Abstract

Purpose

Medically unexplained symptoms (MUS) currently constitute the main diagnostic criterion of somatoform disorders. It has been proposed that the required dichotomization of somatic complaints into MUS and medically explained symptoms (MES) should be abandoned in DSM-V. The present study investigated complaints in the general population in order to evaluate the relevance of a distinction between MUS and MES.

Methods

Three hundred twenty-one participants from a population-based sample were interviewed by telephone to assess symptoms present during the previous 12 months. Complaints were examined in terms of health care use, diagnoses made by the physician and degree of impairment. At the 1-year follow-up, 244 subjects were re-interviewed in order to explore the stability of symptoms.

Results

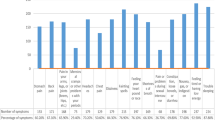

The complaints frequently prompted participants to seek medical health care (several pain and pseudoneurological symptoms led to a doctors' visit in >80 % of cases), although etiological findings rarely suggested a medical pathology (occasionally <30 %). MUS and MES proved, to an equal degree, to impair individuals and prompt a change in lifestyle. Pain caused the worst impairment compared with other symptoms. The most prevalent MUS and MES were characterized by a transient course (approximately 60 % remitted, 55 % newly emerged to follow-up), although various unexplained pain complaints tended to be persistent (e.g., back pain 67 %). Remarkably, the appraised etiology as explained or unexplained changed from baseline to follow-up in many persisting symptoms (20 % MUS → MES, 50 % MES → MUS).

Conclusions

In principal, MUS and MES resulted in comparable impairment and stability. Due to conceptual and methodological difficulties, classification criteria for somatoform disorders should not be restricted to somatic aspects of the symptomatology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Two persons with missing values in the PHQ-15 were not assigned to either of the two categories.

In order to facilitate statistical analyses due to the increased quantity of cases.

Complaints being most relevant in the population. Results of Fig. 2 could be confirmed taking all 49 symptoms into account.

Female-specific (n = 203).

References

Kroenke K, Price RK. Symptoms in the community: prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidity. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(21):2474–80.

Khan AA, Khan A, Harezlak J, Tu W, Kroenke K. Somatic symptoms in primary care: etiology and outcome. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(6):471–8.

Kroenke K, Mangelsdorff AD. Common symptoms in ambulatory care: incidence, evaluation, therapy, and outcome. Am J Med. 1989;86(3):262–6.

Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: an epidemiological study in seven specialities. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51(1):361–7.

Hiller W, Rief W, Braehler E. Somatization in the population: from mild bodily misperceptions to disabling symptoms. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(9):704–12.

Eriksen HR, Svendsrød R, Ursin G, Ursin H. Prevalence of subjective health complaints in the Nordic European countries in 1993. Eur J Public Health. 1998;8(4):294–8.

Wittchen HU, Jacobi F. Size and burden of mental disorders in Europe—a critical review and appraisal of 27 studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15(4):357–76.

Leiknes KA, Finset A, Moum T, Sandanger I. Methodological issues concerning lifetime medically unexplained and medically explained symptoms of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview: a prospective 11-year follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(2):169–79.

McFarlane AC, Ellis N, Barton C, Browne D, van Hooff M. The conundrum of medically unexplained symptoms: questions to consider. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(5):369–77.

Sharpe M, Mayou R, Walker J. Bodily symptoms: new approaches to classification. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(4):353–6.

Koch H, van Bokhoven MA, Bindels PJ, van der Weijden T, Dinant GJ, ter Riet G. The course of newly presented unexplained complaints in general practice patients: a prospective cohort study. Fam Pract. 2009;26(6):455–65.

Brown RJ. Introduction to the special issue on medically unexplained symptoms: background and future directions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(7):769–80.

Creed F. Medically unexplained symptoms—blurring the line between “mental” and “physical” in somatoform disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(3):185–7.

Dimsdale J, Creed F. The proposed diagnosis of somatic symptom disorders in DSM-V to replace somatoform disorders in DSM-IV—a preliminary report. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66(6):473–6.

Loewe B, Mundt C, Herzog W, Brunner R, Backenstrass M, Kronmueller K, et al. Validity of current somatoform disorder diagnoses: perspectives for classification in DSM-V and ICD-11. Psychopathology. 2008;41(1):4–9.

Hessel A, Geyer M, Hinz A, Braehler E. Utilization of the health care system due to somatoform complaints—results of a representative survey. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2005;51(1):38–56.

Fink P, Sørensen L, Engberg M, Holm M, Munk-Jørgensen P. Somatization in primary care: prevalence, health care utilization, and general practitioner recognition. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(4):330–8.

Dirkzwager AJ, Verhaak PF. Patients with persistent medically unexplained symptoms in general practice: characteristics and quality of care. BMC Fam Pract 2007;8(33).

Harris AM, Orav EJ, Bates DW, Barsky AJ. Somatization increases disability independent of comorbidity. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):155–61.

Kisely SR, Goldberg DP. The effect of physical ill health on the course of psychiatric disorder in general practice. BJP. 1997;170(6):536–40.

Kisely S, Goldberg D, Simon G. A comparison between somatic symptoms with and without clear organic cause: results of an international study. Psychol Med. 1997;27(5):1011–9.

Kisely S, Simon G. An international study comparing the effect of medically explained and unexplained somatic symptoms on psychosocial outcome. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(2):125–30.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Linzer M, Hahn SR, deGruy FV, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care: predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(9):774–9.

Robins LN. Using survey results to improve the validity of the standard psychiatric nomenclature. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(12):1188–94.

Rief W, Rojas G. Stability of somatoform symptoms—implications for classification. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(9):864–9.

Kroenke K, Jackson JL. Outcome in general medical patients presenting with common symptoms: a prospective study with a 2-week and a 3-month follow-up. Fam Pract. 1998;15(5):398–403.

Leiknes KA, Finset A, Moum T, Sandanger I. Course and predictors of medically unexplained pain symptoms in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(2):119–28.

Mewes R, Rief W, Braehler E, Martin A, Glaesmer H. Lower decision threshold for doctor visits as a predictor of health care use in somatoform disorders and in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(4):349–55.

Kingma EM, Tak LM, Huisman M, Rosmalen JG. Intelligence is negatively associated with the number of functional somatic symptoms. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(11):900–5.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, deGruy FV, Swindle R. A symptom checklist to screen for somatoform disorders in primary care. Psychosomatics. 1998;39(3):263–72.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(2):258–66.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Loewe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–59.

WHO. Schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry (SCAN). Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1995.

Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):37–46.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74.

Feinstein AR, Cicchetti DV. High agreement but low kappa: I. The problems of two paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(6):543–9.

Shankar V, Bangdiwala SI. Behavior of agreement measures in the presence of zero cells and biased marginal distributions. J Appl Stat. 2008;35(4):445–64.

Rief W, Nanke A, Emmerich J, Bender A, Zech T. Causal illness attributions in somatoform disorders: associations with comorbidity and illness behavior. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(4):367–71.

Rief W, Mewes R, Martin A, Glaesmer H, Braehler E. Are psychological features useful in classifying patients with somatic symptoms? Psychosom Med. 2010;72(7):648–55.

Simon GE, Gureje O. Stability of somatization disorder and somatization symptoms among primary care patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(1):90–5.

Sharpe M, Stone J, Hibberd C, Warlow C, Duncan R, Coleman R, et al. Neurology out-patients with symptoms unexplained by disease: illness beliefs and financial benefits predict 1-year outcome. Psychol Med. 2010;40(4):689–98.

Martin A, Buech A, Schwenk C, Rief W. Memory bias for health-related information in somatoform disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(6):663–71.

Pauli P, Alpers GW. Memory bias in patients with hypochondriasis and somatoform pain disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(1):45–53.

Grabe HJ, Meyer C, Hapke U, Rumpf HJ, Freyberger HJ, Dilling H, et al. Somatoform pain disorder in the general population. Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72(2):88–94.

Froehlich C, Jacobi F, Wittchen HU. DSM-IV pain disorder in the general population: an exploration of the structure and threshold of medically unexplained pain symptoms. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(3):187–96.

Creed F, Guthrie E, Fink P, Henningsen P, Rief W, Sharpe M, et al. Is there a better term than “medically unexplained symptoms”? J Psychosom Res. 2010;68(1):5–8.

Deary V, Chalder T, Sharpe M. The cognitive behavioural model of medically unexplained symptoms: a theoretical and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(7):781–97.

Rief W, Broadbent E. Explaining medically unexplained symptoms—models and mechanisms. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(7):821–41.

Sharpe M, Mayou R. Somatoform disorders: a help or hindrance to good patient care? Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184(6):465–7.

Henningsen P, Fink P, Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Rief W. Terminology, classification and concepts. In: Creed F, Henningsen P, Fink P, editors. Medically unexplained symptoms, somatisation and bodily distress. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

Rief W, Sharpe M. Somatoform disorders—new approaches to classification, conceptualization, and treatment. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(4):387–90.

Martin A, Rief W. Relevance of cognitive and behavioral factors in medically unexplained syndromes and somatoform disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34(3):565–78.

Hausteiner C, Bornschein S, Bubel E, Groben S, Lahmann C, Grosber M, et al. Psychobehavioral predictors of somatoform disorders in patients with suspected allergies. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(9):1004–11.

Voigt K, Nagel A, Meyer B, Langs G, Braukhaus C, Loewe B. Towards positive diagnostic criteria: a systematic review of somatoform disorder diagnoses and suggestions for future classification. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68(5):403–14.

Rief W, Mewes R, Martin A, Glaesmer H, Braehler E. Evaluating new proposals for the psychiatric classification of patients with multiple somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(9):760–8.

Steinbrecher N, Koerber S, Frieser D, Hiller W. The prevalence of medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(3):263–71.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the German Research Foundation to Rief, Brähler & Martin (DFG RI 574/14-1). The authors declare no conflicts of interest that could have influenced this study and its report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Klaus, K., Rief, W., Brähler, E. et al. The Distinction Between “Medically Unexplained” and “Medically Explained” in the Context of Somatoform Disorders. Int.J. Behav. Med. 20, 161–171 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9245-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9245-2