Abstract

Purpose

Although guidelines can reduce postoperative opioid prescription, the problem of unused opioids persists. We assessed the pattern of opioid prescription and utilization after total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA). We hypothesized that opioid prescription patterns can influence opioid utilization.

Methods

With institutional ethics approval, patients undergoing THA and TKA were enrolled prospectively. Surveys on opioid use were completed at two, six, and 12 weeks after surgery. Patients’ age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Physical Status score, first 24-hr opioid consumption, quantity of opioid prescribed, and quantity of opioid utilized were analyzed to evaluate their effect on opioid consumption, unused opioid, and patient satisfaction.

Results

Patients received prescriptions ranging from 200 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) to 800 MME. Three hundred and thirty THA and 230 TKA patients completed the surveys. Opioid utilization was influenced by the amount of prescribed opioids for both THA and TKA. The percentage of prescribed opioids used (~55% in THA and ~75% in TKA) and the proportion of patients using all prescribed opioids (~22% in THA and ~50% in TKA) were higher after TKA vs THA (P < 0.001 for both). Patients who used opioids for two days or less accounted for most (~50%) of the unused opioid. Patient satisfaction remained high and was not influenced by the amount of prescribed opioid.

Conclusion

This study showed that larger prescriptions are associated with higher opioid consumption. A wide variation in opioid consumption requires approaches to minimize the initial opioid prescription and to provide additional prescriptions for patients that require higher levels of analgesia.

Résumé

Objectif

Bien que les lignes directrices puissent réduire la prescription d’opioïdes postopératoires, le problème des opioïdes inutilisés persiste. Nous avons évalué les schémas de prescription et d’utilisation d’opioïdes après une arthroplastie totale de la hanche (ATH) et une arthroplastie totale du genou (ATG). Nous avons émis l’hypothèse que les schémas de prescription d’opioïdes pouvaient influencer l’utilisation des opioïdes.

Méthode

Avec l’approbation du comité d’éthique de notre établissement, les patients bénéficiant d’une ATH et une ATG ont été recrutés de manière prospective. Les questionnaires sur la consommation d’opioïdes ont été complétés deux, six et 12 semaines après la chirurgie. L’âge, le sexe et le score de statut physique selon l’American Society of Anesthesiologists des patients, ainsi que la consommation d’opioïdes au cours des premières 24 heures postopératoires, la quantité d’opioïdes prescrits et la quantité d’opioïdes utilisés ont été analysés pour évaluer leur effet sur la consommation d’opioïdes, les opioïdes inutilisés et la satisfaction des patients.

Résultats

Les patients ont reçu des ordonnances allant de 200 équivalents de morphine en milligrammes (EMM) à 800 EMM. Trois cent trente patients bénéficiant d’une ATH et 230 patients d’une ATG ont répondu aux questionnaires. L’utilisation des opioïdes a été influencée par la quantité d’opioïdes prescrits pour l’ATH et l’ATG. Le pourcentage d’opioïdes prescrits utilisés (~55 % dans l’ATH et ~75 % dans l’ATG) et la proportion de patients utilisant tous les opioïdes prescrits (~22 % dans l’ATH et ~50 % dans l’ATG) étaient plus élevés après l’ATG vs l’ATH (P < 0,001 pour les deux). Les patients qui ont utilisé des opioïdes pendant deux jours ou moins étaient à l’origine de la plupart (~ 50%) des opioïdes inutilisés. La satisfaction des patients est demeurée élevée et n’a pas été influencée par la quantité d’opioïdes prescrits.

Conclusion

Cette étude a démontré que les ordonnances plus élevées sont associées à une consommation plus élevée d’opioïdes. Une grande variation dans la consommation d’opioïdes nécessite des approches visant à minimiser la prescription initiale d’opioïdes et à fournir des ordonnances supplémentaires aux patients qui nécessitent des niveaux plus élevés d’analgésie.

Similar content being viewed by others

Despite their potential adverse effects, opioids remain one of the most effective analgesics available to treat acute pain after major surgery.1 Several previous studies have shown that large quantities of opioids remain unused by patients after their surgical discharge and acute recovery.2 Given the potential risk for opioid abuse and diversion, clinicians must balance the need for acute pain management against the need to limit excess prescribed opioids.3,4,5

While several factors influence the amount and duration of postoperative opioid use, one factor that has been incompletely assessed is the amount of opioid prescribed at discharge. A retrospective study showed that the quantity of opioid prescribed is associated with higher patient-reported opioid consumption in a broad range of surgeries with different opioid requirements.6 Other studies have examined the relationship between the discharge prescription and the likelihood of refills and persistent use.7 The impact of the amount of opioid prescribed on subsequent opioid utilization has not been prospectively studied in orthopedic surgery for total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA); procedures which have clear pain management requirements and treatment options that including short-term opioid therapy.6,7 Further, to our knowledge, this question has not been evaluated in the Canadian context.

Therefore, we conducted a prospective observational study on opioid use after THA and TKA in both opioid-naïve patients and patients on low-dose opioid before surgery. We studied patterns of opioid consumption in these patients and quantities of unused opioid in relation to the duration of opioid use with actual pill count. We hypothesized that the amount of opioid prescribed would influence post-discharge opioid use in patients undergoing major joint arthroplasty surgery.

Study design and methods

This study was a prospective longitudinal survey of adult patients undergoing primary unilateral hip and knee replacements from May 2017 to October 2018 at a tertiary care teaching hospital (St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada). Following institutional approval by our Research Ethics Board, patients were enrolled through the preadmission anesthesia clinic and consented for study participation before surgery. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: 1) high-dose opioid use before surgery, which was defined as more than 45 oral morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) per day; 2) cognitive impairment or any other condition causing an inability to use “as required” medication for pain control; 3) language barrier preventing completion of patient survey; 4) prolonged hospital stay or discharge to other hospitals/rehabilitation centres post surgery, where pain management is directed by another clinician; 5) bilateral or revision hip and knee arthroplasties.

Data collected in-hospital included patient demographics (age, sex), type of surgery (THA vs TKA), and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Physical Status classification (ASA score) as a measurement of patients’ general health. Opioid was administered during the first 24 hr following surgery as patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), which was the standard of care for pain management at the time of the study. Records from these pumps and the electronic medical record were used as sources of data. Opioid use was converted to MMEs using standard opioid conversion ratios as published in Canadian Guideline for Safe and Effective Use of Opioids for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain.8 Postoperative opioid prescription characteristics including type, dose, and quantity of medication prescribed were abstracted from the electronic medical record.

Patients were surveyed (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] (eAppendices 1–6) by phone or online, depending on patient preference, at two and 12 weeks after surgery. Surveys at six weeks (or four weeks based on date of the orthopedic clinic follow-up appointment) were completed in person when the patient returned to the orthopedic clinic, or by phone or online if no follow-up was scheduled. Patients were asked to provide exact pill counts of unused opioids wherever possible. Patients that were unable to count gave responses as ranges of 1–10, 11–20, or above 20. Other data collected included duration of opioid use, satisfaction score (scale 0 to 10 with 0 as most dissatisfied and 10 as most highly satisfied), potency rating of prescribed opioid (“not strong enough”, “about right”, “too strong”) and need for other prescription opioid.

Completed surveys that included unused opioid pill count and duration of opioid use were analyzed for patterns related to leftover opioids and opioid consumption. In patients that reported different pill counts on their surveys at two, six, and 12 weeks, the pill counts reported closest to the time that the patient stopped using opioid were used as the final pill count. In patients that reported ranges instead of exact pill count, the median number between 1–10 and 11–20 was utilized (i.e., 5 and 15, respectively). The quantities of leftover opioid and opioid consumption were calculated based on the difference between the quantity prescribed and the reported leftover medication, which was then converted to MME of opioid unused and consumed. Data were analyzed based on quintiles of opioid prescribed in terms of morphine milligram equivalents (100.1–200, 200.1–400, 400.1–600, 600.1–800, and > 800 MME) or by opioid MME consumption in the first 24 hr after surgery (0, 0–25, 25.1–50, 50.1–100, 100.1–300, > 300 MME). The total opioid dose is the one reported as MME (calculated by opioid tablet strength and number of tablets prescribed then converted to oral morphine equivalent). The prescribers did not specify a time period on the prescription itself.

Descriptive statistics (total, mean, standard deviation [SD], and median) were used to evaluate clinically relevant relationships between quantities of unused opioid (and opioid consumption) and quantities of opioid prescribed, patient age/sex/ASA score, type of surgery, duration of opioid use, additional opioid prescriptions, and patient satisfaction.

Data are presented as mean (SD); data on percent opioid utilization between THA vs TKA opioid prescription were analyzed using Student t test (Gaussian data) or the Mann–Whitney rank sum test (non-Gaussian data). Data on total opioid utilization between THA vs TKA, percentages of prescribed opioid consumed, percentages of patients using all opioids, and average patient satisfaction scores were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with the Holm–Šídák post hoc test when appropriate. P values < 0.05 were taken to be significant.

Results

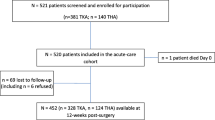

A total of 844 patients scheduled for elective THA and TKA were enrolled between May 2017 and October 2018 (Fig. 1). One hundred and eleven patients were excluded based on exclusion criteria and patient refusal. Out of 733 patients surveyed, 560 surveys (330 THA patients and 230 TKA patients) that provided both opioid pill count and duration of opioid use (Fig. 1) were analyzed for patterns of opioid use. Out of 315 patients that completed the 12-week surveys, 312 patients (184 THA and 128 TKA) reported duration of opioid use and were included in the calculation of opioid use at 12 weeks (Fig. 1).

Prescription patterns

The mean (SD) prescription of postoperative opioids provided to patients at the time of discharge were comparable for THA [497 (249) MME] and TKA [468 (234) MME]. Few patients received very low or very high opioid prescriptions and only 12% of patients received 200 MME or less and 5–6% received > 800 MME (Fig. 2, panel A). Distribution of age, sex and ASA scores were similar in patients with different prescriptions, different quantities of unused opioid, and different durations of opioid use. No clinically meaningful relationship was observed between opioid used in the first 24 hr and the postoperative opioid prescription provided and opioid utilization after hospital discharge for patients undergoing THA or TKA because of wide variation in opioid use (ESM eFig. 1).

Panel A: Assessment of the proportion of patients receiving different levels of opioid prescription after primary hip and knee surgery. Panel B: The relationship between the amount of prescribed opioid and unused opioid in morphine milligram equivalents for different levels of prescribed opioid. The grey shaded area represents the total amount of opioid utilized by all patients undergoing primary hip and knee arthroplasty relative to the prescribed opioids. Panel C: Total opioid dose prescribed and amount unused per patient. The grey area represents the total opioid consumption per patient relative to their opioid prescription.

Residual unused opioid and estimated opioid consumed

The total quantity of opioid prescribed was 272,762 MME for the entire cohort included in this survey. Out of this total, 35% (96,313 MME) of all opioids prescribed were left unused (44% in the THA group and 23% in the TKA group). Patients that received the most commonly prescribed quantity of opioid (400.1–600 MME) accounted for the largest proportion of both unused opioid (open circles or squares) and estimated used opioids (grey shading) and for both THA and TKA (Fig. 2, panel B). When the data were assessed as the total opioid prescribed per patient, as the amount of prescribed opioid increased, the amount of unused opioid increased by a smaller proportion, resulting in a progressive increase in opioid utilization per patient at higher levels of opioid prescription (Fig. 2, panel C, grey shaded area).

When data for estimated total opioid utilization and opioid utilization per patient were plotted, the data showed a peak overall opioid prescription for the mid-range dose (400.1–600 MME) for both THA and TKA (Fig. 3, panel A). When plotted per patient, there was a progressive increase of opioid utilization with increased prescription amount for both THA and TKA (Fig. 3, panel B) with a higher degree of opioid utilization for TKA (P < 0.001).

Panel A: Estimated total opioid utilized for hip and knee arthroplasty. Panel B: Estimated total opioids utilized per patient undergoing hip and knee arthroplasty. Estimated total opioid utilized per patient was significantly less in hip than in knee arthroplasty (ANOVA, P < 0.001). For both hip and knee arthroplasty, the estimated total opioid utilized per patient was significantly greater in patients prescribed 400.1–600, 600.1–800 and > 800.1 morphine milligram equivalents than in patients prescribed 100.1–200 morphine milligram equivalents (Holm– Šídák post-hoc test, P < 0.001).

On average, patients undergoing THA used a lower percentage of opioid prescribed (~ 60%) than those undergoing TKA did (~80%) (Fig. 4, panel A, P < 0.001). A significantly higher percentage of TKA patients (~50%) utilized all of the prescribed opioid than THA patients did (~20%) despite similar quantities of opioids being prescribed [494 (276) MME for THA and 471 (246) MME for TKA] (Fig. 4, P < 0.001, panel B). Patients undergoing THA had a mean (SD) of 278 (223) MME of residual drug while patient undergoing TKA had a mean (SD) of 211(193) MME of residual drug.

Panel A: The overall percentage of consumed or utilized opioid was higher in patients undergoing knee surgery than in patients undergoing hip surgery at all levels of opioid prescription (two-way ANOVA, P < 0.011). Panel B: The proportion of patients utilizing all of their opioid prescription was higher for knee surgery than for hip surgery at all levels of opioid prescription (two-way ANOVA, P < 0.001).

Patients who utilized opioid for prolonged periods

Patients undergoing THA required opioids for shorter duration than patients undergoing TKA did. When assessed by procedure, 32% of patients undergoing THA and 62% of patients undergoing TKA used opioids for more than two weeks (Fig. 5) Patients that used opioids for longer had higher consumption and less unused opioids. A low percentage of patients had no prescribed opioids left after one to two days (4% after THA and 6% after TKA). By two weeks, 27% of THA and 42% of TKA patients had no opioids left. When patients used opioids for more than two weeks, 46% THA and 67% TKA had utilized all of their opioid prescription.

Long-term opioid use (> 12 weeks) was assessed in 312 patients who reported duration of opioid use in the 12-week survey. Three patients who underwent THA (2%) and 16 patients that underwent TKA (13%) were still using opioids at 12 weeks. Of these long-term utilizers, all three THA (100%) and seven of the TKA (44%) patients had been taking low-dose opioid before surgery.

Patients on low-dose opioid before surgery (< 60 MME)

Patients who were on opioids preoperatively were analyzed separately. In this study, 14% of THA and 15% of TKA patients used low-dose opioids before surgery. Compared with opioid-naïve patients, they had higher mean (SD) opioid consumption in the first 24 hr [158 (97) vs 106 (83) MME for THA and 129 (74) vs 79 (65) MME for TKA]. These patients also had less opioids left over (26% vs 46% for THA and 10% vs 26% for TKA). Prior opioid users were more likely to use opioids for more than two weeks (56% vs 28% for THA and 85% vs 59% for TKA) and were more likely to use all of the prescribed opioid (40% vs 19% for THA and 65% vs 46% for TKA). Patients on low-dose opioid before surgery were also twice as likely to rate the opioid as “not strong enough” than opioid naïve patients were (18% vs 9% for THA and 38% vs 23% for TKA).

Patient satisfaction

Despite differences in opioid consumption between THA and TKA, both groups of patients had comparable and high satisfaction scores (Fig. 6). The mean (SD) satisfaction score was 7.8 (2.9) for THA and 7.2 (2.8) for TKA. THA patients more commonly rated their opioid prescription as “too strong” (17% THA vs 6.7% TKA) and less commonly rated it as “not strong enough” (10% of THA vs 25% of TKA). Patients who used opioid for shorter duration and those who utilized a smaller proportion of their prescription accounted for the majority of the unused opioids (ESM eFig. 2). In this survey, 27% of THA and 13.5% of TKA used opioids for two days or less and accounted for 51% and 47% of unused opioid, respectively (ESM eFig. 2). Patients on opioids before surgery were twice as likely to give a low satisfaction score of 0–3 (> 20% vs 10%) than opioid naïve patients were.

Discussion

This prospective cohort study identified an association between the amount of opioids prescribed and the amount of opioids used by patients undergoing THA and TKA. Patients undergoing TKA had higher opioid requirements than those undergoing THA did. For both procedures, the higher level of prescribed opioid did not affect patient satisfaction, suggesting that a more restrictive opioid prescribing pattern may maintain adequate pain control while minimizing residual unused opioid. While no clear association between the first 24-hr opioid consumption and subsequent opioid prescription was identified, the data show a trend for increased prescription with higher 24-hr opioid consumption that may be clinically relevant.

By 12 weeks after surgery, most THA patients did not need opioid analgesics (2%) while a greater proportion of TKA patients remained on opioid therapy (13%). We did not detect an association between opioid use in the first 24 hr post surgery and opioid utilization in the subsequent weeks. Lack of association meant that patients with low or high postoperative opioid consumption could not be preidentified prior to discharge, and their respective prescriptions could not be tailored to their anticipated needs. One proposed strategy is to limit the initial opioid prescription, and provide a second prescription that can be filled upon request; this would minimize unused opioids in the community, while facilitating access to a repeat prescription for those with higher opioid requirements. As hypothesized, the amount of opioid prescribed influenced the amount of opioid used following both THA and TKA. Nevertheless, patient satisfaction was consistently high and did not seem to be influenced by the quantity of opioid prescribed, in keeping with previous studies.9

Our study showed 78% of THA and 51% of TKA patients had unused opioid after surgery, which is in agreement with other published studies.10 In orthopedic joint and spine surgeries, 73% of patients had unused opioid at one-month follow-up and 34% at six-month follow-up.10 In orthopedic, thoracic, obstetric, and general surgeries, 67–92% patients had unused opioids and 42–71% of dispensed opioid went unused in one review A review of six studies involving 810 patients with orthopedic, thoracic, obstetric and general surgical procedures, 67–92% patients had unused opioids and 42–71% of dispensed opioid went unused.2 Therefore, limiting unnecessary opioid prescription is an important step in responsible opioid pain management after surgery.

Our study showed that a small fraction of patients used little to no opioid (about 30% of THA and 15% of TKA). These patients accounted for about 50% of the unused opioid. There are similar findings in other published studies. In a retrospective survey of 2,392 adults within 30 days of surgery, the median consumption was 27% of the prescribed amount, 24% of patients reported no opioid use, and 22% used the entire prescription.6 Prescription guidelines have been developed and published reports showed that these can decrease opioid prescription. The use of procedure-specific prescribing guidelines reduced statewide postoperative opioid prescribing by 50%.4 In laparoscopic cholecystectomy, opioid prescription decreased from 225 MME to 75 MME.3 Nevertheless, in five different outpatient surgeries, although prescription decreased by 53%, only 34% of the prescribed opioid was used.11 Other studies also showed that reducing the prescription did not increase the number of patients requiring a refill.3,7,11 Thus, opioid prescription guidelines may have a significant impact on reducing total quantity of unused opioid in this smaller fraction of patients. The option for small initial prescription with an existing second prescription would facilitate adequate pain management for those patients requiring more prolonged opioid therapy for optimal pain control.

To optimize opioid prescriptions and avoid a “one size fits all” approach, our institution has now implemented a two-stage opioid prescription protocol. In a surgical setting, a small opioid prescription can be dispensed as “part-fill” with the remaining prescription scheduled to be dispensed a few days later if required. Patient education is also needed to guide patients not to fill unneeded opioid prescriptions as 13% TKA and 17% THA in our study did not require any opioids. This finding is similar to those of other studies, where 7–14% of patients filled the prescription but did not use any.2

Even though the risk of chronic opioid use after surgery is relatively low (2% THA and 13% TKA at 12 weeks), it is important to consider because a large number of patients undergo surgeries.12,13 The low incidence of long-term opioid use in this study is not dissimilar to another published study, with 4% of THA patients and 17% of TKA patients being opioid naïve at three months after surgery.14 In surgical literature, the incidence of chronic pain is up to 20% after TKA and pain may plateau between three to six months after surgery.15,16

Evaluation of chronic pain and opioid use in TKA should be put into context. The chronic use of opioids after surgery is multifactorial. These factors may include greater overall body pain, greater affected joint pain, and greater catastrophizing.14 In patients with chronic opioid use, continued use is associated with > 60 MME opioid use before surgery14 or a preoperative opioid dose > 90 MME, filling prescription for oxycodone.15 Male sex, age older than 50 yr, and preoperative history of drug abuse, alcohol abuse, depression, benzodiazepine use, or antidepressant use were also associated with chronic opioid use among surgical patients.17 It should also be noted that larger initial opioid prescriptions have been shown to be associated with greater risk of prolonged use.18 Furthermore, the impact of prior opioid use on the duration of postoperative opioid requirement must be considered.14

A limitation of our study is that it was performed at a single centre. As such, our findings may not be generalizable to other centres. Furthermore, the exact opioid consumption could not be calculated for patients who received additional opioid prescriptions. Nevertheless, the lack of precise opioid consumption data in patients with higher opioid requirements and for those patients who received prescription refills does not affect our key finding that a large proportion of unused opioid was left by patients with very low opioid requirements. During the study period, about 90% of primary THA and TKA were performed under spinal anesthesia. Patients received acetaminophen in addition to opioid (PCA and/or oral opioid). Gabapentinoids were not used routinely for acute pain management for the duration of this study period. Important patient factors, including catastrophizing and psychological profile assessments, which are useful parameters to predict postoperative pain levels and the need for opioids, were not assessed in this pragmatic study. The loss of patients at the 12-week follow-up suggests that there may be bias and underreporting of chronic opioid use in the study if a larger number of patients that continued to use opioid at 12 weeks did not respond to survey. Nevertheless, the data did show that patient profiles (age, sex, type of surgery, and use of opioid before surgery) were similar between patients that responded to the survey at 12 weeks and the entire cohort in the survey.

In summary, our study and other published reports emphasize the need to: 1) tailor discharge opioid prescription to meet the wide range of analgesic and opioid requirements to treat acute pain; 2) maximize multimodal nonopioid and nonpharmacological management to minimize opioid requirement; 3) develop minimally invasive surgical approaches to minimize opioid requirement for pain; 4) develop hospital and community-based programs to manage patients with difficult acute pain and increased opioid requirement; and 5) manage patients that develop chronic pain and minimize chronic opioid use.

References

Shanthanna H, Ladha KS, Kehlet H, Joshi GP. Perioperative opioid administration. Anesthesiology 2021; 134: 645-59.

Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, Alexander GC, Wu CL. Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 1066-71.

Howard R, Waljee J, Brummett C, Englesbe M, Lee J. Reduction in opioid prescribing through evidence-based prescribing guidelines. JAMA Surg 2018; 153: 285-7.

Brown CS, Vu JV, Howard RA, et al. Assessment of a quality improvement intervention to decrease opioid prescribing in a regional health system. BMJ Qual Saf 2021; 30: 251-9.

Roberts KC, Moser SE, Collins AC, et al. Prescribing and consumption of opioids after primary, unilateral total hip and knee arthroplasty in opioid-naive patients. J Arthroplasty 2020; 35: 960-5.e1.

Howard R, Fry B, Gunaseelan V, et al. Association of opioid prescribing with opioid consumption after surgery in Michigan. JAMA Surg 2019; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4234.

Sekhri S, Arora NS, Cottrell H, et al. Probability of opioid prescription refilling after surgery: does initial prescription dose matter? Ann Surg 2018; 268: 271-6.

Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. Can Med Assoc J 2017; 189: E659-66.

Hannon CP, Calkins TE, Li J, et al. The James A. Rand Young Investigator's Award: Large opioid prescriptions are unnecessary after total joint arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2019; 34: S4-10.

Bicket MC, White E, Pronovost PJ, Wu CL, Yaster M, Alexander GC. Opioid oversupply after joint and spine surgery: a prospective cohort study. Anesth Analg 2019; 128: 358-64.

Hill MV, Stucke RS, McMahon ML, Beeman JL, Barth RJ Jr. An educational intervention decreases opioid prescribing after general surgical operations. Ann Surg 2018; 267: 468-72.

Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open 2012; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435.

Wylde V, Hewlett S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Persistent pain after joint replacement: prevalence, sensory qualities, and postoperative determinants. Pain 2011; 152: 566-72.

Goesling J, Moser SE, Zaidi B, et al. Trends and predictors of opioid use after total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Pain 2016; 157: 1259-65.

Jivraj NK, Scales DC, Gomes T, et al. Evaluation of opioid discontinuation after non-orthopaedic surgery among chronic opioid users: a population-based cohort study. Br J Anaesth 2020; 124: 281-91.

Wylde V, Beswick A, Bruce J, Blom A, Howells N, Gooberman-Hill R. Chronic pain after total knee arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev 2018; 3: 461-70.

Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176: 1286-93.

Ruddell JH, Reid DB, Shah KN, et al. Larger initial opioid prescriptions following total joint arthroplasty are associated with greater risk of prolonged use. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2021; 103: 106-14.

Author contributions

Bokman Chan, Sarah Ward, Karim S. Ladha, and Gregory M. T. Hare contributed to all aspects of this manuscript, including study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting the article. Bokman Chan, Sarah Ward, Faraj W. Abdallah, Caroline Jones, Angelo Papachristos, Kyle Chin, Karim S. Ladha, and Gregory M. T. Hare contributed to the conception and design of the study. Bokman Chan, Sarah Ward, Caroline Jones, and Angelo Papachristos contributed to the acquisition of data. Bokman Chan, Sarah Ward, Faraj W. Abdallah, Kyle Chin, Karim S. Ladha, and Gregory M. T. Hare contributed to the analysis of data. Bokman Chan, Sarah Ward, Faraj W. Abdallah, Caroline Jones, Angelo Papachristos, Kyle Chin, Karim S. Ladha, and Gregory M. T. Hare contributed to the interpretation of data.

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

Bokman Chan and Karim S. Ladha received funding from the SMH Innovation Fund; Karim S. Ladha and Gregory M. T. Hare received Merit Awards from the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, University of Toronto.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Philip M. Jones, Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12630_2021_2145_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Supplementary file2 (PDF 1337 kb) eFig. 1 No clear relationship was observed between the opioid utilization in the first 24 hr and subsequent opioid utilization in the postoperative period. eFig. 2 Assessment of the distribution of unused opioids following hip and knee surgery

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, B., Ward, S., Abdallah, F.W. et al. Opioid prescribing and utilization patterns in patients having elective hip and knee arthroplasty: association between prescription patterns and opioid consumption. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 69, 953–962 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-02145-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-02145-5