Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common musculoskeletal disease, affecting nearly 25 % of the world population (WHO reports), leading to pain and disability. There are as yet no clinically proven therapies to halt OA onset or progression; the development of such therapies is, therefore, a national as well as international research priority. Obesity-related metabolic syndrome has been identified as the most significant, but also an entirely preventable risk factor for OA; however, the mechanisms underlying this link remain unclear. We have examined the available literature linking OA and metabolic syndrome. The two conditions have a shared pathogenesis in which chronic low-grade inflammation of affected tissues is recognized as a major factor that is associated with systemic inflammation. In addition, the occurrence of metabolic syndrome appears to alter systemic and local pro-inflammatory cytokines that are also related to the development of OA-like pathologies. Recent findings highlight the importance not only of the elevated number of macrophage in inflamed synovium but also the activation and amplification of the inflammatory state and other pathological changes. The role of local inflammation on the synovium is now considered to be a pharmacological target against which to aim disease-modifying drugs. In this review, we evaluate evidence linking OA, synovitis and metabolic syndrome and discuss the merits of targeting macrophage activation as a valid treatment option for OA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

Three dimensional

- ACC:

-

Articular chondrocytes

- ADAMTS:

-

A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs

- AGEs:

-

Advanced glycation end products

- cDNA:

-

Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid

- COL-2A:

-

Collagen type II

- COL10-A:

-

Collagen type X

- COX-2:

-

Cyclooxygenase-2

- ECM:

-

Extracellular matrix

- FACS:

-

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- GAG:

-

Glycosaminoglycan

- IGF-1:

-

Insulin-like growth factor-1

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- LTs:

-

Leukotrienes

- LTA4 :

-

Leukotriene A4

- LTB4:

-

Leukotriene B4

- Ltb4r1 (BLT1):

-

High-affinity LTB4 receptor 1

- MetS:

-

Metabolic syndrome

- MMP:

-

Matrix metalloproteinase

- mRNA:

-

Messenger ribonucleic acid

- NDAIDs:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- NF-kB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- PD:

-

Protectin

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- RAGE:

-

Receptors for AGE

- RvD:

-

D-series resolvin

- RvE:

-

E-series resolvin

- RUNX:

-

Runt-related transcription factor

- SOX:

-

SRY-related HMG-box

- TGF:

-

Transforming growth factor

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

AIHW. Osteoarthritis: musculoskeletal fact sheet. Arthritis SERIES 2015; 22(phe 186).

Bijlsma JW, Berenbaum F, Lafeber FP. Osteoarthritis: an update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2115–26.

Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(5):778–99.

Stambough JB, Clohisy JC, Barrack RL, et al. Increased risk of failure following revision total knee replacement in patients aged 55 years and younger. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(12):1657–62.

Julin J, Jamsen E, Puolakka T, et al. Younger age increases the risk of early prosthesis failure following primary total knee replacement for osteoarthritis. A follow-up study of 32,019 total knee replacements in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(4):413–9.

Harding PA, Holland AE, Hinman RS, et al. Physical activity perceptions and beliefs following total hip and knee arthroplasty: a qualitative study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2015;31(2):107–13.

Leardini G, Salaffi F, Caporali R, et al. Direct and indirect costs of osteoarthritis of the knee. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22(6):699–706.

Nuesch E, Dieppe P, Reichenbach S, et al. All cause and disease specific mortality in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d1165.

Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):355–69.

Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(8):635–46.

Puenpatom RA, Victor TW. Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in individuals with osteoarthritis: an analysis of NHANES III data. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(6):9–20.

Zhuo Q, Yang W, Chen J, et al. Metabolic syndrome meets osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8(12):729–37. A review of relationship between metabolic syndrome and osteoarthritis.

Vlad SC, Neogi T, Aliabadi P, et al. No association between markers of inflammation and osteoarthritis of the hands and knees. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(8):1665–70.

Smith MD, Chandran G, Parker A, et al. Synovial membrane cytokine profiles in reactive arthritis secondary to intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(4):752–8.

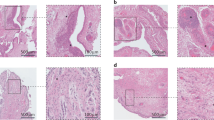

Loeuille D, Chary-Valckenaere I, Champigneulle J, et al. Macroscopic and microscopic features of synovial membrane inflammation in the osteoarthritic knee: correlating magnetic resonance imaging findings with disease severity. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3492–501.

Hamada D, Maynard R, Schott E, et al. Insulin suppresses TNF-dependent early osteoarthritic changes associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015. A research article indicates that the protective and anti-inflammatory role of insulin in the synovium.

Messier SP, Gutekunst DJ, Davis C, et al. Weight loss reduces knee-joint loads in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2026–32.

Sturmer T, Gunther KP, Brenner H. Obesity, overweight and patterns of osteoarthritis: the Ulm Osteoarthritis Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(3):307–13.

Anderson JJ, Felson DT. Factors associated with osteoarthritis of the knee in the first national Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HANES I). Evidence for an association with overweight, race, and physical demands of work. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128(1):179–89.

Berenbaum F, Sellam J. Obesity and osteoarthritis: what are the links? Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75(6):667–8.

Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG, et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2008;59(9):1207–13.

Felson DT, Chaisson CE. Understanding the relationship between body weight and osteoarthritis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1997;11(4):671–81.

Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(12):1145–55.

Millward-Sadler S, Salter DM. Integrin-dependent signal cascades in chondrocyte mechanotransduction. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32(3):435–46.

Chowdhury TT, Akanji OO, Salter DM, et al. Dynamic compression influences interleukin-1beta-induced nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 release by articular chondrocytes via alterations in iNOS and COX-2 expression. Biorheology. 2008;45(3–4):257–74.

Forsyth CB, Cole A, Murphy G, et al. Increased matrix metalloproteinase-13 production with aging by human articular chondrocytes in response to catabolic stimuli. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(9):1118–24.

Gabay O, Gosset M, Levy A, et al. Stress-induced signaling pathways in hyalin chondrocytes: inhibition by Avocado-Soybean Unsaponifiables (ASU). Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008;16(3):373–84.

Yusuf E, Nelissen RG, Ioan-Facsinay A, et al. Association between weight or body mass index and hand osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(4):761–5.

Yusuf E, Ioan-Facsinay A, Bijsterbosch J, et al. Association between leptin, adiponectin and resistin and long-term progression of hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(7):1282–4.

Osborn O, Olefsky JM. The cellular and signaling networks linking the immune system and metabolism in disease. Nat Med. 2012;18(3):363–74.

Stienstra R, Tack CJ, Kanneganti TD, et al. The inflammasome puts obesity in the danger zone. Cell Metab. 2012;15(1):10–8.

Kershaw EE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2004;89(6):2548–56.

Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(1):175–84.

Dumond H, Presle N, Terlain B, et al. Evidence for a key role of leptin in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(11):3118–29.

Pottie P, Presle N, Terlain B, et al. Obesity and osteoarthritis: more complex than predicted! Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(11):1403–5.

Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, Clockaerts S, Feijt C, et al. Infrapatellar fat pad of patients with end-stage osteoarthritis inhibits catabolic mediators in cartilage. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(2):288–94.

Dumond H, Presle N, Terlain B, et al. Evidence for a key role of leptin in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(11):3118–29.

Simopoulou T, Malizos K, Iliopoulos D, et al. Differential expression of leptin and leptin’s receptor isoform (Ob-Rb) mRNA between advanced and minimally affected osteoarthritic cartilage; effect on cartilage metabolism. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15(8):872–83.

Fantuzzi G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(5):911–9.

Poonpet T, Honsawek S. Adipokines: biomarkers for osteoarthritis? World J Orthop. 2014;5(3):319.

Chen T-H, Chen L, Hsieh M-S, et al. Evidence for a protective role for adiponectin in osteoarthritis. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Mol Basis Dis. 2006;1762(8):711–8.

Ehling A, Schäffler A, Herfarth H, et al. The potential of adiponectin in driving arthritis. J Immunol. 2006;176(7):4468–78.

Alshehri AM. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. J Fam Commun Med. 2010;17(2):73–8.

Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128(1):92–105.

Giunta B, Fernandez F, Nikolic WV, et al. Inflammaging as a prodrome to Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5(51):2094–5.

Mobasheri A, Vannucci S, Bondy C, et al. Glucose transport and metabolism in chondrocytes: a key to understanding chondrogenesis, skeletal development and cartilage degradation in osteoarthritis. 2002.

Rosa SC, Gonçalves J, Judas F, et al. Impaired glucose transporter-1 degradation and increased glucose transport and oxidative stress in response to high glucose in chondrocytes from osteoarthritic versus normal human cartilage. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(3):R80.

Bruckbauer A, Zemel MB, Thorpe T, et al. Synergistic effects of leucine and resveratrol on insulin sensitivity and fat metabolism in adipocytes and mice. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2012;9(1):77.

Loeser RF. Aging and osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(5):492.

Rosa SC, Rufino AT, Judas FM, et al. Role of glucose as a modulator of anabolic and catabolic gene expression in normal and osteoarthritic human chondrocytes. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112(10):2813–24.

Stürmer T, Sun Y, Sauerland S, et al. Serum cholesterol and osteoarthritis. The baseline examination of the Ulm Osteoarthritis Study. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(9):1827–32.

Hart DJ, Doyle DV, Spector TD. Association between metabolic factors and knee osteoarthritis in women: the Chingford Study. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(6):1118–23.

Oliviero F, Lo Nigro A, Bernardi D, et al. A comparative study of serum and synovial fluid lipoprotein levels in patients with various arthritides. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413(1–2):303–7.

Faraj M, Messier L, Bastard JP, et al. Apolipoprotein B: a predictor of inflammatory status in postmenopausal overweight and obese women. Diabetologia. 2006;49(7):1637–46.

Davies-Tuck ML, Hanna F, Davis SR, et al. Total cholesterol and triglycerides are associated with the development of new bone marrow lesions in asymptomatic middle-aged women—a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(6):R181. doi:10.1186/ar2873.

Gierman LM, Kuhnast S, Koudijs A, et al. Osteoarthritis development is induced by increased dietary cholesterol and can be inhibited by atorvastatin in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice—a translational model for atherosclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013.

Tiku ML, Shah R, Allison GT. Evidence linking chondrocyte lipid peroxidation to cartilage matrix protein degradation possible role in cartilage aging and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(26):20069–76.

Whigham LD, Cook EB, Stahl JL, et al. CLA reduces antigen-induced histamine and PGE(2) release from sensitized guinea pig tracheae. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280(3):R908–12.

Shen C-L, Dunn DM, Henry JH, et al. Decreased production of inflammatory mediators in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes by conjugated linoleic acids. Lipids. 2004;39(2):161–6.

Singh G, Miller JD, Lee FH, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among US adults with self-reported osteoarthritis: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8(15 Suppl):S383–91.

Dahaghin S, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Koes BW, et al. Do metabolic factors add to the effect of overweight on hand osteoarthritis? The Rotterdam Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):916–20.

Dedier J, Stampfer MJ, Hankinson SE, et al. Nonnarcotic analgesic use and the risk of hypertension in US women. Hypertension. 2002;40(5):604–8.

Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rosner B, et al. Frequency of analgesic use and risk of hypertension in younger women. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(19):2204–8.

Verdecchia P, Angeli F, Mazzotta G, et al. Treatment strategies for osteoarthritis patients with pain and hypertension. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2010;2(4):229–40.

Findlay D. Vascular pathology and osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2007;46(12):1763–8.

Firestein GS, Budd R, O’Dell JR, et al., Kelley’s textbook of rheumatology. 2012: Saunders.

Smith M, Barg E, Weedon H, et al. Microarchitecture and protective mechanisms in synovial tissue from clinically and arthroscopically normal knee joints. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(4):303–7.

Smith MD. The normal synovium. Open Rheumatol J. 2011;5:100–6.

Barland P, Novikoff AB, Hamerman D. Electron microscopy of the human synovial membrane. J Cell Biol. 1962;14(2):207–20.

Athanasou NA. Synovial macrophages. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(5):392–4.

Edwards J. The nature and origins of synovium: experimental approaches to the study of synoviocyte differentiation. J Anat. 1994;184(Pt 3):493.

Lau SK, Chu PG, Weiss LM. CD163 A specific marker of macrophages in paraffin-embedded tissue samples. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122(5):794–801.

Athanasou N, Quinn J. Immunocytochemical analysis of human synovial lining cells: phenotypic relation to other marrow derived cells. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50(5):311–5.

Athanasou NA, Quinn J, Heryet A, et al. The immunohistology of synovial lining cells in normal and inflamed synovium. J Pathol. 1988;155(2):133–42.

Qu Z, Garcia CH, O’Rourke LM, et al. Local proliferation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes contributes to synovial hyperplasia. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37(2):212–20.

Wright V, Dowson D, and Kerr J. The structure of joints. In International review of connective tissue research. Academic Press Inc New York 1973; pp. 105–125.

Levick JR, McDonald JN. Fluid movement across synovium in healthy joints: role of synovial fluid macromolecules. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(5):417–23.

Musumeci G, Loreto C, Carnazza ML, et al. Acute injury affects lubricin expression in knee menisci: an immunohistochemical study. Ann Anat. 2013;195(2):151–8.

Sandell LJ, Aigner T. Articular cartilage and changes in arthritis. An introduction: cell biology of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res. 2001;3(2):107–13.

Goldenberg DL, Egan MS, Cohen AS. Inflammatory synovitis in degenerative joint disease. J Rheumatol. 1982;9(2):204–9.

Lindblad S, Hedfors E. Arthroscopic and immunohistologic characterization of knee joint synovitis in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(10):1081–8.

Revell PA, Mayston V, Lalor P, et al. The synovial membrane in osteoarthritis: a histological study including the characterisation of the cellular infiltrate present in inflammatory osteoarthritis using monoclonal antibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47(4):300–7.

Smith MD, Triantafillou S, Parker A, et al. Synovial membrane inflammation and cytokine production in patients with early osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(2):365–71.

Kawashiri SY, Suzuki T, Nakashima Y, et al. Synovial inflammation assessed by ultrasonography correlates with MRI-proven osteitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(8):1452–6.

Loeser RF, Yammani RR, Carlson CS, et al. Articular chondrocytes express the receptor for advanced glycation end products: potential role in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(8):2376–85.

Krasnokutsky S, Belitskaya-Lévy I, Bencardino J, et al. Quantitative MRI evidence of synovial proliferation is associated with radiographic severity of knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):2983–91.

Amos N, Lauder S, Evans A, et al. Adenoviral gene transfer into osteoarthritis synovial cells using the endogenous inhibitor IkBα reveals that most, but not all, inflammatory and destructive mediators are NFkB dependent. Rheumatology. 2006;45(10):1201–9.

Benito MJ, Veale DJ, FitzGerald O, et al. Synovial tissue inflammation in early and late osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(9):1263–7.

Lisignoli G, Toneguzzi S, Pozzi C, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines and chemokine production and expression by human osteoblasts isolated from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(4):791–9.

Fonseca J, Cortez-Dias N, Francisco A, et al. Inflammatory cell infiltrate and RANKL/OPG expression in rheumatoid synovium: comparison with other inflammatory arthropathies and correlation with outcome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;23(2):185–92.

Kunisch E, Fuhrmann R, Roth A, et al. Macrophage specificity of three anti-CD68 monoclonal antibodies (KP1, EBM11, and PGM1) widely used for immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(7):774–84.

Blom AB, van Lent PL, Libregts S, et al. Crucial role of macrophages in matrix metalloproteinase–mediated cartilage destruction during experimental osteoarthritis: involvement of matrix metalloproteinase 3. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(1):147–57. This paper describes the crucial role of synovial macrophage in early MMP activity and MMP production.

Blom AB, van Lent PL, Holthuysen AE, et al. Synovial lining macrophages mediate osteophyte formation during experimental osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2004;12(8):627–35.

Foxwell B, Browne K, Bondeson J, et al. Efficient adenoviral infection with IkappaB alpha reveals that macrophage tumor necrosis factor alpha production in rheumatoid arthritis is NF-kappaB dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(14):8211–5.

Brennan FM, Chantry D, Jackson A, et al. Inhibitory effect of TNF alpha antibodies on synovial cell interleukin-1 production in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1989;2(8657):244–7.

Bondeson J. Activated synovial macrophages as targets for osteoarthritis drug therapy. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11(5):576–85. A review paper discusses the potential of synovial macrophages and their mediators (pro-inflammatory cytokines) as potential therapeutic targets in OA.

Liu Y-C, Zou X-B, Chai Y-F, et al. Macrophage polarization in inflammatory diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2014;10(5):520.

Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(12):958–69.

Barros MH, Hauck F, Dreyer JH, et al. Macrophage polarisation: an immunohistochemical approach for identifying M1 and M2 macrophages. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11), e80908.

Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, et al. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J Immunol. 2006;177(10):7303–11.

Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, et al. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(12):677–86.

Stein M, Keshav S, Harris N, et al. Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 1992;176(1):287–92.

Ezekowitz RA, Stahl PD. The structure and function of vertebrate mannose lectin-like proteins. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1988;9:121–33.

Ambarus CA, Noordenbos T, de Hair MJ, et al. Intimal lining layer macrophages but not synovial sublining macrophages display an IL-10 polarized-like phenotype in chronic synovitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(2):R74.

Berenbaum F. Signaling transduction: target in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(5):616–22.

Caron JP, Fernandes JC, Martel‐Pelletier J, et al. Chondroprotective effect of intraarticular injections of interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist in experimental osteoarthritis. Suppression of collagenase‐1 expression. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(9):1535–44.

Henderson B, Pettipher ER. Arthritogenic actions of recombinant IL-1 and tumour necrosis factor alpha in the rabbit: evidence for synergistic interactions between cytokines in vivo. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;75(2):306–10.

O’Byrne EM, Blancuzzi V, Wilson DE, et al. Elevated substance P and accelerated cartilage degradation in rabbit knees injected with interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(7):1023–8.

Pettipher ER, Higgs GA, Henderson B. Interleukin 1 induces leukocyte infiltration and cartilage proteoglycan degradation in the synovial joint. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1986;83(22):8749–53.

Thomas DP, King B, Stephens T, et al. In vivo studies of cartilage regeneration after damage induced by catabolin/interleukin-1. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50(2):75–80.

Daghestani HN, Pieper CF, Kraus VB. Soluble macrophage biomarkers indicate inflammatory phenotypes in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(4):956–65.

Krutzik SR, Sieling PA, Modlin RL. The role of toll-like receptors in host defense against microbial infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13(1):104–8.

Akashi S, Ogata H, Kirikae F, et al. Regulatory roles for CD14 and phosphatidylinositol in the signaling via toll-like receptor 4-MD-2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268(1):172–7.

Wright SD, Ramos RA, Tobias PS, et al. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science. 1990;249(4975):1431–3.

Katz JD, Agrawal S, Velasquez M. Getting to the heart of the matter: osteoarthritis takes its place as part of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22(5):512–9.

Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121):860–7.

Prieur X, Rőszer T, Ricote M. Lipotoxicity in macrophages: evidence from diseases associated with the metabolic syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2010;1801(3):327–37.

Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(10):889–96.

Wang XM, Kim HP, Song R, et al. Caveolin-1 confers antiinflammatory effects in murine macrophages via the MKK3/p38 MAPK pathway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34(4):434–42.

Satoh T, Takeuchi O, Vandenbon A, et al. The Jmjd3-Irf4 axis regulates M2 macrophage polarization and host responses against helminth infection. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(10):936–44.

Xu H, Zhu J, Smith S, et al. Notch-RBP-J signaling regulates the transcription factor IRF8 to promote inflammatory macrophage polarization. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(7):642–50.

Kamei N, Tobe K, Suzuki R, et al. Overexpression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in adipose tissues causes macrophage recruitment and insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(36):26602–14.

Weisberg SP, Hunter D, Huber R, et al. CCR2 modulates inflammatory and metabolic effects of high-fat feeding. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(1):115–24.

Amano SU, Cohen JL, Vangala P, et al. Local proliferation of macrophages contributes to obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Cell Metab. 2014;19(1):162–71.

Surmi BK, Hasty AH. The role of chemokines in recruitment of immune cells to the artery wall and adipose tissue. Vasc Pharmacol. 2010;52(1):27–36.

Li P, Bandyopadhyay G, Lagakos WS, et al. LTB4 promotes insulin resistance in obese mice by acting on macrophages, hepatocytes and myocytes. Nature medicine 2015.

Tsao C-H, Shiau M-Y, Chuang P-H, et al. Interleukin-4 regulates lipid metabolism by inhibiting adipogenesis and promoting lipolysis. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(3):385–97.

Kawanishi N, Yano H, Mizokami T, et al. Exercise training attenuates hepatic inflammation, fibrosis and macrophage infiltration during diet induced-obesity in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(6):931–41.

Bradley RL, Jeon JY, Liu F-F, et al. Voluntary exercise improves insulin sensitivity and adipose tissue inflammation in diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol-Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;295(3):E586–94.

Kawanishi N, Mizokami T, Yano H, et al. Exercise attenuates M1 macrophages and CD8+ T cells in the adipose tissue of obese mice. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(9):1684–93.

Qatanani M, Lazar MA. Mechanisms of obesity-associated insulin resistance: many choices on the menu. Genes Dev. 2007;21(12):1443–55.

Vlassara H, Palace MR. Diabetes and advanced glycation endproducts. J Intern Med. 2002;251(2):87–101.

Obrenovich ME, Monnier VM. Apoptotic killing of fibroblasts by matrix-bound advanced glycation endproducts. Sci Ag ing Knowl Environ. 2005;2005(4):pe3.

Jin X, Yao T, Zhou Ze, et al. Advanced glycation end products enhance macrophages polarization into M1 phenotype through activating RAGE/NF-kB pathway. BioMed research international 2015; 2015.

Stannus OP, Jones G, Quinn SJ, et al. The association between leptin, interleukin-6, and hip radiographic osteoarthritis in older people: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(3):R95.

Kohli P, Levy BD. Resolvins and protectins: mediating solutions to inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(4):960–71.

Qu Q, Xuan W, Fan GH. Roles of resolvins in the resolution of acute inflammation. Cell Biol Int. 2015;39(1):3–22.

Levy BD. Resolvins and protectins: natural pharmacophores for resolution biology. Prostaglandins, Leukot Essent Fatty Acids (PLEFA). 2010;82(4):327–32.

Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294(5548):1871–5.

Abdellatif KR, Chowdhury MA, Dong Y, et al. Diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolated and nitrooxyethyl nitric oxide donor ester prodrugs of anti-inflammatory (E)-2-(aryl)-3-(4-methanesulfonylphenyl)acrylic acids: synthesis, cyclooxygenase inhibition, and nitric oxide release studies. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16(6):3302–8.

Samuelsson B. Leukotrienes: mediators of immediate hypersensitivity reactions and inflammation. Science. 1983;220(4597):568–75.

Arita M, Ohira T, Sun Y-P, et al. Resolvin E1 selectively interacts with leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 and ChemR23 to regulate inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;178(6):3912–7.

Miyahara N, Miyahara S, Takeda K, et al. Role of the LTB4/BLT1 pathway in allergen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness inflammation. Allergol Int. 2006;55(2):91–7.

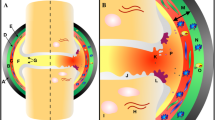

Tian W, Jiang X, Tamosiuniene R, et al. Blocking macrophage leukotriene b4 prevents endothelial injury and reverses pulmonary hypertension. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(200):200ra117. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3006674.

Ahmadzadeh N, Shingu M, Nobunaga M, et al. Relationship between leukotriene B4 and immunological parameters in rheumatoid synovial fluids. Inflammation. 1991;15(6):497–503.

Damon M, Chavis C, Daures J, et al. Increased generation of the arachidonic metabolites LTB4 and 5-HETE by human alveolar macrophages in patients with asthma: effect in vitro of nedocromil sodium. Eur Respir J. 1989;2(3):202–9.

Wittenberg RH, Willburger RE, Kleemeyer KS, et al. In vitro release of prostaglandins and leukotrienes from synovial tissue, cartilage, and bone in degenerative joint diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(10):1444–50.

Xu MX, Tan BC, Zhou W, et al. Resolvin D1, an endogenous lipid mediator for inactivation of inflammation‐related signaling pathways in microglial cells, prevents lipopolysaccharide‐induced inflammatory responses. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2013;19(4):235–43.

Lima‐Garcia J, Dutra R, Da Silva K, et al. The precursor of resolvin D series and aspirin‐triggered resolvin D1 display anti‐hyperalgesic properties in adjuvant‐induced arthritis in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(2):278–93.

Schif‐Zuck S, Gross N, Assi S, et al. Saturated‐efferocytosis generates pro‐resolving CD11blow macrophages: modulation by resolvins and glucocorticoids. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(2):366–79.

Zhang Y, Vasheghani F, Li Y-h, et al. Cartilage-specific deletion of mTOR upregulates autophagy and protects mice from osteoarthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2014: pp. annrheumdis-2013-204599.

Marcheselli VL, Hong S, Lukiw WJ, et al. Novel docosanoids inhibit brain ischemia-reperfusion-mediated leukocyte infiltration and pro-inflammatory gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(44):43807–17.

Marcheselli VL, Mukherjee PK, Arita M, et al. Neuroprotectin D1/protectin D1 stereoselective and specific binding with human retinal pigment epithelial cells and neutrophils. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2010;82(1):27–34.

Serhan CN, Gotlinger K, Hong S, et al. Anti-inflammatory actions of neuroprotectin D1/protectin D1 and its natural stereoisomers: assignments of dihydroxy-containing docosatrienes. J Immunol. 2006;176(3):1848–59.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not describe studies in which experiments were performed on human or animal subjects.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Osteoarthritis

Antonia RuJia Sun and Thor Friis contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, A.R., Friis, T., Sekar, S. et al. Is Synovial Macrophage Activation the Inflammatory Link Between Obesity and Osteoarthritis?. Curr Rheumatol Rep 18, 57 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-016-0605-9

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-016-0605-9