Abstract

As part of transformative consumer research, which attempts to achieve effective ways to improve people lives, this research focuses are on comprehending the issue of materialism, especially during the Covid-19 crisis. Few studies deal with materialism within the setting of developing nations, especially in a large populated consumer society like Egypt in the Arab region. For this purpose, this research adds to the prevailing literature on materialism through proposing and testing this research’s conceptual model to investigate whether or not compulsive buying behavior (CBB) has a mediating impact in the link between materialism values and consumers’ life satisfaction. The researcher adopted a quantitative research design and used a single-stage cluster sampling technique and mono method for data gathering through distributing a large-scale questionnaire instrument. The structural equation modelling (SEM) methodology was implemented. The findings confirmed that the model is specified and yields a fit. Results uncovered that amid Covid-19 pandemic, materialism and individual’s life satisfaction are insignificantly associated except for the happiness sub-component of materialism. Furthermore, the association between materialistic values and CBB is insignificant except for the happiness sub-component. There is an insignificant effect of CBB on individual’s life satisfaction. To add, CBB doesn’t mediate the relationship between materialism and individual’s life satisfaction. This entails that Egyptian consumers consider having possessions a source for happiness but not the core of success. They are engaged in compulsive consumption for happiness and this may not lead to life satisfaction. This implies that Covid-19 may have produced pressures on Egyptian consumers to seek happiness through buying behaviors. Consequently, marketers should have several interventions to the feelings of happiness and consumers’ general life satisfaction in their messages and social marketing campaigns.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

During the last two decades, some consumers’ behaviors have contributed to the aggravation of suffering and stress. However, other behaviors were directed to improving social well-being and reducing the negative effects of consumption. Across different nations, there is a prevalent concern for social well-being, environmental and moral consumption (Mick, 2006). There is a rationale of the transformative consumer research (TCR) to materialism studies, which emphasizes research that targets enhancing peoples’ wellbeing in societies. A continuous need for the TCR and for investigating the impediments for its potential growth and its integration with public policy making remains urgent (Davis et al., 2016). In the global consumer culture, people buy not only for the function of the product but also for the perceived value-meaning. Materialism is usually associated with consumers’ overspending and extreme debt levels. In addition, few researches emphasize how materialism influences such practices (Davis et al., 2016; Richins, 2011; Solomon, 2018). The Covid-19 crisis urged both global and local proactive actions from nations and firms (Charm et al., 2020). A TCR requires focusing on materialism (and its sub-components) to generate constructive insights and interpret materialism in developing nations with the attempt of reducing its harmful effects on consumers’ satisfaction about life and well-being (Davis et al., 2016).

Previous studies indicated that materialism is negatively associated with consumer’s high ethical principles. However, some individuals consume less and are concerned with non-material quality of life. Others are influenced by materialism, which drives them to acquire the goods offered by marketers (Massom & Sarker, 2017; Muncy & Eastman, 1998). Evaluating materialism remains a growing concern to marketers because it helps in understanding their attitude towards social responsibility. Some marketers have self-interests and foster materialism. In most situations, this may not be in the interest of society and may breed socially irresponsible consumer behavior (Muncy & Eastman, 1998). According to Mick (2006), the Association for Consumer Research (ACR) foregrounds researches that enhance people’s lives within several aspects of consumption effects. Yet, the vigorous consumers’ perceptions existing within materialism studies remain unexplained. This is further ramified with behavioral mediators. Although ample previous research studied materialism, empirical research lacks the exploration of the mediating influence of CBB in the route between materialistic values and general life satisfaction (Thyroff & Kilbourne, 2018). Thus, this study articulates how consumers’ materialistic values and views of their general life satisfaction could be shaped by CBB.

Some societies are more materialistic than others as they are economically better off. They may value the possessions of material products and perceive them as indicators of quality of life (Inglehart, 2000). Having more interpretations about consumers’ values and behaviors may help marketers design more effective marketing messages for their products (Khare, 2014) and direct people more towards moral consumption. In July 2018, Egypt had a population exceeding the 99,000,000 people and had an anticipated growth rate of 2.83% in the future (Import–Export Solutions, 2020). In the developing nations, especially in Egypt, consumers’ values are rapidly changing. Poor ethical behavior, unhealthy food consumption and high life dissatisfaction are some factors that shaped the excessive youth materialism. Although Egypt is undergoing an economic depression, compulsive buying habits remain a behavioral problem. Youth materialism is increasing in Egypt with its impacts on society, where parental influence took part in transmitting the materialistic values to younger consumers (Adib & EL-Bassiouny, 2012).

Previous studies on materialism focused on North America and the West (Unanue et al., 2014). Insufficient research was devoted to the Arab region, especially to a mass consumer society like Egypt. Nevertheless, the repercussion of Covid-19 pandemic altered the potential consumption behavior towards shopping and buying (Charm et al., 2020). Some previous studies such that of Inglehart (2000), demonstrated that the negative association between materialistic values and well-being might be the opposite or even with less effects in the developing nations. This requires further examination to add to theoretical perspectives and to the mediating relationships in materialism research (Unanue et al., 2014). The importance of this research originates from the fact that the different contexts or situational factors in some countries may provide more or less consumption opportunities. Hence, this shows different influences of materialism. According to Shrum et al. (2013), some cultures place varying emphasis on material products and have several outlets that induce conspicuous consumption. Thus, they could be more consumerist cultures than others.

The Covid-19 pandemic affected consumers’ behaviors worldwide and is bringing about a forthcoming change in their buying habits (Morsi, 2020). Unexpectedly, Egyptian consumers’ spending did not alter. However, it tends to be increasing for groceries and furniture. Consumers require more ownership of essentials such as home appliances and supplies rather than buying discretionary products such as clothes and house decoration products (Wahish, 2020). Egyptian consumers are subjected to economic pressures and financial challenges such as inflation and increased food prices, which affects their spending. Conversely, some consumers strive to adapt with a strict and minimized shopping list. Many wealthy households spend money without change and Egyptian youth experience a growth in a widespread range of consumer segments (Import–Export solutions, 2020). The state statistics agency reported that 32.5% of Egypt’s population lives under the poverty line. According to Egypt’s Voluntary National Review (2018), Egypt is adopting the 2030 vision that aims to develop responsible consumption and production, especially in food and energy consumption. Thus, Egypt is a consumer market that worth investigation with regards to materialistic values (happiness, success & centrality), compulsiveness and individuals’ general satisfaction about life.

Otero-López et al. (2011) indicated that materialistic values, individuals’ general satisfaction of life and addictive buying behavior links need further investigation. To add, the existence of some personal and behavioral factors that have mediation effects are worth exploration as they may change these interrelationships (Thyroff & Kilbourne, 2018). With the change in consumption activities, scarcity of resources, and the movement towards more sustainable societies, materialism remains to be a continuing and growing concern in marketing and consumer research. Recently, scholars devoted their efforts to the post-effects of the individuals’ materialistic values and called for such studies in various settings to reduce purchasing behaviors of unnecessary products during economic depression, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic (Charm et al., 2020).

Ruvio et al. (2014) mentioned that it is worthwhile to investigate the effects of materialism on consumer behavior during stressful times, where high materialistic people used buying as a stress-relief and a gate to manage their lives challenges. Studies on materialism are extensive. Nonetheless, the issue is complex and lacks conclusions regarding the influences of materialism in different nations (Massom & Sarker, 2017). The influences of consumers’ materialistic values and tendencies to perceive ownership of objects central to the goal of accomplishment remains questionable in different societies (Atanasova & Eckhardt, 2021). Therefore, the aim of this study is to comprehend the materialism in terms of values in a mass consumer society and interpret the conflicting findings about the link between materialistic values and life satisfaction. It clarifies which materialistic values affect the individuals’ general life satisfaction and CBB amid Covid-19 pandemic. Furthermore, it contributes to pre-existing knowledge about this link with the mediating presence of CBB, which received less attention in past studies despite the call to examine it. This research generates plausible insights for social marketers and public policy makers regarding these dimensions, their relationships and influence on citizens’ overall actions. Comprehending materialism is beneficial for both domestic and global consumer marketing research especially amid Covid-19 crisis.

2 Hypotheses development

This section goes over previous literature regarding the dimensions understudy to develop the proposed conceptual model and research hypotheses.

First, Belk (1985) viewed materialism as a personality characteristic. Richins and Dawson’s (1992) view, which is used in this study, regarded materialism as a belief and personal value in which people seek and find happiness through buying and possessing products rather than through developing relationships and consuming experiences. Consumers may have varying degrees of materialism contingent on the extent to which they consider owning things central to their goals accomplishment. The more they require, the more materialistic they are (Richins, 2017). Further, other scholars considered materialism an indicator of power (Schwartz, 1992), an intrinsic and/or extrinsic individual life goal (Kasser & Ryan, 1996), a belief about the goals sought by society (Inglehart, 2000) and a way to create meaning and reflect the consumer’s identity (Shrum et al., 2013). In addition, Atanasova and Eckhardt (2021) considered materialism a rationale for consumption, which is demonstrated in consuming experiences and products and/or having access to develop social imagery and accomplish happiness. However, their analysis of materialism does not take into account ownership centrality. This study considers materialism at the individual level with objects ownership.

Materialism has both desirable and adverse consequences on consumers’ lives (Burroughs & Rindfleisch, 2011). Some authors such as Faiza (2017) and Inglehart (2000) discussed materialism with a positive view, showing how it reflects the wealth of nations and has good impact on the individual’s life satisfaction when individuals are able to buy what they want. According to Richins and Dawson (1992), the augmented consumption behaviors, resulting from being materialistic, may increase the affluence and profits of firms and thus their abilities to improve, be more productive and innovative. Materialism values may help individuals achieve their short-run targets and fulfill their self-consciousness motives (Thyroff & Kilbourne, 2018). Some psychological illness such as anxiety, stress, low consumers’ generosity, and low life satisfaction accompany consumers’ materialism (Belk, 1985; Solomon, 2018). Dittmar’s study (2008) discussed that materialism aggravates immoral consumption and leads to dissatisfaction of one’s life. Moreover, maladaptive or compulsive consumption in societies may be among the signs of materialism (Ruvio et al., 2014). Pandelaere (2016) debated whether the link between materialistic values and well-being was mutual and proposed that there may be a route from illness to materialism which was more robust. Finally, materialistic behaviors have few or many influences on the social well-being. These influences may vary due to consumer’s underlying motives (Thyroff & Kilbourne, 2018).

The linkage between materialism and consumers’ life satisfaction has been investigated in previous studies. However, it is getting more complex as people continue to buy various products in some countries such as in developing countries (Baker et al., 2013; Pradhan et al., 2018; Thyroff & Kilbourne, 2018). Tsang et al. (2014) highlighted that utmost, materialistic values have been accompanied with reduced levels of consumers’ life satisfaction. This might be owed to several reasons. For example, those consumers with high materialistic values are less grateful due to unmet psychological needs. Frunzaru and Popa (2015) specified that materialism relates to life dissatisfaction and increases consumers’ desire for shopping. According to Muller et al. (2011), materialistic consumers have low life satisfaction, which makes them depressed. Therefore, highly materialistic people are both less satisfied and less happy about their general life than the low materialistic people.

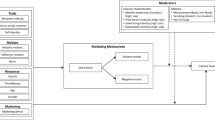

Sometimes consumers try to fill their emptiness by getting more things they do not need (Burroughs & Rindfleisch, 2011). With the improvement in technology, consumers’ purchasing actions are facilitated through existing physical and online stores. This made people more attentive to their material needs and buy some products compulsively (Cuandra and Kelvin, 2021). Materialistic consumers associate the value and individual’s well-being with buying and possessions. They believe that having possessions will improve their state, make them successful and happy (Dittmar, 2008; Richins & Dawson, 1992). Materialism has an effect (especially centrality) on CBB (Khare, 2014). On most occasions, compulsive buyers feel happy when they spend money (Faber & O’Guinn, 1992). However, a short-lived state of satisfaction and feelings of regret and guilt follow (Kellett & Totterdell, 2008; Solomon, 2018). Thus, this research seeks to examine the suggested conceptual model with its measurements and determine whether it is valid and consistent in the Arab context (Fig. 1).

Covid-19 pandemic had affected individuals’ consumption behaviors. To add, it caused several negative consequences such as economic pressures and health threats that become prominent across the globe. Nations urge their citizens to follow sustainable lifestyles (Charm et al., 2020; Morsi, 2020). Past studies supported the negative relationship between materialism and individuals’ life satisfaction in both developing and developed contexts (Baker et al., 2013; Belk, 1985). Nations have various environmental, socio-cultural and structural aspects which makes the effect of materialism different in each context. There is insufficient knowledge about materialism and its components, especially in the developing world (Massom & Sarker, 2017). The primacy of materialism studies conceptualized it as multidimensional and values-related construct. This construct has been prominent and valid in the mainstream studies with the use of three sub-components which are success, centrality and happiness. Materialistic consumers perceive possessions as the core of their lives, success and accomplishments. This reflects the centrality and success constituents respectively. The happiness constituent mirrors the consumers’ beliefs that buying and having possessions would make them happy (Richins & Dawson, 1992). However, dominant studies indicated that all of the materialistic values have negative relationships with the consumers’ general life satisfaction, keeping such negative relationships questionable and inadequately explained (Massom & Sarker, 2017). This guides to the proposition that there could be some personal or behavioral mediators that may provide a rationale for these associations (Otero-López et al., 2011; Thyroff & Kilbourne, 2018). Materialism studies proved the existence of a negative connection between materialism and individual’s general life satisfaction (Frunzaru and Popa, 2015; Mueller et al., 2011; Tsang et al., 2014). The following four hypotheses were developed as follows in reference to past studies:

-

H1: Materialism and individual’s life satisfaction are significantly and negatively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic

The first hypothesis is split into three sub hypotheses as follows:

-

H1a: Success and individual’s life satisfaction are significantly and negatively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic

-

H1b: Centrality and individual’s life satisfaction are significantly and negatively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic

-

H1c: Happiness and individual’s life satisfaction are significantly and negatively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic

Compulsive consumption is the process of repetitive and excessive type of shopping to overcome feelings of anxiety, boredom, depression and tension or inferiority (Belk, 1995). This addictive or habitual shopping is abnormal and individual spending manifests in uncontrollable desire to shop or buy material products or spend (Edwards, 1993; Islam et al., 2017; Khare, 2014; O’Guinn & Faber, 1989; Solomon, 2018; Xu, 2008). Materialistic consumers set their indicators of success in life with emphasis on achieving materialistic goals, this may progressively shift their behaviors towards compulsiveness (Dittmar, 2005). They center their lives on having possessions, this induces them to buy more (Massom & Sarker, 2017; Richins & Dawson, 1992; Ruvio et al., 2014). Furthermore, materialistic consumers find their happiness in buying and having more possessions which make them act compulsively (Pradhan et al., 2018; Ruvio et al., 2014). According to Wang et al. (2017), materialism and consumers’ happiness are positively linked. Compulsive buyers consider possessions as symbols of happiness (Khare, 2014). Dittmar (2005) emphasized that consumers’ materialistic values are crucial signals for CBB. Thus, previous studies found a positive link between materialism and CBB (Pradhan et al., 2018; Ruvio et al., 2014).

-

H2: The association between materialism and CBB is significant and positive amid Covid-19 pandemic

The second hypothesis is split into three sub hypotheses as follows:

-

H2a: Success and CBB are significantly and positively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic

-

H2b: Centrality and CBB are significantly and positively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic

-

H2c: Happiness and CBB are significantly and positively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic

Generally, various researches proved that reduced life satisfaction is associated with more tendencies towards compulsiveness in buying behavior and with high materialistic values (Dittmar, 2005). Pradhan et al. (2018) and Ruvio et al. (2014) emphasized the indirect negative influences of materialistic values and CBB on psychological well-being during stressful events and severe political and health conditions. They stated that materialism and CBB could make the bad conditions even worse. Materialistic consumers and compulsive buyers may have low self-esteem, which makes it difficult for them to adapt with stressful or difficult events. They initially supported the views of Belk (1985) and the conclusions of Richins and Dawson (1992) that shopping and consumption signify materialistic consumers’ behaviors in their attempt to adapt with problems in their societies. For example, coping with the pressing problems during the time of Covid-19 crisis. In general, compulsive buyers are happy when they purchase more and spend money (Faber & O’Guinn, 1992). However, satisfaction is short and limited due to feelings of guilt (Kellett & Totterdell, 2008). Ruvio et al. (2014) indicated that CBB is about an unplanned and unusual type of consumer shopping and spending behavior. In most situations, compulsive buyers find themselves in debt. This affects their financial well-being. Although consumers act in this compulsive way to ease their anxiety, their CBB lead to several negative consequences such as excessive debt, feelings of regret and short-lived satisfaction. Hence, the association between CBB and general life satisfaction could be negative (Edwards, 1993; Solomon, 2018).

-

H3: CBB and individual’s general life satisfaction are significantly and negatively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic

It has always been known that materialism and individuals’ life satisfaction are negatively associated. However Thyroff and Kilbourne (2018) proved that mediators such as self-enhancement and individual competitiveness altered this link to a positive one. Hence, there should be a better interpretation for this relationship and the inconsistencies in materialism studies, especially when some personal factors or values and behaviors such as CBB act as mediators (Baker et al., 2013). People with CBB have negative feelings, subject to motivational conflicts, which generate the chronic and psychological actions (Khare, 2014; Solomon, 2018). This leads to dissatisfaction about their lives in general. Therefore, compulsiveness in behavior may explain associations between individuals’ life satisfaction and materialism because possible dissatisfaction may be the root of CBB’s regret and guilt. The fourth hypothesis, hereby, represents partial mediation.

-

H4: CBB mediates the association between materialism and individual’s life satisfaction amid covid-19 pandemic

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

This study follows the positivism paradigm, which emphasizes a deductive approach to research. It is conclusive and descriptive in nature. A mono quantitative method with a cross-sectional strategy is used. Hypotheses were deduced and developed based on previous materialism studies, tested via the SPSS quantitative tools for analysis, AMOS and SEM test.

3.2 Measures

The researcher adopted the undermentioned three main measures:

3.2.1 Materialism (the personal value representation)

This present research follows Richins and Dawson (1992) perspective. The scale used to measure materialism includes eighteen statements that encompasses the three main personal values; centrality, success and happiness. They were scaled from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. Numbers in between indicate various levels of agreements. Centrality as a value denotes the extent to which consumers think that possessing products is the core of their lives. One of its measured attributes is that consumers believe that the things they own are all that crucial for them. Happiness refers to the extent to which consumers search for their happiness in buying and owning more things more than in being with other people. One of its measured attributes is that consumers are happy when they afford buying what they want. Success means that consumers consider possessing and buying products a sign for their success and social-image. One of its measured attributes is that consumers like to own things to impress other people.

3.2.2 Individual’s general Life satisfaction

There are principal constituents of judging one’s life as a good life, such as success in relationships, wealth and health. However, individuals assign different weights to such constituents and have different standards for success. Therefore, assessing the consumers’ global judgement of their lives rather than their satisfaction with different and specific domains is beneficial. Therefore, general life satisfaction is measured by adapting Diener et al. (1985) satisfaction with life scale (SWLS), which encompasses five statements measured on a seven-point Likert scale of agreement. This scale was extensively followed in past studies because it was mainly developed to evaluate satisfaction with a respondent’s entire life rather than with specific life domains. Thus, it measures the defining constituent of individuals’ well-being (Pavot & Diener, 1993).

3.2.3 Compulsive buying behavior (CBB)

The researcher adopted the CBB scale of Faber and O'Guinn (1992), which was measured on a five-point Likert statements/scale. 1 “never” indicates that such behavioral action is never taken by consumers and 5 “very often” indicates that such action is mostly taken by consumers. It is broadly used in past studies due to its popularity for being both valid and reliable in different contexts. Furthermore, according to Edwards (1993), it predicts abnormal behavior. This used scale underlines the main indicators of CBB as a uni-dimensional measure and includes statements that differentiate between compulsive consumers and other consumers. Hence, characterize compulsive versus non-compulsive buyers. It predicts the percentage of the population that is impacted by the CBB and shows the result of consumption. The scale here mirrors the features of CBB with the obsessive nature of consumers, lacking impulse control, distress at the thought of others' knowledge of the individual's spending habits, irrational use of credit and money in general, tension when not shopping and spending to feel better. For example, compulsive shoppers feel comfortable, more motivated to shop and spend on credit (Akram et al., 2018). This study doesn’t classify the types of CBB and measure their influence on the consumers’ life satisfaction. However, it investigates the impact of CBB as a uni-scale measure on life satisfaction. Therefore, there was no need for profiling this behavior by types (Edwards, 1993; Ridgeway et al., 2008).

3.3 Population and sampling

The population understudy comprises the Egyptian consumers. The researcher employed one-stage cluster sampling. It is one of the probability sampling techniques used when the population and the targeted sample size are large. The main population of this study is large and clusters function as a smaller representation of the whole Egyptian population. When clusters inclusively are studied, they encompass the population of Egypt (Saunders et al., 2019; Simkus, 2022). Thus, the researcher classified the large population of Egypt in to three clusters: upper, lower and central Egypt compromising the 27 governorates of Egypt (SIS, 2016). Then, individuals within each cluster were randomly selected to form the sample. Thus, the sample here reveals the study’s target population and reflects the various demographics of its members in an effort to prevent or reduce bias. Although cluster sampling is not as precise as stratified random sampling and simple random sampling, it is used as clusters naturally exist and can be geographically accessible in a convenient manner. In this research, there is no specific sampling frame and there is an infinite number of Egyptian consumers. Therefore, the sample size is calculated according to Saunders et al., (2019, p.302) equation of 95% confidence level, implying that the minimum sample size for an infinite population is 384 respondents.

3.4 Sample Description

The sample included 460 respondents. 51.3% were females and 48.7% males and the majority of them, 75.7%, work and 24.3% do not. Almost 49.8% of the respondents were single, 48.1% married, 1.7% divorced and 0.5% widowed. They were of multiple age groups ranges. 41.3% from 21 to 30 years (mainstream respondents), 37.2% of the mid-age range 31–40 years, followed by 11.1%, 9.3% and 1.1% of below 21 years, from 41 to 50 years and above 50 years respectively. The last cluster is the least number of respondents. They came from varying educational levels. 45.7% university graduates, 30.4% had a postgraduate or professional degree, 13.7% were having two years’ education after school, 7.4% completed their high school and 2.8% had IGCSE or equivalent international certificate. To add, respondents had different levels of average monthly income where 15.9% had the lowest income (less than EGP 3,000), 22.8% had income above EGP 3,000 but less than L.E. 6,000. 16.3%, 19.6% and 25.4% had income levels above 6,000 less than 9,000, above 9,000 less than 12,000, and more than EGP 12,000 respectively. The majority of the sample had an average monthly income of more than EGP 12,000, making 25.4%. Finally, respondents were from the three clusters of Egypt, where the majority of 43.5% were from Middle Egypt, 34.1% from lower Egypt and 22.4% were from upper Egypt. Descriptive statistics for the respondents’ personal profiles in Table 1.

3.5 Method of data collection

A large-scale survey method is used in this study. A questionnaire instrument was developed to include the three main dimensions, materialism, CBB and consumers’ life satisfaction and socio-demographics. Each statement was rated by respondents on measure of 5 points or 7 points Likert-scale nature. Greater scores mean higher level of constructs. Items specific to a given construct were separated from each other in the questionnaire to minimize consistency bias and reduce repetitiveness. Additionally, each measure in the materialism scale has included at least two reverse-coded items. CBB and individual’s life satisfaction scales have no reverse-coded items. The instrument with all its scales was translated into Arabic and then back-translated into the English version to ensure the quality and intended meaning for the phrased statements.

The questionnaire was a self-administered one, even as Covid-19 safety procedures and the lockdown was enforced Egypt. The researcher kept social distance in interactions and distributed the questionnaire in a safe and clean envelope with a small sanitizer to participants. A pilot study that included 60 respondents was conducted. Both reliability and validity were confirmed and the pilot sample was integrated into the overall sample understudy. The survey instrument pilot was achieved by administering the questionnaire to a small sample of 60 respondents from the three clusters of Egypt. Furthermore, three academic experts in the marketing and consumer behavior fields revised the questionnaire and deemed it to be valid. The usefulness of the instrument as an evaluation tool for materialism, CBB and life satisfaction was evaluated, indicating the time required to complete the survey and ensuring respondents anonymity and confidentiality. To recognize the autonomy of respondents, the researcher provided participants a concise introduction about the purpose of the study and emphasized how it supports enhancing the potential of consumption behavior in Egypt. The researcher presented a consent form to participants for agreement and approval to provide responses. It was communicated that participants are taking part in the study through voluntarily contribution and data collected is only for this research purposes. Participants have the right to ask questions for clarification. They can withdraw themselves or remove any information that they have provided in advance of the survey completion, without being disadvantaged in any way.

4 Data analysis

Data was gathered over three months (November, December 2021 to January 2022) during the Covid-19 Pandemic at various periods, reducing bias and sampling error. Covid-19 emerged in Egypt during March 2020 and continues to date. The government and the developed higher committee by the prime minister, to fight Covid-19 virus, have executed a lockdown all over Egypt’s governorates and took firm social distancing procedures to limit the effects of the pandemic. The Ministry of Health and population and government faced some difficulties such as the economic slump and limited capacity of covid-19 tests that led to indecisive count of infected cases. To surpass the downturn in economy due to the crisis, the government has been flexible in managing the lockdown and progressively alleviated the restrictions. The Lockdown restrictions did not continue for a long time and were eased by early November 2020 (Assaad et al., 2022; Beschel, 2021). Data was taken from different clusters in Egypt to ensure a broad and varied mix of respondents. The questionnaire was distributed in both the Arabic and English. After distributing 800 questionnaires, 460 questionnaires were completed and returned, representing 57.5% response rate. That is satisfactory and acceptable in social science research (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016).

This section provides the outcomes of AMOS – Version 25. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) is applied using the covariance method. Then, SEM is adopted to examine the research hypotheses. As a preliminary step, a descriptive analysis is displayed for the respondents’ profile and the research variables.

4.1 Descriptive Analysis for research variables

Table 2 represents research variables included in the 5-points Likert Scale. It can be deduced that the mean values of the research variables; Success Scale, Centrality Scale, Happiness Scale, and CBB Scale are 3.0413, 2.8326, 3.2326, and 2.7000 respectively. The responses observed are all within the midpoint and respondents are neutral regarding the research variables, which could mean that respondents are not satisfied with the levels of agreements for these dimensions.

Table 3 shows the descriptive analysis results of the research variables with 7-points Likert Scale, where Life Satisfaction was represented using the 7-points Likert scale. It was observed that the mean of consumers’ Life Satisfaction is 5.2022, referring to the existence of responses in the ‘agree’ zone.

4.2 Reliability test

Testing the reliability is a prerequisite to the consistency of the instrument and scales used to measure the specified research variables. Reliability determines the scale’s ability to produce consistent results during replication. Cronbach’s alpha is the most popular method to test the reliability of scales. According to Sekaran and Bougie (2016), if the value of Cronbach’s alpha is 0.7 or above, then the scale is reliable. Table 4 presents the values of Cronbach’s Alpha for the scales which are ranging between 0.759 and 0.970, which convey highly reliable scales.

4.3 Measurement Model

There is a model-fit criteria, which prove the model fit. The CFA was computed. Table 5 displays the scores of the SEM and the model fit indices with their cut-off values/or acceptable ranges for the fit. It was found that the minimum discrepancy or chi-square divided by the degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) was 1.42. The probability of getting larger discrepancy as the one that occurred with the present sample (p-value) is 0.00. After adjustment, it becomes 0.08. The Goodness-of-fit outcome indicates the overall acceptability of the analyzed structural model. It includes the goodness of fit (GFI) denoted as 0.92 and adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) denoted as 0.91. This evaluates how fit the model is against the number of estimate coefficients or the degrees of freedom needed to achieve that level of fit. Findings show that values of GFI and the AGFI of the modified model are both greater than 0.90, close to 1. Therefore, to improve these values, covariance should be considered among the latent variables (materialism, success, centrality, happiness, CBB and life satisfaction).

The CR can be interpreted as the t-value, where a value of 1.96 is translated into a 0.05 significance level (P-value). Hence, any value of critical ratio above 1.96 or p-value less than or equal to 0.05 is considered significant for the model (Byrne, 2010; Hair et al., 2010). The Bentler-Bonett normed fit index (NFI) was 0.95 and the Tucker-Lewis index or Bentler-Bonett non-normed fit index (TLI) was 0.98, which assess the incremental fit of the model compared to a null model. The comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.07, less than 0.10. This indicates a good model fit. In addition, the root mean square residual (RMR) was 0.03, which demonstrates how sample variances and covariances differ from their estimates obtained assuming the model is sound. The root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.03, an informative criterion in covariance structure modelling. It measures the amount of error present when attempting to estimate the population. Its value is between 0.05 and 0.08, a close fit. The chi-square with a significance level 0.92 is greater than 0.90. Therefore, the Ho is accepted. There is no difference between the Σ and S. In other words, the difference between the actual and the hypothesized data is equal to zero. This ascertains a model fit.

The CR is greater than 1.96 only for the links between materialism and its components. However, the critical ratio is below the 1.96 for the link between materialism and life satisfaction, between materialism and CBB and between CBB and life satisfaction. The model is specified and yields a fit. However, the existing relationships were not significant; they may not be true. Figure 2 shows the CFA had been applied, where the factor loadings are shown on arrows implying good factor loadings for the CFA.

Accordingly, it assessed the extent these dimensions and their measurement scales are valid. Table 6 shows that all factor loadings (FL). FL is the size of the loadings of items on their corresponding variable, which is at least 0.40 to be deemed valid.

Table 7 shows the discriminant validity of the research variables, where all square roots of AVE values are greater than the correlations between the corresponding construct and other constructs. This means that the research variables have adequate discriminant validity.

4.4 Hypotheses testing results

4.4.1 Testing the influence of materialism on life Satisfaction

Table 8 shows the SEM analysis of the impact of the materialism; success, centrality, and happiness scales on life satisfaction. It could be observed that there is an insignificant effect of success scale on life satisfaction as the corresponding P-value is greater than 0.05 (P-value = 0.70). Therefore, the first sub hypothesis of the first hypothesis “H1a: Success and individual’s life satisfaction are significantly and negatively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic” is not supported. Similarly, it was observed that there is an insignificant effect of centrality scale on life satisfaction as the corresponding P-value is greater than 0.05 (P-value = 0.49). Therefore, the second sub hypothesis of the first hypothesis “H1b: Centrality and individual’s life satisfaction are significantly and negatively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic” is not supported. However, it was found that there is a negative significant impact of happiness scale on life satisfaction as the corresponding P-value is less than 0.05 and the estimate value is less than zero (P-value = 0.01, Estimate = -0.15 and standardized estimate = -0.14). Therefore, the third sub hypothesis of the first hypothesis “H1c: Happiness and individual’s life satisfaction are significantly and negatively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic” is supported. The results above reveals that the first hypothesis “H1: Materialism and individual’s life satisfaction are significantly and negatively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic” is partially supported as the first and second sub-hypotheses were not supported but the third sub-hypothesis was supported.

4.4.2 Testing the influence of materialism on CBB

Table 8 shows the SEM analysis of the impact of materialism (Success, centrality and happiness scales) on CBB. It could be observed that there is an insignificant effect of success scale on CBB as the corresponding P-value is greater than 0.05 (P-value = 0.10). Therefore, the first sub hypothesis of the second hypothesis “H2a: Success and CBB are significantly and positively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic” is not supported. Similarly, it was observed that there is an insignificant effect of centrality scale on CBB as the corresponding P-value is greater than 0.05 (P-value = 0.33). Therefore, the second sub hypothesis of the second hypothesis “H2b: Centrality and CBB are significantly and positively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic” is not supported. However, it was found that there is a positive significant impact of happiness scale on CBB as the corresponding P-value is less than 0.05 and the estimate value is less than zero (P-value = 0.01, Estimate = -0.11 and standardized estimate = 0.14). Therefore, the third sub hypothesis of the second hypothesis “H2c: Happiness and CBB are significantly and positively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic” is supported. The above results revealed that the second hypothesis “H2: The association between materialism and CBB is significant and positive amid Covid-19 pandemic” is partially supported as the first and second sub-hypotheses were not supported but the third sub-hypothesis was supported.

4.4.3 Testing the effect of CBB on Life Satisfaction

Table 8 shows the SEM analysis CBB’s impact on life satisfaction. It could be observed that there is an insignificant impact of CBB on Life Satisfaction as the P-value is greater than 0.05 (P-value = 0.66). Therefore, the third hypothesis “H3: CBB and individual’s general life satisfaction are significantly and negatively associated amid Covid-19 pandemic” is not supported.

4.4.4 Testing the Mediation Role of CBB

Table 8 shows the SEM analysis of the mediation role of CBB in the link between materialism and life satisfaction. It could be observed that CBB has an insignificant effect on life satisfaction. Therefore, CBB does not mediate the relationship between Materialism and Life Satisfaction. To add, all indirect effects are equal zero, which means that there is no indirect effect; no mediation effect of compulsive buying behavior on the relationship between materialism and life satisfaction.

The model fit indices; CMIN/DF = 1.42, GFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.99, AGFI = 0.91, and RMSEA = 0.03 are all within their acceptable levels. The SEM model conducted for the mediation role of CBB between materialism and life satisfaction is illustrated in Fig. 3. Therefore, the fourth hypothesis “H4: CBB mediates the association between materialism and individual’s life satisfaction amid Covid-19 pandemic” is not supported.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

Unlike conclusions of predominant research on materialism such as that of Tsang et al. (2014), which underlined the significant and negative link between materialistic values and consumers’ general life satisfaction, this study proved that such link is insignificant except for the happiness sub-component. This adds and acts as support to the scientific debate of some studies such as of Thyroff and Kilbourne (2018) and Unanue et al. (2014), which suggested that conflicting results appear because of different contexts, specific psychological and behavioral aspects.

Contrasting the mainstream studies which emphasized the positive and significant association between materialism and CBB such as that of Dittmar (2005) and Ruvio et al. (2014), this research indicated that such link is insignificant except for the happiness sub-component. This implies that consumers’ materialistic values may not always guide them to act in an addictive way. To add, this study proved that there is an insignificant and negative link between CBB and life satisfaction. According to this research, when consumers centralize their goals on possessions or envision them as signs of success, this might not influence general life satisfaction or incite them to buy more items as indicated by Dittmar (2005). This could be valuable insight for marketers in a developing and mass consumer society like Egypt, in the Arab world. Leading to a conclusion that possessions may not be a sufficient condition for life satisfaction and could not be a signal of compulsiveness. Hence, stressing the centrality and success values in marketing messages might not alter consumers’ behaviors and may not make consumers satisfied about life. Therefore, the view of Richins and Dawson (1992) that materialistic values reflect common aspects in consumers in various cultures is further explained in this study. One or all of the materialistic values may differ across different countries, which makes materialism better interpreted when used as a value-oriented dimension among consumers.

This research indicated that the CBB has no mediating role in the linkage between materialism and consumers’ general life satisfaction. Therefore, materialistic values of Egyptian consumers exist and are related to emotional motives like happiness. If researchers include some socio-demographic variables, personality cues and/or rational motives as moderators to the proposed model, this may add some insights to interpreting the CBB and materialism matters. The assessment of consumers’ ethical consumption behavior and its association with materialism would enrich pre-existing literature about the implementation of the nation’s sustainability plans. Appraising the differences between CBB and the immediate and prolonged effects of impulsive buying behavior in relation to the outcomes of materialism would yield more insights to consumption behavior.

Although Egypt has undergone several economic problems and struggled to improve individuals’ lives, when consumers seek their happiness in possessions and buying more, they are not satisfied. This implies that consumers may not be satisfied with their basic needs and/or want to feel secured by having possessions. Some biogenic needs, psychological motives and nation-related factors such as economic conditions may affect the association under study. Egyptian consumers may be financially constrained and their materialistic views could be directly reflected in their buying behaviors but not necessarily for life satisfaction. This may indicate that Covid-19 time was a stressful time period that affected consumers’ buying behaviors. This study provided critical reflection on the individuals’ materialism states in a large populated Arab societal environment, Egypt. Consumers who are thoughtful of the meaning and purpose of life have lower life satisfaction than those who are not preoccupied by such thoughts. Egyptian consumers do not center their lives on buying more products. It is just the case that people are happier when they are able to buy. To further support this argument, Vinson and Ericson (2012) previously reported that in a wider societal framework, social marketers and policy makers should pay more attention to the impressions of happiness and their interconnections with consumers’ life satisfaction to increase both citizens’ contentment and worthiness of life. Consequently, marketers should use social messages to show how the outcomes of materialism may influence consumers’ lives. Then, they may positively induce people to purchasing behaviors that would both develop happiness and improve their social well-being.

6 Limitations and venues for future research

A cross sectional research does not show the change in behavior of consumers towards buying or the change captured in their materialistic values. In addition, cluster sampling is not precise as a stratified random sample for generalizing results. Future studies may embody cultural and subcultural (ex: residential areas) dissimilarities across the various governorates in Egypt. They may adopt qualitative approaches to explore the relationship between materialism and life satisfaction and better interpret consumers’ motives for compulsive behavior. Although this study was conducted during a time of crisis during the Covid-19 pandemic, stress was not used as one of the dimensions. Therefore, future studies may address the effect of materialism on the overall dimension of stress and its types.

This study’s outcomes align with the conclusions of previous studies that consider the effects of materialism as negative on the consumers’ well-being, especially with the component of happiness as the highest one for consumers’ materialistic values in Egypt. Potential studies should include different cultures or contexts to interpret the positive impacts of materialism on consumers’ well-being. In addition, further studies should include qualitative studies that uncover the in-depth motives underlying materialism and individuals’ purchasing decisions. Unlike Pandelaere’s research (2016), this study did not discuss the differences between material and experiential consumption. Rather, it focused only on the material one in general. This distinction might be helpful for uncovering the materialism effects on citizens’ behaviors especially in consumer societies such as Egypt.

In further studies, researchers should evaluate the impact of materialism outcomes on both consumers’ negative and positive emotions. This will help marketers determine differences or inconsistencies in consumers’ feelings towards having possessions or acting compulsively in their buying. Further analysis about what type of purchases would make people happy and satisfied on the long run may be useful because this could be the marketers’ route to persuade consumers about sustainable consumption. Further studies should explain why some people are compulsive buyers and place more emphasis on personality and other psychological motives or varying environmental factors across countries. Examining the motives of CBB supports marketers in designing effective and ethical messages to reduce compulsiveness, especially during stressful economic times. Potential research opportunities may relate the CBB to the consumers’ personalities in the Arab world, especially in developing nations during the post-covid period.

References

Adib, H., & El-Bassiouny, N. (2012). Materialism in Young Consumers: An Investigation of Family Communication Patterns and Parental Mediation Practices in Egypt. Journal of Islamic Marketing., 3(3), 255–282. https://doi.org/10.1108/17590831211259745

Akram, U., Hui, P., Kaleem Khan, M., Tanveer, Y., Mehmood, K., & Ahmad, W. (2018). How website quality affects online impulse buying: Moderating effects of sales promotion and credit card use. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 30(1), 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-04-2017-0073

Assaad, R., Krafft, C., Marouani, M. A., Kennedy, S., Cheung, R., & Wahby, S. (2022). Egypt covid-19 country case study. International Labour Organization & Economic Research Forum Report, 1–64. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---africa/---ro-abidjan/---sro-cairo/documents/publication/wcms_838226.pdf

Atanasova, A., & Eckhardt, G. M. (2021). The Broadening Boundaries of Materialism. Marketing Theory, 21(4), 481–500, Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.1177/14705931211019077.

Baker, A. M., Moschis, G. P., Ong, F. S., & Pattanapanyasat, R. (2013). Materialism and life satisfaction: The role of stress and religiosity. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 47(3), 548–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12013

Belk, R. W. (1985). Materialism: Trait Aspects of Living in the Material World. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1086/208515

Belk, R. W. (1995). Hyper-reality and globalization: Culture in the age of Ronald McDonald. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 8(3/4), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J046v08n03_03

Beschel, R. (2021). Policy and institutional responses to covid-19 in the Middle East and North Africa: Egypt. The Brookings Doha Center (BDC). January, 1–23. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/MENA-Covid-19-Survey-Egypt-January-28-2021-1.pdf

Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, A. (2011). What welfare? On the definition and domain of consumer research and the foundational role of materialism. In D. G. Mick, S. Pettigrew, C. Pechmann, and J. L. Ozanne (Eds.), Transformative consumer research for personal and collective well-being (pp. 249–266). New York: Routledge

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, applications, and Programming. Multivariate Application Series, 2nd edition, Routledge, Taylor& Francis Group, USA.

Charm, T., Dhar, R., Haas, S., Liu, J., Novemsky, N., & Teichner, W. (2020). Understanding and shaping consumer behavior in the next normal. Mckinsey &Company and Yale Center for Consumer Rights, July, Marketing &Sales Practice, Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/understanding-and-shaping-consumer-behavior-in-the-next-normal

Cuandra, F., & Kelvin, K. (2021). Analysis of influence of materialism on impulsive buying and compulsive buying with credit card use as mediation variable. Jurnal Manajemen, 13(1), 7–16. journal.feb.unmul.ac.id/index.php/JURNALMANAJEMEN

Davis, B., Ozanne, J. L., & Hill, R. P. (2016). The Transformative Consumer Research Movement. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, Fall, 35(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.16.063

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Dittmar, H. (2005). A New Look At Compulsive Buying: Self-discrepancies and Materialistic Values. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(6), 832–859. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2005.24.6.832

Dittmar, H. (2008). Consumer culture, identity, and well-being: The search for the “good life” and the “body perfect.” Psychology Press.

Edwards, E. A. (1993). Development of A New Scale For Measuring Compulsive Buying Behavior. Financial Counselling and Planning, 4, 67–85.

Egypt’s Voluntary National Review (2018). 2030 Vision of Egypt. Arab republic of Egypt: The Ministry of Planning, Monitoring and Administrative Reform. The United Nations Resident Coordinator Office and the United Nations Development Programme.

Faber, R. J., & O’Guinn, T. C. (1992). A clinical screener for compulsive buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1086/209315

Faiza, A. (2017). An Investigation of Materialism and Life Satisfaction. Journal of Educational, Health and Community Psychology, 6(3), 10–24.

Frunzaro, V., & Popa, E. M. (2015). Materialistic Values, shopping, And Life Satisfaction in Romania. The Romanian Journal of Sociology, new series, year XXVI, no. 3–4, 299–313, Bucharest, Romania: Quality of life and consumption in Romania.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th edition, Upper saddle River, New Jersey, Prentice Hall.

Import-Export Solutions (2020). Export Enterprises SA, Société Générale (2020), September, Egypt: The Market. Retrieved from: https://import-export.societegenerale.fr/en/country/egypt/market-consumer

Inglehart, R. (2000). Globalization and postmodern values. Washington Quarterly, 23, 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1162/016366000560665

Islam, T., Wei, J., Sheikh, Z., Hameed, Z., & Azam, R. I. (2017). Determinants of compulsive buying behavior among young adults: The mediating role of materialism. Journal of Adolescence, 61, 117–130, July. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.10.004

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(3), 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296223006

Kellett, S., & Totterdell, P. (2008). Compulsive Buying: A Field of Study of Mood Variability During Acquisition Episodes. The Cognitive Behavior Therapist, 1(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X08000056

Khare, A. (2014). Money Attitudes, Materialism, and Compulsiveness: Scale Development and validation. Journal of Global Marketing, 27(1), 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2013.850140

Massom, M. R., & Sarker, Md. M. (2017). Rising materialism in the developing economy: Assessing materialistic value orientation in contemporary Bangladesh. Cogent Business & Management, 4(1), 1345049. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2017.1345049

Mick, D. G. (2006). Presidential Address: Meaning and mattering through transformative consumer research in Cornelia Pechmann and Linda L. Price, eds. Advances in consumer research, 33, 1–4. U.S.: Association for Consumer Research.

Morsi, A. (2020). Consumers adapting to the coronavirus. Al-Ahram Weekly online report, April.https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/50/1201/368269/AlAhramWeekly/Egypt/Consumers-adapting-to-the-coronavirus.aspx. Accessed August 14th, 2021.

Mueller, A., Mitchell, J. E., Peterson, L. A., Faber, R. J., Steffen, K. J., & Crosby, R. D. (2011). Depression, materialism, and excessive internet use in relation to compulsive buying. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52, 420–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.09.001

Muncy, J. A., & Eastman, J. K. (1998). Materialism and Consumer Ethics: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(2), 137–145, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Netherlands.

O’Guinn, T. C., & Faber, R. J. (1989). Compulsive buying: A phenomenological exploration. Journal of Consumer Research, September, 16(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1086/209204

Otero-López, J. M., Pol, E. V., Bolaño, C. C., & Mariño, M. J. S. (2011). Materialism, Life satisfaction and Addictive Buying: Examining the Causal Relationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(6), 772–776. Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.027

Pandelaere, M. (2016). Materialism and Well-being: The Role of Consumption. Current Opinion in Psychology, August, 10, 33–38, Elsevier Ltd, Science Direct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.10.027

Pavot, W. G., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. In E. Diener (ed.), Assessing Well-Being: The Collected Works of Ed Diener (2009). Social Indicators Research Series, 39, 101–117, Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_5

Pradhan, D., Israel, D., & Jena, A. K. (2018). Materialism and compulsive buying behavior: The role of consumer credit use and impulse buying. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Patrington, 30(5), 1239–1258, Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-08-2017-0164

Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A Consumer Values Orientation For Materialism And Its Measurement: Scale Development And Validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1086/209304

Richins, M. L. (2011). Materialism, Transformation Expectations, and Spending: Implications for Credit Use American marketing Association. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, Fall, 30(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.2307/23209270

Richins, M. L. (2017). Materialism Pathways: The Processes that Create and Perpetuate Materialism. Journal of Consumer Psychology, August, 27(4), 480–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2017.07.006

Ridgeway, N. M., Kukar-Kinney, M., & Monroe, K. B. (2008). An Expanded Conceptualization And A New Measure Of Compulsive Buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(4), 622–639. https://doi.org/10.1086/591108

Ruvio, A., Somer, E., & Rindfeisch, A. (2014). When Bad Gets Worse: The Amplifying Effect of Materialism on Traumatic Stress and Maladaptive Consumption. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(1), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-013-0345-6

Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research Methods For Business Students (8th ed.). United Kingdom.

Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach (7th ed.). Wiley.

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2010). Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review. The Journal of Education Research, 99(6), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60281-6

Shrum, L. J., Wong, N., Arif, F., Chugani, S. K., Gunz, A., Lowrey, T. M., Nairn, A., Pandelaere, M., Ross, S. M., Ruvio, A., Scott, K., & Sundie, J. (2013). Reconceptualizing Materialism as Identity Goal Pursuits: Functions, Processes, and Consequences. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1179–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.010

Simkus, J. (2022, Jan 03). Cluster Sampling: Definition, Method and Examples. Simply Psychology. Retrieved From: www.simplypsychology.org/cluster-sampling.html

Solomon, M. J. (2018). Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having and Being. 12th edition, Pearson Education Limited, England.

State Information Service (SIS). (2016). Your Gateway to Egypt. Retrieved from: https://www.sis.gov.eg/section/210/16?lang=en-us.

Tsang, J.-A., Carpenter, T. P., Roberts, J. A., Frisch, M. B., & Carlisle, R. D. (2014). Why are materialists less happy? The role of gratitude and need satisfaction in the relationship between materialism and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, Elsevier Ltd., 64, 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.02.009

Thyroff, A., & Kilbourne, W. E. (2018). Self-enhancement and individual competitiveness as mediators in the materialism/consumer satisfaction relationship. Journal of Business Research, Elsevier Inc., November, 92, 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.023

Unanue, W., Dittmar, H., Vignoles, V. L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2014). Materialism and Well-being in the UK and Chile: Basic Need Satisfaction and Basic Need Frustration as Underlying Psychological Processes. European Journal of Personality, April, 28, 569–585, Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1954

Vinson, T., & Ericson, M. (2012). Life Satisfaction and Happiness. Richmond. Jesuit social Services. www.jss.org.au. pp. 1–76.

Wahish, N. (2020). Egypt: Consumer Trends in Lockdown. Al-Ahram Weekly online report, May. https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/50/1202/368726/AlAhramWeekly/Economy/Egypt-Consumer-trends-in-lockdown.aspx. Accessed August 14th, 2021

Wang, R., Liu, H., Jiang, J., & Song, Y. (2017). Will materialism lead to happiness? A longitudinal analysis of the mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 312–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.014

Xu, Y. (2008). The Influence of Public Self-Consciousness And Materialism On Young Consumers’ Compulsive buying. Young Consumers: Insight and Ideas for Responsible Marketers, 9(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/17473610810857309

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tantawi, P.I. Materialism, life satisfaction and Compulsive Buying Behavior: An empirical investigation on Egyptian consumers amid Covid‑19 pandemic. Int Rev Public Nonprofit Mark 21, 1–25 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-022-00360-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-022-00360-4