Abstract

Purpose of Review

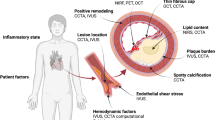

Imaging of adverse coronary plaque features by coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) has advanced greatly and at a fast pace. We aim to describe the evolution, present and future in plaque analysis, and its value in comparison to plaque burden.

Recent Findings

Recently, it has been demonstrated that in addition to plaque burden, quantitative and qualitative assessment of coronary plaque by CCTA can improve the prediction of future major adverse cardiovascular events in diverse coronary artery disease scenarios. The detection of high-risk non-obstructive coronary plaque can lead to higher use of preventive medical therapies such as statins and aspirin, help identify culprit plaque, and differentiate between myocardial infarction types. Even more, over traditional plaque burden, plaque analysis including pericoronary inflammation can potentially be useful tools for tracking disease progression and response to medical therapy.

Summary

The identification of the higher risk phenotypes with plaque burden, plaque characteristics, or ideally both can allow the allocation of targeted therapies and potentially monitor response. Further observational data are now required to investigate these key issues in diverse populations, followed by rigorous randomized controlled trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Gulati M, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;144(22):e368–454. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029.

Williams MC, Earls JP, Hecht H. Quantitative assessment of atherosclerotic plaque, recent progress and current limitations. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2022;16(2):124–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCCT.2021.07.001. Very comprehensive review of the latest available solutions for CCTA advanced plaque analysis and their most common pitfalls.

van Veelen A, van der Sangen NMR, Henriques JPS, Claessen BEPM. Identification and treatment of the vulnerable coronary plaque. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2022;23(1). https://doi.org/10.31083/J.RCM2301039.

Finn AV, Nakano M, Narula J, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Concept of vulnerable/unstable plaque. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(7):1282–92. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179739.

Gaba P, Gersh BJ, Muller J, Narula J, Stone GW. Evolving concepts of the vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque and the vulnerable patient: implications for patient care and future research. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022; Sep 23. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41569-022-00769-8.

Narula J, et al. SCCT 2021 Expert Consensus Document on Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2021;15(3):192–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCCT.2020.11.001.

Cury RC, et al. CAD-RADSTM 2.0 - 2022 Coronary Artery Disease - Reporting and Data System An Expert Consensus Document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the North America Society of Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2022;16(6):536–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcct.2022.07.002.

Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the unstable plaque. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2002;44(5):349–56. https://doi.org/10.1053/PCAD.2002.122475.

Motoyama S, et al. Computed tomographic angiography characteristics of atherosclerotic plaques subsequently resulting in acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1):49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2009.02.068.

Puchner SB, et al. High-risk plaque detected on coronary CT angiography predicts acute coronary syndromes independent of significant stenosis in acute chest pain: results from the ROMICAT-II trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(7):684–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.039.

Shaw LJ et al. Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography/North American Society of Cardiovascular Imaging - Expert Consensus Document on Coronary CT Imaging of Atherosclerotic Plaque. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2021;15(2):93–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCCT.2020.11.002. Expert consensus in how to optimize the imaging of coronary atherosclerosis by CTCA and what features should be stated in the report.

van Veelen A, van der Sangen NMR, Delewi R, Beijk MAM, Henriques JPS, Claessen BEPM. Detection of vulnerable coronary plaques using invasive and non-invasive imaging modalities. J Clin Med. 2022;11(5):1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/JCM11051361.

Achenbach S. Imaging the vulnerable plaque on coronary CTA. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(6):1418–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2019.11.006.

Antonopoulos AS, Angelopoulos A, Tsioufis K, Antoniades C, Tousoulis D. Cardiovascular risk stratification by coronary computed tomography angiography imaging: current state-of-the-art. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29(4):608–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURJPC/ZWAB067.

Seifarth H, et al. Histopathological correlates of the napkin-ring sign plaque in coronary CT angiography. Atherosclerosis. 2012;224(1):90–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATHEROSCLEROSIS.2012.06.021.

Hoffmann U, et al. Noninvasive assessment of plaque morphology and composition in culprit and stable lesions in acute coronary syndrome and stable lesions in stable angina by multidetector computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(8):1655–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2006.01.041.

Motoyama S, et al. Multislice computed tomographic characteristics of coronary lesions in acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(4):319–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2007.03.044.

Kitagawa T, et al. Characterization of noncalcified coronary plaques and identification of culprit lesions in patients with acute coronary syndrome by 64-slice computed tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(2):153–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2008.09.015.

Pflederer T, et al. Characterization of culprit lesions in acute coronary syndromes using coronary dual-source CT angiography. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211(2):437–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATHEROSCLEROSIS.2010.02.001.

Kim SY, et al. The culprit lesion score on multi-detector computed tomography can detect vulnerable coronary artery plaque. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;26(Suppl 2):245–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10554-010-9712-2.

Ferencik M, et al. A computed tomography-based coronary lesion score to predict acute coronary syndrome among patients with acute chest pain and significant coronary stenosis on coronary computed tomographic angiogram. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(2):183–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJCARD.2012.02.066.

Otsuka K, et al. Napkin-ring sign on coronary CT angiography for the prediction of acute coronary syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(4):448–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2012.09.016.

Motoyama S, et al. Plaque characterization by coronary computed tomography angiography and the likelihood of acute coronary events in mid-term follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(4):337–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2015.05.069.

Chang HJ, et al. Coronary atherosclerotic precursors of acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(22):2511–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2018.02.079.

Williams MC, et al. Coronary artery plaque characteristics associated with adverse outcomes in the SCOT-HEART study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(3):291–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2018.10.066.

Lu G, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography assessment of high-risk plaques in predicting acute coronary syndrome. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:743538. https://doi.org/10.3389/FCVM.2021.743538.

Maurovich-Horvat P, Ferencik M, Voros S, Merkely B, Hoffmann U. Comprehensive plaque assessment by coronary CT angiography. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(7):390–402. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2014.60.

Ferencik M, et al. Use of high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaque detection for risk stratification of patients with stable chest pain: a secondary analysis of the PROMISE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(2):144–52. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2017.4973.

Chang HJ, et al. Coronary atherosclerotic precursors of acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(22):2511–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2018.02.079.

Bing R, Loganath K, Adamson P, Newby D, Moss A. Non-invasive imaging of high-risk coronary plaque: the role of computed tomography and positron emission tomography. Br J Radiol. 2020;93(1113):20190740. https://doi.org/10.1259/BJR.20190740.

Razavi AC, et al. Evolving role of calcium density in coronary artery calcium scoring and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(9):1648–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2022.02.026.

Rozanski A, Berman DS. The synergistic use of coronary artery calcium imaging and noninvasive myocardial perfusion imaging for detecting subclinical atherosclerosis and myocardial ischemia. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20(7):59. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11886-018-1001-Z.

Fathala A, Aboulkheir M, Bukhari S, Shoukri MM, Abouzied MM. Benefits of adding coronary calcium score scan to stress myocardial perfusion positron emission tomography imaging. World J Nucl Med. 2019;18(2):149–53. https://doi.org/10.4103/WJNM.WJNM_34_18.

Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15(4):827–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-T.

Ayoub C, et al. Prognostic value of segment involvement score compared to other measures of coronary atherosclerosis by computed tomography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2017;11(4):258–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCCT.2017.05.001.

Leaman DM, Brower RW, Meester GT, Serruys P, van den Brand M. Coronary artery atherosclerosis: severity of the disease, severity of angina pectoris and compromised left ventricular function. Circulation. 1981;63(2):285–92. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.63.2.285.

de Araújo Gonçalves P, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography-adapted Leaman score as a tool to noninvasively quantify total coronary atherosclerotic burden. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;29(7):1575–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10554-013-0232-8.

Min JK, et al. Prognostic value of multidetector coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardio.l. 2007;50(12):1161–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2007.03.067.

Miller JM, et al. Diagnostic performance of coronary angiography by 64-row CT. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(22):2324–36. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMOA0806576.

Graham MM, et al. Validation of three myocardial jeopardy scores in a population-based cardiac catheterization cohort. Am Heart J. 2001;142(2):254–62. https://doi.org/10.1067/MHJ.2001.116481.

Ko BS, et al. The ASLA Score: a CT angiographic index to predict functionally significant coronary stenoses in lesions with intermediate severity-diagnostic accuracy. Radiology. 2015;276(1):91–101. https://doi.org/10.1148/RADIOL.15141231.

Min JK, et al. Rationale and design of the CONFIRM (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes: an InteRnational Multicenter) Registry. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2011;5(2):84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCCT.2011.01.007.

Farooq V, et al. Anatomical and clinical characteristics to guide decision making between coronary artery bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention for individual patients: development and validation of SYNTAX score II. Lancet. 2013;381(9867):639–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60108-7.

Lin A, et al. Deep learning-enabled coronary CT angiography for plaque and stenosis quantification and cardiac risk prediction: an international multicentre study. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4(4):e256–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00022-X.

Abbara S, et al. SCCT guidelines for the performance and acquisition of coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee: endorsed by the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10(6):435–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCCT.2016.10.002.

Szilveszter B, Kolossváry M, Pontone G, Williams MC, Dweck MR, Maurovich-Horvat P. How to quantify coronary atherosclerotic plaque using computed tomography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23(12):1573–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/EHJCI/JEAC192.

Ferencik M, et al. Computed tomography-based high-risk coronary plaque score to predict acute coronary syndrome among patients with acute chest pain--results from the ROMICAT II trial. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2015;9(6):538–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCCT.2015.07.003.

Nadjiri J, et al. Incremental prognostic value of quantitative plaque assessment in coronary CT angiography during 5 years of follow up. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10(2):97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCCT.2016.01.007.

de Knegt MC, et al. Relationship between patient presentation and morphology of coronary atherosclerosis by quantitative multidetector computed tomography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20(11):1221–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/EHJCI/JEY146.

Williams MC, et al. Low-attenuation noncalcified plaque on coronary computed tomography angiography predicts myocardial infarction: results from the multicenter SCOT-HEART trial (Scottish Computed Tomography of the HEART). Circulation. 2020;141(18):1452–62. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044720.

Schuhbaeck A, et al. Interscan reproducibility of quantitative coronary plaque volume and composition from CT coronary angiography using an automated method. Eur Radiol. 2014;24(9):2300–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00330-014-3253-3.

Cheng VY, et al. Reproducibility of coronary artery plaque volume and composition quantification by 64-detector row coronary computed tomographic angiography: an intraobserver, interobserver, and interscan variability study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2009;3(5):312–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCCT.2009.07.001.

Meah MN, et al. Plaque burden and 1-year outcomes in acute chest pain: results from the multicenter RAPID-CTCA trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(11):1916–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2022.04.024.

Meah MN, et al. Distinguishing type 1 from type 2 myocardial infarction by using CT coronary angiography. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2022;4(5). https://doi.org/10.1148/RYCT.220081. Study showing the ability of CCTA to differentiate between type I and type II MI using advanced quantitative plaque features. Type I MI is associated with higher low-attenuation coronary plaque burden.

Ferraro RA, et al. Non-obstructive high-risk plaques increase the risk of future culprit lesions comparable to obstructive plaques without high-risk features: the ICONIC study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21(9):973–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/EHJCI/JEAA048.

Conte E, et al. Age- and sex-related features of atherosclerosis from coronary computed tomography angiography in patients prior to acute coronary syndrome: results from the ICONIC study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;22(1):24–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/EHJCI/JEAA210.

Han D, et al. Association of plaque location and vessel geometry determined by coronary computed tomographic angiography with future acute coronary syndrome-causing culprit lesions. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(3):309–19. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2021.5705.

Stuijfzand WJ, et al. Stress myocardial perfusion imaging vs coronary computed tomographic angiography for diagnosis of invasive vessel-specific coronary physiology: predictive modeling results from the Computed Tomographic Evaluation of Atherosclerotic Determinants of Myocardial Ischemia (CREDENCE) Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(12):1338–48. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2020.3409.

Ahmadi A, et al. Lesion-specific and vessel-related determinants of fractional flow reserve beyond coronary artery stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(4):521–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2017.11.020.

Gu H, et al. Prognostic value of coronary atherosclerosis progression evaluated by coronary CT angiography in patients with stable angina. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(3):1066–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00330-017-5073-8.

Lee SE, et al. Differences in progression to obstructive lesions per high-risk plaque features and plaque volumes with CCTA. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(6):1409–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2019.09.011.

Lee SE, et al. Differential association between the progression of coronary artery calcium score and coronary plaque volume progression according to statins: the Progression of AtheRosclerotic PlAque DetermIned by Computed TomoGraphic Angiography Imaging (PARADIGM) study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20(11):1307–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/EHJCI/JEZ022.

Andelius L, Mortensen MB, Nørgaard BL, Abdulla J. Impact of statin therapy on coronary plaque burden and composition assessed by coronary computed tomographic angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19(8):850–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/EHJCI/JEY012.

Kaiser Y, et al. Association of lipoprotein(a) with atherosclerotic plaque progression. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(3):223–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2021.10.044.

Cau R, et al. Artificial intelligence in computed tomography plaque characterization: a review. Eur J Radiol. 2021;140:109767. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJRAD.2021.109767.

Hong Y, et al. Deep learning-based stenosis quantification from coronary CT angiography. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 2019;10949:88. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2512168.

Matsumoto H, et al. Improved evaluation of lipid-rich plaque at coronary CT angiography: head-to-head comparison with intravascular US. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2019;1(5):e190069. https://doi.org/10.1148/RYCT.2019190069.

von Knebel Doeberitz PL, et al. Coronary CT angiography-derived plaque quantification with artificial intelligence CT fractional flow reserve for the identification of lesion-specific ischemia. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(5):2378–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00330-018-5834-Z.

Dey D, et al. Integrated prediction of lesion-specific ischaemia from quantitative coronary CT angiography using machine learning: a multicentre study. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(6):2655–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00330-017-5223-Z.

Lin A, et al. Machine learning from quantitative coronary computed tomography angiography predicts fractional flow reserve-defined ischemia and impaired myocardial blood flow. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(10):e014369. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.122.014369.

Tzolos E, et al. Pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation, low-attenuation plaque burden, and 5-year risk of myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(6):1078–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2022.02.004.

Oikonomou EK, et al. Non-invasive detection of coronary inflammation using computed tomography and prediction of residual cardiovascular risk (the CRISP CT study): a post-hoc analysis of prospective outcome data. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):929–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31114-0.

Sagris M, et al. Pericoronary fat attenuation index-a new imaging biomarker and its diagnostic and prognostic utility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23(12):e526–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/EHJCI/JEAC174.

Joshi NV, et al. 18F-fluoride positron emission tomography for identification of ruptured and high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques: a prospective clinical trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9918):705–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61754-7.

Kwiecinski J, Slomka PJ, Dweck MR, Newby DE, Berman DS. Vulnerable plaque imaging using 18F-sodium fluoride positron emission tomography. Br J Radiol. 2020;93(1113):20190797. https://doi.org/10.1259/BJR.20190797.

Kwiecinski J, et al. Predictors of 18F-sodium fluoride uptake in patients with stable coronary artery disease and adverse plaque features on computed tomography angiography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21(1):58–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/EHJCI/JEZ152.

Kwiecinski J, et al. Peri-coronary adipose tissue density is associated with 18F-sodium fluoride coronary uptake in stable patients with high-risk plaques. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(10):2000–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCMG.2018.11.032.

Kwiecinski J, et al. Coronary 18F-sodium fluoride uptake predicts outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(24):3061–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2020.04.046.

Pasterkamp G, den Ruijter HM, Libby P. Temporal shifts in clinical presentation and underlying mechanisms of atherosclerotic disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(1):21–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/NRCARDIO.2016.166.

Dweck MR, et al. Contemporary rationale for non-invasive imaging of adverse coronary plaque features to identify the vulnerable patient: a Position Paper from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Atherosclerosis and Vascular Biology and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21(11):1177–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/EHJCI/JEAA201.

Peters SAE, den Ruijter HM, Bots ML, Moons KGM. Improvements in risk stratification for the occurrence of cardiovascular disease by imaging subclinical atherosclerosis: a systematic review. Heart. 2012;98(3):177–84. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300747.

Newby DE, et al. Coronary CT angiography and 5-year risk of myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(10):924–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1805971.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

S. V. has received research support from the Department of Veterans Affairs, NIH, Tahir, and Jooma Family and Honorarium from American College of Cardiology (Associate Editor for Innovations, acc.org). L. S. has received consulting honorarium from Amgen and Phillips and Grant support from Amgen. D. S. B. and D. D. have received software royalties from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. D. D. was supported by grants from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (1R01HL133616 and 1R01HL148787-01A1). MB has received Grants: NIH, FDA, AHA, Amgen, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Advisory Board: Amgen, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Roche, 89Bio, Kaleido, Inozyme, Agepha, Consulting: Emocha health, Kowa. MJB has received Grants: NIH, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Speakers Bureau – Esperion, Amgen. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lorenzatti, D., Piña, P., Csecs, I. et al. Does Coronary Plaque Morphology Matter Beyond Plaque Burden?. Curr Atheroscler Rep 25, 167–180 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-023-01088-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-023-01088-0