Abstract

Large numbers of South Africans receive social grants (public transfers) or remittances (private transfers), and yet one in four South Africans is food insecure. The purpose of this paper is to address two questions: do social grants and remittances improve food security and nutritional outcomes? If so, do these impacts differ between public and private transfers? Drawing on the National Income Dynamic Survey (NIDS), South Africa’s first nationally representative survey that follows more than 28,000 individuals over time, we found significant and positive impacts of the Older Person’s Grant and of remittances on the dietary diversity index, but not of the Child Support Grant. Moreover, we found no effect on food expenditure or on anthropometry (BMI) by the Older Person’s Grant, or remittances. However, some positive effects were found on children’s BMI from the Child Support Grant. We discuss why we observe different effects from different transfers, as well as giving several reasons why income transfers are failing to close the nutritional deficits in South Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Social protection is a set of instruments that aim to alleviate poverty and assist vulnerable people in managing risk (Barrientos 2013; World Bank 2012). Narrow approaches restrict the definition to public policy interventions, and frame social protection as a government responsibility towards citizens, who have a right to claim social assistance or social security from the state (ILO 2012). In this paper we favour a broader approach that includes private as well as public sources, following Brunori and O’Reilly (2010: 2): “social protection is generally described as the set of public and private mechanisms that protect and prevent individuals and households from suffering the worst consequences of shocks and stresses”. Specifically, we focus on publicly provided social grants (government-to-person (G2P) transfers) and on privately provided remittances (transfers within extended families).

In this paper, we examine and compare the impacts of social grants and remittances on one set of wellbeing outcomes, namely food security and nutrition, using South Africa as a case study. Food security is commonly understood as having access to sufficient food for a healthy, active life. It is a basic human need, and the right to food is enshrined in South Africa’s Constitution. Nutrition status, notably undernutrition, is an objective measure of food insecurity and hunger.

Although several studies have looked at whether social grants or remittances improve food security and/or nutritional outcomes, few of them have looked in the same study at a comprehensive set of indicators of food security and nutrition. Moreover, to date and to the knowledge of the authors, there is no evaluation that considers the effects of both social grants and remittances on nutrition and food security. There are several factors that differ across transfers and may influence whether public transfers are more effective than private ones (or vice versa) in reducing food insecurity, such as the frequency and regularity of the payments, the size of the transfers, and the use of the transfers (how transfers are spent). For example, public transfers tend to be regular and predictable but insensitive to variations in household needs over time, whereas private remittances might be more erratic but more responsive to occasional spikes in household needs for cash (such as an expensive health shock). Comparing public and private transfers can give us a better idea of the effectiveness of social protection programmes, as compared to private strategies such as sending informal transfers (remittances) to a family member living in a different location.

South Africa makes an excellent case study for several reasons: its history of internal migration and the fact that many families have relied and still rely on remittances; its comprehensive social protection system which has become more extensive post-Apartheid; and the fact that levels of malnutrition have remained high despite many poor households being recipients of social grants and/or remittances (Hendriks 2014; Devereux and Waidler 2017).

The paper is organised as follows: the next section reviews the literature on the impacts of social grants as well as of remittances on food security and nutrition, both in South Africa and in other countries. The paper continues with a description of the data and indicators used in our analysis, followed by the empirical strategy used to estimate the impacts of remittances and social grants on food security and nutrition. Afterwards, we present the descriptive statistics and the findings, before explaining and discussing the results and, finally, concluding.

2 Literature review

Public income transfers (social grants) and private income transfers (remittances) are both expected to improve the food security of recipients, through direct as well as indirect channels. The theory of change is that an increase in income will increase expenditure on food, which translates into increases in food intake and dietary diversity. This effect will be larger in poor households, who tend to allocate most of any incremental income to food purchases, because of ‘Engel’s law’ – poorer people spend higher proportions of their total income on food. Increased quantity and quality of food consumption should improve the nutritional status of transfer recipients directly. Indirectly, if some incremental income is allocated to health care this can also positively affect nutrition, because healthier people absorb and utilise nutrients more effectively (DFID 2011; Bailey and Hedlund 2012).

Several factors, however, will influence the extent to which social grants and remittances improve food security outcomes, as well as whether different transfers affect the outcomes differently. These factors include the frequency and regularity of the payments, the size of the transfers, and the use of the transfers (how transfers are spent) (Hagen-Zanker and Himmelstine 2015). One may expect that the greater the size of the transfer, the greater the poverty reduction effect – or, for our purposes, the greater the improvement in food security. Moreover, regular and predictable transfers are expected to lead to better outcomes, as compared to infrequent or irregular payments (Daidone et al. 2015). While social grants are usually regular and predictable, the frequency of remittances depends highly on the economic situation of the sender. When remittances come mainly from poor households, “family members may not be in a position to provide assistance at the time it is required and payments may not always be received on time” (Thomson and Posel 2002).

Regarding the use of the transfers, different transfers may be spent differently, and this will ultimately affect their poverty reduction impact (or, in this case, food security). How recipients use the transfer can depend on the purposes of sending the transfers (or the aim of the social protection programme in place); who is the intended beneficiary of the transfer (i.e. if the transfer targets children or other family members); and on who is the recipient of the transfer (e.g. women compared to men). For example, a few studies have shown that transfers received by women tend to have a higher impact on poverty reduction as they have a greater propensity to be spent on basic needs such as food (Duflo 2003). These factors (size of the transfer, regularity, sex of recipient, and intended use of the transfer) are context-specific, given that the characteristics of social protection transfers and remittances depend on the country studied.

The fact that most social protection is provided by family, community, and other informal sources has been acknowledged by researchers and institutions such as the World Bank and its Social Risk Management framework. Consequently, formal social protection should be designed in a way that complements informal strategies, or crowds out others for good reasons (Shepherd et al. 2004). Comparing the effects of remittances and social grants on well-being outcomes such as food security is necessary to inform policy making on the effectiveness of different sources of social protection.

2.1 Effects of social grants on food security

Numerous evaluations of public cash transfer programmes (CTPs) analyse their impact on self-reported food security indicators, while a smaller number of studies measure their impact on nutritional status (see Manley et al. 2012; Bastagli et al. 2016), usually of children in grant receiving households.

There is widespread evidence that cash transfers increase access to food and food consumption, and reduce food insecurity. A review of the impacts of conditional cash transfers on household food security in Mexico and Nicaragua found significant increases in per capita caloric availability, diet quality (consumption of vegetables, fruit and animal products) and dietary diversity (Hoddinott and Wiesmann 2010).Footnote 1 An evaluation of the Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP) in Ethiopia found that food insecure households which received free cash or food transfers as unconditional ‘direct support’ for at least two years improved their food security – measured by the number of months the household self-reported that it could meet its food needs (0.4 months a year). This effect was greater for households receiving larger transfers, reaching 2.5 months in some cases (Berhane et al. 2011: 82).

Empirical evidence on nutritional impacts is more limited, more variable and more ambiguous than data on self-reported food security indicators. The Mchinji Social Cash Transfer Scheme in Malawi recorded a substantial fall in the proportion of children with stunted growth, from 55% to 46% in just one year, while the prevalence of stunting in control group households remained unchanged – a significant attributable impact (Miller et al. 2011). On the other hand, a randomised controlled trial in Zambia found that households receiving regular cash transfers from the Child Grant Programme increased their food expenditure, food consumption (meals per day) and dietary diversity, relative to a control group, but these positive food security impacts did not translate into improvements in children’s nutritional status for the full sample. However, stunting was significantly reduced for children with educated mothers and for children with access to clean water (Seidenfeld et al. 2014: 41).

A systematic review covering 15 cash transfer programmes in 10 countries found no consistent relationship between receiving cash transfers and child nutritional status. “Half of the programmes showed positive effects and half negative effects on weight for age, and the same is roughly true for weight for height z-scores” (Manley et al. 2012: 43).Footnote 2 Interestingly, that review found no difference in nutritional outcomes between conditional and unconditional cash transfers, no effect of larger payment sizes, and a positive but statistically insignificant effect of longer programme duration. The authors conclude by noting that: “almost every programme was associated with increased food consumption and/or food diversity, a positive development. However, we see no effects on nutritional status. Clearly improved access to food alone is not sufficient to improve nutritional status” (Manley et al. 2012: 65). A more recent systematic review found that seven of 12 studies recorded a statistically significant increase in dietary diversity, and five of 13 studies found statistically significant reductions in child stunting (an indicator of long-term deprivation), but only one study of five and one study of eight found reductions in child wasting (an indicator of short-term hunger) and underweight, respectively (Bastagli et al. 2016). This is interesting as it suggests that regular cash transfers can reverse the effects of long-term nutritional deficits.

Recently, holistic package approaches that deliver cash transfers together with other forms of support, such as health insurance, access to microfinance and behaviour change communication (BCC) – have demonstrated more powerful impacts than cash transfers alone (Roelen et al. 2017). One pilot project in Bangladesh found that a combination of ‘cash + BCC’, where cash was complemented by nutrition training, performed significantly better than when cash only, food only, cash + food or food + BCC was delivered. In households that received cash+BCC, child stunting rates fell by 7.3 percentage points, but no other modality registered a significant impact on child undernutrition (Ahmed et al. 2016: 158).

2.2 Effects of remittances on food security

Studies looking at the effects of remittances on food security focus mainly on nutritional outcomes, especially of children, and the evidence so far is inconclusive as studies found positive, negative, as well as no effects of remittances on nutrition. Looking at international remittances (sent by migrants living abroad) and nutritional outcomes in Ecuador, Antón (2010) found a positive impact on short-term and medium-term child nutritional outcomes, but no significant impact of remittances on long-run anthropometric indicators. On the other hand, Ponce et al. (2011) – also in Ecuador and using a different instrumental variable technique – found no effect of remittances on nutrition. In Guatemala, Davis and Brazil (2016) showed that international remittances have no influence on the nutritional status of children left behind (aged 3 or less), which could indicate that fathers are not able to improve their economic situation soon enough to make an impact on their children’s nutrition. Finally, a panel study in Mexico showed that migration (including remittances) had a detrimental effect on children’s height-for-age (Nobles 2007).

Outside Latin America, Babatunde and Martinetti (2011) found that remittance income contributed to improved calorie supply at the household level in Nigeria, but had no significant impact on diet quality, micronutrient supply, and child nutritional status, while a recent study in Tanzania using an instrumental variable approach (Isotto and Kraybill 2017) showed that remittances increased the intake of nutrients such as proteins, vitamin A, vitamin C and calcium. In Ethiopia, Abadi et al. (2013) found that migration and remittances improved food security by allowing households to consume better quality and greater quantities of food, as well as a reduction in the frequency and severity of harmful coping strategies, such as reducing the quantity or quality of food consumed. In China, however, De Brauw and Mu (2010) find no significant association between internal migration and the prevalence of underweight in children.

From a review of these studies we conclude that remittances, such as social grants, are likely to improve food security (in terms of food consumption and the quality of food consumed). However, the impact of remittances on nutrition – which is a measure of long-term well-being – is more inconclusive than the impact on food security, as positive effects of remittances on nutrition are not always observed. Moreover, the discussion on internal remittances remains “virtually non-existent” (McKay and Deshingkar 2014: 5), with the exception of some studies which have shown that internal remittances usually flow to a large number of poor and rural households (Castaldo et al. 2012) and have the potential of reducing poverty and building human capital (Adams 2005; Lokshin et al. 2010; Taylor et al. 2005). Studies on internal remittances in middle income countries have shown that, while international remittances are more effective in decreasing poverty, internal remittances have a more equalising effect as they are better targeted at poor households (Taylor et al. 2005). The reason for this is that costs of international migration are higher, and therefore international migrants do not originate from the poorest households, whereas internal migration is often more concentrated among poor families.

2.3 Comparing the effects of social grants and remittances

To date and to the knowledge of the authors, there are no empirical studies that compare the effects of remittances and social grants on food security (including nutrition). There are, however, a few studies that look at the effects of social grants and remittances on other well-being indicators, such as health, income poverty and education. Hagen-Zanker and Himmelstine (2015) summarises these studies, and conclude that in most of them both types of transfers have a positive impact on household wellbeing. When looking at the magnitude of the impact, however, remittances appear to have a larger poverty reduction effect, most likely due to a higher level of the transfer and the fact that in these specific case studies remittances are better targeted at poor households. In addition, Waidler et al. (2016) compared the effects of remittances and social grants on expenditure patterns in Moldova and concluded that public and private transfers were not spent in the same way.

2.4 Social grants and remittances in South Africa

2.4.1 Social Grants

South Africa’s Department of Social Development (DSD) administers seven social grants, which target poor individuals from vulnerable demographic groups. The largest is the Child Support Grant (11.9 million beneficiaries), followed by the Older Person’s Grant (3.2 million) and the Disability Grant (1.7 million).

The Child Support Grant (CSG) is a monthly cash transfer for poor children up to 18 years old. Between the years 2008 and 2012, eligibility for the CSG was extended from 14 years old in 2008, to 16 years old in 2010 and to 18 years old in 2012. The CSG is means tested against household income, with an eligibility threshold that is double that of single personsfor married spouses. Because poverty is widespread it reaches two-thirds of all children in South Africa. The CSG is received by the child’s primary care-giver, who must be a South African citizen, permanent resident or refugee. Children aged 7–18 years are required to attend school as a condition for receiving the CSG, but this is not enforced. The amount paid by the CSG as of 2018 is R400 per month (±€25) (SASSA 2018).

The Older Persons Grant (OPG), also known as the Old Age Grant, is means tested and currently reaches more than 3 million pensioners. It can be claimed by any citizen, permanent resident or refugee who is resident in South Africa, is aged 60 years or older, and whose income plus assets fall below poverty thresholds that are adjusted periodically. The value of the OPG as of 2018 is R1,700 per month (±€100) (SASSA 2018).

There is evidence from several household surveys and impact evaluations that the nutrition status of children in households receiving social grants has improved. A 1999 survey found that children living with Old Age Grant (OAG) recipients were significantly taller, by approximately one standard deviation in height-for-age (Case 2001). Analysis of a 1993 survey found an increase in height-for-age z-scores (HAZ) of 1.16 standard deviations for girls living with a female OAG recipient (usually the child’s grandmother), but a much smaller increase for boys, and no significant impact on HAZ for either boys or girls living with a male OAG recipient (Duflo 2003).Footnote 3

An analysis of a subnational panel dataset, the KwaZulu-Natal Income Dynamics Study (KIDS), found a significant positive impact of the CSG on child stunting. Boys who started receiving the CSG in their first year gained 0.40 in HAZ by three years of age, compared to boys in the control group (Agüero et al. 2007). An impact evaluation of the CSG conducted in 2011 found no impact of the CSG on stunting across the full sample. “However, it improves anthropometric measures for two sub-samples, girls and children whose mothers have eight or more grades of schooling” (DSD, SASSA and UNICEF 2012).

Finally, an analysis of the first wave of NIDS panel dataset by Coetzee (2013) found a significant but small impact of the Child Support Grant on child HAZ, amounting to just 0.04 of a standard deviation. “These effect sizes are much smaller than expected, given the relative size of the transfer in relation to the mean per capita household expenditure of households in the sample” (Coetzee 2013: 429).

These empirical findings suggest that the positive nutritional impacts on children of the Old Age Grant, which is intended to be spent on the basic needs of older persons, are consistently larger than the impacts of the Child Support Grant, which is ‘labelled’ as a transfer intended for children. One factor might be the fact that the OAG pays substantially more than the CSG, and large numbers of older persons in South Africa are caring for grandchildren, either orphaned or living with them while the child’s parents are working or looking for work elsewhere – so the OAG becomes a main source of income and food security for both older persons and children.

2.4.2 Remittances

The most common form of human mobility in South Africa has been rural to urban migration (Crush et al. 2005), as rural areas are characterised by high levels of poverty and limited economic activity. During apartheid, movements of labour were mainly temporary, due to the fact that the permanent settlement of migrants was highly restricted (Posel 2001). Following the democratic transition in 1994, this trend was not altered as expected, and migration remains cyclical, although the proportion of female temporary migrants has increased (Collinson 2010). Rural poverty in South Africa remains high at around 70% (Stats SA 2014) and, due to the fact that productive land has been highly concentrated among the white population, poor households in South Africa continue to rely on remittances to cover their daily needs (Posel and Casale 2006). Nevertheless, analysing the National Income Dynamics Survey of 2008, Posel (2009) points out that many labour migrants were settling in destination areas to which they moved and that ties between migrants and households of origin were weakening. This translates into a sharp decline in the number of households receiving remittances compared to statistics derived from previous household surveys.

There are no studies – to the knowledge of the authors – looking at the effects of remittances on nutrition or food security in South Africa. There are some studies, however, that analyse the effects of remittances on poverty in post-apartheid South Africa.Footnote 4 Woolard and Klasen (2004) found in a study covering the years 1993 to 1998 that remittances were associated with a decrease in poverty in KwaZulu-Natal, while Maitra and Ray (2003) showed that remittances had a significant positive impact on the share spent on food. According to Collinson (2010), in South Africa there is a household selection effect, whereby better-off households are more likely to send migrants since they have more resources and better connections. After controlling for selection, the author showed that temporary migration improved the socio-economic status of the households, mainly through remittances.

In households where remittances decrease poverty and expenditure on food increases, food security indicators are expected to improve.

3 Data and indicators

For this analysis we used the National Income Dynamic Survey (NIDS), South Africa’s first nationally representative panel survey that follows more than 28,000 individuals over time. The first round was conducted in 2008 and subsequent rounds were carried out in 2010, 2012 and 2014. NIDS captures data on the livelihoods of individuals and households and therefore collects information on a range of socio-economic variables, such as income, employment, expenditure, migration, shocks, education and health. In this study we used only rounds 1 and 2, as some of the indicators used in our analysis had a large number of missing values in round 3, and round 4 was not available at the time of the study. Data also suffer from attrition due to non-response and refusal. To account for household- and individual-level attrition we used post-stratification calibrated weights when reporting cross-section analysis and panel weights when reporting on the balanced panel.

Income data in NIDS was collected individually by asking every adult from the household the amount they received per month from each income source (such as wage income, bonus payments, income from self-employment, also social grants and remittances). In the case of child grants (such as the Child Support Grant), adults were asked whether they received the specific grant on behalf of a child. Remittances are defined in the NIDS survey as all contributions from non-resident members as well as non-household members. We define all income variables in per capita terms. Finally, income and expenditure variables were deflated to 2008 as the base period. Deflators were computed from CPI data taken from the South African statistical office (Stats SA).

Our outcome variables consist of three indicators of food security: total expenditure on food, dietary diversity, and body mass index. All three indicators are objective, as subjective indicators were only available for the first round.

3.1 Dietary diversity index

Dietary diversity is considered one of the best performing measures of food security (Hoddinott and Yohannes 2002) and nutritional adequacy, including in South Africa (Steyn et al. 2006). The Household Dietary Diversity Score indicator guide identifies twelve food groups based on the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation’s Food Composition Table for Use in Africa (Ryan and Leibbrandt 2015).Footnote 5 Following this reasoning, the food items listed in the NIDS dataset were grouped into 12 food groups, based on the FAO’s table: cereals; white tubers and roots; vegetables; fruits; meat; eggs; fish and other seafood; legumes, nuts and seeds; milk and milk products; oils and fats; sweets; spices, condiments and beverages.

Detailed data on expenditure was collected at the household level by asking the amount of money the household spent in the last month on each particular food item (as well as whether the household has consumed it or not). The period of food consumption in NIDS was the previous 30 days. While an increase in the number of food categories consumed gives a good indication of improved food access and food security, there is no established threshold of the number of categories a household needs to consume to be defined as “food secure”. While the HDDS guide suggests taking the average diversity of the upper tercile, we follow Ryan and Leibbrandt (2015) using the same dataset and take average dietary diversity as a cut-off point (so that households below the average are considered food insecure). The main reason for this is that the average dietary diversity index (DDI) score is as high as 9 in NIDS, probably due to the long recall period for consumption (which is one month, compared to the 24 h recall period recommended by the HDDS guide).

3.2 Food expenditure

Food expenditure is a common indicator of food security. The rationale is that households that spend a high proportion of their total expenditure on food are more vulnerable than households that spend a lower proportion (Maxwell et al. 1999; Johnson and Toole 1991). This is because households that spend a large share of their income on food are more vulnerable to changes in food prices, as well as to changes in income.

Despite the fact that food expenditure does not perfectly capture the quality or quantity of food consumed (as this depends on availability and prices, and it also does not capture food produced for own consumption), food expenditure is still a useful measure to add to the analysis. The variable is defined as the household share of monthly food expenditure out of total expenditure. As suggested by Maxwell et al. (1999), a high food expenditure proportion is regarded as 60% and above, and these households are classified as food insecure. In this case we only analyse the binary variable as the continuous one is difficult to interpret.

3.3 Anthropometrics

We calculated the BMI for children aged 6 to 14 years, as well as for adults (above 14 years old). We analysed these two samples separately, as the BMI of adults is more likely to remain relatively constant over time. BMI is calculated as weight divided by height squared and it is derived from the anthropometric data collected in the adult and child individual surveys. Children who have a BMI more than 2 standard deviations below the median BMI for the reference group are classified as undernourished (Dinsdale et al. 2011). The classification of adults is less complex, with one threshold applied to all individuals over the age of 14. A BMI below 18.5 is identified as underweight and a BMI above 24.9 is identified as overweight.

Although anthropometric data was available for children under 5 and we were able to create the indicators for stunted and wasted (based on the z-scores for height-for-age and weight-for-height respectively), in the second round of the survey many children had missing values for these variables and therefore it was not possible to analyse nutrition with panel estimators for this age group.

4 Empirical strategy

We took advantage of the longitudinal nature of the data and estimated the relationship between transfers and food security via fixed effects regression. We also performed random effects and Mundlak estimates for robustness, given that some variables do not change considerably over time. The Hausman test, however, always recommends the use of fixed effects regressions. In the case of the dietary diversity index, we estimated random effects ordered probit regression (in addition to the linear fixed effects regression) as it is an interval variable and can only take 12 values, from 1 to 12.

Fixed effects regressions allow us to remove unobserved time invariant heterogeneity, which is very likely to be present in this study. Personal or household characteristics that are unobserved, like for example eating habits, are likely to affect food security outcomes and at the same time be correlated with the independent variables, therefore causing estimate bias. However, as it seems plausible to assume these variables stay constant over time, we can remove this bias by introducing individual fixed effects. The model can be expressed as follows:

where FS are the different food security outcome indicators. The coefficients of interest are the CSG, OPG, and remittances which denote, respectively, per capita monthly income (in Rands) from the Child Support Grant, Older Person’s Grant and remittances. The HH term refers to various household characteristics that can change over time, such as number of adults and children living in the household, maximum level of education attained in the household, and whether the household is located in a rural, urban formal, or informal area.Footnote 6 Y denotes the year fixed effects (in this case 2008) and αi + ϵitrefers to the error term which in this case is divided into two terms: αiis the time invariant error (the individual fixed effect) and ϵitis the time variant error, which is assumed to be random and uncorrelated with the independent variables.

As we are not only interested in analysing how transfers affect the continuous outcomes (values of BMI and DDI), but also how transfers affect the probability of being food secure (being not underweight and not overweight in the case of adults, and having an above average DDI in the case of the whole household), we estimated fixed effects (conditional) logits to see how an increase in the Older Person’s Grant, remittances, and Child Support Grant changed the odds of being food secure.Footnote 7 In this case eq. (1) remains the same with the only difference that the dependent variable is replace by the binary measures of food security.

Given that both social transfers and remittances were not randomly assigned to recipients, the model could still suffer from endogeneity if there were omitted variables that were time variant and affected both the treatment and the outcome. For instance, if there were a shock that caused a change in food security outcomes and, at the same time, generated a response in the remitter or the government by increasing or decreasing transfers, our coefficients could be biased. In the absence of proper instruments for all three transfers, we performed the estimates separately for different population groups to test for heterogeneity in effects. We re-estimated the model (1), restricting the sample to the African population in order to compare public and private transfer within a more homogenous group; and (2) restricting the sample to households that received social transfers (and that could or could not receive remittances).

As an additional robustness check and to better correct for potential endogeneity, we implemented some standard tools of policy evaluation and looked at the effects of the Child Support Grant and the Older Person’s Grant separately. The reason why we could not analyse both transfers in the same model is that, in order to implement quasi-experimental techniques such as propensity score matching or instrumental variable estimate (in cases where an instrument was available), we could only analyse one treatment at a time. In the case of remittances, it was not possible to find a valid instrument or variables that were good predictors of recipient status. As a result and given that we could not estimate causal impacts, we will only talk about associations when discussing the relationship between remittances and the different food security outcomes.

5 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows descriptive information on the percentage of households receiving the Older Person’s Grant (OPG), the Child Support Grant (CSG), and remittances – as well as combinations of these – and no transfers. Almost 50% of the South African population received either a poverty-related government transfer (CSG or OPG) or private transfers (remittances). The CSG was the transfer with the highest coverage, reaching more than 40% of households (30% of which did not receive either of the other two transfers). Of those households receiving the OPG, more than half also received the CSG, which is consistent with evidence of a high number of multi-generational households in South Africa and with elderly individuals pooling their income and living with children. The number of households relying only on remittances was low and has been decreasing over time (Posel and Casale 2006; Posel 2009), and this can be seen in Table 1 with only 1.8% of households receiving remittances in 2010 (compared with 5.7 in 2008).

In terms of the average amount received in recipient households, in 2008 remittances were much higher in magnitude than government transfers. However, remittances do not necessarily target poor families (this is consistent with the findings from Collinson (2010)), and the high average is mainly the result of high-income households receiving large amounts of remittances (see Fig. 1 below). It is also important to point out that in this survey remittances are defined as “any contribution from non-resident members or non-household members”, which means that not only transfers from migrants were included, but also other contributions such as child maintenance payments, payments to an elderly person living in other households or to a child studying in another city. The average amount received from the OPG more than doubled the amount received from the CSG: the value of the OPG was actually almost four times the value of the CSG, but there were many households with more than one child receiving the CSG.

When looking at the average per capita income before transfers, one can see that in the year 2008, households that relied on all three transfers were by far the poorest and households that only received remittances were the richest (in the latter case average income was similar to households receiving no transfers). In 2010 remittance recipient households were also the richest but those that received remittances and the OPG, or both the OPG and CSG and no remittances were slightly poorer that those receiving the three transfers. This could be due to the fact that those receiving all three transfers decreased by half in 2010 due to a large decrease in the number of households receiving remittances. It is curious to see that remittances reached both rich and poor households, but when they reached poor households they often complemented or were complemented by government transfers. One explanation could be that social transfers enable household members to go to the city and look for jobs in order to send money back home (Sienaert 2008; Ardington et al. 2009). Finally, the last row of Fig. 1 shows the percentage of income that each grant represents, on average, in recipient households. Households that received transfers were highly reliant on them, as generally more than 50% of per capita income comes from transfers, reaching 78% in households receiving all three transfers (the CSG, the OPG, and remittances).

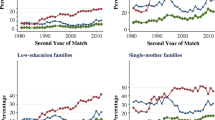

Figure 1 shows the distribution of (a) the CSG, (b) remittances, and (c) the OPG by expenditure decile. The CSG was relatively effective in targeting poor households. Households in the lower deciles of expenditure were more likely to receive greater amounts of the CSG. The lowest expenditure decile did not reflect this trend, which could be due to the fact that there were fewer children in this decile, or that very poor households did not apply for the grant due to lack of information or resources.Footnote 8 The opposite occured with remittances, as richer households received larger amounts on average. One explanation for this could be that richer households were in a better position to send remittances, but one could also speculate that there was a (positive) displacement effect, where remittances between poor people were crowded out by public transfers, as some qualitative evidence points out (Du Toit and Neves 2009).

The way transfers are targeted will determine their poverty reduction impact. As remittances have been decreasing in size, and a large proportion of them go to wealthier households, we do not expect to see a big impact of remittances on food security. At the same time, the amount of the CSG is too small to have a sizeable impact, even on basic needs. The OPG lies in between (Fig. 1c) – despite being weakly targeted, it is big enough to have an effect on food security. The drawback is that only households with elderly individuals benefit from this transfer.

In terms of frequency, social transfers were received monthly, whereas remittances were also received relatively frequently, with a median of 10 times per year in recipient households. Therefore, both private and public transfers were received regularly. However, remittances can decrease considerably during a crisis or with an idiosyncratic shock to the sender, therefore reducing the impact of their poverty reduction. Regarding the sex of the recipient, child grants were mainly received by women (97% in 2008 and 95% in 2010), whereas in the case of remittances the proportion of female recipients was lower but still very high (78 and 80% in 2008 and 2010, respectively). The decision on how money is spent may not only depend on who receives the transfer but also on who is the head of the household (which was self-defined in the survey). In this regard, 67.7% of remittance recipient households, 63.3% of CSG recipient households, and 67.5% of OPG recipient households were headed by a female. Given that there are no big differences between public and private transfer recipients in terms of who is the head of the household or who is the recipient of grants, we do not expect differences in impacts between public and private transfers to be driven by this factor.

Finally, the way households spend each specific grant and who benefits from them will depend on whether transfers are sent with a specific purpose and on the population group the transfer is targeting. The CSG is targeted at children and there is a clear message from the government that the grant is intended to improve children’s wellbeing, including nutrition and access to education. In the case of the OPG, even though the grant is targeted at elderly individuals, there is evidence that older persons usually live in households with children and pool their income to help all members of the household, particularly children (Case 2001; Lloyd-Sherlock 2012; Case and Menendez 2007). Consequently, we expect a positive effect of the CSG on children’s food security, and of the OPG on children as well as on adults’ food security (also due to the fact that the OPG is larger in size as compared to other transfers). In the case of remittances, we only expected to see improvements in food security in poor households, as richer ones were expected to be food secure. For poor households, remittances are a household level transfer, which is expected to be poverty reducing, as evidence from internal remittances points out (Castalso et al. 2012). However, the extent of the improvement will depend on how the money is distributed among household members, and whether transfers are big enough to cover basic needs.

Table 2 shows food security outcomes across the different transfer recipient groups. Results are generally consistent across groups, meaning that when we compare the different food security indicators the ranking holds: households that receive no transfers or only remittances are better off, followed by those receiving remittances and either the CSG or the OPG. This group is followed by households receiving only the OPG, only the CSG, both the OPG and the Child Support Grant and finally by households receiving all three grants, which are the most food insecure in terms of all indicators.

6 Results

For the econometric analysis, we looked at three continuous indicators of food security (dietary diversity and body mass index for adults and for children), and four binary indicators, expressed as the odds of being food secure in terms of dietary diversity (DDI higher than 8) and food expenditure (spending less than 60% of total expenditure on food); being not underweight (BMI > 18.5); and being not overweight (BMI < 24.9) (in both cases for adults older than 14 years old).Footnote 9 We did not estimate the regressions using the share of food expenditure as a continuous variable given that results were hard to interpret, as an increase in the share spent on food can be considered a positive outcome if the household is poor but richer households spend a lower share of their income on food. Table 3 shows the fixed effects results when the dietary diversity index was the dependent variable. While we did not see significant impacts of the Child Support Grant, the Older Person’s Grant was positive and significant in all specifications. Remittances were positively associated with the DDI; although coefficients were lower in magnitude compared to the OPG and coefficients were significant only at the 10% level. To have a clearer idea of the magnitude of the coefficients, we examined the results of the random effects ordered probit regressions (given that the dependent variable is ordinal), expressed as average marginal effects in Table 4. For this we have re-classified the DDI in 9 categories (from 4 to 12), as very few individuals had a DDI lower than 4. The regression shows that recipients of the Older Person’s Grant as well as remittances had higher probabilities of having a higher DDI. For instance, an increase in 100 Rands of both per capita remittances and OPG increased the probability of having a DDI of 12 by 1 percentage point.

There are several explanations for why we see a positive impact of the OPG but not of the CSG. In the first place, as mentioned earlier, the OPG is approximately four times the size of the CSG, so it is to be expected that this grant will have a larger impact on household food security. Another reason is that the DDI identifies well-being at a household level, and we expect a higher effect from the OPG given that this grant is usually pooled and benefits the whole household. In addition, as discussed in Devereux and Waidler (2017), there is evidence that the CSG is being “diluted” in terms of what it is spent on, as poor households have needs other than food as well as recipients of the transfer –caregivers of children, many of whom are teenagers- may be spending the grant on goods that do not benefit their children directly. Finally, remittance income is also a household level transfer, which is often spent on food, so these results are consistent with previous evidence from South Africa (Waidler 2016; Maitra and Ray 2003).

With regard to the effects of transfers on BMI (Tables 5 and 6) we observed no impacts of social protection transfers on nutrition. The OPG is significantly related to child BMI in some of the specifications, but coefficients are only significant at the 10% level and do not hold when estimating random effects and Mundlak models. Moreover, although the random effects models show a negative effect of the OPG on adult BMI, this significant effect disappeared when we estimated Mundlak regressions. This is likely caused by a negative selection into social protection transfers, where individuals with worse nutritional outcomes are more likely to receive transfers from the government. Once we accounted for this by removing the correlation between the error term and time invariant variables - through Mundlak or fixed effects models - coefficients were no longer significant. Remittances were not significantly associated with nutritional outcomes either. Our findings of no effect of transfers on BMI are in line with previous findings that there is no consistent positive relationship between grants and nutritional outcomes.

Finally, Table 7 shows the conditional logit expressed in odds ratios when food security indicators are expressed as binary variables. As with the fixed effects regression, we only see significant impacts in the case of DDI: an increase in one rand of per capita OPG increased the odds of being food secure by 0.10%. In this case, however, the coefficient for remittances was not statistically significant, while the Child Support Grant appeared to be associated with an increased probability of being food secure. The differences between these results and the previous ones can be explained by the fact that the number of observations significantly declined when estimating conditional logit estimations, as only those individuals who changed their status from 2008 to 2010 (e.g. from being food insecure to food secure or vice versa) were kept in the estimation. For this reason, these results should be interpreted with caution. We did not see significant effects when we analysed the odds of being neither overweight nor underweight, and food secure in terms of share of expenditure on food.

6.1 Endogeneity concerns: Additional estimates

Given that our data does not cover pre-program outcomes, and that selection into treatment (receiving remittances and social protection transfers) is not random, our study could still suffer from endogeneity bias due to omitted-time varying variables.Footnote 10 An even more problematic bias could be caused by reverse causality, which would arise if the level of food security and nutrition of individuals determine whether they receive remittances or social grants. As robustness tests, therefore, and based on data availability and characteristics of the transfers, we performed some additional standard methods of policy evaluation, namely propensity score matching and instrumental variable estimation. Given that we could not apply the same econometric technique to analyse all three transfers, we estimated the effects of each transfer separately. Another reason why we could not estimate them together is the fact that beneficiaries of remittances, OPG, and CSG have different characteristics, which means their corresponding control groups will also be different.

In the case of the Older Person’s Grant, we were able to instrument pension receipt with age eligibility, given that 80% of age eligible individuals in South Africa receive the pension.Footnote 11 This instrument has been used in other papers studying the impacts of this transfer (see, for example, Standish-White and Arden Finn (2015)). Results confirm our findings that pension income improves food security (the dietary diversity index), but has no effect on nutrition (Table 8). This holds when we analyse the continuous variable (amount received), as well as when estimating the effects of receiving or not receiving the grant (binary variable).

In the case of the Child Support Grant, we relied on matching techniques. In the absence of a good instrument, other studies such as Coetzee (2013) and DSD, SASSA and UNICEF (2012) have used this technique to estimate the effects of the CSG on different well-being indicators. To estimate the treatment, we used variables that influence the probability of an individual living in a grant recipient household, but were unlikely to be affected by the outcome, such as place of residence, race, housing conditions, and the number of age-eligible children in the household. All the estimates shown below satisfy the balancing property (meaning that differences in covariates between treated and control individuals are not significant after matching), as well as post-estimate tests, which indicated that the matching was done correctly.Footnote 12 We performed two different matching techniques: radius matching, and nearest neighbour matching based on the three closest neighbours.Footnote 13

Table 9 below shows the average treatment effects of the Child Support Grant on food security and nutrition. Again, we see that the Child Support Grant had no effect on food security (measured through the dietary diversity index), given that the t-statistic was less than 1.96 when performing both radius matching as well as nearest neighbour matching. The effects on adults’ BMI were also insignificant. However, when estimating the effects on BMI for children – and as opposed to the estimates shown in the previous sub-section – we observed positive effects from the CSG. Receiving the Child Support Grant lead, on average, to a 0.39 or 0.50 standard deviation increase in body mass index, depending on the matching technique used. The magnitude of this effect is quite considerable given the distribution of this variable (see Table 10).

Although results should be interpreted with caution given that we could not use baseline characteristics to estimate the probability of receiving the Child Support Grant,Footnote 14 and that propensity score matching only controls for selection on observables. However, the advantage of this technique is that it allows us to create a proper counterfactual of non-participants and to get an unbiased estimate of the effects of this programme, provided all assumptions hold. This may be the reason why findings differ with respect to our previous estimates, and why we now observe positive effects of the CSG. These positive effects on child nutrition are in line with previous evaluations of the Child Support Grant (see, for example, Coetzee (2013) and DSD, SASSA and UNICEF (2012)).

Even though some studies, including this one, have found positive effects of the Child Support Grant on specific nutritional indicators, a review of the literature indicates that the levels of malnutrition in South Africa have not declined, or are declining very slowly, as the proportion of stunted children in South Africa has fluctuated between 20% and 30% since the early 1990s (various sources, discussed in Devereux and Waidler 2017). The next section, therefore, discusses why we think this is the case.

With regard to remittances, it was not possible to find a good instrument or to implement propensity score matching, given that covariates that would be expected to influence the probability of receiving remittances did not turn out to be good predictors of treatment status. However, this also means that the estimation of the effects of remittances is less likely to suffer from endogeneity bias, as recipients and non-recipients do not differ, on average, on some of the main socio-demographic characteristics. One possible explanation for this is that remittances can be received from both household and non-household members, and therefore senders have different characteristics and send remittances for different purposes. In addition, not all remittances are sent by migrant household members, and this lowers the likelihood of reverse causality. Assuming that there is reverse causality, we would expect this endogeneity to lead to downward bias, given that migrants are more likely to be negatively selected in terms of income and education, which would imply that remittance recipient households are, in general, less food secure on average (Jacobs and du Plessis 2016). This would also imply that the effects of remittances found in this paper would be under-estimated.

Finally, another discussion point that was mentioned in the previous section is interactions between different types of transfers, given that some households receive only one, others two and others all three types. To explore whether, for instance, public transfers ‘crowd out’ private transfers, we estimated specifications that included only one resource inflow and subsequently added the others to see if the effect of the initial variable changed. With this exercise we can analyse if households that receive all three transfer types have different outcomes compared to those that only receive one, or conversely, if the effect of one transfer type disappears once the household receives others. These regressions are shown in Table 17 in the appendix. The effects of remittances, the Child Support Grant and the Older Person’s Grant did not change if analysed separately or together with the other transfers. This means that there is no sign of crowding out – receiving one additional transfer does not necessarily reduce the effect of the others.

7 Discussion: Why are social grants failing to improve nutrition outcomes in South Africa?

Empirical evidence points to a paradox in South Africa: self-reported indicators of food insecurity are falling, but indicators of malnutrition are not, or are falling much more slowly. In the 1990s, responses to the question “In the past year, was there ever a time when you could not afford to feed the children in the household?” in national annual household surveys displayed a steady decline (i.e. improvement), from 41% in 1994 to 31% in 1998 (Aliber 2009). In the 2000s, this positive trend continued. Responses in national annual household surveys to a slightly different question – “In the past 12 months, did any child in this household go hungry because there wasn’t enough food?” – registered a decline from 24% in 2002 to 11% in 2012 (Hendriks 2014).

Other sources broadly confirm this positive trend. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 2012 (SANHANES-1) reported that “the proportion of food insecure households halved from 1999 to 2008 (from 52.3% to 25.9%)” and that this “marked improvement” was maintained up to 2012 (HSRC 2013: 147). On the other hand, a report on poverty and inequality in South Africa found that the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (derived from the annual GHS surveys), deteriorated slightly between 2012 and 2015, suggesting “a modest increase in food insecurity since 2012” (World Bank 2018: 24). Conversely, a national community survey conducted by Statistics South Africa in 2016 found that 13.3% of households reported having skipped a meal during the previous 12 months – a positive decline from 16.7% in 2015 (Stats SA 2016: 87–88).

However, these self-reported indicators were not confirmed when children’s nutrition status was measured anthropometrically. The proportion of stunted children in South Africa has fluctuated between 20% and 30% since the early 1990s. The highest rate of 28.0% was recorded in 2003 and the lowest rate of 20.9% was recorded in 2012, but stunting rates were almost identical in 1993 and 2008, at 24.5% and 24.6% respectively, and the second lowest rate of 21.6% was recorded in 1999 (various sources, discussed in Devereux and Waidler 2017).Footnote 15

Both sets of indicators pre-date the introduction of the Child Support Grant in 1998 and both reveal no clear association between social grants and either food security or nutrition outcomes. Self-reported food security was already improving for children before the CSG was introduced, and children’s nutrition status has not improved significantly since then. This is surprising for two reasons. Firstly, the number of poor and food insecure children reached by the CSG has increased dramatically since 1998, from just 34,000 children under 7 years old in 1998 to more than 11 million children up to 18 years of age in 2013 (Beukes et al. 2015). In 2012, social grants made the single largest contribution to income in poor households (42%), more than wages (32%) (Stats SA 2012).

There are several reasons why social grants are failing to reduce malnutrition significantly in South Africa (discussed in more detail in Devereux and Waidler (2017)). First, although social grants in South Africa are relatively generous in comparison with cash transfer programmes in other countries, they are not sufficient to meet nutritional needs, as food prices are rising and social grants are not index-linked (e.g. the annual increment of the Child Support Grant is typically a modest R10 or R20, irrespective of inflation rates). Two other important reasons are dilution among other individuals and other cash needs, and deductions made by service providers, sometimes illegally. Regarding the former, social grants targeted at individuals rather than households face being ‘diluted’ in two ways: firstly, in terms of who they are spent on, and secondly in terms of what they are spent on. Both forms of dilution can reduce the impacts on the intended beneficiaries. A qualitative evaluation of the CSG confirmed that the CSG cash is used for a diverse range of food and non-food needs by recipients (DSD, SASSA and UNICEF 2011). In terms of the latter, the Department of Social Development (DSD) introduced a payment system for social grants that uses bank accounts and SASSA payment cards – rather than manual disbursement of cash transfers – for several reasons, including: to reduce leakages due to fraud and corruption, and to facilitate financial inclusion of the poor and to reduce their vulnerability to exploitative money-lenders. However, giving bank accounts to beneficiaries also gave opportunities to a range of service providers to make unauthorised deductions from these bank accounts, such as for airtime by cellphone companies and for funeral policies by insurance companies (DSD 2016). Finally, nutrition requires more than food. UNICEF’s conceptual framework for the determinants of child malnutrition (UNICEF 1990) identified three ‘underlying causes’ of child malnutrition: inadequate access to food, inadequate care for children and women, and insufficient health services and unhealthy environment. Only the first of these can be directly attributed to poverty – not enough resources at the individual or household level to acquire adequate food.

8 Conclusion

Large numbers of South Africans receive social grants (public transfers) or remittances (private transfers), yet the levels of food insecurity – particularly in terms of nutritional outcomes – are surprisingly high. In this paper we have attempted to estimate the effects of (or associations among) both social grants and remittances on (and) food security and nutrition, as well as to see whether impacts differ among these three transfers (the Child Support Grant, the Older Person’s Grant and remittances). While several studies have attempted to estimate the relationship between one of these transfers on nutrition or food security, there is no study comparing all three transfers.

In this paper we found a significant and positive effect of the Older Person’s Grant on the dietary diversity index (DDI), but not of the Child Support Grant. The differences in impacts between the CSG and the OPG correspond to differences in the size of the transfers, as well as to the fact that the CSG may be spent not only on children and on needs other than food. Remittances also improved the DDI (although to a lower extent), which is in line with other findings that remittances in South Africa are spent on food (especially when they are received by poor households).

We found no significant effects of either the Child Support Grant, the Older Person’s Grant or remittances on total household expenditure on food. As noted above, this is an ambiguous indicator because households can afford to spend more on food as their income rises, but because spending on food is relatively income-inelastic, households with rising incomes allocate steadily declining proportions of their total expenditure to food.

Regarding nutrition, we found no effect on anthropometry (BMI) by OPG or remittances, which supports other findings – both from South Africa as well as from other countries – that grants and remittances do not have a consistent positive impact on nutrition. On the other hand, however, some estimates point towards a positive effect of the CSG on children’s BMI. This is in line with previous studies in South Africa, which have found positive nutritional outcomes of the Child Support Grant. One reason why we only observed positive impacts from this transfer could be the fact that the grant is targeted at children and there is a clear message from the government that the money should improve children’s nutritional outcomes.

In absence of randomisation in the selection of social grants or remittance recipients, as well as in the absence of baseline data collected before the first migration episode or before the launch of the social protection programmes, this paper relies on quasi-experimental techniques of policy evaluation to deal with endogeneity. Moreover, instruments were not available for some of the transfers, and therefore we should be cautious in claiming causality. Another feature that has posed methodological challenges is the small overlap between social grants and remittance beneficiaries. Comparing the effects of remittances and social assistance in the same estimation when groups of recipients are highly heterogeneous can be problematic. However, this is a finding per se, as it indicates that remittances and social transfers reach different population groups.

Being aware of the importance of different strategies households rely upon to improve their well-being is important and can inform policy making in different ways. The case study of South Africa shows that different factors, such as whether transfers are targeted to a specific individual or at entire households, the size of the transfers, and the motivations for sending these transfers, influence the impact that remittances and social grants have on food security. Moroever, and despite in South Africa social protection transfers have significantly higher coverage than remittances (and, therefore, they are more likely to contribute to poverty reduction), transfers reach different population groups, which means different households rely on different social protection strategies. Moreover, in some cases, public and private transfers complement each other, as very poor households are likely to receive both social grants and remittances.

There are many lessons that the governments of South Africa and other countries can draw from these findings. Firstly, food security and nutrition security are not the same. Improvements in food security can be recorded with no concomitant improvement in nutrition status, so both sets of indicators must be monitored and specific interventions must be designed and delivered to tackle each. Secondly, it is unrealistic to expect poor and food insecure people to rely on informal support from others, rather than on formal social assistance from the state. It is clear, for instance, that remittances are accessed only by certain households, are unpredictable in terms of their frequency and value and, crucially, are not necessarily pro-poor since they require labour mobility. Conversely, well-designed social grants are characterised by their predictability (regular delivery and fixed payments) and they usually aim to reach the poorest and most food insecure.

Thirdly, the most direct way to maximise the impact of social grants is to increase payment amounts, given the evidence that grants targeted at individuals are also spent on other household members and for multiple purposes other than food. Fourthly, however, income transfers increase access to food but not necessarily nutrition outcomes. Holistic approaches to tackling malnutrition are needed that address food as well as non-food determinants, such as access to health care, sanitation facilities and potable water. Education campaigns on the importance of dietary diversity, hygienic practices and exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months are equally important. Such campaigns have been found to be most effective when provided as ‘BCC’ messaging along with cash transfers – so-called ‘cash plus’ interventions (Roelen et al. 2017).

Finally, following from this insight, perhaps the most important lesson is that solutions to social policy problems need to be problem-focused, not intervention-driven. Countries across the world that have succeeded in dramatically reducing malnutrition have done so by setting this as a goal (cf. Brazil’s ‘Zero Hunger’ initiative), and then done whatever is needed to achieve this, across several sectors – health, education, agriculture, social protection (see Gillespie et al. 2016). This approach has proved more effective than selecting one policy instrument, such as cash transfers, and expecting it to solve food insecurity and malnutrition on its own.

Notes

Unconditional transfers – as opposed to conditional cash transfers – are not conditional upon certain behaviors, such as school attendance or regular medical check-ups.

Stunting, measured by height-for-age z-scores (HAZ), is an indicator of long-term or chronic undernutrition. A child has stunted growth if her or his height is more than 2 standard deviations below the height of a child the same age in a reference population. Wasting, measured by weight-for-height z-scores (WHZ), is an indicator of short-term weight loss and hunger.

The Old Age Grant has subsequently been renamed the Older Person’s Grant.

Due to lack of a nationally representative survey that can explore trends in migration, studies on migration and remittances in South Africa are limited.

For more information on the food composition table, see: www.fao.org/docrep/003/X6877E00.htm.

Due to the fact that NIDS follows individuals and not households, some individuals could move to another households (and therefore change location) from one wave to the other.

We could not look at BMI for children (probability of being nourished) as there were not enough individuals who changed their outcome (from being under-nourished to nourished or vice versa) from one year to the other.

Very poor households may be discouraged to apply if they lack the necessary documents or have to travel far away to apply for the grant, or as a result of less motivated caregivers.

We could not estimate conditional logits for child BMI (probability of being nourished) as the sample was very small (very few individuals had changed from being nourished to unnourished and vice versa.

Although in the previous section we performed sub-sample analysis, trying to overcome this limitation, restricting the sample to specific groups threatens the external validity of the study.

Individuals (both men and women) who are 60 years old or above can qualify for the grant.

The regression to estimate the propensity score as well as the post-estimate tests are shown in the appendix.

Nearest neighbour matches a treated participant with its closest non-treated participant (or, in our case, with the 3 closest non-participants), whereas radius matching combines nearest neighbour matching with caliper matching. Caliper matching imposes a restriction of a maximum permitted distance between the neighbours (avoiding in this way matching participants whose absolute propensity score difference is high).

For the propensity score matching assumptions to be satisfied, potential outcomes should be independent of treatment assignment. Therefore, in an ideal case, we would use baseline characteristics of individuals (which pre-date the start of the programme), to estimate the probability of receiving the grant.

These figures are not directly comparable, as different sampling frames and age cohorts were used.

References

Abadi, N., Techane, A., Tesfay, G., Maxwell, D., and Vaitla, B. (2013). The impact of remittances on household food security: A micro perspective from Tigray, Ethiopia. Preliminary draft.

Adams, R. H. (2005). Remittances, household expenditure and investment in Guatemala. Policy research working paper, No. 3532. Washington DC: World Bank.

Agüero, J., Carter, M. and Woolard, I. (2007). The impact of unconditional cash transfers on nutrition: the South African Child Support Grant, IPC Working Paper, no. 39. Brasilia: International Poverty Centre.

Ahmed, A., Hoddinott, J., Roy, S., Sraboni, E., Quabili, W. and Margolies, A. (2016). Which kinds of social safety net transfers work best for the ultra poor in Bangladesh? Operation and impacts of the Transfer Modality Research Initiative. Dhaka: IFPRI and World Food Programme.

Aliber, M. (2009). Exploring statistics South Africa’s national household surveys as sources of information about household-level food security. Agrekon, 48(4), 384–409.

Antón, J. I. (2010). The impact of remittances on nutritional status of children in Ecuador. International Migration Review, 44(2), 269–299.

Ardington, C., Case, A., & Hosegood, V. (2009). Labor supply responses to large social transfers: Longitudinal evidence from South Africa. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(1), 22–48.

Babatunde, R. O. and Martinetti, E. C. (2011). Impact of migrant remittances on food security and nutrition of farming households in Kwara State, Nigeria. Contributed paper for the conference “Shocks in Developing Countries” in Paris, France.

Bailey, S., & Hedlund, K. (2012). The impact of cash transfers on nutrition in emergency and transitional contexts: A review of evidence. London: Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

Barrientos, A. (2013). Social assistance in developing countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bastagli, F., Hagen-Zanker, J., Harman, L., Barca, V., Sturge, G., & Schmidt, T. (2016). Cash transfers: What does the evidence say? A rigorous review of programme impact and of the role of design and implementation features. London: Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

Berhane, G., Hoddinott, J., Kumar, N., & Taffesse, A. (2011). The impact of Ethiopia’s productive safety nets and household asset building Programme: 2006–2010. Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Beukes, R., Jansen, A., Moses, M. and Yu, D. (2015). Exploring the eligibility criteria of the child support Grant and its impact on poverty. Paper presented at the 2015 biennial conference of the economic Society of South Africa. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. 2–4 September.

Brunori, P. and O’Reilly, M. (2010). Social protection for development: A review of definitions. Paper prepared in the framework of the European Report on Development 2010. Brussels: European Commission.

Case, A. (2001). Does money protect health status? Evidence from south African pensions, NBER working paper, no. 8495. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Case, A., & Menendez, A. (2007). Does money empower the elderly? Evidence from the Agincourt Demographic Surveillance Site, South Africa. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 69, 157–164.

Castaldo, A., Deshingkar, P., & McKay, A. (2012). Internal migration, remittances and poverty: evidence from Ghana and India. Migrating out of poverty working paper (p. 7). Brighton: University of Sussex.

Coetzee, M. (2013). Finding the benefits. Estimating the impacts of the south African child support Grant. South African Journal of Economics, 81(3), 427–450.

Collinson, M. (2010). Striving against diversity: The dynamics of migration, health, and poverty in rural South Africa. Global Health Action, 3, 5080.

Crush, J., William, V., and Peberdy, S. (2005). Migration in southern Africa. Global Commission on International Migration.

Daidone, S., Pellerano, L., Handa, S., & Davis, B. (2015). Is graduation from social safety nets possible? Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. IDS Bulletin, 46(2), 93–102.

Davis, J., & Brazil, N. (2016). Migration, remittances, and nutrition outcomes of left-behind children: A national level quantitative assessment of Guatemala. PLoS One, 11(3), e0152089.

De Brauw, A., & Mu, R. (2010). Migration and the overweight and underweight status of children in rural China. Food Policy, 36(1), 88–100.

Department for International Development (DFID). (2011). Cash transfers evidence paper. London: DFID.

Department of Social Development (DSD) (6 May 2016). Statement by the Minister of Social Development, Ms Bathabile Dlamini, on Unauthorised Grant Deductions. www.blacksash.org.za/index.php/media-and-publications/media-statements/1681 [accessed 14 July 2016].

Department of Social Development, South African Social Security Agency and UNICEF (DSD, SASSA and UNICEF). (2011). Child support Grant evaluation 2010: Qualitative research report. Pretoria: UNICEF South Africa.

Department of Social Development, South African Social Security Agency and UNICEF (DSD, SASSA and UNICEF). (2012). The south African child support Grant impact assessment: Evidence from a survey of children, adolescents, and their households. Pretoria: UNICEF South Africa.

Devereux, S. and Waidler, J. (2017). Why does malnutrition persist in South Africa despite social grants? Food Security SA Working Paper Series No.001.DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Food Security, South Africa.

Dinsdale, H., Ridler, C., & Ells, L. (2011). A simple guide to classifying body mass index in children. Oxford: National Obesity Observatory.

Du Toit, A., and Neves, D. (2009). Trading on a Grant: Integrating Formal and Informal Social Protection in Post-Apartheid Migrant Networks. Brooks World Poverty Institute. BWPI Working Paper 75.

Duflo, E. (2003). Grandmothers and granddaughters: Old-age pensions and intra-household allocation in South Africa. World Bank Economic Review, 17(1), 1–25.

Gillespie, S., Hodge, J., Yosef, S., & Pandya-Lorch, R. (Eds.). (2016). Nourishing millions: Stories of change in nutrition. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Hagen-Zanker, J., & Himmelstine, L. (2015). What is known about the differential impacts of cash transfers and remittances on poverty and vulnerability of households? Social Policy and Society, 14(2), 00–14.

Hendriks, S. (2014). Food security in South Africa: Status quo and policy imperatives. Agrekon, 53(2), 1–24.

Hoddinott, J., & Wiesmann, D. (2010). The impact of conditional cash transfer programs on food consumption, chapter 11 in Adato, M. and Hoddinott, J. (editors) conditional cash transfers in Latin America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hoddinott, J., & Yohannes, Y. (2002). Dietary diversity as a food security indicator. Washington DC: FANTA.

Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). (2013). South African National Health and nutrition examination survey (SANHANES-1). Cape Town: HSRC Press.

ILO. (2012). Text of the recommendation concerning National Floors of social protection. Geneva: International Labour Conference.

Jacobs, W., & Du Plessis, D. J. (2016). A spatial perspective of the patterns and characteristics of main-and substream migration to the Western cape, South Africa. Urban Forum, 27(2), 167–185.

Johnson, U. and Toole, D. (1991). Household food security and nutrition. A conceptual analysis. UNICEF, New York (mimeo).

Lloyd-Sherlock, P., Saboia, J., & Ramírez-Rodríguez, B. (2012). Cash transfers and the well-being of older people in Brazil. Development and Change, 43(5), 1049–1072.

Lokshin, M., Bontch-Osmolovski, M., & Glinskaya, E. (2010). Work-related migration and poverty reduction in Nepal. Review of Development Economics, 14(2), 323–332.

Maitra, P., & Ray, R. (2003). The effect of transfers on household expenditure patterns and poverty in South Africa. Journal of Development Economics, 71(1), 23–49.

Manley, J., Gitter, S., & Slavchevska, V. (2012). How effective are cash transfer programmes at improving nutritional status? A rapid evidence assessment of programmes’ effects on anthropometric outcomes. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

McKay, A., & Deshingkar, P. (2014). Internal remittances and poverty: further evidence from Africa and Asia. Migrating out of poverty working paper (p. 12). Brighton: University of Sussex.

Maxwell, D., Ahiadeke, C., Levin, C., Armar-Klemesu, M., Zakariah, S., & Lamptey, G. (1999). Alternative food security indicators: Revisiting the frequency and severity of coping strategies. Food Policy, 24(4), 411–429.

Miller, C., Tsoka, M., & Reichert, K. (2011). Impacts on children of cash transfers in Malawi, chapter 6 in Handa, S., Devereux, S and Webb, D. (editors). In Social protection for Africa’s children. London: Routledge.

Nobles, J. E. (2007). The effects of Mexican migration on sending families. ProQuest.

Ponce, J., Olivie, I., & Onofa, M. (2011). The role of international remittances in health outcomes in Ecuador: Prevention and response to shocks. International Migration Review, 45(3), 727–745.

Posel, D. (2009). Migration: Analysis of the NIDS wave 1 dataset. NIDS Discussion Paper, No. 1. Durban: School of Development Studies, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal.

Posel, D. R. (2001). Intra-family transfers and income pooling. South African Journal of Economics, 69(3), 501–528.