Abstract

As a necessary means of encouraging individuals to adopt healthy behaviors, improving the persuasiveness of ads related to health has been a major topic of common concern in both academic and practical circles. However, scant attention has been given to how consumers’ fresh start mindset (FSM) may influence the effect of ad types on health persuasion. Based on the construal level theory (CLT), the current research investigates the interplay of ad type (progression ad vs. before/after ad) and FSM (weak vs. strong) on the persuasiveness of health ads and the mechanisms underlying it. Across three studies, we demonstrated that progression ads are more effective when consumers have a weak FSM, whereas a before/after ad will be more persuasive when consumers hold a strong FSM. More importantly, consumers’ perceived feasibility and desirability drive the interactive effect of ad type and FSM, such that perceived feasibility mediates the positive effect of progression ads on persuasion among consumers with a weaker FSM, while perceived desirability mediates the positive effect of before/after ads on persuasion among consumers with a stronger FSM. Our findings extend the existing literature streams on the fresh start effect, message persuasion, and construal level theory and provide practical insights for health product manufacturers and policymakers concerned about public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the improvement of living standards, health problems have become a common concern for many consumers. As a way to appeal to consumers to adopt healthy behaviors and improve their health conditions, health ads form an omnipresent part of our daily lives (Han et al., 2016; Kergoat et al., 2019; Meyer et al., 2020; Rimer & Kreuter, 2006). Given this backdrop, understanding how to achieve the effectiveness of health ads is of importance. To vividly show product efficacy, marketers attempt to exhibit the change that products bring. A change ad, which is widely used in the marketplace, is defined as an ad that shows the corresponding changes delivered by a health product (or service). A change ad can be classified as either a progression ad or a before/after ad (Cian et al., 2020). For instance, when highlighting the changes that occur after orthodontic treatment, a progression ad will present the state of the teeth that range from irregular (before) to slightly aligned (intermediate) and finally to perfectly aligned (after), while a before/after ad will only compare irregularly aligned teeth (before) with perfectly aligned teeth (after). Other health persuasions (e.g., weight-loss programs, acne treatments, hair-growth treatments, and teeth-whitening products) could be also promoted through change ads to emphasize product efficacy.

Recent research has documented that compared with before/after ads, progression ads are more likely to encourage consumers to engage in process simulation spontaneously and therefore make the ads more credible and persuasive (Cian et al., 2020). However, a particular type of ad cannot be effective in all cases. When designing an advertising campaign, it is of importance to take the characteristics of the ad and its receivers (i.e., the targeted consumers) into consideration. Previous research demonstrated that the content, message frame, and presentation of ads influence different consumers’ adoption and purchase behaviors (Chen et al., 2019; Han et al., 2016; Meyer et al., 2020). Therefore, it is more likely to enhance the persuasiveness and effectiveness of health appeals by choosing the type of ads that is matched with consumers’ characteristics. The idea that individuals can create a new beginning, known as the fresh start mindset (FSM), represents one of consumers’ characteristics (Milfeld et al., 2021; Price et al., 2018; Strizhakova et al., 2021). We identify a conditional boundary of FSM on the effectiveness of progression and before/after ads in the health persuasion context.

Both progression and before/after ads are designed to highlight a desired change which to achieve one must start to engage in the transformation process at some point. Since FSM reflects an individual difference in the belief that individuals can make a new start regardless of their past or present circumstances (Chen et al., 2020; Price et al., 2018), the current research aims to investigate the effect of ad type (i.e., progression ad vs. before/after ad) on health persuasion and the underlying mechanisms from the perspective of a fresh start mindset. This research revealed that health ads are more persuasive when their type is matched with the level of consumers’ FSM. In addition, perceived feasibility and desirability play mediating roles in the matching effect. Specifically, when consumers hold a strong FSM, perceived desirability mediates the positive effect of before/after ad on persuasion, whereas when consumers hold a weak FSM, perceived feasibility mediates the positive effect of progression ad on persuasion.

Our work makes theoretical contributions to the persuasion literature by introducing the fresh start mindset to the context of health persuasion and investigating its effects in influencing the effectiveness of different types of change ads (Kidwell et al., 2013; Winterich et al., 2012). The present research also extends the literature on the FSM and its downstream effects (Dai et al., 2014; Price et al., 2018). In addition, to reveal the underlying processes of the interactive effect of ad type and FSM on persuasion, this research examined the mediating effects of feasibility and desirability, which contributes to the research on construal level theory (Hsieh & Yalch, 2020; Lu et al., 2013).

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Change ads and fresh start mindset

Change ads refer to advertisements that highlight the changes or transformations delivered by the promoted products or services (Cian et al., 2020; Kirmani & Wright, 1989). Visual cues such as pictures or text are often used by marketers and advertisers to help consumers process the advertised information and further influence their judgments and decision-making (Wang et al., 2017). When using visual cues to depict changes, two types of change ads are applied in the marketplace: progression ads that visualize the initial state, the intermediate outcome(s), and the final result of the changing process, along with the before/after ads that only show the initial state and final result of the change. The major difference between these two ad types is that the former presents the change gradually, while the latter depicts the change immediately. Prior research has suggested that consumers who have not previously experienced the advertised health service (e.g., weight-loss program) or product (e.g., spot-removing product) anticipate the effectiveness of the service or product by mentally simulating the process of engaging in the service or interacting with the product (Schlosser, 2003). Based on this finding, Cian et al. (2020) demonstrated that compared with a before/after ad, a progression ad that presents the intermediate outcomes of the change step by step is more likely to facilitate consumers to engage in a real-life simulation of the change process and therefore increases the credibility and persuasiveness of the change ad.

However, no ad can be effective under all circumstances. It is notable that the type of ad utilized should be decided according to the characteristics of its target consumers (Rimer & Kreuter, 2006). Existing research has documented that an ad would be more persuasive when its type matches receivers’ mindsets and cognitive or affective states (Cesario et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2021; Han et al., 2016; Kidwell et al., 2013). Given that consumers wish to achieve the final result as advertised and more or less want to start to change when viewing the ad, this study introduces the construct “fresh start mindset” to examine the effectiveness of different ad types in health persuasion (Strizhakova et al., 2021). That is, when designing a persuasive change ad (progression vs. before/after), consumers’ FSM should be taken into consideration. Specifically, fresh start mindset refers to “a belief that people can make a new start, get a new beginning, and chart a new course in life, regardless of their past or present circumstances” (Price et al., 2018, p. 22). It is not only a chronic individual difference (i.e., trait FSM) but also a situational factor (i.e., state FSM) that can be primed with context cues such as pictures or text (Chen et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2013; Price et al., 2018; Strizhakova et al., 2021). A fresh start often implies a beginning point of a transformation and can be symbolized either by a temporal landmark (e.g., the New Year) or a minimal change in the status quo (Bi et al., 2021; Crockett et al., 2013; Dai et al., 2014). Although the fresh start mindset reflects both the belief in self-transformation (e.g., start to work hard from the New Year) and the positive attitude toward others’ transformations (e.g., supporting wrongdoers to begin anew), the present research mainly focuses on the former due to the context of health ads.

Perceived feasibility and desirability

Construal level theory (CLT) proposes that individuals’ representations of an event or object are affected by the psychological distance between themselves and the event or object: when the psychological distance is proximal, the construal level is low, and individuals tend to make concrete, detailed, and contextualized representations of the target, whereas when the psychological distance is greater, the construal level will be high, and individuals are more likely to represent the event or object in a more abstract, global and decontextualized way (Trope & Liberman, 2010). Extensive empirical studies from the marketing and advertising fields confirmed that the construal level significantly impacts consumer attitude, judgment, evaluation, and decision-making (Han et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2019; Reczek et al., 2018).

Based on construal level theory, desirability reflects the valence of an event’s (e.g., lose weight) end state, while feasibility refers to the difficulty of reaching this end state. That is, a desirability consideration focuses more on the ends, whereas a feasibility consideration emphasizes more on the means (Liberman & Trope, 1998). Therefore, when considering the desirability of a health behavior (e.g., losing weight), consumers rely more on abstract and holistic information (e.g., losing weight makes the figure look better) to represent this behavior, while when considering the feasibility of losing weight, consumers tend to emphasize the concrete and local information (e.g., means of losing weight) of the behavior (Han et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2019; Reczek et al., 2018). Previous research on mental simulation has suggested that desirability is more reason-oriented and focuses on the “WHY” matter, whereas feasibility is more action-oriented and emphasizes the “HOW” matter (Zhao et al., 2011). For example, when consumers see a health ad about teeth whitening, high desirability means that they focus more on why they need to whiten their teeth, whereas high feasibility encourages them to consider more about how to whiten their teeth. Consumers’ evaluations of products or services are highly influenced by these two aspects. Therefore, ads that can enhance consumers’ perceived desirability and feasibility would be more persuasive (Han et al., 2019; Hsieh & Yalch, 2020; Strizhakova et al., 2021).

The persuasiveness of progression versus before/after ads under different levels of FSM

As mentioned previously, extensive research has demonstrated that ads whose type matches consumers’ characteristics would be more persuasive. For instance, Han and his colleagues (2016) documented that low-construal-level (high-construal-level) messages in ads are more persuasive for consumers primed with problem-focused (emotion-focused) strategies. Kidwell et al. (2013) demonstrated that liberals (conservatives) are more persuaded by an individualizing (binding) ad. In line with this stream of literature, the current research suggests that matching the types of change ads (i.e., progression vs. before/after) with consumers’ FSM will enhance health persuasion.

Prior work has demonstrated that individuals with a stronger FSM tend to get a new beginning and say goodbye to the past; thus, they are more future-oriented, whereas those with a weaker FSM believe less about their ability to make a new start and have fewer expectations about the future; therefore, they are more present-oriented (Chen et al., 2019, 2020). Therefore, when viewing a change ad of a health product or service, consumers with a weaker FSM would perceive the temporal distance to the change as more proximal and tend to focus on the concrete features and messages of the ad, and thus, perceive higher feasibility of the change. Meanwhile, progression ads that show the step-by-step effects of health products (or services) can foster consumers’ process simulations of the steps to achieve the changes (Zhao et al., 2011). These ads can increase the feasibility of the change by helping consumers consider the intermediate steps to the end (Han et al., 2019). That is, consumers might find the product efficacy that these ads advocate more feasible. When consumers hold a weak FSM, they are more likely to focus on the near events rather than events that might happen in the future (Price et al., 2018). Accordingly, we propose that progression ads (vs. before/after ads) are more matched with a weaker FSM, and this match will increase consumers’ perceived feasibility of the advertised changes (Cian et al., 2020). Therefore, consumers with a weaker FSM would be more persuaded by progression ads.

On the other hand, consumers with a stronger FSM would perceive the temporal distance to the advertised change as more distant and tend to focus on the abstract features and messages of the ad (Han et al., 2019) and further perceive higher desirability of the change (Chen et al., 2019; Hsieh & Yalch, 2020). Before/after ads that only present the contrasts between the start and end states of using health products or services can trigger consumers’ simulations of the desirable outcomes, which are usually the reasons and incentives for consumers to purchase the advertised products (Han et al., 2019; Hsieh & Yalch, 2020; Lu et al., 2013). Therefore, these ads can increase the desirability of the changes by encouraging consumers to focus on why they need to use the products or services and the benefits they obtain (Hsieh & Yalch, 2020; Liu, 2008). Consequently, we propose that before/after ads (vs. progression) are more matched with a stronger FSM, and this match will increase consumers’ perceived desirability of the advertised changes (Lu et al., 2013). Therefore, consumers with stronger FSM would be more persuaded by before/after ads. Stated formally,

Hypothesis 1

The interaction between ad type and FSM has a significant impact on health persuasion. Specifically, (a) progression ads are more persuasive for consumers with a weaker FSM, and (b) before/after ads are more persuasive for consumers with a stronger FSM.

Hypothesis 2

Perceived feasibility and desirability mediate the interaction of ad type and FSM on health persuasion. Specifically, (a) perceived feasibility mediates the positive effect of progression ads on persuasion among consumers with a weaker FSM, and (b) perceived desirability mediates the positive effect of before/after ads on persuasion among consumers with a stronger FSM.

Study 1

The objective of Study 1 is to test the interactive effect of ad type and fresh start mindset on persuasion. A 2 (ad type: progression vs. before/after) × 2 (FSM: weak vs. strong) between-subjects design was conducted in this study. The public-concerned issue, teeth whitening, was chosen as the experimental context. We expect that participants primed with a weak FSM will be more persuaded by a progression ad, while a before/after ad will be more persuasive for those primed with a strong FSM.

Stimuli

According to the research conducted by Cian et al. (2020), we designed the health ads of a fictitious teeth-whitening product called UYA (see Appendix A). In particular, the before/after ad presented two images of a person’s teeth, yellower in the “before” image and whiter in the “after” image. The progression ad, however, not only showed the same “before” and “after” images but also presented an additional image of an “intermediate” outcome. Other elements of these two ads such as the typography, fonts, and messages were consistent. Following Chen et al. (2020), FSM was primed through a reading task. In the weak FSM condition, participants read an article as follows: The road of life is long but lacks opportunities for a fresh start. On the road of life, no matter how we want to, we can hardly make a new start and turn over a new leaf. For instance, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Database, four hundred thousand prisoners are released each year. Then, two-thirds of them would be arrested again in three years, and three-quarters of them would be arrested again in five years. It is difficult for the released prisoners to get a fresh start. Their lives are haunted by past mistakes, people who have stayed away because of their past, and the lack of love, friends, and guidance. Therefore, they are very likely to be stuck in trouble again. For them, getting out of prison doesn’t mean a fresh start, instead, it’s about the continuation of the past. That is, it’s hard for them to erase their past mistakes and start anew in their lives. In the strong FSM condition, participants read an article as follows: The road of life is long and full of opportunities for a fresh start. As long as we are willing to, we can always make a new start and turn over a new leaf on the road of life. Jordan was a young man with a history of violence, drunk and disorderly, he was even arrested and imprisoned seven years ago for attempted robbery. During the reform-through-labor, he learned many cooking skills and was given an early release. Since then, he re-examined his life and decided to behave well. One month later, he ran into Pat, his high school classmate, and got a job as a restaurant chef from him. Jordan was excited about his fresh start and started to work and live hard since then. Now, Jordan has not only become a senior chef but also has his own chain of restaurants, which makes his career flourish.

In an independent pretest (n = 50), the effectiveness of this manipulation was tested. After reading one of the two articles about fresh starts, participants were asked to indicate their beliefs about fresh starts on a 5-item scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree; Price et al. 2018; α = 0.87). The results revealed that participants in the strong FSM condition were more likely to believe that people can make a new start than those in the weak FSM condition (Mstrong FSM = 4.93, SD = 1.31; Mweak FSM = 4.08, SD = 1.10; t (1, 48) = -2.487, p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.70), confirming the effectiveness of FSM manipulation.

Procedure

One hundred ninety-two participants (52.6% male, Mage = 20.75, SD = 2.41) were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions (progression ad – weak FSM, progression ad – strong FSM, before/after ad – weak FSM, before/after ad – strong FSM) and signed the consent form prior to the study. They were first informed that this study included 2 seemingly unrelated tasks: a reading task followed by a marketing survey on a health product. First, participants were asked to read one of the two articles about fresh starts as described above. To ensure that they could fully understand the meaning of the articles, participants were allotted a reading time of no less than 2 min. To mask the objective of this study, participants were told that we were interested in their immediate memory so were encouraged to recall and write down excerpts from the article. Then, participants viewed one of the two UYA teeth-whitening powder ads and indicated their attitudes to the ad on three 7-point items (e.g., “To what extent do you like this teeth-whitening powder?”; 1 = not at all, 7 = very much; α = 0.78; Mayer & Tormala 2010). Upon finishing the focal tasks, participants completed a simple arithmetic problem that served as an attention check and answered the manipulation check items of FSM (Price et al. 2018; α = 0.72). Next, participants indicated their mood state on three 7-point positive affect items (“active/excited/enthusiastic”, α = 0.84) and three 7-point negative affect items (“distress/nervous/upset”, α = 0.71; Watson et al., 1988) and answered another three 7-point items that measured their perceived informativeness and visual complexity of the ad and the importance of teeth whitening to them (Cian et al. 2020; Kidwell et al. 2013). Finally, they responded to demographic questions and were compensated for their participation.

Results

A manipulation check showed that participants in the strong FSM (vs. weak FSM) condition were more likely to agree that people have a chance to make a new start (Mhigh FSM = 4.47, SD = 0.86; Mlow FSM = 3.85, SD = 0.88; F (1, 188) = 27.24, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.127), while the effects of ad type (F (1, 188) = 0.81, p > 0.10) and its interaction with the manipulation of FSM (F (1, 188) = 0.51, p > 0.10) were not significant, indicating that the manipulation of FSM was successful.

A 2 (ad type: progression vs. before/after) × 2 (FSM: weak vs. strong) between-subjects ANOVA with advertising attitude as the dependent variable revealed a significant main effect of FSM (F (1, 188) = 5.54, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.029). The results showed that participants in the strong FSM (vs. weak FSM) condition had more positive attitudes towards the health ad (Mstrong FSM = 4.52, SD = 1.32; Mweak FSM = 4.10, SD = 1.16). The main effect of ad type, however, was nonsignificant (F (1, 188) = 1.81, p > 0.10). More importantly, the expected interaction of ad type and FSM on advertising attitude was significant (F (1, 188) = 38.89, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.171). As shown in Fig. 1, post hoc contrasts revealed that participants in the weak FSM condition indicated a more positive attitude toward the progression ad (M = 4.42, SD = 1.17) than to the before/after ad (M = 3.60, SD = 0.98; F (1, 188) = 12.04, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.119), whereas those in the strong FSM condition showed a more positive attitude to the before/after ad (M = 5.05, SD = 0.93) than to the progression ad (M = 3.76, SD = 1.34; F (1, 188) = 29.05, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.227). In addition, when participants’ mood, the informativeness and visual complexity of the ads, and the importance of teeth whitening were included in the model as covariates, the interactive effect of ad type and FSM on ad attitude remained significant (p < 0.05), indicating that these variables did not account for the confirmed effect.

Discussion

Study 1 investigated how the type of health ad and consumers’ FSM jointly influenced ad persuasiveness. The results showed that for consumers with a weak FSM, a progression ad would be more persuasive, whereas for those with a strong FSM, a before/after ad would be more persuasive, thus supporting Hypothesis 1. This study also ruled out several alternative explanations that participants’ mood state, the informativeness and visual complexity of the ads, and participants’ perceived importance of teeth whitening may account for the observed results. However, there are still several problems that need further consideration. First, the progression ad in Study 1 only presented three images, but four, five, or even more images are used in marketing practice to show the gradual changes caused by a health product or service. Whether the number of images used in progression ad will influence our core effect needs further investigation. Second, FSM was manipulated through a reading task in this study, and it is worthwhile to explore whether individuals’ trait FSM rather than state FSM will have the same effect on health persuasion. Third, participants’ attitudes toward the health ad were measured in a self-reported manner, which may lead to some bias in the final results. Therefore, measures that can capture participants’ interest in the products (e.g., actively learning more about the products) are needed. In addition, whether consumers’ needs for a health product affect the findings remained under-covered in Study 1. Study 2 will solve these problems and reveal the underlying processes through which a match between ad type and FSM affects persuasion.

Study 2

Study 2 aims to replicate the findings in Study 1 and more importantly, test the mediating roles of perceived feasibility and desirability in the interactive effect of ad type and FSM on persuasion (H2). This study utilized a 2 (ad type: progression vs. before/after) × 2 (FSM: weak vs. strong) between-subjects design, with the ad type as a manipulated factor and FSM as a measured factor. Hair restorers were chosen as the focal product in this study since an increasing number of people are concerned with hair loss problems. We expect that a match between a weak FSM and progression ad increases advertising persuasiveness via perceived feasibility, whereas a match between a strong FSM and before/after ad enhances advertising persuasiveness via perceived desirability.

Stimuli

The ads of the hair restorer were designed as in Study 1 (see Appendix B). Specifically, the before/after ad featured two photos of a woman, whose hair is thinner in the “before” image and thicker in the “after” image. The progression ad featured the same “before” and “after” photos and three additional intermediate outcomes that show the process during which the hair grows. The other elements of the two ads are identical. In contrast to Study 1, participants were asked to finish the study on their mobile phones rather than on a computer screen to better reflect consumers’ real shopping experiences (Wang et al., 2015). A QR code were also presented in which participants could obtain more information about the hair restorer through scanning it.

Procedure

One hundred and seventy-five participants (41.7% males, Mage = 31.27, SD = 6.10) were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions (progression ad, before/after ad). At the beginning of the experiment, participants responded to a screening question that asked, “Are you suffering from thinning hair or hair loss problems?” Only those who answered “Yes” were allowed to move to follow-up tasks. After answering demographic questions and providing their social media accounts, participants finished five 7-point items of FSM (e.g., “Anyone can make a new start if they want to”; 1 = strongly agree, 7 = strongly disagree; α = 0.72; Price et al., 2018). Next, participants were informed that a brand intends to launch a new hair restorer and wants to collect the opinions of their target consumers. Then, participants were asked to choose the flavor they liked for the product from several options, such as ginger flavor, herb flavor, lemon flavor, etc. This question was designed to conceal the purpose of the study. Afterward, participants viewed one of the two ads of the hair restorer and responded to questions about the perceived feasibility and desirability of the change (i.e., hair restoration). Specifically, participants indicated to what extent they agreed with the following statements: (1) the restoration of hair is achievable; (2) the restoration of hair is of great value to me (1 = not at all, 7 = very much; Han et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2013). Considering that many consumers may worry about the possible adverse influence of using the product, we also measured participants’ prior knowledge about and perceived risk of the hair restorer (Wang et al., 2017). Finally, participants saw a QR code and an instruction that said if they were interested in the hair restorer, they could scan the QR code to learn more about this product; otherwise, they could click the “quit” button to end the survey. Notably, participants who scanned the QR code were asked to write down their social media accounts for data recording.

Results

We used the number of participants who scanned the QR code as a measure of persuasion. To analyze the data, the QR code scanning behavior was coded as a dummy variable (0 = no scan, 1 = scan), and the FSM was standardized as it is a continuous variable. A logistic regression with ad type, standardized FSM and their interaction as independent variables, and the QR code scanning behavior as the dependent variable revealed that the main effect of FSM was significant (β = -1.31, SE = 0.41, Wald = 10.11, p < 0.01, OR = 0.27), while the main effect of ad type was insignificant (p > 0.10). More importantly, their interplay had a significant impact on participants’ QR code scanning behaviors (β = 0.75, SE = 0.25, Wald = 8.87, p < 0.01, OR = 2.12). As illustrated in Fig. 2, simple slopes analysis showed that when the FSM was weak (M – 1SD), participants were more likely to scan the QR code after they viewed a progression ad than a before/after ad (β = -0.58, SE = 0.45, z =-1.27, p < 0.05), whereas when the FSM was strong (M + 1SD), participants were more likely to scan the QR code after they saw a before/after ad than a progression ad (β = 1.39, SE = 0.46, z = 3.03, p < 0.01).

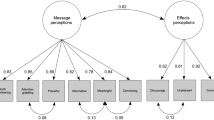

Furthermore, we ran a moderated mediation model using a bootstrapping procedure (PROCESS Model 8, 5000 samples; Hayes 2013) to test the mediating roles of perceived feasibility and desirability. Regarding perceived feasibility, the results indicated that in the weak FSM condition, the mediation effect was significant (indirect effect = -0.27. SE = 0.16; 95% CI = [-0.6267, -0.0053]), whereas in the strong FSM condition, the mediation effect was not significant (indirect effect = 0.04, SE = 0.09; 95% CI = [-0.1281, 0.2505]), supporting that perceived feasibility mediated the effect of ad type on persuasion only in the weak FSM condition. Regarding perceived desirability, the results revealed that in the strong FSM condition, the mediation effect was significant (indirect effect = 0.25, SE = 0.14; 95% CI = [0.0276, 0.6004]), while in the weak FSM condition, the mediation effect was insignificant (indirect effect = -0.03, SE = 0.10; 95% CI [-0.2521, 0.1589]), supporting that perceived desirability mediated the effect of ad type on persuasion only in the strong FSM condition. Taken together, the results of Study 2 provided empirical evidence that supports Hypothesis 2.

In addition, including prior knowledge and perceived risk of the product in the model as covariates did not influence the significant interactive effect of ad type and FSM on persuasion (β = 0.74, SE = 0.25, z = 2.96, p < 0.05), and the effects of prior knowledge and perceived risk on QR code scanning behavior did not reach significance (p > 0.10). Therefore, their potential influence on our core effect was eliminated.

Discussion

The findings of Study 2 revealed the underlying mechanisms of the proposed matching effects by investigating the mediating roles of perceived feasibility and desirability in ad persuasion. As predicted, a match between weak FSM and progression ad influences persuasion via perceived feasibility, whereas a match between strong FSM and before/after ad influences persuasion via perceived desirability. In addition, Study 2 replicated the findings of Study 1 in a new advertising context by measuring participants’ real behaviors (i.e., QR code scanning), which further supported Hypothesis 1. However, there are still some limitations in this experiment. First, the advertised products in Studies 1 and 2 did not require consumers to make an effort, but many health ads need consumers to do so (e.g., lose weight). Therefore, the following study tests our proposed effects in a weight-loss context. Second, FSM was primed using a reading task in Study 1 and measured in Study 2. It is worth investigating whether it can be triggered by the messages in an ad and exert similar impacts on the persuasiveness of different ads. In addition, the visuals used in the first two studies were almost the same (e.g., the same gesture and angle of the woman in the hair restorer ad), but in real life, people did not necessarily take pictures in the same way. To better reflect the real situation, the weight-loss ads in Study 3 showed photos of a woman wearing different clothing in different stages. Finally, previous research has suggested that the underlying mechanisms can be further verified by directly manipulating the mediator variable (Han et al., 2016; Spencer et al., 2005). Therefore, we tested the proposed mediation effects using a moderation approach in Study 3, providing the robust nature of our findings from Studies 1 and 2.

Study 3

Study 3 further tested the underlying mechanisms of the interactive effect of ad type and FSM on persuasion by directly manipulating the perceived feasibility and desirability of participants. In a weight-loss setting, a 2 (ad type: progression vs. before/after) × 2 (FSM: weak vs. strong) × 2 (appeal type: feasibility vs. desirability) between-subjects design was conducted in this study. We expect that when the ad appeal emphasizes the feasibility of the weight-loss program, consumers with weak FSM will be more persuaded by a progression ad; when the ad appeal emphasizes the desirability of the program, consumers will be more persuaded by a before/after ad.

Stimuli

The ads of a weight-loss program were the same as those used in the second study of Cian et al. (2020): the before/after ad featured two photos of a woman’s “before” and “after” status of the weight-loss program, and the progression ad contained another four visuals showing the intermediate status during the program. Different from Study 2, the clothes of the woman in this study varied over time to reflect the real feedback in marketing practice (see Appendix C). According to Price et al. (2018), FSM was triggered through an image showing the rising sun along with the slogan: “Become new self from now on.” Participants in the strong FSM condition viewed this image, while those in the weak FSM condition did not see it at all. An independent pretest (n = 37) showed that compared with participants in the weak FSM condition, those in the strong FSM condition were more likely to believe that people can make a new start (Mstrong FSM = 4.86, SD = 1.17; Mweak FSM = 3.63, SD = 1.34; t (1, 35) = -3.05, p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 1.03). To manipulate the feasibility and desirability of the weight-loss program, we followed the procedure of Han et al. (2019). Specifically, the feasibility appeal included text such as “How do you lose weight? Start by setting a realistic plan, making your daily schedule, maintaining regular exercise, and counting the calories after each workout, etc. You can think of more ways to lose weight.” The desirability appeal included text such as “Why should you lose weight? To wear nice clothes, get compliments from friends, take pretty photos, boost your self-confidence, etc. You can think of more reasons to lose weight.” The results of another independent pretest (n = 40) revealed that participants in the feasibility condition were more likely to agree that the message mainly conveyed how to lose weight (Mfeasibility = 5.36, SD = 1.22; Mdesirability = 3.72, SD = 1.31; t (1, 38) = 4.09, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.32), whereas those in the desirability condition perceived the message as conveying more about why to lose weight (Mfeasibility = 4.50, SD = 1.37; Mdesirability = 5.72, SD = 1.13; t(1, 38) = -3.03, p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.98).

Procedure

Considering that the character of the ad is a woman, 322 female participants (Mage = 22.52, SD = 3.61) were randomly assigned to one of the eight conditions. In this study, participants were asked to assume that they were a slimming consumer and were told that the Bondi Fitness Club (a virtual brand) recently launched a weight-loss program and wanted to know consumers’ attitudes toward it. Then, participants viewed the ad of the weight-loss program (progression vs. before/after) and read the relevant health appeal (feasibility vs. desirability). Next, participants in the strong FSM condition viewed the image of the rising sun, while those in the weak FSM condition did not see anything in this section. Afterward, participants answered an arithmetic problem designed as an attention check and finished the manipulation check items of feasibility (“The message of the ad mainly conveyed how to lose weight”), desirability (“The message of the ad mainly conveyed why to lose weight”; 1 = not at all, 7 = very much; Han et al., 2019) and FSM (α = 0.82; Price et al., 2018) by indicating to what extent they agreed with the corresponding statements. Participants were then asked to indicate the extent to which they were persuaded by the ad and their willingness to try the weight-loss program (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Finally, they completed demographic and suspicion questions and were paid. Suspicion measures revealed that no participants were aware of the true objective of this study.

Results

The results revealed that the manipulations in Study 3 were all successful. Regarding feasibility, an ANOVA showed that compared with a desirability appeal, participants thought a feasibility appeal conveyed more messages about how to lose weight (Mfeasibility = 3.94, SD = 1.92; Mdesirability = 2.93, SD = 1.64; F (1, 314) = 24.19, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.072). The main effects of ad type and FSM, as well as the interactive effects of the three factors were nonsignificant (ps > 0.10). Regarding desirability, the results showed that compared with a feasibility appeal, participants were more likely to agree that a desirability appeal conveyed more about why to lose weight (Mfeasibility = 3.67, SD = 1.60; Mdesirability = 4.78, SD = 1.87; F (1, 314) = 34.56, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.099). The main effects of other factors and their interactions were not significant (ps > 0.10). Regarding FSM, the results revealed that participants in the strong FSM condition agreed more with the statement that people can make a new start than their counterparts in the weak FSM condition (Mweak FSM = 3.44, SD = 1.61; Mstrong FSM = 4.13, SD = 1.37; F (1, 314) = 18.29, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05). The other effects were nonsignificant.

A three-way ANOVA with ad persuasiveness as the dependent variable and ad type, FSM, and appeal type as well as their interactions as independent variables revealed a significant main effect of FSM (F (1, 314) = 4.98, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.016). The main effects of ad type and appeal type, however, were nonsignificant (p > 0.10). Similar to previous studies, the interactive effect of ad type and FSM was still significant (F (1, 314) = 15.83, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.048), as were the interaction of ad type and appeal type (F (1, 314) = 20.28, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.061) and the interaction of FSM and appeal type (F (1, 314) = 23.36, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.069). More importantly, the results revealed a significant three-way interaction of ad type, FSM and appeal type (F (1, 314) = 3.13, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.010). Specifically, when the appeal focused on the feasibility of the program, the progression ad was more persuasive than the before/after ad for consumers with weak FSM (Mprogression = 5.39, SD = 1.48; Mbefore/after = 4.48, SD = 1.64; p < 0.05), while the differences of their persuasiveness were nonsignificant for consumers with strong FSM (Mprogression = 4.53, SD = 1.62; Mbefore/after = 4.42, SD = 1.55; p > 0.10). However, when the appeal emphasized the desirability of the program, participants in the weak FSM condition felt similarly persuaded by the progression ad and the before/after ad (Mprogression = 3.90, SD = 1.39; Mbefore/after = 3.97, SD = 1.74; p > 0.10), whereas participants in the strong FSM condition were significantly more persuaded by the before/after ad than the progression ad (Mprogression = 4.14, SD = 1.66; Mbefore/after = 6.24, SD = 1.40; p < 0.05).

Another three-way ANOVA with willingness to try as the dependent variable yielded similar results: the main effect of FSM (F (1, 314) = 5.95, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.013), the interactive effect of ad type and FSM (F (1, 314) = 13.39, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.041), and the three-way interaction of ad type, FSM, and appeal type (F (1, 314) = 4.29, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.013) were significant. In particular, when the appeal stressed the feasibility of the program, the effectiveness of different ad types was only significantly different for consumers in the weak FSM condition: participants were more willing to try the program when they saw a progression ad than a before/after ad (Mprogression = 5.22, SD = 1.49; Mbefore/after = 4.36, SD = 1.54; p < 0.05). In contrast, when the appeal emphasized the desirability of the program, only participants in the strong FSM condition were differently persuaded by different ad types: participants in the before/after condition had significantly higher willingness to try the program than those in the progression condition (Mprogression = 4.06, SD = 1.52; Mbefore/after = 6.18, SD = 1.01; p < 0.05). These results are represented in Fig. 3, replicating the findings of Studies 1 and 2 and supporting our predictions.

Discussion

Study 3 examined the mediating roles of feasibility and desirability using a moderation approach to complement the mediation approach used in Study 2. The findings in this study also provided further empirical evidence for the matching effect of ad type and FSM on persuasion. By changing the advertising context, replacing the stimuli, and adjusting the sequence of manipulation, this study verified the robustness of the proposed effects.

General discussion

Collectively, the three studies supported our hypotheses regarding the interactive effect of ad type and FSM on persuasion, as well as the mechanisms underlying this effect. Study 1 revealed that a match between ad type (progression vs. before/after) and consumers’ FSM (weak vs. strong) leads to greater persuasiveness of a health ad. Study 2 replicated the findings in Study 1 by measuring consumers’ QR code scanning behaviors and revealed the mediating roles of perceived feasibility and desirability in the proposed matching effects. Finally, Study 3 examined the underlying mechanisms through a moderation approach. These conclusions not only enrich and expand the existing theoretical literature but also provide practical implications for managers and marketers in the health industry.

Theoretical contributions

First, the current research enriches the persuasion literature. Persuasion has always been a major topic in industrial circles and has attracted many researchers from the fields of advertising, marketing, and applied psychology to investigate how to improve it (Han et al., 2016). Focusing on the health advertising context, this research revealed the difference in the persuasiveness of different types of ads (progression vs. before/after) under different FSMs (weak vs. strong). At present, which type of health ad is more effective is still equivocal (Cian et al., 2020), and the current research puts forward the most applicable condition of different types of health ads by identifying the role of FSM in influencing the persuasiveness of different ad types. In addition, although the existing research has investigated the effectiveness of different types of ads for consumers with different individual characteristics (e.g., moral identity, political ideology; Kidwell et al., 2013; Winterich et al., 2012), little literature has focused on the effect of FSM, a belief rooted in a person’s system of thought and will change with circumstances, on persuasion. Therefore, the present study also extends previous research that holds the view that consumers’ cognitive, attitudinal and affective characteristics should be taken into account when designing a particular type of ad (Cesario et al., 2004; Han et al., 2016; Kidwell et al., 2013; Rimer & Kreuter, 2006).

Furthermore, the present work contributes to burgeoning research on FSM (Bi et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2020; Dai et al., 2015; Price et al., 2018). Previous research has documented that the objective start point (e.g., the first day of a week) increases individuals’ self-improvement motivations (Mukhopadhyay & Johar, 2005) and encourages them to abandon bad habits (Crockett et al., 2013). Goals such as diet and exercise set at the start point are more motivated to achieve than at other times (Dai et al., 2014). In addition, a fresh start mindset can increase consumers’ variety-seeking behaviors and improve their evaluations of ads that advocate transformative changes (Price et al., 2018). By introducing FSM into the field of brand crisis management, Chen et al. (2020) found that FSM influences individuals’ attribution tendencies and forgiveness behaviors to different brand crisis types. Our research introduces the fresh start mindset into a new marketing strategy, namely, the health ad that encourages change and expands relevant research on the fresh start mindset and its consequent effects.

Finally, this research also extends the construal level theory and provides a potential explanation for the “black box” of persuasion by investigating the effect of feasibility and desirability. Construal level theory provides a theoretical framework that explains how the psychological distance of an event or object influences one’s decision-making and judgment, which has attracted extensive researchers to conduct studies around it (Hsieh & Yalch, 2020; Lu et al., 2013). Previous research on health persuasion has demonstrated several underlying processes through which a health message influences persuasion, such as processing fluency (Kidwell et al., 2013), feeling right (Cesario et al., 2004), and efficiency (Han et al., 2016). Based on construal level theory, the present research tests the mediating roles of feasibility and desirability in the matching effects of ad type and FSM on health persuasion, therefore contributing to the research on construal level and providing a new angle of view for the mechanisms of persuasion.

Managerial implications

The current work also provides practical insights for health product manufacturers and policymakers concerned about public health issues by focusing on how to improve the persuasiveness of different types of health ads that promise change. In the marketplace, health ads that promise the changes products or services can make are now very popular, and these ads often present the changes in a before/after way than a progression way. The current research demonstrated that a strong FSM triggered by marketing strategies (e.g., ad messages) increases the persuasiveness of before/after ads. We suggest that practitioners should consider the effect of consumers’ FSM when designing change ads for health products. For example, practitioners could attempt to establish consumers’ FSM by using appeals (e.g., “Say hello to the new day”) or imageries (e.g., a rising sun) in the advertising context. In particular, practitioners could employ these types of ads in certain time periods such as New Year’s Day, consumers’ birthdays, and the first day of a new semester.

Limitation and future research

This research has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, the current research only manipulated different ad types by presenting different images but neglected other advertising elements such as text and videos. In marketing practice, using text or videos to show promised changes in ads is also popular, and it would be practical for future research to examine whether the text or videos in change ads can have similar effects on persuasion. Prior research has suggested that FSM is correlated with time perspective (Price et al., 2018). Future studies could examine alternative accounts such as future orientation and present-hedonistic orientation (Chen et al., 2019; Wojtkowska et al., 2021).

Another avenue for our research lies in the stimuli that elicit FSM. Previous literature identifies numerous timepoints that could serve as time markers (i.e., temporal landmarks), such as meaningful personal events (e.g., moving to a new city, the first experience of publishing an article in a journal) and vivid public events (e.g., COVID-19, the 2008 Being Olympic Games) (Bi et al., 2021; Hennecke & Converse, 2017). Scholars might be interested in examining whether different types of temporal landmarks moderate the effects described herein. Moreover, other measures can be employed to capture ad persuasiveness. The aim of persuasion is to enhance information receivers’ attitudes, stimulate their interest, and increase their actual behavior. Based on this notion, we captured persuasiveness by measuring attitude toward the app on a Likert scale (Study 1), scanning behavior (Study 2), and persuasion and willingness to try (Study 3). Future studies can employ approaches such as eye-tracking and neuroscientific technologies to measure ad persuasion.

In addition, although the effect of the number of images (three, five, six) in progression conditions is somewhat ruled out, the present work did not test whether the degree of variation between two adjacent images will affect consumer perception. In other words, if the two adjacent images in progression ads vary greatly (i.e., the contrast is obvious), will the difference between progression ads and before/after ads attenuate? It would be worthwhile for future research to explore this question. Furthermore, researchers can try to investigate potential boundary conditions of the matching effect in the future. For example, message framing (positive vs. negative) may affect the interplay between ad type and FSM in persuasion.

References

Bi, S., Perkins, A., & Sprott, D. (2021). The effect of start/end temporal landmarks on consumers’ visual attention and judgments. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 38(1), 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2020.04.007

Cesario, J., Grant, H., & Higgins, E. T. (2004). Regulatory fit and persuasion: Transfer from “feeling right.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(3), 388–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.3.388

Chen, S., Wei, H., Meng, L., & Ran, Y. (2019). Believing in karma: The effect of mortality salience on excessive consumption. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1519. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01519

Chen, S., Wei, H., Ran, Y., Li, Q., & Meng, L. (2021). Waiting for a download: The effect of congruency between anthropomorphic cues and shopping motivation on consumer patience. Psychology & Marketing, 38(12), 2327–2338. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21564

Chen, S., Wei, H., Ran, Y., & Meng, L. (2020). Rise from the Ashes or Repeat the Past? The Effects of Fresh Start Mindset (FSM) and Brand Crisis Type on Consumer Forgiveness. Nankai Business Review International, 23(4), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1008-3448.2020.04.006

Cian, L., Longoni, C., & Krishna, A. (2020). Advertising a desired change: When process simulation fosters (vs. hinders) credibility and persuasion. Journal of Marketing Research, 57(3), 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243720904758

Crockett, D., Downey, H., Fırat, A. F., Ozanne, J. L., & Pettigrew, S. (2013). Conceptualizing a transformative research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1171–1178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.009

Dai, H., Milkman, K. L., & Riis, J. (2014). The fresh start effect: temporal landmarks motivate aspirational behavior. Management Science, 60(10), 2563–2582. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1901

Dai, H., Milkman, K. L., & Riis, J. (2015). Put your imperfections behind you: Temporal landmarks spur goal initiation when they signal new beginnings. Psychological Science, 26(12), 1927–1936.

Han, D., Duhachek, A., & Agrawal, N. (2016). Coping and construal level matching drives health message effectiveness via response efficacy or self-efficacy enhancement. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(3), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw036

Han, N. R., Baek, T. H., Yoon, S., & Kim, Y. (2019). Is that coffee mug smiling at me? How anthropomorphism impacts the effectiveness of desirability vs. feasibility appeals in sustainability advertising. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 352–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.06.020

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford.

Hennecke, M., & Converse, B. A. (2017). Next week, next month, next year: How perceived temporal boundaries affect initiation expectations. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(8), 918–926. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1948550617691099

Hsieh, M., & Yalch, R. F. (2020). How a maximizing orientation affects trade-offs between desirability and feasibility: The role of outcome‐ versus process‐focused decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 33(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2146

Kergoat, M., Meyer, T., & Legal, J. B. (2019). Influence of “health” versus “commercial” physical activity message on snacking behavior. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 37(2), 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1108/jcm-07-2018-2765

Kidwell, B., Farmer, A., & Hardesty, D. M. (2013). Getting liberals and conservatives to go green: Political ideology and congruent appeals. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(2), 350–367. https://doi.org/10.1086/670610

Kim, K., Kim, S., Corner, G., & Yoon, S. (2019). Dollar-off or percent-off? Discount framing, construal levels, and advertising appeals. Journal of Promotion Management, 25(3), 314–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2019.1557808

Kirmani, A., & Wright, P. (1989). Money talks: Perceived advertising expense and expected product quality. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 344–353. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2489515

Lewis, M., Whitler, K. A., & Hoegg, J. (2013). Customer relationship stage and the use of picture-dominant versus text-dominant advertising: A field study. Journal of Retailing, 89(3), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2013.01.003

Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (1998). The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(July), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.936532

Liu, W. (2008). Focusing on Desirability: The effect of decision interruption and suspension on preferences. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(4), 640–652. https://doi.org/10.1086/592126

Lu, J., Xie, X., & Xu, J. (2013). Desirability or feasibility: Self–other decision-making differences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(2), 144–155.

Meyer, J. H., De Ruyter, K., Grewal, D., Cleeren, K., Keeling, D. I., & Motyka, S. (2020). Categorical versus dimensional thinking: improving anti-stigma campaigns by matching health message frames and implicit worldviews. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(2), 222–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00673-7

Mayer, N. D., & Tormala, Z. L. (2010). “Think” versus “feel” framing effects in persuasion. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(4), 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210362981

Milfeld, T., Haley, E., & Flint, D. J. (2021). A fresh start for stigmatized groups: The effect of cultural identity mindset framing in brand advertising. Journal of Advertising. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1913264

Mukhopadhyay, A., & Johar, G. V. (2005). Where there is a will, is there a way? Effects of lay theories of self-control on setting and keeping resolutions. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 779–786. https://doi.org/10.1086/426611

Price, L. L., Coulter, R. A., Strizhakova, Y., & Schultz, A. E. (2018). The fresh start mindset: Transforming consumers’ lives. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(1), 21–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx115

Reczek, R. W., Trudel, R., & White, K. (2018). Focusing on the forest or the trees: How abstract versus concrete construal level predicts responses to eco-friendly products. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 57(6), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.06.003

Rimer, B. K., & Kreuter, M. W. (2006). Advancing tailored health communication: A persuasion and message effects perspective. Journal of Communication, 56(suppl_1), S184–S201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00289.x

Schlosser, A. E. (2003). Experiencing products in the virtual world: The role of goal and imagery in influencing attitudes versus purchase intentions. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(2), 184–198. https://doi.org/10.1086/376807

Spencer, S. J., Zanna, M. P., & Fong, G. T. (2005). Establishing a causal chain: Why experiments are often more effective than mediational analyses in examining psychological processes. Journal of personality and social psychology, 89(6), 845–851.

Strizhakova, Y., Coulter, R. A., & Price, L. L. (2021). The fresh start mindset: A cross-national investigation and implications for environmentally-friendly global brands. Journal of International Marketing, 29(4), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069031X211021822

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological review, 117(2), 440–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018963

Wang, R. J., Malthouse, E. C., & Krishnamurthi, L. (2015). On the go: How mobile shopping affects customer purchase behavior. Journal of Retailing, 91(2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2015.01.002

Wang, Z., Mao, H., Li, J., Y., & Liu, F. (2017). Smile big or not? Effects of smile intensity on perceptions of warmth and competence. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(5), 787–805. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw062

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Winterich, K. P., Zhang, Y., & Mittal, V. (2012). How political identity and charity positioning increase donations: Insights from moral foundations theory. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(4), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.05.002

Wojtkowska, K., Stolarski, M., & Matthews, G. (2021). Time for work: Analyzing the role of time perspectives in work attitudes and behaviors. Current Psychology, 40(12), 5972–5983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00536-y

Zhao, M., Hoeffler, S., & Zauberman, G. (2011). Mental simulation and product evaluation: The affective and cognitive dimensions of process versus outcome simulation. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(5), 827–839. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.48.5.827

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Youth Project of Philosophy and Social Sciences of Guangdong Province of China (No. GD21YGL17), the Youth Innovative Talents Project of Guangdong Provincial Education Department of China (No. 2021WQNCX208), and the Research Foundation of Shenzhen Polytechnic (No. 6022312031S). The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the university research committees, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Siyun Chen and Sining Kou share the co-first authorship.

Appendices

Appendix A

Materials for progression and before/after ads of teeth-whitening powder in Study 1.

Appendix B

Materials for progression and before/after ads of hair-restorer in Study 2.

Appendix C

Materials of progression and before/after ads of weight-loss program in Study 3.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Kou, S. & Shu, L. Gradually or immediately? The effects of ad type and fresh start mindset on health persuasion. Curr Psychol 42, 28285–28297 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03471-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03471-7