Abstract

Surfactants for enhanced oil recovery are important to study due to their special characteristics like foam generation, lowering interfacial tension between oleic and aqueous phases, and wettability alteration of reservoir rock surfaces. Foam is a good mobility control agent in enhanced oil recovery for improving the mobility ratio. In the present work, the foaming behavior of three nonionic ethoxylated surfactants, namely Tergitol 15-S-7, Tergitol 15-S-9, and Tergitol 15-S-12, was studied experimentally. Among the surfactants, Tergitol 15-S-12 shows the highest foamability. The effect of NaCl concentration and synthetic seawater on foaming behavior of the surfactants was investigated by the test-tube shaking method. The critical micelle concentrations of aqueous solutions of the different nonionic surfactants were measured at 300 K. It was found that the critical micelle concentrations of all surfactants also increased with increasing ethylene oxide number. Dynamic light scattering experiments were performed to investigate the micelle sizes of the surfactants at their respective critical micelle concentrations. Core flooding experiments were carried out in sand packs using the surfactant solutions. It was found that 22% additional oil was recovered in the case of all the surfactants over secondary water flooding. Tergitol 15-S-12 exhibited the maximum additional oil recovery which is more than 26% after water injection.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Surfactants play a vital role in chemical flooding for their abilities to reduce interfacial tension (IFT) and to alter the wettability of reservoir rock surfaces to facilitate mobilization of trapped oil from natural reservoirs (Bera et al. 2014b; Jiang et al. 2014; Ko et al. 2014). In recent years, surfactant flooding has become one of the most useful tools in enhanced oil recovery (EOR) methods (Elraies et al. 2010; Flaaten et al. 2010; Kumar and Mohanty 2010; Santanna et al. 2009; Southwick et al. 2010). Selection of proper surfactants for EOR is an important issue in surfactant flooding for better economic recovery. Therefore, laboratory characterization of surfactants is one of the major steps before implementing EOR techniques. The main aim of the EOR process is to increase the capillary number by reducing the IFT between water and oil (Babadagli and Boluk 2005). As an effective candidate for wettability alteration, surfactants also help to contribute significantly to the production characteristics of oil during chemical flooding (Zhang et al. 2006). Due to the interrelationship between IFT and capillary number, interfacial phenomena of surfactants are studied in laboratory to screen the surfactants with respect to their activities. It has been reported the surface activities of several surface active agents and their mixtures play an important role in EOR (Babadagli 2005; Babadagli and Boluk 2005; El-Batanoney et al. 1999; Gong et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2006).

In general, foam is defined as complex, highly nonequilibrium dispersions of gas bubbles in a relatively small amount of liquid generally containing surfactants (Bera et al. 2013). The main mechanism of foam stability and foamability is the absorption of surfactants at the liquid–gas interface. As a result, the intrinsic resistance of the lamella and interfacial area are directly responsible for the foam stability in the sense of thermodynamics (Huang et al. 1986). Among the various applications of foams, their importance in EOR process is very widespread (Aveyard et al. 1994a, b; Exerowa and Kruglyakov 1998; Sadoc and Rivier 1999; Shirtcliffe et al. 2003; Zochhi 1999). For surfactant flooding, foamability and foam stability of surfactant solutions are essential. During the last few years, the effect of solid particles on foam formation and foam stability has been studied intensively. It is just noted here that the effects on foamability and foam stability of the introduction of nanoparticles are becoming of considerable interest in current research for application in oil fields. The common procedures of foam preparation include shaking (Aronson 1986; Alargova et al. 2004; Binks and Tommy 2005; Dickinson et al. 2004; Dippenaar et al. 1978; Dippenaar 1982a, b; Frye and Berg 1989; Garrett 1979; Garrett et al. 2006), bubbling (Frye and Berg 1989; Kulkarni et al. 1977; Johansson and Pugh 1992; Pugh 2005; Vijayaraghavan et al. 2006), bubbling and shaking (Frye and Berg 1989), bubbling and stirring (Aktas et al. 2008; Johansson and Pugh 1992; Schwarz and Grano 2005), and sudden drop in pressure (Dickinson et al. 2004; Kostakis et al. 2006). It was established that the particle hydrophobicity (Aktas et al. 2008; Du et al. 2003; Horozov 2008; Hunter et al. 2008), size (Aktas et al. 2008; Ata 2008; Dippenaar 1982a, b; Frye and Berg 1989; Binks and Tommy 2005), and concentration (Dippenaar 1982a, b; Gonzenbach et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2008) affect the foam stability. For foam flooding, the foamability and foam stability tests are one of the major laboratory steps for the EOR method.

In EOR, different types of surfactants are used. They have different interfacial properties for improving oil recovery. All the components of the surfactant slug are based on trial and error methods (Rosen 1989). For EOR technique, it is necessary to choose the proper surfactant with the best surface activities, i.e., ability to reduce surface tension or IFT. There has been a considerable focus on surfactant design in EOR methods. In most of the cases, anionic surfactants are used because these surfactants have several applications like emulsifiers, foam generating agents, detergents, and effective wetting agents. Depending on these adequate properties as well as low cost of anionic surfactants, they are considered as potential EOR candidates in actual reservoir cases.

In this work, foamability and foam stability of all the nonionic surfactants have been studied by the standard shaking method to understand their efficiencies as EOR candidates in different brine solutions and synthetic seawater (SSW). The critical micelle concentrations (CMCs) of the nonionic surfactants were measured at a temperature of 300 K, and a relationship between ethylene oxide numbers (EONs) and CMCs of the surfactants used has been established from the results. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments have also been performed with the surfactant solutions at their corresponding CMCs to study the sizes of the micelles of the surfactants. Core flooding experiments have been performed with the surfactant solutions. A comparison was made of the efficiencies of the surfactants to recover additional oil.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials used

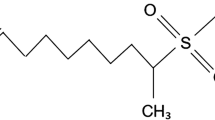

In this work, the surfactants Tergitol 15-S-7, Tergitol 15-S-9, and Tergitol 15-S-12 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany, and the chemical name of these surfactants is secondary alcohol ethoxylate. Their general structural formula is: C12-14H25-29O[CH2CH2O] x H. Table 1 shows the properties of all surfactants. The purities of the surfactants are 99.9%. The total acid number, gravity, and viscosity of the oil were found to be 0.038 mg KOH/g, 38.86°API, and 5.12 Pa s at 45 °C, respectively. The SSW was prepared by mixing different salts (NaCl, 23.54 g/L; KCl, 0.675 g/L; CaCl2, 0.115 g/L; MgCl2, 5.84 g/L; Na2SO4, 3.84 g/L; SrCl2, 0.024 g/L; KBr, 0.110 g/L; NaF, 0.090 g/L; NaHCO3, 0.200 g/L; H3BO3, 0.030 g/L) in distilled water. All these chemicals were procured from Merck Specialties Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India, and all of the chemicals are more than 98% pure. All the solutions and different concentrated brines were prepared by using reverse osmosis water from a Millipore water system (Millipore SA, 67120 Molsheim, France).

2.2 Measurement of surface tension and CMC

Surface tensions of surfactant solutions were measured with a programmable tensiometer (Kruss GmbH, Germany, model: K20 EasyDyne) using the Du Noüy ring method at 300 K. Special attention was paid to the cleaning of the platinum ring. The ring was cleaned with acetone and then flame dried for each measurement. The standard deviation was ±0.1 mN/m. For determination of CMCs of the surfactants, the concentration versus surface tension graph was plotted and the concentrations at the inflexion points of the curves are considered as CMCs of the surfactants.

2.3 DLS study of the surfactants at their CMCs

The surfactant solutions were prepared at their corresponding CMC values. The sizes of micelles were measured by a laser diffraction method using a Zetasizer version 6.00 (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Worcestershire, UK) at 300 K. The size distribution of micelles was obtained by the inbuilt software of the instrument. The software uses a reflective index (RI) of 1.465 (SBO) and a dispersant RI of 1.33 (water) during the measurement. Drops of the surfactant solution were introduced into the sample-containing cuvette, and the optimum volume was indicated by the instrument.

2.4 Foamability and foam stability tests

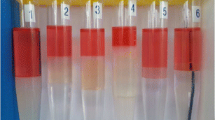

Foamability and foam stability experiments were conducted in a graduated measuring cylinder with 0.5wt% surfactant solution. We used bottle shaking tests (ASTM D-3601) to evaluate the foaming capacity of different surfactants in the presence of salts, where the volume of gas (air) is fixed in the container (centrifuge tube). Bottle shaking test (ASTM D-3601) for foam generation study is a standard method, which is reported by many authors (Schramm and Wassmuth 1994; Tamura and Kaneko 2004; Nadkarni 2007; Moayedi et al. 2014). For foam study, a constant volume of the aqueous sample in a 10-mL graduated centrifuge tube was shaken manually at a fixed frequency for fixed time (15 min for each case) and then left untouched on a flat surface (make necessary corrections for volume). The foam height and liquid holdup of the generated foam for each respective sample were recorded over time by visual observation. A plot of time versus foam volume indicates the foam stability. Foam stability was measured assuming that mechanical vibrations are absent. The foamability of the surfactant solution was measured by taking the initially produced foam volume after constant time shaking with different brine concentrations and SSW at 300 K.

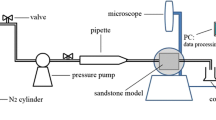

2.5 Apparatus and methods for surfactant flooding for oil recovery

A schematic of the experimental setup for surfactant flooding is shown in Fig. 1. The whole experimental setup contains a core holder for the sand pack, different cylinders for surfactant solution and crude oil, a pump from ISCO, and an effluent collecting cylinder. The core holder was fully filled with 60–70 mesh sand, and while filling the core holder brine was used to saturate the sand pack for measuring its porosity. Permeability was measured by brine flooding through the sand pack. After that the sand pack was flooded with the crude oil until water production reaches about 1% at 400 psig. The initial water saturation of the core was determined by mass balance. After water flooding, a ~ 0.6 pore volume (PV) surfactant slug was injected followed by ~ 1.25 PV water injection as chase water flooding. The above-mentioned method has also been described in our previous work in details (Bera et al. 2014a).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 CMCs and micelle sizes of the surfactants

CMC measurement of surfactant is very important for foamability and foam stability studies as well as their applications in further preliminary screening of surfactants. Before selecting a surfactant for application in oil fields, it is necessary to characterize the surfactant initially. It is well known that surfactants start to undergo micelle formation at CMCs (Hoff et al. 2001). Figure 2 shows the CMC values of the surfactants studied in this work. The present work shows that CMCs of the surfactants (Tergitol 15-S-7, Tergitol 15-S-9, and Tergitol 15-S-12) increase with increases in EON of the surfactants which shows a strong similarity to another study (Wu et al. 2006). It is found that the CMC values are 0.0031wt%, 0.0042wt%, and 0.0051wt% for the surfactants of EON of 7, 9, and 12, respectively. The data clearly illustrate the relationship between EON and CMC values of the surfactants used. For ethoxylated nonionic surfactants, the steric hindrances between head groups of the surfactants can be expected to increase with increasing EON. Subsequently with an increase in EON, the head group parameter also increases within the head group. Therefore, low EON may reduce the head group parameter as well as the area per molecule; therefore, the packing parameter is large which results in bilayer aggregates (lamella). For high EON, the head group parameter and the area per molecule increase, but the packing parameter decreases; thus, it is possible to form cylindrical micelles. With increasing EON, the packing parameter decreases and spherical micelles may be formed by decreasing the aggregation number. Therefore, the increases in head group parameter and area per molecule for nonionic surfactants with increasing EON give rise to an increase in CMC as the head group size increases. Figure 2 clearly shows that the surfactants are very active in reducing the surface tension of the liquid–air system. Among all the nonionic surfactants, Tergitol 15-S-12 shows the lowest surface tension value at its CMC. The surface tension values of the surfactant solutions at their CMCs are 31, 29, and 28 mN/m for Tergitol 15-S-7, Tergitol 15-S-9, and Tergitol 15-S-12, respectively.

It is important to consider the micelle sizes of surfactants in oil recovery processes. Figure 3 shows the size distributions of the micelles of the prepared surfactant solutions at their CMC values. The z-average diameter can be calculated in dynamic light scattering as follows (Zheng et al. 2016; Bera et al. 2012b):

where S i is the scattered intensity from particle i and D i is the diameter of particle i.

The sizes of the micelles are shown in Fig. 4. In the present study, the typical micelle sizes of the surfactants range from 0.5 μm to 10 μm which are also desired for core flooding experiments when compared to the pore size distribution of the sand grains in the sand pack model. Figure 4 shows that the micelle size of Tergitol 15-S-12 is higher than that of the other two surfactants. This is because the ethylene oxide chain length of Tergitol 15-S-12 is greater than the other two surfactants. From this study, it can be also possible to establish a relationship between the micelle sizes and CMCs of the surfactants. The results show that with an increase in CMC of the surfactant the micelle size also increases. Therefore, depending on the CMCs of the surfactants their micelle sizes can be predicted and it is possible to screen the surfactants for further investigation for implementing in EOR methods.

3.2 Foamability and foam stability

The foamability test is a special test of surfactants for their selection in EOR by foam injection. In the present work, foaming properties of nonionic surfactants were tested in pure distilled water, NaCl solutions (2wt% and 4wt%), and SSW. Figure 5 shows the foamability at 0.5 wt% of different surfactants. Results indicate that Tergitol 15-S-12 generated the highest amount of foam, i.e., higher foamability than the other nonionic surfactants used. The higher foaming properties of Tergitol 15-S-12 may be explained on the basis of higher EON. Nonionic surfactants like Tergitol 15-S-12, Tergitol 15-S-9, and Tergitol 15-S-7 can form good foam below their cloud points. Nonionic surfactants can only produce foam in good amounts when they are able to form a well-packed adsorption monolayer at the air–water interface. In the present case, the foaming is not high enough for all the surfactants and the reason is the instability of the foam films. Again, the higher foamability of Tergitol 15-S-12 compared to other nonionic surfactants can be explained on the basis of stability of monolayers. As the EON of Tergitol 15-S-12 is higher than the other nonionic surfactants, a more stable monolayer is formed and for other cases a bilayer might be favorable. As a result, Tergitol 15-S-12 shows higher foamability than the others (Patrick et al. 1997; Mittal and Shah 2002). Figure 6 shows the foaming of the Tergitol surfactants at their corresponding CMC values after several hours of equilibrium.

Adsorption of surfactants at the air–water interface plays an important role in the formation of foam and its stability. The Gibbs surface adsorption equation was used to calculate the surface excess for all the surfactants as follows (Amaral et al. 2008; Azira et al. 2008; Tan et al. 2005; Wang and Chen 2006):

where \(\varGamma\) is the surface excess, mmol/cm2; R is the universal gas constant, 8.314 J mol−1 K−1; γ is the surface tension, mN m−1; T is the thermodynamic temperature, K; and C represents the concentration of surfactant, mmol L−1 at corresponding CMC value.

The slope of the plot of logarithmic concentration of surfactant versus surface tension gives the value of \(\left( {\frac{{{\text{d}}\gamma }}{{{\text{d}}\ln C}}} \right)\). On the other hand, the molecular cross-sectional area of the polar head group (A) was calculated from the following equation:

where \(N_{\text{A}}\) indicates Avogadro’s number, 6.023 × 1023 mol−1; A is the molecular cross-sectional area of the polar head group, Å2.

Table 1 shows the calculated values of the surface excess \((\varGamma )\) and molecular cross-sectional area for all the nonionic surfactants from Eqs. (2) and (3). In our previous work, we also determined the surface excess and molecular cross-sectional area for several cationic, nonionic, and anionic surfactants (Bera et al. 2013). A significant result was found in the case of nonionic surfactant systems that as the EON of the surfactant increases the adsorption also increases. In the case of Tergitol 15-S-12, the surfactant has higher EON value and its \(\varGamma\) value is greater than that of the other surfactants (Tergitol 15-S-7 and Tergitol 15-S-9). It is also found from Table 1 that as \(\varGamma\) values increase the values of the molecular cross section of the polar head group (\(A\)) of the nonionic surfactants decrease accordingly. Surface excess is the number of moles of surfactant per unit area at the liquid–air interface. In the solution phase, most of the surfactants form a vertically monolayer just below the CMC values. The area/molecule is usually determined by the cross-sectional area of the head group. For nonionic surfactants with ethylene oxide, the area per molecule is generally much larger than other types of surfactants. Therefore, with an increase in the ethylene oxide number in the head group the area per molecule also increases. As Tergitol 15-S-12 has the highest ethylene oxide number; therefore, it has the lowest surface excess and the highest area per molecule.

The foam stability of a surfactant solution can be defined as the change in foam volume, i.e., the volume of liquid drained from the foam, per unit time (Bera et al. 2013). The foam stability of the surfactants in distilled water, 2wt% NaCl solution, 4wt% NaCl solution, and SSW is depicted in Figs. 7, 8, 9, and 10, respectively. The common way to determine the foam stability is to measure the foam volume after production of certain amount of foam with different time intervals. The foam structure is related to time which quantifies the foam stability of a certain surfactant (Kroschwitz 1994). Several factors like drainage, disproportionation, and coalescence influence the foam stability. Foam stability depends on dispersed particles of colloid in the continuous phase. These dispersed particles control the liquid drainage from the foam which significantly accounts for the high stability of a foam. Mainly these particles reduce the liquid drainage rate and increase the surface viscosity of the continuous phase. These colloid dispersions greatly affect the foam stability (Kaptay 2004; Sethumadhavan et al. 2001).

In all solutions, Tergitol 15-S-12 shows the highest foam stability. Foam stabilization is mainly caused by van der Waals forces between the molecules in the foam, electrical double layers created by dipolar surfactants (Zwitterionic surfactant) and the Marangoni effect, which acts as a restoring force to the lamellae. Other important factors that control the foam stability are surface viscosity and film elasticity. Of all the surfactants used in this study, irrespective of other influencing factors, the main controlling parameter is the surface viscosity. The surface viscosity of Tergitol 15-S-12 is high due to the presence of the high number of ethylene oxide units in the head group. The viscous nature of the surfactant solution results in a slow drainage of liquid through the bubble interfaces. As a result, the foam produced by the surfactant Tergitol 15-S-12 is also stable and shows higher stability than the other surfactants. Different salts in SSW affect the foam stability; hence, foam stability is low in the case of SSW. Some researchers suggested two different regimes of foam decay. One is during the initial stage immediately after foam formation, and the other is the comparatively slow drainage (Lunkenheimer and Malysa 2003; Carey and Stubenrauch 2009). The produced thin films in the air–water interface indicate the foam stability. Foam stability and quality of foam are very important in oil recovery to increase the sweep efficiency. Therefore, laboratory study of foam stability is a crucial step for foam flooding for EOR.

3.3 Surfactant flooding and oil recovery

Surfactants are considered to be important chemicals for tertiary recovery by reducing IFT and changing wettability of rock surfaces. In the present work, surfactant solutions were injected into the sand pack after water flooding. Due to the high porosity of the sand pack (~37%), water flooding is able to produce high recovery (~52%). Figure 11 shows the performances of surfactants in oil recovery after injection of different pore volumes into the sand pack and the variations of oil and water cuts. Figure 11 shows that after injection of 1.15 PV water the oil cut decreases to 5% and the water cut goes to 95%. At this moment, the surfactant injection is started and it is found that the water cut declines gradually and the oil cut again increases to produce the highest recovery. The enhanced recovery can be explained on the basis of IFT reduction or increase in capillary number and consequent mobilization of the oil trapped inside pore throats. As a result, the oil saturation increases due to coalescence of oil drops and retrapping of oil drops mobilized from the oil bank by the surfactant slug. Figure 11 also shows that the additional of recovery by Tergitol 15-S-12 is higher than others due to significant interfacial surface active properties of the surfactant. On the other hand, due to the presence of 12 ethylene oxide groups in Tergitol 15-S-12, the micelle size is larger than the other two surfactants. Therefore, the micelles formed by surfactant Tergitol 15-S-12 are more stable than those of the other two favored by the entropy and enthalpy of micellization. Therefore, during surfactant flooding for Tergitol 15-S-9 and Tergitol 15-S-7 it is difficult to form micelles in the system and they cannot reduce the IFT as required. The oil trapped in the porous matrix cannot be recovered easily, and residual oil saturation remains high. As Tergitol 15-S-12 can produce a microemulsion easily, it is also able to produce ultra-low IFT and shows higher additional oil recovery as described in the oil recovery section. It is also worth mentioning at this point that the foaming property of Tergitol 15-S-12 is better than other surfactants and as a result Tergitol 15-S-12 shows higher oil recovery than the other surfactants. Therefore, a bridge can be established from all the studies of surfactant solutions and their influences on oil recovery to provide an overview of the importance and significance of this work. The additional recovery was 22.3, 24.6, and 26.9% for Tergitol 15-S-7, Tergitol 15-S-9, and Tergitol 15-S-12, respectively. The detail of the surfactant flooding results with properties of the sand pack is given in Table 2.

Another important mechanism that plays a vital role in oil recovery is wettability alteration by surfactants (Bera et al. 2012a, 2015). Oil–water relative permeabilities are highly influenced by wettability alteration during surfactant flooding through an oil-saturated sand pack. Surfactant flooding enhances the relative permeability of oil as the oil-wet state of the sand pack is altered to a water-wet state. As a result, flows of oil and water through the sand pack are changed accordingly. Water finds the path to move forward along the pore wall with water-wet state and reaches the center of the pores in the oil-wet state during the surfactant flooding. Therefore, the capillary forces act along the direction of water flooding for a water-wet surface and the opposite for an oil-wet surface. This phenomenon also reflects the increase in displacement efficiency by surfactant flooding which enhances the oil recovery after water flooding. As the sand pack is water-wet in general, injection of the surfactant solution can recover more oil from the oil-saturated core during surfactant flooding by alteration of wettability toward a water-wet state. So surfactant flooding can reduce the residual oil saturation. Therefore, after water flooding in an oil field surfactant flooding can significantly recover the residual oil.

Apart from the wettability alteration, in situ microemulsion formation during surfactant flooding causes increased oil recovery (Glinsmann 1979; Jeirani et al. 2014). During surfactant flooding, a multiphase microemulsion system is formed by mixing the surfactant slug with the remaining oil in the reservoir after water flooding. As the microemulsion is formed, IFT between the oil and surfactant slug reduces to ultra-low one which helps to increase the capillary number followed by enhanced oil recovery. The in situ generated microemulsion is assumed to disseminate toward the producing well by sweeping a significant amount of oil in the reservoir. The process depends on the compositions present in the surfactant solution and overall compositions of the formed microemulsion system.

4 Conclusions

Present studies of micellization and sizes of micelles, foamability and foam stability of different nonionic surfactants provide a sound background for selection and application of surfactants for EOR. Based on the results of the work, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

1.

Tergitol 15-S-12 shows maximum foamability in distilled water, NaCl solutions of different concentrations, and SSW.

-

2.

The present study provides useful information for selection of surfactant systems for EOR. When the molecular cross section of the polar head group (\(A\)) decreases, the surface excess (\(\varGamma\)) value increases for all the nonionic surfactants.

-

3.

DLS study shows that with an increase in EON of the surfactants the micelle sizes of the surfactants also increase at their corresponding CMCs.

-

4.

The additional recovery is more than 22%. The surfactant with the highest EON value, Tergitol 15-S-12, shows the greatest efficiency to recover more than 26% additional oil compared to straight water flooding.

References

Aktas Z, Cilliers JJ, Banford AW. Dynamic froth stability: particle size, airflow rate and conditioning time effects. Int J Miner Process. 2008;87(1–2):65–71. doi:10.1016/j.minpro.2008.02.001.

Alargova RG, Warhadpande DS, Paunov VN, et al. Foam superstabilization by polymer microrods. Langmuir. 2004;20(24):10371–4. doi:10.1021/la048647a.

Amaral MH, Neves JD, Oliveria AZ, et al. Foamability of detergent solutions prepared with different types of surfactants and waters. J Surfactants Deterg. 2008;11:275–8. doi:10.1007/s11743-008-1088-0.

Aronson MP. Influence of hydrophobic particles on the foaming of aqueous surfactant solutions. Langmuir. 1986;2(5):653–9. doi:10.1021/la00071a023.

Ata S. Coalescence of bubbles covered by particles. Langmuir. 2008;24(12):6085–91. doi:10.1021/la800466x.

Aveyard R, Binks BP, Fletcher PDI, et al. Aspects of aqueous foam stability in the presence of hydrocarbon oils and solid particles. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 1994a;48:93–120. doi:10.1016/0001-8686(94)80005-7.

Aveyard R, Binks BP, Fletcher PDI, et al. Contact angles in relation to the effects of solids on film and foam stability. J Dispers Sci Technol. 1994b;15(3):251–71. doi:10.1080/01932699408943557.

Azira H, Tazerouti A, Canselier JP. Study of foaming properties and effect of the isomeric distribution of some anionic surfactants. J Surfactants Deterg. 2008;11(4):279–86. doi:10.1007/s11743-008-1093-3.

Babadagli T. Analysis of oil recovery by spontaneous imbibitions of surfactant solution. Oil Gas Sci Technol Rev. 2005;60(4):697–710. doi:10.2516/ogst:2005049.

Babadagli T, Boluk Y. Oil recovery performances of surfactant solutions by capillary imbibitions. J Colloids Interface Sci. 2005;282(1):162–75. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2004.08.149.

Bera A, Kissmathulla S, Ojha K, et al. Mechanistic study of wettability alteration of quartz surface induced by nonionic surfactants and interaction between crude oil and quartz in presence of sodium chloride salt. Energy Fuels. 2012a;26(6):3634–43. doi:10.1021/ef300472k.

Bera A, Kumar S, Mandal A. Temperature-dependent phase behavior, particle size, and conductivity of middle-phase microemulsions stabilized by ethoxylated nonionic surfactants. J Chem Eng Data. 2012b;57(12):3617–23. doi:10.1021/je300845q.

Bera A, Kumar T, Ojha K, et al. Screening of microemulsion properties for application in enhanced oil recovery. Fuel. 2014a;121:198–207. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2013.12.051.

Bera A, Mandal A, Guha BB. Effect of synergism of surfactant and salt mixture on interfacial tension reduction between crude oil and water in enhanced oil recovery. J Chem Eng Data. 2014b;59(1):89–96. doi:10.1021/je400850c.

Bera A, Mandal A, Kumar T. Effect of rock-crude oil-fluid interactions on wettability alteration of oil-wet sandstone in presence of surfactants. Pet Sci Technol. 2015;33(5):542–9. doi:10.1080/10916466.2014.998768.

Bera A, Ojha K, Mandal A. Synergistic effect of mixed surfactant systems on foam behavior and surface tension. J Surfactants Deterg. 2013;16(4):621–30. doi:10.1007/s11743-012-1422-4.

Binks BP, Tommy SH. Aqueous foams stabilised solely by silica nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44(24):3722–5. doi:10.1002/anie.200462470.

Carey E, Stubenrauch C. Properties of aqueous foams stabilized by dodecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;333(2):619–27. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2009.02.038.

Dickinson E, Ettelaie R, Kostakis T, et al. Factors controlling the formation and stability of air bubbles stabilized by partially hydrophobic silica nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2004;20(20):8517–25. doi:10.1021/la048913k.

Dippenaar A. The destabilization of froth by solids. I. The mechanism of film rupture. Int J Miner Process. 1982a;9(1):1–14. doi:10.1016/0301-7516(82)90002-3.

Dippenaar A. The destabilization of froth by solids. II. The rate-determining step. Int J Miner Process. 1982b;9(1):15–22. doi:10.1016/0301-7516(82)90003-5.

Dippenaar A, Harris PJ, Nicol MJ. The effect of particles on the stability of flotation froths. Rep. Natl. Inst. Metall. South Africa, 34 pp, 1978.

Du Z, Bilbao-Montoy MP, Binks BP, et al. Outstanding stability of particle-stabilized bubbles. Langmuir. 2003;19(8):3106–8. doi:10.1021/la034042n.

El-Batanoney M, Abdel-Monghny T, Ramazi M. The effect of mixed surfactants on enhancing oil recovery. J Surfactants Deterg. 1999;2(2):201–5. doi:10.1007/s11743-999-0074-7.

Elraies KA, Tan IM, Awang M, et al. A new approach to low-cost, high performance chemical flooding system. In: SPE production and operation conference and exhibition, June 8–10, Tunis, Tunisia; 2010. doi:10.2118/133004-MS.

Exerowa DR, Kruglyakov PM. Foams and foam films. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1998.

Flaaten AK, Nguyen QP, Zhang J, et al. Alkaline/surfactant/polymer chemical flooding without the need for soft water. SPE J. 2010;15(1):184–96. doi:10.2118/116754-PA.

Frye GC, Berg JC. Antifoam action by solid particles. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1989;127(1):222–38. doi:10.1016/0021-9797(89)90023-4.

Garrett PR. The effect of polytetrafluoroethylene particles on the foamability of aqueous surfactant solutions. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1979;69(1):107–21. doi:10.1016/0021-9797(79)90085-7.

Garrett PR, Wicks SP, Fowles E. The effect of high volume fractions of latex particles on foaming and antifoam action in surfactant solutions. Colloids Surf A. 2006;282–283:307–28. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2006.01.054.

Glinsmann GR. Surfactant flooding with microemulsions formed in situ—effect of oil characteristics. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, September 23-26, Las Vegas, Nevada, 1979. doi:10.2118/8326-MS.

Gong Y, Li Z, An J. The properties of sodium naphthalene sulfonate in lowering interfacial tension and its possibility of application in EOR. J Dispersion Sci Technol. 2005;26(4):503–7. doi:10.1081/DIS-200054612.

Gonzenbach UT, Studart AR, Tervoort E, et al. Ultrastable particle-stabilized foams. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45(21):3526–30. doi:10.1002/anie.200503676.

Hoff E, Nystrom B, Lindman B. Polymer–surfactant interactions in dilute mixtures of a nonionic cellulose derivative and an anionic surfactant. Langmuir. 2001;17(1):28–34. doi:10.1021/la001175p.

Horozov TS. Foams and foam films stabilized by solid particles. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2008;13(3):134–40. doi:10.1016/j.cocis.2007.11.009.

Huang D, Nimolvo A, Wasan D. Foams: basic properties with applications to porous media. Langmuir. 1986;2(5):672–7. doi:10.1021/la00071a027.

Hunter TN, Pugh RJ, Franks GV, et al. The role of particles in stabilizing foams and emulsions. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2008;137(2):57–81. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2007.07.007.

Jeirani Z, Mohamed Jan B, Si Ali B, et al. In-situ prepared microemulsion-polymer flooding in enhanced oil recovery—a review. J Pet Sci Technol. 2014;32(2):240–51. doi:10.1080/10916466.2011.588644.

Jiang P, Li N, Ge J, et al. Efficiency of a sulfobetaine-type surfactant on lowering IFT at crude oil-formation water interface. Colloids Surf A. 2014;443:141–8. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2013.10.061.

Johansson G, Pugh RJ. The influence of particle size and hydrophobicity on the stability of mineralized froths. Int J Miner Process. 1992;34(1–2):1–21. doi:10.1016/0301-7516(92)90012-L.

Kaptay G. Interfacial criteria for stabilization of liquid foams by solid particles. Colloids Surf A. 2004;230(1–3):67–80. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2003.09.016.

Ko KM, Chon BH, Jang SB, et al. Surfactant flooding characteristics of dodecyl alkyl sulfate for enhanced oil recovery. J Ind Eng Chem. 2014;20(1):228–33. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2013.03.043.

Kostakis T, Ettelaie R, Murray BS. The effect of high salt concentrations on the stabilization of bubbles by silica particles. Langmuir. 2006;22(3):1273–80. doi:10.1021/la052193f.

Kroschwitz JI. Kirk-Othmer encyclopedia of chemical technology. 4th ed. New York: Wiley; 1994.

Kulkarni RD, Goddard ED, Kanner B. Mechanism of antifoaming: role of filler particle. Ind Eng Chem Fundam. 1977;16(4):472–4. doi:10.1021/i160064a014.

Kumar R, Mohanty KK. ASP flooding of viscous oils. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, September 19–22, Florence, Italy; 2010. doi:10.2118/-135265-MS.

Lunkenheimer K, Malysa K. A simple automated method of quantitative characterization of foam behaviour. Polymer Int. 2003;52(4):536–54. doi:10.1002/pi.1105.

Mittal KL, Shah DO, editors. Adsorption and aggregation of surfactants in solution. Basel: CRC Press; 2002.

Moayedi M, James LA, Mahmoodi M. An experimental study on optimization of SAG process utilizing nonionic surfactants and sodium lignosulfonate. In: International symposium of the society of core analysts, 8–11 September Avignon, France, 2014, SCA2014-087.

Nadkarni RAK. Guide to ASTM test methods for the analysis of petroleum products and lubricants. ASTM manual series; no. mnl44-2nd, West Conshohocken, PA, p. 111, 2007.

Patrick HN, Warr GG, Manne S, Aksay IA. Self-assembly structures of nonionic surfactants at graphite/solution interfaces. Langmuir. 1997;13(16):4349–56. doi:10.1021/la9702547.

Pugh RJ. Experimental techniques for studying the structure of foams and froths. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2005;114–115:239–51. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2004.08.005.

Rosen MJ. Selection of surfactant pairs for optimization of interfacial properties. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1989;66(12):1840–3. doi:10.1007/BF02660759.

Sadoc JF, Rivier N, editors. Foams and emulsions NATO ASI series E, vol. 354. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 1999.

Santanna VC, Curbelo FDS, Castro Dantas TN, et al. Microemulsion flooding for enhanced oil recovery. J Pet Sci Eng. 2009;66(3–4):117–20. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2009.01.009.

Schramm LL, Wassmuth F. Foams: basic principles. foams: fundamentals and applications in the petroleum industry. In: Schramm LL, editor. Advances in chemistry series 242. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1994. p. 3–45.

Schwarz S, Grano S. Effect of particle hydrophobicity on particle and water transport across a flotation froth. Colloids Surf A. 2005;256(2–3):157–64. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2005.01.010.

Sethumadhavan GN, Nikolov AD, Wasan DT. Stability of liquid films containing monodisperse colloidal particles. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2001;240(1):105–12. doi:10.1006/jcis.2001.7628.

Shirtcliffe NJ, McHale G, Newton MI, et al. Intrinsically superhydrophobic organosilica sol–gel foams. Langmuir. 2003;19(13):5626–31. doi:10.1021/la034204f.

Southwick JG, Svec Y, Chilek G, et al. The effect of live crude on alkaline–surfactant–polymer formulations: implications for final formulation design. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, September 19-22, Florence, Italy; 2010. doi:10.2118/135357-MS.

Tamura T, Kaneko Y. Foam film stability in aqueous systems. In: Hartland S, editors. Surface and interfacial tension: measurement, theory, and applications. Surfactant Science Series 119, CRC Press, New York, p. 90, 2004.

Tan SN, Fornasiero D, Sedev R, et al. The role of surfactant structure on foam behavior. Colloids Surf A. 2005;263(1–3):233–8. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2004.12.060.

Vijayaraghavan K, Nikolov A, Wasan D. Foam formation and mitigation in a three-phase gas-liquid-particulate system. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2006;123–126:49–61. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2006.07.006.

Wang HR, Chen KM. Preparation and surface active properties of biodegradable dextrin derivative surfactants. Colloids Surf A. 2006;281(1–3):190–3. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2006.02.039.

Wu Y, Shuler PJ, Blanco M, et al. An experimental study of wetting behavior and surfactant EOR in carbonates with model components. In: SPE/DOE symposium on improved oil recovery, April 22–26, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 2006. doi: 10.2118/99612-PA.

Zhang DL, Shunhua L, Puerto M, et al. Wettability alteration and spontaneous imbibitions in oil-wet carbonate formations. J Pet Sci Eng. 2006;52(1–4):213–26. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2006.03.009.

Zhang S, Sun D, Dong X, et al. Aqueous foams stabilized with particles and nonionic surfactants. Colloids Surf A. 2008;324(1–3):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2008.03.020.

Zheng T, Bott S, Huo Q. Techniques for accurate sizing of gold nanoparticles using dynamic light scattering with particular application to chemical and biological sensing based on aggregate formation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(33):21585–94. doi:10.1021/acsami.6b06903.

Zochhi G. In: Broze G, editors. Handbook of detergents, part A: properties. Surfactant science series. vol. 59, Marcel Dekker, New York, 1999.

Acknowledgements

The first author (AB) thanks the Petroleum Institute, Abu Dhabi, for providing the fellowship for his postdoctoral research. The second author (AM) gratefully acknowledges the financial support provided by Council for Scientific and Industrial Research [22(0649)/13/EMR-II], New Delhi, to the Department of Petroleum Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology (Indian School of Mines), Dhanbad, India.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Edited by Yan-Hua Sun

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bera, A., Mandal, A., Belhaj, H. et al. Enhanced oil recovery by nonionic surfactants considering micellization, surface, and foaming properties. Pet. Sci. 14, 362–371 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-017-0156-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-017-0156-3