Abstract

Background

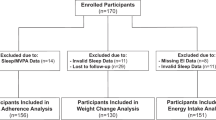

Self-efficacy, or the perceived capability to engage in a behavior, has been shown to play an important role in adhering to weight loss treatment. Given that adherence is extremely important for successful weight loss outcomes and that sleep and self-efficacy are modifiable factors in this relationship, we examined the association between sleep and self-efficacy for adhering to the daily plan. Investigators examined whether various dimensions of sleep were associated with self-efficacy for adhering to the daily recommended lifestyle plan among participants (N = 150) in a 12-month weight loss study.

Method

This study was a secondary analysis of data from a 12-month prospective observational study that included a standard behavioral weight loss intervention. Daily assessments at the beginning of day (BOD) of self-efficacy and the previous night’s sleep were collected in real-time using ecological momentary assessment.

Results

The analysis included 44,613 BOD assessments. On average, participants reported sleeping for 6.93 ± 1.28 h, reported 1.56 ± 3.54 awakenings, and gave low ratings for trouble sleeping (3.11 ± 2.58; 0: no trouble; 10: a lot of trouble) and mid-high ratings for sleep quality (6.45 ± 2.09; 0: poor; 10: excellent). Participants woke up feeling tired 41.7% of the time. Using linear mixed effects modeling, a better rating in each sleep dimension was associated with higher self-efficacy the following day (all p values < .001).

Conclusion

Our findings supported the hypothesis that better sleep would be associated with higher levels of reported self-efficacy for adhering to the healthy lifestyle plan.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(10):1755–67.

Zarzour A, Kim HW, Weintraub NL. Understanding obesity-related cardiovascular disease: it’s all about balance. Circulation. 2018;138(1):64–6.

Wilding JPH, Jacob S. Cardiovascular outcome trials in obesity: A review. Obesity reviews : An official J Int Assoc Stud of Obes. 2020.

Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Martin CB, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence by race and Hispanic origin-1999–2000 to 2017–2018. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020.

Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Sleep, circadian rhythm and body weight: parallel developments. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75(4):431–9.

Ford ES, Cunningham TJ, Croft JB. Trends in self-reported sleep duration among US adults from 1985 to 2012. Sleep. 2015;38(5):829–32.

Xiao Q, Arem H, Moore SC, Hollenbeck AR, Matthews CE. A large prospective investigation of sleep duration, weight change, and obesity in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(11):1600–10.

Patel SR, Malhotra A, White DP, Gottlieb DJ, Hu FB. Association between reduced sleep and weight gain in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(10):947–54.

Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Chaput JP. Associations among self-perceived work and life stress, trouble sleeping, physical activity, and body weight among Canadian adults. Prev Med. 2017;96:16–20.

Sa J, Samuel T, Chaput JP, Chung J, Grigsby-Toussaint DS, Lee J. Sex and racial/ethnic differences in sleep quality and its relationship with body weight status among US college students. J Am Coll Health. 2019:1–8.

Bandura A. The primacy of self-regulation in health promotion. Appl Psychol. 2005;54:245–54.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215.

Nezami BT, Lang W, Jakicic JM, et al. The effect of self-efficacy on behavior and weight in a behavioral weight-loss intervention. Health Psychol : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2016.

Warziski MT, Sereika SM, Styn MA, Music E, Burke LE. Changes in self-efficacy and dietary adherence: the impact on weight loss in the PREFER study. J Behav Med. 2008;31(1):81–92.

Goode R, Ye L, Zheng Y, Ma Q, Sereika SM, Burke LE. The impact of racial and socioeconomic disparities on binge eating and self-efficacy among adults in a behavioral weight loss trial. Health Soc Work. 2016;41(3):e60–7.

Choo J, Kang H. Predictors of initial weight loss among women with abdominal obesity: a path model using self-efficacy and health-promoting behaviour. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(5):1087–97.

Armitage CJ, Wright CL, Parfitt G, Pegington M, Donnelly LS, Harvie MN. Self-efficacy for temptations is a better predictor of weight loss than motivation and global self-efficacy: evidence from two prospective studies among overweight/obese women at high risk of breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(2):254–8.

Barber L, Grawitch MJ, Munz DC. Are better sleepers more engaged workers? A self-regulatory approach to sleep hygiene and work engagement. Stress Health. 2013;29(4):307–16.

Barber LK, Munz DC, Bagsby PG, Powell ED. Sleep consistency and sufficiency: are both necessary for less psychological strain? Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress. 2010;26(3):186–93.

Zheng Y, Burke LE, Danford CA, Ewing LJ, Terry MA, Sereika SM. Patterns of self-weighing behavior and weight change in a weight loss trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016;40(9):1392–6.

Burke LE, Shiffman S, Music E, et al. Ecological momentary assessment in behavioral research: addressing technological and human participant challenges. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(3):e77.

Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4(1):1–32.

Sun R, Rohay JM, Sereika SM, Zheng Y, Yu Y, Burke LE. Psychometric evaluation of the Barriers to Healthy Eating Scale: results from four independent weight loss studies. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(5):700–6.

Enders CK, Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychol Methods. 2007;12(2):121–38.

Cressie N. Statistics for Spatial Data. New York: Wiley; 2015.

Harville DA. Maximum likelihood approaches to variance component estimation and to related problems. J Am Stat Assoc. 1977;72:320–38.

Wang J, Ye L, Zheng Y, Burke LE. Impact of perceived barriers to healthy eating on diet and weight in a 24-month behavioral weight loss trial. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015;47(5):432–436 e431.

Annesi JJ, Johnson PH, McEwen KL. Changes in self-efficacy for exercise and improved nutrition fostered by increased self-regulation among adults with obesity. J Primary Prevent. 2015;36(5):311–21.

Baranowski T, Lin L, Wetter D, Resnicow K, Hearn M. Theory as mediating variables: why aren’t community interventions working as desired? Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7(Suppl):S89–95.

Baumeister R, Bratslavsky E, Muraven M, Tice D. Ego depletion: is the active self a limited resource? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(5):1252–65.

Baumeister T, Vohs K, Tice D. The strength model of self-control. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16:351–5.

Diestel S, Rivkin W, Schmidt KH. Sleep quality and self-control capacity as protective resources in the daily emotional labor process: results from two diary studies. J Appl Psychol. 2015;100(3):809–27.

Fillo J, Alfano CA, Paulus DJ, et al. Emotion dysregulation explains relations between sleep disturbance and smoking quit-related cognition and behavior. Addict Behav. 2016;57:6–12.

Schmitt A, Belschak FD, Den Hartog DN. Feeling vital after a good night’s sleep: the interplay of energetic resources and self-efficacy for daily proactivity. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017;22(4):443–54.

Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016.

Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, Liu K, Rathouz PJ. Self-reported and measured sleep duration: how similar are they? Epidemiology. 2008;19(6):838–45.

Carroll R, Ruppert D, Stefanksi L, Crainiceanu C. Measurement error in nonlinear models: a modern perspective. Second ed: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2006.

Matthews KA, Patel SR, Pantesco EJ, et al. Similarities and differences in estimates of sleep duration by polysomnography, actigraphy, diary, and self-reported habitual sleep in a community sample. Sleep Health. 2018;4(1):96–103.

Cao Y, Wittert G, Taylor AW, Adams R, Shi Z. Associations between macronutrient intake and obstructive sleep apnoea as well as self-reported sleep symptoms: results from a cohort of community dwelling Australian men. Nutrients. 2016;8(4):207.

Verwimp J, Ameye L, Bruyneel M. Correlation between sleep parameters, physical activity and quality of life in somnolent moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea adult patients. Sleep Breath. 2013;17(3):1039–46.

Funding

This study was funded by the NIH, NHLBI: R01HL107370 (PI: L.E. Burke); R01HL107370-S (PI: Mendez, Diversity Supplement), K23HL118318 (PI: Kline).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in this study, which involved human participants, were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Pittsburgh and the National Institutes of Health and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study prior to any data collection.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burke, L.E., Kline, C.E., Mendez, D.D. et al. Nightly Variation in Sleep Influences Self-efficacy for Adhering to a Healthy Lifestyle: A Prospective Study. Int.J. Behav. Med. 29, 377–386 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-021-10022-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-021-10022-0