This is an important theme because it includes characteristics that can guide clinical teachers more objectively. It shows that simplifying concepts, acronym explanations, and terminologies is a quick way to help medical students. Some of the learning topics that can be considered for discussions are physiology, pharmacology, and basic anesthesia concepts as well as career planning and administration. One student commented on the importance of showing the relevance of anesthesiology, “ID25 [...] would introduce concepts that would be relevant for my field of interest in radiology”. Moreover, case scenarios for discussions and talking about personal experiences may help students to associate theory with the real life of an anesthesiologist. “ID77 also cited personal experiences that gave a realistic flare to the theoretical scenarios.”

Discussion

In our study, we found many characteristics of a good clinical teacher that were similar to the ones discussed in the literature, such as being organized and supportive, providing directions and feedback, showing a plan, and respecting others.1,14,40 Medical knowledge, technical skills, communication skills, and enthusiasm were also noted in our study. Moreover, our findings showed the importance of teachers’ non cognitive characteristics for excellent teaching, as reported in other studies.1,2 Nevertheless, while previous studies found that being enthusiastic and showing good medical knowledge were important characteristics of a good teacher, our findings indicate that other characteristics seemed to be more relevant for clinical teachers in anesthesiology. The characteristics most mentioned by the students were being patient, giving explanations, and making opportunities to improve practical skills.

Some elements for effective learning in anesthesiology include identifying the learners’ basic level of knowledge, helping the students to develop an organization plan, challenging the learner, and providing immediate feedback.40 We found these elements in our study, and they might be related to the anesthesiology context in the OR. The OR environment and anesthesiology as a medical specialty are usually unfamiliar for most medical students before starting their rotation. Therefore, understanding their level of knowledge seems to be a good starting point for these learners. Students also often commented on the importance of “challenging them”. This characteristic could be more related to anesthesiology since challenging learners could stimulate their interest in the discipline, increase their level of confidence, and prepare them for unknown and unpredictable situations in anesthesiology.

Some important elements in teaching in the OR include giving the learner a specific role in the team, maintaining a positive and respectful relationship with the learners, and being responsive to the learners’ needs.16 We found these elements in our study. Interestingly, some authors emphasized the importance of letting the learners participate in the preoperative and postoperative visits, but the students in our study did not mention these elements.16 A possible explanation is that the students might not have been exposed to perioperative visits enough to perceive it as an important contribution to learning. Due to the short time of the anesthesiology rotation, students were, possibly, more focused on what happened in the OR than during the pre and postoperative period.

The main surprise regarding our findings is that our most counted codes were not identified in the literature review as main characteristics of being a good teacher in anesthesiology. The students mentioned, many times, the codes “being patient”, “giving explanations”, and “making opportunities”, but these were not often mentioned in other studies. An explanation for that is that most studies in anesthesiology consider residents or the faculties’ perceptions, instead of students’ opinions. Another explanation is that those characteristics are more related to the peculiarities of the anesthesia clerkship rotation (which is short).

There are limitations of our study that are related to its research design. Qualitative description can provide a rich and complete description of medical students’ opinions; however, the findings may not be generalizable.41 Moreover, although results from qualitative description studies stay closer to the data than other qualitative approaches, our results are nevertheless subject to researchers’ interpretations. Therefore, different results may be found in other institutions because of different interpretations and contexts. Additionally, some authors have problematized the value of students’ evaluations as a criterion for assessing quality of teaching. Gender bias, teaching styles, team environment, timing, and workload affect student evaluations of their teachers. The anonymized nature of our data set limited us from further exploring the influence of these factors. We also cannot determine whether our findings correlate with improved teacher effectiveness. Lastly, defining the characteristics of a good clinical teacher is a complex task which cannot be fully achieved by the reductive process of our content analysis.

Conclusion

Our study used a qualitative descriptive approach to analyse the written comments of medical students about their clinical teachers’ performances to better understand the characteristics of a good clinical teacher in anesthesiology. While most of our findings were similar to those in the literature, the learners in our study consistently identified three characteristics that were not previously described in the literature: “being patient”, “giving explanations”, and “making opportunities to improve practice skills”. It would be important to expand our study to determine whether our findings are associated with measures of improved teacher efficacy, and to compare perceptions between students and residents. Future projects could further explore how sociocultural factors, such as gender, race, interactions with residents, and the clinical environment might also influence the medical students' evaluations of their teachers. Findings from our study contribute to expand on existing understandings of clinical teaching in the anesthesiology clerkship environment, and add new interpretations that can be reflected upon and explored by other clinical educators.

Notes

Numbers replace anesthesiologists’ names. Each number represents a different anesthesiologist.

References

Sutkin G, Wagner E, Harris I, Schiffer R. What makes a good clinical teacher in medicine? A review of the literature. Acad Med 2008; 83: 452-66.

Buchel TL, Edwards FD. Characteristics of effective clinical teachers. Fam Med 2005; 37: 30-5.

Stenfors-Hayes T, Hult H, Dahlgren LO. What does it mean to be a good teacher and clinical supervisor in medical education? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2011; 16: 197-210.

Sapoutzis N, Kalee M, Oosterbaan AE, Wijnen-meijer M. What qualities in teachers are valued by medical students? Beiträge zur Hochschulforschung, 2021; 43: 96-113

Morriss WW, Milenovic MS, Evans FM. Education: the heart of the matter. Anesth Analg 2018; 126: 1298-304.

Tiberius RG, Sinai J, Flak E. The role of teacher-learner relationships in medical education. Int Handb Res Med Educ 2002; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0462-6_19.

Milne D. Can we enhance the training of clinical supervisors? A national pilot study of an evidence-based approach. Clin Psychol Psychother 2010; 17: 321-8.

Harms S, Bogie BJ, Lizius A, Saperson K, Jack SM, McConnell MM. From good to great: learners’ perceptions of the qualities of effective medical teachers and clinical supervisors in psychiatry. Can Med Educ J 2019; 10: e17-26.

Fluit C, Bolhuis S, Grol R, et al. Evaluation and feedback for effective clinical teaching in postgraduate medical education: validation of an assessment instrument incorporating the CanMEDS roles. Med Teach 2012; 34: 893-901.

Fluit CR, Feskens R, Bolhuis S, Grol R, Wensing M, Laan R. Understanding resident ratings of teaching in the workplace: a multi-centre study. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2015; 20: 691-707.

Fluit CR, Bolhuis S, Grol R, Laan R, Wensing M. Assessing the quality of clinical teachers: a systematic review of content and quality of questionnaires for assessing clinical teachers. J Gen Intern Med 2010; 25: 1337-45.

Haydar B, Charnin J, Voepel-Lewis T, Baker K. Resident characterization of better-than- and worse-than-average clinical teaching. Anesthesiology 2014; 120: 120-8.

Bogie BJ, Harms S, Saperson K, McConnell MM. Learning the tricks of the trade: the need for specialty-specific supervisor training programs in competency-based medical education. Acad Psychiatry 2017; 41: 430-3.

Wakatsuki S, Tanaka P, Vinagre R, Marty A, Thomsen JL, Macario A. What makes for good anesthesia teaching by faculty in the operating room? The perspective of anesthesiology residents. Cureus 2018; https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.2563.

Prys-Roberts C, Cooper GM, Hutton P. Anaesthesia in the undergraduate medical curriculum. Br J Anaesth 1988; 60: 355-7.

Jones RW, Morris RW. Facilitating learning in the operating theatre and intensive care unit. Anaesth Intensive Care 2006; 34: 758-64.

Sullivan KR, Rollins MD. Innovations in anaesthesia medical student clerkships. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2012; 26: 23-32.

McKeachie WJ. Student ratings: the validity of use. Am Psychol 1997; 52: 1218-25.

Fluit CV, Bolhuis S, Klaassen T, et al. Residents provide feedback to their clinical teachers: reflection through dialogue. Med Teach 2013; 35: e1485-92.

Boerebach BC. Evaluating clinicians’ teaching performance. Perspect Med Educ 2015; 4: 264-7.

Arah OA, Heineman MJ, Lombarts KM. Factors influencing residents’ evaluations of clinical faculty member teaching qualities and role model status. Med Educ 2012; 46: 381-9.

Benton SL, Cashin WE. Student ratings of teaching: a summary of research and literature. IDEA Cent; (IDEA Paper #50): 1-22. Available from URL: https://ideacontent.blob.core.windows.net/content/sites/2/2020/01/PaperIDEA_50.pdf (accessed January 2022).

Annan SL, Tratnack S, Rubenstein C, Metzler-Sawin E, Hulton L. An integrative review of student evaluations of teaching: implications for evaluation of nursing faculty. J Prof Nurs 2013; 29: e10-24.

Morgan HK, Purkiss JA, Porter AC, et al. Student evaluation of faculty physicians: gender differences in teaching evaluations. J Womens Heal 2016; 25: 453-6.

Miles P, House D. The tail wagging the dog; an overdue examination of student teaching evaluations. Int J High Educ 2015; 4: 116-26.

Boerboom TB, Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DH, Jaarsma DA. How feedback can foster professional growth of teachers in the clinical workplace: a review of the literature. Stud Educ Evaluation 2015; 46: 47-52.

Bush MA, Rushton S, Conklin JL, Oermann MH. Considerations for developing a student evaluation of teaching form. Teach Learn Nurs 2018; 13: 125-8.

Smith AF, Sadler J, Carey C. Anaesthesia and the undergraduate medical curriculum. Br J Anaesth 2018; 121: 993-6.

Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000; 23: 334-40.

Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health 2010; 33: 77-84.

Luciani M, Jack SM, Campbell K, et al. An introduction to qualitative health research. Prof Inferm 2019; 72: 60-8.

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008; 62: 107-15.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15: 1277-88.

Erlingsson C, Brysiewicz P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr J Emerg Med 2017; 7: 93-9.

Sandelowski M, Leeman J. Writing usable qualitative health research findings. Qual Health Res 2012; 22: 1404-13.

Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newburry Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1985: 289-331.

Sandelowski M. Rigor or rigor mortis: the problem of rigor in qualitative research revisited. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1993; 16: 1-8.

Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract 2018; 24: 120-4.

Tracy SJ. Qualitative quality: eight a"big-tent" criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual Inq 2010; 16: 837-51.

Cleave-Hogg D, Benedict C. Characteristics of good anaesthesia teachers. Can J Anaesth 1997; 44: 587-91.

Norman G. Generalization and the qualitative – quantitative debate. Adv Health Sci Educ 2017; 22: 1051-5.

Author contributions

Ligia Cordovani contributed to all aspects of this manuscript, including study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting and editing the article. Daniel Cordovani contributed to the conception of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and editing the article. Anne Wong contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, and drafting and editing the article.

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

None.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Sheila Riazi, Associate Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cordovani, L., Cordovani, D. & Wong, A. Characteristics of good clinical teachers in anesthesiology from medical students’ perspective: a qualitative descriptive study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 69, 841–848 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02234-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02234-z