Abstract

The pathology of poorly differentiated sinonasal malignancies has been the subject of extensive studies during the last decade, which resulted into significant developments in the definitions and histo-/pathogenetic classification of several entities included in the historical spectrum of “sinonasal undifferentiated carcinomas (SNUC)” and poorly differentiated unclassified carcinomas. In particular, genetic defects leading to inactivation of different protein subunits in the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex have continuously emerged as the major (frequently the only) genetic player driving different types of sinonasal carcinomas. The latter display distinctive demographic, phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. To date, four different SWI/SNF-driven sinonasal tumor types have been recognized: SMARCB1(INI1)-deficient carcinoma (showing frequently non-descript basaloid, and less frequently eosinophilic, oncocytoid or rhabdoid undifferentiated morphology), SMARCB1-deficient adenocarcinomas (showing variable gland formation or yolk sac-like morphology), SMARCA4-deficient carcinoma (lacking any differentiation markers and variably overlapping with large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and SNUC), and lastly, SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal teratocarcinosarcoma. These different tumor types display highly variable immunophenotypes with SMARCB1-deficient carcinomas showing variable squamous immunophenotype, while their SMARCA4-related counterparts lack such features altogether. While sharing same genetic defect, convincing evidence is still lacking that SMARCA4-deficient carcinoma and SMARCA4-deficient teratocracinosarcoma might belong to the spectrum of same entity. Available molecular studies revealed no additional drivers in these entities, confirming the central role of SWI/SNF deficiency as the sole driver genetic event in these aggressive malignancies. Notably, all studied cases lacked oncogenic IDH2 mutations characteristic of genuine SNUC. Identification and precise classification of these entities and separating them from SNUC, NUT carcinoma and other poorly differentiated neoplasms of epithelial melanocytic, hematolymphoid or mesenchymal origin is mandatory for appropriate prognostication and tailored therapies. Moreover, drugs targeting the SWI/SNF vulnerabilities are emerging in clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The chromatin remodeling Switch/ Sucrose non-fermentable (SWI/SNF) complex is a highly conserved complex of >20 genes mapped to different chromosomal regions [1]. While the precise function of this complex is still largely unknown, its role in remodeling the chromatin, and hence, regulating the processes of gene expression and cell differentiation has been widely appreciated [1]. In general, the different SWI/SNF complex components function as tumor suppressors [1]. Accordingly, it is inactivating mutations leading to loss of protein function and gene deletions that are responsible for tumor initiation in the SWI/SNF-driven entities [1]. Additional potential mechanisms of SWI/SNF inactivation include epigenetic mechanisms as well. With few exceptions, SWI/SNF inactivating gene abnormalities lead to universal loss of the respective protein of the subunit affected by the genetic alternation, irrespective of the type of gene defect. This, together with the ever-emerging commercially available specific antibodies against different SWI/SNF proteins, made the SWI/SNF immunohistochemistry a powerful tool in identifying and classifying SWI/SNF-driven neoplasms [2,3,4,5].

Remarkably, there seems to be a striking organ-specific clustering of mutations in certain SWI/SNF genes, so that ARID1A mutations prevail in genital tract malignancies while SMARCB1 and SMARCA4 mutations predominate among SWI/SNF-driven neoplasms of soft tissue and lung, respectively [5]. In the sinonasal tract, to date only SMARCB1 (INI1) and SMARCA4 have been recurrently associated with specific tumor types. This highly selective phenomenon might reflect the diverse SWI/SNF assembly variants found in the stem cells and their progenitors in different organs [6]. This review summarizes the pertinent clinicopathological features of those recently described SWI/SNF-related sinonasal neoplasms that are planned to be included in the upcoming WHO classification.

SMARCB1-Deficient Sinonasal Carcinoma

SMARCB1, mapped to chromosomal region 22q11.2, is a core subunit of the SWI/SNF complex [2]. Like other tumor suppressor proteins, SMARCB1 is globally expressed in the nuclei of all human cell types [2,3,4,5]. Loss of SMARCB1 because of biallelic inactivation of its gene in a subset of poorly or undifferentiated sinonasal carcinoma has been first described in 2014 by two independent groups, followed by a few additional series including one large multi-institutional series (n=39) [7, 8]. To date, <150 cases have been reported [7,8,9,10,11,12].

These tumors show a slight predominance of males with a mean age of 52 years (range, 19 to 89). They present as locally advanced disease (mostly T4). The paranasal sinuses, mainly the ethmoids, are involved in majority of cases with variable involvement of the nasal cavity. The disease follows an aggressive clinical course resulting in death of 56% of patients at a median interval of 16 months [10]. Only one third of patients were alive without disease at last follow-up [10].

Like most other SMARCB1-deficient neoplasms, the tumors display a monomorphic cytology lacking significant pleomorphisms or bizarre-looking nuclei. Majority of cases (60%) show a predominance of basaloid morphology, occasionally indistinguishable from non-keratinizing poorly differentiated basaloid squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). However, frankly squamous cell features and keratinization are absent. A smaller fraction of cases (30%) displays a “pinkish” eosinophilic, plasmacytoid/rhabdoid cell morphology [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Scattered plasmacytoid and rhabdoid cells can be identified, also in the basaloid tumors, upon scrutiny [25]. Although focal glandular differentiation was mentioned in a few cases in the initial studies, tumors featuring prominent gland formation have been later redefined as adenocarcinomas (see section on adenocarcinoma below). A few cases contain limited foci of clear cells. Spindle cell “sarcomatoid” pattern is rare. No conventional surface dysplasia or carcinoma in situ have been observed, but a variable degree of surface pagetoid spread (occasionally mimicking in situ carcinoma) may be seen [7, 8, 10]. Representative examples of the common and variant features of these tumors are depicted in Figs. 1 and 2.

Representative examples of SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinoma. A basaloid (dark-stained) monomorphic cells replacing the surface epithelium and showing extensive downgrowth along preexisting glands resulting in combined exophytic-endophytic papillary pattern at low-power. B monomorphic basaloid cell morphology with prominent stromal desmoplasia. C numerous rhabdoid cells are interspersed among undifferentiated basaloid cells. D replacement of the surface mucosa by tumor tissue mimicking carcinoma in situ. E partial downgrowth along deeper respiratory glands. F complete loss of SMARCB1 is definitional for these tumors

Representative examples of uncommon features in SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinoma. A eosinophilic (pinkish) cells forming prominent variably sized cellular nests. B lymph node metastasis of an eosinophilic tumor showing compact nests, superficially reminiscent of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma or apocrine salivary duct carcinoma. Rarely, smudgy bizarre looking cells (C) and clear cells (D) are seen

By immunohistochemistry, SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinomas express uniformly pankeratins (97%) and variably CK5 (64%), p63 (55%) and CK7 (48%) [10]. They are negative for high-risk Human Papillomavirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and NUT [7, 8, 10]. Like SWI/SNF-deficient neoplasms in different organs, SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinoma may show focal immunoreactivity for different neuroendocrine markers [10, 13]. SMARCB1 loss is definitional. Rare co-loss of SMARCA2 but not SMARCA4 or ARID1A may be observed [10]. Biallelic (homozygous) or monoallelic (heterozygous) deletions affecting the SMARCB1 gene locus are detectable by FISH in majority of cases [8, 10]. Although no detailed prospective studies on histology-tailored therapy for this tumor type are available, an exaggerated response to platinum-based chemotherapy has been observed in anecdotal cases, indicating the need to recognize these tumors correctly, so that their most suitable therapeutic strategies can be assessed reliably in the future [7, 10]. Cases tested with larger gene panels revealed no additional driver mutations, in particular, IDH2 mutations were absent underlining their distinctness from SNUC [14, 15].

Differential Diagnosis

Based on histological pattern, SMARCB1-deficient carcinoma has been previously likely included in the historical spectrum of SNUC, basaloid nonkeratinizing SCC or myoepithelial carcinoma. Its distinction from other epithelial and mesenchymal basaloid neoplasms is based on combined sets of clinicopathological and genotypic features (Table 1). Rare myoepithelial carcinomas with rhabdoid features may display SMARCB1 loss and, when presenting in the sinonasal tact, may mimic SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinomas [16]. The latter however do not express myoepithelial markers such as S100, SOX10, calponin, smooth muscle actin and others.

SMARCB1-deficient Sinonasal Adenocarcinoma

This rare variant in the spectrum of SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinoma is defined by presence of unequivocal gland formation [17]. To date, <20 cases have been described [17, 18]. A higher predilection for males (5:1) is observed compared to non-glandular SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal carcinomas. Both undifferentiated and gland-forming tumor types present at a comparable median age (52 versus 57 years; range, 19 to 89 versus 21 to 82, respectively). The nasal cavity represents the major site affected with some tumors involving multiple sinonasal sites. Selective involvement of the ethmoid or the maxillary sinuses is less common.

Histologically, these tumors feature a predominance of oncocytoid/plasmacytoid cell morphology with variable, but unequivocal gland formation characterized by presence of tubules, cribriforming, intracellular and/or luminal mucin and foci with yolk sac tumor-like features [17, 18]. The latter may closely resemble the pattern of secretory endometrium seen in gonadal yolk sac tumors. The sieve-like reticular/ microcystic yolk sac pattern may be predominant and rarely represent the sole pattern seen throughout the tumor [18,19,20]. This variant can be diagnostically challenging if one is not aware of it. The neoplastic cells usually display uniformly high-grade cytology with brisk mitotic activity and frequent foci of necrosis, but rare cases may show a deceptively bland-looking histology.

In contrast to the non-glandular SMARCB1-deficient carcinomas, this variant displays more extensive and frequent expression of CK7 (83%) than p40 (33%), [17]. Variable reactivity is observed for glypican-3 (90%), SALL4 (50%), HepPar-1 (50%), CDX2 (27%) CK20 (25%), PLAP (11%) and AFP (10%), irrespective of present or absent yolk sac-like features [17]. Representative examples of the common and variant features of these tumors are depicted in Fig. 3.

Representative examples of SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal adenocarcinoma. A variable admixture of glands, sieve-like pattern or pseudocribriform structures embedded within abundant mucoid stroma, note uniformly high-grade cytology. B some tumors display pure yolk sac-like morphology with bland-looking cells. C this predominantly solid tumor shows numerous mini-lumina and large eosinophilic cells, highly reminiscent of apocrine salivary duct carcinoma and high-grade non-intestinal adenocarcinoma. D transition from adenocarcinoma (left) to solid undifferentiated component (right) may be seen. E strong diffuse reactivity with SALL4 combined with pure yolk sac-like pattern, as in this case, represents a major pitfall. F complete loss of SMARCB1 is limited to the neoplastic cells

Differential Diagnosis

SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal adenocarcinoma needs to be distinguished from several mimics including mainly high-grade intestinal and non-intestinal adenocarcinoma, as well as myoepithelial carcinoma, primary and metastatic yolk sac tumor, and metastatic hepatoid adenocarcinoma from the digestive system and other sites.

SMARCA4-deficient Sinonasal Carcinoma

The catalytic SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex subunit SMARCA4 (BRG1) is mapped to chromosomal region 19p13.2 [1]. Like SMARCB1, it is also involved in the regulation of gene transcription, and it hence regulates cell differentiation. Inactivating (either sporadic or germline) SMARCA4 mutations have emerged as a defining marker for a plethora of highly aggressive malignancies unified by large undifferentiated epithelioid or rhabdoid cells and occurring across different organs (ovary, uterus, mediastinum, lung, digestive tract, and others) [21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Initially reported as rare alternative mechanism in a rare subset of SMARCB1-proficient sinonasal carcinomas [28], SMARCA4 inactivation has latter been recognized as a defining marker for a distinctive subset of aggressive sinonasal epithelial neoplasms characterized by similar morphology as SMARCA4-deficient malignancies in other organs. Uniformity of cytology and keratin expression justified classifying these rare malignancies in the sinonasal tract as carcinomas and not sarcomas. Indeed, the prototypical SMARCA4-deficient thoracomediastinal malignancies (initially considered sarcomas [22]) have been redefined as undifferentiated carcinoma type based on several demographic and clinicopathological characteristics [29]. To date, a total of 22 cases have been reported [28, 30,31,32,33]. SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinomas represented 4% of poorly differentiated/undifferentiated epithelial-derived sinonasal malignancies [33], 9% of all SNUCs, and 20% of IDH2-wildtype SNUC [30]. Their demographic and clinical features are similar to their SMARCB1-deficient counterparts, but with a striking predilection for men and a lower median age (35–44 vs. 57 years; range, 20–70) [32, 33]. Most tumors originate in the nasal cavity or involve multiple sinonasal sites. In contrast to SMARCB1-deficient carcinomas, and because of their cell morphology and immunophenotype, most SMARCA4-deficient tumors have been initially misclassified as small or large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas and, less frequently, as SNUC or teratocarcinosarcoma [32, 33].

Histologically, sheets of large epithelioid anaplastic cells predominate with variable nesting or trabecular pattern mimicking SNUC. This pattern recapitulates the pattern seen in SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated malignancies of the thorax, ovary, and other visceral organs [21,22,23,24]. Contrasting with their SMARCB1-deficient counterparts, the basaloid small cell pattern is much infrequent in SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinomas. Rhabdoid cells are uncommon but may rarely predominate. Brisk mitotic activity and extensive foci of necrosis are commonly seen. SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinomas lack differentiated features, both histologically (absence of glands, squamous cells, and others) and immunohistochemically (lack of squamous cell marker expression) [32, 33].

Abortive neuroendocrine-like rosettes are seen in rare cases. Immunohistochemistry confirms lack of differentiation (consistently positive for pankeratin and rarely CK7 but negative with CK5, p63, p40, p16 and NUT). Notably, variable (mostly focal and weak) reactivity with the neuroendocrine markers is seen including synaptophysin (90%), chromogranin-A (40%) and CD56 (60%) [32]. Rare cases display olfactory-like immunophenotypic features at the periphery of the neoplastic lobules suggesting abortive hybrid differentiation [32]. Global loss of SMARCA4, restricted to the neoplastic cells, is definitional in all cases. Rare cases may show co-loss of SMARCA2 [32]. Retained expression of SMARCB1/INI1 is seen in all cases. Representative examples of the common and variant features of these tumors are depicted in Fig. 4.

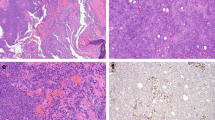

Representative examples of SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma. A SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma show a predominance of large undifferentiated cells with variable lobular pattern mimicking SNUC and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. B cytological uniformity with variably prominent nuclei and brisk mitotic activity. C rarely, abrupt transition from large cell (right) to blue-stained ovoid cells mimicking small cell carcinoma (left) is seen; note foci of necrosis on right. D main image: calretinin as well as synaptophysin (not shown) are expressed at the periphery of the cell aggregates suggesting hybrid olfactory-like features. D subimage: complete loss of SMARCA4 is the defining feature of these tumors

SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma behaves more aggressively compared to the SMARCB1-deficient tumors; two thirds of patients with follow-up died of their disease within one year [32, 33].

Differential Diagnosis

NUT carcinoma (mainly the undifferentiated large or small cell pattern), neuroendocrine carcinomas (including small and large cell types) and Hyams grade 4 olfactory neuroblastoma are the major considerations [34, 35]. Lack of p40 expression is observed in a small subset of NUT carcinoma and is thus not reliable to rule out NUT carcinoma, making the NUT immunohistochemistry mandatory in this differential. In most cases, SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma lacks the classical nuclear and chromatin characteristics of true neuroendocrine carcinomas, but they display frequently focal or diffuse but usually weak and heterogeneous expression of the neuroendocrine markers [32]. Diffuse expression of keratins, lack of classical neuroendocrine features, and absence of uniform reactivity for neuroendocrine markers exclude the possibility of olfactory neuroblastoma. As pointed out above, a rare subset of tumors tends to display olfactory-type differentiation limited to the periphery of the neoplastic nests and lobules with coexpression of neuroendocrine markers and calretinin. In contrast to genuine SNUC, all cases tested to date have been negative for IDH2 mutations [15, 30, 32, 33].

SMARCA4-deficient Sinonasal Teratocarcinosarcoma

Teratocarcinosarcoma (TCS) is a rare and highly aggressive malignancy that is virtually confined to the sinonasal tract and has not been reported to occur in other organs. It is defined by a triphasic growth combining teratoma-like, carcinoma-like, and sarcomatous stromal/mesenchymal elements with highly varying neuroectodermal-like components [36]. Several histogenetic theories have been raised to explain their varied multiphenotypic histology including a “germ cell origin”, hence the original name “malignant teratoma” [36]. However, recent developments have shed more light on the molecular pathogenesis and histogenesis of different multiphenotypic tumors, historically considered variants of primitive germ cell neoplasms and referred to by the name “malignant teratoma”. Notably, so-called malignant teratoma of the thyroid has been redefined recently as DICER1-associated somatic malignancy of adults, unrelated to genuine germ cell neoplasia [37, 38]. Likewise, identification of inactivating biallelic SMARCA4 mutations in the vast majority of sinonasal TCS confirmed the notion that these malignancies are of epithelial somatic origin and are not related to germ cell lineage too [39].

Sinonasal TCSs are exceptionally rare. To date, ~ 130 cases have been reported: mostly as single case reports or small series [36, 39,40,41]. Like SMARCA4-deficient carcinomas, they predominantly originate in the nasal cavity (up to 79% of cases) with a striking male predominance (83%) and a wide age range (mean: 50 years; range 10–82) [36, 39]. Most tumors present as large locally advanced masses (mean size: 7.4 cm) involving multiple sinonasal sites and invading the skull base. Only one third of patients remained disease-free after surgery and multimodal therapy, the remainder had either persistent local disease, local recurrence, distant metastases or have died [39]. In a recent systematic survival analysis review, the mean survival at 2 years was 55% [41].

Histologically, most TCSs demonstrated a predominance of undifferentiated primitive neuroepithelial elements with variable foci of neuropil-like matrix and rosettes. The epithelial component was mainly represented by immature clear cell (fetal-type) squamous islands but occasionally shows more mature-looking keratinizing epithelium. A glandular component with mucinous, intestinal-type or ciliated respiratory epithelium is frequently seen, but to a highly variable extent. The stromal mesenchymal component varies greatly as well from undifferentiated fibroblastic-type stromal elements (occasionally with periglandular condensation) to prominent rhabdomyoblastic features with strap cells. Less common stromal elements include foci of cartilage and bone.

The immunophenotype of the neoplastic cells in TCS corresponds to the line of differentiation of the diverse elements within a given tumor and is hence not specific, except for highlighting subtle components. Recently, our group have reported loss of SMARCA4 expression as the driver (sole molecular abnormality) in 82% of sinonasal TCSs by immunohistochemistry [39]. SMARCA4 loss was global across all tumor components in 68% and heterogeneous in 14% of cases. Cases with heterogeneous expression revealed SMARCA4 loss in the stromal elements but reduced or weak reactivity in the epithelial and the neuroepithelial components.

SMARCB1 expression is essentially intact, although a few cases may display variable low reactivity, but none showed complete loss of this protein [39]. Partial loss of SMARCA2 is a frequent finding in most tumors. Representative examples of the common and variant features of these tumors are depicted in Figs. 5 and 6.

Representative examples of sinonasal teratocarcinosarcoma. A disordered admixture of mucinous glands, cohesive larger basaloid cell aggregates and primitive neuroectodermal-like stroma. B clear cell fetal-type tubules embedded within cellular primitive stroma. C clear cell fetal-type squamous islands (mid upper field) and scattered neuroepithelial rosettes (right) surrounded by highly cellular primitive stroma. D cellular spindled sarcomatoid stroma with numerous rhabdomyoblasts. E SMARCA4 loss is observed in stroma and in the glands. F mature-looking bland paucicellular stroma also shows SMARCA4 loss indicating it is neoplastic

Further examples of sinonasal teratocarcinosarcoma. Some tumors display numerous organoid cellular “balls” (A) composed of centrally located dilated mucous glands surrounded by condensed primitive neuroectodermal-type stroma (B) highlighted by synaptophysin (C) and calretinin (D) and an outermost thin layer of primitive mesenchyme highlighted by desmin-immunostaining (E). F SMARCA4 loss is observed in all three cellular compartments

Differential Diagnosis and Conceptual Reappraisal of TCS

Remarkably, and due to their highly heterogeneous morphological patterns, sinonasal TCS may show significant overlap with almost any entity in the spectrum of poorly differentiated and undifferentiated malignancies, especially on limited biopsy material [14]. Accordingly, several entities such as olfactory neuroblastoma, poorly differentiated rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, high-grade non-intestinal adenocarcinoma, intestinal-type adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, teratoma, odontogenic carcinosarcoma, and many others may be considered upon initial assessment of limited biopsy material. Predominance of one or the other component in different biopsies or in primary versus recurrent tumors should not be misinterpreted as discrepancy. SMARCA4-deficient carcinoma is the major consideration if SMARCA4 loss is identified in biopsies. Being unified by SMARCA4 loss, TCS and SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma might be looked at as different morphotypes on the spectrum of same entity rather than two independent entities [32, 39]. However, in the experience of the author, rarity of carcinoma-like large cell components/ foci in majority of TCS argues to the contrary. It is the small blue cell (olfactory-like) pattern in the spectrum of SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma that might be indistinguishable from TCS on limited biopsy material. In such a scenario, a descriptive diagnosis of “SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal malignancy consistent with either carcinoma or TCS” can be made prior to resection. Rarely, metastatic SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated thoracopulmonary malignancies (indistinguishable from SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma) might present in the head and neck sites, although very rare in the sinonasal areas, and should be thought of. Exploring the recent clinical history and review of current chest imaging are diagnostic [42].

The molecular pathogenesis of the small subset of SMARCA4-proficient TCS remains unknown. The role of CTNNB1 mutations detected in some cases merits further investigation [43, 44].

Therapeutic Implications of SWI/SNF Deficiency

Although no specific therapy exists for these aggressive neoplasms yet, current data suggests emerging roles for therapeutic opportunities targeting EZH2, CDK4/6 inhibitors and other potential targets in the treatment of these lethal diseases in clinical trials [45, 46]. Moreover, compiling evidence is accumulating that subsets of SWI/SNF-deficient malignancies may show enhanced response to immune therapies [47].

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Wang X, Haswell JR, Roberts CW. Molecular pathways: SWI/SNF (BAF) complexes are frequently mutated in cancer--mechanisms and potential therapeutic insights. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:21–7.

Judkins AR. Immunohistochemistry of INI1 expression: a new tool for old challenges in CNS and soft tissue pathology. Adv Anat Pathol. 2007;14:335–9.

Hollmann TJ, Hornick JL. INI1-deficient tumors: diagnostic features and molecular genetics. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:e47–63.

Agaimy A. The expanding family of SMARCB1(INI1)-deficient neoplasia: implications of phenotypic, biological, and molecular heterogeneity. Agaimy A. Adv Anat Pathol. 2014;21:394–410.

Agaimy A. SWI/SNF complex-deficient soft tissue neoplasms: a pattern-based approach to diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019;12:149–63.

Kadoch C, Crabtree GR. Mammalian SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes and cancer: Mechanistic insights gained from human genomics. Sci Adv. 2015 Jun 12;1(5):e1500447.

Agaimy A, Koch M, Lell M, Semrau S, Dudek W, Wachter DL, Knöll A, Iro H, Haller F, Hartmann A. SMARCB1(INI1)-deficient sinonasal basaloid carcinoma: a novel member of the expanding family of SMARCB1-deficient neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1274–81.

Bishop JA, Antonescu CR, Westra WH. SMARCB1 (INI-1)-deficient carcinomas of the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1282–9.

Bell D, Hanna EY, Agaimy A, Weissferdt A. Reappraisal of sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: SMARCB1 (INI1)-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: a single-institution experience. Virchows Arch. 2015;467:649–56.

Agaimy A, Hartmann A, Antonescu CR, Chiosea SI, El-Mofty SK, Geddert H, Iro H, Lewis JS Jr, Märkl B, Mills SE, Riener MO, Robertson T, Sandison A, Semrau S, Simpson RH, Stelow E, Westra WH, Bishop JA. SMARCB1 (INI-1)-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: a series of 39 cases expanding the morphologic and clinicopathologic spectrum of a recently described entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:458–71.

Kakkar A, Antony VM, Pramanik R, Sakthivel P, Singh CA, Jain D. SMARCB1 (INI1)-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: a series of 13 cases with assessment of histologic patterns. Hum Pathol. 2019;83:59–67.

Ayyanar P, Mishra P, Preetam C, Adhya AK. SMARCB1/INI1 deficient sino-nasal carcinoma: Extending the histomorphological features. Head Neck Pathol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-020-01246-9.

Kasajima A, Konukiewitz B, Schlitter AM, Weichert W, Bräsen JH, Agaimy A, Klöppel G. Mesenchymal/non-epithelial mimickers of neuroendocrine neoplasms with a focus on fusion gene-associated and SWI/SNF-deficient tumors. Virchows Arch. 2021;479:1209–19.

Dogan S, Cotzia P, Ptashkin RN, Nanjangud GJ, Xu B, Momeni Boroujeni A, Cohen MA, Pfister DG, Prasad ML, Antonescu CR, Chen Y, Gounder MM. Genetic basis of SMARCB1 protein loss in 22 sinonasal carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2020;104:105–16.

Agaimy A, Franchi A, Lund VJ, Skálová A, Bishop JA, Triantafyllou A, Andreasen S, Gnepp DR, Hellquist H, Thompson LDR, Rinaldo A, Ferlito A. Sinonasal Undifferentiated Carcinoma (SNUC): From an Entity to Morphologic Pattern and Back Again-A Historical Perspective. Adv Anat Pathol. 2020;27:51–60.

Pasricha S, Kamboj M, Jajodia A, Aggarwal M, Gupta G, Sharma A, Durga G, Mehta A. High grade myoepithelial carcinoma of maxillary sinus with extensive rhabdoid differentiation and INI-1 loss: Expanding the histopathological spectrum of sinonasal carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-021-01397-3.

Shah AA, Jain D, Ababneh E, Agaimy A, Hoschar AP, Griffith CC, Magliocca KR, Wenig BM, Rooper LM, Bishop JA. SMARCB1 (INI-1)-deficient adenocarcinoma of the sinonasal tract: A potentially under-recognized form of sinonasal adenocarcinoma with occasional yolk sac tumor-like features. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14:465–72.

Zamecnik M, Rychnovsky J, Syrovatka J. Sinonasal SMARCB1 (INI1) deficient carcinoma with yolk sac tumor differentiation: report of a case and comparison With INI1 expression in gonadal germ cell tumors. Int J Surg Pathol. 2018;26:245–9.

Li CY, Han YM, Xu K, Wu SY, Lin XY, Cao HY. Case report: SMARCB1 (INI-1)-deficient carcinoma of the nasal cavity with pure yolk sac tumor differentiation and elevated serum AFP levels. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;29:2227–33.

Hazir B, Şímșek B, Erdemír A, Gürler F, Yazici O, Kizil Y, Aydíl U. Sinonasal SMARCB1 (INI1) deficient carcinoma with yolk sac tumor differentiation: a case report and treatment options. Head Neck Pathol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-021-01375-9.

Witkowski L, Carrot-Zhang J, Albrecht S, Fahiminiya S, Hamel N, Tomiak E, Grynspan D, Saloustros E, Nadaf J, Rivera B, Gilpin C, Castellsagué E, Silva-Smith R, Plourde F, Wu M, Saskin A, Arseneault M, Karabakhtsian RG, Reilly EA, Ueland FR, Margiolaki A, Pavlakis K, Castellino SM, Lamovec J, Mackay HJ, Roth LM, Ulbright TM, Bender TA, Georgoulias V, Longy M, Berchuck A, Tischkowitz M, Nagel I, Siebert R, Stewart CJ, Arseneau J, McCluggage WG, Clarke BA, Riazalhosseini Y, Hasselblatt M, Majewski J, Foulkes WD. Germline and somatic SMARCA4 mutations characterize small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. Nat Genet. 2014;46:438–43.

Le Loarer F, Watson S, Pierron G, de Montpreville VT, Ballet S, Firmin N, Auguste A, Pissaloux D, Boyault S, Paindavoine S, Dechelotte PJ, Besse B, Vignaud JM, Brevet M, Fadel E, Richer W, Treilleux I, Masliah-Planchon J, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Zalcman G, Allory Y, Bourdeaut F, Thivolet-Bejui F, Ranchere-Vince D, Girard N, Lantuejoul S, Galateau-Sallé F, Coindre JM, Leary A, Delattre O, Blay JY, Tirode F. SMARCA4 inactivation defines a group of undifferentiated thoracic malignancies transcriptionally related to BAF-deficient sarcomas. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1200–5.

Strehl JD, Wachter DL, Fiedler J, Heimerl E, Beckmann MW, Hartmann A, Agaimy A. Pattern of SMARCB1 (INI1) and SMARCA4 (BRG1) in poorly differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus: analysis of a series with emphasis on a novel SMARCA4-deficient dedifferentiated rhabdoid variant. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015;19:198–202.

Agaimy A, Daum O, Märkl B, Lichtmannegger I, Michal M, Hartmann A. SWI/SNF complex-deficient undifferentiated/rhabdoid carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a series of 13 cases highlighting mutually exclusive loss of SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 and frequent co-inactivation of SMARCB1 and SMARCA2. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:544–53.

Conlon N, Silva A, Guerra E, Jelinic P, Schlappe BA, Olvera N, Mueller JJ, Tornos C, Jungbluth AA, Young RH, Oliva E, Levine D, Soslow RA. Loss of SMARCA4 expression is both sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of small cell carcinoma of ovary, hypercalcemic type. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:395–403.

Herpel E, Rieker RJ, Dienemann H, Muley T, Meister M, Hartmann A, Warth A, Agaimy A. SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 deficiency in non-small cell lung cancer: immunohistochemical survey of 316 consecutive specimens. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2017;26:47–51.

Perret R, Chalabreysse L, Watson S, Serre I, Garcia S, Forest F, Yvorel V, Pissaloux D, Thomas de Montpreville V, Masliah-Planchon J, Lantuejoul S, Brevet M, Blay JY, Coindre JM, Tirode F, Le Loarer F. SMARCA4-deficient thoracic sarcomas: clinicopathologic study of 30 cases with an emphasis on their nosology and differential diagnoses. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:455–65.

Agaimy A, Weichert W. SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:541–5.

Rekhtman N, Montecalvo J, Chang JC, Alex D, Ptashkin RN, Ai N, Sauter JL, Kezlarian B, Jungbluth A, Desmeules P, Beras A, Bishop JA, Plodkowski AJ, Gounder MM, Schoenfeld AJ, Namakydoust A, Li BT, Rudin CM, Riely GJ, Jones DR, Ladanyi M, Travis WD. SMARCA4-deficient thoracic sarcomatoid tumors represent primarily smoking-related undifferentiated carcinomas rather than primary thoracic sarcomas. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:231–47.

Jo VY, Chau NG, Hornick JL, Krane JF, Sholl LM. Recurrent IDH2 R172X mutations in sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:650–9.

Dogan S, Vasudevaraja V, Xu B, et al. DNA methylation-based classification of sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:1447–59.

Agaimy A, Jain D, Uddin N, Rooper LM, Bishop JA. SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: A series of 10 cases expanding the genetic spectrum of SWI/SNF-driven sinonasal malignancies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:703–10.

Kakkar A, Ashraf SF, Rathor A, Adhya AK, Mani S, Sikka K, Jain D. SMARCA4/BRG1-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: Morphologic spectrum of an evolving entity. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021 Dec 6.

Bishop JA, Westra WH. NUT midline carcinomas of the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1216–21.

Thompson ED, Stelow EB, Mills SE, Westra WH, Bishop JA. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the head and neck: a clinicopathologic series of 10 cases with an emphasis on HPV status. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:471–8.

Heffner DK, Hyams VJ. Teratocarcinosarcoma (malignant teratoma?) of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Cancer. 1984;53:2140–54.

Rooper LM, Bynum JP, Miller KP, Lin MT, Gagan J, Thompson LDR, Bishop JA. Recurrent DICER1 hotspot mutations in malignant thyroid gland teratomas: molecular characterization and proposal for a separate classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44(6):826–33.

Agaimy A, Witkowski L, Stoehr R, Cuenca JCC, González-Muller CA, Brütting A, Bährle M, Mantsopoulos K, Amin RMS, Hartmann A, Metzler M, Amr SS, Foulkes WD, Sobrinho-Simões M, Eloy C. Malignant teratoid tumor of the thyroid gland: an aggressive primitive multiphenotypic malignancy showing organotypical elements and frequent DICER1 alterations-is the term “thyroblastoma” more appropriate? Virchows Arch. 2020;477:787–98.

Rooper LM, Uddin N, Gagan J, Brosens LAA, Magliocca KR, Edgar MA, Thompson LDR, Agaimy A, Bishop JA. Recurrent loss of SMARCA4 in sinonasal teratocarcinosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:1331–9.

Fatima SS, Minhas K, Din NU, Fatima S, Ahmed A, Ahmad Z. Sinonasal teratocarcinosarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 6 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2013;17:313–8.

Chapurin N, Totten DJ, Morse JC, Khurram MS, Louis PC, Sinard RJ, Chowdhury NI. Treatment of sinonasal teratocarcinosarcoma: A systematic review and survival analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2021;35:132–41.

Agaimy A, Bishop JA. SWI/SNF-deficient head and neck neoplasms: An overview. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2021;38:175–82.

Birkeland AC, Burgin SJ, Yanik M, Scott MV, Bradford CR, McHugh JB, McLean SA, Sullivan SE, Nor JE, McKean EL, Brenner JC. Pathogenetic analysis of sinonasal teratocarcinosarcomas reveal actionable beta-catenin overexpression and a beta-catenin mutation. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2017;78:346–52.

Compton ML, Lewis JS Jr, Faquin WC, Cipriani NA, Shi Q, Ely KA. SALL-4 and beta-catenin expression in sinonasal teratocarcinosarcoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-021-01343-3.

Wang Y, Chen SY, Karnezis AN, Colborne S, Santos ND, Lang JD, Hendricks WP, Orlando KA, Yap D, Kommoss F, Bally MB, Morin GB, Trent JM, Weissman BE, Huntsman DG. The histone methyltransferase EZH2 is a therapeutic target in small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcaemic type. J Pathol. 2017;242:371–83.

Xue Y, Meehan B, Fu Z, Wang XQD, Fiset PO, Rieker R, Levins C, Kong T, Zhu X, Morin G, Skerritt L, Herpel E, Venneti S, Martinez D, Judkins AR, Jung S, Camilleri-Broet S, Gonzalez AV, Guiot MC, Lockwood WW, Spicer JD, Agaimy A, Pastor WA, Dostie J, Rak J, Foulkes WD, Huang S. SMARCA4 loss is synthetic lethal with CDK4/6 inhibition in non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2019;10:557.

Abou Alaiwi S, Nassar AH, Xie W, Bakouny Z, Berchuck JE, Braun DA, Baca SC, Nuzzo PV, Flippot R, Mouhieddine TH, Spurr LF, Li YY, Li T, Flaifel A, Steinharter JA, Margolis CA, Vokes NI, Du H, Shukla SA, Cherniack AD, Sonpavde G, Haddad RI, Awad MM, Giannakis M, Hodi FS, Liu XS, Signoretti S, Kadoch C, Freedman ML, Kwiatkowski DJ, Van Allen EM, Choueiri TK. Mammalian SWI/SNF complex genomic alterations and immune checkpoint blockade in solid tumors. Cancer Immunol Res. 2020;8:1075–84.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable (single author MS).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Agaimy, A. Proceedings of the North American Society of Head and Neck Pathology, Los Angeles, CA, March 20, 2022: SWI/SNF-deficient Sinonasal Neoplasms: An Overview. Head and Neck Pathol 16, 168–178 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-022-01416-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-022-01416-x