Abstract

Purpose of review

This review provides an overview of recent developments in the field of eosinophilic gastritis (EG) and eosinophilic duodenitis (EoD) with emphasis on diagnostic criteria, the clinical manifestation and available or emerging treatments.

Recent findings

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases such as EG and EoD are chronic inflammatory conditions with gastrointestinal symptoms and increased density of mucosal eosinophilic cells. Recent data suggest an association between increases of duodenal eosinophils and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia. Eosinophil infiltrates are patchy, and counts fluctuate with seasons, diet, medications and geographic factors. Country-specific reference ranges remain to be defined. Few treatment trials explored symptomatic improvement and resolution of eosinophilic infiltration in functional dyspepsia.

Summary

Eosinophils are part of the physiologic adaptive and innate immune response. A link between EG and in particular EoD with functional dyspepsia has been observed but a causal link with symptoms remains to be established.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction, definitions and epidemiology

Eosinophils are white blood cells involved in the adaptive and innate immune response [1]. They are named eosinophils as staining with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) results in an intense pink colouring of these cells. Eosinophils were initially believed to be relevant for the immune response to parasites. Nowadays, their broad role for the initiation, propagation and resolution of immune responses, including tissue repair, is well established. Eosinophils originate from the bone marrow where they mature before being released into the blood stream. They travel via the blood stream to the destination tissues including the gastrointestinal mucosa where they remain for 1 to 2 weeks. Since eosinophils convey a defence against unwanted interlopers including parasites, they are frequently found in low numbers in gut mucosal samples of apparently healthy subjects [2].

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in eosinophilic gastritis (EG) and eosinophilic duodenitis (EoD). Figure 1 shows a steady increase in research interest in EG and EoD since the 1940s. In spite of this growing attention, most studies are still based on small samples or are simple case studies [3].

In the absence of obvious triggers for and accumulation of eosinophils in mucosal tissue, primary infiltrative eosinophilic disorders of the gut can occur [4]. Diagnosis of these disorders is based on the anatomic distribution of the eosinophil infiltration within the gastrointestinal tract [4]. For eosinophilic diseases such as eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE), EG, EoD, eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) or eosinophilic colitis (EC), histologic diagnosis is required [4]. While many patients presenting with eosinophilic conditions show eosinophilic counts multiple times above the reference range (e.g. in EC), other conditions are reported to present with significant but numerically small changes of eosinophil numbers (e.g. functional dyspepsia and duodenal eosinophilia) [5]. Due to the adaptive nature of eosinophilic cells as part of the immune response to microbial and environmental challenges [6], normal values for eosinophil counts in mucosal tissues may require local validation to account for environmental factors such as general hygiene, climate and subsequent exposure to microbes, variations in diet and exposure to other environmental antigens.

Epidemiology and geographic variation

While epidemiologic data for EG and EoD are limited, based upon health insurance data from the USA, the standardised estimated prevalence rates of eosinophilic gastritis and eosinophilic gastroenteritis are believed to be 6.3/100,000 and 8.4/100,000, respectively [7]. EG and EoD are found in all age groups [8]. Data on gender distribution are controversial. While a higher prevalence in men has been reported [3], this was not confirmed in a large combined paediatric/adult cohort from the USA [9]. Overall, it is highly likely that due to the abovementioned challenges and the still limited awareness of EG and EoD, paired with the heterogeneity of symptomatic presentation and lack of universally accepted or applicable diagnostic criteria, the real prevalence might be substantially higher than reported [10].

Diagnosis of EG and EoD

Symptoms referred to the upper gastrointestinal tract and an increased number of eosinophils in the mucosa of the stomach or duodenum define EG and EoD. To diagnose EG or EoD, it is thus required that the patient has ‘typical’ symptoms and increased tissue eosinophil counts. In addition, other disorders causing the symptoms and mucosal eosinophilic infiltrates (e.g. parasitic infections or systemic immune diseases) need to be ruled out before EG or EoD are diagnosed [11]. However, even in healthy subjects, eosinophil infiltration as a reflection of a physiologic immune response might be observed [12]. Indeed, a variety of factors may influence eosinophil counts. Gastric eosinophil counts are influenced not only by autoimmune processes such as gastritis but also by a concomitant colonisation of the stomach by Helicobacter pylori [13]. Due to the complexity of occurrence of eosinophils, precise cut-offs or normal ranges for eosinophil counts are widely lacking thus far. While gastrointestinal symptoms in combination with increased eosinophil cell counts define EG and EoD, symptoms and clinical presentations are variable, and potentially influenced by the location, severity and depth of infiltration of the mucosa [14].

Since eosinophils are part of the physiologic mucosal immune response, it is conceptionally necessary to define and compare thresholds for ‘normal’ eosinophil counts in healthy asymptomatic subjects with eosinophil counts in patients with suspected EG or EoD rather than confirming presence or absence of eosinophilic cells in the gastric or duodenal mucosa. One study from the USA reported a mean eosinophil count of 8.2 eosinophils per high power field (HPF) with a standard deviation of ± 6.3 in 370 consecutive adults without small intestinal disease. Based upon this, an upper range of the norm was determined to be 20.4 eosinophils/HPF (8.2 + (6.3 × 1.96)) [15•]. Others suggest a mean threshold of eosinophils for EoD of 30 Eos/HPF counted in a minimum of 3 HPF [16]. However, when control groups from cohort studies focussing on the role of duodenal eosinophilia are assessed [15•, 17•, 18, 19•, 20,21,22,23,24, 25•], considerable variation in the mean cell counts per HPF are found. Figure 1 depicts the mean eosinophil count per HPF found in controls of recent studies comparing patients with FD with controls. The mean eosinophil number of the control groups was found to be highly variable and ranged from < 5 per HPF to > 40 HPF. These studies also highlighted that not only the number of eosinophils was increased in patients with FD but eosinophils in FD patients had a higher proportion of activated eosinophils with degranulation [25•]. In this context, it is not only important to emphasise that ‘normal’ eosinophil counts are highly variable in controls, but one study compared subjects without intestinal disease with subjects with elevated eosinophil counts and did not find a link between increased eosinophil counts and specific gastrointestinal symptoms [15•]. This may not only present a significant challenge regarding the development of ‘normal’ values for duodenal eosinophil that guide diagnosis and assessment of treatment response but raise the question if additional criteria are required to establish eosinophil-related dyspepsia. It is possible that high eosinophil counts (with or without degranulation) only play a role for the manifestation of dyspeptic symptoms in patients with otherwise unexplained symptoms if there are other factors such as altered gut-brain interaction that facilitate manifestation of the gut-related symptoms. Thus, the current concept of increased eosinophils as the causal factor for symptoms in patients with otherwise unexplained (functional) dyspepsia needs to be complemented by a multicomponent pathophysiologic model, whereby increased eosinophils are one factor (or potentially an indicator for the presence of any kind of inflammatory stimulus) and it seems likely symptoms manifest only in the presence of other ‘permissive’ factor(s).

Obviously, there is huge variation in the mean eosinophil counts. No standard pathological approach has been published and endorsed. This presents a major challenge when globally acceptable thresholds for reference ranges need to be established (Fig. 1). Considering these variations, thresholds to diagnose EG or EoD need to be viewed with caution. A large number of factors influence eosinophil counts that include widely used proton pump inhibitors [17•], diet [26] or even seasonal variation [27•]. Thus, interpretation and diagnoses of EG and EoD require caution if cell counts are only modestly elevated and potential confounders carefully considered. To complicate matters, some investigators seek HPF with clusters of eosinophils and report these ‘peak’ numbers of eosinophils in selected sections [28] and report these peak numbers. This may potentially introduce a bias for clinical studies when different cohorts or interventions are compared, and the pathologist is not blinded for group or intervention.

To overcome the barriers of a tissue-based diagnosis, a recent study [29] utilising samples from nearly 400 paediatric and adult patients with EG aimed to develop a diagnostic test based upon the expression of a panel of 18 dysregulated genes and blood EG scores derived from dysregulated cytokine/chemokine levels. The authors observed robust associations between specific gastric molecular profiles and histologic and endoscopic features. This may point towards an opportunity to develop in the future blood-based markers for the disease, and biopsy in combination with blood samples may provide a more reliable diagnosis for EG.

Interval between manifestation of symptoms and diagnosis of EG or EoD

Since the diagnosis of EG and EoD is based upon the histologic verification of increased eosinophil counts in the mucosa, endoscopy is required to obtain tissue from potentially affected organs. This may present a barrier to timely diagnosis and a recent study [30] revealed that the mean interval between symptom manifestation and diagnosis was 3.6 years. Besides delays in relation to diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy, the failure to collect biopsy specimens for histologic evaluation when an endoscopy actually was performed contributed to the delay. This highlights the need to consider EG and EoD early as differential diagnosis of chronic unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms. In the above study [30], predictors for a more than 2-year diagnostic delay included adult age, a previous diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome or functional dyspepsia, or gastric/peptic ulcer.

Endoscopic findings in eosinophilic gastritis or duodenitis

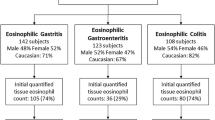

The diagnosis of EG, EoD or EGE, and eosinophilic colitis (EC) is based upon the histologic verification of increased eosinophil counts and thus far no specific endoscopic features for EGE has been reported from a large retrospective cohort of 317 children and 56 adults from the USA [31]. Indeed, most patients had normal endoscopic appearance of the respective regions of the GI tract and patients could have been categorised as a functional gastrointestinal disorder if histology would not have revealed the increased eosinophils.

Risk factors for EG and EoD

Defining risk factors for the development of EG and EoD is key to understanding the epidemiology of eosinophilic disorders of the gastrointestinal tract and ultimately prevent the manifestation of these conditions. Data for EG and EoD is very limited, but risk factors have been studied for eosinophilic oesophagitis that can overlap with more distal gut eosinophilia [32]. Population density and climate have been proposed confounders [33]. A negative correlation has been shown between population density and risk of EoE when rural and urban areas were compared to metropolitan areas [34]. In addition, cold climate zones are associated with increasing odds of EoE compared with tropical and arid zones [35].

Gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with EG and EoD

The most common reported symptoms are nausea/vomiting and abdominal pain [9, 36]. Other gastrointestinal symptoms reported by patients with EG or EoD are diarrhoea (potentially due to concomitant manifestation of eosinophilia in the small intestine or colon) and early satiety [5]. Thus, symptoms in patients with EG and EoD may not be different from patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders and in particular functional dyspepsia. Recently, several studies reported the association between increased duodenal eosinophils and symptoms of FD [15•, 17•, 18, 19•, 20,21,22,23,24, 25•]. As described above, the mean eosinophil number of the control groups were highly variable in frequent studies with considerable seasonal fluctuation. This may only present a significant challenge regarding the development of globally acceptable ‘normal’ values for duodenal eosinophils that guide diagnosis and assessment of treatment response. Ultimately, this would require that for all regions, locally validated diagnostic criteria with relevant eosinophil thresholds are developed.

Psychological manifestations in patients with EG and EoD

A recent study reported higher degranulation levels of eosinophils in patients with diarrhoea dominant irritable bowel syndrome compared to healthy controls with an increased content of CORTICOTROPIN-releasing factor in the cytoplasmic granules [37]. This degranulation was linked not only to the clinical severity of the GI symptoms, but also to life stress and depression. Similarly, in another study, anxiety was associated with eosinophilia in the second part of the duodenum [19•]. This is consistent with the concept that the inflammatory process that is reflected by eosinophil infiltration has systemic effects, and these effects of inflammatory mediators have been shown to influence brain function [38]. Indeed, patients with EG or EoD frequently report symptoms that resemble symptoms of patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders or patients with (mild) inflammatory bowel disease. In these patients, an increased prevalence of psychological disorders is clinically observed [39, 40]. Previous work has suggested a link between immune activation and psychologic comorbidities in patients with IBS [41], while psychological stress may augmented post-inflammatory visceral hyperalgesia [42] and thus may contribute to severity of symptoms and ultimately to health care seeking. The chronic GI symptoms experienced by patients with EG and EoD adversely affect impact quality of life and psychological functioning in both adult and children [36]. While research in psychological functioning and EG/EoD is limited, EoE is more widely studied and shows high rates of psychological co-morbidity, especially depression and anxiety [36, 43]. Thus far, it is unknown if the localised inflammatory process reflected by EG and EoD per se is associated with mood disorders or the reported increased prevalence is reactive and simply a reflection of the impaired quality of life. Alternatively, specific personality traits such as anxiety and depression may be linked to altered brain-gut interactions and thus may facilitate the manifestation and subsequent health care seeking of patients with EG and EoD.

Differential diagnosis for mucosal eosinophilia

A variety of conditions are associated with mucosal eosinophilia including food allergy, parasitic or bacterial infections, inflammatory bowel disorders, drug reactions or autoimmune disorders [11]. An increase of eosinophils in the gastrointestinal tract may occur as an allergic reaction to certain foods. While food allergy and food intolerance (non-allergic food hypersensitivities) need to be differentiated, hypersensitivity/allergy is an adverse immunologic reaction that can be due to IgE- or non-IgE-mediated immune mechanisms resulting in increased eosinophil counts [44].

Treatment approaches

A variety of treatments appear to be effective to normalise eosinophilic tissue counts. These interventions include diet, proton pump inhibitors or immune modulators including steroids [45]. While elimination diets are considered effective in the short term, they may substantially impact on the patient’s quality of life [46]. Thus, many patients will only consider them a short-term intervention unless specific food triggers are identified. Therefore, stepwise re-introduction of a ‘normal’ diet is critical for the long-term management of patients. Unfortunately, there is limited evidence to guide this stepwise re-introduction of the normal diet [45]. At present, a frequently used, but poorly validated, approach is to group foods according to a potential allergic risk and re-introduce starting with the food components rated as having the lowest risk.

While systemic corticosteroids are effective, they may have long-term adverse effects. Topical steroids such as budesonide that undergo first-pass inactivation after intestinal absorption are another potential treatment approach [47]. In a recent small prospective, randomised placebo-controlled study [48••], the topical steroid budesonide was tested in FD patients with increased eosinophil counts. In this setting, a reduction in duodenal eosinophils from baseline to post-treatment was significantly correlated with a reduction in diary-reported symptoms of postprandial fullness and severity of early satiety. However, no difference between active medication and placebo was found. While the association between eosinophils and symptoms was encouraging, this can be seen as confirmation of a potential link between mucosal eosinophils and specific FD symptoms. On the other hand, failure of the immunomodulatory active therapy might have been due to a type-2 error, or it might suggest that the increase of the eosinophils is simply the reflection of an immune response to for example an infectious agent.

Alternative treatments are under development. Anti-Siglec-8 antibody has been shown in animal studies to deplete eosinophils and inhibit mast cells and thus might be an effective treatment for eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis [49]. Recent studies suggest that this Anti-Siglec-8 Antibody led to significant reduction in eosinophil counts and symptoms for patients with eosinophilic gastritis and eosinophilic duodenitis or both [50, 51].

Conclusions

The diagnosis of EG and EoD is based on the clinical presentation with GI symptoms referred to the upper gut and the histologic confirmation that eosinophil counts are increased in the stomach and/or in the duodenum. It is rare to find eosinophil counts multi-fold increased compared to asymptomatic controls. Recent studies have proposed a link between functional dyspepsia and duodenal eosinophilia, but the studies are characterised by small increases (on average 10–40%) of eosinophil numbers. Similar changes in the eosinophilic densities may occur due to geographic, seasonal or dietary changes, and there are substantial differences in the mean eosinophil counts reported for the control groups in recent studies exploring the link between functional dyspepsia and eosinophils. Due to the adaptive nature of eosinophilic cells as part of the immune response to environmental challenges, normal values for eosinophil counts in mucosal tissues may require local validation to account for environmental factors. The unanswered question is what antigens may drive increased intestinal eosinophilia in functional dyspepsia; foods and infections have both been implicated. Further, the exact nature of the immune activation in the setting of duodenal eosinophilia remains to be identified. The emerging concept that increased eosinophils may be a causal factor for symptoms in patients with otherwise unexplained (functional) dyspepsia is exciting. However, it might not be the number of eosinophils (which varies greatly) but rather degranulation and release of damaging contents, such as major basic protein, which in turn leads to increased permeability and neural damage that is important. Furthermore, the considerable variability of eosinophil counts in asymptomatic controls in studies conducted in various geographic regions of the world may present a challenge to ascertain a direct relationship between eosinophil numbers and symptoms.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Travers J, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophils in mucosal immune responses. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8(3):464–75.

Blanchard C, Rothenberg ME. Biology of the eosinophil. Adv Immunol. 2009;101:81–121.

Zhang M, Li Y. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a state-of-the-art review: eosinophilic gastroenteritis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32(1):64–72.

Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y, Schoepfer A. Eosinophilic esophagitis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and eosinophilic colitis: common mechanisms and differences between east and west. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2016;1(2):63–9.

Walker MM, Salehian SS, Murray CE, Rajendran A, Hoare JM, Negus R, et al. Implications of eosinophilia in the normal duodenal biopsy - an association with allergy and functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(11):1229–36.

Gurtner A, Gonzalez-Perez I, Arnold IC. Intestinal eosinophils, homeostasis and response to bacterial intrusion. Semin Immunopathol. 2021;43(3):295–306.

Jensen ET, Martin CF, Kappelman MD, Dellon ES. Prevalence of eosinophilic gastritis, gastroenteritis, and colitis: estimates from a national administrative database. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62(1):36–42.

Memon RJ, Savliwala MN. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Treasure Island: StatPearls; 2021.

Pesek RD, Reed CC, Muir AB, Fulkerson PC, Menard-Katcher C, Falk GW, et al. Increasing rates of diagnosis, substantial co-occurrence, and variable treatment patterns of eosinophilic gastritis, gastroenteritis, and colitis based on 10-year data across a multicenter consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):984–94.

Chehade M, Kamboj AP, Atkins D, Gehman LT. Diagnostic delay in patients with eosinophilic gastritis and/or duodenitis: a population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(5):2050-9.e20.

Collins MH, Capocelli K, Yang G-Y. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders pathology. Front Med. 2018;4:261.

Yantiss RK. Eosinophils in the GI tract: how many is too many and what do they mean? Mod Pathol. 2015;28(Suppl 1):S7-21.

Bettington M, Brown I. Autoimmune gastritis: novel clues to histological diagnosis. Pathology. 2013;45(2):145–9.

Sunkara T, Rawla P, Yarlagadda KS, Gaduputi V. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: diagnosis and clinical perspectives. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2019;12:239–53.

Genta RM, Sonnenberg A, Turner K. Quantification of the duodenal eosinophil content in adults: a necessary step for an evidence-based diagnosis of duodenal eosinophilia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47(8):1143–50. Large study that suggest based upon US data a cutoff count of 20 eos/hpf would be useful to separate patients with normal from those with elevated duodenal eosinophilic infiltrations. The clinical implications of duodenal eosinophilia, particularly when it is not an expression of eosinophilic gastroenteritis, remain to be established.

Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Rothenberg ME, Hirano I, Chehade M, Peterson KA, Falk GW, Murray JA, Gehman LT, Chang AT, Singh B, Rasmussen HS, Genta RM. Determination of biopsy yield that optimally detects eosinophilic gastritis and/or duodenitis in a randomized trial of lirentelimab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):535–45.e15.

Wauters L, Ceulemans M, Frings D, Lambaerts M, Accarie A, Toth J, et al. Proton pump inhibitors reduce duodenal eosinophilia, mast cells, and permeability in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(5):1521-31.e9. Landmark study showing eosinophil-reducing effects as a therapeutic mechanism of PPIs in FD, with differential effects in healthy volunteers pointing to a role of luminal changes.

Lee MJ, Jung H-K, Lee KE, Mun Y-C, Park S. Degranulated eosinophils contain more fine nerve fibers in the duodenal mucosa of patients with functional dyspepsia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25(2):212–21.

Ronkainen J, Aro P, Walker MM, Agréus L, Johansson SE, Jones M, et al. Duodenal eosinophilia is associated with functional dyspepsia and new onset gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50(1):24–32. Landmark study on the association between duodenal eosinophilia and functional dyspepsia. Duodenal eosinophilia is a risk factor risk of GERD in subjects with functional dyspepsia.

Wauters L, Nightingale S, Talley NJ, Sulaiman B, Walker MM. Functional dyspepsia is associated with duodenal eosinophilia in an Australian paediatric cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(10):1358–64.

Taki M, Oshima T, Li M, Sei H, Tozawa K, Tomita T, et al. Duodenal low-grade inflammation and expression of tight junction proteins in functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(10):e13576.

Wang X, Li X, Ge W, Huang J, Li G, Cong Y, et al. Quantitative evaluation of duodenal eosinophils and mast cells in adult patients with functional dyspepsia. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015;19(2):50–6.

Sarkar MAM, Akhter S, Khan MR, Saha M, Roy PK. Association of duodenal eosinophilia with Helicobacter pylori-negative functional dyspepsia. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2020;21(1):19–23.

Chaudhari AA, Rane SR, Jadhav MV. Histomorphological spectrum of duodenal pathology in functional dyspepsia patients. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(6):ec01-ec4.

Vanheel H, Vicario M, Boesmans W, Vanuytsel T, Salvo-Romero E, Tack J, et al. Activation of eosinophils and mast cells in functional dyspepsia: an ultrastructural evaluation. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5383. Landmark study showing that eosinophil and mast cell activation play a role in the pathophysiology of FD.

Higuchi T, Tokunaga M, Murai T, Takeuchi K, Nakayama Y. Elemental diet therapy for eosinophilic gastroenteritis and dietary habits. Pediatrics International. 2022;64(1):e14894.

Järbrink-Sehgal ME, Sparkman J, Damron A, Walker MM, Green LK, Rosen DG, Graham DY, El-Serag HE. Functional dyspepsia and duodenal eosinophil count and degranulation: a multiethnic US veteran cohort study. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(10):3482–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06689-2. Landmark study duodenal eosinophilic degranulation, an activated eosinophil marker, was significantly associated with FD, especially early satiety.

Stucke EM, Clarridge KE, Collins MH, Henderson CJ, Martin LJ, Rothenberg ME. Value of an additional review for eosinophil quantification in esophageal biopsies. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61(1):65–8.

Shoda T, Wen T, Caldwell JM, Collins MH, Besse JA, Osswald GA, et al. Molecular, endoscopic, histologic, and circulating biomarker-based diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis: Multi-site study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):255–69.

Chehade M, Kamboj AP, Atkins D, Gehman LT. Diagnostic delay in patients with eosinophilic gastritis and/or duodenitis: a population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;9(5):2050-9.e20.

Pesek RD, Reed CC, Collins MH, Muir AB, Fulkerson PC, Menard-Katcher C, et al. Association between endoscopic and histologic findings in a multicenter retrospective cohort of patients with non-esophageal eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(7):2024–35.

Prussin C. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis and related eosinophilic disorders. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43(2):317–27.

Yantiss RK. Eosinophils in the GI tract: How many is too many and what do they mean? Mod Pathol. 2015;28(1):S7–21.

Jensen ET, Hoffman K, Shaheen NJ, Genta RM, Dellon ES. Esophageal eosinophilia is increased in rural areas with low population density: results from a national pathology database. Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol. 2014;109(5):668–75.

Hurrell JM, Genta RM, Dellon ES. Prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia varies by climate zone in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(5):698–706.

Taft TH, Guadagnoli L, Edlynn E. Anxiety and depression in eosinophilic esophagitis: a scoping review and recommendations for future research. J Asthma Allergy. 2019;12:389–99.

Salvo-Romero E, Martínez C, Lobo B, Rodiño-Janeiro BK, Pigrau M, Sánchez-Chardi AD, et al. Overexpression of corticotropin-releasing factor in intestinal mucosal eosinophils is associated with clinical severity in Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):20706.

Gray MA, Chao CY, Staudacher HM, Kolosky NA, Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Anti-TNFα therapy in IBD alters brain activity reflecting visceral sensory function and cognitive-affective biases. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0193542.

Bryant RV, van Langenberg DR, Holtmann GJ, Andrews JM. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in inflammatory bowel disease: impact on quality of life and psychological status. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(5):916–23.

Mikocka-Walus A, Turnbull D, Moulding N, Wilson I, Andrews JM, Holtmann G. Psychological comorbidity and complexity of gastrointestinal symptoms in clinically diagnosed irritable bowel syndrome patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(7 Pt 1):1137–43.

Liebregts T, Adam B, Bredack C, Röth A, Heinzel S, Lester S, et al. Immune activation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(3):913–20.

Liebregts T, Adam B, Bertel A, Lackner C, Neumann J, Talley NJ, et al. Psychological stress and the severity of post-inflammatory visceral hyperalgesia. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(2):216–22.

de Rooij WE, BennebroekEvertsz F, Lei A, Bredenoord AJ. Mental distress among adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;2020:e14069.

Bischoff SC. Food allergy and eosinophilic gastroenteritis and colitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10(3):238–45.

Madison JM, Bhardwaj V, Braskett M. Strategy for food reintroduction following empiric elimination and elemental dietary therapy in the treatment of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(5):25.

Chen JW. Management of eosinophilic esophagitis: dietary and nondietary approaches. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020;35(5):835–47.

Edsbäcker S, Andersson T. Pharmacokinetics of budesonide (Entocort EC) capsules for Crohn’s disease. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(12):803–21.

Talley NJ, Walker MM, Jones M, Keely S, Koloski N, Cameron R, et al. Letter: budesonide for functional dyspepsia with duodenal eosinophilia—randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel-group trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53(12):1332–3. Small propsective, randomised-placebo controlled study testing a topical steroid. While overtime improvement of symptoms and reduction of eosinophil counts occurred, placebo and active were not statistically different. Larger trials needed.

Youngblood BA, Brock EC, Leung J, Falahati R, Bryce PJ, Bright J, et al. AK002, A humanized sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin-8 antibody that induces antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against human eosinophils and inhibits mast cell-mediated anaphylaxis in mice. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;180(2):91–102.

Dellon ES, Peterson KA, Murray JA, Falk GW, Gonsalves N, Chehade M, et al. Anti–Siglec-8 antibody for eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(17):1624–34.

Peterson KA, Chehade M, Murray JA, Falk GW, Gonsalves N, Genta RM, et al. 539 Long-term tretament of patients with eosinophilic gastritis and/or eosinophilic duodenituis with lirentelimab, a monoclonal antoibody againts SIGLEC 8. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):S-111.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Sarah Ollsson declares no conflict of interest. Gerald Holtmann reports to be on the advisory boards Australian Biotherapeutics, Glutagen, Bayer, and received research support from Bayer, Abbott, Pfizer, Janssen, Takeda and Allergan. He serves on the Boards of the West Moreton Hospital and Health Service, Queensland; UQ Healthcare, Brisbane; and the Gastro-Liga, Germany and the advisory Board of Servatus. He has a patent for the Brisbane aseptic biopsy device and serves as Editor of the Gastro-Liga Newsletter. GH acknowledges funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) for the Centre for Research Excellence in Digestive Health. GH holds an NHMRC Ideas and one MRFF grant. Nicholas J. Talley reports personal fees from Allakos, from Aviro Health, from Antara Life Sciences, from Arlyx from Bayer, from Danone, from Planet Innovation, from Takeda, from Viscera Labs, from twoXAR, from Viscera Labs, from Dr Falk Pharma, from Censa, from Cadila Pharmaceuticals, from Progenity Inc., from Sanofi-Aventis, from Glutagen, from ARENA Pharmaceuticals, from IsoThrive, from BluMaiden, and from HVN National Science Challenge, and non-financial support from HVN National Science Challenge NZ, outside the submitted work; in addition, NJT has a patent Biomarkers of IBS licenced (no. 12735358.9–1405/2710383 and (no. 12735358.9–1405/2710384), a patent Licensing Questionnaires Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire licenced to Mayo/Talley, a patent Nestec European Patent licenced and a patent Singapore Provisional Patent NTU Ref: TD/129/17 “Microbiota Modulation Of BDNF Tissue Repair Pathway” issued and copyright Nepean Dyspepsia Index (NDI) 1998 and Editorial: Medical Journal of Australia (Editor in Chief), Up to Date (Section Editor), Precision and Future Medicine, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, South Korea, Med (Journal of Cell Press). NJT participates in committees: Australian Medical Council (AMC) Council Member (2016–2019), MBS Review Taskforce (2016–2020), NHMRC Principal Committee, Research Committee (2016–2021), Asia Pacific Association of Medical Journal Editors (APAME) (current), GESA Board Member (2017–2019). NJT Misc: Avant Foundation (judging of research grants) (2019). NJT community and patient advocacy groups: Advisory Board, IFFGD (International Foundation for Functional GI Disorders). NJT acknowledges funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) for the Centre for Research Excellence in Digestive Health. NJT holds an NHMRC Investigator grant.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Olsson, S., Talley, N.J. & Holtmann, G. Eosinophilic Gastritis and Eosinophilic Duodenitis. Curr Treat Options Gastro 20, 501–511 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-022-00392-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-022-00392-z