Abstract

As the COVID-19 pandemic hit the European continent at the beginning of 2020, one of the most significant socio-economic effects that immediately become the central focus of media and governing bodies was the unemployment and the sudden transformations suffered by the job market. This effect created major concerns for citizens and governing structures, as the pandemic generated a new and unparalleled economic context, where the short and medium-term future of several sectors seemed unpredictable. The concern acted upon the job insecurity of individuals, a perceived threat to the continuity and stability of their employment.

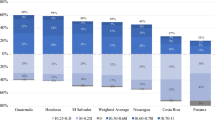

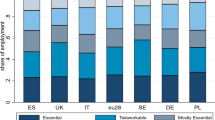

Based on a self-reported survey covering the first pandemic wave, our study classifies the regions (NUTS2 level) from six EU countries according to their performance in terms of job insecurity, but also the shock intensity (death rates and case fatality ratio), and identifies the overall over and under performers. The results show that the regional evolution of the job insecurity could be linked to the pandemic evolution, especially in the stronger economies. However, the model does not follow a classic economic core-periphery pattern. The model is challenged especially by a stronger performance of several less performant regions from Italy, Romania, or France.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant fall in economic growth worldwide. Faced with several waves of national lockdown and highly strict health measures, business changed their working models (Bailey et al. 2020; Lund et al. 2020). These changes often included employees being laid off or being sent into furlough for several months, being denied promotions or experiencing pay cuts (Basyouni and El Keshky 2021; Forbes and Krueger 2019; Nicola et al. 2020). With unemployment rates increasing, the levels of job insecurity among employees increased (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2020). Job insecurity during large-scale disruptions (e.g., natural disasters, economic recessions, epidemics) has been associated with high levels of anxiety and depression (Jeanne et al. 2020; Margerison-Zilko et al. 2016; Mihashi et al. 2009; Stanisławski 2019). Similarly, job insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic was linked to poor mental health among employees across the globe (Blanuša et al. 2021; Ganson et al. 2021; Obrenovic et al. 2021; San Too, Leach, and Butterworth 2021; Wilson et al. 2020).

Therefore, it is no surprise that during the past two decades, and especially after the crisis of 2008–2012, a constantly growing number of articles focused on job insecurity, trying to find the determinants, as well as emphasising the variations that the indicator tends to manifest during a shock. The variations were explained in a smaller or larger proportion through age (Yeves et al. 2019), gender (Menéndez-Espina et al. 2019), and level of education (Green 2009), the most common socio-demographical characteristics considered for complex analysis.

However, while socio-demographical determinants were thoroughly scrutinized by the scientific community during or following a socio-economic, geopolitical or pandemic shock, less effort was put in finding spatial implications of the job insecurity, despite numerous papers highlighting the importance of the regional economic situation (Amdaoud et al. 2020; Bourdin et al. 2021), especially in terms of job market evolution (Anderson and Pontusson 2007), the industrial contraction (Cooper and Antoniou 2013), or the overall resilience capacity of the governance systems (Harrison 2003), as job insecurity outmatches the job instability (Hassard and Morris 2018).

This study addresses this gap in the scientific literature by providing a longitudinal spatial interpretation and evolution of job insecurity during the first pandemic wave of COVID-19 in relation with the magnitude of the shock. The study is based on data gathered at personal level through one of the largest worldwide surveys applied during the pandemic (PsyCorona) correlated with data from regional and national institutions regarding the evolution of the case fatality ratio and death rates.

The paper is structured as follows: the following chapter is providing a thorough literature review on the topic of job insecurity and its connections with the socio-demographical and regional characteristics; the third chapter details the methodological approach, the sampling procedure, target population, and instrument validity; the fourth chapter presents the main results, while the last section offers an interpretation of the results, followed by several recommendations and the conclusions.

.

2 A literature review on job insecurity and its implications

Organisational psychologists defined job insecurity as a perceived helplessness to maintain continuity in a situation where individuals feel that their job might be threatened (Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt 1984). More specifically, individuals might experience a subjective fear of losing their job or specific features of their current job, e.g., promotions, remote working (Hellgren et al. 1999). According to De Witte (1999), job insecurity is a perceived subjective experience meaning that two individuals being in the same situation (e.g., part-time contracts) are likely to experience different levels or facets of job insecurity (van Vuuren 1999; Van Vuuren et al. 1991). Furthermore, job insecurity reflects an individual’s fears or assumptions concerning a job-related future event (e.g., having their working hours or salary cut, being laid off) that has not happened yet and in many circumstances will never happen (Mohr 2000; Probst 2003). It is worth mentioning that not all job-related events lead to individuals experiencing job insecurity. Boswell and colleagues (2014) underlined that only events that involve the constituents of potential harm or loss will lead to job insecurity. While threats are considered as perceptual, job insecurity feeds on uncertainty (Probst 2003; Sverke and Hellgren 2002; Sverke, Hellgren, and Näswall 2002). Hence, job insecurity explains the complexity of individuals’ perceptions and their responding relationship to elements of job loss in contradiction to the actual job or job loss elements (Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt 1984).

Job insecurity is defined as a stressful experience which is often associated with high levels of distress and negative feelings (Cheng and Chan 2008; Lim 1996). Given its potential to generate stress among those experiencing job insecurity, numerous studies evidenced its manifold negative consequences on mental, physical, and work-related wellbeing (Henseke 2018; Lee, Huang, and Ashford 2018; Llosa et al. 2018; Menéndez-Espina et al. 2019; De Witte, Pienaar, and De Cuyper 2016) such as depressive disorders (Blom et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2017), anxiety (Boya et al. 2008), heart diseases (Schnall, Dobson, and Landsbergis 2016), poor job attitudes, and decrease in performance, creativity, and adaptability (Niessen and Jimmieson 2016; Probst et al. 2007). Other studies showed that quantitative job insecurity is linked to low organizational commitment, and higher intentions to leave the organization (Shoss 2017) while qualitative job insecurity is associated to withdrawal attitudes and intentions (Hu and Zuo 2007).

Other studies looked at the link between job insecurity and sociodemographic characteristics such as age (Yeves et al. 2019), gender (Menéndez-Espina et al. 2019), and level of education (Green 2009). While some studies suggest that younger individuals experience higher levels of job insecurity (Keim et al. 2014; Roskies and Louis-Guerin 1990; Roskies, Louis‐Guerin, and Fournier 1993) most studies report that older individuals are subjected to higher levels of job insecurity (Claes and Van De Ven 2008; Mohr 2000; Näswall and De Witte 2003). These findings are explained by the fact that older individuals perceive themselves as less employable than young one (Peeters, De Cuyper, and De Witte 2016; Rothwell and Arnold 2007; Wittekind, Raeder, and Grote 2010) and thus are more dependent on their current jobs (Cheng and Chan 2008).

Regarding gender, some studies suggested that women feel less insecure compared to men because it is easier for them to find jobs (Charles and James 2003), while other studies argue that women report lower levels of job insecurity because they work in more protective organizations (Coron and Schmidt 2021). Furthermore, gender moderates the relationship between job insecurity and its consequences. Previous studies reported that job insecurity had more negative consequences on women’s attitudes towards work compared to men (Rosenblatt et al. 1999) and on men’s wellbeing compared to women (De Witte 1999). More recent studies showed no significant gender differences when it comes to job insecurity (Rigotti et al. 2015).

Regarding the level of education, previous studies underlined its role as a main predictor for job insecurity mainly because an individual’s chances of employment and/or reemployment are strongly linked to their level of education (Postel-Vinay and Turon 2007). A recent study by Klug (2020) showed that individuals with vocational qualifications experienced higher levels of job insecurity compared to university graduates. These results are in line with other findings suggesting that higher levels of education reduce job insecurity (Muñoz de Bustillo and de Pedraza 2010).

Despite the personal nature of the job insecurity, it must be acknowledged that recent studies, mostly developed following the economic crisis or at the beginning of the pandemic, managed to identify several spatial patterns regarding the variations in job insecurity during a shock. For example, during the financial crisis of 2008–2012, the self-reported values of job insecurity were higher in the Southern and Eastern peripheral countries of the European Union (Sverke et al. 2010; Symeonaki, Parsanoglou, and Stamatopoulou 2019), a model which was later explained by the economic prowess of the central and Northern part of the continent, as well as the more pertinent social measures (De Cuyper et al. 2018; Håkansson and Bejakovic 2020; László et al. 2010; Shoss 2017). Nevertheless, the abovementioned papers did not take into consideration the magnitude of the crisis in each part of the continent, as well as the regional implications of the shock when measuring the self-reported job insecurity.

3 Methodological approach

Our study is based on data collected through PsyCorona Study, an international psychological survey aimed at identifying the main potential psychological consequences of facing a pandemic situation and assessing key behaviours of citizensFootnote 1. The survey started in March 2020 and was the result of an international collaboration of over 100 researchers. Over 60.000 respondents answered the initial survey, available in 30 languages, during the first pandemic wave. After survey completion, the respondents could sign up to be contacted for follow-up surveys (psycorona.org). For the first two months, the surveys were sent weekly, then the frequency diminished to twice a week and then to once a month in order not to fatigue the respondents. Not all questions were sent out in each survey, as it was the case for job insecurity. For the current paper, we selected the waves where the measurement for job insecurity was available. The data collection processes were ensured in some countries by Qualtrics Panels.

The research was approved by the Ethics Committees of the University of Groningen (PSY-1920-S-0390) and New York University Abu Dhabi (HRPP-2020-42). In the current paper, we extracted only countries with representative samples (gender and age and for all waves) from the European Union (Germany, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Romania). The original questionnaire was created in English and translated for each country taking part in the survey in official language by the team of researchers.

The job insecurity was assessed on the Vander Elst scale (Vander Elst et al. 2014) and the respondents were asked to indicate the degree of self-perceived risk of losing their job (“Chances are, I will soon lose my job”) with a value varying from − 2 “Strongly disagree” (very low job insecurity) to 2 “Strongly agree” (very high job insecurity).

In order to correlate the job insecurity with the intensity of the shock during the first pandemic wave, we used data regarding the case fatality ratio and death rates at regional level from the ESPON Report “Geography of COVID-19: Territorial impacts of COVID-19 and policy answers in European regions and cities”Footnote 2. The ESPON report served as base for the delimitation of the period marking the first pandemic wave: from the end of February/beginning of March 2020 until mid-June 2020.

4 Results

The first element to take into consideration is the overall national evolution of the self-reported job insecurity during the first pandemic wave. The initial national values at the start of the survey (mid-March) varied from − 0.920 in Germany (lowest average of job insecurity from the sample) to − 0.488 in Italy (highest average). However, as the pandemic extended, the overall self-reported values constantly decreased, a sign of the adaptation of the citizens to the new context. At the end of the first pandemic wave, the job insecurity across the countries selected for our study showed an overall improvement, with values varying from − 1.451 in Germany to − 0.717 in Romania (Table 1).

However, the overall national values of job insecurity do not reflect the more detailed territorial impact. For this kind of picture, we need to advance to a more granular level, therefore, based on the regional location provided by the respondents (NUTS2 administrative units, except for Germany, where the location was provided at NUTS1 level) we managed to identify the overperforming and underperforming regions in terms of job insecurity. Since the evolution was strongly dependent on the national context, the classification of over or under performing was made by reporting the regional score to the national average. Moreover, using the same methodological approach, we identified the over and underperforming regions regarding the shock intensity (case fatality ratio and death rates) and correlated the results by creating four classes of regions.

The resulting maps (Figs. 1 and 2) show two different types of region. On one hand, the overall overperformers (Class 1) and the overall underperformers (Class 4), where the evolution of job insecurity can be connected with the evolution of the intensity of the shock: these regions tend to cover the majority of France, the Netherlands, and Italy. On the other hand, the regions where the evolution of job insecurity was not connected with the intensity of the shock (Class 2 and Class 3): these regions, mostly from Spain and Romania managed to perform either in job insecurity, either in shock intensity, but not in both.

The regional repartition in classes according to the evolution of job insecurity and the case fatality ratio* during the first pandemic wave

(1 – overperformers in both job insecurity and case fatality ratio; 2 – overperformers in terms of job insecurity, underperformers in terms of case fatality ratio; 3 – underperformers in terms of job insecurity, overperformers in terms of case fatality ratio; 4 – underperformers in both job insecurity and case fatality ratio; 5 – insufficient data)

* Case fatality ratio (CFR) or more precisely case-fatality risk (CFR) is the percentage (%) of persons diagnosed with a disease (COVID-19 in this case) and who die from it. CFRs are usually used to assess diseases with discrete and limited time courses. Source: ESPON Report, Geography of COVID-19.

The regional repartition in classes according to the evolution of job insecurity and death rates* during the first pandemic wave

(1 – overperformers in both job insecurity and death rates; 2 – overperformers in terms of job insecurity, underperformers in terms of death rates; 3 – underperformers in terms of job insecurity, overperformers in terms of death rates; 4 – underperformers in both job insecurity and death rates; 5 – insufficient data)

* Death rate represents the COVID-19 death rates per 10,000 inhabitants. Source: ESPON Report, Geography of COVID-19.

Interesting overlapping between the two maps indicate that regions from North of Italy, West of France, West of Romania showed similar classes when the job insecurity was put in relation with both case fatality ratio and death rates. On the other hand, for the most part of Germany, Spain, or South of Romania, the regions overperformed or underperformed differently according to each indicator of shock intensity. This could be due to difference in population structure, health infrastructure performance, health systems and particular answers of regional and local actors to the pandemic.

5 Discussions and conclusions

Our results are similar to findings from literature that signalled the existence of a certain North-South gradient in terms of job insecurity (De Cuyper et al. 2018; Näswall and De Witte 2003; Shoss 2017; Sverke et al. 2010; Symeonaki, Parsanoglou, and Stamatopoulou 2019), as the southern regions of Spain, France, or Italy tend to underperform in terms of job insecurity, even when they overperform in terms of case fatality ratio. However, the most surprising result was that in the most developed economies the evolution of the job insecurity during the first pandemic wave followed the evolution of the intensity of the shock, either in terms of case fatality ratio, either in terms of death rates. The behaviour, prevalent in France, Germany, and the Netherlands is more visible when the job insecurity is correlated with case fatality ratio, and less visible when correlated with death rates. This may be due to the fact that case fatality ratio represents a more precise indicator of the shock’s impact, giving that its value is taking into consideration the number of persons diagnosticated with COVID-19. Therefore, from an individual (and even statistical) perspective, this indicator manages to better display the “gravity” of the situation.

Another finding which deserve attention is the overperforming behaviour in terms of job insecurity of less economic performant regions from Italy (south), Romania (centre and north-east), or France (central part). This challenges the classic stereotype in terms of core-periphery relation existent in literature.

Giving that job insecurity tend to react to shock intensity, governing bodies need to pay attention to the future evolution of job insecurity and its social effects. And while the pandemic effects are less visible than during the first semester of 2020, the new geopolitical and economic challenges foreseen for the beginning of 2023 have a tremendous effect on the self-perceived job insecurity of individuals (Rydzik and Bal, 2023). Amid incertitude, many millions of Europeans will worry about job loss or job quality decline. And while job insecurity may reduce one’s life satisfaction, ground based policy interventions can make a difference (Carr and Chung 2014; László et al. 2010). Therefore, instead of waiting the triggering of a new shock that could generate a huge spike in job insecurity, the development of an EU-wide support mechanism can provide short and medium term social benefits.

Further data collection on health systems and health infrastructure at regional level is required in order to better understand how the relation between job insecurity and shock intensity acts for sub-national structures.

References

Amdaoud, M., et al.: “Geography of COVID-19 Outbreak and First Policy Answers in European Regions and Cities.” (2020)

Anderson, C.J., and Jonas Pontusson: Workers, worries and Welfare States: Social Protection and Job Insecurity in 15 OECD Countries. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 46(2), 211–235 (2007)

Bailey, D., et al.: Regions in a time of pandemic. Reg. Stud. 54(9), 1163–1174 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1798611

Basyouni, S.S., and Mogeda El Sayed El Keshky: Job insecurity, work-related Flow, and financial anxiety in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic and economic downturn. Front. Psychol. 12, 632265 (2021)

Blanuša, J., Barzut, V., Knežević, J.: “Intolerance of Uncertainty and Fear of COVID-19 Moderating Role in Relationship between Job Insecurity and Work-Related Distress in the Republic of Serbia.”Frontiers in Psychology:2170. (2021)

Blom, V., Richter, A., Hallsten, L., and Pia Svedberg: The Associations between Job Insecurity, depressive symptoms and burnout: The role of performance-based self-esteem. Econ. Ind. Democr. 39(1), 48–63 (2018)

Boswell, W.R., Julie, B., Olson-Buchanan, Brad Harris, T.: I cannot afford to have a life: Employee adaptation to feelings of Job Insecurity. Pers. Psychol. 67(4), 887–915 (2014)

Bourdin, S., Jeanne, L., Nadou, F., and Gabriel Noiret: Does Lockdown work? A spatial analysis of the spread and concentration of COVID-19 in Italy. Reg. Stud. 1–12 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1887471

Boya, F., Özyaman, et al.: Effects of Perceived Job Insecurity on Perceived anxiety and depression in nurses. Ind. Health. 46(6), 613–619 (2008)

Carr, E., and Heejung Chung: Employment insecurity and life satisfaction: The moderating influence of Labour Market Policies across Europe. J. Eur. Social Policy. 24(4), 383–399 (2014)

Charles, N., and Emma James: The gender dimensions of Job Insecurity in a local Labour Market. Work Employ. Soc. 17(3), 531–552 (2003)

Cheng, G.H.L., Darius K‐S, C.: Who suffers more from Job Insecurity? A Meta‐analytic review. Appl. Psychol. 57(2), 272–303 (2008)

Claes, R., and Bart Van De Ven: Determinants of older and younger workers’ job satisfaction and Organisational Commitment in the contrasting Labour Markets of Belgium and Sweden. Aging Soc. 28(8), 1093 (2008)

Cooper, C.L., Antoniou, A.S.G.: The Psychology of the Recession on the Workplace. Edward Elgar (2013). https://books.google.ro/books?id=UG0OmYmSKQsC

Coron, C.: and Géraldine Schmidt. “The ‘Gender Face’of Job Insecurity in France: An Individual-and Organizational-Level Analysis.”Work, Employment and Society:0950017021995673. (2021)

De Cuyper, Nele, B., Piccoli, R., Fontinha, Hans De, Witte: Job insecurity, employability and satisfaction among Temporary and Permanent Employees in Post-Crisis Europe. Econ. Ind. Democr. 40(2), 173–192 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X18804655

Vander Elst, T., De Witte, H., De Cuyper, N.: The Job Insecurity Scale: A psychometric evaluation across five European countries. Eur. J. Work Organizational Psychol. 23(3), 364–380 (2014)

Forbes, M.K., Robert, F.K.: The great recession and Mental Health in the United States. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 7(5), 900–913 (2019)

Ganson, K.T., et al.: Job insecurity and symptoms of anxiety and depression among US Young adults during COVID-19. J. Adolesc. Health. 68(1), 53–56 (2021)

Green, F.: Subjective employment insecurity around the World. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2(3), 343–363 (2009)

Greenhalgh, L., and Zehava Rosenblatt: Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. Acad. Manage. Rev. 9(3), 438–448 (1984)

Håkansson, P., and Predrag Bejakovic: Labour Market Resilience, Bottlenecks and spatial mobility in Croatia. East. J. Eur. Stud. 11(2), 5–25 (2020)

Harrison, N.: “Good Governance: Complexity, Institutions, and Resilience.” In Open Meeting of the Global Environmental Change Research Community, Montreal, 1–22. (2003)

Hassard, J., and Jonathan Morris: Contrived competition and manufactured uncertainty: Understanding managerial job insecurity narratives in large corporations. Work Employ. Soc. 32(3), 564–580 (2018)

Hellgren, J., Sverke, M., Isaksson, K.: A Two-Dimensional Approach to Job Insecurity: Consequences for employee attitudes and well-being. Eur. J. work organizational Psychol. 8(2), 179–195 (1999)

Henseke, G.: Good Jobs, Good Pay, Better Health? The Effects of Job Quality on Health among older european workers. Eur. J. Health Econ. 19(1), 59–73 (2018)

Hu, S., and Bin Zuo: The moderating effect of Leader-Member Exchange on the job insecurity-organizational commitment relationship. In: Wang, W., et al. (eds.) Integration and Innovation Orient to E-Society Volume 2, pp. 505–513. Springer, Boston, MA (2007)

Jeanne, L., Bourdin, S., Nadou, F.: and Gabriel Noiret. “Economic Globalization and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Global Spread and Inequalities.” Bull. World Health Organ April 2020. (2020)

Keim, A.C., Ronald, S., Landis, C.A., Pierce, and David R Earnest: Why do employees worry about their Jobs? A Meta-Analytic Review of Predictors of Job Insecurity. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 19(3), 269 (2014)

Kim, M.-S., Hong, Y.-C., Yook, J.-H., Mo-Yeol, K.: Effects of Perceived Job Insecurity on Depression, suicide ideation, and decline in Self-Rated Health in Korea: A Population-Based panel study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 90(7), 663–671 (2017)

Klug, K.: Young and at risk? Consequences of Job Insecurity for Mental Health and satisfaction among Labor Market Entrants with different levels of education. Econ. Ind. Democr. 41(3), 562–585 (2020)

László, K.D., et al.: Job insecurity and health: A study of 16 european countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 70(6), 867–874 (2010). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S027795360900817X

Lee, C., Huang, G.-H., Susan, J.A.: Job insecurity and the changing workplace: Recent developments and the future Trends in Job Insecurity Research. Annual Rev. Organizational Psychol. Organizational Behav. 5, 335–359 (2018)

Lim, Vivien, K.G.: Job insecurity and its outcomes: Moderating Effects of Work-Based and Nonwork-Based Social Support. Hum. Relat. 49(2), 171–194 (1996)

Llosa, J.A.: Sara Menéndez-Espina, Esteban Agulló-Tomás, and Julio Rodríguez-Suárez. “Job Insecurity and Mental Health: A Meta-Analytical Review of the Consequences of Precarious Work in Clinical Disorders.” Anales de psicología. (2018)

Lund, S., Ellingrud, K., Hancock, B., Manyika, J.: 29 McKinsey Global Institute, April COVID-19 and Jobs: Monitoring the US Impact on People and Places. (2020)

Margerison-Zilko, C., Goldman-Mellor, S., Falconi, A., and Janelle Downing: Health Impacts of the great recession: A critical review. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 3(1), 81–91 (2016)

Menéndez-Espina, S., et al.: Job insecurity and Mental Health: The moderating role of coping strategies from a gender perspective. Front. Psychol. 10, 286 (2019)

Mihashi, M., et al.: Predictive factors of psychological Disorder Development during Recovery following SARS Outbreak. Health Psychol. 28(1), 91–110 (2009)

Mohr, G.B.: The changing significance of different stressors after the announcement of Bankruptcy: A longitudinal investigation with special emphasis on Job Insecurity. J. organizational Behav. 21(3), 337–359 (2000)

de Muñoz, R., and Pablo de Pedraza: Determinants of Job Insecurity in five european countries. Eur. J. Ind. Relat. 16(1), 5–20 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680109355306

Näswall, K., and Hans De Witte: Who feels Insecure in Europe? Predicting Job insecurity from background variables. Econ. Ind. Democr. 24(2), 189–215 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X03024002003

Nicola, M., et al.: The Socio-Economic Implications of the Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 78, 185–193 (2020). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1743919120303162

Niessen, C., Nerina, L.J.: Threat of Resource loss: The role of Self-Regulation in Adaptive Task Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 101(3), 450 (2016)

Obrenovic, B., et al.: The threat of COVID-19 and Job Insecurity Impact on Depression and anxiety: An empirical study in the USA. Front. Psychol. 12, 648572 (2021)

Peeters, E.R., Nele, De Cuyper, and Hans De Witte: Too employable to feel well? Curvilinear relationship between Perceived Employability and Employee Optimal Functioning. Psihologia Resurselor Umane. 14(1), 35–44 (2016)

Postel-Vinay, F., and Hélène Turon: The Public Pay Gap in Britain: Small differences that (don’t?) Matter. Econ. J. 117(523), 1460–1503 (2007)

Probst, T.M.: Development and validation of the Job Security Index and the Job Security satisfaction scale: A classical test theory and IRT Approach. J. Occup. Organizational Psychol. 76(4), 451–467 (2003)

Probst, T.M., Susan, M., Stewart, M.L., Gruys, Bradley, W.T.: Productivity, Counterproductivity and Creativity: The Ups and Downs of Job Insecurity. J. Occup. Organizational Psychol. 80(3), 479–497 (2007)

Rigotti, T., Mohr, G., Isaksson, K.: Job Insecurity among Temporary Workers: Looking through the gender Lens. Econ. Ind. Democr. 36(3), 523–547 (2015)

Rydzik, A., Bal, P., Matthijs: The age of insecuritisation: Insecure young workers in insecure jobs facing an insecure future. Hum. Resource Manage. J. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12490

Rosenblatt, Z., Talmud, I., Ruvio, A.: A gender-based Framework of the experience of Job Insecurity and its Effects on Work Attitudes. Eur. J. work organizational Psychol. 8(2), 197–217 (1999)

Roskies, E., and Christiane Louis-Guerin: Job insecurity in managers: Antecedents and consequences. J. organizational Behav. 11(5), 345–359 (1990)

Roskies, E., Christiane Louis-Guerin, and Claudette Fournier: Coping with Job Insecurity: How does personality make a difference? J. organizational Behav. 14(7), 617–630 (1993)

Rothwell, A., and John Arnold: Self-perceived employability: Development and validation of a scale. Personnel Rev. 36(1), 23–41 (2007)

San Too, Lay, L., Leach, Butterworth, P.: Cumulative impact of high job demands, low Job Control and high job insecurity on midlife depression and anxiety: A prospective cohort study of australian employees. Occup. Environ. Med. 78(6), 400–408 (2021)

Schnall, P.L., Marnie, Dobson, and Paul Landsbergis: Globalization, work, and Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Health Serv. 46(4), 656–692 (2016)

Shoss, M.K.: Job insecurity: An integrative review and agenda for Future Research. J. Manag. 43(6), 1911–1939 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317691574

Stanisławski, K.: The coping Circumplex Model: An integrative model of the structure of coping with stress. Front. Psychol. 10, 694 (2019)

Sverke, M., and Johnny Hellgren: The Nature of Job Insecurity: Understanding employment uncertainty on the Brink of a New Millennium. Appl. Psychol. 51(1), 23–42 (2002)

Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., Näswall, K.: No security: A Meta-analysis and review of Job Insecurity and its consequences. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 7(3), 242–264 (2002)

Sverke, M., Witte, H.D., Näswall, K., and Johnny Hellgren: European perspectives on Job Insecurity: Editorial introduction. Econ. Ind. Democr. 31(2), 175–178 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X10365601

Symeonaki, M., Parsanoglou, D., and Glykeria Stamatopoulou: The evolution of early job insecurity in Europe. SAGE Open. 9(2), 2158244019845187 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019845187

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics:. Employment Situation Summary. (2020). https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm

van Vuuren, B.K.: Job insecurity: Introduction. Eur. J. Work Organizational Psychol. 8(2), 145–153 (1999)

Van Vuuren, T., Klandermans, B., Jacobson, D., Hartley, J.: Employees’ reactions to Job Insecurity. In: Hartley, J., Jacobson, D., Klandermans, B. (eds.) Job Insecurity: Coping with Jobs at Risk, pp. 79–103. Van Vuuren, London (1991)

Wilson, J.M., et al.: Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 Pandemic are Associated with worse Mental Health. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 62(9), 686–691 (2020)

De Witte, H.: Job Insecurity and Psychological Well-Being: Review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. Eur. J. work Organizational Psychol. 8(2), 155–177 (1999)

De Witte, Hans, J., Pienaar, and Nele De Cuyper: Review of 30 years of Longitudinal Studies on the Association between Job Insecurity and Health and Well-being: Is there causal evidence? Australian Psychol. 51(1), 18–31 (2016)

Wittekind, A., Raeder, S., Grote, G.: A longitudinal study of determinants of Perceived Employability. J. Organizational Behav. 31(4), 566–586 (2010)

Yeves, J., et al.: Age and perceived employability as moderators of job insecurity and job satisfaction: A Moderated Moderation Model. Front. Psychol. 10, 799 (2019)

Funding

This research has been conducted with the support of the Erasmus + programme of the European Union, within the Project no. 621,262-EPP-1-2020-1-RO-EPPJMO-MODULE ‘Jean Monnet Module on EU Interdisciplinary Studies: Widening Knowledge for a more Resilient Union (EURES)’, co-financed by European Commission in the framework of Jean Monnet Action and the ESPON TERRCOV Project (Geography of COVID-19 Territorial impacts of COVID-19 and policy answers in European regions and cities).

The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Bogdan-Constantin Ibanescu, Mioara Cristea, and Alexandra Gheorghiu. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Gabriela Carmen Pascariu and Bogdan-Constantin Ibanescu and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Compliance with ethical standards

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibanescu, BC., Cristea, M., Gheorghiu, A. et al. The regional evolution of job insecurity during the first COVID-19 wave in relation to the pandemic intensity. Lett Spat Resour Sci 16, 13 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-023-00337-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-023-00337-9