Abstract

The purpose of this study is to identify the latent profiles of Chinese adolescents’ family (parent–adolescent and sibling) relationships prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as associations between those profiles and adolescents’ emotional and behavioral responses. A total of 2,305 adolescents from China aged between 10 and 18 years completed measures of parent–adolescent relationships, sibling relationships, and emotional and behavioral responses during the pandemic. Four profiles of family relationships were identified via latent profile analysis and categorized as Cohesive-Decline, Mild-Decline, Conflictual-Stable, and Indifferent-Stable. Adolescents with a Conflictual-Stable profile reported more emotional and behavioral responses compared to the other profiles. In contrast, adolescents with a Cohesive-Decline profile exhibited fewer emotional responses compared to the other profiles. Adolescents with a Mild-Decline profile had fewer emotional responses than those with an Indifferent-Stable profile. These results shed light on the patterns and consequences of family relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic and have substantial implications for interventions involving family relationships in the context of regular epidemic prevention and control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) spread rapidly in the first quarter of 2020 and, in March 2020, was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020). To control the spread of COVID-19, the Chinese government imposed rigorous social distancing measures, including stay-at-home policies, school closures, and travel restrictions (Adhikari et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2020). In many instances, these constraints restricted adolescents’ activities to the home setting, limiting their interactions and communications to include sole family members (Prime et al., 2020; Sevilla & Smith, 2020). Higher levels of communication and interaction result in either greater family cohesion (Lindgaard et al., 2009) or increased family conflict (Su et al., 2018). Previous studies demonstrated adolescents were more vulnerable to emotional (e.g., fear) and behavioral (e.g., compulsive cleaning) problems than adults in response to health threats (Babore et al., 2020; Rains et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Woods et al., 2020). However, these effects are influenced by the quality of family relationships (Lee et al., 2021; Walsh, 2016), with increased warmth serving as a protective factor and increased conflict as a risk factor (Browne et al., 2015; Prime et al., 2020). Although changes in adolescents’ family relationships during the pandemic and the possible impact of those changes have been discussed in some research (Ayuso et al., 2020; Brock & Laifer, 2020; Prime et al., 2020), few studies have utilized a person-centered approach to examine whether adolescents’ relationship patterns with diverse family members were affected diversely by the pandemic. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether family relationship patterns are related to adolescents’ responses to the pandemic. The present study fills these gaps through a person-centered approach and examining the patterns of the changes of various family relationships (i.e., parent–adolescent and sibling relationships) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the association between family relationship patterns and adolescents’ emotional and behavioral responses to the pandemic. Identifying family relationship patterns and their influence may inform targeted interventions and services for adolescents in the context of regular epidemic prevention and control.

Family theories and factor-analytic research have differentiated two dimensions of family relationships: positive aspects, such as warmth, and negative aspects, such as conflict (Buhrmester & Furman, 1990; Denissen et al., 2009). Relationship warmth refers to the degree of intimacy, closeness, and trust among family members (Sanders, 2004). Contrastively, relationship conflict is typically characterized by interactions involving quarrels, antagonism, and anger (Sanders, 2004). According to the emotional security theory, warmth in family relationships enables children and adolescents to build emotional security (Alegre et al., 2014), whereas adolescents perceive frequent family conflicts as threatening and emotionally insecure (Cummings & Miller-Graff, 2015). Perceived family relationship warmth has been found to reduce the risk of emotional distress and behavioral adjustment difficulties (Kenny et al., 2013; Raudino et al., 2013). Family warmth has also been demonstrated to buffer the effects of adversity on adolescents’ emotional symptoms (Shahar & Henrich, 2016). Thus, relationship warmth supposedly serves as a protective factor against stressful life events, such as the outbreak of COVID-19. Likewise, relationship conflict is a risk factor for stress responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (Sinko et al., 2021). Empirical evidence indicates that conflicts with parents aggravated adolescents’ emotional problems during the pandemic (Lee et al., 2021). However, relationship conflict has been recognized as a stronger predictor of adolescent adjustment than warmth (Buist et al., 2013; Cummings et al., 2020). As both warmth and conflict are suggested to be associated with adolescents’ emotional and behavioral responses to the COVID-19 pandemic—and, of these, conflict might have a more substantial effect—the present study examined both aspects of family relationships.

Majority of previous studies in this area have concentrated on parent–adolescent relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Cooper et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021), overlooking the role of other family relationships, such as sibling relationships (Prime et al., 2020). According to family system theory, family relationships (e.g., parent–adolescent and sibling relationships) interact with one another and exist as a subsystem that itself affects family members (Miller et al., 2000). Specifically, prior research indicates that the quality of sibling relationships is influenced by parent–adolescent relationships, as spillover theory and compensate theory proposed (Jenkins et al., 2012). Warmth and conflict in parent–adolescent relationships may “spillover” into sibling relationships (the congruence hypothesis) or compensate for parent–adolescent relationships (the compensation hypothesis; Boer et al., 1992; Kim et al., 2006; Whiteman et al., 2011). Some research indicates that high levels of parent–adolescent conflict are associated with increased sibling conflict (Kim et al., 2006), whereas other research suggests that siblings possibly seek security from each other and bond tightly to compensate for difficult parent–adolescent relationships (Whiteman et al., 2011). Spillover of negative emotions is expected during the pandemic since frequent conflicts and a lack of warmth in parent–adolescent relationships have been shown to impair sibling relationships due to changes in parenting behavior (Kretschmer & Pike, 2009; Prime et al., 2020). However, the COVID-19 pandemic is distinct from other short-term disasters (e.g., earthquakes) in that it required adolescents to stay at home, where they could obtain social support only from family members (Brock & Laifer, 2020). This benefits sibling relationships, particularly when siblings receive equally negative treatment (Feinberg et al., 2003). Adolescents who had conflictual relationships with their parents exhibited fewer problem behaviors when they had warm sibling relationships, as suggested by compensate theory (Davies et al., 2019). Such findings might be applied to effectively identify the subgroup(s) of adolescents most at risk of being affected by the pandemic. As such, the current study used a person-centered approach to identify higher-risk and lower-risk patterns in family relationships.

As some reviews have suggested that the quality of family relationships might have deteriorated during the pandemic (Brock & Laifer, 2020; Prime et al., 2020), it is necessary to consider changes in family relationships as a consequence of the pandemic. Due to school closures and stay-at-home policies (Pan et al., 2020), adolescents are more likely to spend more time using electronic devices for information gathering or entertainment, increasing the risk of problematic Internet use (Chen et al., 2020). This perhaps results in increased anger and quarrels between parents and adolescents (Özaslan et al., 2021). Moreover, when adolescents spend more time on screens, other family members experience a greater sense of neglect and a lack of warmth (Williams & Merten, 2011). However, not all adolescents demonstrated problematic behaviors during the pandemic; variance is expected at the family level with regard to the extent of changes in relationship warmth and conflict (Lindgaard et al., 2009; Prime et al., 2020). In other words, different families are expected to exhibit different patterns of relationship change.

Additionally, some evidence indicates that adolescents in cohesive families have higher levels of psychosocial adjustment (Buist & Vermande, 2014), whereas those in distressed or conflictual families are more likely to experience emotional and behavioral problems (Xia et al., 2020). However, to our knowledge, no prior study has yet investigated the patterns of family relationship change and their implications for emotional and behavioral responses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Person-centered approaches such as latent profile analysis (LPA) emphasize heterogeneity among individuals (Sturge-Apple et al., 2014) and have been used to classify families based on their characteristics (Xia et al., 2020). Accordingly, the present study used LPA to capture patterns in family relationship quality and changes over the pre– and post–COVID-19 period. Moreover, to emphasize the importance of family relationships with regard to adolescents’ reactions to the pandemic, we examined family relationship patterns in predicting emotional and behavioral responses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study explored adolescents’ family relationship patterns as well as the associations between those relationship patterns and adolescents’ emotional and behavioral responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, this study investigated the heterogeneous patterns of adolescents’ perceived warmth and conflict in their present and retrospective parent–adolescent and sibling relationships using LPA. Due to the exploratory nature of LPA, no hypothesize was proposed regarding to the number of relationship patterns. The second purpose of this study was to investigate whether relationship patterns are associated with adolescents’ emotional and behavioral responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on the current literature, we hypothesized that negative responses would differ across relationship categories.

Methods

Participants and procedures

An online survey was conducted on a Chinese survey website (www.wjx.cn) to investigate adolescents’ family relationship patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were recruited using convenience sampling via WeChat, a popular social media platform. After completing the online questionnaire, all participants received 10 CNY (approximately 1.43 USD) as compensation for participation. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Normal University. Data collection took place from March 1 to April 5, 2020, in Mainland China.

A total of 3,955 teenagers voluntarily participated in the investigation, 2,305 of whom were included in the final sample. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged between 10 and 18 years; (2) currently living with at least one parent; and (3) currently living with at least one sibling. Of the final sample, 54.6% were girls (n = 1,259) and 45.4% were boys (n = 1,046), and their average age was 12.28 years (SD = 1.98).

Measures

Demographic statistics

Demographic information was collected based on respondents’ self-reported gender (0 = male; 1 = female), age, parents’ education level (1 = secondary school or below; 2 = high school; 3 = junior college; 4 = undergraduate; 5 = graduate or above), and family income level (1 = far below average; 2 = below average; 3 = average; 4 = above average; 5 = far above average).

Relationships with parents and siblings

In the current study, parent–adolescent relationships and sibling relationships were each assessed using eight self-developed items. Self-developed questionnaires were employed to control the total length of the questionnaire and to ensure a high completion rate during the emergency timepoint of the COVID-19 outbreak. Four items measured relationship warmth (intimacy, communication, trust, and satisfaction), and four items measured relationship conflict (anger, quarrels, ignoring, and antipathy). Participants were asked to rate their relationships prior to and during the pandemic. Responses for items measuring relationship warmth ranged from 1 (very low) to 7 (very high), and those for items measuring relationship conflicts ranged from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Total scores for the four corresponding item groups indicated relationship warmth or conflict, respectively. The internal consistencies of both aspects of each relationship type ranged from 0.89 to 0.95.

Emotional responses

Emotional responses during the COVID-19 pandemic were measured using five self-developed items (panic, lonely, anxious, depressed, and angry). Responses were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The mean score on the entire scale indicated the level of emotional response during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cronbach’s α was 0.91, indicating excellent reliability.

Behavioral responses

We developed a three-item scale assessing participants’ negative behavioral responses during the COVID-19 pandemic. The items in this scale were “Cannot stop washing hands and sanitizing during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic,” “Cannot stop checking news about COVID-19 on the phone,” and “Cannot sleep well or eat well during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.” Responses to these questions were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The mean score for the entire scale indicated the level of negative behavioral responses during the COVID-19 pandemic. The scale’s internal consistency was 0.70, indicating good reliability.

Statistical analyses

First, LPA was conducted to investigate the relationship patterns for parent–adolescent relationships and sibling relationships prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic using Mplus (version 7.4). LPA is a person-centered analysis that was performed to identify latent groups formed based on the patterns of participants’ relationships with parents and siblings at the time of the study and prior to the pandemic. In this analysis, the Akaike information criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1974), Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), adjusted BIC (ABIC; Sclove, 1987), bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT; McLachlan et al., 2019), and entropy were used to identify the best-fitting model (Nylund et al., 2007). Lower AIC, BIC, and ABIC values and greater entropy (i.e., close to 1) indicate better fit and classification accuracy, respectively (Geiser, 2012). When entropy is equal to or greater than 0.8, classification accuracy reaches 90% (Nylund et al., 2007). A statistically significant p-value for the BLRT or LMR means that the k-class model is a better fit than the k-1 class model (McLachlan et al., 2019). Second, multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) and a three-step method were performed to examine the associations of latent profile membership with participants’ relationships, emotional responses, and behavioral responses.

Results

Demographic, descriptive, and correlation statistics

Participants’ demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A high percentage participants’ parents had low educational attainment: only 26.81% of participants’ mothers and 20.57% of participants’ fathers had graduated from high school or held a higher degree. A total of 70.54% of participants (n = 1,626) reported that their family income was at average level, while only 3.34% rated their families above average level (n = 77).

Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) and correlations of key variables are shown in Table 2. Correlations between all family relationships were significant (r range = − 0.52 to 0.89, p < 0.001). Parent–adolescent and sibling warmth were negatively correlated with participants’ emotional responses (r range = − 0.13 to − 0.10, p < 0.001), while parent–adolescent and sibling conflicts were positively correlated with participants’ emotional responses (r range = 0.23 to 0.27, p < 0.001). Behavioral responses were positively correlated with parent–adolescent and sibling conflicts, but relationship warmth was not significantly related to behavioral responses (p > 0.05).

Latent profile analysis and profile characteristics

LPA was conducted by increasing the number of classes and gauging model indices to classify latent groups for parent–adolescent relationships and sibling relationships (Table 3). As the number of classes increased, the AIC, BIC, and ABIC values decreased, and the BLRT results were statistically significant. However, the LMR values were not significant in the five-class model, indicating that the four-class model was more parsimonious and preferable. The entropy value was 0.92 for the four-class model, which was higher than that for the three-class model. Therefore, the four-class model was determined to be the best model to fit the data (Bolded in Table 3).

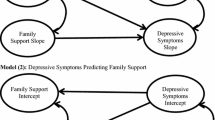

The four latent groups were named according to their level and change of relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 1; Appendix A). The first profile was labeled “Cohesive-Decline” (n = 1,225, 53.14%). Participants with this profile showed high levels of relationship warmth and low levels of relationship conflict. However, their parent–adolescent and sibling relationships worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, except for parent–adolescent warmth (parent–adolescent conflict: t(1,224) = 10.27, p < 0.001; sibling conflict: t(1,224) = 5.66, p < 0.001; parent–adolescent warmth: t(1,224) = − 3.80, p < 0.001). The second profile was labeled “Mild-Decline” (n = 568, 24.64%). Participants with this profile showed relatively high levels of relationship warmth and low levels of relationship conflict. Although sibling warmth improved (t(568) = 4.01, p < 0.001), parent–adolescent and sibling conflicts became more frequent (parent–adolescent: t(568) = 7.67, p < 0.001; sibling: t(568) = 3.94, p < 0.001). The third profile was labeled “Conflictual-Stable” (n = 236, 10.24%). Participants with this profile reported high levels of warmth and conflict in both relationships. No significant relationship quality change was founded. The last profile was labeled “Indifferent-Stable” (n = 276, 11.97%). Participants with this profile reported medium levels for all relationships, and their relationships also did not significantly change.

Profiles and outcomes

The characteristics of the four-profile solution revealed by MANOVA are shown in Table 4. The F-test and Bonferroni post-hoc comparison showed significant differences in study variables across latent profiles. Specifically, individuals belonging to Cohesive-Decline profile scored higher on relationship warmth and reported fewer conflicts than those belonging to other three profiles (p < 0.001). Additionally, individuals belonging to Conflictual-Stable and Indifferent-Stable profiles reported more parent–adolescent conflicts than those belonging to Cohesive-Decline and Mild-Decline profiles. Individuals belonging to Indifferent-Stable profile reported less parent–adolescent and sibling warmth than other three profiles (p < 0.001). Adolescents with Conflictual-Stable profile reported most parent–adolescent and sibling conflict (p < 0.001).

Next, a three-step method was adopted to examine the associations between latent profile membership and emotional and behavioral responses during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 4; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014). For the emotional responses, analyses indicated statistically significant differences across the four profiles (χ2 = 120.89, p < 0.001). Group comparison results showed that those with the Conflictual-Stable profile (Profile 3) had the most emotional responses, followed by those with the Indifferent-Stable (Profile 4), Mild-Decline (Profile 2), and finally Cohesive-Decline (Profile 1) profiles. For the behavioral responses, a significant main effect was also detected (χ2 = 22.03, p < 0.001). Group comparison results showed that participants with the Indifferent-Stable profile (Profile 4) had more behavioral responses than the other three profiles.

Discussion

The current study extended research on patterns of parent–adolescent and sibling relationships to a sample of Chinese adolescents during the pre– and post–COVID-19 period. Using a person-centered approach, we found four distinct profiles of parent–adolescent and sibling relationships: Cohesive-Decline, Mild-Decline, Conflictual-Stable, and Indifferent-Stable. Adolescents with a Cohesive-Decline profile reported fewer emotional and behavioral responses, while those with a Conflictual-Stable profile were more likely to experience emotional and behavioral responses. In contrast to variable-centered approaches, the results of LPA highlighted variations across family profiles through differentiating parent–child and sibling relationships’ quality. These findings add to the evidence for the spillover hypothesis and emotional insecure theory that family relationships are associated with each other as well as adolescents’ emotional and behavioral responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. This provides a new perspective to understand family relationships in China and their transformations in this unique period. The present study also has practical implications regarding identifying at-risk adolescents with conflictual family relationships and informing interventions focusing on family relationships in the context of regular epidemic prevention and control.

By integrating family relationships before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, our findings revealed four family relationship profiles, including Cohesive-Decline, Mild-Decline, Conflictual-Stable and Indifferent-Stable. The majority of adolescents (Cohesive-Decline profile, Mild-Decline profile, 78%) experienced worsen family relationships characterized by increasing conflicts. This is consistent with what has been found in previous study that stay-at-home policy indirectly contributed to heated arguments in families (Sinko et al., 2021). One potential explanation is that adolescents were more prone to engage in problematic internet use due to social distancing measures (Chen et al., 2020). The participants in our study were from China, whose parents place a high premium on adolescents’ academic achievement, promoting parents to closely monitor and control their children’s internet usage (Prime et al., 2020). According to self-determination theory, parental control behaviors are likely to exacerbate adolescent autonomy frustration, escalating conflict between parents and adolescents (Van Petegem et al., 2015). Notably, adolescents with Conflictual-Stable or Indifferent-Stable profiles reported no significant changes in these relationships. This finding demonstrates the heterogeneity of family relationship change by revealing that adolescents with Conflictual-Stable or Indifferent-Stable profiles were less sensitive to changes in family relationships due to their prior exposure to a high level of conflict before the pandemic (Solmeyer & Feinberg, 2011).

Our findings that the degrees of warmth and conflict with parents and siblings were similar in each profile support the congruence (spillover) hypothesis and attachment theory (Ainsworth & Bowlby, 1991; Whiteman et al., 2011), which postulate that adolescents develop internal working models of attachment based on their relationships with their parents and behave in the same way in their sibling relationships. This result was corroborated by empirical studies that demonstrated the positive correlation between parent–adolescent relationship and sibling relationships (Hakvoort et al., 2010). However, the casual relationship between these family relationships should be inferred cautiously due to the cross-sectional design of our study. Our results also indicate a concurrent increase in parent–adolescent and sibling conflicts in the Cohesive-Decline and Mild-Decline profiles. Empirical research suggested that sibling relationships deteriorate during this stressful time, in part because of greater conflicts in parent–adolescent relationships and increased parenting harshness (Kim et al., 2006; Prime et al., 2020). This finding could also be explained by the original spillover theory, which states that the negative aspect of parent–adolescent relationship has a greater influence on adolescents’ relationship quality with others (Liu et al., 2020; Sanders & Morawska, 2018).

The validity of the four relationship profiles identified in current research was bolstered by revealing variation of negative emotional and behavioral responses across the profiles. Further, family relationships influenced adolescents’ emotional and behavioral responses during times of crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, since the interaction between adolescents and family members increased significantly (Prime et al., 2020). As found in empirical studies, warmth and conflicts have been demonstrated to be protective and risk factors for adolescents’ adjustment, respectively (Buist et al., 2013; Shahar & Henrich, 2016). Adolescents with the Cohesive-Decline and Mild-Decline profiles, which were characterized by more relationship warmth and low levels of conflict, displayed lower level of emotional and behavioral responses. Alternatively, adolescents being in the Conflictual-Stable and Indifferent-Stable profiles and experiencing frequent conflicts with low levels of warmth displayed higher level of emotional and behavioral responses. As these findings considered both sides of family relationships and the change of relationship quality after the pandemic, they provide a more comprehensive overview of the links between family relationships and adolescents responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Of the four relationship profiles, adolescents with Conflictual-Stable profiles with the highest level of conflict were more likely to experience emotional and behavioral responses than those with other profiles, even though the degree of warmth in this profile was greater than in the Indifferent-Stable profile. This finding adds evidence to emotional security theory, which states that conflict in relationships has a more substantial influence on adolescents than relationship warmth (Cummings & Miller-Graff, 2015). Frequent conflicts in family causes tense family dynamics, which undermined the protective effect of warmth, arousing the negative emotional and behavioral responses of adolescents (Cook et al., 2009; Sanders & Morawska, 2018). Additionally, regardless of the decline in relationship quality, adolescents with Cohesive-Decline and Mild-Decline profiles were less likely to exhibit emotional and behavioral responses. Consist with this finding, emotional security theory suggests that adolescents with high-quality family relationships are better adjusted (Alegre et al., 2014) and express fewer emotional and behavioral responses to public emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic (Prime et al., 2020). While adolescents with Cohesive-Decline profile reported fewer emotional and behavioral responses at the time of our study, their psychological well-being might be undermined if the pandemic continues. Thus, interventions for these adolescents should place greater emphasis on relationship changes. In sum, these findings suggest that more attention should be given to relationship conflicts, especially for adolescents in Conflictual-Stable families.

These findings reflect the unique cultural characteristics of the sample of Chinese adolescents and families. First, traditional Chinese culture (e.g., Confucian ideology) places a significant emphasis on family values (Fei, 1983), which is deeply ingrained in the population. Under the external stress of public emergencies, Chinese people are more prone to rely on family units (Tang & Li, 2021). This mindset of connecting family members together amplifies the effects of family relationship quality on adolescents’ responses, which may distinguish the results of this study to different populations. Second, the families in this study had a relatively low social economic status (SES), as less than half parents held a high school degree or above, and the majority of families perceived their family income as average. Tang and Li (2021) revealed that lower SES families in China (e.g., migrant families) rely more on family units and support other family members in order to minimize risk. Therefore, the findings should be carefully considered when generalizing to different cultures or high SES families. Studies in diverse cultural contexts are needed to fully understand how public emergencies influence family dynamics and adolescent’s maladaptive responses.

Limitations

The current study has certain limitations. First, all study variables were self-reported by adolescents, potentially leading to common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Future studies should collect multi-source data from all family members to replicate this relationship. Second, data on relationship quality prior to the pandemic were collected retrospectively and, therefore, may be inaccurate. However, at least for the moment, there is no real alternative for measuring relationship quality prior to the pandemic. It is undeniable that adolescents’ retrospective reports may be influenced by current stress during the COVID-19 pandemic (Matt et al., 1992). Third, given the cross-sectional design of this study, it is difficult to establish evidence of a causal relationship. Although the direction assumed here is consistent with past research suggesting an influence of family relationships on adolescents’ negative responses, it is possible that this influence may be reversed (Hatfield et al., 1993) or even reciprocal. Longitudinal studies are necessary to confirm the causal relationships implied by our model. Finally, these findings may be specific to the study’s sample of Chinese adolescents, restricting the generalizability of our results to individuals in other cultures. Future studies should consider more diverse samples from multiple cultures and societies.

Implications

Despite the limitations, this study has the following implications. First, the present research substantiates the theoretical hypothesis that relationships in different families were impacted differently by the COVID-19 pandemic (Brock & Laifer, 2020; Prime et al., 2020). For social workers and clinicians, it should be recognized that adolescents with different relationship profiles need individualized treatment. More emphasis should be placed on the increase of family conflicts among adolescents who previously had high quality of family relationships. While attention should be paid to the lack of family relationship warmth among adolescents with Conflictual-Stable and Indifferent-Stable profiles. Second, our study highlights the primary protective role of close family relationships by revealing how these four relationship patterns are related to adolescents’ emotional and behavioral responses during the pandemic. To enhance adolescents’ coping abilities during emergencies, preventive measures and interventions based on family relationships are recommended. Given the difficulties of accessing face-to-face interventions during lockdowns, parents and adolescents could use online resources to build more cohesive families (Cluver et al., 2020), which may serve as the first place defense against the negative psychological responses brought by the COVID-19. Finally, the link between family relationship patterns and responses contributes to the identification of potentially at-risk groups. Inventions may be more important for adolescents with profiles characterized by stable low warmth and high conflict, as this group was at greater risk for emotional responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adhikari, S. P., Meng, S., Wu, Y. J., Mao, Y. P., Ye, R. X., Wang, Q. Z., Sun, C., Sylvia, S., Rozelle, S., Raat, H., & Zhou, H. (2020). Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: A scoping review. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 9(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x

Ainsworth, M. S., & Bowlby, J. (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. American Psychologist, 46(4), 333–341.

Akaike, H. (1974). A New Look at the Statistical Model Identification. In E. Parzen, K. Tanabe, & G. Kitagawa (Eds.), Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike (pp. 215–222). Springer.

Alegre, A., Benson, M. J., & Pérez-Escoda, N. (2014). Maternal warmth and early adolescents’ internalizing symptoms and externalizing behavior: Mediation via emotional insecurity. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 34(6), 712–735.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling, 21(3), 329–341.

Ayuso, L., Requena, F., Jiménez-Rodriguez, O., & Khamis, N. (2020). The effects of COVID-19 confinement on the Spanish family: Adaptation or change? Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 51(3–4), 274–287.

Babore, A., Lombardi, L., Viceconti, M. L., Pignataro, S., Marino, V., Crudele, M., Candelori, C., Bramanti, S. M., & Trumello, C. (2020). Psychological effects of the COVID-2019 pandemic: Perceived stress and coping strategies among healthcare professionals. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113366

Boer, F., Goedhart, A. W., & Treffers, P. D. A. (1992). Siblings and their parents. In F. Boer & J. Dunn (Eds.), Children’s Sibling Relationships: Developmental and Clinical Issues (pp. 41–54). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Brock, R. L., & Laifer, L. M. (2020). Family science in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: Solutions and new directions. Family Process, 59(3), 1007–1017.

Browne, D. T., Plamondon, A., Prime, H., Puente-Duran, S., & Wade, M. (2015). Cumulative risk and developmental health: An argument for the importance of a family-wide science. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 6(4), 397–407.

Buhrmester, D., & Furman, W. (1990). Perceptions of sibling relationships during middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development, 61(5), 1387–1398.

Buist, K. L., & Vermande, M. (2014). Sibling relationship patterns and their associations with child competence and problem behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(4), 529–537.

Buist, K. L., Deković, M., & Prinzie, P. (2013). Sibling relationship quality and psychopathology of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 97–106.

Chen, B., Sun, J., & Feng, Y. (2020). How have COVID-19 isolation policies affected young people’s mental health?–Evidence from Chinese college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1529.

Cluver, L., Lachman, J. M., Sherr, L., Wessels, I., Krug, E., Rakotomalala, S., Blight, S., Hillis, S., Bachman, G., & Green, O. (2020). Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet, 395(10231):e64. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01529

Cook, J. C., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Buckley, C. K., & Davis, E. F. (2009). Are some children harder to coparent than others? Children’s negative emotionality and coparenting relationship quality. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(4), 606–610.

Cooper, K., Hards, E., Moltrecht, B., Reynolds, S., Shum, A., McElroy, E., & Loades, M. (2021). Loneliness, social relationships, and mental health in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 289, 98–104.

Cummings, E. M., & Miller-Graff, L. E. (2015). Emotional security theory: An emerging theoretical model for youths’ psychological and physiological responses across multiple developmental contexts. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(3), 208–213.

Cummings, E. M., Davies, P. T., & Campbell, S. B. (2020). Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. Guilford Publications.

Davies, P. T., Parry, L. Q., Bascoe, S. M., Martin, M. J., & Cummings, E. M. (2019). Children’s vulnerability to interparental conflict: The protective role of sibling relationship quality. Child Development, 90(6), 2118–2134.

Denissen, J. J. A., van Aken, M. A. G., & Dubas, J. S. (2009). It takes two to tango: How parents’ and adolescents’ personalities link to the quality of their mutual relationship. Developmental Psychology, 45(4), 928–941.

Fei, X. (1983). Problem of providing for the senile in the changing family structure. Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 3, 6–15.

Feinberg, M. E., McHale, S. M., Crouter, A. C., & Cumsille, P. (2003). Sibling differentiation: Sibling and parent relationship trajectories in adolescence. Child Development, 74(5), 1261–1274.

Geiser, C. (2012). Data analysis with Mplus. Guilford press.

Hakvoort, E. M., Bos, H. M. W., van Balen, F., & Hermanns, J. M. A. (2010). Family relationships and the psychosocial adjustment of school-aged children in intact families. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 171(2), 182–201.

Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Rapson, R. L. (1993). Emotional Contagion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2(3), 96–100.

Jenkins, J., Rasbash, J., Leckie, G., Gass, K., & Dunn, J. (2012). The role of maternal factors in sibling relationship quality: A multilevel study of multiple dyads per family. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(6), 622–629.

Kenny, R., Dooley, B., & Fitzgerald, A. (2013). Interpersonal relationships and emotional distress in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 36(2), 351–360.

Kim, J. Y., McHale, S. M., Wayne Osgood, D., & Crouter, A. C. (2006). Longitudinal course and family correlates of sibling relationships from childhood through adolescence. Child Development, 77(6), 1746–1761.

Kretschmer, T., & Pike, A. (2009). Young children’s sibling relationship quality: Distal and proximal correlates. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(5), 581–589.

Lee, J., Lim, H., Allen, J., & Choi, G. (2021). Multiple mediating effects of conflicts with parents and self-esteem on the relationship between economic status and depression among middle school students since COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 3128.

Lindgaard, C. V., Iglebaek, T., & Jensen, T. K. (2009). Changes in family functioning in the aftermath of a natural disaster: The 2004 tsunami in Southeast Asia. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14(2), 101–116.

Liu, L., He, X., Li, C., Xu, L., & Li, Y. (2020). Linking parent–child relationship to peer relationship based on the parent-peer relationship spillover theory: Evidence from China. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105200.

Matt, G. E., Vázquez, C., & Campbell, W. K. (1992). Mood-congruent recall of affectively toned stimuli: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 12(2), 227–255.

McLachlan, G. J., Lee, S. X., & Rathnayake, S. I. (2019). Finite mixture models. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application, 6, 355–378.

Miller, I. W., Ryan, C. E., Keitner, G. I., Bishop, D. S., & Epstein, N. B. (2000). The McMaster approach to families: Theory, assessment, treatment and research. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 168–189.

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569.

Özaslan, A., Yıldırım, M., Güney, E., Güzel, H. Ş., & İşeri, E. (2022). Association between problematic internet use, quality of parent-adolescents relationship, conflicts, and mental health problems. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(4), 2503–2519.

Pan, A., Liu, L., Wang, C., Guo, H., Hao, X., Wang, Q., Huang, J., He, N., Yu, H., Lin, X., Wei, S., & Wu, T. (2020). Association of Public health interventions with the epidemiology of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. JAMA, 323(19), 1915.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569.

Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643.

Rains, L. S., Johnson, S., Barnett, P., Steare, T., Needle, J. J., Carr, S., Taylor, B. L., Bentivegna, F., Edbrooke-Childs, J., & Scott, H. R. (2021). Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care and on people with mental health conditions: Framework synthesis of international experiences and responses. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(1), 13–24.

Raudino, A., Fergusson, D. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2013). The quality of parent/child relationships in adolescence is associated with poor adult psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Adolescence, 36(2), 331–340.

Sanders, R. (2004). Sibling relationships: Theory and issues for practice. Macmillan International Higher Education.

Sanders, M. R., & Morawska, A. (Eds.). (2018). Handbook of Parenting and Child Development across the Lifespan. Springer.

Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464.

Sclove, S. L. (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52(3), 333–343.

Sevilla, A., & Smith, S. (2020). Baby steps: The gender division of childcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36, S169–S186.

Shahar, G., & Henrich, C. C. (2016). Perceived family social support buffers against the effects of exposure to rocket attacks on adolescent depression, aggression, and severe violence. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(1), 163–168.

Shen, J., Sun, R., Xu, J., Dai, Y., Li, W., Liu, H., & Fang, X. (2021). Patterns and predictors of adolescent life change during the COVID-19 pandemic: a person-centered approach. Current Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02204-6

Sinko, L., He, Y., Kishton, R., Ortiz, R., Jacobs, L., & Fingerman, M. (2022). “The stay at home order is causing things to get heated up”: Family conflict dynamics during COVID-19 from the perspectives of youth calling a national child abuse hotline. Journal of Family Violence, 37(5), 837–846.

Solmeyer, A. R., & Feinberg, M. E. (2011). Mother and father adjustment during early parenthood: The roles of infant temperament and coparenting relationship quality. Infant Behavior and Development, 34(4), 504–514.

Sturge-Apple, M. L., Davies, P. T., Cicchetti, D., & Fittoria, M. G. (2014). A typology of interpartner conflict and maternal parenting practices in high-risk families: Examining spillover and compensatory models and implications for child adjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 26(4pt1), 983–998.

Su, B., Yu, C., Zhang, W., Su, Q., Zhu, J., & Jiang, Y. (2018). Father–child longitudinal relationship: Parental monitoring and Internet Gaming Disorder in Chinese adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 95.

Tang, S., & Li, X. (2021). Responding to the pandemic as a family unit: Social impacts of COVID-19 on rural migrants in China and their coping strategies. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 1–11.

Van Petegem, S., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Beyers, W. (2015). Rebels with a cause? Adolescent defiance from the perspective of reactance theory and self-determination theory. Child Development, 86(3), 903–918.

Walsh, F. (2016). Family resilience: A developmental systems framework. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(3), 313–324.

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729

Wang, M. T., Henry, D. A., Del Toro, J., Scanlon, C. L., & Schall, J. D. (2021). COVID-19 Employment Status, Dyadic Family Relationships, and Child Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(5), 705–712.

Whiteman, S. D., McHale, S. M., & Soli, A. (2011). Theoretical perspectives on sibling relationships. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 3(2), 124–139.

Williams, A. L., & Merten, M. J. (2011). iFamily: Internet and social media technology in the family context. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 40(2), 150–170.

Woods, J. A., Hutchinson, N. T., Powers, S. K., Roberts, W. O., Gomez-Cabrera, M. C., Radak, Z., Berkes, I., Boros, A., Boldogh, I., & Leeuwenburgh, C. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and physical activity. Sports Medicine and Health Science, 2(2), 55–64.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). WHO director-general's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-−11-march-2020/

Xia, M., Weymouth, B. B., Bray, B. C., Lippold, M. A., Feinberg, M. E., & Fosco, G. M. (2020). Exploring triadic family relationship profiles and their implications for adolescents’ early substance initiation. Prevention Science, 21(4), 519–529.

Acknowledgements

The study described in this report was supported by Mental Health Programme for COVID-19 pandemic by Beijing Normal University Faculty of Psychology and Education Foundation, National Nature Science Foundation of China (31800935), the COVID-19 Prevention and Research Emergency Project of Beijing Normal University, and the COVID-19 Mental Health Support Project of the Faculty of Psychology of Beijing Normal University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We are appreciative of the participants in our study and the many people who offered kind assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yingying Tang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Xiuyun Lin: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. Yingmiao Shao: Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. Ting He: Investigation, Writing—review & editing. Yulong Wang: Review & editing. Stephen P. Hinshaw: Review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Prior to conducting the study, the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Normal University in China approved the research protocol, including the consent procedure. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A

Appendix A

Table 5

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Y., Shao, Y., He, T. et al. Latent profiles of adolescents’ relationships with parents and siblings: Associations with emotional and behavioral responses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol 42, 31079–31090 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03959-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03959-2