Abstract

Purpose

Down syndrome (DS) is caused by trisomy 21 (Ts21) and results in skeletal deficits including shortened stature, low bone mineral density, and a predisposition to early onset osteoporosis. Ts21 causes significant alterations in skeletal development, morphology of the appendicular skeleton, bone homeostasis, age-related bone loss, and bone strength. However, the genetic or cellular origins of DS skeletal phenotypes remain unclear.

Recent Findings

New studies reveal a sexual dimorphism in characteristics and onset of skeletal deficits that differ between DS and typically developing individuals. Age-related bone loss occurs earlier in the DS as compared to general population.

Summary

Perturbations of DS skeletal quality arise from alterations in cellular and molecular pathways affected by the overexpression of trisomic genes. Sex-specific alterations occur in critical developmental pathways that disrupt bone accrual, remodeling, and homeostasis and are compounded by aging, resulting in increased risks for osteopenia, osteoporosis, and fracture in individuals with DS.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

de Graaf G, Buckley F, Skotko BG. Estimation of the number of people with Down syndrome in the United States. Genet Med. 2017;19(4):439–47. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.127.

de Moraes ME, Tanaka JL, de Moraes LC, Filho EM, de Melo Castilho JC. Skeletal age of individuals with Down Syndrome. Spec Care Dentist. 2008;28(3):101–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-4505.2008.00020.x.

Keeling JW, Hansen BF, Kjaer I. Pattern of malformations in the axial skeleton in human trisomy 21 fetuses. Am J Med Genet. 1997;68(4):466–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19970211)68:4<466::AID-AJMG19>3.0.CO;2-Q.

Barden HS. Growth and development of selected hard tissues in Down syndrome: a review. Hum Biol. 1983;55(3):539–76.

Nyberg DA, Souter VL, El-Bastawissi A, Young S, Luthhardt F, Luthy DA. Isolated sonographic markers for detection of fetal Down syndrome in the second trimester of pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20(10):1053–63. https://doi.org/10.7863/jum.2001.20.10.1053.

Bromley B, Lieberman E, Shipp TD, Benacerraf BR. The genetic sonogram: a method of risk assessment for Down syndrome in the second trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21(10):1087–96 quiz 97-8.

Rarick GL, Rapaport IF, Seefeldt V. Long bone growth in down’s syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112(6):566–71. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1966.02090150110012.

Guihard-Costa AM, Khung S, Delbecque K, Menez F, Delezoide AL. Biometry of face and brain in fetuses with trisomy 21. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(1):33–8.

Baptista F, Varela A, Sardinha LB. Bone mineral mass in males and females with and without Down syndrome. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(4):380–8.

Angelopoulou N, Souftas V, Sakadamis A, Mandroukas K. Bone mineral density in adults with Down's syndrome. Eur Radiol. 1999;9(4):648–51.

Esbensen AJ. Health conditions associated with aging and end of life of adults with Down syndrome. Int Rev Res Ment Retard. 2010;39(C):107–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7750(10)39004-5.

Hawli Y, Nasrallah M, El-Hajj Fuleihan G. Endocrine and musculoskeletal abnormalities in patients with Down syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(6):327–34.

Center J, Beange H, McElduff A. People with mental retardation have an increased prevalence of osteoporosis: a population study. Am J Ment Retard. 1998;103(1):19–28. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(1998)103<0019:PWMRHA>2.0.CO;2.

Garcia-Hoyos M, Riancho JA, Valero C. Bone health in Down syndrome. Med Clin (Barc). 2017;149(2):78–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2017.04.020.

Gonzalez-Aguero A, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Gomez-Cabello A, Casajus JA. Cortical and trabecular bone at the radius and tibia in male and female adolescents with Down syndrome: a peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) study. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(3):1035–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2041-7.

• LaCombe JM, Roper RJ. Skeletal dynamics of Down syndrome: a developing perspective. Bone. 2020;133:115215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2019.115215Bone abnormalities in DS result from changes in bone formation and homeostasis early in development. Adolescents with DS have a high rate of fractures.

Matute-Llorente A, Gonzalez-Aguero A, Gomez-Cabello A, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Casajus JA. Decreased levels of physical activity in adolescents with Down syndrome are related with low bone mineral density: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2013;13:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6823-13-22.

•• Tang JYM, Luo H, Wong GHY, Lau MMY, Joe GM, Tse MA, et al. Bone mineral density from early to middle adulthood in persons with Down syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2019;63(8):936–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12608Individuals with DS exhibited age-related bone loss compared to those without DS, with men with DS exhibiting gradual bone loss since early adulthood, increasing their risk for onset of osteoporosis compared to females with DS. BMD in adults with DS with continued age-related loss in men and rapid loss in women with DS.

Baird PA, Sadovnick AD. Life tables for Down syndrome. Hum Genet. 1989;82(3):291–2.

Bittles AH, Glasson EJ. Clinical, social, and ethical implications of changing life expectancy in Down syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46(4):282–6.

Weijerman ME, de Winter JP. Clinical practice. The care of children with Down syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169(12):1445–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-010-1253-0.

Whooten R, Schmitt J, Schwartz A. Endocrine manifestations of Down syndrome. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2018;25(1):61–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000382.

•• Burke EA, Carroll R, O'Dwyer MO, Walsh JB, McCallion P, McCarron M. Osteoporosis and people with Down syndrome: a preliminary descriptive examination of the intellectual disability supplement to the irish longitudinal study on ageing wave 1 results. Health. 2018;10:1233–49 Individuals with are considered a high risk group for the development of osteopenia and osteoporosis compared to the general population and low screening rates might lead to undiagnosed skeletal disease.

Myrelid A, Gustafsson J, Ollars B, Anneren G. Growth charts for Down’s syndrome from birth to 18 years of age. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87(2):97–103. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.87.2.97.

Zemel BS, Pipan M, Stallings VA, Hall W, Schadt K, Freedman DS, et al. Growth charts for children with down syndrome in the United States. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1204–11. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1652.

Burr DB, Allen MR. Basic and applied bone biology. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2013.

Baxter-Jones AD, Faulkner RA, Forwood MR, Mirwald RL, Bailey DA. Bone mineral accrual from 8 to 30 years of age: an estimation of peak bone mass. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(8):1729–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.412.

Gonzalez-Aguero A, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Moreno LA, Casajus JA. Bone mass in male and female children and adolescents with Down syndrome. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(7):2151–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1443-7.

Burke EA, McCallion P, Carroll R, Walsh JB, McCarron M. An exploration of the bone health of older adults with an intellectual disability in Ireland. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2017;61(2):99–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12273.

van Allen MI, Fung J, Jurenka SB. Health care concerns and guidelines for adults with Down syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89(2):100–10.

Angelopoulou N, Matziari C, Tsimaras V, Sakadamis A, Souftas V, Mandroukas K. Bone mineral density and muscle strength in young men with mental retardation (with and without Down syndrome). Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;66(3):176–80.

•• Costa R, De Miguel R, Garcia C, de Asua DR, Castaneda S, Moldenhauer F, et al. Bone mass assessment in a cohort of adults with Down syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2017;55(5):315–24. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-55.5.315Areal BMD study of a large cohort of individuals with DS found high rate of osteopenia and osteoporosis in the femoral neck and lumbar spine. Young adults with DS have BMD that is similar to postmenopausal women, with males having lower levesl than females with DS.

McKelvey KD, Fowler TW, Akel NS, Kelsay JA, Gaddy D, Wenger GR, et al. Low bone turnover and low bone density in a cohort of adults with Down syndrome. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(4):1333–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-2109-4.

Herault Y, Delabar JM, Fisher EMC, Tybulewicz VLJ, Yu E, Brault V. Rodent models in Down syndrome research: impact and future opportunities. Dis Model Mech. 2017;10(10):1165–86. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.029728.

Gupta M, Dhanasekaran AR, Gardiner KJ. Mouse models of Down syndrome: gene content and consequences. Mamm Genome. 2016;27(11-12):538–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00335-016-9661-8.

Reeves RH, Irving NG, Moran TH, Wohn A, Kitt C, Sisodia SS, et al. A mouse model for Down syndrome exhibits learning and behaviour deficits. Nat Genet. 1995;11(2):177–84.

Blazek JD, Gaddy A, Meyer R, Roper RJ, Li J. Disruption of bone development and homeostasis by trisomy in Ts65Dn Down syndrome mice. Bone. 2011;48(2):275–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2010.09.028.

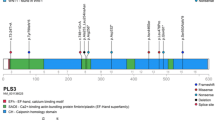

Blazek JD, Abeysekera I, Li J, Roper RJ. Rescue of the abnormal skeletal phenotype in Ts65Dn Down syndrome mice using genetic and therapeutic modulation of trisomic Dyrk1a. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(20):5687–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddv284.

Fowler TW, McKelvey KD, Akel NS, Vander Schilden J, Bacon AW, Bracey JW, et al. Low bone turnover and low BMD in Down syndrome: effect of intermittent PTH treatment. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42967. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042967.

Olson LE, Richtsmeier JT, Leszl J, Reeves RH. A chromosome 21 critical region does not cause specific Down syndrome phenotypes. Science. 2004;306(5696):687–90.

Olson LE, Roper RJ, Sengstaken CL, Peterson EA, Aquino V, Galdzicki Z, et al. Trisomy for the Down syndrome 'critical region' is necessary but not sufficient for brain phenotypes of trisomic mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(7):774–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddm022.

Olson LE, Mohan S. Bone density phenotypes in mice aneuploid for the Down syndrome critical region. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155(10):2436–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.34203.

•• Thomas JR, LaCombe J, Long R, Lana-Elola E, Watson-Scales S, Wallace JM, et al. Interaction of sexual dimorphism and gene dosage imbalance in skeletal deficits associated with Down syndrome. Bone. 2020;136:115367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2020.115367Sexual dimorphism, age, gene dosage and skeletal sites are influenced by three copies of genes homologous to Hsa21 and result in sex-specific and age-related skeletal abnormalities.

Lana-Elola E, Watson-Scales S, Slender A, Gibbins D, Martineau A, Douglas C, et al. Genetic dissection of Down syndrome-associated congenital heart defects using a new mouse mapping panel. eLife. 2016;5. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.11614.

Guijarro M, Valero C, Paule B, Gonzalez-Macias J, Riancho JA. Bone mass in young adults with Down syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2008;52(Pt 3):182–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00992.x.

•• Carfi A, Liperoti R, Fusco D, Giovannini S, Brandi V, Vetrano DL, et al. Bone mineral density in adults with Down syndrome. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(10):2929–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4133-xAdults with DS have lower bone mineral density compared to the general population, and a sharp decline in bone mass with age, men with DS have lower BMAD compared to women with DS.

Garcia-Hoyos M, Garcia-Unzueta MT, de Luis D, Valero C, Riancho JA. Diverging results of areal and volumetric bone mineral density in Down syndrome. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(3):965–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3814-1.

• Garcia Hoyos M, Humbert L, Salmon Z, Riancho JA, Valero C. Analysis of volumetric BMD in people with Down syndrome using DXA-based 3D modeling. Arch Osteoporos. 2019;14(1):98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-019-0645-7Femurs analyzed with DXA-based 3D modeling technique revealed individuals with DS had lower vBMD compared to those without DS and age related bone loss was more pronounced in individuals with DS.

Wu J. Bone mass and density in preadolescent boys with and without Down syndrome. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(11):2847–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2393-7.

•• Costa R, Gullon A, De Miguel R, de Asua DR, Bautista A, Garcia C, et al. Bone mineral density distribution curves in Spanish adults with Down syndrome. J Clin Densitom. 2018;21(4):493–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocd.2018.03.001Individuals with DS reach peak bone mass earlier and have lower bone mineral density compared to the general population and the male gender is at an increased risk for developing low bone mineral density.

Barnhart RC, Connolly B. Aging and Down syndrome: implications for physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2007;87(10):1399–406. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20060334.

Grimwood JS, Kumar A, Bickerstaff DR, Suvarna SK. Histological assessment of vertebral bone in a Down's syndrome adult with osteoporosis. Histopathology. 2000;36(3):279–80.

Kamalakar A, Harris JR, McKelvey KD, Suva LJ. Aneuploidy and skeletal health. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2014;12(3):376–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-014-0221-4.

Blazek JD, Malik AM, Tischbein M, Arbones ML, Moore CS, Roper RJ. Abnormal mineralization of the Ts65Dn Down syndrome mouse appendicular skeleton begins during embryonic development in a Dyrk1a-independent manner. Mech Dev. 2015;136:133–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mod.2014.12.004.

• Williams DK, Parham SG, Schryver E, Akel NS, Shelton RS, Webber J, et al. Sclerostin antibody treatment stimulates bone formation to normalize bone mass in male down syndrome mice. JBMR Plus. 2018;2(1):47–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10025Examines the relationship between bone mineral density and skeletal health in individuals with Down syndrome.

Gonzalez-Aguero A, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Gomez-Cabello A, Ara I, Moreno LA, Casajus JA. A 21-week bone deposition promoting exercise programme increases bone mass in young people with Down syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(6):552–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04262.x.

Matute-Llorente A, Gonzalez-Aguero A, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Sardinha LB, Baptista F, Casajus JA. Physical activity and bone mineral density at the femoral neck subregions in adolescents with Down syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2017;30(10):1075–82. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2017-0024.

Matute-Llorente A, Gonzalez-Aguero A, Gomez-Cabello A, Olmedillas H, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Casajus JA. Effect of whole body vibration training on bone mineral density and bone quality in adolescents with Down syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(10):2449–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3159-1.

Antonarakis SE, Skotko BG, Rafii MS, Strydom A, Pape SE, Bianchi DW, et al. Down syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0143-7.

Stamoulis G, Garieri M, Makrythanasis P, Letourneau A, Guipponi M, Panousis N, et al. Single cell transcriptome in aneuploidies reveals mechanisms of gene dosage imbalance. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4495. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12273-8.

Wiseman FK, Alford KA, Tybulewicz VL, Fisher EM. Down syndrome--recent progress and future prospects. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(R1):R75–83.

Arron JR, Winslow MM, Polleri A, Chang CP, Wu H, Gao X, et al. NFAT dysregulation by increased dosage of DSCR1 and DYRK1A on chromosome 21. Nature. 2006;441(7093):595–600.

Duchon A, Herault Y. DYRK1A, a dosage-sensitive gene involved in neurodevelopmental disorders, is a target for drug development in Down syndrome. Front Behav Neurosci. 2016;10:104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00104.

Altafaj X, Dierssen M, Baamonde C, Marti E, Visa J, Guimera J, et al. Neurodevelopmental delay, motor abnormalities and cognitive deficits in transgenic mice overexpressing Dyrk1A (minibrain), a murine model of Down's syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(18):1915–23.

Branchi I, Bichler Z, Minghetti L, Delabar JM, Malchiodi-Albedi F, Gonzalez MC, et al. Transgenic mouse in vivo library of human Down syndrome critical region 1: association between DYRK1A overexpression, brain development abnormalities, and cell cycle protein alteration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63(5):429–40.

Guedj F, Pereira PL, Najas S, Barallobre MJ, Chabert C, Souchet B, et al. DYRK1A: a master regulatory protein controlling brain growth. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46(1):190–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2012.01.007.

Park J, Song WJ, Chung KC. Function and regulation of Dyrk1A: towards understanding Down syndrome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(20):3235–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-009-0123-2.

Lee Y, Ha J, Kim HJ, Kim YS, Chang EJ, Song WJ, et al. Negative feedback Inhibition of NFATc1 by DYRK1A regulates bone homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(48):33343–51. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.042234.

Stringer M, Goodlett CR, Roper RJ. Targeting trisomic treatments: optimizing Dyrk1a inhibition to improve Down syndrome deficits. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2017;5(5):451–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.334.

Abbassi R, Johns TG, Kassiou M, Munoz L. DYRK1A in neurodegeneration and cancer: Molecular basis and clinical implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;151:87–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.03.004.

Hammerle B, Ulin E, Guimera J, Becker W, Guillemot F, Tejedor FJ. Transient expression of Mnb/Dyrk1a couples cell cycle exit and differentiation of neuronal precursors by inducing p27KIP1 expression and suppressing NOTCH signaling. Development. 2011;138(12):2543–54. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.066167.

He Y, Staser K, Rhodes SD, Liu Y, Wu X, Park SJ, et al. Erk1 positively regulates osteoclast differentiation and bone resorptive activity. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24780. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024780.

Neal JW, Clipstone NA. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibits the DNA binding activity of NFATc. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(5):3666–73. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M004888200.

Sato K, Suematsu A, Nakashima T, Takemoto-Kimura S, Aoki K, Morishita Y, et al. Regulation of osteoclast differentiation and function by the CaMK-CREB pathway. Nat Med. 2006;12(12):1410–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1515.

Soppa U, Schumacher J, Florencio Ortiz V, Pasqualon T, Tejedor FJ, Becker W. The Down syndrome-related protein kinase DYRK1A phosphorylates p27(Kip1) and Cyclin D1 and induces cell cycle exit and neuronal differentiation. Cell Cycle. 2014;13(13):2084–100. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.29104.

Souchet B, Guedj F, Penke-Verdier Z, Daubigney F, Duchon A, Herault Y, et al. Pharmacological correction of excitation/inhibition imbalance in Down syndrome mouse models. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:267. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00267.

Valenti D, de Bari L, de Rasmo D, Signorile A, Henrion-Caude A, Contestabile A, et al. The polyphenols resveratrol and epigallocatechin-3-gallate restore the severe impairment of mitochondria in hippocampal progenitor cells from a Down syndrome mouse model. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862(6):1093–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.03.003.

Deshmukh V, O'Green AL, Bossard C, Seo T, Lamangan L, Ibanez M, et al. Modulation of the Wnt pathway through inhibition of CLK2 and DYRK1A by lorecivivint as a novel, potentially disease-modifying approach for knee osteoarthritis treatment. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(9):1347–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.05.006.

Granno S, Nixon-Abell J, Berwick DC, Tosh J, Heaton G, Almudimeegh S, et al. Downregulated Wnt/beta-catenin signalling in the Down syndrome hippocampus. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7322. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43820-4.

Zainabadi K, Liu CJ, Caldwell ALM, Guarente L. SIRT1 is a positive regulator of in vivo bone mass and a therapeutic target for osteoporosis. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0185236. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185236.

Funding

Work on this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15HD090603. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Genetics

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, J.R., Roper, R.J. Current Analysis of Skeletal Phenotypes in Down Syndrome. Curr Osteoporos Rep 19, 338–346 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-021-00674-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-021-00674-y