Abstract

Sudan is one of the Islamic countries where extramarital sex is religiously forbidden and socially unacceptable. However, increasing numbers of university students become engaged in premarital sex practices, which increases their risk of contracting STIs, including HIV, and puts them into conflicts with their religious beliefs. As little is known about the motivations for abstinence from premarital sex, this study aimed to identify these psychosocial determinants. Using a cross-sectional design, a sample of 257 students between18 and 27 years old was recruited from randomly selected public and private universities in Khartoum. The participants filled out an online questionnaire based on the Integrated Change Model (ICM) to assess their beliefs and practices about abstinence from premarital sex. The analysis of variances (MANOVA) showed that the students who reported being sexually active differed significantly from abstainers in having more knowledge about HIV/AIDS, higher perception of susceptibility to HIV, more exposure to cues that made them think about sex and a more positive attitude towards premarital sex. The abstainers had a significantly more negative attitude towards premarital sex, higher self-efficacy to abstain from sex until marriage and perceived more peer support and norms favouring abstinence from sex until marriage. These findings suggest that promoting abstinence from sex until marriage among university students in Sudan, which aligns with the Sudanese religious values and social norms, requires health communication messages addressing these potential determinants. However, given that sexual encounters still may occur, health communication messages may profit from a more comprehensive approach by also addressing the need for condom use for those unwilling to refrain from sex.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The HIV epidemic in Sudan is classified as a low epidemic, as the estimated HIV prevalence among adults aged 15–49 is about 0.2% (UNAIDS, 2020a). However, HIV still represents a public health problem of high importance in Sudan because of the huge gaps between the current situation and the 90–90–90 targets, which were supposed to be achieved by 2020 according to the 2016 United Nations Political Declaration on Ending AIDS (UNAIDS, 2019). According to recent reports, only less than 40% of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) know their status, fewer than 15% are receiving treatment and no reports are available about the percentage of those on treatment who achieved viral suppression. In addition, the lack of financial resources, civil wars, political instability and increasing poverty have undermined previous efforts and could influence future endeavours to achieve these targets (Ismail et al., 2015).

Men who have sex with men (MSM) and female sex workers (FSW) are considered key populations in Sudan that need to be targeted with HIV prevention interventions. Interventions among these key populations are implemented in several states in Sudan and led by non-governmental organizations (NGOs). These interventions use different approaches to reach and deliver preventive packages to these key populations (UNAIDS, 2020b). However, less attention is given to HIV prevention among university students in Sudan, although HIV is predominantly transmitted through heterosexual practices in Sudan (Shakiba et al., 2021) and previous surveys conducted by the Sudan National AIDS Program (SNAP) showed a high prevalence of risky heterosexual behaviours among this population (unpublished reports).

Several studies in different communities have shown that the university lifestyle is commonly associated with risky behaviours, including sexual activities (Chi et al., 2012; Majer et al., 2019; Omoteso, 2006). This association has been attributed to parental guidance's weakening after joining the university in addition to the increased exposure to potential sexual partners (M. Akibu et al., 2017a, 2017b; Farrow & Arnold, 2003). The increase in sexual practices among university students has also been observed in some conservative Islamic countries, including Sudan, despite the religious values and prevailing social norms prohibiting all types of premarital sex (Elshiekh et al., 2020; Hedayati-Moghaddam et al., 2015; Massad et al., 2014; Raheel et al., 2013). In a survey conducted by the Sudan National AIDS Program (SNAP) several years ago among university students in Sudan aged 16–25, 12.5% were sexually active. Male students reported higher sexual activity than their female counterparts did. Condom use during first and last sexual intercourse was reported by only 32% of the sexually active participants (unpublished report).

Although all types of unprotected extramarital sex carry the risk of acquiring HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI), premarital sex is usually associated with a higher risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, as well as unwanted pregnancy (Alo, 2016; Ghebremichael & Finkelman, 2013) because youths who practice sex before marriage are more likely to have multiple sex partners and less likely to use condoms (Alo, 2016; Santelli et al., 2004). A Sudanese study also found that having the first sexual encounter at a young age was one of the risk factors associated with HIV/AIDS in Sudan (Mohamed & Mahfouz, 2013). Therefore, university students in Sudan have been identified as an important target group for HIV prevention interventions (Elshiekh et al., 2021, 2020; Mohamed, 2014).

The different terms used to define abstinence from premarital sex reflect how different health professionals and religious scholars look at it. For example, health professionals commonly use terms such as "postponing sex", "never had vaginal sex" or "refraining from further sexual intercourse if sexually experienced" as they consider it a health issue (Santelli et al., 2017). On the other side, religious scholars describe abstinence as a "commitment to chastity", reflecting the religious origin of their view (Santelli et al., 2017). This difference in views has also been reflected in the response of these important stakeholders to abstinence promotion as a strategy to prevent HIV, not only in conservative Islamic communities but also in many western liberal communities (Horanieh et al., 2020; Maulana et al., 2009; Santelli et al., 2017). As a result, two different approaches have been widely used in behavioural interventions aiming to promote abstinence from sex to prevent HIV transmission: Abstinence-only-until marriage (AOUM) and abstinence‐plus programs (Santelli et al., 2017; Underhill et al., 2008).

Abstinence-only until marriage (AOUM) is the term given to programs that focus exclusively on promoting abstinence. AOUM programs consider abstinence from sexual activity the only certain way to avoid out-of-wedlock pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, and other associated health problems. This approach was first adopted in the United States in the early 1980s and received federal support and funding since1996 (Santelli et al., 2017). AOUM strategy has been supported by religious leaders and faith-based organizations in different communities as they look at mutually faithful monogamous relationships in the context of marriage as the expected standard of human sexual activity, which is in line with all religious values. In addition, religious leaders agree with the messages conveyed by AOUM programs emphasizing that sexual activity outside of the context of marriage is likely to have harmful social, psychological and physical effects (Horanieh et al., 2020; Kandasamy et al., 2018; Santelli et al., 2017; Trinitapoli, 2011a).

Oppositely, many health professionals have been criticizing AOUM programs both scientifically and ethically. They outline that AOUM programs lack scientific evidence of efficacy and often fail to prevent premarital sex or reduce STD infections (Brückner & Bearman, 2005; Kantor et al., 2008; Santelli et al., 2017). Previous systematic reviews of abstinence-only curricula also revealed that the best implemented and evaluated programs in high-income countries failed to delay the initiation of sexual intercourse or to produce other demonstrable reductions in HIV risk behaviours (Kirby et al., 2007; Kohler et al., 2008; Underhill et al., 2007a, 2007b). This failure was attributed to several reasons, including the fact that in western communities, few people remain abstinent until marriage; many do not or cannot marry, and most initiate sexual intercourse and other sexual behaviours as adolescents (Santelli et al., 2017), although this may not be generalizable to Islamic communities where abstinence from sex until marriage is the norm. Another reason is the rising age of marriage globally due to poverty and the increased cost of marriage. This approach was also criticized for violating youth`s right to health information and providing misleading information about other protective methods (Kantor et al., 2008; Raymond et al., 2008; Santelli et al., 2017).

Alternatively, abstinence‐plus interventions, as defined by Dworkin and Santelli, "provide participants with a hierarchy of safe-sex strategies. At the top of the hierarchy is promoting sexual abstinence as the safest route to HIV prevention. Recognizing that some participants will not be abstinent, abstinence-plus approaches encourage individuals also to use condoms and to adopt other safer-sex strategies" (Dworkin & Santelli, 2007; Underhill et al., 2008). Some of these interventions have positively impacted both short and long-term safe sex practices and abstinence (Aarons et al., 2000; Jemmott III et al., 1998; O'Donnell et al., 2002; Underhill et al., 2007a, 2007b). A previous systematic review also showed that the abstinence-plus approach effectively promoted both abstinence and condom use in high-income countries and had no undermining effect on any of the behavioural outcomes, including the incidence of sex, frequency of sex, sexual initiation, or condom use (Underhill et al., 2007a, 2007b).

Besides, previous research has shown that the interventions which incorporate a community's social norm are more likely to be accepted and more extensively implemented (Marston & King, 2006; Willems, 2009). The abstinence‐plus approach has the advantage of respecting the conservative communities' religious values and social norms while addressing health professionals' scientific and ethical concerns against AOUM programs. Some studies suggest that interventions solely focusing on sexual risk reduction and neglecting abstinence run a risk of becoming rejected since they are regarded as potentially promoting premarital sex in Muslim communities (Elshiekh et al. 2021; Kamarulzaman, 2013). Therefore, incorporating abstinence, a religious obligation and highly valued norm in Muslim communities (Elshiekh et al., 2021; Horanieh et al., 2020), could promote religious leaders' support and facilitate programs implementation (Willems, 2009).

Given this dilemma and the fact that a significant number of Sudanese university students may decide not to refrain from sex before marriage, it may be better to adopt a more comprehensive approach by promoting abstinence as long as possible to help those who are not yet sexually active remain abstinent, and promoting consistent condom use to protect those sexually active. However, the development of an effective abstinence-plus intervention requires identifying the determinants of both abstinence and consistent condom use separately. Besides, such a comprehensive approach should aim to reduce HIV—related stigma by developing and implementing culturally adapted stigma reduction interventions.

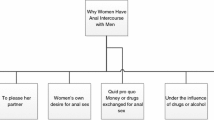

To promote abstinence from sex among university students, it is crucial to identify the most relevant factors that may foster and predict such a choice, including the psychosocial ones. The Integrated Model for Change (the I-Change Model, see Fig. 1), which integrates several social cognitive theories, is one of the models that has been used successfully to understand and predict health behaviours, including sexual health behaviours (De Vries, 2017; De Vries et al., 2014; De Vries et al., 2005; Dlamini et al., 2009; Eggers et al., 2016). According to the I-Change Model, pre-motivational factors, including knowledge about HIV/AIDS, the exposure to cues that may prompt a person about a certain behaviour (i.e., sex and/or abstinence), and risk perceptions determined by susceptibility to and severity of HIV and other social consequences of premarital sex, could influence students’ awareness about the need to abstain from premarital sex or delay sex. When aware, students' decision to abstain from premarital sex, as suggested by the I-Change Model, will also be determined by motivational and post-motivational factors, including their attitude towards abstinence, the social influence perceptions (such as social norms and the perceived behaviour of others) on their sexual behaviour and their perceived ability (self-efficacy) to remain abstinent (De Vries et al., 2005; Dlamini et al., 2009).

Despite their importance, these psychosocial determinants of sexual behaviours, including abstinence, have been poorly studied among university students in Sudan. A recent cross-sectional study reported serious gaps in comprehensive correct HIV/AIDS knowledge among university students in Sudan, especially among females (Elbadawi & Mirghani, 2016). However, the correlation between poor knowledge and sexual behaviours was not investigated. According to the previous survey conducted in 2010 by SNAP, 19.8% of university students in Sudan reported a high perception of HIV risk, 29.5% had a moderate perception, 19.4 had a low perception and 31% reported not being at risk at all. The association between their HIV risk perception and their sexual behaviours and the importance of other motivational determinants were not tested. However, previous studies among adolescents and university students in other countries did identify an association between low HIV-risk perception and sexual activity (Idele et al., 2003; Khalajabadi Farahani et al., 2018; Sychareun et al., 2013). Similar association was also suggested by a recent qualitative study among Sudanese university students (Elshiekh et al., 2021). Regarding cues, a recent qualitative study alluded to the association between cues, such as watching pornographic movies, and abstinence cues, such as having experience with HIV-infected persons, and Sudanese students' decision to engage in or abstain from premarital sex (Elshiekh et al., 2021). However, to the best of our knowledge, this association has never been studied quantitatively in Sudan before. Previous studies among university students in two similar Muslim communities showed that premarital sex was significantly associated with watching pornographic movies (Khalajabadi Farahani et al., 2018; Raheel et al., 2013).

Sudanese university students' attitudes towards abstinence and sexual practices have only been explored in a recent qualitative study. The study suggested that most of the university students in Sudan had a positive attitude towards abstinence. However, sexually active students also perceived some advantages of engaging in sexual practices, such as sexual pleasure and proving adulthood (Elshiekh et al., 2021). Practising sex before marriage is a sin in Islam and the social stigma associated with it could destroy the whole family`s reputation in Sudan. Therefore, religious leaders, parents and other family members strongly support abstinence from premarital sex. However, the previous qualitative study suggested that peers had a greater influence on Sudanese students' sexual behaviours (Elshiekh et al., 2021). This contradicted the results of a previous systematic review that found no conclusive evidence about the role of peers in young people`s sexual behaviour in Sub-Saharan Africa (Fearon et al., 2015). Therefore, further (quantitative) assessments of the role of peers are highly needed as other international studies also point at the importance of peers in the uptake of sexual behaviour (Uecker, 2015; Wetherill et al., 2010).

Self-efficacy and its association with university students' sexual practices have been poorly studied among this population as well despite the accumulated evidence of its importance from several studies in neighbouring African and other countries (Abousselam et al., 2016; Rubens et al., 2019; Taffa et al., 2002). This necessitates assessing the role of self-efficacy in abstaining and identifying the problematic situations that could weaken the Sudanese students' ability to abstain from sex until marriage.

Consequently, this study aimed to identify the potential psychosocial determinants related to sexual abstinence to understand this behaviour better and provide indications for interventions promoting maintenance of abstinence from sex until marriage among this population as long as possible according to the Islam recommendation.

Methods

Design

This is an online cross-sectional study of the psychosocial determinants of premarital sexual practices among university students in Khartoum. For this study's purpose, the Integrated Change Model, the I-Change Model (Fig. 1), was used as a theoretical model (De Vries, 2017; de Vries et al., 1988; Eggers et al., 2016).

Recruitment and Procedures

Three public and three private universities were selected randomly from 35 public and private universities in Khartoum state. The inclusion criteria consisted of all undergraduate students in the selected public and private universities in Khartoum who consented to participate through the electronic questionnaire. Postgraduate students were excluded. Initially, to obtain the official approval to conduct the study, the principal researcher met the deans of students' affairs in the selected universities and explained the study's nature and objectives. Following their approvals, 3–5 lecture rooms in each university were selected randomly. The principal researcher explained the study to the students, discussed its objectives and provided them with study information letters. This letter provided a complete description of the study and its objectives and provided the participants with access instructions regarding the online questionnaire. Following the initial round of random data collection, it was observed that more sexually active participants were needed to enable the comparison between the sexually active and abstainers. Therefore, three sexually active university students, who were identified by HIV counsellors at three different universities, were asked to invite their sexually active peers to fill the online questionnaire (snowball recruitment). All of those recruited through the snowball technique were also undergraduate university students and none of them was a client of an HIV counselling clinic. An anonymous online questionnaire (in the Arabic language) was used as a data collection method to to increase the validity of the data provided by the participants because of the sensitivity of disclosing sexual behaviours in Sudan's conservative community. In addition to the invitation letter, the introduction part of the questionnaire presented the study and explained its objectives. It was clearly stated in the introduction that participation was voluntary. The participants were then requested to respond to the online questionnaire through their smartphones, laptops or computers and answer all the questions. To preserve students' privacy and confidentiality, participants' identifiers such as their names and phone numbers were not included in the questionnaire.

Measurement

To design the study questionnaire, some of the items were derived from the findings of a recently conducted qualitative study of the sexual behaviours among Sudanese university students to ensure the cultural adaptation of the questionnaire. Other items were derived from questionnaires of similar studies (De Vries et al., 2014; Eggers et al., 2017; Elshiekh et al., 2021). The I-Change model was used as a theoretical base for the development of the online questionnaire as well. The questionnaire was designed to measure pre-motivational, motivational and post-motivational determinants of premarital sex. These determinants included knowledge about HIV/AIDS, HIV risk perception, abstinence and premarital sex cues, attitudes towards premarital sex, social influence on sexual behaviour, self-efficacy and intentions to abstain from sex until marriage. A pilot was performed with twenty students other than the study participants and according to its results, no necessary changes were needed. Factor analysis was conducted to assess the validity of the questionnaire for each construct of the I-Change model and Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to ensure the internal consistency of each construct items (Akeem, 2015).

Premarital sexual practice and abstinence as behavioural outcome variables were measured by two questions asking the participants if they ever practised vaginal or anal sex (yes, no). Although sexual activity includes many forms, we focused on penetrative anal and vaginal sex considering the study`s main objective, which is preventing HIV among university students. Those who had never practised vaginal or anal sex were considered abstainers. The students who stated that they had practised vaginal or anal sex were considered sexually active. Accordingly, sexually active participants were coded as (0) and abstainers (1).

To assess participants' knowledge about HIV/AIDS, 16 statements were used (Cronbach's alpha = 0.62). These included statements about HIV and how it is transmitted, prevented and treated, such as "Someone who looks healthy can be infected with HIV" and "HIV treatments help HIV-infected people to live normally for a longer time" (Table 1). Participants could respond to each statement with yes, no or not sure. Participants' responses to questions were coded as (1) for correct answers and (0) for incorrect or not sure responses. High mean scores in knowledge items indicated higher knowledge, while low mean scores indicated poor knowledge about HIV.

To assess cues to sexual behaviours, six statements were included in the questionnaire. These included four statements about cues believed to encourage abstinence and two statements about sex cues. The abstinence cues included experience with PLWHA, such as "Do you know someone who dies of HIV/AIDS?" and religious cues, such as "Do you listen to religious lectures about abstinence?" Premarital sex cues were assessed using questions such as "Do you watch pornographic movies and videos?" (Table 1). Participants could answer with yes (1) or no (0) for each item. High mean scores indicated more exposure to the specific cue, while low mean scores indicated less exposure to that cue. The Cronbach's alpha value for the six cue items was low (0.32). However, these categorical items were treated as an index and were not intended to measure the same dimension.

The questionnaire assessed the participants' perceptions of HIV severity and susceptibility separately. To assess their perception of HIV severity, four items, such as "If I were to contract HIV, I would suffer from serious psychological distress", were used (α = 0.78) (Table 2). Participants could reply on a five-point Likert scale ranging from -2 (strongly disagree) to + 2 (strongly agree). To assess the participants' perception of how susceptible they felt to HIV, three items such as "How likely that you will get HIV infection if you practice unprotected vaginal intercourse?" were used (α = 0.64) (Table 2). Participants could reply on a five-point Likert scale ranging from -2 (very unlikely) to + 2 (very likely). The participants' comparative risk perception was assessed by asking each participant: "In comparison with other students, how likely is it that you will get infected by HIV?" Participants could reply on a five-point Likert scale ranging from -2 (much less likely) to + 2 (much more likely) (Table 2). High mean scores indicated high perceptions of HIV severity and susceptibility, while low mean scores indicated low perceptions.

To assess the perceived advantages of premarital sex (pros), four items such as (If I practice premarital sexual intercourse, I will gain a lot of sexual skills) were used (α = 0.82) (Table 2). The cons of premarital sex were assessed by five items such as (If I practice premarital sexual intercourse, I will be exposed to the risk of HIV and other STIs) (α = 0.63) (Table 2). Participants could reply on a five-point Likert scale ranging from − 2 (strongly disagree) to + 2 (strongly agree) for all attitude items. High mean scores indicated high perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of premarital sex, while low mean scores indicated low perceptions.

Social influence on the students' sexual behaviour was assessed with eleven items (Table 2). Based on factor analysis (Beavers et al., 2013), the eleven social influence items were grouped into two categories: five items assessed peers influence, including peer norms, support and modelling (α = 0.78) and six items assessed the influence of parents, religious scholars and health professional collectively (α = 0.91). The items included statements about social norms such as (My parents believe that I should abstain from sexual intercourse until marriage) and statements about social support such as (Most of my friends support me to abstain from sexual intercourse until marriage). Participants could reply on a five-point Likert scale ranging from -2 (strongly disagree) to + 2 (strongly agree). The influence of social modelling was assessed by asking each participant, "How many of your friends practice sexual intercourse before marriage?" The participants could reply on a five-point Likert scale ranging from -2 (none of them) to + 2 (all of them). High mean scores indicated more social influence to abstain from premarital sex, while low mean scores indicated less social influence.

Self-efficacy to abstain from sex until marriage was assessed with five statements such as (I would find it difficult not to have sexual intercourse when my sexually active peers challenge me) (α = 0.90) (Table 2). Participants could reply to self-efficacy items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from − 2 (strongly agree) to + 2 (strongly disagree) so that higher scores indicated higher self-efficacy to abstain from sex until marriage. High mean scores indicated high self-efficacy to abstain from premarital sex, while low mean scores indicated low self-efficacy.

The participants' intention to abstain from sex until marriage was assessed with two statements, such as "I have the intention to abstain from premarital sexual intercourse during my university study" (α = 0.89) (Table 2). Participants could reply on a five-point Likert scale ranging from -2 (strongly disagree) to + 2 (strongly agree). High mean scores indicated high intentions to abstain from premarital sex, while low mean scores indicated low intentions.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24. A descriptive analysis was conducted to describe the study sample. To assess the overall difference between abstainers and sexually active students per each I-Change Model construct, Multivariate analysis of variances (MANOVA) was conducted. MANOVA was also used to identify the significant differences between the two groups regarding each construct item. Bonferroni correction was used to adjust the p-values for multiple comparisons. Results with p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Description of the Sample

Initially, 441 students responded to the online questionnaire. However, 184 participants answered fewer than 75% of the questions; therefore, they were excluded from the study. Two hundred and fifty-seven male and female university students were finally included in the analysis. The participants' age ranged from 18 to 27 (mean age of 21.3). The sample included 170 abstainers (66%) and 87 reported being sexually active (34%). Almost all of the students were Sudanese (98%) and Muslim (99%). The demographic characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 3.

Pre-motivational Determinants

Knowledge about HIV/AIDS

Generally, the participants reported good knowledge about HIV transmission and prevention, although some misconceptions were reported. However, their knowledge about HIV treatments and their role in preventing HIV transmission was remarkably low. MANOVA results showed a statistically significant difference in the overall knowledge about HIV/AIDS between abstainers and sexually active participants (Hotelling’s T = 0.169; F (16,240) = 2.532; p < 0.01) (Table 4). A higher knowledge score among those who reported being sexually active as compared to abstaining participants was observed. Significantly more abstainers knew that HIV could not be transmitted by mosquito bites (p < 0.05) or through hugging PLWHA (p < 0.001). More sexually active students, on the other side, knew that HIV could be transmitted by unprotected anal sex (p < 0.05) and its transmission could be reduced by consistent condom use (p < 0.001) and HIV treatments (p < 0.05).

Cues to Action

In general, the participants reported very low exposure to HIV-related cues, such as knowing someone who died of HIV. In contrast, their exposure to religious cues, such as listening to religious lectures about abstinence, was very high. They also reported moderate exposure to sex cues such as watching pornographic movies. The students who reported being sexually active also reported higher exposure to sex cues. The overall difference in exposure to sex cues between abstainers and sexually active participants with MANOVA was significant (Hotelling’s T = 0.077; F (2,249) = 9.530; p < 0.001) (Table 4). When looking at the items separately, those who reported being sexually active reported significantly higher exposure to pornographic movies and videos (p < 0.001) and erotic stories (p < 0.01) as compared to the abstainers (Table 1). No significant difference in reported exposure to HIV and religious cues was observed between the two groups (Table 4).

Risk Perception

Regarding their perception of HIV severity, the participants generally reported a high perception of the severe adverse health, social and psychological consequences of contracting HIV. However, no difference was observed between the abstainers and sexually active participants in their overall perception of HIV severity using MANOVA (Hotelling’s T = 0.015; F (4,252) = 0.957; p = 0.432) (Table 4). ANOVA also showed no significant difference per HIV severity items (Table 2). On the other hand, the participants' perception of their susceptibility to HIV was relatively low, especially when compared to other students. The sexually active participants reported a significantly higher overall perception of susceptibility to HIV when compared to abstainers (Hotelling’s T = 0.175; F (3,253) = 14.784; p < 0.001) (Table 4). Although no significant difference in their perceived HIV risk due to unprotected vaginal sex was observed, ANOVA revealed that participants who reported being sexually active had a significantly higher perception of susceptibility to HIV following unprotected anal sex (p < 0.05). They also reported higher personal risk perception as compared to abstainers (p < 0.001); however, personal risk perception was low among both groups (Table 2).

Motivational Determinants

Attitude Towards Premarital Sex

Regarding the perceived disadvantages of premarital sex overall, the students reported a high perception of different disadvantages of engaging in premarital sex, such as deviation from their religious beliefs and exposure to HIV and STI. However, they had a very low perception of any negative impacts on their academic performance. MANOVA showed that abstainers reported a higher perception of these disadvantages as compared to sexually active participants (Hotelling’s T = 0.055; F (5,251) = 2.757; p < 0.05) (Table 4). This overall difference could be attributed to the higher perception of the social (p < 0.01) and legal consequences (p < 0.05) of premarital sex among the abstainers, as shown in Table 2. On the other side, and in contrast to their perception of the disadvantages, the overall perception of the advantages of practicing sex before marriage was remarkably low. MANOVA also showed that sexually active participants reported a significantly higher perception of the premarital sex advantages compared to the abstainers (Hottelings T = 0.502; F (5,251) = 25.182; p < 0.001) (Table 4). The participants who reported being sexually active believed more than abstainers that premarital sex was associated with enjoying sexual satisfaction (p < 0.001), gaining money (p < 0.001), being more popular among friends (p < 0.001) and gaining sexual skills (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Social Influence

Regarding peer influence on students' sexual behaviours, the students reported low perception of their friends' and sexual partners' support and norms favouring abstinence from premarital sex. MANOVA showed that abstainers differed significantly from the students who reported being sexually active (Hotelling’s T = 0.335; F (5,251) = 16.839; p < 0.001) (Table 4). The Abstainers reported a higher perception of their peers’ beliefs favouring abstinence from sex until marriage (p < 0.01). They also reported more support from their friends to remain abstinent from sex until marriage (p < 0.001) and had fewer numbers of sexually active friends (p < 0.001). Oppositely, the participants' overall perception of their parents, health professional and religious leaders' norms and support to remain abstinent from sex until marriage was very high. However, no significant difference concerning their overall influence on students' sexual behaviour was observed between the abstainers and sexually active participants and no differences in their support or norms favouring abstinence from sex until marriage was identified between the two groups (Table 2).

Self-efficacy

Concerning the students' self-efficacy to abstain from sex until marriage, they generally reported low confidence in their ability to abstain. Nevertheless, the abstainers reported higher self-efficacy to abstain as compared to the students who reported being sexually active (Hotelling’s T = 0.729; F (5,251) = 36.602; p < 0.001) (Table 4). The abstainers reported a higher ability to resist all of the problematic situations that could encourage them to practice premarital sex (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Intention

The students' intentions to abstain from premarital sex were generally high. MANOVA showed a significant difference in overall intentions to abstain from sex until marriage, with higher intentions among the abstainers as compared to those who reported being sexually active (Hottelings T = 0.116; F (2,251) = 14.562; p < 0.001) (Table 4). The abstainers reported significantly higher intentions to continue to abstain from premarital sex during their university study (p < 0.001) and in the next year (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Discussion

This study aimed to identify the psychosocial determinants of premarital sexual practices among university students in Khartoum, using the I-Change Model as a theoretical framework. According to the findings of the analyses of variances, the students who reported being sexually active differed significantly from abstainers in having more knowledge about HIV/AIDS and a higher perception of susceptibility to HIV. They also reported significantly higher exposure to cues related to sexual activities and had a more positive attitude towards premarital sex. On the other hand, abstainers had a significantly more negative attitude towards premarital sex and higher self-efficacy to abstain from sex until marriage. Besides, they reported being more influenced by their peers' support and norms favouring abstinence from sex until marriage. These findings suggest that promoting abstinence from sex until marriage among university students in Sudan requires addressing these potential psychosocial determinants.

Regarding the pre-motivational determinants of premarital sex, sexual cues were significantly associated with sexual behaviours among the study population. The observed association between the exposure to specific sex cues, such as watching pornographic movies or videos and reading erotic stories and sexual practices, was reported by other previous cross-sectional studies as well (Akibu et al., 2017a, 2017b; Akter Hossen & Quddus, 2021; Bogale & Seme, 2014; Mulugeta & Berhane, 2014; Raheel et al., 2013). Nevertheless, longitudinal studies are needed to identify how reducing the exposure to these sex cues or mitigating their influence could influence students' sexual behaviours. This could inform future interventions and help design more effective programs aiming to delay sex and promote abstinence until marriage. In contrast to some previous studies' findings (Elshiekh et al., 2021; Muhammad et al., 2017; Odimegwu, 2005), this study found no association between religious cues, such as praying at the mosque and listening to religious lectures about abstinence, on the one hand and students' sexual abstinence at the other hand. However, this finding should be interpreted cautiously because praying at the mosque is a religious obligation and common practice in Sudan. Exposure to religious lectures advocating abstinence from extramarital sex is also widespread through both public and social media. Therefore, it is recommended to conduct further research to identify other influential religious cues, such as the frequency of religious attendance, which was previously identified as a significant predictor of sexual behaviour among college students (Lefkowitz et al., 2004; Penhollow et al., 2005). Besides, other factors such as the language and messages used by religious scholars could potentially affect the influence of their religious lectures on students' sexual behaviour; we did not measure this, which may be an area for further research. One potential reason for the low exposure and lack of association between HIV-related cues, such as knowing someone who died of AIDS, and sexual abstinence, could be the high level of stigma against PLWHA in Sudan, which prevents disclosure of HIV status (Mohamed & Mahfouz, 2013).

Concerning the motivational determinants and similar to previous research (Cha et al., 2007; Elshiekh et al., 2021; Rasberry & Goodson, 2009; Salameh et al., 2016), our study identified attitude towards premarital sex as an important determinant of sexual abstinence. The study findings also suggested that the students' perceptions of the social and legal consequences of practising sex before marriage, rather than health-associated consequences, could influence their decision to abstain from premarital sex. This could be explained by the highly conservative nature of the Muslim community in Sudan (Elshiekh et al., 2021). Hence, addressing this finding in future interventions aiming to promote sexual abstinence might be necessary. Besides, our study revealed an overall low perception of the negative impact of sexual activity on students' academic performance, although several previous studies identified this association (Lanari et al., 2020; Sabia & Rees, 2009; Schvaneveldt et al., 2001). Therefore, attempts to raise students' attention to this disadvantage may help promote sexual abstinence or delay sexual debut.

A recent qualitative study revealed that females had a more negative attitude toward premarital sex than male students due to the prevailing social norms that look at female virginity at marriage as a virtue (Elshiekh et al., 2021). This may also explain why significantly more female students reported being adherent to abstinence than male students in this study. The qualitative study also suggested that female students were more likely to practice sex for money than male students; in the same study, sexually active students reported a higher perception of the financial advantages of practising sex than their abstinent peers, suggesting that they have heard of or experienced financial advantages (Elshiekh et al., 2021). Therefore, further exploration of these gender-specific differences in attitude towards abstinence and premarital sex with a greater sample size may be needed.

Regarding social influence on university students' sexual behaviours, peer influences, including peer support, norms and modelling, were strongly associated with university students' sexual behaviour. This finding was also reported by several previous studies (Akter Hossen & Quddus, 2021; Mulugeta & Berhane, 2014; Tura et al., 2012). It implies that interventions seeking to promote abstinence from sex until marriage or delaying sex among university students may consider strategies that enhance favourable peer influence and mitigate peer pressure to practice sex. Considering the observed strong influence of peers, peer education interventions, which have been widely used to influence the sexual behaviours among youth (Medley et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2008), could be a suitable strategy for promoting abstinence from sex or delay sex among university students in Sudan. A previous review study of the effectiveness of these interventions for HIV prevention in developing countries pointed to the importance of considering factors that could increase their effectiveness. These included the proper selection of the peer educators, quality of peer educators' training and supervision, the compensation and retention of trained peer educators (Medley et al., 2009).

In addition, our study showed that community members, including parents, had less influence on students' sexual behaviours than peers did. Oppositely, previous studies among similar age groups in two sub-Saharan countries demonstrated parents and other family members' role in youth sexual abstinence and attitudes towards sex (Ajayi & Okeke, 2019; Alhassan & Dodoo, 2020). This contradiction could be attributed to cultural differences. Due to the Sudanese community's conservative nature and the prevailing norms that prohibit open discussion about sex, parents rarely engage in face-to-face interactions about sex-related issues with their sons and daughters (Elshiekh et al., 2021). A recent study among young adults in Malaysia has identified comfort, information and value as important family sexual communication dimensions associated with sexual behaviour and attitude. According to that study, these dimensions of family sexual communication are associated with delayed sexual initiation, safe sex behaviours and less open-minded sexual attitudes (Tan & Gun, 2018). Therefore, providing parents with accurate information about sex and teaching them how to communicate effectively with their sons and daughters about their sexual behaviours could be a valuable component of future interventions to delay sexual initiation and promote sexual abstinence among university students.

Likewise, religious leaders had no influential role in students' sexual behaviours in this study, although previous studies among African youth suggested the opposite (Somefun, 2019; Trinitapoli, 2009). However, our study assessed only the students' perceptions of their religious leaders' support and norms favouring abstinence from sex until marriage, which is considered a religious obligation. Besides, the denominational and individual differences between religious leaders and their approaches to addressing youth sexual behaviours could affect their influence (Trinitapoli, 2009; Ucheaga & Hartwig, 2010). In conclusion, further research is required to identify which roles and activities can be relevant for religious leaders in Sudan in promoting abstinence and delaying sexual onset to prevent HIV transmission (Trinitapoli, 2011a).

Self-efficacy to abstain from premarital sex was one of the important potential determinants of university students' sexual abstinence. A similar finding was reported by Cha et al. (2007), who identified abstinence self-efficacy as one of the predictors of the intention to abstain from premarital sex among Korean university students. In another study among 15–17 years old adolescents in Iran, students' self‐efficacy was also associated with their intention to remain sexually inactive (Mohtasham et al., 2009). A previous longitudinal study also concluded that to promote abstinence from premarital sex, interventions should not only increase self-efficacy to abstain at baseline but also lower its reduction over time by continuous boosting (Wang et al., 2009). However, this study was conducted among a younger age group and may not be generalizable to our study population. Therefore, replication of that study with university students may be recommended. Our study also revealed that the conditions challenging students' self-efficacy to abstain from sex are diverse. Several emotional factors could affect students' self-efficacy to abstain; however, the need for money and being challenged by sexually active peers have also been identified as difficult situations influencing students' self-efficacy. According to a recent qualitative study, the need for money as a barrier to sexual abstinence was reported by female students, while practising sex to prove adulthood in response to peers' challenges was reported by male students (Elshiekh et al., 2021). This implies that interventions aiming to enhance students' self-efficacy to abstain should be both comprehensive and tailored to address these diverse and gender-sensitive factors.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has focused mainly on the psychosocial determinants of premarital sexual behaviours among university students that have not been thoroughly investigated in Sudan before. Using the I-Change Model as a theoretical framework is one of the study`s strengths, as it facilitated the comprehensive exploration of premarital sex psychosocial determinants. In addition, using an online questionnaire encouraged many students to participate in this study and made it possible to collect sensitive data about their sexual practices and beliefs. However, the study sample size was relatively small and this prevented gender analysis of data that could identify some gender-specific determinants. Besides, some students were recruited through random sampling and others were recruited through snowball recruitment; therefore, the study sample may not be representative and its result may not be generalizable. In addition, being a cross-sectional study, a cause-effect relationship could not be inferred and further longitudinal studies may be needed to establish the causal associations between these psychosocial factors and the students' sexual behaviours. Furthermore, we did not assess factors pertaining to the action phase, such as action plans consisting of preparation plans and coping plans, which can be helpful in the translation of intention into behaviour (de Vries et al., 2006; Reinwand et al., 2016). Future research needs to identify which action plans may be helpful for our target population to translate their intentions into action. Despite these limitations, this study represents a valuable source of information for future HIV interventions in Sudan.

Conclusion

Exposure to certain cues, having a positive attitude towards premarital sex, peer influence and low self-efficacy were all associated with engaging in premarital sex. Considering the urgent need for comprehensive interventions to prevent HIV among university students in Sudan, and to promote abstinence from sex until marriage as a part of such interventions, addressing these potential determinants is crucial. However, other preventive strategies such as consistent condom use by sexually active students are to be promoted as well.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aarons, S. J., Jenkins, R. R., Raine, T. R., El-Khorazaty, M. N., Woodward, K. M., Williams, R. L., Clark, M. C., & Wingrove, B. K. (2000). Postponing sexual intercourse among urban junior high school students- a randomized controlled evaluation. Journal of Adolescent Health, 27(4), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00102-6

Abousselam, N., Naudé, L., Lens, W., & Esterhuyse, K. (2016). The relationship between future time perspective, self-efficacy and risky sexual behaviour in the Black youth of central South Africa. Journal of Mental Health, 25(2), 176–183. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1078884

Ajayi, A. I., & Okeke, S. R. (2019). Protective sexual behaviours among young adults in Nigeria: Influence of family support and living with both parents. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 983. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7310-3

Akeem, B. O. (2015). Principles and methods of validity and reliability testing of questionnaires used in social and health science researches. Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal, 22(4), 195–201. https://doi.org/10.4103/1117-1936.173959

Akibu, M., Gebresellasie, F., Zekarias, F., & Tsegaye, W. (2017a). Premarital sexual practice and its predictors among university students: Institution based cross sectional study. The Pan African Medical Journal, 28, 234. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2017.28.234.12125

Akibu, M., Gebresillasie, F., Zekarias, F., & Tsegaye, W. (2017b). Premarital sexual practice and its predictors among university students: Institution based cross sectional study. Pan African Medical Journal. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2017.28.234.12125

Akter Hossen, M., & Quddus, A. H. G. (2021). Prevalence and determinants of premarital sex among university students of bangladesh. Sexuality & Culture, 25(1), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09768-8

Alhassan, N., & Dodoo, F. N. (2020). Predictors of primary and secondary sexual abstinence among never-married youth in urban poor Accra,Ghana. Reproductive Health, 17(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-0885-4

Alo, C. (2016). Premarital sex, safer sex and factors influencing premarital sex practices among senior secondary school students in Ebonyi local government area of Ebonyi state Nigeria. Community Medicine & Public Health Care, 3, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.24966/CMPH-1978/100012

Beavers, A. S., Lounsbury, J. W., Richards, J. K., Huck, S. W., Skolits, G., & Esquivel, S. L. (2013). Practical considerations for using exploratory factor analysis in educational research. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 18, 1–13.

Bogale, A., & Seme, A. (2014). Premarital sexual practices and its predictors among in-school youths of shendi town, west Gojjam zone,North Western Ethiopia. Reproductive Health, 11(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-11-49

Brückner, H., & Bearman, P. (2005). After the promise: The STD consequences of adolescent virginity pledges. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36(4), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.01.005

Cha, E. S., Doswell, W. M., Kim, K. H., Charron-Prochownik, D., & Patrick, T. E. (2007). Evaluating the Theory of Planned Behavior to explain intention to engage in premarital sex amongst Korean college students: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(7), 1147–1157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.04.015

Chi, X., Yu, L., & Winter, S. (2012). Prevalence and correlates of sexual behaviors among university students: A study in Hefei, China. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 972. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-972

De Vries, H. (2017). An integrated approach for understanding health behavior. The I-Change Model as an Example., 2, 555585. https://doi.org/10.19080/PBSIJ.2017.02.555585

de Vries, H., Dijkstra, M., & Kuhlman, P. (1988). Self-efficacy: The third factor besides attitude and subjective norm as a predictor of behavioural intentions. Health Education Research, 3(3), 273–282. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/3.3.273

De Vries, H., Eggers, S. M., Jinabhai, C., Meyer-Weitz, A., Sathiparsad, R., & Taylor, M. (2014). Adolescents’ beliefs about forced sex in KwaZulu-Natal,South Africa. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(6), 1087–1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0280-8

de Vries, H., Mesters, I., Riet, J. V., Willems, K., & Reubsaet, A. (2006). Motives of Belgian adolescents for using sunscreen: The role of action plans. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 15(7), 1360–1366. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-05-0877

De Vries, H., Mesters, I., Steeg, H. V. D., & Honing, C. (2005). The general public`s information needs and perceptions regarding hereditary cancer: An application of the Integrated Change Model. Patient Education and Counseling, 56(2), 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2004.01.002

Dlamini, S., Taylor, M., Mkhize, N., Huver, R., Sathiparsad, R., de Vries, H., . . . Jinabhai, C. (2009). Gender factors associated with sexual abstinent behaviour of rural South African high school going youth in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Health Education Research, 24(3), 450-460. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyn041.

Dworkin, S. L., & Santelli, J. (2007). Do abstinence-plus interventions reduce sexual risk behavior among youth? PLoS Medicine, 4(9), e276. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040276

Eggers, S. M., Aaro, L. E., Bos, A. E., Mathews, C., Kaaya, S. F., Onya, H., & de Vries, H. (2016). Sociocognitive predictors of condom use and intentions among adolescents in three Sub-Saharan sites. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(2), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0525-1

Eggers, S. M., Mathews, C., Aarø, L. E., McClinton-Appollis, T., Bos, A. E. R., & de Vries, H. (2017). Predicting primary and secondary abstinence among adolescent boys and girls in the western cape, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 21(5), 1417–1428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1438-2

Elbadawi, A., & Mirghani, H. (2016). Assessment of HIV/AIDS comprehensive correct knowledge among Sudanese university: A cross-sectional analytic study 2014. The Pan African Medical Journal, 24, 48–48. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.24.48.8684

Elshiekh, H. F., de Vries, H., & Hoving, C. (2021). Assessing sexual practices and beliefs among university students in Khartoum, Sudan; a qualitative study. SHARA-J Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 18(1), 170–182.

Elshiekh, H. F., Hoving, C., & de Vries, H. (2020). Exploring determinants of condom use among university students in Sudan. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(4), 1379–1391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01564-2

Farrow, R., & Arnold, P. (2003). Changes in female student sexual Behaviour during the transition to university. Journal of Youth Studies, 6(4), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/1367626032000162087

Fearon, E., Wiggins, R. D., Pettifor, A. E., & Hargreaves, J. R. (2015). Is the sexual behaviour of young people in sub-Saharan Africa influenced by their peers? A systematic review. Social Science and Medicine, 146, 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.09.039

Ghebremichael, M. S., & Finkelman, M. D. (2013). The effect of premarital sex on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and high risk behaviors in women. Journal of AIDS and HIV Research, 5(2), 59–64.

Hedayati-Moghaddam, M. R., Eftekharzadeh-Mashhadi, I., Fathimoghadam, F., & Pourafzali, S. J. (2015). Sexual and reproductive behaviors among undergraduate university students in mashhad, a city in Northeast of Iran. Journal of Reproduction & Infertility, 16(1), 43–48. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25717435

Horanieh, N., Macdowall, W., & Wellings, K. (2020). Abstinence versus harm reduction approaches to sexual health education: Views of key stakeholders in Saudi Arabia. Sex Education, 20(4), 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2019.1669150

Idele, P., Madise, N., & Hinde, A. (2003). Perception of risk of HIV/AIDS and sexual behaviour in Kenya. Journal of Biosocial Science, 35, 385–411. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932003003857

Ismail, S. M., Kari, F., & Kamarulzaman, A. (2015). The Socioeconomic Implications among People Living with HIV/AIDS in Sudan: Challenges and Coping Strategies. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC), 16(5), 446–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325957415622449

Jemmott, J. B., III., Jemmott, L. S., & Fong, G. T. (1998). Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 279(19), 1529–1536.

Kamarulzaman, A. (2013). Fighting the HIV epidemic in the Islamic world. The Lancet, 381(9883), 2058–2060. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61033-8

Kandasamy, V., Hirai, A. H., Kogan, M. D., Lawler, M., & Volpe, E. (2018). Title V maternal and child health services block grant priority needs and linked performance measures: current patterns and trends (2000–2015). Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(12), 1725–1737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2568-0

Kantor, L. M., Santelli, J. S., Teitler, J., & Balmer, R. (2008). Abstinence-only policies and programs: An overview. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 5(3), 6. https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2008.5.3.6

Khalajabadi Farahani, F., Akhondi, M. M., Shirzad, M., & Azin, A. (2018). HIV/STI risk-taking sexual behaviours and risk perception among male university students in Tehran: Implications for HIV Prevention Among Youth. Journal of Biosocial Science, 50(1), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021932017000049

Kirby, D. B., Laris, B. A., & Rolleri, L. A. (2007). Sex and HIV education programs: Their impact on sexual behaviors of young people throughout the world. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(3), 206–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.143

Kohler, P. K., Manhart, L. E., & Lafferty, W. E. (2008). Abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education and the initiation of sexual activity and teen pregnancy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(4), 344–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.026

Lanari, D., Mangiavacchi, L., & Pasqualini, M. (2020). Adolescent sexual behaviour and academic performance of Italian students. Genus, 76(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-020-00093-4

Lefkowitz, E. S., Gillen, M. M., Shearer, C. L., & Boone, T. L. (2004). Religiosity, sexual behaviors, and sexual attitudes during emerging adulthood. The Journal of Sex Research, 41(2), 150–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490409552223

Majer, M., Puškarić Saić, B., Musil, V., Mužić, R., Pjevač, N., & Jureša, V. (2019). Sexual behaviour and attitudes among university students in Zagreb. European Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz186.164

Marston, C., & King, E. (2006). Factors that shape young people’s sexual behaviour: A systematic review. The Lancet, 368(9547), 1581–1586. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69662-1

Massad, S. G., Karam, R., Brown, R., Glick, P., Shaheen, M., Linnemayr, S., & Khammash, U. (2014). Perceptions of sexual risk behavior among Palestinian youth in the West Bank: A qualitative investigation. BMC Public Health, 14, 1213. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1213

Maulana, A. O., Krumeich, A., & Van Den Borne, B. (2009). Emerging discourse: Islamic teaching in HIV prevention in Kenya. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 11(5), 559–569. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27784476

Medley, A., Kennedy, C., O’Reilly, K., & Sweat, M. (2009). Effectiveness of peer education interventions for HIV prevention in developing countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Education and Prevention : Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 21(3), 181–206. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3.181

Miller, A. N., Mutungi, M., Facchini, E., Barasa, B., Ondieki, W., & Warria, C. (2008). An outcome assessment of an ABC-based HIV peer education intervention among Kenyan university students. Journal of Health Communication, 13(4), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730802063470

Mohamed, B. (2014). Correlates of condom use among males in North Sudan. Sexual Health. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH13090

Mohamed, B. A., & Mahfouz, M. S. (2013). Factors associated with HIV/AIDS in Sudan. BioMed Research International, 2013, 971203–971203. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/971203

Mohtasham, G., Shamsaddin, N., Bazargan, M., Anosheravan, K., Elaheh, M., & Fazlolah, G. (2009). Correlates of the intention to remain sexually inactive among male adolescents in an Islamic country: Case of the Republic of Iran. Journal of School Health, 79(3), 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.0396.x

Muhammad, N. A., Shamsuddin, K., Sulaiman, Z., Amin, R. M., & Omar, K. (2017). Role of religion in preventing youth sexual activity in Malaysia: A mixed methods study. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(6), 1916–1929. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0185-z

Mulugeta, Y., & Berhane, Y. (2014). Factors associated with pre-marital sexual debut among unmarried high school female students in bahir Dar town, Ethiopia: Cross-sectional study. Reproductive Health, 11, 40–40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-11-40

O'Donnell, L., Stueve, A., O'Donnell, C., Duran, R., San Doval, A., Wilson, R. F., . . . Pleck, J. H. (2002). Long-term reductions in sexual initiation and sexual activity among urban middle schoolers in the reach for health service learning program. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(1), 93-100.

Odimegwu, C. (2005). Influence of Religion on Adolescent Sexual Attitudes and Behaviour among Nigerian University Students: Affiliation or Commitment? African Journal of Reproductive Health / La Revue Africaine De La Santé Reproductive, 9(2), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.2307/3583469

Omoteso, B. A. (2006). A study of the sexual behaviour of university undergraduate students in Southwestern Nigeria. Journal of Social Sciences, 12(2), 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2006.11978380

Penhollow, T., Young, M., & Denny, G. (2005). The Impact of Religiosity on the Sexual Behaviors of College Students. American Journal of Health Education, 36(2), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2005.10608163

Raheel, H., Mahmood, M. A., & BinSaeed, A. (2013). Sexual practices of young educated men: Implications for further research and health education in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Journal of Public Health (oxford, England), 35(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds055

Rasberry, C. N., & Goodson, P. (2009). Predictors of secondary abstinence in U.S. college undergraduates. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(1), 74–86.

Raymond, M., Bogdanovich, L., Brahmi, D., Cardinal, L. J., Fager, G. L., Frattarelli, L. C., Hecker, G., Jarpe, E. A., Viera, A., Kantor, L. M., & Santelli, J. S. (2008). State refusal of federal funding for abstinence-only programs. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 5(3), 44. https://doi.org/10.1525/srsp.2008.5.3.44

Reinwand, D. A., Crutzen, R., Storm, V., Wienert, J., Kuhlmann, T., de Vries, H., & Lippke, S. (2016). Generating and predicting high quality action plans to facilitate physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption: Results from an experimental arm of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 16, 317. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2975-3

Rubens, M., Batra, A., Sebekos, E., Tanaka, H., Gabbidon, K., & Darrow, W. (2019). Exploring the determinants of risky sexual behavior among ethnically diverse university students: The student behavioral health survey-web. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 6(5), 953–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00596-7

Sabia, J. J., & Rees, D. I. (2009). The effect of sexual abstinence on females’ educational attainment. Demography, 46(4), 695–715. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0072

Salameh, P., Zeenny, R., Salamé, J., Waked, M., Barbour, B., Zeidan, N., & Baldi, I. (2016). Attitudes towards and practice of sexuality among university students in Lebanon. Journal of Biosocial Science, 48(2), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932015000139

Santelli, J. S., Kaiser, J., Hirsch, L., Radosh, A., Simkin, L., & Middlestadt, S. (2004). Initiation of sexual intercourse among middle school adolescents: The influence of psychosocial factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34(3), 200–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.06.004

Santelli, J. S., Kantor, L. M., Grilo, S. A., Speizer, I. S., Lindberg, L. D., Heitel, J., Schalet, A. T., Lyon, M. E., Mason-Jones, A. J., McGovern, T., Heck, C. J., Rogers, J., & Ott, M. A. (2017). Abstinence-only-until-marriage: an updated review of us policies and programs and their impact. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(3), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.031

Schvaneveldt, P. L., Miller, B. C., Berry, E. H., & Lee, T. R. (2001). Academic goals, achievement, and age at first sexual intercourse: Longitudinal, bidirectional influences. Adolescence, 36(144), 767–787.

Shakiba, E., Ramazani, U., Mardani, E., Rahimi, Z., Nazar, Z. M., Najafi, F., & Moradinazar, M. (2021). Epidemiological features of HIV/AIDS in the Middle East and North Africa from 1990 to 2017. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 32(3), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462420960632

Somefun, O. D. (2019). Religiosity and sexual abstinence among Nigerian youths: Does parent religion matter? BMC Public Health, 19(1), 416. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6732-2

Sychareun, V., Thomsen, S., Chaleunvong, K., & Faxelid, E. (2013). Risk perceptions of STIs/HIV and sexual risk behaviours among sexually experienced adolescents in the Northern part of Lao PDR. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1126. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1126

Taffa, N., Klepp, K. I., Sundby, J., & Bjune, G. (2002). Psychosocial determinants of sexual activity and condom use intention among youth in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 13(10), 714–719. https://doi.org/10.1258/095646202760326480

Tan, A. J., & Gun, C. H. (2018). Let’s talk about sex: family communication predicting sexual attitude, sexual experience, and safe sex behaviors in Malaysia. International Journal of Sexual Health, 30(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2018.1470592

Trinitapoli, J. (2009). Religious teachings and influences on the ABCs of HIV prevention in Malawi. Social Science and Medicine, 69(2), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.018

Trinitapoli, J. (2011a). The AIDS-related activities of religious leaders in Malawi. Global Public Health, 6(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2010.486764

Tura, G., Alemseged, F., & Dejene, S. (2012). Risky Sexual Behavior and Predisposing Factors among Students of Jimma University, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences, 22(3), 170–180. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3511895/

Ucheaga, D. N., & Hartwig, K. A. (2010). Religious leaders’ response to AIDS in Nigeria. Global Public Health, 5(6), 611–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441690903463619

Uecker, J. E. (2015). Social context and sexual intercourse among first-year students at selective colleges and universities in the United States. Social Science Research, 52, 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.01.005

UNAIDS. (2019). Country progress report -Sudan Global AIDS Monitoring 2019 Available online at https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3801751 [verified 20 Oct 2020].

UNAIDS. (2020a). AIDSinfo, Indicators. https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/. Accessed on 20/10/2020a.

UNAIDS. (2020b). Country progress report -Sudan Global AIDS Monitoring 2020b Available online at https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/SDN_2020b_countryreport.pdf [verified 20 Jun 2022].

Underhill, K., Montgomery, P., & Operario, D. (2007a). Sexual abstinence only programmes to prevent HIV infection in high income countries: Systematic review. BMJ (clinical Research Ed.), 335(7613), 248–248. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39245.446586.BE

Underhill, K., Montgomery, P., & Operario, D. (2008). Abstinence-plus programs for HIV infection prevention in high-income countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.Cd007006

Underhill, K., Operario, D., & Montgomery, P. (2007b). Systematic Review of Abstinence-Plus HIV Prevention Programs in High-Income Countries. PLOS Medicine, 4(9), e275. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040275

Wang, R.-H., Cheng, C.-P., & Chou, F.-H. (2009). Predictors of sexual abstinence behaviour in Taiwanese adolescents: A longitudinal application of the transtheoretical model. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(7), 1010–1017. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02509.x

Wetherill, R. R., Neal, D. J., & Fromme, K. (2010). Parents, Peers, and Sexual Values Influence Sexual Behavior During the Transition to College. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(3), 682–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9476-8

Willems, R. (2009). The importance of interdisciplinary collaborative research in responding to HIV/AIDS vulnerability in rural Senegal. African Journal of AIDS Research, 8(4), 433–442. https://doi.org/10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.4.7.1044

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the university students who participated in this study, the university administrations who allowed the study to be done in their universities and the VCT counsellors for their assistance in data collection. We also thank the Sudan National AIDS control program officers in Khartoum state for their support.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity or not-for-profit organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Directorate of Research, MOH, Khartoum State in July 2017. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Informed Consent

This was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All participants were informed that their participation in the study was voluntary and they had the right to withdraw without any consequences. They were also informed that their names, addresses, phone numbers, or universities were not included in the questionnaire to maintain their privacy and confidentiality.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elshiekh, H.F., Hoving, C. & de Vries, H. Psychosocial Determinants of Premarital Sexual Practices among University Students in Sudan. Sexuality & Culture 27, 78–103 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-022-10004-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-022-10004-8