Abstract

Animal remains from twelve Iron Age (ca. 500 BC–1200/1300AD) sites from Southern and Western Finland, showing a mixture of finds and features typical of both settlement sites and cemeteries, were investigated using a zooarchaeological, taphonomic and contextual approach. Rarefaction analysis of the species richness and anatomical distribution indicates that the samples included both general domestic waste type and species and element-selective deposits of cattle and horse skulls, mandibles and limb bones. According to radiocarbon dating results, there seems to be a gap between the dates of burials and those of other ritual activities, indicating that the context of such deposits is a disused cemetery. The faunal deposits could represent remembrance rituals or relate to votive offerings intended to ensure healthy or productive livestock, a practice described in later ethnographic sources. These deposits seem to be in use within a large geographical area over a long period, and some aspects of this belief system may even have survived into the Christianisation of society in the historical period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Faunal remains recovered from archaeological sites give valuable data for the interpretation of a site’s character and activities practiced in them. The identification of various activities such as slaughter, butchery, consumption, crafts and rituals in the zooarchaeological record is a complex process and has been previously discussed in detail, with particular regard to the interpretation of ritual and domestic waste (Lentacker et al. 2004; Kunen et al. 2002; Broderick 2012; Magnell 2012; Hukantaival and Bläuer 2017; Macheridis 2017; Gaastra 2017). Studying the conscious decisions to select certain species, individuals of a certain age or sex, specific skeletal elements or the particular details of slaughter, and the treatment of the carcass may reveal the human selection patterns behind the material (Hill 1995; Magnell 2012; Morris 2012; Russell 2012; Hukantaival and Bläuer 2017; Gaastra 2017; Bläuer et al. 2019). Combined with archaeological contextual data and compared with other faunal deposits, patterns in acts of deposition can be discerned. The presence of butchery marks or the evidence of primary or secondary deposition—e.g. presence of open epiphysis-metaphysis pairs, intact fragile elements, weathering or burning—further increases the knowledge of the deposition history of the site (e.g. Lyman 1994; Yeshurun et al. 2014). Identifying these activities in the faunal material helps us to interpret the function of the site and study the economic and social animal utilisation pattern.

There are many potential definitions for ritual and for the archaeological material cultural expressions (e.g. Merrifield 1988, Bell 1992, Insoll 2004, Snoek 2006, Hukantaival 2016). In this paper, the focus is on the process and different degrees of ritualisation, instead of strict dichotomy between mundane and ritual acts (Grimes 2014). Also, the focus is on the identification of the purpose of the deposit. Thus, ritualising acts are seen especially from the perspective of intentionally applying different techniques possibly creating a sense of social belonging or connection and/or an intention to affect the order within one’s realm either by maintaining the status quo or by changing it (cf. Snoek 2006; Wulf 2006; Hukantaival 2016).

Middle and Late Iron Age in Southwest Finland, Pirkanmaa and Häme

Finland was not culturally homogenous during the Middle and Late Iron Age. This is demonstrated by the variation in material culture, as well as cemetery and burial types. The period is characterised by the spreading of the furnished cemeteries from Coastal Southwest (SW) and Western Finland to the inland Finland, including Pirkanmaa and Häme (Raninen and Wessman 2015). These cemeteries are usually found in clusters by the waterways of lakes and rivers (Raninen and Wessman 2014). In this period, subsistence patterns are assumed to have consisted of permanent field cultivation, slash and burn cultivation, animal husbandry, hunting and fishing, although the available environmental evidence in the studied area is scarce (Schultz and Schultz 1992; Vuorinen 2009; Raninen and Wessman 2014, 2015; Bläuer 2017; Lempiäinen-Avci 2017; Lahtinen et al. 2017). Finland’s interior was also inhabited by mobile hunter-gatherer groups (e.g. Taavitsainen et al. 2007, summary in Raninen and Wessman 2014). These societies were likely to be organised as local autonomous groups without central leadership but with lively trade contacts to other societies around Baltic Sea (Asplund 2008; Raninen 2010; Raninen and Wessman 2014, 2015).

Typical Iron Age sites for this area are cemeteries exhibiting a variety of burial customs, e.g. individual cremation burials in urns, cremation cemeteries under level ground, various stone settings with collective burials, inhumation burials and cairns with inhumations or cremations (Pihlman 1999; Wessman 2010; Raninen and Wessman 2015). Settlement sites are also known, though to a lesser extent, and with the exception of the Late Iron Age, with little preserved organic material (e.g. Lehtosalo 1964; Uino 1986; Kotivuori 1992; Schultz and Schultz 1992; Vuorinen 2009; Deckwirth 2008; Bläuer and Kantanen 2013; Raninen and Wessman 2015; Bläuer 2017). The third group of sites are ‘sacrificial’ cairns—cairns of mixed earth and stone containing prehistoric material (pottery, burnt clay, slag, bones, stone objects) but not burials (Muhonen 2008). However, defining these cairns is challenging because they do not form a uniform group (Muhonen 2008). Burial cairns or cemeteries may also include finds typical of settlement sites (e.g. Asplund et al. 2019), and otherwise typical sacrificial cairns may also include a few human bone fragments (Raike and Seppälä 2005; Muhonen 2008). In practice, however, a number of Iron Age sites show a mixture of finds and features, including stone settings, cairns, burnt clay (daub), pottery fragments, iron slag, animal bones and stone and metal artefacts. Some include human bone material. Thus, there are various interpretations for these sites or the activities that created them, including settlement sites, refuse heaps, cemeteries or ritual sites (Kivikoski 1969; Sarkamo 1970, 1984; Taavitsainen 1992; Salo 2004; Muhonen 2008, 2009; Wessman 2010; Asplund et al. 2019). The various materials found at these sites and the interpretations presented for them are aptly summarised in the title of Taavitsainen’s (1992) article ‘Cemeteries or refuse heaps?’.

In SW Finland, Pirkanmaa and Häme several Iron Age (ca. 500 BC–1200/1300AD) sites include unburnt faunal material which has not previously been analysed using contextual or taphonomic approaches. The interpretation of many of these sites has been previously debated, as they show a mixture of finds and features typical of both settlement sites and cemeteries (Kivikoski 1969; Sarkamo 1970, 1984; Taavitsainen 1992; Salo 2004; Muhonen 2008, 2009; Wessman 2010; Asplund et al. 2019). Increased radiocarbon dating and osteological analyses of bone material have recently demonstrated that artefacts and human and animal bones from cemeteries, originally interpreted as representing a single depositional event, may actually have been deposited hundreds of years apart (e.g. Mäntylä-Asplund and Storå 2010; Asplund 2011; Tourunen 2011; Asplund et al. 2019). One of the sites included in this study, Sastamala Ristimäki, was recently re-examined (Asplund et al. 2019). The earth-stone mixed cairn was originally interpreted as a single burial cairn. However, after new analysis of the finds and radiocarbon dates, three distinct elements in its construction were identified. These comprised an inhumation burial dating to the fourth century AD, a later ritual earth and stone mixed cairn, dating to between the fifth and eighth centuries AD, and a cluster of human bones in a secondary context. The earth and stone mixed cairn included both settlement material in secondary contexts (e.g. pottery, burnt clay, burnt and unburnt animal bones), separate offerings, such as a partial sheep skeleton, and a separate cluster of secondarily placed human bones in the middle layers of the cairn. The secondary human bones were dated to between the first century BC and the second centuries AD, thus predating all the other features. This study provides an example of the possible complexity of the depositional history of Iron Age cairns and highlights the need for further studies.

Belief system and archaeological material

In the absence of written sources, the evidence available for the study of the Finnish Iron Age belief system consists of archaeological and ethnographic material (e.g. Krohn 1915; Muhonen 2009; Wessman 2010; Frog 2017; Hukantaival and Bläuer 2017). However, our knowledge of it is fragmentary at best, and no summary of this data exists at present. Therefore, modern knowledge both of the rituals and beliefs of Finland’s Iron Age population in general, and of the potential geographic variation of their beliefs in particular, is scarce. Within the ethnographic material, ritual practices that have potential to leave physical remnants to the archaeological site are sometimes described, and studies combining both ethnographic data and archaeological material have been conducted (e.g. Muhonen 2009; Hukantaival 2016; Hukantaival and Bläuer 2017).

Among the themes discussed in the context of Iron Age beliefs are offerings (e.g. animal parts or bones) made to cairns or near stones. (e.g. Marjakorpi 1910; Krohn 1915; summary in Muhonen 2009). This practice was still known in the nineteenth century. Marjakorpi (1910) describes the story of a farmer’s wife offering food to a snake in the stone cairn in Heinola in order to bring good luck to the cattle. Animal bones were reportedly present in the cairn (Marjakorpi 1910). In Northern Finland, sacred Sámi sites also include animal bones interpreted as offerings (Äikäs et al. 2009, see also Muhonen 2008). Thus, animal bones found in cairns could derive also from the later, historical period. Other concepts present in ethnographic material that have been used when interpreting archaeological sites are ‘väki’, a magical force which could be associated with, e.g. fire, iron or water, and ‘kalma’, that could mean death or harmful force. With certain rites, these concepts were used in attempts to cure illnesses or as protection against evil forces, as well as to cause harm (Krohn 1915; Talve 1997).

Ethnographic material also describes remembrance meals taking place at the cemetery at regular intervals after the death of the family member (e.g. Waronen 1898; Krohn 1915: summary in Muhonen 2009). The re-use of Iron Age cemeteries is a regularly documented phenomenon in the archaeological record, interpreted as the commemoration and remembrance of the dead or as death and fertility rituals (Pihlman 1999; Wickholm 2008; Wessman 2010; Holmblad 2013). If animal bones on burial sites are remnants of remembrance meals for the family members, as described in the ethnographic sources, they should date to the same period of use as the burial activity, since they are made by the family of the deceased. Animal bones dating to later periods require different explanation, e.g. ritual activities when the cemeteries were no longer in active use (c.f. Wessman 2010).

Aims of this study

This paper examines animal bone assemblages from twelve Finnish Iron Age sites in Southern and Western Finland with unburnt faunal material (Fig. 1, Table 1). These sites include cemeteries or burial sites, ritual cairns and ambiguous sites with no clear interpretation. The Iron Age in Finland is chronologically divided into the Early (ca. 500 BC–375/400 AD), Middle (ca. 375/400–800/825 AD) and Late (ca. 800/825–1200/1300 AD) (Raninen and Wessman 2015) Iron Age Periods. Many sites discussed in this paper were used during several of these periods, though the main periods discussed here are the Middle and Late Iron Ages. This is the first time these materials have been interpreted within a social zooarchaeological and taphonomic frame. Due to the poor preservation of the bone material in Finland’s generally acidic soil and the paucity of excavated settlement sites dating to the Iron Age, animal bones from these sites form a significant portion of the unburnt bone material surviving from the Finnish Iron Age, especially prior to the Late Iron Age. These bones therefore provide a very important source of evidence for research of past animal exploitation and human-animal relationships in Finland, providing an important contribution, for example, to larger projects studying the development of animal husbandry in Finland.Footnote 1

Sites used in this study. (1) Paimio Spurila, (2) Laitila Kylämäki, (3) Sastamala Kalliala, (4) Sastamala Kirkkovainionmäki, (5) Sastamala Ristimäki, (6) Nokia Pappila, (7) Nokia Tapanila, (8) Nokia Pääskylä (not shown separately, same as 9), (9) Nokia Viik, (10) Pälkäne Hylli, (11) Hattula Myllymäki and (12) Hämeenlinna Riihimäki

Bone material is examined from several perspectives to understand the process of its deposition, the context of the deposition and the emerging patterns of behaviour that lie behind the deposition. First, the results of zooarchaeological analyses are investigated, with a special emphasis on species variation and anatomical distribution. Second, bones are set within the context of their place of deposition and of other archaeological material. This includes radiocarbon dating of selected bones and a comparison between the archaeological data and the role of animals in society in general. Third, the intention of the deposit is studied through a consideration of the nature of the bone material, combined with its spatial and temporal context and ethnographical background.

Materials and methods

This study includes bone material from twelve sites, a total of twenty separate features (Table 1) from Southern/Western Finland (regions SW Finland, Tavastia and Pirkanmaa, Fig. 1, coordinates in Online Resource 1). Bone material from six sites was previously completely unanalysed, two were partly analysed and four completely analysed (Table 1). For this study, the bone material from Sastamala Kalliala and Kirkkovainionmäki (TYA 82 and TYA 205, 222, previous analysis by Vormisto 1985) was reanalysed, and previous identifications were clarified. This study focused on animal bones. With the exception of isolated fragments, human bones were only marked as present but not identified further. Bones recovered from modern dump layers were removed from the analysis. Animal age data was only collected from the samples analysed for this study, because in previous osteological analyses, a variety of recording methods were used. The dating of artefacts and lists of finds were obtained from the original excavation reports. In some cases, the dating of the finds was re-evaluated, and this is mentioned separately in the text. For quantification of species abundance and anatomical distribution, the number of identified specimens (NISP) was used. NISP is the most common quantification method used in the zooarchaeological analysis in Finland and thus available for inter-site comparisons. Also, its pros and cons are known and well-documented (as summarised in Lyman 2018).

Animal age was determined by the degree of fusion of the epiphyses of the long bones (open, closing and fused, as defined in Bull and Payne 1982) and dental eruption and wear (by Grant 1982 and O’Connor 2003). This data was not available from the previously analysed samples from Hattula Myllymäki and Hämeenlinna Riihimäki. Species diversity was examined by rarefaction, a method that reflects the species richness within each sample. Within the zooarchaeological material, the number of identified species tends to increase with the sample size. Thus, it is challenging to compare species richness of small and large assemblages. Rarefaction enables such comparisons by making larger samples probabilistically smaller. It returns mean number of taxa to be expected at a given sample size (Lyman and Ames 2007; Gifford-Gonzalez 2018). The rarefaction curve was generated by using PAST V.4.01 software (Hammer 2020). The results should be interpreted with the limitations of the current material in mind, in particular the potentially complex formation processes and uncertain dating of the material.

Most of the features studied consist of cairns of mixed earth and stone (Table 1). At the Pälkäne Hylli site, natural boulders were used as the central stones of the structure, and in two of the cairns, hearths were identified during the excavations (Sarasmo 1959). At Nokia Viik (TYA 337, 426), three separate building phases of complex cairns have been identified (Renvall 1987; Koivisto 1988). Paimio Spurila (TYA 211) is a cremation cemetery (Luoto 1985). At Nokia Pääskylä 1 and 2 (TYA 485, 497), the features are not described as cairns but unambiguous structures with stones and soil (Pietikäinen 1989; Nurminen 1990; Spoof 1991). One of the studied features at Nokia Pappila 3 (TYA 616, 622) was described as a stone setting (Sipilä 1995, 1996). At Hattula Myllymäki 4 and 152 (KM 19704, 19,872) and Hämeenlinna Riihimäki (KM 30304) (Sarvas 1976, 1977; Seppälä 1998), structures were also described as stone settings.

Results

A total of 1024 identified animal bones (NISP, number of identified specimens, Table 2) were identified from all sites. The material included only one clear ‘associated bone group’—in this case, the partial skeleton of a sheep (Sastamala Ristimäki, Asplund et al. 2019). Thus, most of the material is disarticulated. In disarticulated material, no associated epiphysis-metaphysis pairs were observed. The most abundant species was cattle (Bos taurus), followed by horse (Equus caballus). Other identified mammal species were sheep (Ovis aries), pig (Sus scrofa), dog (Canis familiaris), cat (Felis catus),Footnote 2 bear (Ursus arctos), fox (Vulpes vulpes), European elk (Alces alces), European beaver (Castor fiber), hare (Lepus timidus) and unidentified genus/genera of seal (Phocidae). Fish species included bones from northern pike (Esox lucius), zander (Sander lucioperca), perch (Perca fluviatilis), burbot (Lota lota), cyprinids and fish of the salmon family. Among bird bones, domestic chicken (Gallus domesticus) and unidentified duck (Anas sp.) were present. In addition, bones of micro-fauna such as small rodents were recorded but not included in this study (Online Resource 2). Cattle bones are present in 17 archaeological features, horse bones in 16, sheep or goat bones in 13 and pig bones in 10.

The bone material included both burnt and unburnt fragments (Table 3). While most of the bones of major domesticates are unburnt, all the recovered bones from dog, fox and brown bear were burnt. Burnt animal bones are present in twelve features (Online Resource 2). Unburnt human bone was recovered from three sites (Sastamala Ristimäki, Nokia Pappila 2 and Hattula Myllymäki 152) and burnt human bones from a total of twelve features.

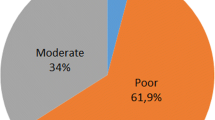

The number of identified animal bones in one feature varied from one to more than 200 (Table 2). The bone samples showed variable numbers of identified taxa. Four sites had more than 100 identified animal bone fragments (Sastamala Ristimäki, Hattula Myllymäki 4 and 152, Nokia Pappila 2). The first three of these possess the greatest number of identified species, and the rarefaction analyses of these exhibit similar ranges (Fig. 2). However, Nokia Pappila 2 have fewer identified species. The range area for each site represents the probabilistic number of taxa in given sample size. Thus, if the ranges do not overlap, the difference in the species diversity is not likely to be caused by the small sample size. Based on the rarefaction model, Sastamala Kalliala and Nokia Viik are more likely to represent high species diversity, while Paimio Spurila, Laitila Kylämäki 1 and Nokia Tapanila exhibit more selective characters, consisting only of a few species, mainly cattle and horse. For Riihimäki Kirstula, there is too little data for conclusions to be drawn, since its range overlaps that of many other sites.

Rarefaction curves of faunal assemblages modelling number of taxa versus different sample sizes (samples with NISP over 25). Generated by using PAST V.4.01 (Hammer 2020)

The samples also exhibited some variation in anatomical representation. The anatomical distribution of cattle and horse bones was studied, including bones categorised as large ungulates, as well as anatomical distribution of sheep, goat and pig bones, including bones categorised as small ungulates (Figs. 3 and 4). Faunal material from the Late Iron Age Pirkkala Tursiannotko settlement site is used for reference purposes (Bläuer 2017; Raninen 2017). The data is presented separately for burnt and unburnt bones and for each site studied. Elements from the head included the skull, mandibular and tooth fragments; those from the trunk included the vertebrae, ribs and sternum; those from the upper limbs included the scapula, humerus, ulna, radius, pelvis, femur and tibia; and the lower limbs included the carpal and tarsal bones, metapodials and phalanges. All the main anatomical groups are present in both burnt and unburnt material; however, the burnt fraction is likely to be more fragmented, and the bones from lower limbs are more often identified (Tourunen 2011). For large ungulates, elements from the head were dominant in most samples. These were mostly teeth. The exceptions were Sastamala Ristimäki, Nokia Viik and Pälkäne Hylli 3, but even here elements from the head are more common than in the settlement site of Pirkkala Tursiannotko. Nokia Pappila 2 also exhibited more variable anatomical distribution than most of the other samples. For small ungulates, elements from the head are dominant at Hämeenlinna Riihimäki and Nokia Tapanila, while the Sastamala, Nokia Viika and Hattula sites represent more variable distributions.

Anatomical distribution of the sheep, goat, pig and small ungulate bones (sites with NISP 5 or over). Pirkkala Tursiannotko is a settlement site for a reference. Burnt and unburnt bones are presented separately and together for each site. For a closer definition of anatomical elements belonging to each group, see the text

The assemblages are too small for a detailed analysis of cut marks and age profiles (Online Resource 3). This data was not reported in the previously analysed assemblages of Hattula Myllymäki or Hämeenlinna Riihimäki. All five horse epiphyses were fused (two scapulae, first phalanx, proximal tibia and proximal humerus). Cattle age data was collected from epiphysis and tooth wear. One tibia was from a calf. One metatarsal, two distal metapodial fragments and two calcanei were unfused. One distal tibia, a distal humerus and a distal radius from Nokia Pappila 2 and one distal tibia from Paimio Spurila were fused. The sample included both the fourth lower milk teeth (pd4) and lower third molars (M3) of cattle. This indicates the presence of both juvenile or sub-adult and adult or elderly animals (Grant 1982; O’Connor 2003). There were also eleven cut marks observed in the material, in cattle, horse, large and small ungulate and unidentified bones. These are indicative of meat removal (e.g. cuts on small ungulate ribs) or the cutting of a carcass into smaller portions (e.g. cutting through the sacrum of large ungulates).

All the features studied included unburnt animal bones, as this was the primary factor used for selecting the material (Online Resource 4). A total of 11 features included human bones, ranging from a partly preserved inhumation burial (Sastamala Ristimäki) to one burnt human skull fragment (Sastamala Kirkkovainionmäki).Footnote 3 All 20 features included pottery fragments and burnt clay, and 18 also included flakes of stone and small metal objects other than weapons (nails, knives etc.). Iron slag and clay objects, such as mould and disc fragments, were also frequently present. It seems that human bones, weapons and jewellery (metal and glass) are often but not always found within the same features.

Nine unburnt animal bones and one unburnt human bone were selected for radiocarbon dating (Table 4). The results range from the seventh century AD to the historical or modern period, most dating to the Late Iron Age (Figs. 5 and 6). These results did not accord with the dating of the artefacts found at these sites, but they reflected the previous results from Sastamala Ristimäki (Asplund et al. 2019), where unburnt animal bone dated to a more recent period than human bones or artefacts assumed to belong to a burial (Fig. 6, see Online Resource 5 for summary dating table).

Discussion

Context of the deposition and chronological circumstances

Many of the sites examined here show evidence of various activities and multi-period use, and many show evidence of burial activities predating the deposition of animal bones within the context of a cremation cemetery (Paimio Spurila) or earth and stone mixed cairn (Sastamala Ristimäki and Nokia Pappila 2, Nokia Tapanila). At Laitila Kylämäki, the adjacent cemetery predates the cairn, which was built almost on top of it. At Nokia Viik, unburnt bone material has been found in the youngest part of the cairn complex, an earth mound built on top of two older burial cairns. There is one exception: a pottery fragment from the stone-earth structure at Hämeenlinna Riihimäki seems to predate the adjacent cemetery (Online Resource 5). The context of deposition of these unburnt animal bones thus seems often to be an old burial ground or cemetery. Yet some of the materials studied are not associated, at least directly, with any known cemetery site. However, the similarity of the find material and feature structure (earth and stone mixed cairn) indicates that all the sites studied here may include material from ritual activity based on the same patterns.

The earliest radiocarbon dating of unburnt animal bone material is from Sastamala Ristimäki (sixth to seventh centuries AD), and the practice seems to continue at least until the end of the Iron Age (eleventh–thirteenth centuries). There seems to be a chronological gap in the current data between the sites’ burial phases and the later deposition of animal bones, but this may partly result from a paucity of dated animal bones, pottery and burials. Even if there is a gap in the record of use within one part of a cemetery, the wider area may still have been in active use. Many cemetery sites show evidence of a long period of use, from the Early to Late Iron Ages (e.g. Mäntylä-Asplund and Storå 2010; Wessman 2010). The sites examined here are in the southern and western parts of Finland (the regions of Tavastia, Pirkanmaa and SW Finland). A similar tradition of animal bone deposition in the old cemetery context therefore seems to be in evidence across a wide geographical area, potentially beyond the area presently studied, since cairns similar to those studied here are present in, e.g. Eastern Finland (Muhonen 2008).

The animal bone assemblages from these sites have been formed by different activities and purposes. Some of the unburnt material may represent special ritual depositions of selected animals and of animal elements such as the skulls, mandibles and teeth or the limb bones of horses and cattle or (semi)-complete animals. In addition, some may relate to primary burial activities such as burnt dog and bear bones. Their presence within a feature may be the result of intentional or unintentional mixing, although without radiocarbon dating their belonging to later rituals cannot be excluded. It should also be noted that burnt bear claws (from hides) and dog bones mixed with human material are common finds in cremation cemeteries under flat ground in Finland (Formisto 1996). In the cairns studied, such finds are only found alongside burnt human bone and thus probably belong to cemetery material mixed with cairn material, which in Laitila Kylämäki, for example, is located very near to or even partly overlaps the cemetery (Lehtosalo 1964). Some unburnt and burnt animal bones may be connected with the secondary deposition of settlement debris, thus obscuring the dichotomous interpretation given to mundane settlement site waste and ritual material. There is still little data available concerning the dating of burnt animal bone material. However, in Sastamala Ristimäki and Kalliala, both burnt and unburnt animal bones are found in the same contexts, and there is no evidence of cremation burials in the features. The material, both burnt and unburnt, could be explained by the ritualisation process of the domestic material. Moreover, the sites contain material from the historical period, with some cairns showing evidence of use during the historical or modern period. A horseshoe from Laitila Kylämäki 4 and a brass ring dating from the historical period from Nokia Haapaniemi Pääskylä (TYA 485:1) are evidence of later deposition events. A horse pelvis from a stone cairn from the region of Hattula Myllymäki (Luho 1953) has been radiocarbon dated to the fifteenth-seventeenth centuries. During the twentieth century, some of these sites (e.g. Nokia Tapanila) were sometimes been used as waste dumps. Burrowing micro-fauna (probably including the cat bones from Sastamala Ristimäki, see Asplund et al. 2019) are also present.

Formation and selection of animal bone material

Generally, disarticulated faunal material consists mostly of unburnt cattle and horse bones. However, some sites show more variation, both in species and anatomical distribution. Larger bone samples were found in Sastamala Ristimäki, Hattula Myllymäki 4 and 152 and Nokia Pappila 2. The Ristimäki and Myllymäki sites also present higher species richness, and according to rarefaction analysis, Nokia Viik and Sastamala Kalliala are also likely to exhibit a similar pattern. For large ungulates, Sastamala Ristimäki and Nokia Viik also show a more varied anatomical distribution. For small ungulates, anatomical variation is high in Sastamala Kalliala and Ristimäki, Nokia Viik and Hattula sites. Previously, disarticulated bone material from Sastamala Ristimäki has been interpreted as being derived from ritually redeposited settlement debris—this is the most likely explanation for the variety and character of the archaeological material found in the cairn (Asplund et al. 2019). If the faunal remains were transported to a cairn with settlement soil, this could mean that the animal species, element distribution and preservation (burnt/unburnt) was unaffected by intentional selection. The other option is ritual deposition, with little importance given to the species or element selected. The same pattern may also apply to Nokia Viik and Sastamala Kalliala, where archaeological find material also resembles that present in Ristimäki.

This is in contrast to Nokia Pappila 2, Nokia Tapanila, Paimio Spurila and Laitila Kylämäki, which, according to rarefaction analysis, are likely to represent samples with lower species richness. Some deposits seem also to contain a wider selection of species and/or anatomical parts, namely, unburnt elements from the heads and limbs of cattle and horses (Paimio Spurila, Epaala Hylli, Laitila Kylämäki). The Myllymäki sites in particular and perhaps also Ristimäki could be best explained as a mixture of domestic waste and additional deposits of large ungulate heads and limbs exhibiting high species richness, variable anatomical distribution of small ungulates and high numbers of large ungulates skulls and lower limb. As the formation process of cases studied can be complex, the rarefaction analysis might also emphasise the richness of mixed samples with species typical both of domestic waste and of ritual deposits. The contents of the Nokia Pappila 2 site are perhaps best described as domestic waste with low species richness.

Within the area studied, no large animal bone assemblages have been excavated from a Middle Iron Age settlement context. It is therefore impossible to compare settlement site bone material from Sastamala Ristimäki that has possibly been re-deposited with settlement waste identified from the same period. The main domestic mammal species recovered from Late Iron Age settlement sites include pig, cattle and sheep or goat bones in roughly the same proportions (ca. 30% each) and horse bones to a lesser extent (under 10%) (Online Resource 5, Schultz and Schultz 1992; Vuorinen 2009 with discussion and reinterpretation in Hukantaival and Bläuer 2017; Bläuer 2017). Bones of game animals are also present, but domestic species dominate the samples. Perhaps the most notable difference in the settlement site material and the animal bone assemblages in this study is the large number of pig bones in the former and the small number of pig bones and large number of horse bones in the latter. Thus, there seems to be a tendency to select horse bones for these features and avoid the deposition of pig bones.

Elements from the head and especially unburnt loose teeth are dominant in the sample. Tooth enamel is the hardest part of the skeleton: poorly preserved samples therefore often include a high proportion of teeth. However, the currently researched faunal material is usually moderately well preserved. Furthermore, in the case of decayed skulls or mandibles, a row of teeth should be present instead of a single tooth. The skulls, mandibles and loose teeth are therefore common elements chosen for ritual deposition in the burial context (Hårding 2002; Carlie 2004; Wessman 2010; Bläuer et al. 2013; Hukantaival 2016).

Intention of the deposition

The faunal material from the sites studied offers new data about the belief system and rituals of Iron Age society in Finland. The results also emphasise the importance of comparing ethnographical data with archaeological material when assuming beliefs recorded in historical period have prehistorical roots (c.f. Hukantaival and Bläuer 2017). The faunal material studied here cannot be directly explained by the practices or beliefs described in the ethnographic material, such as sacrificing to the cairns or remembrance meals in the cemeteries. While the deposition of animal bones and other material at the cairns as a physical act seems to continue into the historical period, creating a possible continuum of pre-Christian beliefs within Finnish Christian society, the purpose behind the act may have changed. However, the current data is insufficient to study this change in detail.

The species that have entered these sites as part of settlement debris were not especially selected for ritual reasons. It has previously been suggested that the deposition of settlement material in an old cemetery may have been made in order to provide a ritually safe or acceptable place for waste that was seen as needing a ‘proper’ place of deposition (Asplund et al. 2019). Indeed, this may also explain the presence of some personal objects (jewellery, weapons) or objects relating to iron, which were seen as holding special power, ‘väki’ in later Finnish folklore (slag, old casts Krohn 1915). It should also be noted that some objects dating to the historical period (rings, horseshoes) fit this interpretation, especially since rings were used to cure joint illnesses like gout.Footnote 4

The unburnt depositions of horse and cattle bones may be related to offerings. Such offerings represent a more selective range of material. The animals concerned include at least horse, cattle and sheep. These are linked to husbandry and domestic animal uses. This could relate to emphasizing the farming component in subsistence in societies where hunter-gatherers were still present in the same area (c.f. Bläuer et al. 2013); however, such an explanation is unlikely for the sites in SW Finland. The paucity of pig remains in secondary depositions is noteworthy, as they are abundant in Late Iron Age domestic waste material. Horse and cattle were large and valuable animals. Their selection may have been based on their value as suitably expensive gifts. Such faunal remains may relate to commemorating the dead (Wessman 2010). Since a gap appears to have existed, at least in some cases, between burial activity and animal bone deposition, the context of the deposition is old burial place, and the faunal remains are not likely to be remains from funeral feast as described in the ethnographic sources. In this case, these bones may have been offerings to the ancestors, and the concept of the ancestor does not in this case necessarily mean only genetic relatives or direct family members. At the present, there is little knowledge available concerning the population migration or possible population change in the area studied. Thus, the actual genetic or social relationship between the earlier and later societies remains unknown. It is also possible that the offerings made at these sites are related to the idea of a more general power being present there because of the presence of human remains, perhaps related to ‘kalma’. They may also have been motivated by a desire to protect horse and cattle from harm, disease and accidents. Such protection may have been an aspect of these depositions as evident in the offerings described in later ethnographic material.

Conclusions

This study reveals new evidence for the ritual use of animal bones in Southern and Western Finland during the Iron Age. A zooarchaeological, taphonomic and contextual approach is a useful tool for interpreting sites with complex find material. The animal bone material from the sites investigated seems to be the result of several activities. During the Iron Age, the ritual deposition of settlement debris and more specific ritual offerings were performed at old cemetery sites and/or various stone structures. These sites therefore form long-lived ritual complexes, where various activities such as burials, offerings or the ritual disposal of settlement waste took place. The active use of these sites for centuries over a large geographical area also seems to imply a continuity, and in some respect a similarity, of beliefs in Middle and Late Iron Age Finland, though the details and true extent of this phenomenon remain to be studied. Some aspects of this belief system may even have remained active during the Christianisation of society in the historical period.

Availability of data and material (data transparency)

Not applicable.

Notes

BoNe: Borrowing from the neighbour: Animal husbandry methods and cultural contacts in the Northern Baltic Sea region during prehistoric and historical periods, Academy of Finland Grant SA286499

Cat bones were recovered in the same context with modern water voles from the Sastamala Ristimäki cairn, and they may be recent (Asplund et al. 2019).

For some reason, in Vormisto’s (1985) original analysis, this human bone is not mentioned.

A similar ring is found in the collections of the Turku Museum Centre (TMM16429:3), labelled as a ‘gout ring’, but with an inscription inside: ‘Äkta Elektrisk Giktring JW Sundberg Eskilstuna Smedjegatan 9 Etablerad 1849—Skyddsmärke’ (‘Real Electronic Gout Ring’). Finna database.

References

Äikäs T, Puputti AK, Núñez M, Aspi J, Okkonen J (2009) Sacred and profane livelihood: animal bones from Sieidi sites in northern Finland. Nor Archaeol Rev 42(2):109–122

Andors AV (1977) An Iron Age fauna from Retulansaari, Southern Finland. Osteological report. Archives of NBA, Finland

Asplund H (2008) Kymittæ. Sites, centrality and long-term settlement change in the Kemiönsaari region in SW Finland. Turun yliopiston julkaisuja series B, part 312. University of Turku, Turku

Asplund H (2011) Early Bronze Age cairn dates from burned bone. In: Harjula J, Helamaa M, Haarala J (eds) Times, things and places. 36 essays for Jussi-Pekka Taavitsainen. Juhlatoimikunta, Turku, pp 42–59

Asplund H, Moisio J, Salomaa S, Bläuer A (2019) Digging deeper into an Iron Age cairn – rethinking Roismala Ristimäki in Sastamala. Finland Fennosc Archaeol XXXVI:83–104

Bell C (1992) Ritual theory, ritual practice. Oxford University Press, New York

Bläuer A (2017) Myöhäisrautakauden ja keskiajan koti- ja riistaeläimet sekä maatiaisrodut. In: Lesell K, Meriluoto M, Raninen S (eds) Tursiannotko. Tutkimuksia hämäläiskylästä viikinkiajalta keskiajalle. Tampereen museoiden julkaisuja 148. Tampereen museot, Tampere pp 93-103

Bläuer A, Kantanen J (2013) Transition from hunting to animal husbandry in Southern, Western and Eastern Finland: new dated osteological evidence. J Archaeol Sci 40:1646–1666

Bläuer A, Korkeakoski-Väisänen K, Arppe L, Kantanen J (2013) Bronze Age cattle teeth and cremations from a monumental burial cairn in Selkäkangas, Finland: new radiocarbon-dates and isotopic analysis. Estonian J Archaeol 17(1):3–23

Bläuer A, Harjula J, Helamaa M, Lehto H, Uotila K (2019) Zooarchaeological evidence of large-scale cattle metapodial processing in the 18th century in the small town of Rauma. Finland Post Medieval Archaeol 53:172–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00794236.2019.1654737

Broderick LG (2012) Ritualisation (or the four fully articulated ungulates of the apocalypse). In: Pluskowski A (ed) The ritual killing and burial of animals. European Perspectives. Oxbow books, Oxford, pp 22–32

Bull G, Payne S (1982) Tooth eruption and epiphysial fusion in pigs and wild boar. In: Wilson B, Grigson C, Payne S (eds) Ageing and sexing animal bones from archaeological sites. BAR British Series 109. BAR publishing, Oxford, pp 55–71

Carlie A (2004) Forntida byggnadskult. Tradition och regionalitet i södra Skandinavien. Arkeologiska undersökningar, Skrifter No. 57. Riksantikvarieämbetet, Stockholm

Deckwirth V (2008) Tutkimuksia Suomen rannikon kulttuuripiirin varhaismetallikauden karjataloudesta eräiden asuinpaikkojen arkeo-osteologisen aineiston ja vertailualueiden tietojen valossa. Master’s thesis, Department of Archaeology, University of Helsinki

Fischer R, Luoto J (1983) Paimio Spurila. Koekaivausraportti. Rautakautinen polttokenttäkalmisto15.7.-15.8. 1982. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Formisto T (1996) Osteological material. In: Purhonen P (ed) Vainionmäki- a Merovingian period cemetery in Laitila, Finland. Helsinki, National Board of Antiquities, pp 81–87

Frog (2017) Myöhäisrautakautinen uskonto ja mytologia Suomessa. In: Lesell K, Meriluoto M, Raninen S (eds) Tursiannotko. Tutkimuksia hämäläiskylästä viikinkiajalta keskiajalle. Tampereen museoiden julkaisuja 148. Tampereen museot, Tampere, pp 105–126

Gaastra JS (2017) Animal remains from ritual sites: a cautionary tale from the eastern Adriatic. Int J Osteoarchaeol 28:18–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.2627

Gifford-Gonzalez D (2018) An introduction to Zooarchaeology. Springer, Cham

Grant A (1982) The use of tooth wear as a guide to the age of domestic ungulates. In: Wilson B, Grigson C, Payne S (eds) Ageing and sexing animal bones from archaeological sites. BAR British Series 109. BAR publishing, Oxford, pp 91–108

Grimes RL (2014) The craft of ritual studies. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hammer Ø (2020) PAST: paleontological statistics. Version 4.01. http://folk.uio.no/ohammer/past/index.Html (accessed March 2020)

Hårding B (2002) Människan och djuren om dagligt liv och begravningsritualer under järnåldern. In: Viklund K, Gullberg K (eds) Från Romartid till Vikingatid. Acta Antiqua Ostrobotniensia. Studia Archaeologica Universitatis Umensis, vol 15. Umeå University, Umeå, pp 213–222

Hill JD (1995) Ritual and rubbish in the Iron Age of Wessex. BAR British archaeological report series 242. BAR publishing, Oxford

Holmblad P (2013) Luolamiehistä talonpojiksi. Pohjanmaan muinaisuus sanoin ja kuvin. Scriptum, Vaasa

Hukantaival S (2016) “For a witch cannot cross such a threshold!” building concealment traditions in Finland c. 1200–1950. Archaeologia Medii Aevi Finlandiae XXIII. SKAS, Helsinki

Hukantaival S, Bläuer A (2017) Ritual deposition of animals in late Iron age Finland: a case-study of the Mulli settlement site in Raisio. Estonian J Archaeol 21(2):161–185

Insoll T (2004) Archaeology, ritual, religion. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, London

Kivikoski E (1969) Esihistoriallinen aika. In: Laitilan historia 1. Laitilan kunnan ja seurakunnan asettama historiatoimikunta, Laitila

Koivisto L (1988) Nokian Viikin rautakautisen kumpukalmiston kaivaus 1987. Kaivausraportti. Excavation report, University of Turku, archives of the Department of Archaeology

Koli L (1969) Osteologinen raportti (määritykset Elaine Anderson, Olavi Kalela, Bjorn Kurtén ja Lauri Koli). In: Sarkamo J Tyrväntö Retulansaari. Kaivauskertomus. Excavation report. Archives of NBA, Finland

Kotivuori H (1992) Dwelling-site finds from the Middle Iron Age fieldwork at Kalaschabrannan in Maalahti, southern Ostrobothnia 1987-1989. Fennosc Archaeol IX:57–74

Krohn K (1915) Suomalaisten runojen uskonto. Suomen suvun uskonnot 1. SKS, Helsinki

Kunen JL, Galindo MJ, Chase E (2002) Pits and bones: identifying Maya ritual behavior in the archaeological record. Anc Mesoam. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536102132032

Lahtinen M, Oinonen M, Tallavaara M, Walker James WP, Rowley-Conwy P (2017) The advance of cultivation at its northern European limit: process or event? Holocene 27:427–438

Lehtosalo P-L (1964) Kertomus kaivauksesta, jonka hum. kand. Pirkko-Liisa Lehtosalo suoritti kesäkuussa 1962 ja elokuussa 1963 Laitilan pitäjän Palttilan kylässä Simo Pohjalaisen omistaman talon pihamaalla. Excavation report, Finnish Heritage Agency archives

Lempiäinen-Avci M (2017) Elämää Pirkanmaalla rautakaudella-ruokaa ja rohtoa. In: Lesell K, Meriluoto M, Raninen S (eds) Tursiannotko. Tutkimuksia hämäläiskylästä viikinkiajalta keskiajalle. Tampereen museoiden julkaisuja 148. Tampereen museot, Tampere, pp 79–90

Lentacker A, Ervynck A, Van Neer W (2004) Gastronomy or religion? The animal remains from the Mithraeum at Iienen (Belgium). In: O’Day SJ, Van Neer W, Ervynck A (eds) Behaviour behind bones: the Zooarchaeology of ritual, religion, status and identity. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp 77–94

Lepokorpi N (1976) Vammala Kalliala. Kertomus kummun numero 1 tutkimisesta 10.6.-28.6. 1974. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Luho V (1953) Kertomus Tutkimuksista Tyrvännön Retulansaaren rautakautisessa kalmistossa toukokuussa v . 1953. Excavation report, Finnish Heritage Agency archives

Luoto J (1985) Archaeological excavations at Spurila 1982-1985. Iskos 5:451–459

Luoto J, Pärssinen M, Seppä-Heikka M (1983) Grain impressions in ceramics from Ristimäki, Vammala. Finland Finskt Mus 1981:5–33

Lyman RL (1994) Vertebrate Taphonomy. Cambridge manuals in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lyman RL (2018) Observations on the history of zooarchaeological quantitative units: why NISP, then MNI, then NISP again? J Archaeol Sci Rep 18:43–50

Lyman RL, Ames KM (2007) On the use of species-area curves to detect the effects of sample size. J Archaeol Sci 34:1985–1990

Macheridis S (2017) Symbolic connotations of animals at early middle Helladic Asine. Opuscula 10:128–152

Magnell O (2012) Sacred cows or old beasts? A Taphonomic approach to studying ritual killing with an example from Iron Age Uppåkra, Sweden. In: Pluskowski A (ed) The ritual killing and burial of animals. European perspectives. Oxbow books, Oxford, pp 195–19l

Mäntylä-Asplund S, Storå J (2010) On the archaeology and osteology of the Rikala cremation cemetery in Salo. SW-Finland Fennosc Archaeol XXVII:53–68

Marjakorpi T (1910) Vanha uhritapa Heinolan pitäjästä. Kotiseutu 4:59–60

Merrifield R (1988) The archaeology of ritual and magic. New Amsterdam Books, New York

Morris J (2012) Animal ‘ritual’ killing: from remains to meanings. In: Pluskowski A (ed) The ritual killing and burial of animals. European Perspectives. Oxbow books, Oxford, pp 8–21

Muhonen T (2008) Uhri ja röykkiö- rautakauden uhriröykkiöt tutkimushistorian, kansanperinteen ja arkeologisen aineiston valossa. Pro Gradu-thesis, Department of Archaeology, University of Turku

Muhonen T (2009) Something old, something new: excursions into Finnish sacrificial cairns. Temenos Nord J Comp Relig 44(2):293–346

Nurminen T (1990) Nokia Haapaniemi, Tapanila. Kaivausraportti. Rautakautisen muinaisjäännöksen tutkimuskaivaukset 5.7.-28.7. 1989. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

O’Connor TP (2003) The analysis of urban animal bone assemblages: a handbook for archaeologist. The archaeology of York. Principles and methods 19/2. Council for British Archaeology, York

Pietikäinen T (1989) Nokia Haapaniemi, Huvilaniemi, Pääskylä. Kaivausraportti. Rautakautisen muinaisjäännöksen kaivaus ajalla 23.6.-5.8.1988. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Pihlman S (1999) Kuolema arkeologisena ilmiönä- yleistyksiä esihistoriasta. ABOA Turku Provincian Museum yearbook 59(60):62–70

Raike E, Seppälä S-L (2005) Naarankalmanmäki. An Iron Age complex in Lempäälä, Southern Finland. Fennosc Archaeol XXII, 43-78

Rajala U (1991) Nokia, Keho, Pappila. Kertomus rautakautisen hautaraunion puolikkaan tutkimuskaivauksista 3 .6. - 26.7.1991. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Raninen S (2010) Sodankäynti ja soturit rautakaudella. In: Klemettilä H (ed) Suomalainen sotilas 3: Muinaisurhosta nihtiin. Hämeenlinna, Weilin & Göös, pp 46–79

Raninen S (2017) Pirkkalan Tursiannotkon ja Lähiseudun asutus myöhäisrautakaudella (800–1200). In: Lesell K, Meriluoto M, Raninen S (eds) Tursiannotko. Tutkimuksia hämäläiskylästä viikinkiajalta keskiajalle. Tampereen museoiden julkaisuja 148. Tampereen museot, Tampere, pp 11–29

Raninen S, Wessman A (2014) Finland as a part of the ‘Viking world’. In: Ahola J, Frog, Tolley C (eds) Fibula, Fabula, fact. The Viking Age in Finland. Studia Fennica Historica 18. SKS, Helsinki, pp 327–346

Raninen S, Wessman A (2015) Rautakausi. In: Haggrén G, Halinen P, Lavento M, Raninen S, Wessman A (eds) Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Suomen esi- ja varhaishistoria kivikaudelta keskiajalle. Gaudeamus Oy, Helsinki, pp 215–365

Renvall E (1987) Kaivauskertomus Nokia Viikin kumpukalmistokaivauksista 1.7. – 8.8. 1986. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Rinne J (1906) Nokia, Pirkkala, Keho tutkimuskaivaus 1905. Excavation report, Finnish Heritage Agency archives

Russell N (2012) Social Zooarchaeology. Humans and animals in prehistory. Cambridge University Press, New York

Salo U (2004) Sastamalan historia 1,1. Esihistoria. Sastamalan historiatoimikunta, Sastamala

Sarasmo E (1959) Kertomus kaivauksesta, jonka Hämeen Museon hoitaja, maisteri Esko Sarasmo suoritti Pälkäneen Epaalan kylän Hyllin talon maalla Muinaistieteellisen Toimikunnan varoilla ja valtuuttamana 1–29/6 1955. Excavation report, Finnish Heritage Agency archives

Sarkamo J (1970) Retulansaaren uhriröykkiö. Suomen Museo 77:35–47

Sarkamo J (1984) Retulansaaren “uhriröykkiö”. In: Suomen historia 1. WSOY, Espoo p 308

Sarvas A (1976) Hattula (Tyrväntö) Retulansaari Myllymäki. Kumpare n:o 152. Excavation report, Finnish heritage agency archives

Sarvas A (1977) Hattula Retulansaari Myllymäki. Kumpare n:o 152:n kaivaus. Excavation report, Finnish heritage agency archives

Schultz EL, Schultz HP (1992) Hämeenlinna Varikkoniemi – eine späteisenzeitliche-frühmittelalterliche Kernsiedlung in Häme. Die Ausgrabungen 1986–1990. Suomen Museo 99:41–85

Seppälä SL (1998) Hämeenlinna Kirstula Riihimäki. Rautakautisen polttokenttäkalmiston ja mahdollisen asuinpaikan kaivaus 12.5. - 4. 7.1997. Excavation report, Finnish Heritage Agency archives

Sipilä J (1983) Vammala Heinoo, Karkun vanha kirkko ja Kirkkovainionmäki. Kaivausraportti. Rautakautisen maan- ja kivansekaisen röykkiön kaivaus 22.07.-06.08.1982. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Sipilä J (1984) Vammala (ent. Karkku) Heinoo, Kirkkoniemi. Kaivausraportti. Rautakautisen maan- ja kivensekaisen röykkiön kaivaus 27.6.-30.6. 1983. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Sipilä M (1995) Nokia Keho, Pappila. Koekaivaus- ja kaivausraportti. Kertomus rautakautisen kalmiston koekaivauksesta ja kaivauksesta 6.6.-29.7.1994. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Sipilä M (1996) Nokia Keho, Pappila. Kaivausraportti. Kertomus rautakautisen kalmiston kaivauksesta 26.6.-28.7.1995. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Snoek J (2006) Defining ‘rituals’. In: Kreinath J, Snoek J, Stausberg M (eds) Theorizing rituals: issues, topics, approaches, concepts. Brill, Leiden, pp 4–14

Söderholm N (1998) Hämeenlinna, Kirstula, Riihimäki (KM 30304:). Analysis av ben. In: Seppälä, S.-L. 1998. Hämeenlinna Kirstula Riihimäki. Rautakautisen polttokenttäkalmiston ja mahdollisen asuinpaikan kaivaus 12.5. - 4. 7.1997. Excavation report, Finnish Heritage Agency archives

Spoof L (1990) Nokia, Keho, Pappila. Rautakautisen hautaraunion (Osa) tutkimuskaivaus 23.7.-10.8.1990. Excavation report, University of Turku, archives of the department of archaeology

Spoof L (1991) Nokia Haapaniemi, Tapanila. Kaivausraportti. Rautakautisen muinaisjäännöksen tutkimuskaivaus 18.6. – 20.7. 1990. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Taavitsainen J-P (1992) Cemeteries or refuse heaps? Archaeological formation processes and the interpretation of sites and antiquities. Suomen Museo 1991:5–14

Taavitsainen JP, Vilkuna J, Forssell H (2007) Suojoki at Keuruu : a mid 14th-century site of the wilderness culture in the light of settlement historical processes in Central Finland. Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae 346. Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, Helsinki

Talve I (1997) Finnish folk culture. Studia Fennica Ethnologica 4. SKS, Helsinki

Tourunen A (2011) Burnt, fragmented and mixed: identification and interpretation of domestic animal bones in Finnish burnt bone assemblages. Fennosc Archaeol XXVIII: 57-69

Tupala U (1994) Nokia, Keho, Pappila. Kertomus rautakautisen hautaraunion puolikkaan tutkimuskaivauksista 7.6. - 16.7. 1993. Excavation report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Uino P (1986) Iron Age Studies in Salo. I-II. Suomen muinaismuistoyhdistyksen aikakauskirja 89:1. Suomen muinaismuistoyhdistys, Helsinki

Väänänen E (1965) Laitila Palttila Kylämäki. Kalmiston kaivaus. Excavation report, Finnish Heritage Agency archives

Vormisto T (1985) Osteologisk bearbetning av benmaterial framgrävt av den arkeologiska institutionen vid Åbo Universitet 1975-1983. Karhunhammas 9:135–177

Vormisto T (1991) Nokia Viik. Luuanalyysi. Osteological report, University of Turku, Archives of the Department of Archaeology

Vuorinen JM (2009) Rakennukset ja rakentajat Raision Ihalassa rautakauden lopulla ja varhaisella keskiajalla, Annales Universitatis Turkuensis C 281. University of Turku, Turku

Waronen M (1898) Vainajainpalvelus muinaisilla suomalaisilla. SKS, Helsinki

Wessman A (2010) Death, destruction and commemoration: tracing ritual activities in Finnish Late Iron Age cemeteries (AD 550-1150). Iskos 18. Finnish Antiquarian Society, Helsinki

Wickholm A (2008) Reuse in Finnish cremation cemeteries under level ground – examples of collective memory. In: Fahlander F, Oestigaard T (eds) The materiality of death – bodies, burials, believes. BAR international series 1768. BAR publishing Oxford, pp 89–97

Wulf C (2006) Praxis. In: Kreinath J, Snoek J, Stausberg M (eds) Theorizing rituals: issues, topics, approaches, concepts. Brill, Leiden, pp 395–412

Yeshurun R, Bar-Oz G, Kaufman D, Weinstein-Evron M (2014) Purpose, permanence, and perception of 14,000-year-old architecture. Curr Anthropol 55:591–618. https://doi.org/10.1086/678275

Acknowledgements

Jussi Moisio and Visa Immonen helped with dating finds, Jussi Kinnunen with the p-XRF of the ring and Harri Bläuer with graphs. Henrik Asplund, Sonja Hukantaival, Tom Janes and Georges Kazan made valuable comments on the manuscript. Juha Kantanen from the Animal Genetic Resources Programme (LUKE) assisted with the funding of the radiocarbon dates.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Turku (UTU) including Turku University Central Hospital. This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (grant number SA286499).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he/she has no conflict of interests.

Code availability (software application or custom code)

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights

• Animal remains from twelve Finnish Iron Age sites were investigated.

• Radiocarbon dating indicates that the context of the faunal remains deposit was usually an unused cemetery.

• Zooarchaeological analysis revealed selective ritual deposition of horses and cattle remains.

• Deposits include also general domestic-type waste.

Electronic supplementary material

Online Resource 1

(XLS 45 kb)

Online Resource 2

(XLSX 21 kb)

Online Resource 3

(XLSX 11 kb)

Online Resource 4

(XLSX 15 kb)

Online Resource 5

(XLSX 14 kb)

Online Resource 6

(XLSX 14 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bläuer, A. Animal bones in old graves: a zooarchaeological and contextual study on faunal remains and new dated evidence for the ritual re-use of old cemetery sites in Southern and Western Finland. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 12, 206 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-020-01165-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-020-01165-4