Abstract

In order to offer early and accessible treatment for adolescents with depression, brief and effective treatments in adolescents’ everyday surroundings are needed. This randomized controlled trial studied the preliminary effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of interpersonal counseling (IPC) and brief psychosocial support (BPS) in school health and welfare services. The study was conducted in the 28 lower secondary schools of a large city in Southern Finland, randomized to provide either IPC or BPS. Help-seeking 12–16-year-old adolescents with mild-to-moderate depression, with and without comorbid anxiety, were included in the study. Fifty-five adolescents received either 6 weekly sessions of IPC or BPS and two follow-up sessions. Outcome measures included self- and clinician-rated measures of depression, global functioning, and psychological distress/well-being. To assess feasibility and acceptability of the treatments, adolescents’ and counselors’ treatment compliance and satisfaction with treatment were assessed. Both treatments were effective in reducing depressive disorders and improving adolescents’ overall functioning and well-being. At post-treatment, in both groups, over 50% of adolescents achieved recovery based on self-report and over 70% based on observer report. Effect sizes for change were medium or large in both groups at post-treatment and increased at 6-month follow-up. A trend indicating greater baseline symptom severity among adolescents treated in the IPC-providing schools was observed. Adolescents and counselors in both groups were satisfied with the treatment, and 89% of the adolescents completed the treatments and follow-ups. This trial suggests that both IPC and BPS are feasible, acceptable, and effective treatments for mild-to-moderate depression in the school setting. In addition, IPC seems effective even if comorbid anxiety exists. Our study shows that brief, structured interventions, such as IPC and BPS, are beneficial in treating mild-to-moderate depression in school settings and can be administered by professionals working at school.

Trial registrationhttp://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT03001245.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A marked increase in the incidence of depressive symptoms and disorders occurs rapidly after the age of 13 (Hankin et al., 1998; Thapar, Collishaw, Pine, & Thapar, 2012). In Finland, approximately 17% of adolescent females and 8% of adolescent males suffer from moderate or severe depressive symptoms (Savioja, Helminen, Fröjd, Marttunen, & Kaltiala-Heino, 2015). As many as a fifth of adolescents experience a depressive episode by the end of the adolescent period (Gore et al., 2011). Typically, major depressive disorder (MDD) in adolescence is associated with recurrent episodes, need for psychiatric treatment (Avenevoli, Swendsen, He, Burstein, & Merikangas, 2015), impairments in school functioning as well as in family and social relationships (Birmaher et al., 1996; Flament, Cohen, Choquet, Jeammet, & Ledoux, 2001), and elevated risk of suicide and self-harm (e.g., Hawton, Saunders, & O’Connor, 2012). In addition, alcohol or substance abuse or dependence is frequently associated with depression (e.g., Brière, Rohde, Seeley, Kleind, & Lewinsohn, 2014; Churchill & Farrel, 2017). MDD is as well frequently comorbid with anxiety disorders (Garber & Weersing, 2010). Depression comorbid with anxiety disorders is also likely to be more chronic and resistant to change (Jacobson & Newman, 2017).

Mental health problems, including depression, are largely undertreated among adolescents (Haarasilta, Marttunen, Kaprio, & Aro, 2003; Jörg et al., 2016; Merikangas et al., 2010). In Finland, practically all adolescents attend public secondary schools (Official Statistics of Finland, 2017); thus, the school context offers a good opportunity for screening and early intervention for depression (Leaf et al., 1996; Werner-Seidler, Perry, Calear, Newby, & Christensen, 2017; Williams, O’Connor, Eder, & Whitlock, 2009). As service users, adolescents identify easy access and minimal disruption to school work as important criteria for their engagement in mental health treatment (Persson, Hagquist, & Michelson, 2017).

According to meta-analyses, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT-A) are effective treatments for depression in adolescents (Pu et al., 2017; Weisz et al., 2013, 2017; Zhou et al., 2015). Although adaptations of these treatments have shown promise in reducing depressive symptoms in population-based student samples (Clarke et al., 1995; Horowitz, Garber, Ciesla, Young, & Mufson, 2007; La Greca, Ehrenreich-May, Mufson, & Chan, 2016; Ruffolo & Fischer, 2009; Young, Mufson, & Davies, 2006a; Young, Mufson & Gallop, 2010), more research is needed to establish the effectiveness of such treatments for adolescents with mild or moderate clinical depression in naturalistic settings (e.g., Arora, Collins, Dart, Hernández, Fetterman, & Doll, 2019; Mufson, 2010; Mufson, Pollack, Moreau, & Weissman, 2004a).

IPT-A is adapted from the adult-based interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) (Klerman Weissman, Rounsaville, & Chevron, 1984; Markowitz & Weissman, 2012). A central theoretical principle behind interpersonal therapy is that there is a bidirectional link between interpersonal functioning and depressive symptoms. Specifically, as adolescents learn how to solve their interpersonal problems in treatment, their mood gradually improves (Mufson et al., 2004a; Mufson, Pollack, Wickramaratne, Nomura, Olfson, & Weissman, 2004b). As interpersonal difficulties are likely to drive psychopathology in adolescence (Rueter, Scaramella, Wallace, & Conger, 1999), IPT-A may be particularly well suited to as a treatment option (Gunlicks-Stoessel, Mufson, Jekal, & Turner, 2010; Horowitz et al., 2007; Thapar et al., 2012). In school-based trials, IPT-A has been more effective than treatment as usual (TAU) for depression (Mufson et al., 2004b) and for reducing adolescents’ suicidal ideation and hopelessness (Tang, Jou, Ko, Huang, & Yen, 2009), even when adolescents have comorbid anxiety symptoms (Young, Mufson, & Davies, 2006b).

However, the 12-session IPT-A treatment may be difficult to implement due to limitations imposed by the school curriculum, such as a limited recruitment period or restricted time to conduct sessions (Girio-Herrera, Ehrlich, Danzi & La Greca, 2019). Furthermore, professionals who work at school may have multiple and competing tasks, and high workload (Mufson, 2010). For example, in Finland, school social workers and school psychologists typically work in multiple schools and are responsible for about 1000 students (Hietanen-Peltonen, Vaara, & Laitinen, 2019a, b). Due to such obstacles, evidence-based interventions have been modified to include fewer sessions (Mufson, Yanes-Lukin, & Anderson, 2015; Weissman et al., 2014; Wood, Harrington, & Moore, 1996). Most modifications assume that focusing on only the key therapeutic components might lead to effectiveness comparable to that of the original treatments (see Mufson et al., 2015).

The present study examined the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of interpersonal counseling (IPC), for treating adolescent depression in a school setting. IPC is a brief (typically up to six sessions) treatment derived directly from IPT (Weissman & Klerman, 1993; Weissman, Markowitz, & Klerman, 2018). An advantage of IPC is that also professionals other than healthcare personnel can be trained to deliver it (Weissman et al., 2014). Internationally, IPC has mainly been used with adults in community settings (e.g., Kontunen et al., 2016; Menchetti et al., 2010, 2014). For example, in a Finnish study, Kontunen et al. (2016) found IPC delivered by nurses in a community health and welfare service was equally effective in improving major depressive disorder (mild or moderate) as the full IPT. A recent study (Wilkinson, Cestaro, & Pinchin, 2018) found IPC to be a feasible intervention, leading to a decrease in depressive symptoms among adolescents treated by youth workers. A novel and important contribution of the present study is to extend the work on IPC to the treatment of clinical depression among adolescents in school settings.

All Finnish schools have their own school health and welfare services (SHWSs). The main task of this service is to support the well-being of students and well-being of the whole school community by providing both individual- and community-focused interventions (Student Welfare Act 1287/2013). In SHWS, school psychologists, social workers, and nurses (hereafter collectively referred to as school workers, SWs) traditionally have based their practice on the prevention of mental health problems, offering supportive care on an as-needed basis, and counseling adolescents when they face psychosocial problems (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, 2009). Furthermore, the work duties of SWs vary by profession (e.g., annual physical examinations are provided by school nurses), and the treatment of mental health problems is only a part of each professional group’s duties. As the Finnish SHWS has followed a broad prevention agenda, evidence-based, structured interventions targeting mental health disorders have not been widely used despite a growing recognition of the need for early interventions (see Haravuori et al., 2017; Ranta et al., 2018).

In summary, there is a clear need to develop and implement effective and brief treatments for adolescent depression in schools, as well as in other service contexts, that provide youth with easy access to treatment (Persson et al., 2017). To our knowledge, no school-based trials examining the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of IPC have been reported. Thus, the aim of the present study was to assess the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of IPC as compared with brief psychosocial support (BPS) in the Finnish SHWS in a pilot randomized controlled trial.

Methods

Participants

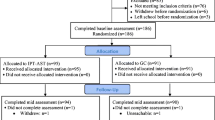

Fifty-five 12–16-year-old students (43 girls and 12 boys) were recruited from the 28 public lower secondary schools of a large city in Southern Finland and began either IPC or BPS (see Fig. 1) during September 2016 to April 2017. Fifty of the adolescents were born in Finland, and all spoke fluent Finnish. The treatment-providing SWs, recruited from local secondary school SHWS, were school psychologists (n = 14), school social workers (n = 15), or school nurses (n = 7) by profession. In addition, one community health and welfare service for adolescents with a target of treating mild or moderate psychosocial problems was included as a study cite, including one nurse and one psychologist.

Study design and flowchart. Flowchart from the study. SHWS School Health and Welfare Services, BPS brief psychosocial support, IPC interpersonal counseling, R-BDI Finnish modification of the 13-item Beck Depression Inventory, K-SADS the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children; AUDIT Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; YP-CORE Young Person’s Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation; ADRSc Adolescent Depression Rating Scale clinician version; BDI Beck Depression Inventory; CGAS Children’s Global Assessment Scale; Excluded if severe major depression; actively suicidal; a current diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence; severe primary anxiety or other mental disorders causing severe impairment; schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders. 1One primary level unit providing psychosocial treatments for youth with symptoms on corresponding level than among those in the SHWS was included and randomized as one school/study site

Procedure

Researchers and managers from University Hospital and the SHWS collaborated to conduct the IPC implementation project from 2016 to 2017. IPC training was delivered in two waves. All SWs in sites randomized to IPC received their training in August 2016 and delivered IPC through the school year 2016–2017. SWs in BPS sites delivered BPS through the school year 2016–2017 and received IPC training after the data collection period ended, in August 2017.

Randomization

The study was based on a cluster-randomization design: The participating schools (sites) were randomized to provide either IPC or BPS. All adolescents participating in the study within the same school received the same intervention. Twenty-seven schools and one community health and welfare service were randomized to receive either IPC or BPS by randomly and blindly pulling a card containing the name of the school/site from a container.

As a result of the randomization, 12 schools and one community health and welfare service were defined as IPC sites. Correspondingly, 15 schools were defined as BPS sites. However, one SW worked in two secondary schools, of which one was randomized to provide IPC and the other BPS. As she was trained in IPC, she provided IPC in both schools.

Adolescents treated in schools and in the community health and welfare service did not differ on the two primary outcome measures of depression at baseline (Beck Depression Inventory = t(4.02, 53) = 1.14, p = .26; Adolescent Depression Rating Scale = t(2.70, 52) = .75, p = .46).

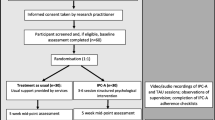

Recruitment

As our intention was to study the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of the treatments in a naturalistic setting, the recruitment process followed the normal pathways available for adolescents to obtain help or support from the SHWS (see Fig. 2). Students informally identified as experiencing problems possibly related to depression by SWs in SHWS were first screened for depression with a short depression measure; those who screened positive and consented were referred for a diagnostic interview. No incentives were given for participation. All participating students and their parents/legal guardians provided their written informed consent.

Referral process. Note: SW school worker, SHWS student health and welfare service, R-BDI Finnish modification of the Beck Depression Inventory, K-SADS the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children. *As illustrated in the upper part of the figure, there are several routes to obtain help for an adolescent who experiences problems in mental health or well-being. In addition, a student may be referred to IPC/BPS based on the results of screenings of mood conducted by the school nurse. Such screenings are conducted with specific age cohorts (e.g., eighth graders) each year, but not with all students

Diagnostic Evaluation

A structured psychiatric interview, the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS-PL, Kaufman et al., 1997), was administered by a clinical psychologist to confirm adolescents met DSM-5 inclusion criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and that no exclusion criteria were present (see Figs. 1, 2). Potential comorbidity with alcohol abuse was assessed with a self-report measure, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Reinert & Allen, 2002).

Inclusion in the trial was based on data from the K-SADS-PL and AUDIT, and, when needed for diagnostic consideration, consultation with a psychiatrist. All adolescents who received a diagnosis of mild (5–6/9 DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depression, mild functional impairment) or moderate (6–7/9 DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depression, moderate functional impairment) major depressive disorder, dysthymia, or depressive disorder not otherwise specified, according to the DSM-5 definitions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), were included in the study (see Table 1).

The following were criteria for exclusion from the study: severe major depression (8–9/9 DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depression, severe functional impairment); acutely suicidality; current diagnosis of alcohol or other substance abuse or dependence; primary and severe anxiety disorder or other mental disorder causing severe impairment (e.g., being unable to go to school); and a psychotic disorder. Excluded adolescents were referred to specialized psychiatric care. Adolescents also were excluded if they were already in mental health treatment elsewhere or if there was an acute need for child protection services. In total, four adolescents met the exclusion criteria: one with severe major depression, one acutely referred to child protection services, one with a primary and severe anxiety disorder, and one with a psychotic disorder. In addition, two adolescents declined to participate in the study after the diagnostic evaluation (see Fig. 1).

Diagnostic evaluation and all other study assessments were administered again at 3- and 6-month follow-up by two clinical research psychologists trained to use the interview and other measures used in the study. Diagnostic remission was defined as not fulfilling the criteria for a depressive disorder at both follow-ups. The clinicians performing the diagnostic evaluations were not blinded to the treatment condition.

Treatments

Both IPC and BPS treatments took place within the school buildings, in the offices of the SWs who provided the treatments, with the exception of the community health and welfare service, which is located in the community. As students have right to use SHWS during school days, they had an option to choose whether the treatments took place during school days, or after school days.

Interpersonal Counseling (IPC)

IPC is a brief, time-limited, and individual-based treatment (3–8 sessions) focusing on current symptoms of depression in an interpersonal context. It is a shortened version of IPT and was originally designed to be administered by non-mental health professionals for patients with mild depression (Weissman et al., 2014). The goals of IPC are to reduce the individuals’ depressive symptoms and improve interpersonal functioning by relating the symptoms to one or more of four life stressors (grief, role disputes, role transitions, and loneliness/isolation) and by developing strategies for dealing with these stressors. Patients are helped to recognize the triggers of depression and to identify the resources that they have (Weissman et al., 2014).

In this study, IPC was delivered in six 45-minute sessions over a 6–12-week period, following the structure of IPC as delineated by Judd, Weissman, Davis, Hodgins, and Piterman (2004). IPC involves three phases: Firstly, psychoeducation on depression is provided; secondly, active therapeutic work within the agreed focus area is carried out; and finally, discussion on progress and on future challenges is undertaken. In the middle phase, IPC-specific techniques (i.e., clarification, summaries, questions, communication analysis, decision analysis, and role-play) are used. The treatment was administered according to the procedures specified in the IPC treatment manual (Weissman & Verdeli, 2013), and its adaptation for adolescents (Wilkinson & Cestaro, 2015). A list of assessed therapeutic components of IPC can be found online (see Online Resource 2).

Brief Psychosocial Support (BPS)

BPS is based on the methods and techniques used by SWs in their routine work. However, routine work in SHWS in Finland has traditionally focused on prevention and supporting well-being of students, not on assessing and treating mental health disorders or evaluating psychosocial functioning (Haravuori et al., 2017). To deliver BPS, the SWs were instructed to assess, repeatedly monitor, and target symptoms of depression in addition to using their routine skills to support the students to cope with symptoms of depression, and to limit the BPS to six sessions over 6–12 weeks.

Thus, BPS represents an enhanced, more intensive, and more focused version of the routine counseling provided by professionals working in the Finnish SHWSs. To ensure comparability across treatments, BPS was delivered with the same frequency and session duration as IPC, both interventions included also the same assessment measures. (See detailed information about the study design from Fig. 1.)

Clinician Training

Prior to both IPC or BPS, all participating SWs were given a one-day training workshop on the identification and assessment of depression and the use of all assessment measures included in the trial and were instructed to systematically and repeatedly assess and monitor symptoms of depression in their adolescent clients.

The IPC training consisted of 3 days of didactic and practical training and ongoing clinical supervision. Didactic training included a one-day tutorial on the basic principles of IPC and a two-day clinical workshop on the theory and principles behind interpersonal therapy and the clinical use of IPC techniques with adolescents. The IPC treatment manual adapted for adolescents (Wilkinson & Cestaro, 2015) was used in the training. Clinical method-specific supervision was provided in groups of 5–6 IPC counselors every second week (lasting 2.5 h) for the duration of the trial. Each IPC counselor discussed his/her case/cases during supervision. Also, general discussion about the IPC process was allowed. Supervisors were clinicians from the psychiatric special healthcare services (University Hospital) trained in IPT-A and who had at least a year’s experience in delivering IPT-A. Supervisors also attended the IPC training. On an as-needed basis, the trainee IPC counselors could receive extra supervision by phone or via e-mail to answer short, specific questions in between supervision sessions, but the amount of extra contact was not tabulated.

Measures

Screening, Diagnostic, and Outcome Measures

The screening measure used was the Finnish modification of the 13-item revised Beck Depression Inventory, R-BDI (Beck & Beck, 1972; Raitasalo, 2007). It is widely used in the Finnish SHWSs for screening depressive symptoms. The items are scored 0–3 (with 3 indicating the greatest severity) and then summed, giving a total score ranging from 0 to 39. Cronbach’s alpha for the 13 items in this study population was .68.

The diagnostic evaluation used the K-SADS-PL (Kaufman et al., 1997). The current, updated K-SADS-5 version was used; it is a semi-structured interview covering both lifetime and current mental disorders according to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. The previous DSM-IV version of this instrument has been found to be a valid measure of adolescents’ affective and anxiety disorders (Kaufman et al., 1997; Lauth, Arnkelsson, Magnússon, Skarphéðinsson, Ferrari, & Pétursson, 2010). In addition, adolescents completed AUDIT (Reinert & Allen, 2002), which is a 10-item questionnaire measuring alcohol use and/or alcohol-related problems. The AUDIT has been reported to have acceptable psychometric properties when used with adolescents (Liskola et al., 2018; Santis et al., 2009).

The two primary treatment outcome measures defined in the trial protocol were: (a) self-reported change in depression symptoms as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1961) and (b) clinician-reported change in depression symptoms as measured by the Adolescent Depression Rating Scale, clinician version (ADRSc; Revah-Levy, Birmaher, Gasquet, & Falissard, 2007). The BDI is a widely used 21-item questionnaire for depression and also a well-studied measure for depressive symptoms among adolescents (Brooks & Kutcher, 2001; Myers & Winters, 2002). The items are rated using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, with a range of total scores from 0 to 63. A total score of 10 or more is generally used to indicate clinical depression (Beck, Steer, & Carbin, 1988). The ADRSc was rated by the SWs delivering the IPC or BPS treatments; it is a 10-item rating scale specifically designed to assess the severity of symptoms of depression in adolescents. It measures both the internal state of depression (e.g., irritability, negative perceptions of self) and external manifestations related to depression (e.g., investment in school, relationship withdrawal) (Revah-Levy et al., 2007). Items are rated from 0 to 6 (with 6 indicating the greatest severity), and the scores are summed (range 0–60). The optimal cutoff for a clinical diagnosis of depression is a total score of 15. The ADRSc has acceptable psychometric properties with good convergent, discriminant, and factorial validity, and good internal consistency (Revah-Levy et al., 2007). In this study population, Cronbach’s alpha reliability was .89 for the BDI and .80 for the ADRSc.

The secondary treatment outcomes were: (a) change in adolescent self-reported psychological distress/well-being as measured by the Young Person’s Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (YP-CORE; Twigg et al., 2009) and (b) change in global psychosocial functioning as measured by the clinician-rated Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Shaffer et al., 1983). The YP-CORE is a commonly used, 10-item measure for the assessment of clinical change among young people within counseling and treatment settings. It has been shown to possess good psychometric properties, to be reliable and sensitive to change, and it is well accepted by young people (Gergov et al., 2017; Twigg et al., 2015). It assesses subjective well-being, psychological symptoms and problems, overall functioning and social interactions, and risk of self and others during the previous week. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all; 4 = most or all of the time), and the scores are summed (range 0–40). The recommended cutoff for clinically significant impairment is 14. The CGAS is a well-established and widely used rating scale for the measurement of adolescents’ overall functioning. It is reliable between raters and across time, and it has demonstrated good convergent validity (Bird et al., 1996). The maximum score of 100 indicates superior functioning in key life contexts: at home, at school, with peers; the minimum score of 1 indicates the loss of function on these functional domains and the need for constant supervision. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability was .74 for the YP-CORE and .84 for the CGAS.

Feasibility and Acceptability Assessments

For both treatments, feasibility was assessed by evaluating adolescents’ treatment engagement as evidenced by completing treatment, session attendance, and attendance at follow-ups. In addition, IPC counselors’ rate of attendance at supervision sessions was evaluated as an indicator of feasibility. These indicators are directly related to administering the treatments and supervision and do not capture the wider organizational aspects of feasibility, which are related to how the treatments can be arranged within a given agency.

Adolescents’ perception of their treatment, as treatment satisfaction, perception of change, and collaboration with the counselor was assessed as indicator of treatment acceptability (Proctor et al., 2011). A subsample of 17 adolescents (approximately 25% of the study sample) were interviewed either face to face (n = 9) or by telephone (n = 8). A structured questionnaire, modified from the Elliot Client Change Interview (Elliot, 2012; Elliot & Rodgers, 2008), was used. The subsample consisted of all adolescents who reached 3-month post-treatment time point between March and April 2017. The interviews were conducted at the 3-month follow-up by two psychology students blind to the treatment condition and trained to conduct the interview. The questions covered the adolescents’ overall satisfaction with the treatment (“How has it felt to be in counselling?”); their perception of change since the treatment began (e.g., “What changes, if any, have you noticed in yourself since counselling started?”); questions about their perception of the different aspects of the therapeutic process (e.g., “What has been helpful about counselling so far?” or “What kinds of things about the counselling have been hindering, unhelpful, negative or disappointing for you?”); and the research process (e.g., “What has it been like to be involved in this research?”). Questions were added that covered collaboration with the counselor (“How collaborative was your work with your counselor?”; “Did you feel your feelings and thoughts were understood and accurately perceived by the counselor?”; “Did you feel you were understood by the counselor?”; “Did your relationship with your counselor change during meetings?”) and the ending of treatment (“Do you still need treatment?”; if new treatment was begun: “How do you feel about the new treatment”?). For the IPC group, one set of questions were added that covered the use of the IPC manual (“What did you think about homework?”; “What was helpful about this procedure?”; “Was there anything that didn’t work?”).

The acceptability of IPC and BPS for the SWs was evaluated using a structured questionnaire developed for the study (see Table 4). Seven questions assessed SW’s satisfaction with the treatment, the assessment instruments, and the implementation process in the school. In addition, one question was presented to the BPS counselors about the need of supervision; four questions were presented to the IPC counselors about the IPC training and supervision. Ratings were given on a 4-point scale.

Assessment of Implementation Fidelity

To assess the fidelity of implementation, the IPC counselors’ adherence to clinical principles of IPC was evaluated by supervisors’ ratings; these ratings were based on the trainees’ casework presented in the supervision sessions. A modification of the IPC Competencies List (Wilkinson, 2015) was used (for the original version see IPT Audio Recording Rating Scale, Law, 2011). The IPC Competencies List contains 34 competencies divided into generic therapeutic competencies (10 items), basic IPC competencies (13 items), IPC-specific techniques (5 items), and overarching therapeutic competencies (3 items) and IPC-related (3 items). In this trial, only 20 competencies related to IPC were assessed (e.g., Knowledge of basic principles and rationale for IPC; Ability to use decision analysis; Ability to balance being focused and maintaining the therapeutic alliance). (See list of assessed therapeutic components in Online Resource 2.) These were selected because the main focus of interest was adherence to the method-specific principles of IPC and because of the limited time resources available to the supervisors. Supervisors rated the trainee IPC counselors’ adherence to clinical principles of IPC on a 5-point scale: 0 = skill/technique was not used/was not relevant at this point, 1 = skill/technique was not mastered at all, 2 = skill/technique was mastered to a small amount, 3 = skill/technique was mastered relatively well, 4 = skill/technique was mastered well.

Statistical Analysis

Adolescents in the IPC and BPS groups were compared on baseline characteristics (age, gender, class, average grade in school, living in a single parent home, socioeconomic status), baseline values of outcome measures (BDI, ADRSc, YP-CORE, and CGAS), and the categorical presence of a depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, and other psychiatric disorders. Comparisons used Chi-square tests for categorical data and independent-samples t-tests for continuous data.

All analyses used an intent-to-treat design. Overall efficacy of both IPC and BPS was examined by comparing the baseline scores of the predefined primary outcome measures (BDI and ADRSc) with their respective scores immediately after the treatment, and at 3-month and 6-month follow-ups, using effect sizes. Secondary analyses compared YP-CORE and CGAS scores at baseline with their respective scores at treatment termination, and at 3-month and 6-month follow-ups, respectively. Effect sizes were estimated using Cohen’s d and were defined as small (d > .20), medium (d > .50), and large (d > .80) (Cohen, 1988).

Relative effectiveness of IPC and BPS was examined by using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with intervention type (IPC or BPS) as the between-level factor and time (baseline, treatment endpoint, 3-month and 6-month follow-ups) as the within-level factor. Separate ANOVAs were conducted for all outcome measures: BDI, ADRSc, YP-CORE, and CGAS.

Clinical response was defined as having at least 50% symptom reduction in the primary outcome measures (BDI and ADRSc). This definition of clinical response is the standard definition used in many psychiatric efficacy and effectiveness studies (e.g., Pu et al. 2017). Clinical recovery was defined as absence of depressive symptoms or the presence of minimal depressive symptoms (score < 10 in BDI; score < 15 in ADRSc). Data were analyzed using Chi-square tests, counting relative risk and odds ratios. Missing data for dropout adolescents were imputed by carrying the last observation forward until the 6th session if the adolescent had at least one assessment in a scale after baseline.

Feasibility of the treatments for the adolescents was examined by calculating the adolescents’ completion rate and attendance rate for planned sessions for both treatments. In addition to assess feasibility, IPC counselors’ attendance rate for IPC supervision sessions was counted. The acceptability of IPC and BPS for the SW’s was evaluated by calculating item means of a structured questionnaire developed for the study. To ensure that IPC was implemented with fidelity, the trainee IPC counselors additionally were evaluated by examining item means from the modified IPC Competencies List (Wilkinson, 2015).

Qualitative Analysis

Content analysis was used to categorize the data from the modified Client Change Interview (see Table 3) for evaluating acceptability of IPC and BPS for the adolescents. The data were coded by a member from research group (P.P.) using conventional content analysis (see Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Each answer from the Client Change Interview was read carefully; key words or phrases that captured the adolescent perception of their treatment were recorded. The number of categories which developed through reading participants’ transcripts was kept limited. Preliminary codes were based on four first transcripts. The remaining transcripts were coded according to preliminary codes, and new codes were added if a response did not fit into an existing code. After all transcripts were coded, all data within each code were reviewed again, some data were combined, some data were not used (data which described adolescents’ perceptions specifically about research process were not used, as this was not relevant). The resulting categories were: feeling after the treatment, collaboration with the counselor, helpful aspects during the treatment, difficult aspects during the treatment and need of extra treatment after the treatment.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

At baseline, there were no significant differences between the IPC and BPS groups on depressive symptoms (BDI), psychological distress (YP-CORE), or global functioning (CGAS). Although not statistically significant, the sum score on ADRSc was higher among adolescents receiving IPC than among those receiving BPS (ADRSc sum score 17.94 vs. 13.95, p = .06). Comorbid anxiety disorders were significantly (X2(1, n = 55) = 4.23, p = .04) more common among adolescents randomized to IPC (39.4%) than BPS (13.6%) (Table 1). In addition, the proportion of adolescents with moderate MDD was higher among those randomized to IPC (30.3%) than BPS (13.6%) (Table 1).

Due to the significant group difference in anxiety disorders at baseline, repeated measures of variance used baseline anxiety disorder as a covariate (ANCOVA) to examine anxiety disorder’s effect on group differences and on change over time for all outcome measures. The analyses showed no significant effects for anxiety disorder as a covariate for any of the outcome measures; this suggests that anxiety disorders did not have an effect on changes over time or on differences between the treatment groups.

Effectiveness

The mean scores for the primary outcome measures (i.e., BDI, ADRSc) and the secondary outcome measure (i.e., YP-CORE) decreased and those of CGAS increased between treatment baseline and end of treatment, in both the IPC and BPS groups. At post-treatment, the effect sizes of the changes in IPC group were medium (range = 0.59–0.73) for all measures, whereas in BPS group all effect sizes were large (range = 0.83–1.53). Changes for both primary outcome measures were rather small in the IPC group between endpoint and 3-month follow-up (change in BDI mean = 0.78; change in ADRSc mean = − 0.14), while in the BPS group BDI scores remained stable (change = 0.49), but ADRSc scores increased somewhat (change = 3.18). Between 3-month and 6-month follow-ups, decreases for both primary outcome measures were again observed in both groups. For the secondary outcome measures, we observed a continuous, gradual decrease in YP-CORE scores and increase in CGAS scores in IPC group, while in the BPS group a leveling of effect was seen at 3-month follow-up and gains again achieved between 3-month and 6-month follow-up points. (See Table 2 for effect sizes at follow-up points and Fig. 3 for the pattern of change of primary outcome measures from baseline to 6-month follow-up in both groups, Online Resource 1 for all outcome measures comparing pre–post-treatment and 3- and 6-month follow-ups in both IPC and BPS groups.)

The difference between the effectiveness of IPC relative to BPS was examined with a group by time repeated-measures analysis of variance for the four assessment waves of outcome measures. The interaction of group x time was not statistically significant, suggesting that the changes in all outcome measures over time were not different between the IPC and BPS groups. The main effects of group were not significant for any of the outcome measures. However, main effects of time were significant for the BDI (F(3, 45) = 24.25, p = .000), ADRSc (F(3, 695) = 27.22, p = .000), CGAS (F(3,45) = 15.94, p = .000), and YP-CORE (F(3,45) = 30.87, p = .000), indicating that adolescents in both groups improved in all outcome measures over time.

At the end of treatment, 14 (48.3%) adolescents in IPC and 11 (52.4%) adolescents in BPS achieved treatment response (at least 50% symptom reduction) on the BDI (OR 1.18 (95% CI 0.38–3.63, p = .77)). Similarly, 15 (51.7%) adolescents in IPC and 15 adolescents (68.2%) in BPS achieved treatment response (at least 50% symptom reduction) on the ADRSc (OR 2.00 (95% CI 0.63–6.35, p = .24)). At the end of treatment, 15 (51.7%) adolescents in IPC and 14 (66.7%) in BPS achieved recovery on the BDI (sum score < 10) (OR 1.87 (95% CI 0.58–5.98, p = .29)). Twenty-one (72%) adolescents in IPC and 19 adolescents (86%) in BPS achieved recovery on the ADRSc (sum score < 15) (OR 2.41 (95% CI 0.56–10.44, p = .31)). Thus, many adolescents improved with treatment, but no significant group differences in treatment response or recovery were observed at the end of treatment.

At 3-month follow-up, 18 (62%) adolescents in IPC and 12 (60%) adolescents in BPS reached diagnostic remission for a depressive disorder, with no significant group differences (OR 1.09 (95% CI 0.34–3.51, p = .88)). Similarly, at 6-month follow-up, 23 (79%) adolescents in IPC and 15 (75%) in BPS reached diagnostic remission, with no significant group differences (OR 1.28 (95% CI 0.83–1.06, p = .72)).

Implementation Fidelity

IPC counselors’ adherence to clinical principles of IPC (Basic IPC competencies; Specific techniques; Overarching IPC-specific competencies) was rated between “not used” and “mastered relatively well” after the first supervision session (mean ranged from 1.25 to 3.26), but after the sixth session IPC counselors’ adherence was assessed to be between “mastered to a small amount” and “mastered well” (mean ranged from 2.00 to 3.82) in all areas. However, three IPC-specific techniques (communication analysis, decision analysis, and role-playing) had means that ranged from 2 to 2.91 after the sixth session. Those techniques were used infrequently during the treatments and thus were rated as not used for most of the sessions. Other IPC-specific techniques and all other items were rated above 2 after the first supervision session and above 3 after the sixth session, indicating IPC counselors’ ability to deliver IPC. (See list of assessed therapeutic components in Online Resource 2.)

Feasibility and Acceptability

Almost all (89%) adolescents completed the treatment; only 6 of the 55 adolescents dropped out during the IPC and BPS. Treatment completion rates were 88% (n = 29) in IPC and 91% (n = 20) in BPS. The adolescents who completed the treatment attended all planned sessions during the intervention and both follow-up sessions, even though some adolescents had moved to a different city (see Fig. 1). All IPC counselors attended all supervision sessions, except for seven sessions which were conducted by phone. Retention rates varied between the groups; four adolescents dropped out before the fourth session in the IPC group and two adolescents dropped out before the sixth session in the BPS group. These adolescents also did not attend the follow-up sessions. Reported reasons for dropping out from IPC were: moving to another part of the city, disagreement with a parent, child welfare issues, and feeling that a few sessions were enough. Reasons for dropping out from BPS were poor alliance with the BPS counselor and lack of motivation toward the treatment.

There were some differences across the groups in the adolescents’ perceptions of their treatments (Table 3). According to the content analysis, all adolescents who participated in the interview (n = 17) described feeling well after three months of IPC or BPS treatment, except for one adolescent in the IPC group. She felt the treatment was too short for her and there was not enough time to process things. Adolescents in both treatments gave high ratings for them. All adolescents rated their collaboration with the counselor as good except for one adolescent in the IPC group who expressed ambivalence about participating in the treatment.

Adolescents in both groups reported finding several factors helpful in the treatments. Across both treatment groups, perceived favorable factors included gaining a new perspective or starting to think about things (n = 5) and talking with somebody who understands (n = 8). In the IPC group, adolescents named several things which helped them to deal with their symptoms (e.g., “I got help on how to get new friends”, “I learned that everything is not my fault”) and helped them to act differently in difficult situations (e.g., “I don’t get angry so easily”, “I am able to think before acting”). They also named exercises/homework assignments as helpful (“A helpful homework assignment was to talk with my parents”, “Drawing a circular map of close people and the timeline were helpful for me”). Helpful aspects reported by adolescents in the BPS group were receiving practical advice (e.g., “I got advice not to do homework before going to sleep”; “I got advice about routines at evenings”) and ways of working with the adolescent problems (“I recognize my feelings better”, “I know what to do if I feel depressed”). Furthermore, adolescents in the BPS group described collaboration with the counselor and feeling understood (“The relationship became more and more trusting over time, and it was easier to talk” or “It was the first time I had the courage to ask and get help” or “I was asked about my feelings several times”).

Only three adolescents from both groups reported difficulties during treatment. One adolescent from each group reported difficulties related to attending the IPC and BPS (BPS: “Sometimes it was difficult to find time to meet the counselor”; IPC: “The treatment was too short”). One adolescent from each group reported difficulties regarding the content of the treatment (BPS: “The questions were difficult from time to time”; IPC: “Filling in questionnaires was not for me”). One adolescent from each group reported anxious feelings toward treatment situations (BPS: “It was difficult to concentrate, I felt difficult to be in treatment situations and I would not want to be there and it felt like it did not help, even if it really helped”; IPC: “Maybe certain things which we were talking about began to stress me, because I did things I do not like to talk about and they began to stick in my mind producing anxiety”).

The SWs’ evaluation of the implementation process was similar in the IPC and BPS groups (see Table 4). SWs in both groups were satisfied with the process. BPS counselors rated the measures’ usefulness and intention to use them in the future and the fluent flow of the treatment process more positively than IPC counselors. In contrast, counselors in the IPC group rated the treatment process and their intention to use the method in the future more positively than did BPS counselors.

Discussion

The present study addresses the critical issue of implementing evidence-based interventions in community settings. We implemented a brief evidence-based treatment, IPC, in a real-world treatment setting for 12–16-year-olds who self-referred or were referred for help from school-based services. IPC and the comparison treatment, BPS, were provided by SWs who received applied training in IPC or who were instructed to use their routine clinical methods enhanced by the systematic and repeated use of measures assessing depressive symptoms, general functioning, and psychological distress.

The results show that a brief, active treatment, either IPC or BPS, is effective in reducing symptoms of mild-to-moderate depression and increasing adolescents’ functioning and psychological well-being. This finding is consistent with results from previous studies conducted in school environments indicating that IPT-A and its adaptations (La Greca et al., 2016; Mufson et al., 2004b; Tang et al., 2009; Young et al., 2006a, b, 2010) are effective in treating adolescent depression or depressive symptoms. In the present study, the control treatment, BPS, targeted depressive symptoms. The SWs providing BPS were instructed to use their existing professional skills to help student cope with the symptoms of depression. BPS also included weekly monitoring of depressive symptoms, psychological distress, and functioning, whereas in some previous studies the control treatment resembled normal school counseling, including only pre- and post-assessments (e.g., Young et al., 2010, 2006a).

Effectiveness

Our findings that 52% and 72% of the adolescents in the IPC group and 67% and 86% in the BPS group achieved recovery at the end of treatment on the BDI and ADRS, respectively, compare well with the results of the school-based IPT-A study by Mufson et al. (2004b). In that study, 74% of the adolescents in 12-session IPT-A and 52% in TAU met the recovery criterion on the BDI at post-treatment. Given the shorter duration of IPC relative to IPT-A, our results suggest that even time-limited treatments can be effective as an early intervention for adolescent depression when delivered by an existing workforce (Mufson et al., 2015; Wilkinson et al., 2018).

In prior studies, the clinicians providing depression interventions in school settings have mostly been mental health professionals or researchers (Arora et al., 2019), whereas in our study both IPC and the BPS were provided by SWs from school-based services who besides school psychologist were not mental health professionals. This design allowed us to assess the effectiveness of both treatments in adolescents’ natural surroundings and to gain information on the feasibility of the interventions when delivered by multi-professional SWs as part of their routine work.

A significant finding is that treatment gains achieved following intervention delivered by professionals in a naturalistic setting were maintained over the six months post-treatment. This is consistent with the Weisz et al. (2013) meta-analysis, which showed that the benefits of longer evidence-based youth psychotherapies for a range of disorders have been maintained 6 months post-treatment in a number of trials. In the present trial, the symptom reductions at the six-month follow-up were not just maintained, but were even greater than those observed at the end of treatment. Most of the IPT-A studies have not presented follow-up analyses up to 6 months post-treatment (Mufson et al., 2004b, 2015; Tang et al., 2009; Young et al., 2006b). Overall, our follow-up results are especially encouraging and demonstrate that brief and active early interventions, such as IPC and structured psychosocial support, can maintain their effects post-treatment. Nonetheless, studies with larger samples and longer follow-ups are needed (e.g., Goodyer et al., 2017) to further support the use of these brief treatments.

In terms of the clinical significance of our findings, the observed medium pre–post-effect sizes for IPC (d = 0.59–0.73) are lower than the high pre–post-effect size of 1.23 reported in a meta-analysis of psychosocial treatments for youth depression (Michael & Crowley, 2002), but fall in the range of effect sizes (d = 0.30–2.27) they reported. In the present study, all participants had a diagnosed depressive disorder instead of only elevated depressive symptoms at baseline. Furthermore, our study was an effectiveness study conducted in a real-world school setting, and we assessed outcomes following SWs’ initial use of a new intervention after a short training period. These factors may help to explain the lower effect sizes obtained in this study.

The clinical outcomes were good in both treatment groups, with no statistically significant differences between IPC and BPS on measures of depressive symptoms, psychosocial functioning, and psychological distress at the end of treatment or at the 3- or 6-month follow-ups. This finding is consistent with the study by Kerfoot et al. (2004) who reported no differences between CBT and treatment as usual in treating adolescent depression in a community setting. Similarly, Goodyer et al. (2017) found no difference at 12-month follow-up in the level of depressive symptoms between cognitive behavioral therapy, short-term psychoanalytical therapy, and brief psychosocial intervention in specialized healthcare services. Meta-analyses by Weisz et al. (2006, 2017) report less benefit from psychotherapy in studies comparing evidence-based treatments with active comparison treatments than in studies with passive control conditions. Thus, using an active control condition may have had an impact on our findings of no difference in effectiveness between IPC and BPS.

In the present study, the analyses included the very first IPC treatments the SWs provided after their training. Hence, our results represent the effect of this treatment in the “practice phase.” Although the SWs were given systematic and regular method-specific supervision, it is likely that their competence in providing IPC would have increased after a greater number of supervised, completed cases (Owen, Wampold, Kopta, Rousmaniere, & Miller, 2016). Although the IPC counselors adherence to clinical principles of IPC were relatively good, except for the use of communication analysis, role-playing, and decision analysis, further experience might have had a more positive effect on the results. The relatively low use of the three IPC-specific techniques raises the possibility that IPC was not fully implemented. It may be that IPC counselors need more training in the IPC in order to use IPC techniques effectively. Similarly, in a previous study, the novelty of treatment-specific components influenced school counselors’ ability to implement a CBT-based program (Masia Warner, Brice, Esseling, Steward, Mufson, & Herzig, 2013). This might be a possible reason for not obtaining differences between the IPC and BPS.

Our decision to compare IPC with BPS, instead of more naturalistic “treatment as usual,” also may have affected the findings. Routine support and treatment in Finnish school-based services are not normally as intensive as BPS. Our findings suggest that a supportive intervention with targeted frequent sessions, which include repeated assessment of depressive symptoms, may be sufficient for reducing depression in youth. The feedback information may be one possible reason for adolescents’ improvements in both groups (see Bickman et al., 2011; Boswell et al., 2013; Hawkins, Lambert, Vermeersch, Slade & Tuttle, 2004). There is evidence that the feedback that adolescents themselves receive is important for their well-being (Hawkins, et al., 2004). We believe that the process of conducting symptom assessments and repeated monitoring of change may have been even more beneficial to SWs who worked without a single, defined treatment model (i.e., those providing BPS) than for those who used a structured treatment model such as IPC.

There was a trend for adolescents randomized to IPC to report more symptoms at baseline than adolescents randomized to BPS. Specifically, at baseline, the proportion of IPC adolescents with comorbid anxiety disorders was significantly higher and, although not statistically significantly, the proportion of IPC participants with moderate depression was three times higher in the IPC group than in the BPS group. In addition, the depression symptoms scores at baseline suggested more severe depressive symptoms in the IPC group versus the BPS group. Although these group differences were evident at baseline, they were not evident at treatment termination. In similar studies, those with more severe depression (Mufson et al., 2004b; Tang et al., 2009) or with a comorbid anxiety disorder (Young et al., 2006b) gained more from IPT-A in comparison with a control treatment. Thus, our findings suggest that IPC may be effective even if moderate depression or comorbid anxiety exists.

Feasibility, Acceptability, and Fidelity

In terms of treatment feasibility, both IPC and BPS were feasible for adolescents, the majority of whom (89%) were willing to attend all treatment and follow-up sessions. This attendance rate is comparable to previous studies on IPT-A conducted in school settings reporting attendance rates from 89 to 93% (Mufson et al., 2004b; Young et al., 2010). Reasons for dropping out from IPC were predominantly unrelated to treatment. In addition, SWs reported that treatment delivery was smooth in both groups, although this was even more evident in the BPS group. This difference may reflect the fact that IPC was a completely new and unfamiliar method to SWs and consequently was likely to require extra effort.

The acceptability of IPC and BPS was good for adolescents as all but one was satisfied with the treatment and reported feeling well three months after the treatment. Adolescents reported that the treatment helped in multiple ways, although five individuals felt that they still needed treatment. Therefore, six sessions may not be sufficient for everyone. In addition, the treatments seemed to be acceptable for SWs as well, as SWs in both groups felt that the treatment did help the adolescents. The IPC counselors valued the IPC method and credited their success to the supervision they received. Supervision seemed to have had a great impact on the entire IPC process. Prior studies of supervision during psychotherapy training indicate that supervision fosters counselors’ perceived self-efficacy in delivering therapy (e.g., Cashwell & Dooley, 2001), as well as enhancing counselors’ ability to attain key psychotherapeutic skills (Ögren & Jonsson, 2004). In addition, BPS counselors also highly valued the addition of repeated measures to their routine methods that they planned to implement again in future. This may reflect the importance of structure and feedback that repeated use of measures provided.

The fidelity of implementation was good, the IPC counselors’ adherence to clinical principles of IPC method improved during every session; only the novel, skills-based techniques used in IPC did not improve at the same level as the other competencies. This suggests that IPC implementation requires more repetition and familiarity with the IPC process. Future studies involving IPC treatments should ensure that IPC counselors more fully utilize the key IPC techniques by monitoring and addressing their use in supervision during the course of treatment. Nevertheless, the SWs’ adherence to using the IPC method was relatively good in this study, suggesting that IPC can be successfully delivered in school-based services.

Our results demonstrate that IPC can be learned and delivered by social workers and nurses who have little previous specific training in mental health issues or treatment of youth depression, as well as by psychologists who already have relevant training. The brief treatment seems to fit well in school-based services, as reflected by the good treatment retention, by the qualitative analysis of a subsample of adolescents, and by the structured questionnaire for the SWs about the feasibility and acceptability of IPC and BPS.

Strengths and Limitations

A clear strength of the study is that both treatments were delivered in a community setting—in a public school-based setting. Use of these services bears no cost to the families and is potentially less stigmatizing than clinic-based services. Furthermore, these services are easily accessible for adolescents and involve shorter delays to receiving treatment relative to those in specialized services. All adolescents attending public secondary schools had equal access to school-based services, and thus, the treatment sample was not skewed with respect to socioeconomic factors. Furthermore, the SWs trained in IPC were professionals working in these services and were able to deliver an effective, structured, and evidence-based intervention with minimal training and regular supervision, thereby expanding service provision for adolescents with potentially damaging mental health difficulties. These issues strengthen the external validity of the findings and suggest the generalizability of this effectiveness study to similar treatment settings.

Due to the relatively small study sample, caution is needed when interpreting the results. The sample may be biased toward inclusion of depressed youth who were motivated to engage in treatment. As the participants were 12–16-year-olds, the results may not generalize to older adolescents. Although dropping out from treatment was uncommon, adolescents’ refusal to participate in the study before the baseline assessment or SWs’ uncertainty about administering the screening procedures may have been issues. It is possible that youth with greater comorbidity or more problematic alcohol use refused to participate due to the assessment burden. Unfortunately, we were not able to definitively assess the numbers and rate of pre-assessment refusal. At present, Finnish adolescents may self-refer to school-based services without parental knowledge. Such privacy, which many adolescents wish to retain, was not possible in a clinical trial and could have influenced adolescents’ willingness to participate. Anecdotal comments from the SWs suggested that adolescents’ unwillingness to obtain parental consent was a frequent reason for not participating.

Methodological limitations to the study further include not masking the clinician assessments during treatment and follow-ups, which may have inflated the effects in the direction of the desired outcome. However, changes in these assessments were clearly in the same direction and of comparable magnitude as the self-report measures. A second methodological limitation is that clinicians conducting the K-SADS-5 interviews were not blinded to treatment condition. Third, the qualitative analyses included only a subgroup of adolescent participants. Thus, these results may not capture all adolescents’ perceptions of the treatments and associated changes. Fourth, instead of videotaped live sessions, IPC counselors’ adherence to the key IPC principles was evaluated by the supervisors based on the IPC counselors’ verbal reports during supervision sessions. Therefore, the possibility for biased or inaccurate reporting cannot be ruled out.

Implications

In conclusion, both IPC and BPS were found to be feasible, acceptable, and effective interventions for treating adolescents’ mild-to-moderate depression in the school setting. School-based health and welfare services seem to be an appropriate context to arrange short-term psychosocial treatments for adolescent depression. Short and focused interventions, which include systematic and repeated symptom monitoring, such as IPC and BPS, appear effective for decreasing adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Our feasibility and acceptability results indicate that such interventions can be delivered by professionals from school-based services and that they are acceptable to both intervention providers and adolescent clients. A practical implication is that our findings show promise for improving the early intervention of adolescent depression, as school-based services are ideal for reaching adolescents in their everyday lives and thus are of substantial public health importance. Factors predicting or moderating the effect of IPC need to be examined further, as IPC seemed to be effective even if the adolescents had moderate depression and comorbid anxiety disorders. As this study is the first randomized controlled trial of IPC in treating adolescent depression, further studies of IPC in the school context with active treatment comparisons and with larger samples are needed. Finally, our findings indicate that short and structured interventions, such as IPC and BPS, delivered by professionals from school-based services are effective in treating mild-to-moderate depression in school settings and yield results that can be maintained 6 months after the intervention.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Arora, P. G., Collins, T. A., Dart, E. H., Hernández, S., Fetterman, H., & Doll, B. (2019). Multi-tiered systems of support for school-based mental health: A systematic review of depression interventions. School Mental Health,11(2), 240–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09314-4.

Avenevoli, S., Swendsen, J., He, J.-P., Burstein, M., & Merikangas, K. (2015). Major depression in the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement: Prevalence, correlates, and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,54(1), 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.010.

Beck, A., & Beck, R. (1972). Screening depressed patients in family practice. A rapid technic. Postgraduate Medicine,52, 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.1972.11713319.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Carbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review,8(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5.

Beck, A. T., Ward, C., & Mendelson, M. (1961). Beck depression inventory (BDI). Archives of General Psychiatry,4(6), 561–571.

Bickman, L., Kelley, S. D., Breda, C., de Andrade, A. R., & Riemer, M. (2011). Effects of routine feedback to clinicians on mental health outcomes of youths: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatric Services,62(12), 1423–1429. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.002052011.

Bird, H. R., Andrews, H., Schwab-Stone, M., Goodman, S., Dulcan, M., Richters, J., . . . Gould, M. S. (1996). Global measures of impairment for epidemiologic and clinical use with children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 6(4), 295–307.

Birmaher, B., Ryan, N. D., Williamson, D. E., Brent, D. A., Kaufman, J., Dahl, R. E., et al. (1996). Childhood and adolescent depression: a review of the past 10 years. Part I. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,35(11), 1427–1439. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011.

Boswell, J. F., Kraus, D. R., Miller, S. D., & Lambert, M. J. (2013). Implementing routine outcome monitoring in clinical practice: Benefits, challenges, and solutions. Psychotherapy Research,25(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.817696.

Brière, F. N., Rohde, P., Seeley, J. R., Klein, D., Peter, M., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (2014). Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood. Comprehensive Psychiatry,55(3), 526–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.007.

Brooks, S. J., & Kutcher, S. (2001). Diagnosis and measurement of adolescent depression: A review of commonly utilized instruments. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology,11(4), 341–376. https://doi.org/10.1089/104454601317261546.

Cashwell, T. H., & Dooley, K. (2001). The impact of supervision on counselor self-efficacy. Clinical Supervisor Special Issue,20(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1300/J001v20n01_03.

Churchill, S. A., & Farrell, L. (2017). Alcohol and depression: Evidence from the 2014 health survey for England. Drug and Alcohol Dependence,180, 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.08.006.

Clarke, G., Hawkin, W., Murphy, M., Sheeber, L., Lewinsohn, P., & Seeley, J. (1995). Targeted prevention of unipolar depressive disorder in at-risk sample of high school adolescents: A randomized trial of group cognitive intervention. Journal of American Academy Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,34, 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199503000-00016.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Elliot, R. (2012). Brief change interview (1/12). Unpublished research instrument. Department of Psychology, University of Strathclyde.

Elliot, R. & Rodgers, B. (2008). Client change interview schedule: Follow-up version (v5). Retrieved June 10, 2019 from https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B4QhybeF75vsUzBtXy1tTTZTU3M/edit.

Flament, M. F., Cohen, D., Choquent, M., Jeammet, P., & Ledoux, S. (2001). Phenomenology, psychosocial correlates, and treatment seeking in major depression and dysthymia of adolescence. Journal of Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,40(9), 1070–1078. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200109000-00016.

Garber, J., & Weersing, V. R. (2010). Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in youth: Implications for treatment and prevention. Clinical Psychology: A Publication of the Division of Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association,17(4), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01221.x.

Gergov, V., Lahti, J., Marttunen, M., Lipsanen, J., Evans, C., Ranta, K., et al. (2017). The psychometric properties of the Finnish version of the Young Person’s Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (YP-CORE) questionnaire. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry,71, 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2016.1270352.

Girio-Herrera, E., Ehrilch, C. J., Danzi, B. A., & La Greca, A. M. (2019). Lessons learned about barriers to implementing school-based interventions for adolescents: Ideas for enhancing future research and clinical projects. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice,26(3), 466–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.11.004.

Goodyer, I. M., Reynolds, S., Barrett, B., Byford, S., Dubicka, B., Hill, J., et al. (2017). Cognitive behavioural therapy and short-term psychoanalytical psychotherapy versus a brief psychosocial intervention in adolescents with unipolar major depressive disorder (IMPACT): A multicentre, pragmatic, observer-blind, randomised controlled superiority trial. The Lancet Psychiatry,4(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30378-9.

Gore, F. M., Bloem, P. J., Patton, G. C., Ferguson, J., Joseph, V., Coffey, C., et al. (2011). Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: A systematic analysis. Lancet,377(9783), 2093–2102. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60512-6.

Gunlicks-Stoessel, M., Mufson, L., Jekal, A., & Turner, J. B. (2010). The impact of perceived interpersonal functioning on treatment for adolescent depression: IPT-A versus treatment as usual in school-based health clinics. Journal of Consultative Clinical Psychology,78, 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018935.

Haarasilta, L., Marttunen, M., Kaprio, J., & Aro, H. (2003). DSM-III-R major depressive episode and health care use among adolescents and young adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology,38, 366–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-003-0644-1.

Hankin, B. L., Abramson, L. Y., Moffitt, T. E., Silva, P. A., McGee, R., & Angell, K. E. (1998). Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,107(1), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.128.

Haravuori, H., Muinonen, E., Kanste, O., & Marttunen, M. (2017). (Mielenterveys- ja päihdetyön menetelmät opiskeluterveydenhuollossa: Opas arviointiin, hoitoon ja käytäntöihin.) Helsinki: THL. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-302-722-0 (in Finnish).

Hawkins, E. J., Lambert, M. J., Vermeersch, D. A., Slade, K. L., & Tuttle, K. C. (2004). The therapeutic effects of providing patient progress information to therapists and patients. Psychotherapy Research,14(3), 308–327. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptr/kph027.

Hawton, K., Saunders, K. E., & O’Connor, R. C. (2012). Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet,379(9834), 2373–2382. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60322-5.

Hietanen-Peltola, M., Vaara, S., & Laitinen, K. (2019a). Koulukuraattoripalvelujen yhdenvertaisuudessa on kehittämistarpeita—tuloksia perusopetuksen opiskeluhuollon seurannasta 2018. Tutkimuksesta tiiviisti 4/2019. Helsinki, THL. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-343-271-0 (in Finnish).

Hietanen-Peltola, M., Vaara, S., & Laitinen, K. (2019b) Koulupsykologipalvelujen yhdenvertaisuudessa on kehittämistarpeita—tuloksia perusopetuksen opiskeluhuollon seurannasta 2018. Tutkimuksesta tiiviisti 5/2019. Helsinki, THL. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-343-273-4 (in Finnish).

Horowitz, J. L., Garber, J., Ciesla, J. A., Young, J. F., & Mufson, L. (2007). Prevention of depressive symptoms in adolescents: A randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal prevention programs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,75(5), 693–706. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.75.5.693.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research,15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Jacobson, N. C., & Newman, M. G. (2017). Anxiety and depression as bidirectional risk factors for one another: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin,143(11), 1155–1200. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000111.

Jörg, F., Visser, E., Ormel, J., Reijneveld, S. A., Hartman, C. A., & Oldehinkel, A. J. (2016). Mental health care use in adolescents with and without mental disorders. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,25(5), 501–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0754-9.

Judd, F., Weissman, M., Davis, J., Hodgins, G., & Piterman, L. (2004). Interpersonal counselling in general practice. Australian Family Physician,33(5), 332–337.

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U., Flynn, C., Moreci, P., et al. (1997). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children—Present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,36(7), 980–988. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021.

Kerfoot, M., Harrington, R., Harrington, V., Rogers, J., & Verduyn, C. (2004). A step too far? Randomized trial of cognitive-behaviour therapy delivered by social workers to depressed adolescents. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,13(2), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-004-0362-6.

Klerman, G. L., Weissman, M. M., Rounsaville, B. J., & Chevron, E. (1984). Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Kontunen, J., Timonen, M., Muotka, J., & Liukkonen, T. (2016). Is interpersonal counselling (IPC) sufficient treatment for depression in primary care patients? A pilot study comparing IPC and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT). Journal of Affective Disorders,1, 189–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.032.

La Greca, A. M., Ehrenreich-May, J., Mufson, L., & Chan, S. (2016). Preventing adolescent social anxiety and depression and reducing peer victimization: Intervention development and open trial. Child & Youth Care Forum,45(6), 905–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9363-0.

Lauth, B., Arnkelsson, G. B., Magnússon, P., Skarphéðinsson, G. Á., Ferrari, P., & Pétursson, H. (2010). Validity of K-SADS-PL (Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children—Present and lifetime version) depression diagnoses in an adolescent clinical population. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry,64(6), 409–420. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039481003777484.

Law, R. (2011). Curriculum for practitioner training in Interpersonal Psychotherapy (Trainee). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: Trainee pack. [Improving Access to Psychological Therapies, Manual] Retrieved June 14, 2019 from https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160302160122/; http://www.iapt.nhs.uk/silo/files/curriculum-practitioner-training-in-interpersonal-psychotherapy-trainee-april-2011.pdf.

Leaf, P. J., Algeria, M., Cohen, P., Goodman, S. H., Horowitz, M. C., & Hoven, C. W. (1996). Mental health service in the community and schools: Results from the four-community MECA Study. Journal of American Academy Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,35, 889–897. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199607000-00014.

Liskola, J., Haravuori, H., Lindberg, N., Niemelä, S., Kettunen, K., Karlsson, L., et al. (2018). Utility of Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in screening problematic alcohol use among Finnish adolescents. Drug Alcohol Dependence,188, 266–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.015.

Markowitz, J. C., & Weissman, M. M. (2012). Interpersonal psychotherapy: Past, present and future. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy,19(2), 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1774.

Masia Warner, C., Brice, C., Esseling, P. G., Steward, C. E., Mufson, L., & Herzig, K. (2013). Consultants’ perceptions of school counselors’ ability to implement an empirically-based intervention for adolescent social anxiety disorder. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services,40, 541–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0498-0.

Menchetti, M., Bortolotti, B., Rucci, P., Scocco, P., Bombi, A., & Berardi, D. (2010). Depression in primary care: Interpersonal counseling vs. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. The DEPICS Study. A multicenter randomized controlled trial. The DEPICS Study. BMC Psychiatry,10, 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-10-97.

Menchetti, M., Rucci, P., Bortolotti, B., Bombi, A., Scocco, P., Kraemer, H., et al. (2014). Moderators of remission with interpersonal counselling or drug treatment in primary care patients with depression: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry,204(2), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.122663.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., et al. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Study-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,49(10), 980–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017.

Michael, K. D., & Crowley, S. L. (2002). How effective are treatments for child and adolescent depression? A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review,22(2), 247–269.

Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. (2018). Maternity and child welfare clinics, school and student health care and preventive oral health care: Grounds and application directives for decree (380/2009). Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriön julkaisuja 2009:20. Retrieved October 24, 2018 from http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-00-2942-5 (in Finnish).

Mufson, L. (2010). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents (IPT- A): Extending the reach from academic to community settings. Child and Adolescent Mental Health,12(2), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2009.00556.x.

Mufson, L., Pollack, D. K., Moreau, D., & Weissman, M. M. (2004a). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Mufson, L., Pollack, D. K., Wickramaratne, P., Nomura, Y., Olfson, M., & Weissman, M. M. (2004b). A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry,61, 577–584. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.577.

Mufson, L., Yanes-Lukin, P., & Anderson, G. (2015). A pilot study of Brief IPT—A delivered in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry,37(5), 481–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.04.013.

Myers, K., & Winters, N. C. (2002). Ten-year review of rating scales. II: Scales for internalizing disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,41(6), 634–659. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200206000-00004.

Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Upper secondary general school education [e-publication]. ISSN = 1799-165X. Helsinki: Statistics Finland [referred: 21.3.2018]. Access method: http://www.stat.fi/til/lop/index_en.html.

Ögren, M.-L., & Jonsson, C. O. (2004). Psychotherapeutic skill following group supervision according to supervisees and supervisors. The Clinical Supervisor,22(1), 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1300/j001v22n01_04.

Owen, J., Wampold, B. E., Kopta, M., Rousmaniere, T., & Miller, S. D. (2016). As good as it gets? Therapy outcomes of trainees over time. Journal of Counseling Psychology,63, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000112.

Persson, S., Hagquist, C., & Michelson, D. (2017). Young voices in mental health care: Exploring children’s and adolescents’ service experiences and preferences. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry,22(1), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104516656722.

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., et al. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy In Mental Health,38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7.

Pu, J., Zhou, X., Liu, L., Zhang, Y., Yang, L., Yuan, S., et al. (2017). Efficacy and acceptability of interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in adolescents: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Research,253, 226–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.023.