Abstract

Purpose

Entecavir demonstrated superior virologic and biochemical benefits over lamivudine at 48 weeks in nucleoside-naïve Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB). We evaluated the effect of continued entecavir and lamivudine treatment in patients who continued treatment in year 2 and the off-treatment durability of patients who achieved a protocol-defined consolidated response at week 48.

Methods

Chinese adults (n = 519) with CHB were randomized to a minimum of 52 weeks of treatment with entecavir 0.5 mg/day or lamivudine 100 mg/day. Patients with a consolidated response at week 48 (HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml for ≥24 weeks, ALT <1.25 times ULN, and, if HBeAg(+) at baseline, loss of HBeAg for at least 24 weeks) stopped treatment at week 52 and were followed off-treatment. Patients with a partial response at week 48 (HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml in the absence of other criteria for a consolidated response) could continue blinded treatment for up to 96 weeks. Patients were assessed for HBV DNA, ALT normalization, safety, and, if HBeAg(+) at baseline, for HBe seroconversion. Cumulative proportions of all treated patients who ever achieved these responses were also analyzed.

Results

Among patients treated during year 2 (entecavir: n = 193; lamivudine: n = 145), 74% of entecavir-treated and 41% of lamivudine-treated patients had HBV DNA <300 copies/ml by PCR at end of dosing and 96% of entecavir-treated and 82% of lamivudine-treated patients normalized ALT. Eleven percent of entecavir-treated versus 19% of lamivudine-treated patients underwent HBe seroconversion during year 2. Cumulative confirmed analysis for all treated patients through 96 weeks showed that 79% of entecavir-treated versus 46% of lamivudine-treated patients (p < 0.0001) achieved HBV DNA <300 copies/ml by PCR. Similar proportions of entecavir- and lamivudine-treated patients achieved confirmed ALT normalization and HBe seroconversion. Safety profile was comparable for both treatment groups.

Conclusions

Through 96 weeks of treatment, entecavir resulted in continued clinical benefit in nucleoside-naïve Chinese patients with CHB, with a safety profile comparable with lamivudine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately 400 million people are chronically infected with HBV, and the worldwide burden of hepatitis B is greatest in China, where vertical transmission of HBV predominates [1]. HBV contributes directly to the increased risk of liver disease in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) [2–4]. A linear dose–response relationship exists between the concentration of HBV DNA in serum and the risk of developing cirrhosis and HCC in this population [2, 3]. Suppressing replication of HBV with nucleoside analogues reduces morbidity and mortality in patients with CHB and advanced hepatic fibrosis [5]. The goal of therapy for CHB, therefore, is a rapid and sustained reduction of the serum HBV DNA to the lowest possible level [6]. Durable suppression of HBV DNA replication, in turn, results in histologic improvement, normalization of ALT, and in some patients with HBeAg(+) infection, seroconversion to an anti-HBe state.

The emergence of resistant viral strains is an important consideration when selecting a nucleoside analogue. The very large pool of HBV in circulation, the rapid turnover rate, and the high error rate in HBV replication mean that any potential mutant, including those that give rise to drug resistance, may be present in a patient before he or she starts therapy [7]. The emergence of lamivudine resistance before and during therapy limits the usefulness of this drug. The prevalence of lamivudine genotypic resistance is reported to be 24, 42, and 70% after 1, 2, and 4 years of continuous treatment, respectively [8]. An adefovir phase III trial in HBeAg(−) patients reports cumulative probabilities of genotypic resistance to adefovir at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years of 0, 3, 11, 19, and 30%, respectively [9]. Telbivudine selects for mutations in the YMDD motif and, although it is associated with lower resistance than lamivudine, recently reported virologic breakthrough due to resistance substitutions was 21.6% and 8.6% in HBeAg(+) and HBeAg(−) patients after 2 years of treatment [10]. The lowest reported rates of resistance after 5 years of treatment have been obtained with entecavir (<1%) [7, 11, 12].

Entecavir, a potent guanosine analogue, significantly increased survival in an animal model of chronic HBV infection [13]. Entecavir (0.5 mg/day for nucleoside-naïve patients or 1 mg/day for lamivudine-refractory patients) produced significant virologic, histologic, and biochemical improvement in a series of large randomized multicenter phase III trials that encompassed a broad spectrum of clinical situations, including nucleoside-naïve patients with HBeAg(+) [14] and HBeAg(−) infection [15], and treatment-experienced patients with lamivudine-refractory HBV [16]. In nucleoside-naive patients, entecavir was superior to lamivudine (100 mg/day) for histologic, virologic, and biochemical outcomes, and entecavir resistance after 1 year of treatment was rare (<1%) [11, 14]. Long-term follow-up demonstrates that suppression of HBV DNA replication is maintained throughout 2 and even 3–4 years of treatment with entecavir and that the rate of resistance is less than 1% after 4 years [12, 17, 18].

The efficacy and safety of entecavir have also been studied in nucleoside-naïve Chinese patients with CHB, 76% of whom had HBV DNA < 300 copies/ml by PCR assay after 48 weeks of treatment (vs. 43% with lamivudine, p < 0.0001) [19]. The present analysis evaluates the efficacy and safety of entecavir and lamivudine in patients who failed to achieve a protocol-defined consolidated response at week 48 and continued treatment in year 2, as well as the off-treatment durability of patients who achieved a protocol-defined consolidated response at week 48.

Methods

The complete study design and patient selection criteria for the trial have been published elsewhere [19].

Patients

Chinese patients eligible for the trial had CHB, were aged 16 years or older, and had a serum HBV DNA level ≥3 MEq/ml by Quantiplex™ branched-chain DNA assay and an ALT level between 1.3 and 10 times the ULN. Both HBeAg(+) and HBeAg(−) patients could be enrolled. Participants were required to have compensated liver disease defined as a total serum bilirubin level ≤2.5 mg/dl, prothrombin time ≤3 s longer than the normal control value (or an international normalized ratio ≤1.5), serum albumin ≥3.0 g/dl, and no current evidence or history of variceal bleeding or hepatic encephalopathy (i.e., Child-Pugh class A).

Patients were excluded if they had received previous treatment with a nucleoside or nucleotide analogue with anti-HBV activity for 12 weeks or more at any time or had received any anti-HBV therapy, including interferon or thymosin alpha-1, within 24 weeks before randomization. Patients with evidence of infection by hepatitis C or D viruses or human immunodeficiency virus were excluded. Individuals with current evidence or a history of liver or pancreatic tumors were excluded; ultrasound was done before randomization to confirm the absence of focal lesions suggestive of cancer.

Study design

Patients eligible for this multicenter study were randomized to at least 52 weeks of double-blind, double-dummy treatment with either entecavir (Baraclude®, Bristol-Myers Squibb) 0.5 mg once daily or lamivudine (Epivir-HBV, GlaxoSmithKline) 100 mg once daily. The protocol-defined management of patients after week 52 was based on the HBV DNA level as determined by Quantiplex™ bDNA assay (approved assay at the time of protocol development), HBeAg status, and serum ALT level at week 48. This design evaluated whether therapy could be discontinued once certain treatment end points were achieved.

Patients with a consolidated response at week 48 had HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml by Quantiplex™ bDNA assay for at least 24 weeks, a serum ALT level <1.25 times ULN, and, if they were HBeAg(+) at baseline, were HBeAg(−) for at least 24 weeks (i.e., at weeks 24, 36, and 48). Individuals with a consolidated response stopped study drug treatment at week 52 and were monitored for a further 24 weeks to determine whether they had a sustained response.

Patients with a partial response had HBV DNA <0.7 MEq/ml at week 48, but did not meet all of the criteria for a consolidated response. Individuals with a partial response could continue double-blind treatment until they achieved a consolidated response or until they had completed 96 weeks of treatment, whichever came first. Patients with a partial response at week 48 who achieved a consolidated response during weeks 52–96 of treatment discontinued study drug treatment for up to 24 weeks follow-up. Patients who experienced a virologic breakthrough, defined as two consecutive HBV DNA measurements ≥1 log10 above nadir during weeks 52–96 of treatment and up to 24 weeks off-treatment follow-up, could elect to enroll in a separate entecavir protocol.

Patients with a nonresponse had HBV DNA ≥0.7 MEq/ml at week 48. These individuals discontinued study drug treatment at week 52 and were offered enrollment in an entecavir rollover protocol or off-study alternative anti-HBV therapy as recommended by the investigator. Patients discontinuing entecavir were monitored for a further 24 weeks for safety.

Efficacy assessment

For virologic responders who continued treatment beyond week 48, efficacy end points through 96 weeks of treatment included the proportion of patients with HBV DNA <300 copies/ml as measured by a sensitive PCR assay (Roche COBAS Amplicor assay, limit of detection 300 copies/ml [57 IU/ml]). Other efficacy end points were the proportion of patients with normalization of serum ALT (i.e., ≤1.0 times ULN) and HBeAg loss and HBe seroconversion (in patients who were HBeAg(+) at baseline) at EOD (i.e., at the last on-treatment observation).

A cumulative efficacy analysis using data for all treated patients (entecavir: n = 258; lamivudine: n = 261) was also conducted to evaluate the cumulative probability of ever achieving a confirmed end point for up to 2 years of treatment. The cumulative confirmed response is defined as the cumulative proportion of treated patients who achieved a given endpoint (HBV DNA <300 copies/ml, ALT ≤1.0 times ULN, HBeAg loss or HBe seroconversion) at some point up to and including week 96. A confirmed end point was one that was documented on two sequential measurements or at the last on-treatment measurement.

Patients with a consolidated response during year 1 or 2 of treatment were evaluated for HBV DNA, ALT normalization, and HBe seroconversion and monitored for 24 weeks off-treatment to determine whether they sustained these responses.

Safety assessment

Safety was assessed by laboratory testing and evaluation of adverse events during treatment and follow-up. Important safety end points included the proportion of patients discontinuing treatment because of adverse events, the proportions of patients with adverse events, serious adverse events, laboratory abnormalities (i.e., ALT flares defined as >2 times the baseline value and ≥10 times ULN), and deaths.

Statistical analysis

The details of the sample size calculation have been described elsewhere [19]. Confidence intervals and p values for differences in proportions are based on the normal approximation to the binomial distribution, with unpooled proportions used in the computation of the standard error of the difference. The p values are based on 2-sided tests. For the analysis of efficacy end points for the year 2 treatment cohort, the proportion of subjects who achieved an end point at EOD is presented for each treatment group. No statistical comparisons can be made of such treatment groups. For consolidated responders at week 48 or EOD, sustained response during the 24-week off-treatment follow-up phase is also described. Safety analyses tabulate the proportion of subjects with events on-treatment and during off-treatment follow-up.

Results

Of 519 patients randomized and treated in year 1 (entecavir: n = 258; lamivudine: n = 261), 50 (19.4%) entecavir recipients and 40 (15.3%) lamivudine recipients achieved a consolidated response at week 48, discontinued treatment at week 52, and were further followed off-treatment for up to 24 weeks. Eight (3.1%) entecavir recipients and 62 (23.8%) lamivudine-treated patients were nonresponders at week 48 and discontinued therapy at week 52. A total of 193 (74.8%) entecavir recipients and 146 (55.9%) lamivudine recipients achieved a virologic response at week 48 and all but one lamivudine-treated patient continued therapy in year 2 of the trial. The flow of patients through the trial is depicted in Fig. 1. Baseline characteristics of patients have been presented elsewhere [19].

During year 2 of the study, fewer entecavir-treated than lamivudine-treated patients discontinued treatment (16 vs. 50). Reasons for discontinuing treatment included virologic breakthrough (entecavir: n = 6; lamivudine: n = 46), lost to follow-up (entecavir: n = 4; lamivudine: n = 1), withdrawal of consent (entecavir: n = 2; lamivudine: n = 2), pregnancy (entecavir: n = 1; lamivudine: n = 1), noncompliance (entecavir: n = 1), and other reasons (entecavir: n = 2). The median time on therapy for patients treated with entecavir was 95.7 weeks, with 177 patients completing year 2. The median time on therapy for patients treated with lamivudine was 66.7 weeks, with 95 patients completing year 2.

Virologic, biochemical, and serologic responses

Virologic response

Among subjects treated in year 2 (entecavir: n = 193; lamivudine: n = 145), the mean change from baseline in HBV DNA by PCR assay (log10 copies/ml) remained stable between week 48 and EOD in the entecavir group (−6.09 and −6.04, respectively) and decreased in the lamivudine group (−5.16 at week 48, −3.92 at EOD). The proportion of patients with HBV DNA <300 copies/ml by PCR was maintained throughout year 2 of treatment with entecavir. A total of 76% and 74% of entecavir-treated patients had HBV DNA <300 copies/ml at week 48 and at EOD, respectively (Table 1). In comparison, fewer lamivudine-treated patients had HBV DNA <300 copies/ml after 1 year of treatment (52%) and the proportion declined to 41% at EOD (Table 1).

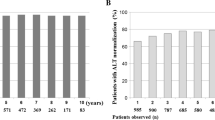

Among all treated patients, the cumulative proportion of patients with HBV DNA <300 copies/ml was significantly greater (p < 0.0001) among patients treated with entecavir (204/258; 79%) than among those treated with lamivudine (121/261, 46%) (Table 2).

Biochemical response

Most patients in the year 2 cohort had ALT ≤ 1.0 times ULN at week 48. While proportions of patients with normalized ALT increased at EOD among entecavir-treated patients (91% at week 48, 96% at EOD), they declined among patients treated with lamivudine (88% at week 48 and 82% at EOD) (Table 1).

Among all treated patients, the cumulative proportion with confirmed ALT normalization (≤1.0 times ULN) through 96 weeks was greater among patients treated with entecavir (248/258; 96%) than lamivudine (241/261, 92%) (p = 0.06) (Table 2).

Serologic response

Among HBeAg(+) patients included in the year 2 cohort, 8% of entecavir recipients (15/186) and 17% of lamivudine-treated patients (23/135) had lost HBeAg after 1 year of dosing. At EOD in these individuals, 18% of entecavir recipients (34/186) and 25% of lamivudine-treated patients (34/135) had lost HBeAg, and 11% of entecavir recipients (20/186) and 19% of lamivudine-treated patients (25/135) had undergone HBe seroconversion (Table 1).

Among patients who were HBeAg(+) at baseline, the cumulative proportion with confirmed loss of HBeAg through 96 weeks was 27% for both treatment groups (entecavir: n = 61/225; lamivudine: n = 59/221) (Table 2). The cumulative proportion with confirmed HBe seroconversion was 21% in those treated with entecavir (48/225) and 23% in those treated with lamivudine (51/221) (Table 2). No patients lost HBsAg during the trial.

Protocol-defined outcomes through year 2

During year 2 of therapy, an additional 27 of 193 (14%) entecavir-treated and 23 of 145 (16%) lamivudine-treated patients achieved the protocol-defined response of HBV DNA level <0.7 mEq/ml, ALT <1.25 times ULN, and loss of HBeAg (if HBeAg[+]).

Over the full 96-week duration of the study, 77 of 258 (29.8%) patients on entecavir (50 at week 48, plus 27 during year 2) had a consolidated response, as compared with 63 of 261 (24.1%) patients on lamivudine (40 at week 48, plus 23 during year 2). Fewer entecavir-treated (11, 4%) than lamivudine-treated patients (108, 41%) were deemed to be nonresponders throughout the 96 weeks of treatment.

Patients with sustained response

At week 48 or EOD, 76 (99%) entecavir-treated patients with a consolidated response had HBV DNA <300 copies/ml, 73 (95%) had ALT normalization, and 36 of 45 (80%) HBeAg(+) patients had achieved HBe seroconversion. These results were sustained in 24, 85, and 78% of patients, respectively, at the end of follow-up.

At week 48 or EOD, 54 (86%) lamivudine-treated patients with a consolidated response had HBV DNA <300 copies/ml, 62 (98%) had ALT normalization, and 27 of 30 (90%) HBeAg(+) patients had achieved HBe seroconversion. These results were sustained in 17, 63, and 78% of patients, respectively, at the end of follow-up.

Safety

During year 2 of the study, the proportion of entecavir- and lamivudine-treated patients with adverse events was 29% and 23%, respectively. Most of these events were graded as mild and considered to be unrelated to study drug. No entecavir-treated patients had serious adverse events or on-treatment ALT flares during the second year of treatment. In contrast, 5 (3%) lamivudine-treated patients had serious adverse events and 4 (3%) had on-treatment ALT flares.

Among all treated patients through 96 weeks, study treatments were generally well tolerated and the adverse event profiles were generally comparable for entecavir and lamivudine (Table 3). The most common adverse events considered by investigators to be related to treatment with entecavir or lamivudine were fatigue (2% vs. 6%, respectively) and increased serum ALT level (3% vs. 6%, respectively). A total of 11 (4%) entecavir recipients had ALT flares during treatment, and all of these flares were associated with a ≥2 log10 reduction in HBV DNA level. A total of 18 (7%) lamivudine recipients had ALT flares during treatment. Nine of these flares were associated with a ≥2 log10 reduction in HBV DNA level, and 8 were associated with increased HBV DNA. Furthermore, 1 lamivudine recipient had an ALT increase and discontinued therapy at week 3, with no recorded on-treatment HBV DNA.

The proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events during treatment was low and comparable for the two treatment groups (3% and 6% of patients treated with entecavir and lamivudine, respectively). Increased serum ALT level was the most common on-treatment serious adverse event reported in 5 (2%) entecavir recipients and 12 (5%) lamivudine recipients.

During untreated follow-up, the overall frequency of adverse events was 24% among entecavir recipients and 28% among lamivudine recipients. The most common adverse event in this setting was increased serum ALT level occurring in 8% of entecavir-treated and 18% of lamivudine-treated patients. Off-treatment ALT flares were reported in 4 (5%) entecavir recipients and 8 (10%) lamivudine recipients; all but one of these ALT flares occurred in the setting of increased HBV DNA. All ALT flares resolved after restarting alternative HBV treatment or entecavir.

Discussion

We previously presented the results of the 48-week analysis of this study population of nucleoside-naïve Chinese patients with CHB [19]. The results presented here confirm and extend the original 48-week findings, presenting follow-up data for (1) patients who achieved a consolidated response and discontinued therapy; (2) patients who were partial responders and continued in year 2; and (3) an additional analysis evaluating cumulative confirmed responses. Patients who continued or discontinued treatment in year 2 were dependent on response achieved in year 1 and had varied response for each drug. Therefore, no statistical analysis is presented for treatment arms of either cohorts, and results for this cohort are descriptive of what happened to patients who continue or discontinue treatment during the second year.

Among the year 2 cohort, suppression of HBV replication was maintained among patients treated with entecavir but waned in those treated with lamivudine. The proportion of patients with HBV DNA <300 copies/ml by PCR after 48 weeks and at EOD with entecavir was 76% and 74%, respectively, but 52% and 41%, respectively, among those treated with lamivudine.

This same pattern is apparent in the rate of ALT normalization in the year 2 cohort. The proportion of recipients with normal ALT after 48 weeks and at EOD was 91% and 96%, respectively, for entecavir, and 88% and 82%, respectively, for lamivudine.

Among patients initiating treatment with entecavir, 79% had confirmed suppression of HBV DNA replication below the limit of detection (<300 copies/ml by PCR) and 96% had confirmed normalization of ALT (≤1 times ULN) during the trial. These cumulative end points were achieved in 46% and 92% of patients who initiated treatment with lamivudine.

Overall, 240 of 258 (93%) patients who initiated treatment with entecavir had a consolidated or partial response through 96 weeks of follow-up. In contrast, 139 of 261 (53%) patients who initiated treatment with lamivudine had a consolidated or partial response during the study. It is important to comment that the protocol-defined management criteria used in this study (undetectable HBV DNA by bDNA assay and HBeAg loss [instead of seroconversion]) were selected more than 5 years ago and no longer reflect current practice. Therefore, it is possible that off-treatment results may underestimate the durability of responses that would be observed in patients who had achieved undetectable HBV DNA by PCR and had instead a consolidated HBe seroconversion.

Another limitation is that this population was not analyzed for the lamivudine resistance genotype, which may explain the lamivudine results. However, nucleoside-naïve patients have been shown to possess less resistance to entecavir than lamivudine [20]. This may be the product of the rapid, maintained suppression of HBV replication with entecavir, combined with a requirement for multiple substitutions in nucleoside-naïve patients.

These data compare well with that obtained in two large randomized international phase III trials in patients with CHB [14, 15], both of which had similar inclusion and exclusion criteria and management protocols to that of the present study. Among HBeAg(+) patients, 67% of entecavir recipients and 36% of lamivudine recipients had HBV DNA <300 copies/ml after 52 weeks [14]. Patients with a virologic response (<0.7 MEq/ml), who remained HBeAg(+) after 1 year (i.e., partial responders), were eligible to continue therapy for a second year. Through 96 weeks, the cumulative proportion of patients with HBV DNA <300 copies/ml was 80% in those treated with entecavir and 39% in those treated with lamivudine (p < 0.0001) [17]. Similarly, among HBeAg(−) patients, 90% of entecavir recipients and 72% of lamivudine recipients had HBV DNA <300 copies/ml after 52 weeks in a randomized phase III study (p < 0.001) [15]. Although most entecavir- and lamivudine-treated patients discontinued therapy after 52 weeks because of protocol design, the cumulative proportion of patients achieving HBV DNA <300 copies/ml through week 96 was 94% for entecavir-treated and 77% for lamivudine-treated patients (p < 0.0001) [21]. Cumulative proportion of patients with ALT normalization was 89% for entecavir-treated and 84% for lamivudine-treated patients (p > 0.05) [21].

Preliminary results of a small, randomized multicenter viral kinetic study show that treatment with 0.5 mg of entecavir was superior to 10 mg of adefovir for the primary efficacy end point of mean change from baseline in HBV DNA at week 12 [22]. At week 48, mean HBV DNA changes from baseline were −7.28 log10 copies/ml for entecavir as compared with −5.08 log10 copies/ml for adefovir (difference [95% CI]: −1.86 [−2.69, −1.03]), and 58% of entecavir-treated patients as compared with 19% of adefovir-treated patients achieved undetectable HBV DNA (<300 copies/ml) by PCR at week 48 [23].

The short-term differences in potency between entecavir and adefovir would be expected to translate into long-term differences in clinical efficacy, although these two drugs have not been directly compared in a large, long-term study. The mean reduction in HBV DNA at EOD with entecavir in the present study was −6.04 log10 copies/ml. In a separate study, the corresponding decrease in HBV DNA after 2 years of treatment with adefovir in HBeAg(−) patients was −3.47 log10 copies/ml [24]. These data from different studies must be interpreted with caution, but suggest that entecavir provides more profound long-term suppression of HBV DNA replication. If this is the case, then entecavir may be preferred over adefovir as a first-line treatment option for CHB.

Treatment was well tolerated throughout 2 years of therapy, with no substantial differences between entecavir and lamivudine. Fewer ALT flares (on- and off-treatment) were observed with entecavir than with lamivudine. Most ALT flares during treatment with entecavir were associated with reductions in HBV DNA. In contrast, 44% of those that occurred with use of lamivudine were associated with increased HBV DNA.

In conclusion, entecavir provides profound suppression of HBV replication that is durable for a period of at least 2 years in nucleoside-naïve Chinese patients with CHB. In contrast, the efficacy of lamivudine was shown to wane over time. Among those treated with entecavir, the proportion of patients with a consolidated response actually increased in year 2 of treatment. The results of this study confirm and extend the findings of the phase III clinical trial program that has demonstrated superior virologic and biochemical efficacy with entecavir than with lamivudine. Available data suggest that entecavir is a preferred first-line nucleoside analogue for CHB.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HBeAg:

-

Hepatitis B e antigen

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- ULN:

-

Upper limit of normal

References

Schiff ER. Prevention of mortality from hepatitis B and hepatitis C. Lancet 2006;368:896–897

Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Lu SN, et al. REVEAL-HBV Study Group. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA 2006;295:65–73

Iloeje UH, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Chen CJ. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology 2006;130:678–686

Yang HI, Lu SN, Liaw YF, You SL, Sun CA, Wang LY, et al. Taiwan Community-Based Cancer Screening Project Group. Hepatitis B e antigen and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2002;347:168–174

Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, et al. Cirrhosis Asian Lamivudine Multicentre Study Group. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1521–1531

Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, Jacobson IM, Martin P, Schiff ER, et al. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: an update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;4:936–962

Zoulim F. Hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside naïve patients: does it exist? Hepatology 2006;44:1404–1407

Lai CL, Dienstag J, Schiff E, Leung NW, Atkins M, Hunt C, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of YMDD variants during lamivudine therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:687–696

HEPSERA® (adefovir dipivoxil) Package Insert. Gilead Sciences, Inc., 2006

Lai CL, Gane E, Hsu CW, Thongsawat S, Wang Y, Chen Y, et al. Global Study Group. Two-year results from the GLOBE trial in patients with hepatitis B: greater clinical and antiviral efficacy for telbivudine (LdT) vs lamivudine. Presented at the 57th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, 2006 Oct 27–31, Boston, MA

Colonno RJ, Rose RE, Pokornowski K, Baldick CJ, Klesczewski K, Tenney D. Assessment at three years shows high barrier to treated nucleoside naive patients while resistance emergence increases over time in lamivudine refractory patients. Hepatology 2006;44(Suppl 1):229A–230A

Colonno RJ, Rose RE, Pokornowski K, Baldick CJ, Eggers B, Xu D, et al. Bristol-Myers Squibb Research and Development. Four year assessment of ETV resistance in nucleoside-naive and lamivudine refractory patients [abstract 781]. J Hepatol 2007;46(Suppl 1):S294

Colonno RJ, Genovesi EV, Medina I, Lamb L, Durham SK, Huang ML, et al. Long-term entecavir treatment results in sustained antiviral efficacy and prolonged life span in the Woodchuck model of chronic hepatitis infection. J Infect Dis 2001;184:1236–1245

Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, Chao YC, et al. BEHoLD AI463022 Study Group. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1001–1010

Lai CL, Shouval D, Lok AS, Chang TT, Cheinquer H, Goodman Z, et al. BEHoLD AI463027 Study Group. Entecavir versus lamivudine for patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1011–1020

Sherman M, Yurdaydin C, Sollano J, Silva M, Liaw YF, Cianciara J, et al. AI463026 BEHoLD Study Group. Entecavir for treatment of lamivudine-refractory, HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 2006;130:2039–2049

Gish RG, Lok AS, Chang TT, de Man RA, Gadano A, Sollano J, et al. Entecavir therapy up to 96 weeks in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 2007;133:1437–1444

Chang TT, Chao YC, Kaymakoglu S, Cheinquer H, Pessoa M, Gish R, et al. Entecavir maintained virologic suppression through 3 years of treatment in antiviral naive HBeAg(+) patients (ETV 022/901) [abstract 109]. Hepatology 2006;44(Suppl 1):229A

Yao G, Chen C, Lu W, Ren H, Tan D, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of entecavir compared to lamivudine in nucleoside-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B: a randomised double-blind trial in China. Hepatology Int 2007;1:365–372

Colonno RJ, Rose R, Baldick CJ, Levine S, Pokornowski K, Yu CF, et al. Entecavir resistance is rare in nucleoside naïve patients with hepatitis B. Hepatology 2006;44:1656–1665

Shouval D, Akarca US, Hatkjs G, Kitis G, Lai CL, Cheniquer H, et al. Continued virologic and biochemical improvement through 96 week of entecavir treatment in HBeAg(−) chronic hepatitis B patients (Study ETV-027) [abstract 45]. J Hepatol 2006;44(Suppl 2):S21

Leung N, Peng C, Sollano J, Lesmana L, Yuen M, Jeffers L, et al. Entecavir results in higher HBV DNA reduction vs adefovir in chronically infected HBeAg(+) antiviral-naive adults: 24 wk results (E.A.R.L.Y. study) [abstract 982]. Hepatology 2006;44(Suppl 1):554A

Leung N, Peng CY, Sollano J, Lesmana L, Yuen MF, Jeffers L, et al. Entecavir results in higher HBV DNA reduction vs adefovir in chronically infected HBeAg(+) antiviral-naive adults: 48 wk results (E.A.R.L.Y. study) [abstract 49]. J Hepatol 2007;46(Suppl 2):S24

Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang TT, Kitis G, Rizzetto M, et al. Adefovir Dipivoxil 438 Study Group. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2673–2681

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a research grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Presented in part at the 57th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, October 27–31, 2006; the 17th Conference of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver, March 27–31, 2007.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, G., Chen, C., Lu, W. et al. Virologic, serologic, and biochemical outcomes through 2 years of treatment with entecavir and lamivudine in nucleoside-naïve Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B: a randomized, multicenter study. Hepatol Int 2, 486–493 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-008-9088-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-008-9088-8