Abstract

Background

Recent decades have shown a rapid increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Chinese children based on several national surveys. Restrictions due to the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak have worsened its epidemiology. This review updates the trends in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Chinese children and adolescents and analyzes the underlying reasons to provide evidence for better policy making.

Methods

Studies published in English and Chinese were retrieved from PubMed, Google Scholar, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang.

Results

The prevalence of overweight and obesity has been increasing for decades and varies with age, sex and geography but is more pronounced in primary school students. The increase in obesity in boys appeared to be slower, whereas that in girls showed a declining trend. The northern areas of China have persistently maintained the highest levels of obesity with a stable trend in recent years. Meanwhile, the prevalence in eastern regions has dramatically increased. Notably, the overall prevalence of obesity in children has shown a stabilizing trend in recent years. However, the occurrence of obesity-related metabolic diseases increased. The effect of migrants floating into east-coast cities should not be neglected.

Conclusions

The high prevalence of overweight and obesity among Chinese children and adolescents persists but with varying patterns. Obesity-related metabolic diseases occur more frequently despite a stable trend of obesity. Multiple factors are responsible for the changing prevalence. Thus, comprehensive and flexible policies are needed to effectively manage and prevent the burden of obesity and its related complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, China has experienced rapid economic growth and urbanization, which is associated with an increase in obesity and a decrease in stunting and thinness among Chinese children [1,2,3,4]. There has been a general increasing trend of obesity in Chinese children and adolescents. In particular, the prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents aged 7–18 years was 0.1% in 1985 and increased to 7.3% in 2014 according to the Working Group on Obesity in China for diagnosing obesity [5] and 6.4% according to World Health Organization standards [3]. Consequently, obesity has raised concern owing to its threat to children’s health from other associated diseases, such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases (NAFLD) [6,7,8,9]. Additionally, obesity is an impactful factor of precocious puberty among children and adolescents [10]. As obese children are more likely to maintain obese phenotypes in later life [11], timely monitoring of the status of obesity in children and adolescents is crucial.

Several national surveys have been conducted to achieve dynamic surveillance of children’s obesity and overweight (Table 1). The Chinese National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health (CNSSCH) was composed of seven cross-sectional surveys and conducted between 1985 and 2014. The China National Nutrition Survey (CNNS) was composed of five cross-sectional surveys and conducted between 1959 and 2012. The children and adolescents included in the CNSSCH and CNNS were from all subnational provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities in mainland China. Meanwhile, the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) was composed of ten cross-sectional surveys and conducted between 1989 and 2015. This survey selected 15 regions in Chinese mainland with some regions included in later periods. All three national surveys utilized a multistage stratified clustering sampling method for participant recruitment. Despite the addition of the first cycle (2015–2019) of the China Chronic Disease and Nutrition Surveillance survey, which combined the CNNS and China Chronic Disease and Risk Factor Surveillance (CCDRFS), data on recent health surveillance among children and adolescents remain limited.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has had a considerable impact on obesity [29]. An increased prevalence of obesity among Chinese youth during the COVID-19 pandemic has been reported [30,31,32,33,34]. In this review, we comprehensively summarize the national surveys and latest studies on the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Chinese children and adolescents and update the pattern in relation to age, sex and geography in recent years. After discussing the possible reasons for the changes, we outline the measures taken by the Chinese government and institutions for better management of obesity and overweight in the young generation. Finally, we appeal for a cooperative network among governments, families, schools, and health institutions.

Methods

Using various combinations of the following search terms: “prevalence”, “obesity”, “overweight”, “children”, “adolescents”, “national surveys”, “risk factors”, “complications”, “policy”, “Chinese”, and “China”, we searched PubMed, Google Scholar, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang for original articles and reviews published in English and Chinese between January 2001 and December 2022. We selected national survey-related literatures by reviewing their title, abstract and full text. Subsequently, the reference lists of the selected papers were reviewed. We excluded studies on single regions. Additionally, we used the search engine Baidu and the official websites of governments for related policies and principles.

Results

Trends of obesity and overweight in the past decades in China

Several national survey-based studies have consistently reported the increasing trend of obesity and overweight among Chinese children and adolescents over the last three decades. According to CNSSCH data, the mean body mass index (BMI) of children and adolescents aged 7–18 years increased from 17.0 kg/m2 in 1985 to 17.5 kg/m2 in 1995, 18.2 kg/m2 in 2005, and 19.0 kg/m2 in 2014 [3]. The prevalence of overweight and obesity was 1.1% and 0.1% in 1985 and 12.1% and 7.3% in 2014, respectively [3, 5], consistent with the reports from the CNSSCH in different time periods [15, 17]. The CNNS and CHNS also revealed similar trends of increased BMI, overweight, and obesity among children and adolescents over the past decades [20, 21, 23, 24, 26]. Studies have been conducted to update these statistics in younger generations for better prevention and management (Table 1).

Changes by age

For children aged < 6 years, the prevalence of overweight and obesity increased from 2.3% and 1.6% in 1992 to 3.4% and 2.0% in 2002 and 8.4% and 3.1% in 2010–2012, respectively [24, 27]. However, in the China Chronic Disease and Nutrition Surveillance survey (2015–2019), which combined the CNNS and CCDRFS, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in this age group was 6.8% and 3.6%, respectively [35], showing a decreased trend for the prevalence of overweight in comparison with that in 2012. Separately, Gao et al. examined national surveys and found a similar decrease in the prevalence of both overweight and obesity in preschool children [36].

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in 6–18-year-old participants increased as reported by national surveys [3, 5, 15, 20]. In one CHNS study, the prevalence of overweight increased from 6.5% to 16.1% in children aged 6–11 years and from 3.3% to 6.2% in children aged 12–18 years from 1991 to 2004 [20]. Based on CHSSCH surveys, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in 2010 was 17.14% in primary school students aged 7–12 years, followed by 13.11% in junior school students aged 13–15 years and 10.88% in high school students aged 16–18 years [15]. The values for these three populations increased to 22.5%, 17.3%, and 15.4% in 2014 [5]. However, a later CHNS-based study found that the prevalence of overweight and obesity was stable in children aged 7–11 and 12–18 years from 2011 to 2015 [22]. The participants in this study were from 12 provinces, with 1458 individuals included in 2011 and 1084 in 2015, which is considerably lower than that in CHSSCH-based studies during the same study period (Table 1). Additionally, the geographical distribution of the participants is not comparable; 997 children were from the southern area, which is twice as many as those from the northern areas (n = 461). Consequently, this may induce bias during analysis. Another study reported a stable and slight downward trend of overweight and obesity among children aged 3–19 years [37]. Since over half of the children in this study were aged 3–6 years, it is difficult to reflect the real trend at all ages.

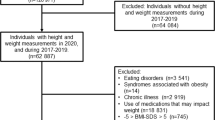

The recent Prevalence and Risk Factors for Obesity and Diabetes in Youth (PRODY) study, which included over 200,000 participants in 2017–2019, reported the highest prevalence of obesity in children aged 8–13 years [12]. Furthermore, this study compared data from two national multicenter surveys conducted from July 2009 to July 2010 and July 2017 to July 2019 [13]. Overall, 14,597 pairs of children and adolescents aged 6–15 years were recruited from four provinces or cities representing three main regions in northern, southern, and eastern China. Interestingly, the PRODY study found a continuously increasing trend of overweight among boys aged 6–14 years, with a pronounced increase at the age of 8–11 years. Among girls aged 6–10 years, there was no significant change in the prevalence of overweight or obesity, and their BMI standard deviation score (SDS) decreased from 2009 to 2019. The BMI SDS and the prevalence of overweight and obesity increased slightly but not significantly for girls aged 11–14 years [13]. Collectively, the increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity for primary school students (around 7–12 years old) merits sufficient consideration, although a stabilized trend has emerged among Chinese youth.

Changes by sex

The prevalence of overweight and obesity is higher in boys than in girls [5, 15, 38]. National surveys confirmed these trends in different time periods, with great disparities between boys and girls, irrespective of age, location, and economic status [5, 14, 16, 18, 39]. However, the PRODY study found a higher obesity prevalence in boys than in girls only in eastern and northern China in 2017–2019 [12]. By comparing data from 2009 to 2019, the PRODY study reported an increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity in boys by 2.5% and 1.8%, respectively, with lower average annual increases in comparison with 2010–2014 [2, 5]. Obesity prevalence in girls decreased by 0.9%, whereas overweight prevalence increased by 1.5% in the same decade, with a lower annual increase compared with 2010–2014 [2]. Furthermore, the overall rate of overweight and obesity in girls was not affected [13]. A meta-analysis also reported a declining trend of overweight in young people [40]. The rising trends of overweight in boys and girls observed since 1991 peaked in 2006–2010 (prevalence of 16.0% and 10.3% for boys and girls, respectively), and both sexes showed declining trends in overweight (14.4% in boys and 9.1% in girls) from 2011 to 2015 [40]. Therefore, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in boys slows down and that in girls appears to be stabilized.

Changes by region (North, South, West, and East China)

There are prominent geographical disparities. According to the CNSSCH data, the northern parts of China, including Beijing, Shandong, and Tianjin, had the highest prevalence of overweight and obesity in 1985. Conversely, Guangxi and Guangdong, in the west and south, respectively, showed the lowest prevalence. The northern provinces and cities continued to have the highest prevalence in 2005 [18]. In a more recent CNSSCH study (2010–2014) and the PRODY study (2017–2019), northern China maintained a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity [12, 19]. The PRODY study revealed an increase in overweight but no significant increase in obesity across all investigated regions from 2009 to 2019 [13]. However, each area had its own pattern, as shown in Table 2. The prevalence of obesity in the northern area (Beijing and Tianjin) showed a declining trend, whereas that of overweight continued to rise. Notably, the prevalence of both overweight and obesity in the eastern area dramatically increased during that decade. A decreasing trend in overweight and a consistent trend in obesity were observed in Guangxi. Therefore, the northern area, with the largest prevalence, warrants more attention for better control and prevention of overweight and obesity, whereas the eastern areas, with its rapid increases in both overweight and obesity, should take appropriate actions to slow down or stop further progression.

Comparison of urban and rural areas

Based on national surveys in China, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among young individuals is higher in urban than in rural areas [15, 19, 40]. According to CNNS, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents aged 6–17 years was 13.2% and 8.9% in large cities; 10.6% and 7.6% in medium-sized and small cities; 8.9% and 5.6% in common villages; and 7.5% and 4.3% in poor villages, respectively [38]. Both urban and rural areas showed an upward trend. The prevalence of obesity among Chinese urban children increased from 0.2% in 1985 to 8.1% in 2010 [16]. Compared with data in 2002, young individuals in cities showed a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity in 2012. However, the increase in rural areas was twice that in cities [41]. In particular, the average annual increase in overweight and obesity among rural children exceeded that among their urban peers in 2005–2010 [5]. Data from the CNSSCH also showed a decreasing disparity in the prevalence of overweight and obesity between urban and rural areas from 2010 to 2014, surpassing the overweight and obesity prevalence among rural children in several eastern areas in 2014 [19]. Consistently, a worse situation in preschool children from rural areas was projected [36]. In contrast, Guo et al.’s meta-analysis reported a decreased prevalence of overweight and obesity in both urban and rural areas after 2010 [40]. Due to fewer studies included in Guo et al.’s calculation for urban and rural areas in this period, the decreasing trends need to be consolidated in future studies.

Obesity-related metabolic disorders among Chinese children and adolescents

Obesity is highly associated with multiple diseases, including NAFLD, metabolic syndrome and precocious puberty [9]. Although the prevalence of obesity and overweight showed a slowing or a stabilizing trend in children, the prevalence of complications of obesity continues to increase, jeopardizing the health of children and adolescents.

Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

NAFLD is a chronic liver disease characterized by excess fat deposition in the liver without other etiologies. Obesity is the largest risk factor for NAFLD, and the prevalence of NAFLD is rising along with the increase in childhood obesity [42]. The prevalence of NAFLD in American adolescents doubled in 2007–2010 compared with that in 1988–1994, from 3.9% to 10.7%. Meanwhile, the proportion of NAFLD in obese participants is higher for both sexes [43]. Similarly, the prevalence of NAFLD in Asian children increased from 4.42% before 2010 to 7.10% after 2010 [6]. Specifically, one meta-analysis indicated that the prevalence of NAFLD in Chinese children in 2000–2010 was 4.0% and increased to 7.7% in 2011–2021 [44]. Data from Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, demonstrated that the NAFLD prevalence was as high as 57.6% in enrolled obese children, with no difference between 2008–2012 and 2013–2017 [45]. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is an advanced stage of NAFLD, with apparent infiltration of immune cells and abnormal alanine aminotransferase and/or aspartate aminotransferase levels, resulting from damaged hepatocytes and subsequent abnormal liver function. Surprisingly, among children and adolescents with obesity, those who have abnormal liver function account for 60.4%, second only to acanthosis nigricans (AN) at 69.3%. Furthermore, the proportion of abnormal liver function significantly increased, from 68% in 2008–2012 to 78.6% in 2013–2017 in obese boys aged > 10 years [45]. Although not all patients who have abnormal liver function can be diagnosed with NASH, the authors emphasized the potentially damaged liver function resulting from excess fat accumulation in the liver in obese individuals. Although the increase in NAFLD in children is not fully dependent on the obesity rate, as reported by some studies [46, 47], it is critical to realize that obesity has a profound contribution to the NAFLD disease burden, and therefore, action is needed to strengthen diagnosis and intervention in clinical practice.

Obesity and metabolic syndrome

The development of obesity is accompanied by other disorders in children and adolescents, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, and abnormal glycemia. To better recognize and evaluate the outcomes of the cluster of these disorders in youth, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) proposed the definition of metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents in 2007 [48]. The Chinese Pediatrics Society published the definition of metabolic syndrome in 2012, which was fundamental for its prevention and control [49]. In a national study of 15,045 children from seven Chinese provinces, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome calculated using the IDF criteria was 2.3% [50]. The prevalence was up to 40.1% for obese children aged > 10 years [45].

Obesity due to overfeeding impedes glucose clearance by disrupting insulin signaling in the main metabolic organs, including the muscle and liver, which results in hyperglycemia [51]. Based on the criteria for diagnosing abnormal glycemia in Chinese children and adolescents [49], Wang et al. reported a remarkable increase in the incidence of abnormal glycemia from 26.5% in 2008–2012 to 39.1% in 2013–2017 in young obese boys and from 29.1% to 37.8% in older obese boys [45]. Similar to abnormal glycemia, hypertension is considered a symptom of metabolic syndrome [49]. Children with obesity are more likely to have elevated blood pressure [52,53,54,55,56]. Surprisingly, evidence showed that the incidence of hypertension in obese girls nearly doubled from 20% in 2008–2012 to 40% in 2013–2017 regardless of age [45]. The increase in hypertension in obese boys was also remarkable. This brings great challenges to dealing with hypertension and its related cardiovascular diseases, as obesity in children increases the risk of coronary heart disease in adulthood [57, 58].

AN is a visible abnormal skin manifestation on the neck or back, with high levels of pathological cell proliferation [59]. It is highly associated with insulin resistance, which usually causes hyperinsulinemia and abnormal glycemia, as well as hyperlipidemia and high blood pressure [60,61,62]. The AN prevalence in Chinese obese children is 69.3%, with a higher value in boys (71.9%) than in girls (64%) [45], which is similar to that in Iranian obese children (67.6%) [63]. Unlike the metabolic disorders mentioned above, dyslipidemia showed a distinct trend. A significant decrease in the incidence of dyslipidemia was reported after 2013 in boys with obesity [45], and a decreasing trend was also observed in all recruited girls, although it was not statistically significant.

Obesity and precocious puberty

Precocious puberty, featured by early onset (before 8 years in girls and 9 years in boys) of secondary sexual characteristics [64], emerges as an obesity-related metabolic disease. Its prevalence in China has increased, as reported by multicenter studies [65, 66]. Obesity is a high-risk factor for precocious puberty [67]. According to a regional study in China, the prevalence of precocious puberty was 11.47% in girls and 3.26% in boys and was considerably higher in overweight (27.9%) and obese (48.0%) girls than in normal-weight girls (8.7%) [68]. A recent retrospective study confirmed a strong association of obesity with precocious puberty, with more pronounced effects in girls [10], which was consistent with other reports [66, 68, 69]. A theory of bidirectional effects between obesity and precocious puberty has prevailed [67]. Chinese data supported that early puberty in girls increased the risk of obesity [70]. Therefore, the authors propose that precocious puberty is an emerging obesity-related metabolic disease due to its metabolic outcomes in addition to consequent short final adult height and psychological disorders for children [71]. Notably, the current growth charts for evaluating growth and related disorders do not consider the potential impacts of puberty on the growth and development of Chinese children and adolescents. Thus, Pu et al. published growth curves for boys and girls in different Tanner phases after a large-scale multicenter investigation in China, which are critical to accurately assess the age-specific height and weight at different Tanner stages [72].

Obesity is also a high-risk factor for other disorders, including obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome and polycystic ovary syndrome [73,74,75,76], which profoundly threaten the health of children and adolescents (Fig. 1). Great attention should be given to obesity-related metabolic disorders, particularly emerging precocious puberty.

High-risk factors for childhood obesity and obesity-related disorders and measures for disease control and prevention accordingly. The right part of the figure presents high-risk factors for obesity. The left part of the figure specifies measures taken by governments, schools, families and health institutions. Individual actions are also highlighted. The middle part summarizes obesity-related metabolic diseases. NAFLD nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, OSAHS obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome, PCOS polycystic ovary syndrome

Discussion

After having an updated picture of the prevalence of obesity and overweight among Chinese children and adolescents, it is necessary to explore possible reasons to provide appropriate policies accordingly. A bio-socio-ecological framework covering national policy, social environment, individual lifestyle, and genetic factors has been proposed to illustrate the changing prevalence [9], and a similar network applies for the Chinese population [77].

Environmental risk factors

Multiple factors contribute directly or indirectly to the high prevalence of overweight and obesity (Fig. 1). The globalization and liberalization of trade promote the availability of a wide variety and large quantities of foods [78]. According to the CNSSCH survey, China’s developing economy, accompanied by improved nutritional status, is positively correlated with children’s obesity [4]. Western-style and fast foods have flourished in China [79, 80], providing easy access to overnutrition and unhealthy food. Governmental policies can shape people’s health. The one-child policy was effective during 1979–2015, and there is evidence that single children are more likely to develop overweight or obesity than peers with siblings [81]. Additionally, national guidelines for the prevention of childhood obesity were not proposed until 2007, when the prevalence of obesity surged [82].

Migration is an emerging factor in the increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity [83, 84]. Based on the seventh population census in China, developed eastern coastal areas maintained a higher inflow migration rate in the twenty-first century [85]. Over 19 million people born in other provinces (mainly northeast and midwest areas) migrated to Zhejiang Province from 2010 to 2020, accounting for 13.54% of all migrants throughout the country [85]. Importantly, family migration has prevailed recently, and thus, more children migrate with their parents into inflow places. The number of children in primary schools in eastern areas increased dramatically from 10% in 2010 to 40% in 2019 [86]. It is presumed that these young migrants are risk factors leading to the rapidly increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in eastern areas of China, as migrants have been reported to have a higher ratio of overweight and obesity than the local population [84, 87]. Nevertheless, large-scale investigations on the influence of migrant children should be considered considering great disparities in culture and lifestyle between eastern coastal areas and outflow areas.

Home- and school-related environmental factors are involved in the increasing prevalence of obesity and overweight among children, particularly those in primary schools. High academic burden from excess homework [88] and the sale of carbonated drinks in schools and nearby convenience stores are highly associated with increased obesity [89, 90]. School activities, such as sport meetings, are also associated with BMI [90]. Mothers who eat out more frequently were reported to give more pocket money to their children, and increased pocket money facilitates excess energy intake by children [91, 92]. From a view of Chinese cultural norms, excess body fat is thought to be a sign of healthy growth [25], particularly in younger children and boys [93], and the misperception of children’s body size by their caregivers, including grandparents and parents, contributes to children’s overweight and obesity [94, 95].

Individual risk factors

With the transition from the traditional Chinese to a Western diet [38, 96,97,98], personal eating habits have become a direct contributor to increased obesity and overweight (Fig. 1). Processed foods are directly associated with increased BMI [99]. In a cross-sectional study, more than half of the young participants consumed sugar-sweetened beverages, and those consuming higher amounts were more likely to have abdominal obesity [100]. Children’s eating-out behaviors are also associated with obesity [92]. Inadequate sleep, physical inactivity and screen viewing time outside schools, which are closely linked to energy balancing, are strong contributors to child obesity [88, 101, 102]. In China, pregnant women have diets enriched in various nutrients and remain sedentary, which are considered beneficial for gestation [103]. However, maternal overnutrition and gestational weight gain are likely to be responsible for macrosomia [104, 105].

In this review, we highlight a recent stabilized trend of overweight and obesity among Chinese children and adolescents, which is consistent with studies from other countries [106, 107]. A flattened mean BMI is reported despite the increase in the global age-standardized prevalence of obesity from 0.7% and 0.9% in 1975 to 5.6% and 7.8% in 2016 for girls and boys, respectively [108]. A series of studies relying on national surveys showed that the prevalence of obesity in American children at younger ages (< 11 years) stabilized or even declined, whereas it continued to increase among older children and adolescents aged 12–19 years [109,110,111]. However, there is contradictory evidence reporting no decline in the prevalence of obesity in children aged 2–19 years and a significant increase in children aged 2–5 years [112]. A more recent cohort study reported a worse obesity incidence than those in the past 12 years [113], highlighting the importance of national longitudinal design in monitoring the prevalence of obesity and overweight in children and adolescents. The slowing of the increase in BMI and obesity prevalence was also reported in Chinese adults according to the CCDRFS program [114]. More surveillance is needed to monitor and consolidate new trends in the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Chinese youths and adults in the future.

It would be fascinating to investigate the causes of the recent slight reversal of the long-term increases in overweight and obesity in Chinese children and adolescents. Government policies are the major tools in managing the burden caused by overweight and obesity in China. Since 2000, many official policies have been implemented, which highlight the importance of exercise, obesity surveillance, and healthy food intake, as reviewed elsewhere [77]. The protective effects of breastfeeding against overweight and obesity in younger children have been reported [115,116,117], and both breastfeeding rate and duration have increased rapidly in the past decade [118, 119]. A possible reason for the declining trend of obesity or overweight in girls is the self-evaluation of their body image. A number of girls perceive themselves as overweight, which leads to deliberate actions to lose weight, although many of them actually have normal weight [120, 121].

The problem remains challenging owing to a large percentage of obesity and overweight in the Chinese population, which can easily worsen in the future. According to Wang et al., 15.6% of preschool children and 31.8% of school-age children are projected to be overweight or obese in 2030 [77]. In addition, obesity-related metabolic disorders among Chinese children and adolescents are expected to increase the disease burden on the healthcare system. The intensification of the obesity epidemic by COVID-19 must not be ignored. A review article evaluated the lifestyle of the younger generation worldwide and concluded that COVID-19 restrictions led to unhealthy food choices, increased food intake, and reduced outdoor physical activities [122]. Consistently, the COVID-19 lockdown increased the prevalence of obesity and overweight in Chinese children at preschool and school age by changing their lifestyle, such as reducing physical activities and increasing screen-viewing time [31,32,33,34]. Undoubtedly, since the beginning of 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak has induced a sharp increase in the prevalence of obesity and overweight [37]. Thus, urgent precautions are imperative for evaluating the long-term effects of COVID-19 on the prevalence and management of obesity among Chinese children and adolescents.

Conclusions and strategies for the prevention and management of childhood obesity

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among Chinese children and adolescents has been increasing, as reported by CNSSCH-, CHNS-, and CNNS-based studies (Table 1). Children in primary schools need lifestyle management, as they have a higher prevalence than older children and adolescents [5, 13 15]. The prevalence in boys gradually slows down, and that in girls appears to decrease [13]. Although a persistently higher prevalence of obesity exists in northern areas, the trend is not significant in recent years; meanwhile, the prevalence in eastern areas is surging [13]. The increase in obesity-related complications makes it challenging to address the burden of obesity [6, 10, 44, 45, 66, 68, 123]. Additionally, COVID-19 restrictions have worsened the epidemic of obesity in Chinese children and adolescents [31,32,33,34]. These could be attributed to the factors at national and social levels (e.g., transition of nutrition) [3, 4] and migration [85, 86]. Less healthy home and school environments, as well as personal behaviors, are more direct contributors, particularly to children in primary schools. Thus, dynamic surveillance needs to continue, and appropriate measures for disease prevention and management are imperative.

Several Chinese national policies and guidelines have been implemented since 2000, aiming to improve children’s health [77]. In October 2016, the State Council published the Health China 2030 Plan, aiming to establish a comprehensive system of health promotion and services [124]. In July 2019, a national health promotion committee under the State Council was organized and issued the Healthy China Program (2019–2030) [125]. This program proposed a variety of initiatives for the advancement of Chinese health status and disease control and prevention. In this program, children in primary and middle schools are required to have physical activities inside schools for > 1 hour per day. Additionally, health education curricula are to be introduced in all schools, and child health care experts are employed in over 70% of the schools. Activities outside schools, including sleeping and screen viewing time, are discussed for school students. In October 2020, six Chinese government agencies published “The Plan of Obesity Control and Prevention in Children and Adolescents” [126]. This plan aims to reduce the prevalence of obesity according to its different epidemic levels. The respective annual increases in regions with a high, intermediate, and low prevalence are 20%, 30%, and 40% of the baseline from 2020 to 2030. Zhejiang Province, with an intermediate prevalence, merits more attention considering the rapid increase in recent years. Notably, cooperation relying on internet platforms among the government, families, schools and health institutions was encouraged for better management of body weight and promotion of healthy growth and development in children and adolescents (Fig. 1).

Reducing energy intake and increasing energy expenditure without adverse influence on children’s growth and development are effective therapies for obesity [127]. The amount of energy intake for children with normal, overweight, and obese BMI at different ages has been tailored in the Nutritional Guidelines for Weight Management of school-aged children, released by the Chinese Nutrition Society in June 2021 [128]. Children are recommended to eat a balanced diet according to their age, sex, and level of physical activity. Nutritionists can help decide energy intake for obese and overweight children aged 6–12 years, while medical doctors can evaluate the balance between weight loss and normal development for obese or overweight children aged 13–17 years, particularly those who have early puberty onset. Two national policies published in the same year specified the work of different aspects and emphasized early diagnosis and intervention [129, 130]. The effectiveness of these policies and guidelines in the control and prevention of obesity among Chinese children and adolescents needs to be assessed by scientific evidence in the future.

Data availability

All data collected or interpreted during this study are included in this manuscript.

References

Wang Y, Wang L, Qu W. New national data show alarming increase in obesity and noncommunicable chronic diseases in China. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71:149–50.

Song Y, Agardh A, Ma J, Li L, Lei Y, Stafford RS, et al. National trends in stunting, thinness and overweight among Chinese school-aged children, 1985–2014. Int J Obes. 2019;43:402–11.

Dong Y, Lau PWC, Dong B, Zou Z, Yang Y, Wen B, et al. Trends in physical fitness, growth, and nutritional status of Chinese children and adolescents: a retrospective analysis of 1.5 million students from six successive national surveys between 1985 and 2014. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3:871–80.

Dong Y, Jan C, Ma Y, Dong B, Zou Z, Yang Y, et al. Economic development and the nutritional status of Chinese school-aged children and adolescents from 1995 to 2014: an analysis of five successive national surveys. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:288–99.

Wang S, Dong YH, Wang ZH, Zou ZY, Ma J. Trends in overweight and obesity among Chinese children of 7–18 years old during 1985–2014. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2017;51:300–5 (in Chinese).

Zou ZY, Zeng J, Ren TY, Huang LJ, Wang MY, Shi YW, et al. The burden and sexual dimorphism with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Asian children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver Int. 2022;42:1969–80.

Bendor CD, Bardugo A, Pinhas-Hamiel O, Afek A, Twig G. Cardiovascular morbidity, diabetes and cancer risk among children and adolescents with severe obesity. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:79.

Di Cesare M, Sorić M, Bovet P, Miranda JJ, Bhutta Z, Stevens GA, et al. The epidemiological burden of obesity in childhood: a worldwide epidemic requiring urgent action. BMC Med. 2019;17:212.

Jebeile H, Kelly AS, O’Malley G, Baur LA. Obesity in children and adolescents: epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10:351–65.

Liu G, Guo J, Zhang X, Lu Y, Miao J, Xue H. Obesity is a risk factor for central precocious puberty: a case-control study. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21:509.

Ward ZJ, Long MW, Resch SC, Giles CM, Cradock AL, Gortmaker SL. Simulation of growth trajectories of childhood obesity into adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2145–53.

Zhang L, Chen J, Zhang J, Wu W, Huang K, Chen R, et al. Regional disparities in obesity among a heterogeneous population of Chinese children and adolescents. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2131040.

Yuan JN, Jin BH, Si ST, Yu YX, Liang L, Wang CL, et al. Changing prevalence of overweight and obesity among Chinese children aged 6–15 from 2009–2019. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2021;59:935–41 (in Chinese).

Ji CY, Cheng TO. Epidemic increase in overweight and obesity in Chinese children from 1985 to 2005. Int J Cardiol. 2009;132:1–10.

Ma J, Cai CH, Wang HJ, Dong B, Song Y, Hu PJ, et al. The trend analysis of overweight and obesity in Chinese students during 1985–2010. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2012;46:776–80 (in Chinese).

Song Y, Wang HJ, Ma J, Wang Z. Secular trends of obesity prevalence in urban Chinese children from 1985 to 2010: gender disparity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53069.

Song Y, Wang HJ, Dong B, Ma J, Wang Z, Agardh A. 25-year trends in gender disparity for obesity and overweight by using WHO and IOTF definitions among Chinese school-aged children: a multiple cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011904.

Jia P, Ma S, Qi X, Wang Y. Spatial and temporal changes in prevalence of obesity among Chinese children and adolescents, 1985–2005. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E160.

Dong Y, Ma Y, Dong B, Zou Z, Hu P, Wang Z, et al. Geographical variation and urban-rural disparity of overweight and obesity in Chinese school-aged children between 2010 and 2014: two successive national cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025559.

Zhang J, Seo DC, Kolbe L, Middlestadt S, Zhao W. Trends in overweight among school children and adolescents in seven Chinese Provinces, from 1991–2004. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5:375–82.

Cui Z, Huxley R, Wu Y, Dibley MJ. Temporal trends in overweight and obesity of children and adolescents from nine Provinces in China from 1991–2006. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5:365–74.

Zhang J, Wang H, Wang Z, Du W, Su C, Zhang J, et al. Prevalence and stabilizing trends in overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in China, 2011–2015. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:571.

Ma S, Hou D, Zhang Y, Yang L, Sun J, Zhao M, et al. Trends in abdominal obesity among Chinese children and adolescents, 1993–2015. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2021;34:163–9.

Ma GS, Li YP, Wu YF, Zhai FY, Cui ZH, Hu XQ, et al. The prevalence of body overweight and obesity and its changes among Chinese people during 1992 to 2002. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2005;39:311–5 (in Chinese).

Wu Y. Overweight and obesity in China. BMJ. 2006;333:362–3.

Li Y, Schouten EG, Hu X, Cui Z, Luan D, Ma G. Obesity prevalence and time trend among youngsters in China, 1982–2002. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17:131–7.

Yu DM, Ju LH, Zhao LY, Fang HY, Yang ZY, Guo HJ, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of oveweight and obesity in Chinese children aged 0–5 years. Chin J Epidemiol. 2018;39:710–4 (in Chinese).

Li H, Zong XN, Ji CY, Mi J. Body mass index cut-offs for overweight and obesity in Chinese children and adolescents aged 2–18 years. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2010;31:616–20 (in Chinese).

Clemmensen C, Petersen MB, Sørensen TIA. Will the COVID-19 pandemic worsen the obesity epidemic? Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:469–70.

Yang S, Guo B, Ao L, Yang C, Zhang L, Zhou J, et al. Obesity and activity patterns before and during COVID-19 lockdown among youths in China. Clin Obes. 2020;10:e12416.

Wen J, Zhu L, Ji C. Changes in weight and height among Chinese preschool children during COVID-19 school closures. Int J Obes. 2021;45:2269–73.

He Y, Luo B, Zhao L, Liao S. Influences of the COVID-19 pandemic on obesity and weight-related behaviors among Chinese children: a multi-center longitudinal study. Nutrients. 2022;14:3744.

Long X, Li XY, Jiang H, Shen LD, Zhang LF, Pu Z, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 kindergarten closure on overweight and obesity among 3- to 7-year-old children. World J Pediatr. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-022-00651-0.

Yang D, Luo C, Feng X, Qi W, Qu S, Zhou Y, et al. Changes in obesity and lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chinese adolescents: a longitudinal analysis from 2019 to 2020. Pediatr Obes. 2022;17:e12874.

The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. Press briefing for the report on Chinese residents’ chronic diseases and nutrition. 2020. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-12/24/content_5572983.htm. Accessed 24 Dec 2022.

Gao L, Wu Y, Chen S, Zhou H, Zhao L, Wang Y. Time trends and disparities in combined overweight and obesity prevalence among children in China. Nutr Bull. 2022;47:288–97.

Yang Y, Zhang M, Yu J, Pei Z, Sun C, He J, et al. Nationwide trends of pediatric obesity and BMI z-score from 2017–2021 in China: comparable findings from real-world mobile- and hospital-based data. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:859245.

Chang JL, Wang Y, Liang XF, Wu LY, Ding GQ. Chinese national nutrition and health survey (2010–2013): comprehensive summary. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press; 2016.

Wang Y, Lim H. The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2012;24:176–88.

Guo Y, Yin X, Wu H, Chai X, Yang X. Trends in overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in China from 1991 to 2015: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:4656.

Wang YF, Sun MX, Yang YX. China blue paper on obesity prevention and control. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press; 2019.

Yu EL, Schwimmer JB. Epidemiology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2021;17:196–9.

Welsh JA, Karpen S, Vos MB. Increasing prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among United States adolescents, 1988–1994 to 2007–2010. J Pediatr. 2013;162:496–500.e1.

Wang Y, Yang ZR, Chen RH. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Chinese children. Chin J Child Health Care. 2022;30:764–9 (in Chinese).

Wang J, Lin H, Chiavaroli V, Jin B, Yuan J, Huang K, et al. High prevalence of cardiometabolic comorbidities among children and adolescents with severe obesity from a large metropolitan centre (Hangzhou, China). Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:807380.

Perito ER, Ajmera V, Bass NM, Rosenthal P, Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB, et al. Association between cytokines and liver histology in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1:609–22.

Newton KP, Feldman HS, Chambers CD, Wilson L, Behling C, Clark JM, et al. Low and high birth weights are risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. J Pediatr. 2017;187:141–6.e1.

Zimmet P, Alberti G, Kaufman F, Tajima N, Silink M, Arslanian S, et al. The metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. Lancet. 2007;369:2059–61.

Subspecialty Group of Endocrinologic, Hereditary and Metabolic Diseases, The Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association; Subspecialty Group of Cardiology, The Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association; Subspecialty Groups of Child Health Care, The Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association. The definition of metabolic syndrome and prophylaxis and treatment proposal in Chinese children and adolescents. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2012;50:420–2 (in Chinese).

Zhu Y, Zheng H, Zou Z, Jing J, Ma Y, Wang H, et al. Metabolic syndrome and related factors in Chinese children and adolescents: analysis from a Chinese national study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2020;27:534–44.

Czech MP. Insulin action and resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nat Med. 2017;23:804–14.

Xu H, Hu X, Zhang Q, Du S, Fang H, Li Y, et al. The association of hypertension with obesity and metabolic abnormalities among Chinese children. Int J Hypertens. 2011;2011:987159.

Mavrakanas TA, Konsoula G, Patsonis I, Merkouris BP. Childhood obesity and elevated blood pressure in a rural population of northern Greece. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9:1150.

Cao ZQ, Zhu L, Zhang T, Wu L, Wang Y. Blood pressure and obesity among adolescents: a school-based population study in China. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:576–82.

Lo JC, Chandra M, Sinaiko A, Daniels SR, Prineas RJ, Maring B, et al. Severe obesity in children: prevalence, persistence and relation to hypertension. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2014;2014:3.

Karatzi K, Protogerou A, Rarra V, Stergiou GS. Home and office blood pressure in children and adolescents: the role of obesity. The Arsakeion School Study. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:512–20.

Meyer JF, Larsen SB, Blond K, Damsgaard CT, Bjerregaard LG, Baker JL. Associations between body mass index and height during childhood and adolescence and the risk of coronary heart disease in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22:e13276.

Baker JL, Olsen LW, Sørensen TI. Childhood body-mass index and the risk of coronary heart disease in adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2329–37.

Rafalson L, Pham TH, Willi SM, Marcus M, Jessup A, Baranowski T. The association between acanthosis nigricans and dysglycemia in an ethnically diverse group of eighth grade students. Obesity. 2013;21:E328–33.

Burguete-García AI, Ramírez Valverde AG, Espinoza-León M, Vázquez IS, Estrada Ramírez EY, Maldonado-López I, et al. Severe quantitative scale of acanthosis nigricans in neck is associated with abdominal obesity, HOMA-IR, and hyperlipidemia in obese children from Mexico City: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Res Pract. 2022;2022:2906189.

Thiagarajan S, Arun Babu T, Manivel P. Acanthosis nigricans and metabolic risk factors in obese children. Indian J Pediatr. 2020;87:162.

Maimaiti M, Xu YJ, Xu PR. Childhood benign acanthosis nigricans and metabolic abnormality. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2012;14:604–6 (in Chinese).

Sayarifard F, Sayarifard A, Allahverdi B, Ipakchi S, Moghtaderi M, Yaghmaei B. Prevalence of acanthosis nigricans and related factors in Iranian obese children. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:SC05–7.

Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. The precocious puberty clinics guide (trial). Chin J Child Health Care. 2011;19:390–2 (in Chinese).

Zhu M, Fu J, Liang L, Gong C, Xiong F, Liu G, et al. Epidemiologic study on current pubertal development in Chinese school-aged children. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2013;42:396–402 (in Chinese).

Xu XQ, Zhang JW, Chen RM, Luo JS, Chen SK, Zheng RX, et al. Relationship between body mass index and sexual development in Chinese children. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2022;60:311–6 (in Chinese).

Reinehr T, Roth CL. Is there a causal relationship between obesity and puberty? Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3:44–54.

Liu Y, Yu T, Li X, Pan D, Lai X, Chen Y, et al. Prevalence of precocious puberty among Chinese children: a school population-based study. Endocrine. 2021;72:573–81.

Chen C, Zhang Y, Sun W, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Song Y, et al. Investigating the relationship between precocious puberty and obesity: a cross-sectional study in Shanghai China. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014004.

Ma T, Li YH, Chen MM, Ma Y, Gao D, Chen L, et al. Associations between early onset of puberty and obesity types in children: based on both the cross-sectional study and cohort study. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2022;54:961–70 (in Chinese).

Subspecialty Group of Endocrinologic, Hereditary and Metabolic Diseases, the Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association; Editorial Board, Chinese Journal of Pediatrics. Expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of central precocious puberty 2022. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2023;61:16–22 (in Chinese).

Pu JQ, Zhang JW, Chen RM, Mireguli M, Luo JS, Chen SK, et al. Survey of height and weight of children and adolescents at different Tanner stages in urban China. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2021;59:1065–73 (in Chinese).

Lee JH, Cho J. Sleep and obesity. Sleep Med Clin. 2022;17:111–6.

Calcaterra V, Verduci E, Cena H, Magenes VC, Todisco CF, Tenuta E, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome in insulin-resistant adolescents with obesity: the role of nutrition therapy and food supplements as a strategy to protect fertility. Nutrients. 2021;13:1848.

Simon S, Rahat H, Carreau AM, Garcia-Reyes Y, Halbower A, Pyle L, et al. Poor sleep is related to metabolic syndrome severity in adolescents with PCOS and obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:e1827–34.

Li L, Feng Q, Ye M, He Y, Yao A, Shi K. Metabolic effect of obesity on polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;37:1036–47.

Wang Y, Zhao L, Gao L, Pan A, Xue H. Health policy and public health implications of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:446–61.

Cuevas García-Dorado S, Cornselsen L, Smith R, Walls H. Economic globalization, nutrition and health: a review of quantitative evidence. Global Health. 2019;15:15.

Popkin BM. Nutrition, agriculture and the global food system in low and middle income countries. Food Policy. 2014;47:91–6.

Wang Y, Wang L, Xue H, Qu W. A review of the growth of the fast food industry in China and its potential impact on obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:1112.

Min J, Xue H, Wang VHC, Li M, Wang Y. Are single children more likely to be overweight or obese than those with siblings? The influence of China’s one-child policy on childhood obesity. Prev Med. 2017;103:8–13.

Chen CM, Ma GS, Ji CY, Wang SL, Du SM, Li YP, et al. Guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in among school-age children and adolescents in China (trial). Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2007.

Vilar-Compte M, Bustamante AV, López-Olmedo N, Gaitán-Rossi P, Torres J, Peterson KE, et al. Migration as a determinant of childhood obesity in the United States and Latin America. Obes Rev. 2021;22(Suppl 3):e13240.

Moncho J, Martínez-García A, Trescastro-López EM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in children of immigrant origin in Spain: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1711.

Wang GX. Research on characteristics of China’s inter-provincial migration: based on the data of China’s seventh population census. Chin J Popul Sci. 2022;2–16 (in Chinese).

Guo DY. The research on the impact of school-age population changes on the allocation of compulsory education resources. Changchun: Jilin University; 2022.

He H, Zhang J, Xiu D. China’s migrant population and health. CPDS. 2019;3:53–66.

Ren H, Zhou Z, Liu WK, Wang X, Yin Z. Excessive homework, inadequate sleep, physical inactivity and screen viewing time are major contributors to high paediatric obesity. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106:120–7.

Zhou S, Cheng Y, Cheng L, Wang D, Li Q, Liu Z, et al. Association between convenience stores near schools and obesity among school-aged children in Beijing. China BMC Public Health. 2020;20:150.

Li M, Dibley MJ, Yan H. School environment factors were associated with BMI among adolescents in Xi’an City. China BMC Public Health. 2011;11:792.

Li M, Xue H, Jia P, Zhao Y, Wang Z, Xu F, et al. Pocket money, eating behaviors, and weight status among Chinese children: the childhood obesity study in China mega-cities. Prev Med. 2017;100:208–15.

Zheng J, Gao L, Xue H, Xue B, Zhao L, Wang Y, et al. Eating-out behaviors, associated factors and associations with obesity in Chinese school children: findings from the childhood obesity study in China mega-cities. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60:3003–12.

Zhang T, Cai L, Jing J, Ma L, Ma J, Chen Y. Parental perception of child weight and its association with weight-related parenting behaviours and child behaviours: a Chinese national study. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:1671–80.

Li B, Adab P, Cheng KK. The role of grandparents in childhood obesity in China-evidence from a mixed methods study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:91.

Butler ÉM, Suhag A, Hong Y, Liang L, Gong C, Xiong F, et al. Parental perceptions of obesity in school children and subsequent action. Child Obes. 2019;15:459–67.

Zhai FY, Du SF, Wang ZH, Zhang JG, Du WW, Popkin BM. Dynamics of the Chinese diet and the role of urbanicity, 1991–2011. Obes Rev. 2014;15(Suppl 1):16–26.

Wang L. Chinese national nutrition and health survey (2002): comprehensive summary. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2005.

Popkin BM. Synthesis and implications: China’s nutrition transition in the context of changes across other low- and middle-income countries. Obes Rev. 2014;15(Suppl 1):60–7.

Zhou Y, Du S, Su C, Zhang B, Wang H, Popkin BM. The food retail revolution in China and its association with diet and health. Food Policy. 2015;55:92–100.

Gui ZH, Zhu YN, Cai L, Sun FH, Ma YH, Jing J, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and risks of obesity and hypertension in Chinese children and adolescents: a national cross-sectional analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9:1302.

Dearth-Wesley T, Howard AG, Wang H, Zhang B, Popkin BM. Trends in domain-specific physical activity and sedentary behaviors among Chinese school children, 2004–2011. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14:141.

Zhu Z, Tang Y, Zhuang J, Liu Y, Wu X, Cai Y, et al. Physical activity, screen viewing time, and overweight/obesity among Chinese children and adolescents: an update from the 2017 physical activity and fitness in China-the youth study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:197.

Withers M, Kharazmi N, Lim E. Traditional beliefs and practices in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum: a review of the evidence from Asian countries. Midwifery. 2018;56:158–70.

Poston L, Caleyachetty R, Cnattingius S, Corvalán C, Uauy R, Herring S, et al. Preconceptional and maternal obesity: epidemiology and health consequences. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:1025–36.

Procter SB, Campbell CG. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: nutrition and lifestyle for a healthy pregnancy outcome. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:1099–103.

Rokholm B, Baker JL, Sørensen TIA. The levelling off of the obesity epidemic since the year 1999—a review of evidence and perspectives. Obes Rev. 2010;11:835–46.

Wabitsch M, Moss A, Kromeyer-Hauschild K. Unexpected plateauing of childhood obesity rates in developed countries. BMC Med. 2014;12:17.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627–42.

Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Martin CB, Freedman DS, Carroll MD, Gu Q, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence by race and Hispanic origin-1999-2000 to 2017–2018. JAMA. 2020;324:1208–10.

Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Hales CM, Carroll MD, Aoki Y, Freedman DS. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographics and urbanization in US children and adolescents, 2013–2016. JAMA. 2018;319:2410–8.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, Fryar CD, Kruszon-Moran D, Kit BK, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 through 2013–2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2292–9.

Skinner AC, Ravanbakht SN, Skelton JA, Perrin EM, Armstrong SC. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in US children, 1999–2016. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20173459.

Cunningham SA, Hardy ST, Jones R, Ng C, Kramer MR, Narayan KMV. Changes in the incidence of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2022;150:e2021053708.

Wang L, Zhou B, Zhao Z, Yang L, Zhang M, Jiang Y, et al. Body-mass index and obesity in urban and rural China: findings from consecutive nationally representative surveys during 2004–18. Lancet. 2021;398:53–63.

Huang H, Gao Y, Zhu N, Yuan G, Li X, Feng Y, et al. The effects of breastfeeding for four months on thinness, overweight, and obesity in children aged 3 to 6 years: a retrospective cohort study from national physical fitness surveillance of Jiangsu Province. China Nutrients. 2022;14:4154.

Li W, Yuan J, Wang L, Qiao Y, Liu E, Wang S, et al. The association between breastfeeding and childhood obesity/underweight: a population-based birth cohort study with repeated measured data. Int Breastfeed J. 2022;17:82.

Liu F, Lv D, Wang L, Feng X, Zhang R, Liu W, et al. Breastfeeding and overweight/obesity among children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22:347.

Li Q, Tian J, Xu F, Binns C. Breastfeeding in China: a review of changes in the past decade. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:8234.

Kang L, Liang J, He C, Miao L, Li X, Dai L, et al. Breastfeeding practice in China from 2013 to 2018: a study from a national dynamic follow-up surveillance. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:329.

Song L, Zhang Y, Chen T, Maitusong P, Lian X. Association of body perception and dietary weight management behaviours among children and adolescents aged 6–17 years in China: cross-sectional study using CHNS (2015). BMC Public Health. 2022;22:175.

Qin TT, Xiong HG, Yan MM, Sun T, Qian L, Yin P. Body weight misperception and weight disorders among Chinese children and adolescents: a latent class analysis. Curr Med Sci. 2019;39:852–62.

Stavridou A, Kapsali E, Panagouli E, Thirios A, Polychronis K, Bacopoulou F, et al. Obesity in children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. Children. 2021;8:135.

Zhang JX, Tian T, Wang YY, Xie W, Zhu QR, Dai Y. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among children and adolescents aged 7–17 years in Jiangsu Province, 2016–2017. Pract Prev Med. 2022;29:916–9.

State Council. Healthy China 2030 plan. 2016. http://english.www.gov.cn/news/video/2016/10/28/content_281475477055521.htm. Accessed 9 Jan 2023.

State Council. Healthy China program (2019–2030). 2019. http://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/201907/15/content_WS5d2c7b11c6d05cbd94d67a12.html. Accessed 9 Jan 2023.

National Health Commission, State Administration for Market Regulation, Ministry of Education, State Sport General Administration, Central Committee of the Communist Youth League, All-China Women’s Federation. The plan of obesity control and prevention in children and adolescents. 2020. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-10/24/content_5553848.htm. Accessed 9 Jan 2023.

Subspecialty Group of Endocrinologic, Hereditary and Metabolic Diseases, the Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association; Subspecialty Group of Child Health Care, the Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association; Subspecialty Group of Clinical Nutrition, the Society of Pediarics, Chinese Medical Association; Editorial Board, Chinese Journal of Pediatrics. Expert consensus on diagnosis, assessment, and management of obesity in Chinese children. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2022;60:507–15 (in Chinese).

Chinese Nutrition Society. Nutritional guidelines for weight management of school-aged children. 2021. https://www.cnsoc.org/otherNotice/762100200.html. Accessed 9 Jan 2023.

National Working Committee on Children and Women under State Council. Outline of China’s children’s development (2021–2030). 2021. https://www.nwccw.gov.cn/2021-09/27/content_295436.htm. Accessed 12 Dec 2022.

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Healthy children program promotion (2021–2025). 2021. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2021-11/05/content_5649019.htm. Accessed 12 Dec 2022.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2021YFC2701901 and 2016YFC1305301), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81570759 and 81270938), and Zhejiang Provincial Key Disciplines of Medicine (Innovation Discipline, No. 11-CX24). Jin-Ling Wang et al. were acknowledged for permission of authorizing the data.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2021YFC2701901 and 2016YFC1305301), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81570759 and 81270938), and Zhejiang Provincial Key Disciplines of Medicine (Innovation Discipline, No. 11-CX24).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HY contributed to searching of the literatures, drafting, reviewing and revising of the manuscript. UR and WJB contributed to reviewing and revising of the manuscript. FJF contributed to conceptualization, supervision, reviewing and revising for important intellectual content, and funding acquisition. All authors approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

No financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. Author Jun-Fen Fu is a member of the Editorial Board for World Journal of Pediatrics. The paper was handled by the other Editor and has undergone rigorous peer review process. Author Jun-Fen Fu was not involved in the journal's review of, or decisions related to, this manuscript. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, Y., Ullah, R., Wang, JB. et al. Trends of obesity and overweight among children and adolescents in China. World J Pediatr 19, 1115–1126 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-023-00709-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-023-00709-7