Abstract

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is associated with lower survival and greater unmet need compared with some other hematologic malignancies (HMs). Despite differences in acuteness between AML and other HMs, the burden of family caregivers (FCs) of patients with these malignancies offer similar patient experiences. A targeted literature review was conducted to explore FC burden of patients with AML and HM with and without hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). Instruments to measure and interventions to address FC burden were identified.

Methods

Studies on economic burden and compromised health-related quality of life (HRQoL) associated with FC burden, family affairs, and childcare from 1 January 2010 to 30 June 2019 were identified through database and hand searches. Published English articles on randomized controlled trials or standardized qualitative or quantitative observational studies were included. FCs were those in close familial proximity to the patient (i.e., spouse, parents, children, relatives, other family members, significant others).

Results

Seventy-one publications were identified (AML, n = 3; HM, n = 29; HSCT, n = 39). Predominant burden categories included humanistic (n = 33), economic (n = 17), and interventions (n = 22); one study was classified as humanistic and economic. FCs lack sufficient resources to manage stressors and experience negative psychological, behavioral, and physiological effects. FCs of patients with HMs reported post-traumatic stress disorder, significant sleep problems, moderate-to-poor HRQoL, and negative impacts on family relationships. Instruments designed to measure caregiver burden were generic and symptom-specific. Educational, expressional, and self-adjustment interventions were used to improve FC burden.

Conclusion

Findings indicate a need for additional research, public health approaches to support FCs, and effective interventions to address FC burden. Minimizing FC burden and improving quality of life may reduce the overall healthcare service use and allow FCs to more effectively fulfill caregiver tasks. Support systems to alleviate caregiver burden may create reinforced integrators, thus positively affecting quality of life and possibly the outcomes of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Acuteness between acute myeloid leukemia and other hematologic malignancies differ, yet the burden on family caregivers of patients with these malignancies offer similar patient experiences. |

Studies in acute myeloid leukemia focused on caregivers are sparse despite the low survival rate associated with this disease, and prospective studies in adults and pediatric patients are needed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the burden on caregivers. |

Systematic interventions are needed to support family caregivers of patients with acute myeloid leukemia, hematologic malignancies, and other hematologic malignancies due to hematopoietic stem cell transplant. |

Minimizing family caregiver burden and improving caregiver quality of life may reduce the use of overall healthcare services and allow caregivers to more effectively fulfill their roles. |

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a common form of acute leukemia in the USA [1]. In 2019, there were an estimated 21,450 new cases of acute AML in the USA and 10,920 estimated deaths [2]. The incidence of AML increases with age and patients over 65 years old are diagnosed with AML more frequently than younger patients. The median age at diagnosis is 68 years in the USA [1]. Complete remission of AML is achieved with intensive therapy in 60–80% of younger patients and in 40–60% of patients aged 60 years or older. Only 20–30% of patients can achieve durable remissions after reinduction in the relapsed/refractory setting, and the rate of survival after relapse is poor [3]. In addition to poor outcomes that create an unmet need in patients with AML, patients with AML report poor health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and psychological distress [4,5,6].

Compared to other forms of leukemia, AML is associated with lower 5-year survival and significant unmet need related to treatments and patient quality of life [7, 8]. AML shares similarities with other hematologic malignancies (HMs) in terms of adverse patient outcomes such as economic and humanistic detriments, some of which are shared across both AML and other HMs due to hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). As such, family caregivers (FCs) such as significant others, caregivers, and family members experience distress when caring for these patients [9, 10]. FCs find themselves under excess levels of stress [11, 12] and may experience burden associated with the shift in responsibility during transition from inpatient to outpatient care [13]. Therefore, FCs may benefit from specifically structured and systematic interventions [14] and appropriate “fit-for-purpose” instruments to assess FC burden. Despite differences in acuteness between AML and other HMs, the literature on FC burden of patients with them offer similar patient experiences. Therefore, we conducted a targeted literature review (TLR) to explore the FC burden of patients with AML and HMs, including any form of leukemia.

Methods

The primary objectives of this TLR were to explore FC burden of patients with AML, patients with HM (including any form of leukemia) who did not receive HSCT (referred to as HM below), and patients with HM receiving HSCT (referred to as HSCT below). The exploratory objectives were to identify instruments used to measure FC burden and interventions used to address FC burden.

Literature Search Strategy

The data sources used to identify the relevant studies were published in Pubmed, Embase, MEDLINE® (via Ovid), and Ovid. The database search strings identified all relevant studies (full papers or abstracts from any conferences) indexed in Embase and were modified for MEDLINE and the Cochrane Library, to account for differences in syntax and thesaurus headings. Searches included terms for free text and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms. Search terms included the following: acute myeloid leukemia with multiple spelling variations; hemopoietic stem cell transplantation, stem cell transplantation, or HSCT; caregiver burden, caregiver support, caregiver stress, caregiver strain, family burden, or titles of multiple caregiver indexes and inventories; financial problem, financial toxicity, productivity loss, absenteeism, presenteeism, wage loss, low or low income (Supplementary Table S1).

Eligibility Screening

FC was defined as those in close familial proximity to the patient by family ties, such as spouse, parents, children, relatives, other family members, or significant others. This TLR did not include the burden experienced by healthcare professionals or providers (e.g., nurse practitioners, physicians). The title and abstract of citations identified in the electronic database searches were screened to assess eligibility based on the eligibility criteria. Full publications of studies deemed to be potentially relevant were then obtained and studies assessed on the basis of the full texts. The reasons for exclusion of non-relevant citations were documented descriptively and using a prospectively designed code system. English articles on randomized controlled trials or qualitative or quantitative observational studies published from 2010 to 2019 that fit the following PICOS (P: population, I: intervention, C: comparator, O: outcomes, and S: study design) criteria were included. The study population included FCs (including spouses, parents, children, relatives, other family members, or significant others) of patients with AML, HM and oncologic diseases who also received HSCT, and patients with HMs including “leukemia” in general. Patients receiving HSCT for reasons other than HM or AML were excluded, as were all other populations that did not meet the eligibility criteria. Papers were not restricted on the basis of intervention or comparisons. Interventions for FC burden management and instruments for FC burden measurement are separately reported.

Studies were included if they reported the following key study outcomes: humanistic burden (i.e., HRQoL, such as distress, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, physical function, social function, role function, emotional function, cognitive function, and mental/psychological burden), economic burden (i.e., productivity challenges, loss of employment, financial burden), or instruments to measure caregiver burden.

Study Selection

Any study was included that reported on economic burden, including studies with indirect costs, and compromised quality of life associated with FC burden while trying to keep work and life balance faced with work, family affairs, childcare (for adults, at least one of whom diagnosed with AML and with children that need care), including HRQoL. Additionally, hand searches were performed on references from select seminal articles and checked for duplication.

Two reviewers independently selected studies for inclusion using pre-specified PICOS eligibility criteria in two phases: (1) title/abstract screening, (2) full-text screening. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were settled by a third reviewer.

Data Extraction

Relevant data from included studies were extracted into a data extraction table in Microsoft® Excel, which collected data on general information (i.e., title, type of publication, year, authors, country), study characteristics (i.e., study objective, study design, study period, follow-up period, details of interventions/comparators, data analysis methods), participant demographics (i.e., patient and target population characteristics; inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, number of target population, age, gender, marital status, education level, income level, relationship with patients, if they have children or not), instrument used to measure caregiver burden or quality of life, reported outcomes, author conclusions, and limitations. Data extraction was conducted by a single analyst, and randomly selected 20% of included studies were quality checked by another analyst. Quality assessments were performed of the final articles included in the TLR.

Ethics Compliance

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals by any of the authors.

Results

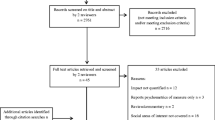

The electronic database search identified 670 citations, of which 147 were identified as duplicates and excluded. The remaining 523 citations were screened on the basis of title and abstract, and 350 were then excluded, leaving 173 citations to be screened on the basis of the full publications. During full-text screening, 127 publications were subsequently excluded, resulting in 44 publications from the electronic database searches to be included in the TLR. Also, 27 additional full-text articles were identified by hand through reference search, resulting in 71 full-text publications included in the TLR (Fig. 1).

The publications were categorized according to the target population of the study: AML (n = 3), HM (n = 29), and HSCT (n = 39). The AML category included papers on AML only. For the HM and HSCT categories, AML may have been included as a HM if other leukemias were also reported. The HM category included papers that reported FC burden with patients with HM including “leukemia” in general. These studies may have included multiple cancer types as long as they also included “leukemia”, “acute leukemia”, “hematologic cancer”, “hematologic oncologic disease”, or “blood cancer” among the reported cancer types. The HSCT category included publications that reported FC burden of patients with HM receiving HSCT; studies were excluded if patients were receiving HSCT for diseases other than HM (e.g., sickle cell disease, severe infections). The papers were then further categorized into burden categories based on predominant burden described: humanistic (n = 33), economic (n = 17), and interventions (n = 22) (Fig. 2); one study [15] was included in both humanistic and economic categories.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients and FCs

Overall, 65 articles reported demographics characteristics of patients and/or FCs. The most frequently reported demographic characteristics of caregivers included age, gender, marital status, relationship between caregivers and patients, employment status, and income level. With respect to age of patients and caregivers, the mean age of sample adult patients ranged from 40.7 to 64.7 years, and the mean age of sample pediatric patients ranged between 5.6 and 13.4 years. As for the age of caregivers, the mean age of the sample caregivers of adult patients was between 33.1 and 61.6 years, while the mean age of caregivers of pediatric patients ranged from 34.6 to 44.7 years. Among 54 articles that included FC gender, 40 articles reported that at least 60% were female. Among the 46 articles that included marital status, 37 reported that at least 60% of FCs were married. Among papers that reported the relationship between the patient and FC, many (41.7–100%) FCs were spouses of adult patients. Additionally, almost 100% of FCs of pediatric patients were their parents and 48–100% were mothers. Among the 28 papers that reported work status, caregivers were either employed (i.e., active, full-time, part-time, independent worker, other) or not employed (i.e., retired, on leave, homemaker, or nonactive). For adult and pediatric patients, 15.4–93.8% and 35.3–60.0% of FCs, respectively, were employed full-time.

Humanistic FC Burden

A total of 33 studies examined FC humanistic burden (Table 1). The most common types of psychosocial burden were anxiety, depression, and distress.

Caregivers of Patients with AML

Two articles were identified that reported humanistic FC burden of patients with AML [16, 17]. It was found that negative psychological, behavioral, and physiological impact of FC burden could drive extreme notions [16] in caregivers of patients with AML. As the intensity of FC burden of patients with AML increased, positive caregiving experience was significantly diminished [17]. Furthermore, positive aspects of caregiving were negatively associated with high levels of burden, with FCs of patients with AML reporting high levels of inconvenience and low levels of care satisfaction [17].

Caregivers of Patients with HM Undergoing HSCT

Twenty-one studies reported humanistic FC burden in patients with HM undergoing HSCT. Sleep and psychosocial burden are often-reported FC burdens associated with HSCT [36, 37]. FCs have significant sleep problems, including sleep disturbance, wake after sleep onset, and insomnia [30, 36, 37]. FCs without proper psychosocial support suffered from significant role strain. Quality of life was moderate to poor for caregivers. The more prepared that caregivers felt in their role, the better they felt about the care they were providing [21]. In terms of psychosocial burden, anxiety, depression, stress, and distress were among often-reported psychological burdens experienced by FCs [26, 31]. One study of patients scheduled to undergo HSCT revealed that their caregivers reported higher levels of anxiety and depression than the patients (P < 0.01); additionally, 30% of caregivers versus 17% of patients were clinically anxious [31]. More seriously, high levels of anxiety and distress were shown to lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and adverse outcomes for both the patient undergoing allogeneic HSCT and the FC. A study assessing the rates and risk factors for PTSD among patients undergoing HSCT and their FCs revealed that rates of PTSD were significantly higher among FC than patients (6.6% vs 3.3%; P = 0.02) [26]. Moreover, FCs also reported fatigue, and negative experience in sexual and family relationships [30].

Caregivers of Patients with HMs Including Leukemia

Ten studies reporting humanistic caregiver burden of adult and pediatric patients with one of multiple forms of cancer that included HM/leukemia were also identified. Over 75% of adult patients with HMs received informal care. Being male (OR = 0.26), having a partner (OR = 0.14), and being employed (OR = 0.11) were associated with lower likelihood of receiving informal care (95% CI not reported; significance level ≤ 0.10) [45]. Patients diagnosed with acute leukemia were 6.4 times (95% CI not reported; significance level ≤ 0.05) more likely to receive family care (informal care) during the pre-transplant period relative to patients with lymphoma, and 42.2 times (95% CI not reported; significance level ≤ 0.01) more likely to receive it during the second and third year of post-transplantation [45].

The burden experienced by children who were caregivers of their parents differs from that of parent caregivers. Adult children-caregivers of their ill parents with high parent-patient dependency (vs lower dependency) reported higher PTSD, higher caregiver burden, and higher dissatisfaction with social support, which played a significant mediator role between psychological morbidity and caregiver burden [48]. Parent caregivers of children with other cancers including leukemia experience depression, anxiety, and stress due to their child’s symptom burden, and also uncertainty during survivorship. In a study of parent caregivers and their children with cancer, more than two thirds of caregivers screened positive for depression and a positive correlation was noted between the child’s symptom burden and depressive symptoms among caregivers [44].

Child cancer survivors and their family members continue to live in fear even after treatment has concluded. One study reported that child cancer survivors indicated that both parents and children generally had similar levels of anxiety and stress during survivorship, and that survivors had significantly less knowledge of latent effects of cancer treatment in advance of receiving treatment than their parents [42]. The stress of a child with cancer affects sibling relationships as well. In a study of families with an adult parent caregiver, a child with cancer, and another child at least 5 years younger than the child with cancer, higher average levels of general life stressors, cancer-related stressors, and economic stress were more strongly associated with higher sibling conflict at the end of the first year of treatment [40]. Furthermore, although caregiver stress was found to decrease over time, it could be negatively impacted by being a single parent and by the pediatric patient being the only child [47]. In a study of children who survived cancer involving central nervous system-directed treatments, parents of survivors with neurocognitive late effects, particularly executive functioning difficulties, experience high caregiver stress [46].

Caregivers of younger patients with a diagnosis of AML had higher intrusion scores (caregiver cancer-specific distress as measured on the Impact of Event Scale questionnaire) than caregivers of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, solid tumors, or brain tumors. Additionally, caregivers had higher Impact of Event Scale scores and intrusion scores if their child was still under treatment, compared to those off-therapy. Additionally, income status affected the FCs psychological burden. Caregivers with household incomes below US $40,000 reporter higher distress scores than those with incomes of at least US $40,000 [43].

Economic FC Burden

A total of 17 studies examined FC economic burden (Table 1). Few reports on the economic FC burden of patients with AML have been published. The only AML economic burden study reported that in China, 55.7% of FCs abandoned a child with AML because of loss of hope for a cure, extreme financial hardship due to no healthcare coverage, and inability to pay for treatment [49]. However, policies may have improved since the report was published as data was collected from 2002 to 2012.

Both short-term and long-term financial burden experienced by caregivers were studied. Financial burden prior to HSCT and up to 2 years after HSCT was reported in reports of these studies. A case report estimated that the annual pharmaceutical out-of-pocket costs of two patients receiving HSCT were US $12,400 and US $16,000 in 2017, respectively [51]. In another study, on the basis of survey data results from 25 patients/caregivers from 2009 to 2010, the median (range) reduction in household income from diagnosis to HSCT was US $15,690 (US $3500–70,000). In the first 3 months after HSCT, the median (range) out-of-pocket patient cost was US $2440 (US $199–13,769), and patients and caregivers who had to travel had higher total median expenses (US $5247) compared to those who did not (US $716) [52]. FCs of patients undergoing HSCT also led to substantial work loss. Two years after HSCT, 54% of patients had not returned to work, with 80% of patient-caregiver dyads reporting a significant detrimental effect on household income [50].

Parent FCs of children with HM/leukemia face significantly heavier economic burden 1–5 years from diagnosis than parents with healthy children as a result of unexpected hospitalizations (approximately 20% of families reported at least five hospitalizations) and work disruption [64]. In another report, 94% of FCs of pediatric patients reported some sort of work disruption and 50% of the poorest families reported losing more than 40% of their annual household income [53]. A study of patients with HMs reported that in 85.4%, 80.5%, and 33.3% of households, more than 40% of monthly income would have to be devoted to formal care in the short, medium, and long term, respectively, because of inability to find sustainable informal care [59]. One study found that wives of patients with cancer were less likely to be employed 2–6 years after diagnosis; however, wives or husbands of survivors that were working at follow-up were more than twice as likely to be working full-time and worked more hours per week than other working spouses [57].

Interventions and Instruments to Measure Burden

In the TLR, 22 studies investigated different approaches to help relieve or cope with caregiver burden (Table 1). Of them, four articles targeted caregivers of pediatric patients only and five included both adult and pediatric patients.

The interventions were classified into four primary types. Interventions that used education informed caregivers about how to solve the problems they are facing. Some interventions stressed the importance of expression and communication. Others focused on self-adjustment, which included engaging in relaxation techniques. In recent years, studies focused on using digital/mobile health interventions to help FCs relieve burdens.

Educational intervention programs resulted in improvements in self-efficacy and distress, better health outcomes (e.g., fatigue) [67], reduced mental health service use [77], and lower levels of stress, depression, and anxiety [14, 77]. Expressional interventions were also shown to be effective in decreasing anxiety and depression [70]. Additionally, FCs and patients who participated in couples-based communication intervention reported feeling supported and closer to their partner [74]. FCs who participated in self-adjustment interventions, such as “caregiver’s week” and mindfulness-based stress management programs, reported positive feedback and thought the programs would be helpful [78]. A tablet-based health information technology application was shown to decrease depression, distress, fatigue, and anxiety for FCs of patients undergoing HSCT [69].

Among the included articles, instruments designed specifically to measure caregiver burden were captured and included those designed for parents of pediatric patients. In addition, both generic instruments and symptom-specific instruments were captured in the TLR (Table 1). The instruments/scales in the latter category were designed to assess specific diseases or symptoms (e.g., sleep, distress, mood, depression, anxiety, etc.). Of the instruments specifically designed for caregiver burden, the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) questionnaire and the Caregiver Quality of Life Index Cancer (CQOLC) scale [86] were used most frequently. The CRA questionnaire consists of five subscales (24 items), including disrupted schedule, financial problems, lack of family support, health problems, and self-esteem. It can be used for measuring both positive and negative caregiver reactions. The CRA has been proven to be a reliable and valid instrument for assessing burden of FCs of patients with cancer, with the standardized Cronbach’s alpha varying between 0.62 and 0.83. The CQOLC is a 35-item instrument that assesses quality of life for FCs of patients with cancer, including the physical, social, emotional, and financial aspects of well-being [87]. The reliability and validity of different language versions (i.e., English, Korean, Turkish, French, Chinese) have been demonstrated [87,88,89,90,91].

Discussion

The main purpose of this review was to explore the caregiver burden of patients with AML primarily; the review was expanded to include other HMs including “leukemia” because of lack of evidence on FC burden of patients with AML only. Most of the 71 articles included in the TLR emphasized patients undergoing HSCT. Only three studies focused specifically on the caregivers of patients with AML (i.e., patients with leukemia types other than AML were not included). This paucity of findings in the literature demonstrates a significant unmet need in determining caregiver burden of patients with AML and illustrates the need for a greater focus on this important aspect of AML management. Because the adverse patient outcomes associated with AML can have similar connotations to those observed with HM and HSCT, the scope of the TLR was expanded to explore the FC burdens of patients with AML, HM (including leukemias), and HSCT; however, the need for a greater understanding of caregiver burden of patients with AML should not be overlooked.

AML accounts for 1.1% of all cancers [92] and is more frequently seen in patients over 65 years of age [1]. By 2030, it is estimated that 73 million people in the USA will be at least 65 years of age [93], many of whom may require care. Therefore, the FC burden associated with AML, HMs, and HSCT will have important social, humanistic, and economic implications.

The FC burden may not be limited to or unique to patients with AML. Working FCs who have to provide consistent and demanding care may face significant impediments due to economic burden and compromised quality of life [21, 51, 59]. Common FC burden experiences reported among HMs were economic burden such as work disruptions and high out-of-pocket costs [59].

Many FCs currently do not have access to sufficient resources to be able to manage and control their stressors and, therefore, experience negative psychological, behavioral, and physiological effects [26, 31]. Overall, studies evaluating FC burden in pediatric caregivers focused on psychological burden, rather than physical or financial burden. This may, in part, be due to the likelihood that pediatric caregivers are parents of the patients, most of whom are employed middle-aged adults, and, therefore, financial implications and their own healthcare issues are less important to them than the psychological stresses they are facing. Caregivers of children undergoing HSCT are likely to have a higher employment rate and household income than those of caregivers of adult/elderly patients. Likewise, the reported mean age of FCs of pediatric patients was 35 to 45 years old. Therefore, they are less likely to suffer health problems. Thus, these factors may explain why relevant research for this group emphasized psychological burden.

Federal polices in the USA increasingly incentivize community-based as opposed to institutional care, presuming that family members or friends are available and able to provide these services, or to at least coordinate care services [94]. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has stated that caregiving and the resultant stress on caregivers is an important public health issue that affects the quality of life of millions of individuals [95]. The survey results in the CDC report indicated some major findings: (1) nearly one in four adults over the age of 45 years provided care or assistance to a family member or friend with a health problem or disability in the last 30 days; (2) almost one in three caregivers provided 20 or more hours per week of care; (3) over half had given care or assistance for 24 months or more; (4) the demands of caregiving are emotionally and physically challenging, with nearly one in seven caregivers reporting 14 or more mentally unhealthy days in the past month, and nearly one in six reported 14 or more physically unhealthy days in the past month; (5) four in ten caregivers reported having two or more chronic diseases, showing that caregivers may often neglect their own personal health needs.

FCs spend an estimated US $190 billion per year on their care recipients for out-of-pocket, care-related expenses [96]. In 2011–2012, informal caregiving in the USA was estimated to account for about 30 billion hours and a loss of approximately US $522 billion in forgone wages [97]. Therefore, the financial strain associated with the caregiving experience can be considerable; systemic buffers of stress, such as workplace or social policies, can help mitigate some of the effects from the financial aspects of caregiving [94].

A limitation of the included articles is the small sample size of each study, and thus the results and conclusions may not be generalizable to a broader population. We included studies from a number of countries; differences in underlying healthcare systems and in the social and economic systems of countries mean that the studies are not directly comparable and may further limit the generalizability of the observations. The studies also included a homogenous sample and were typically single-center studies, again limiting the generalizability of the observations. Most studies were not longitudinal, and the TLR included almost entirely observational studies, with very few randomized controlled trials reported, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions on the nature and degree of FC burden. Furthermore, selection and publication biases are potential limitations of this TLR, limiting the ability to establish causality. Some articles were included because the sample population of these studies included leukemia among other cancer diagnoses. A broad inclusion of patients with cancer may cause confounding results. For example, Teixeira and Pereira [48] conducted a study in which it was not possible to distinguish results of patients with AML, acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), and solid tumors. The AML/ALL patient population in this study accounted for less than 12% of the total population. Nevertheless, this study was included because the study population included patients with leukemia. Although grouping leukemic and non-leukemic FC burdens may create bias or confounding in results, excluding publications that included patients with leukemia could have resulted in missing relevant information. Papers that did not mention leukemia among the enrolled cancer populations were excluded, even where the population included patients who had received stem cell therapy [98]; this may have led to the exclusion of potentially insightful information. Finally, the TLR was conducted for papers published from 2010 onwards, thus omitting any earlier publications on FC burden.

This TLR demonstrated more studies are warranted that target FC burden of patients with AML because only three such studies were found. In particular, prospective studies assessing FC burden in pediatric and adult patients would be useful. Caregivers of patients with AML may experience severe consequences of burden from early in their caregiving role. Although there could be some similarities with FC burden of other patients with HM and patients receiving HSCT, more attention is needed to separate the FC burden of unique HM diseases for more effective intervention design because each case of leukemia has a unique trajectory of impact on FC burden. Similarly, it is likely that the FC burden for caregivers of pediatric patients differs from that facing caregivers of adult patients; in particular, FC burden for parents of pediatric patients may differ from FC burden for other family members. We suggest that prospective studies are undertaken to assess the HRQoL and humanistic burden and the economic burden for FCs of adult and pediatric patients with AML. To provide a more comprehensive understanding of the burden on FCs, we suggest a more granular approach would be to identify FC burden with patient–burden dyads, an approach which has the potential to highlight a pathway towards meaningful interventions that can be structured systematically to answer the needs of patients with AML and their FCs. Once humanistic and economic burdens have been more comprehensively identified and quantified, further study on the effect of systematic interventions to reduce FC burden should be undertaken.

Conclusion

A need exists for systematic interventions to support FCs of patients with AML, HM, and HSCT. Examples of effective interventions could include work support, locally available specialized health support, and financial support for caregivers of working age. Reducing FC burden and improving FC quality of life may reduce the use of overall healthcare resource utilization. Caregivers can thus become more effective in fulfilling their roles. Systematic support systems designed to alleviate or relieve caregiver burden may create reinforced integrators, thus having a positive and lasting effect on the quality of life and outcomes of patients with AML and other cancer types.

References

Shallis RM, Wang R, Davidoff A, Ma X, Zeidan AM. Epidemiology of acute myeloid leukemia: recent progress and enduring challenges. Blood Rev. 2019;36:70–87.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34.

Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129:424–47.

Boucher NA, Johnson KS, LeBlanc TW. Acute leukemia patients’ needs: qualitative findings and opportunities for early palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:433–9.

Buckley SA, Kirtane K, Walter RB, Lee SJ, Lyman GH. Patient-reported outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia: where are we now? Blood Rev. 2018;32:81–7.

Kayastha N, Wolf SP, Locke SC, Samsa GP, El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc TW. The impact of remission status on patients’ experiences with acute myeloid leukemia (AML): an exploratory analysis of longitudinal patient-reported outcomes data. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:1437–45.

Davis AS, Viera AJ, Mead MD. Leukemia: an overview for primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:731–8.

Wiese M, Daver N. Unmet clinical needs and economic burden of disease in the treatment landscape of acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24:S347–55.

Applebaum AJ, Bevans M, Son T, et al. A scoping review of caregiver burden during allogeneic HSCT: lessons learned and future directions. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:1416–22.

El-Jawahri AR, Traeger LN, Kuzmuk K, et al. Quality of life and mood of patients and family caregivers during hospitalization for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2015;121:951–9.

Harding R, Gao W, Jackson D, Pearson C, Murray J, Higginson IJ. Comparative analysis of informal caregiver burden in advanced cancer, dementia, and acquired brain injury. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:445–52.

Kim Y, Carver CS, Shaffer KM, Gansler T, Cannady RS. Cancer caregiving predicts physical impairments: roles of earlier caregiving stress and being a spousal caregiver. Cancer. 2015;121:302–10.

Vaughn JE, Buckley SA, Walter RB. Outpatient care of patients with acute myeloid leukemia: benefits, barriers, and future considerations. Leuk Res. 2016;45:53–8.

Laudenslager ML, Simoneau TL, Kilbourn K, et al. A randomized control trial of a psychosocial intervention for caregivers of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients: effects on distress. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50:1110–8.

Aung L, Saw SM, Chan MY, Khaing T, Quah TC, Verkooijen HM. The hidden impact of childhood cancer on the family: a multi-institutional study from Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2012;41:170–5.

Bevans MRNPL, Sternberg EMMD. Caregiving burden, stress, and health effects among family caregivers of adult cancer patients. JAMA. 2012;307:398–403.

Grover S, Rina K, Malhotra P, Khadwal A. Correlates of positive aspects of caregiving among family caregivers of patients with acute myeloblastic leukaemia. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2018;34:612–7.

Bergkvist K, Larsen J, Johansson UB, Mattsson J, Fossum B. Family members’ life situation and experiences of different caring organisations during allogeneic haematopoietic stem cells transplantation—a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27:1.

Bevans M, Wehrlen L, Prachenko O, Soeken K, Zabora J, Wallen GR. Distress screening in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSCT) caregivers and patients. Psychooncology. 2011;20:615–22.

Coleman K, Flesch L, Petiniot L, et al. Sleep disruption in caregivers of pediatric stem cell recipients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65: e26965.

Cooke L, Grant M, Eldredge DH, Maziarz RT, Nail LM. Informal caregiving in hematopoietic blood and marrow transplant patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:500–7.

Deniz H, Inci F. The burden of care and quality of life of caregivers of leukemia and lymphoma patients following peripheric stem cell transplantation. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2015;33:250–62.

Jim HS, Quinn GP, Barata A, et al. Caregivers’ quality of life after blood and marrow transplantation: a qualitative study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:1234–6.

Jim HS, Quinn GP, Gwede CK, et al. Patient education in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant: what patients wish they had known about quality of life. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:299–303.

Larsen HB, Heilmann C, Johansen C, Adamsen L. An analysis of parental roles during haematopoietic stem cell transplantation of their offspring: a qualitative and participant observational study. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:1458–67.

Liang J, Lee SJ, Storer BE, et al. Rates and risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology among adult hematopoietic cell transplant recipients and their informal caregivers. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:145–50.

Norberg AL, Forinder U. Different aspects of psychological ill health in a national sample of Swedish parents after successful paediatric stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:1065–9.

Norberg AL, Mellgren K, Winiarski J, Forinder U. Relationship between problems related to child late effects and parent burnout after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:302–9.

Pai ALH, Swain AM, Chen FF, et al. Screening for family psychosocial risk in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with the psychosocial assessment tool. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:1374–81.

Polomeni A, Lapusan S, Bompoint C, Rubio MT, Mohty M. The impact of allogeneic-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on patients’ and close relatives’ quality of life and relationships. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;21:248–56.

Posluszny DM, Bovbjerg DH, Syrjala KL, Agha M, Dew MA. Correlates of anxiety and depression symptoms among patients and their family caregivers prior to allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant for hematological malignancies. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:591–600.

Riva R, Forinder U, Arvidson J, et al. Patterns of psychological responses in parents of children that underwent stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology. 2014;23:1307–13.

Rodday AM, Terrin N, Chang G, Parsons SK. Performance of the parent emotional functioning (PREMO) screener in parents of children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1427–33.

Sands SA, Mee L, Bartell A, et al. Group-based trajectory modeling of distress and well-being among caregivers of children undergoing hematopoetic stem cell transplant. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42:283–95.

Sannes TS, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Natvig CL, Laudenslager ML. Intraindividual cortisol variability and psychological functioning in caregivers of hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Psychosom Med. 2016;78:242–7.

Sannes TS, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Natvig CL, Brewer BW, Simoneau TL, Laudenslager ML. Caregiver sleep and patient neutrophil engraftment in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant: a secondary analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41:77–85.

Simoneau TL, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Natvig C, et al. Elevated peri-transplant distress in caregivers of allogeneic blood or marrow transplant patients. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2064–70.

Vrijmoet-Wiersma CMJ, Egeler RM, Koopman HM, Bresters D, Norberg AL, Grootenhuis MA. Parental stress and perceived vulnerability at 5 and 10 years after pediatric SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1102–8.

Ward J, Fogg L, Rodgers C, Breitenstein S, Kapoor N, Swanson BA. Parent psychological and physical health outcomes in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer Nurs. 2018;42(6):448–57.

Fladeboe K, King K, Kawamura J, et al. Featured article: caregiver perceptions of stress and sibling conflict during pediatric cancer treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2018;43:588–98.

He S, You LM, Zheng J, Bi YL. Uncertainty and personal growth through positive coping strategies among chinese parents of children with acute leukemia. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:205–12.

Iwai N, Shimada A, Iwai A, Yamaguchi S, Tsukahara H, Oda M. Childhood cancer survivors: anxieties felt after treatment and the need for continued support. Pediatr Int. 2017;59:1140–50.

Nam GE, Warner EL, Morreall DK, Kirchhoff AC, Kinney AY, Fluchel M. Understanding psychological distress among pediatric cancer caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:3147–55.

Olagunju AT, Sarimiye FO, Olagunju TO, Habeebu MY, Aina OF. Child’s symptom burden and depressive symptoms among caregivers of children with cancers: an argument for early integration of pediatric palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. 2016;5:157–65.

Ortega-Ortega M, Montero-Granados R, Romero-Aguilar A. Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with informal care in hematologic malignancy patients: a study based on different phases of the treatment, Spain. Rev Esp Salud Publ. 2015;89:201–13.

Patel SK, Wong AL, Cuevas M, Van Horn H. Parenting stress and neurocognitive late effects in childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1774–82.

Sulkers E, Tissing WJ, Brinksma A, et al. Providing care to a child with cancer: a longitudinal study on the course, predictors, and impact of caregiving stress during the first year after diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2015;24:318–24.

Teixeira RJ, Pereira MG. Psychological morbidity, burden, and the mediating effect of social support in adult children caregivers of oncological patients undergoing chemotherapy. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1587–93.

Hong D, Zhou C, He H, Wang Y, Lu J, Hu S. A 10-year follow-up survey of treatment abandonment of children with acute myeloid leukemia in Suzhou, China. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016;38:437–42.

Denzen EM, Thao V, Hahn T, et al. Financial impact of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation on patients and families over 2 years: results from a multicenter pilot study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:1233–40.

Farnia S, Ganetsky A, Silver A, et al. Challenges around access to and cost of life-saving medications after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for medicare patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23:1387–92.

Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Hahn T, et al. Pilot study of patient and caregiver out-of-pocket costs of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:865–71.

Bona K, Dussel V, Orellana L, et al. Economic impact of advanced pediatric cancer on families. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:594–603.

Dussel V, Bona K, Heath JA, Hilden JM, Weeks JC, Wolfe J. Unmeasured costs of a child’s death: perceived financial burden, work disruptions, and economic coping strategies used by American and Australian families who lost children to cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1007–13.

Fluchel MN, Kirchhoff AC, Bodson J, et al. Geography and the burden of care in pediatric cancers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1918–24.

Ghatak N, Trehan A, Bansal D. Financial burden of therapy in families with a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: report from north India. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:103–8.

Hollenbeak CS, Short PF, Moran J. The implications of cancer survivorship for spousal employment. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:226–34.

Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016;122:283–9.

Ortega-Ortega M, Del Pozo-Rubio R. Catastrophic financial effect of replacing informal care with formal care: a study based on haematological neoplasms. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20:303–16.

Ortega-Ortega M, Montero-Granados R, Jimenez-Aguilera JD. Differences in the economic valuation and determining factors of informal care over time: the case of blood cancer. Gac Sanit. 2018;32:411–7.

Rativa Velandia M, Carreno Moreno SP. Family economic burden associated to caring for children with cancer. Invest Educ Enferm. 2018;36: e07.

Santos S, Crespo C, Canavarro MC, Alderfer MA, Kazak AE. Family rituals, financial burden, and mothers’ adjustment in pediatric cancer. J Fam Psychol. 2016;30:1008–13.

Sneha LM, Sai J, Ashwini S, Ramaswamy S, Rajan M, Scott JX. Financial burden faced by families due to out-of-pocket expenses during the treatment of their cancer children: an Indian perspective. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38:4.

Warner EL, Kirchhoff AC, Nam GE, Fluchel M. Financial burden of pediatric cancer for patients and their families. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:12–8.

Badia P, Hickey V, Flesch L, et al. Quality improvement initiative to reduce nighttime noise in a transplantation and cellular therapy unit. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(9):1844–50.

Bevans M, Castro K, Prince P, et al. An individualized dyadic problem-solving education intervention for patients and family caregivers during allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a feasibility study. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:E24-32.

Bevans M, Wehrlen L, Castro K, et al. A problem-solving education intervention in caregivers and patients during allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Health Psychol. 2014;19:602–17.

Devine KA, Manne SL, Mee L, et al. Barriers to psychological care among primary caregivers of children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2235–42.

Fauer AJ, Hoodin F, Lalonde L, et al. Impact of a health information technology tool addressing information needs of caregivers of adult and pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:2103–12.

Kim W, Bangerter LR, Jo S, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a 3-day group-based digital storytelling workshop among caregivers of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation patients: a mixed-methods approach. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:2228–33.

Kroemeke A, Knoll N, Sobczyk-Kruszelnicka M. Dyadic support and affect in patient-caregiver dyads following hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a diary study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87:541–50.

Langer SL, Yi JC, Storer BE, Syrjala KL. Marital adjustment, satisfaction and dissolution among hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients and spouses: a prospective, five-year longitudinal investigation. Psychooncology. 2010;19:190–200.

Langer SL, Kelly TH, Storer BE, Hall SP, Lucas HG, Syrjala KL. Expressive talking among caregivers of hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors: acceptability and concurrent subjective, objective, and physiologic indicators of emotion. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30:294–315.

Langer SL, Porter LS, Romano JM, Todd MW, Lee SJ. A couple-based communication intervention for hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors and their caregiving partners: feasibility, acceptability, and change in process measures. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:1888–95.

Laudenslager ML, Simoneau TL, Philips S, Benitez P, Natvig C, Cole S. A randomized controlled pilot study of inflammatory gene expression in response to a stress management intervention for stem cell transplant caregivers. J Behav Med. 2016;39:346–54.

Manne S, Mee L, Bartell A, Sands S, Kashy DA. A randomized clinical trial of a parent-focused social-cognitive processing intervention for caregivers of children undergoing hematopoetic stem cell transplantation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:389–401.

Ouseph R, Croy C, Natvig C, Simoneau T, Laudenslager ML. Decreased mental health care utilization following a psychosocial intervention in caregivers of hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Ment Illn. 2014;6:5120.

Vinci C, Reblin M, Jim H, Pidala J, Bulls H, Cutolo E. Understanding preferences for a mindfulness-based stress management program among caregivers of hematopoietic cell transplant patients. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;33:164–9.

Barrera M, Hancock K, Rokeach A, et al. Does the use of the revised psychosocial assessment tool (PATrev) result in improved quality of life and reduced psychosocial risk in Canadian families with a child newly diagnosed with cancer? Psychooncology. 2014;23:165–72.

Creedle C. The impact of a carepartner program on two inpatient oncology units: 1052755 [Article]. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:E153.

Kubo A, Altschuler A, Kurtovich E, et al. A pilot mobile-based mindfulness intervention for cancer patients and their informal caregivers. Mindfulness (NY). 2018;9:1885–94.

Kubo A, Kurtovich E, McGinnis M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of mHealth mindfulness intervention for cancer patients and informal cancer caregivers: a feasibility study within an integrated health care delivery system. Integr Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1534735419850634.

Oh YS. Communications with health professionals and psychological distress in family caregivers to cancer patients: a model based on stress-coping theory. Appl Nurs Res. 2017;33:5–9.

Pailler ME, Johnson TM, Zevon MA, et al. Acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy of a supportive group intervention for caregivers of newly diagnosed leukemia patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2015;33:163–77.

Rosenberg-Yunger ZR, Granek L, Sung L, et al. Single-parent caregivers of children with cancer: factors assisting with caregiving strains. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2013;30:45–55.

Nijboer C, Triemstra M, Tempelaar R, Sanderman R, van den Bos GA. Measuring both negative and positive reactions to giving care to cancer patients: psychometric qualities of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA). Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1259–69.

Weitzner MA, Jacobsen PB, Wagner H Jr, Friedland J, Cox C. The Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) scale: development and validation of an instrument to measure quality of life of the family caregiver of patients with cancer. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:55–63.

Rhee YS, Shin DO, Lee KM, et al. Korean version of the caregiver quality of life index-cancer (CQOLC-K). Qual Life Res. 2005;14:899–904.

Bektas HA, Ozer ZC. Reliability and validity of the caregiver quality of life index-cancer (CQOLC) scale in Turkish cancer caregivers. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:3003–12.

Lafaye A, De Chalvron S, Houédé N, Eghbali H, Cousson-Gélie F. The caregivers quality of life cancer index scale (CQoLC): an exploratory factor analysis for validation in French cancer patients’ spouses. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:119–22.

Duan J, Fu J, Gao H, et al. Factor analysis of the Caregiver Quality of Life Index-Cancer (CQOLC) scale for Chinese cancer caregivers: a preliminary reliability and validity study of the CQOLC-Chinese version. PLoS One. 2015;10: e0116438.

National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Acute Myeloid Leukemia. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/amyl.html. Accessed May 10, 2020.

Schulz R, Eden J, editors. Families caring for an aging America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2016.

Greenfield JC, Hasche L, Bell LM, Johnson H. Exploring how workplace and social policies relate to caregivers’ financial strain. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2018;61:849–66.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Caregiving for family and friends—a public health issue. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/agingdata/docs/caregiver-brief-508.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2020

Merrill. The journey of caregiving: honor, responsibility and financial complexicity. https://mlaem.fs.ml.com/content/dam/ML/Registration/family-and-retirement/ML_Caregiving_WP_v02g.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2020.

Chari AV, Engberg J, Ray KN, Mehrotra A. The opportunity costs of informal elder-care in the United States: new estimates from the American Time Use Survey. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:871–82.

Virtue SM, Manne SL, Mee L, et al. Psychological distress and psychiatric diagnoses among primary caregivers of children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant: an examination of prevalence, correlates, and racial/ethnic differences. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:620–6.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work, the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access fees were funded by Amgen Inc.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The authors thank Zeinab Abbas (Amgen Ltd, UK, at the time of the study) for her contribution to the development of the manuscript. Editorial support for development of this manuscript was provided by Erin P. O’Keefe and Rick Davis at ICON plc (North Wales, PA), and funded by Amgen Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship in this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Emre Yucel prepared the research questions, contributed significantly to the protocol and its execution, arranged and organized the publications in categories as described in the methods, and contributed significantly to the overall reporting and writing of the manuscript. Shiyu Zhang provided significant content to the protocol and several drafts of the manuscript, created the search key terms, executed searches in databases, and collated findings in relevant tables and shells. Sumeet Panjabi contributed significantly to protocol writing and organization, drafting and reviewing the manuscript.

Disclosures

Emre Yucel held Amgen stock during the research and writing of this TLR; Emre Yucel was employed by Amgen at the time of the development of this manuscript and is currently at Bristol Myers Squibb, Lawrenceville (Princeton Pike), NJ. Shiyu Zhang worked on this project when she did her summer internship at Amgen in 2019, and was paid as an intern. Sumeet Panjabi was employed by Amgen at the time of development of this manuscript; Sumeet Panjabi is currently at Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., South San Francisco, CA.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yucel, E., Zhang, S. & Panjabi, S. Health-Related and Economic Burden Among Family Caregivers of Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia or Hematological Malignancies. Adv Ther 38, 5002–5024 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01872-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01872-x