Abstract

A 53-year-old man who had a history of ulcerative colitis (UC) for 2 years underwent colonoscopy as regular follow-up. The results showed an elevated lesion in the descending colon, which was diagnosed as plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) based on pathological findings. In situ hybridization for the Epstein–Barr virus-encoded RNA probe was positive. Fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed rearrangement of the MYC gene. He had been taking prednisolone, 5-aminosalicylic acid, azathiopurine, and ustekinumab at the diagnosis of PBL and had multiple prior therapies for UC including infliximab, tacrolimus, and tofacitinib due to steroid dependence. PBL is a rare aggressive B cell lymphoma initially described in the oral cavity of human immunodeficiency virus positive patients and it is suspected to have an association with immunocompromised status of patients. The number of cases of PBL in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients is extremely rare. All these patients were administered immunosuppressive therapy including thiopurines or biologics. IBD patients with immunosuppressive therapy have a higher potential for developing lymphoproliferative disorders. Clinicians should be aware of the risk of lymphoma, including PBL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a rare subtype of diffuse large B cell lymphoma initially described in the oral cavity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients [1]. Since its first report in HIV patients in 1997 [2], many studies have reported PBL in non-HIV patients, such as immunosuppressed patients, and PBL is also found in lesions other than those in the oral cavity, such as those in the gastrointestinal tract [3, 4]. PBL is very aggressive and has a poor prognosis, with a median overall survival of 6–19 months [5].

Patients with PBL and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), mainly Crohn’s disease, have been reported [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. All patients received immunosuppressive therapy, and most received treatment with thiopurines or biologics.

Good control of intestinal inflammation has the potential to reduce the occurrence of inflammation-related cancers [16]. In contrast, immunosuppressive drugs may promote malignancy. Among patients with IBD, a number of studies reported an association between thiopurine therapy with lymphoma [17, 18]; one study reported the association between the use of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) antagonists and lymphoma [19].

Herein, we present a rare lymphoproliferative disorder, PBL, occurring in a patient of ulcerative colitis (UC) during immunosuppressive therapy, which included thiopurine therapy, TNF-α antagonist, interleukin (IL)-12/23 antagonist, and Janus kinase inhibitor, despite the short time since the onset of UC.

Case report

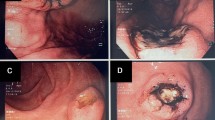

A 53-year-old Japanese man developed UC in November 2018, with diarrhea and bloody stools. The patient had no history of any autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or sarcoidosis. The UC lesion extended from the rectum to the left transverse colon. Following UC diagnosis, 5-aminosalicylic acid and prednisolone were administered and diarrhea and bloody stools were improved. However, this symptom relapsed in March 2019. Colonoscopy revealed widespread of ulcer from the rectum to the left transverse colon (Mayo endoscopic subscore of 3) (Fig. 1a and b). Blood test revealed increase in C-reactive protein levels to a maximum of 39.0 mg/dL and decrease in albumin and hemoglobin levels to a minimum of 1.4 and 6.7 g/dL, respectively. Mayo score was 12 and the condition of UC was considered severe and 80 mg/day of prednisolone was initiated. The response to prednisolone was insufficient and 5 mg/kg of infliximab (IFX) was initiated. However, there was no improvement and we considered that the patient showed primary non-response to TNF-α antagonist. We initiated tacrolimus and azathiopurine for the patient’s refractory severe UC and symptom improvement was observed. However, colonoscopy revealed that the ulcer did not resolve completely (Mayo endoscopic subscore of 3). Therefore, we changed tacrolimus to tofacitinib in November 2019. Tofacitinib was initially effective; however, there was relapse of bloody stool and we considered that the patient showed secondary non-response to tofacitinib. Therefore, we switched tofacitinib to ustekinumab in November 2020. However, clinical remission was not completely achieved. The patient underwent colonoscopy as a regular follow-up in June 2021.

a and b Colonoscopy reveals wide ulcer spread from the rectum to the left transverse colon (transverse colon (a) and splenic flexure(b)). c and d Colonoscopy reveals an elevated lesion in the descending colon near the splenic flexure, and this lesion has a whitish lesion in the center. A granular lesion with erosion spread is present around this lesion

Colonoscopy revealed an elevated lesion in the descending colon near the splenic flexure; this lesion had a whitish lesion in the center (Fig. 1c and d). A granular lesion with erosion spread was present around this lesion. These findings have never been observed in previous colonoscopies. Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (M-NBI) of the whitish lesion showed that the surface pattern was completely unclear and that the avascular area spread and microvessels were scattered (Fig. 2a and b). M-NBI of the elevated lesion showed an irregular surface pattern along with microvessels with caliber, meandering, and proliferation changes (Fig. 2a and c). One erosion was found in the transverse colon, and other areas where the mucosa had previous inflammation revealed mucosal scarring with pseudopolyposis. The Mayo endoscopic subscore, which has been 3 for a long period from the time of diagnosis of UC, was 2, and UC activity on colonoscopy was slightly recovered but still active in this area. The Mayo Clinic score was 4.

a and b Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (M-NBI) of the whitish lesion shows that the surface pattern is completely unclear and that the avascular area spread and microvessels are scattered. a and c M-NBI of the elevated lesion shows an irregular surface pattern along with microvessels with caliber, meandering, and proliferation changes

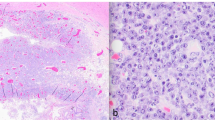

Histological examination revealed proliferation of immunoblast-like or plasmablast-like large atypical cells with basophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 3a and b). This was only found in the elevated lesion and erosive lesion around this elevated lesion in the descending colon. Biopsies from other parts of the colon did not show these findings. These cells were immunohistochemically positive for CD45, CD79a, CD38, CD138, CD56, MUM1, c-MYC, and p53 (Fig. 3d and e). However, they were negative for CD3, CD20, bcl-2, Cyclin D1, TdT, EMA, and CK AE1/AE3 (Fig. 3c). The Ki-67 proliferation index was high (> 90%) (Fig. 3f). In situ hybridization (ISH) for the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-encoded RNA probe was positive (Fig. 4a). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) revealed rearrangement of the MYC gene (Fig. 4b). EBV-DNA in serum by polymerase chain reaction was 3.64 log IU/ml at the diagnosis of PBL. Computed tomography (CT) revealed wall thickening in the descending colon near the splenic flexure (Fig. 5a). 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) showed uptake in the same lesion, which was observed on CT (Fig. 5b). Bone marrow aspirate and cerebrospinal fluid showed no abnormal findings. HIV antigen/antibody test results were negative. We finally made a diagnosis of stage I PBL. The international prognostic index (IPI) was low at 0. Weight loss, fever, and night sweats (B symptoms) were not observed.

a and b Hematoxylin–eosin staining of the colon biopsy. Proliferation of immunoblast-like or plasmablast-like large atypical cells with basophilic cytoplasm. c Immunohistochemical staining for CD20 is negative. Immunohistochemical staining for d CD138 and e c-MYC is positive. f Ki-67 proliferation index is high (> 90%)

Both ustekinumab and azathiopurine therapies were discontinued after the diagnosis of PBL. Prednisolone was used to control UC. The symptom and endoscopic finding of UC were not worsened under chemotherapy. The patient received chemotherapy with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and prednisone) for two cycles and dose-adjusted EPOCH (etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone) for three cycles. After chemotherapy, colonoscopy revealed that the elevated PBL lesion had flattened with erosion on the surface, and histological examination of the biopsy showed no tumor cells. FDG-PET/CT showed decreased uptake in the lesion. We believe that this case had a partial response to chemotherapy in a comprehensive manner.

Discussion

IBD primarily includes UC and Crohn’s disease, which cause gastrointestinal inflammation. Inflammation is frequently difficult to control, and IBD often relapses after treatment. Therefore, several drugs have been developed for their management. There are different drug types, including immunomodulators (thiopurines), TNF-α antagonists, interleukin (IL)-12/23 antagonist (ustekinumab), Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib), and anti-integrin agent (vedolizumab). Several guidelines [20, 21] recommend these drugs for the induction of remission or long-term maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe IBD. In our case, it was hard to control the colonic inflammation and we had to use several immunosuppressive drugs.

Colorectal cancer is a well-known complication in IBD patients [16, 22]. Colonic inflammation has a significant impact on the risk of development of colorectal tumors [23]. Some reports revealed that chronic inflammation also increased the risk of development of lymphoma [24]. Additionally, an increased risk of lymphoma is reported in patients with IBD who receive immunosuppressive therapies. In particular, several reports have demonstrated that thiopurine therapy for IBD is associated with an increased risk of lymphoma [17, 18]. Only one report revealed that anti-TNF monotherapy increased the risk of lymphoma in patients with IBD, and this risk was further increased by combination therapy with anti-TNF antagonists and thiopurines [19]. The relationship between anti-TNF therapy and lymphoma among IBD patients remains uncertain [25, 26]. It is unknown whether other biological therapies, such as ustekinumab and vedolizumab, increase the risk of lymphoma [18]. In our case, we needed to use anti-TNF therapy and other biological therapies in addition to thiopurine therapy because of the difficulty in controlling colonic inflammation. Despite these therapies, we could not achieve remission of UC and endoscopy showed sustained colonic inflammation over a long time. We speculated that the short duration of lymphoma occurrence from the onset of UC was due to immunosuppressive therapy and sustained colonic inflammation. Judging from previous evidence and the duration of drugs, thiopurine which was used over 1 year is mostly suspected to have an association with the occurrence of PBL as the causative drug. However, it cannot be denied that other drugs had no relationship with the occurrence.

PBL is defined by the World Health Organization as a very aggressive form of lymphoma with diffuse proliferation of large neoplastic cells, most of which show an immunoblast-like or plasmablast-like appearance [1]. Histologically, the neoplastic cells in PBL express a plasma cell phenotype with CD138 and MUM1 expression and are negative or weakly positive for B cell markers [1].

PBL has been reported in immunocompromised patients, such as HIV and post-transplant patients [10, 27]; therefore, immunosuppression is thought to play an important role in the development of PBL. It is not clear whether PBL is associated with IBD, especially immunosuppressive therapy. However, all PBL patients with IBD underwent immunosuppressive therapy before developing PBL, and most of them had undergone biologic or immunomodulator therapy alone or combination therapy, and an association was suspected. This is the first report to confirm the presence of EBV and MYC rearrangement in PBL patients with IBD, which may have an important role in the development of PBL.

To the best of our knowledge, among IBD patients, 11 patients reportedly developed PBL (Table 1) and among them only two patients had UC. Most studies have revealed that approximately 60% of PBL patients were in advanced clinical stages [3]. Of the 11 cases, only one patient was diagnosed using colonoscopy performed as a regular follow-up, similar to our case [9].

EBV is implicated in the development of several lymphoproliferative disorders, such as Burkitt’s lymphoma and Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Moreover, EBV is associated with the development of lymphoma in patients with IBD treated with thiopurines [28]. In PBL, a relationship with EBV has been suggested. A previous report revealed that the majority of HIV-positive cases and half of HIV-negative cases showed expression of EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) in ISH [29]. Of the 10 cases that were tested for the presence of EBV in PBL patients with IBD, nine cases were EBV-positive. All patients were treated with thiopurines or biologics, alone or in combination. In the present case, EBV infection was detected in the lesion. Based on these previous reports and our case, it is suggested that the use of immunosuppressants, such as thiopurines and/or biologics, may have led to increased susceptibility to infection or reactivation of EBV, which is believed to be related to the development of PBL.

Previous reports revealed that, most PBL cases with IBD showed the duration of IBD over 10 years. However, the duration of the case Zanelli reported was only 7 months. The drug duration of this patient was one week of azathiopurine and 2 months of IFX. This case and our case have a short duration of IBD. This short duration may be influenced by the direct effect of immunosuppressive therapy which may have an influence on EBV, in addition to the sustained colonic inflammation as described above. A previous report reported that the risk of lymphoma is elevated by the duration of exposure to thiopurines [17]. The relationship between the development of PBL and the duration of immunosuppressive therapy is still unclear and this needs to be clarified in future.

About half of the PBL cases showed MYC overexpression, as detected in immunohistochemistry [4, 27]. The rearrangement of MYC has been suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of PBL [30, 31]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of MYC rearrangement in patients with PBL and IBD. In two studies, prognosis reports state that MYC rearrangement is associated with a worse outcome [4, 32].

Owing to its rarity, there is no standard strategy for the treatment of PBL. Additionally, no standard chemotherapy regimen has been established yet. Recently, several studies reported that bortezomib in combination with conventional chemotherapy showed a high response [33, 34]. There are reports showing that hematopoietic cell transplantation is effective, but the number of reported patients is small [35]. Good prognosis is reported to be positively associated with low IPI scores and achievement of complete response [27].

In IBD patients with cancer, the management of IBD therapy is not clear. In general, it is suggested that thiopurines and anti-TNF antagonists should be stopped until cancer therapy is completed [36]. It is also suggested that among patients with a history of malignancy that do not respond to 5-aminosalicylic acid and local corticosteroids, the use of anti-TNF antagonists and systemic corticosteroids should be considered [36]. There are no reports showing that ustekinumab increased the risk of malignancy in IBD [37]. We considered that biologics may have an influence on the progression of lymphoma and cessation of azathiopurine and ustekinumab administration along with continued prednisolone administration can control UC.

In conclusion, IBD patients with immunosuppressive therapy, especially thiopurines, have a higher potential for developing lymphoproliferative disorders than those without the therapy.

Clinicians should be aware of the risk of lymphoma, including PBL, which shows an aggressive course in IBD patients with immunosuppressive therapy, and they should regularly check for its onset.

References

Campo E, Stein H, Harris NL. Plasmablastic lymphoma. In: Lyon F, editor. IARC Press. Campo E, Harris NL: WHO classification of Tumors of hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Serdlow SH; 2017. p. 321–2.

Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413–20.

Castillo JJ, Reagan JL. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a systematic review. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:687–96.

Morscio J, Dierickx D, Nijs J, et al. Clinicopathologic comparison of plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV-positive, immunocompetent, and posttransplant patients: single-center series of 25 cases and meta-analysis of 277 reported cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:875–86.

Lopez A, Abrisqueta P. Plasmablastic lymphoma: current perspectives. Blood Lymphat Cancer. 2018;8:63–70.

Teruya-Feldstein J, Chiao E, Filippa DA, et al. CD20-negative large-cell lymphoma with plasmablastic features: a clinically heterogenous spectrum in both HIV-positive and -negative patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1673–9.

Redmond M, Quinn J, Murphy P, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma presenting as a paravertebral mass in a patient with Crohn’s disease after immunosuppressive therapy. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:80–1.

Plaza R, Ponferrada A, Benito DM, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma associated to Crohn’s disease and hepatitis C virus chronic infection. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:628–32.

Liu L, Charabaty A, Ozdemirli M. EBV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma in a patient with Crohn’s disease after adalimumab treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e118–9.

Luria L, Nguyen J, Zhou J, et al. Manifestations of gastrointestinal plasmablastic lymphoma: a case series with literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11894–903.

Liu C, Varikatt W, P’ng CH. Plasmablastic lymphoma presenting as a colonic stricture in Crohn’s disease. Pathology. 2014;46:77–9.

Zanelli M, Ragazzi M, Valli R, et al. Unique presentation of a plasmablastic lymphoma superficially involving the entire large bowel. Pathol Res Pract. 2015;211:1030–3.

Maung SW, Desmond R, McHugh J, et al. A coincidence or a rare occurrence? A case of plasmablastic lymphoma of the small intestines following infliximab treatment for Crohn’s disease. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:149–50.

Ghosh G, Jacob V, Wan D. Plasmablastic lymphoma in a patient With Crohn’s disease After extensive immunosuppressive therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:e41–2.

Sato S, Nakahara M, Kato K, et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma occurring in the vicinity of enterocutaneous fistula in Crohn’s disease. J Dermatol. 2020;47:e442–3.

Beaugerie L, Kirchgesner J. Balancing benefit vs risk of immunosuppressive therapy for individual patients With inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:370–9.

Kotlyar DS, Lewis JD, Beaugerie L, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:e844.

Beaugerie L, Rahier JF, Kirchgesner J. Predicting, preventing, and managing treatment-related complications in patients With inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:1324-1335.e2.

Lemaitre M, Kirchgesner J, Rudnichi A, et al. Association between use of thiopurines or tumor necrosis factor antagonists alone or in combination and risk of lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA. 2017;318:1679–86.

Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, et al. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1450–61.

Nakase H, Uchino M, Shinzaki S, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease 2020. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:489–526.

Jess T, Rungoe C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:639–45.

Rutter M, Saunders B, Wilkinson K, et al. Severity of inflammation is a risk factor for colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:451–9.

Ekström Smedby K, Vajdic CM, Falster M, et al. Autoimmune disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: a pooled analysis within the InterLymph Consortium. Blood. 2008;111:4029–38.

Muller M, D’Amico F, Bonovas S, et al. TNF inhibitors and risk of malignancy in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:840–59.

Dahmus J, Rosario M, Clarke K. Risk of lymphoma associated with anti-TNF therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: implications for therapy. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020;13:339–50.

Tchernonog E, Faurie P, Coppo P, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of plasmablastic lymphoma patients: analysis of 135 patients from the LYSA group. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:843–8.

Dayharsh GA, Loftus EV Jr, Sandborn WJ, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-positive lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:72–7.

Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Stachurski D, et al. Clinical and pathological differences between human immunodeficiency virus-positive and human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients with plasmablastic lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:2047–53.

Valera A, Colomo L, Martínez A, et al. ALK-positive large B-cell lymphomas express a terminal B-cell differentiation program and activated STAT3 but lack MYC rearrangements. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:1329–37.

Loghavi S, Alayed K, Aladily TN, et al. Stage, age, and EBV status impact outcomes of plasmablastic lymphoma patients: a clinicopathologic analysis of 61 patients. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:65.

Castillo JJ, Furman M, Beltrán BE, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: poor prognosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Cancer. 2012;118:5270–7.

Dittus C, Grover N, Ellsworth S, et al. Bortezomib in combination with dose-adjusted EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin) induces long-term survival in patients with plasmablastic lymphoma: a retrospective analysis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:2121–7.

Castillo JJ, Guerrero-Garcia T, Baldini F, et al. Bortezomib plus EPOCH is effective as frontline treatment in patients with plasmablastic lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2019;184:679–82.

Al-Malki MM, Castillo JJ, Sloan JM, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation for plasmablastic lymphoma: a review. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:1877–84.

Annese V, Beaugerie L, Egan L, et al. European evidence-based consensus: inflammatory bowel disease and malignancies. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:945–65.

Sattler L, Hanauer SB, Malter L. Immunomodulatory agents for treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (review safety of anti-TNF, anti-integrin, anti IL-12/23, JAK inhibition, sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator, azathioprine/6-MP and methotrexate). Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2021;23:30.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: HO and YM. Acquisition of data: HO, YM, ST, TI, DK, MH, KI, HK, MI, and HI. Data analysis and interpretation: HO, YM, HK, and MI. Drafting of the article: HO. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: HO and YM. Final approval of the article: HO.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human rights

All procedures followed have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for inclusion in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ogiyama, H., Murayama, Y., Tsutsui, S. et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma occurring in ulcerative colitis during treatment with immunosuppressive therapy. Clin J Gastroenterol 16, 198–205 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-023-01754-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-023-01754-5