Abstract

We conduct a comprehensive analysis of health determinants at the individual and workplace levels. Using a new individual-level German data set, we investigate the influence of these determinants on health, including collegiality, personality traits as measured by the Big Five, commitment to the company and job characteristics, while controlling for a set of standard sociodemographic and employment variables. We are interested in which determinants are important and which are less influential, whether interaction effects should be taken into account and whether the results depend on the modeling and estimation method used. Among the Big Five factors, conscientiousness, agreeableness and emotional stability are positively correlated with good overall health. The influence of job characteristics such as having substantial decision-making authority, not having physically demanding tasks, having pleasant environmental conditions, facing minimal time pressure and not being required to multitask are also positive. If employees frequently receive help when needed from their colleagues and do not feel unfairly criticized by others in the firm, they usually have fewer health problems. Each Big Five item influences mental health, whereas no statistical significance could be found for these items’ relationships with the number of days workers were absent due to sickness, except for neuroticism. These results are, for the most part, robust to different modeling and estimation methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

According to data from the World Bank, the World Health Organization (WHO) and various national sources, mental disorders impose an enormous disease burden on societies throughout the world. This development has fueled interest in research geared towards understanding the determinants of different aspects of health. A wide range of health determinants have been discussed from a theoretical perspective and empirically analyzed. Economic and sociological studies focus only on sociodemographic and employment factors, such as gender, age, education, working hours and income. Personal attitudes and detailed job characteristics are often neglected but are important determinants of health status. This paper is related to that literature but conducts a more comprehensive analysis to prevent omitted variables from biasing the investigation into the role of different factors influences on individual health.

Personality traits, especially those that can be summarized by the Big Five items, develop early in life due to a mixture of genetics and environmental conditions. These personality traits are persistent, determine an individual’s behavior concerning economic decisions and have substantial effects in important areas of life. A priori, the direction of these effects is not always evident and varies across personality trait types. For example, we can expect that under unfavorable conditions, emotional stability moderates negative effects on health. A positively thinking person is less concerned about critical situations. She believes that she can resolve the current issue or that the problem will resolve itself; in this way, her mental health is not impaired. Considerate people also have fewer mental health problems resulting from permanent disputes with colleagues. Physical health may also depend on one’s personality; for example, thorough workers more frequently avoid accidents at work than others do.

The working environment is also important for health. In this context, different dimensions must be distinguished: engaging in physically demanding work, working in unpleasant environmental conditions, having the authority to make decisions, being independent from coworkers and colleagues, facing time pressure and being committed to the company. The most obvious influence on health is that of the first feature. Improvements and the permanent removal of problems related to physically demanding work tend to improve the health of the population. While less educated and lower-wage workers in the manufacturing industry were affected by these problems in the past, recently, mental stress and disorders have increased for highly skilled workers with higher wages. We still know little about the importance of physical and psychological health problems arising from our complex working life.

The joint consideration of personality traits and working conditions as determinants of health is relevant for employers and employees. More detailed knowledge may be helpful for social partners to improve the health status of the workforce. On the one hand, using this information, management can employ workers with specific personality profiles in specific workplaces combined with an appropriate pattern of duties. On the other hand, if improved health follows, increased productivity via higher satisfaction, fewer absences and later retirement may be the consequence. Workers with a specific personality should pay attention to these factors and should base their job choice not only on income but also on job characteristics; for example, neurotic and extroverted workers differ in their health effects, as well as in their performance of the same activities.

In this paper, using a new individual-level German data set, we empirically investigate the influence of personality traits and working conditions on health. We go beyond the existing literature and are able to present interesting new results. First, we incorporate a wide range of personality traits, skills, employment properties and job characteristics as determinants. No other data sets concurrently contain information on working conditions, job commitment and collegiality in combination with personality traits. Second, the estimates show that some features are strongly linked to poor health and that some seem irrelevant. Third, we reveal the importance of interaction effects between different job conditions and between personal characteristics and job features on health. Fourth, these results are robust to alternative models and estimation methods.

2 Theoretical and empirical results in the related literature and the steps in our investigation

The literature presents effects on health from different perspectives. Health determinants such as nutrition, sleep, alcohol use, smoking, drug use, stress and body mass index are channels that are mainly analyzed in the medicine and biology literatures but are also of economic interest (Frankenberg and Thomas 2017; Giuntella and Mazzonna 2016; Bacolod et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2017; Papageorge et al. 2016; Cawley et al. 2017; Hübler 2017). Other important socioeconomic health determinants are parental background, education, employment, wages and job satisfaction (Case and Paxson 2002; Barcellos et al. 2018; Gonsalves and Martins 2018; Fernandez-Val et al. 2013; Bachelet et al. 2015) as well as available strategies for coping with stress (Antonovsky 1979).

Applying insights from psychological research, e.g., targeting negative cognition and developing positive coping strategies, to an economic setting, Wehner et al. (2016) use British longitudinal data to show that low emotional stability is typically negatively related to socioeconomic outcomes, while conscientiousness predicts desirable outcomes. However, the possible mechanisms behind these relations are investigated far less often. The authors address this research gap by analyzing the relation between low emotional stability and poor mental health, as well as the possible mediating effect of conscientiousness, both theoretically and empirically. They show in their empirical analysis that low emotional stability during adolescence predicts poor mental health in adolescence and adulthood and that the relationship remains relatively stable over time. The authors find also that increased conscientiousness mitigates the negative relation between low emotional stability and mental health. In particular, their results suggest that both less emotionally stable and less conscientious individuals are more likely to experience poor mental health due to reduced problem-solving abilities.

From another perspective, Savelyev and Tan (2019) incorporate personality traits into their analyses. In contrast to previous studies, their strategy, which accounts for a comprehensive set of skills, allows them to find that among high-IQ subjects, education is linked to better health-related outcomes. The authors include lifestyle variables such as marriage, divorce and membership in organizations. They find significant linkages between conscientiousness, openness, extraversion, and neuroticism on the one hand and various health-related outcomes on the other hand across the life cycle. They find that health improves when an extreme lack of conscientiousness or emotional stability is addressed. However, the relationships among agreeableness, extraversion, and health-related outcomes are mixed. Openness exhibits an adverse association with health. These mixed results for health-related outcomes lead the authors to doubt that agreeableness, extraversion and openness are potentially valuable health policy targets.

Working conditions vary substantially across workers, play a significant role in job choice and are central components of the compensation received by workers. Preferences vary by demographic group and throughout the wage distribution. Accounting for differences in preferences for working conditions often exacerbates the estimated wage differentials by race, age, and education (Maestas et al. 2018). These results may also be important for effects on health (Fletcher et al. 2011).

The negative health effects of air pollution, noise and heat are widely discussed (e.g., Kampa and Castanas 2008; Stansfield and Crombie 2011; Seltenrich 2015). Case studies and descriptive analyses of their effects on specific diseases are prevalent.

Unfavorable working conditions are determinants of burnout (e.g., Maslach et al. 2001). According to Demerouti et al. (2001), it is reasonable to divide working conditions into factors that emphasize job demands and factors that buffer adverse influences, which are called job resources. An employee facing deadline pressure, a high workload, and frequent interruptions faces high job demands. This does not automatically lead to detrimental health consequences if the employee can use help from colleagues and has leeway in decision making, e.g., regarding the timing of different tasks, her breaks, and her working hours. When demands increase or resources decrease, the resulting imbalance favors the development of work-related mental health problems. In this model, education opens up access to different jobs with different working environments. Educated employees, for example, have more decision-making autonomy (job resource) but also bear more responsibility (job demand). Bakker et al. (2010) conduct a large-scale study to assess both the empirical relevance of the job demand model and to account for the individual resources available. Rydstedt et al. (2007) as well as Häusser et al. (2010) review other studies with that focus.

From a theoretical view, the relationship between working conditions and health is discussed by Karasek (1979), who focused on job demands, decision-making latitude, and mental strain. Extensions and critical analyses determine the further development of the theoretical model (de Jonge and Kompier 1997; de Bruin and Taylor 2006; Fila et al. 2017). The interaction between job demands and decision-making latitude is the central topic. The combination of a low degree of decision-making latitude and heavy job demands is associated with mental strain. The major implication of this study is that redesigning work processes to allow for increases in decision-making latitude for a broad range of workers could reduce mental strain without affecting the job demands that may plausibly be associated with organizational output levels. Occupational health research has stressed the importance of unhealthy working conditions as well as the effects of physical and mental workloads on absences from work due to illness (Beemsterboer et al. 2009; Prümer and Schnabel 2019).

Refinements of this theoretical approach are based on the job demand-control-support model (Johnson and Hall 1988). This model predicts that the highest level of job strain is experienced in environments characterized by high job demands and low job control. However, this model differs in its hypotheses: The strain hypothesis predicts that job demand and job control have additive effects, whereas the buffer hypothesis predicts that job demand and job control have a multiplicative effect and that high job control can ameliorate the negative effects of high job demand.

This model has also been widely criticized. Kain and Jex (2010) suggest that further research should examine different conceptualizations of job demand and measures of individual differences. Recommendations are suggested, such as including different combinations of demand, control and support; operationalizing these dimensions in several different ways in each study to increase the findings on interactive effects; and designing industry- or role-specific measures of these dimensions to improve consistency.

Working conditions are rarely taken into account when health is the focus of empirical analyses. The first branch of the literature in this context is from the field of ergonomics (Westgaard and Winkel 1997). Firms aim to improve workspaces and environments to minimize the risk of injury and to avoid serious harm to health. The second branch is on emotional strain. Pikos (2017) investigates the relationship between work-related mental health problems and multitasking, i.e., the number of tasks performed at work. She finds evidence for a causal effect of multitasking on emotional strain, emotional exhaustion and burnout. The third branch of the literature is on the influence of physically demanding work and unpleasant environmental conditions on health. In a review article, Coenen et al. (2018) show that men with high levels of occupational physical activity had an increased risk of early mortality compared with those engaging in low levels of occupational physical activity. No such association was observed among women, for whom a tendency towards an inverse association was found instead. This research seems to be of special relevance in the context of digitalization (Misra and Stokols 2012; Reinecke et al. 2017).

Kelly (2008) discusses the relationship between job commitment and health. The higher the level of commitment, the more likely the individual will adopt long-term behavioral changes. Since none of these aspects are analyzed in a comprehensive manner, their relative importance is unclear, as is the answer to the question of whether they interact.

This short literature review reveals that many health determinants, such as health behaviors and the Big Five factors, as well as working conditions, job demands and job resources, seem to be of relevance depending on the socioeconomic variables considered. However, due to data limitations, the studies reviewed do not consider the effect of these factors in a wider context. Thus, they neglect the problem of biased estimates due to the omission of relevant variables. Therefore, we conduct a comprehensive analysis to investigate the influence of these determinants.

First, we start with separate analyses of the socioeconomic variables (employment status, occupation groups, work time, training and wages), personal characteristics (age, gender, education and Big Five factors) and working conditions. Our hypothesis is that only some of the variables considered have clear effects and that these variables will exert different influences on different measures of health.

Second, we estimate combined regression models to compare the stability of the results obtained with the stability of those from regressions with determinants belonging to the same group of variables. We expect that the Big Five factors are important for mental health and that socioeconomic variables are relevant for overall health status and objective health measures.

Third, following the arguments provided by the job demands/resources model, e.g., the effect of unfavorable working conditions, the analysis is differentiated with respect to the types of occupational activities, levels of commitment to the firm, and the degree of collegiality, which is required in order to clarify which context has an influence on health. The effects of particular work characteristics on health could be stronger or weaker in conjunction with other features. Two or more driving forces could interact.

Fourth, an endogenous linkage exists between income, job characteristics and collegiality on the one hand and health on the other hand. Disregarding this endogeneity leads to biased estimates of effects on health.

Fifth, the general relationship among personality, work characteristics and health holds for subgroups such as regions and industries, as well as those defined by firm characteristics, workforce structures and age groups.

3 Data and descriptive statistics

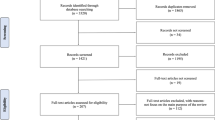

Our data set is the Linked Personnel Panel (LPP—Broszeit and Wolter 2015; Broszeit et al. 2016). This new data set is representative of private sector establishments with at least 50 employees in the manufacturing and services industries and provides information on the employee and employer level. We focus on the former group. The survey was started in 2013 (N = 7508). Information from the second wave in 2015 (N = 7282) and from the third wave in 2017 (N = 6779) is also available. Not all information is provided in all three waves. The employee level of the LPP includes demographics, health status, qualifications, employment, and personal and job characteristics.

Health is idiosyncratic, making its measurement difficult (Baker et al. 2004). The first health variable used contains elements of both physical and mental health. It is a worker’s evaluation on a five-level scale (HEALTH: 1-very good, 2-good, 3-satisfactory, 4-not so good, 5-bad). Our data set also offers some information on mental health based on five statements:

-

I am happy and in a good mood.

-

I feel light and relaxed.

-

I am active and have a lot of energy.

-

I feel fresh and relaxed when I wake up.

-

Many things and activities in which I am personally interested characterize my everyday life.

The respondents were asked whether they agreed with these statements. The answers were measured on a rating scale (1-at any time, …, 6-never). We summarize the outcome of all five items and call this variable MENTAL health (psychological well-being). The scale ranges between 5 and 30. The lower the value is, the better the overall mental health.

A third health indicator in our survey is the number of working days in which the employees were absent due to illness (ABSENT). This is an objective health measure but does not illustrate the complete spectrum of health outcomes. Following Prümer and Schnabel (2019), we do not exclude those employees from our estimation sample who record very long absences from work because such a restriction does not substantially affect our results. Correlations between HEALTH, MENTAL and ABSENT are presented in Table 1.

In contrast to other data sets, information about job characteristics, job commitment, collegiality and personality traits as measured by the Big Five are available in the LPP. Nine items on job characteristics are available; however, we use only the seven that are collected in all three waves (JC1–JC7; see Tables 2 and 3). Six commitment items are distinguished (COM1–COM6; Tables 2 and 3). For the job characteristic and the commitment items, respondents evaluate whether each statement applies to them using the range of 1 to 5. Low values for items COM4, COM5 and COM6 indicate no commitment, in contrast to low values for items COM1–COM3, which indicate high commitment. Collegiality is measured by three questions (COL 1–COL 3; Tables 2 and 3). Respondents have five answer options: always, often, sometimes, rarely, never/nearly never. We transform this categorical attribute into a scale from 1 to 5, where low values for COL1 and COL2 indicate a high degree of collegiality. Low values for COL3 indicate low or no collegiality.

Using a short scale for assessing the Big Five dimensions of personality developed by the German Socio-Economic Panel Group and based on the Big Five inventory of John et al. (1991), respondents answer questions relating to 16 areas of personality. Based on five categories (1: fully applies, 2: largely applies, 3: undecided, 4: does not apply very well, 5: does not apply at all), the respondents give their subjective assessment of their individual personality. Again, the categorical variable is transformed into the scale 1, …, 5. The Big Five factors, namely, openness (OPEN), extraversion (EXTRA), conscientiousness (CONSC), agreeableness (AGREE) and neuroticism (NEURO), are determined based on the sum of the scores generated from answers to three questions. This means that the minimum score for each factor is equal to three and the maximum score is equal to 15. Openness characterizes people who are original, have new ideas, have artistic and aesthetic experiences and are imaginative. Extraversion describes people who are communicative, talkative, outgoing, sociable and not reserved. Typical traits for people with conscientiousness include being thorough workers, not being lazy and being effective and efficient in completing tasks. The fourth characteristic, agreeableness, expresses that people are not rude to others, that they can forgive and that they are considerate and kind to others. Individuals who are easily worried, who are nervous in many situations, who do not easily relax and who cannot cope well with stress exhibit the fifth trait, neuroticism. The opposite of the latter is emotional stability.

4 Methods and econometric results

4.1 Empirical strategy

The main dependent variable in our analysis is HEALTH. As this is an ordered variable with five categories, an ordered probit model is estimated. As a first approximation, OLS estimates can be applied. We are especially interested in the influence of personality traits and job characteristics. Unfortunately, health behaviors are not available in the LPP data.

We start with three separate estimates. First, regressors are incorporated that are usually used in health economics studies as control variables, such as wages, fixed-term work, working hours, skill-based socioeconomic status and training (Caroli and Weber-Baghdiguian 2016). Second, the Big Five variables and other personal characteristics, such as age, gender, education and nationality, are used as regressors (Dahmann and Schnitzlein 2017; Jürges 2008). Third, we investigate the influence of job characteristics on health.

In the next step, we combine all these determinants (Table 4, column 4). Based on the first three estimates (columns 1–3), we select those determinants that have a significant influence on health. As two alternative selection procedures, we apply the least angle regression (LARS) developed by Efron et al. (2004) and the robust least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (RLASSO) developed by Belloni et al. (2012). The latter allows for estimation under heteroskedastic, non-Gaussian and clustered disturbances (RLASSO). The results are in columns 5 and 6 of Table 4. We test the goodness of the model fit with the Breusch-Pagan test for heteroskedasticity and with Ramsey’s (1969) RESET approach. Furthermore, we assess whether multicollinearity is a problem by using the variance inflation factor (see Table 6). Analogous to the HEALTH estimates, we present in Tables 5 and 6 the results for MENTAL health and ABSENT.

Further investigations are devoted to interaction effects between job and personal characteristics. We model interaction effects using a difference-in-differences (DiD) model with dummy variables. An extension of two-way DiD is triple DiD, where the former is a special case of the latter. This means that for the general triple DiD case, we estimate the following:

where y is HEALTH; w, x and z are dummies, in our case using observed health determinants, JC5_D, COM6_D and NEURO_D; u is the error term. The symbol _D indicates dummy variables. The coefficient γ7 corresponds to the triple DiD effect:

The two-way DiD follows if z = 0, resulting in the following:

The coefficient γ4 is the simple DiD effect. The analysis of interaction effects is a wide field. A priori, many interactions could be relevant. We restrict our investigations to significant main and interaction health determinants based on Table 7 and further preliminary inquiries.

Thus far, we have assumed that all of our health determinants are exogenous with respect to health. However, for many regressors, there are arguments for endogeneity. It is impossible to model, estimate and test all these possibilities. Our strategy is to ignore reverse causality, as the literature thus far has not presented credible instruments for health; alternatively, we make assumptions that follow the literature and exclude reverse causality, or we restrict endogenous modeling to variables for which endogeneity was documented in other empirical studies or by plausible and substantial arguments. We do not have information in our database to test all hypotheses regarding potential endogeneity in our models.

One important worker-related health factor with possible endogeneity is wages. On the one hand, increases in income can increase expenditures on health. On the other hand, good health contributes to better performance and consequently to higher income. If the null hypothesis that individual wages are exogenous with respect to health is rejected, the average establishment wage per employee can be used as an instrument. As this is not an entirely convincing instrument, we follow the approach in Lewbel (2012) for endogenous treatment effects, where only generated instruments are used at first (Table 8, column 2). Cragg–Donald’s (1993) test statistic is compared with Stock and Yogo’s (2005) critical value for α = 0.05. Then, we extend the approach by using the average establishment wage per employee as an external instrument (Table 8 column 3).

Lewbel’s technique enables the identification of structural parameters in fully simultaneous linear models, such as

under the assumptions that x and e are uncorrelated, that the error terms e are heteroskedastic and that the covariance between z and the product e1e2 is zero. In our case, Y1 is the health variable and Y2 is the log wage. The vector z contains observed variables, which can be discrete or continuous, and it can be a subset of x. In the latter case, no information outside the model specified above is required. If the covariance assumption is violated, then the parameters are still identified if the correlation between z and e1e2 is smaller than the correlation between z and e22. Identification comes from a heteroskedastic covariance restriction and is achieved by having independent variables that are uncorrelated with the product of the heteroskedastic errors. In the simplest version, instruments W can be generated as the product of the residuals from the reduced form and the mean-centered values (Z-mean(Z)) of an element of vector z as a subset of x.

In one sense, this approach is a generalization of Altonji and Shakotko (1987), where time-demeaned centered variables are used as instruments. The advantage of Lewbel’s method is that weighting with e2 reduces the risk of a correlation between instruments and the error term of the above Y1 equation. “The structural parameters β1 and γ1 (of a triangular model) are identified by an ordinary linear two-stage least squares estimation of Y1 on x and Y2 using x and (Z − mean(Z))e2 as instruments. The assumption that Z is uncorrelated with e1e2 means that (Z − mean(Z))e2 is a valid instrument for Y2 in the (main) equation since it is uncorrelated with e1, with the strength of the instrument (its correlation with Y2 after controlling for the other instruments x) being proportional to the covariance of (Z − mean(Z))e2 with e2, which corresponds to the degree of heteroskedasticity of e2 with respect to Z (Lewbel 2012, p. 70). The greater the degree of heteroskedasticity in the error process, the higher the correlation of the generated instruments with the included endogenous variable Y2 in the first (main) regression will be.

The causal relation between personality traits and health is not clear-cut. The discussion of this relationship is ongoing, but the majority of scholars assume that the Big Five are stable in adulthood (Cobb-Clark and Schurer 2012; Rantanen et al. 2007). Here, no endogeneity investigations are necessary. We argue that graduation and completion of training are important milestones for adulthood and therefore consider the age of 25 to be a good cutoff for Germany. We investigate whether the empirical evidence confirms this. The literature also discusses important positive and negative life events that lead to changes in personality traits. Anger et al. (2017) find that involuntary job loss following a plant closure leads to an increase in openness for the average displaced worker and, to some extent, to a change in emotional stability, whereas the other dimensions of the Big Five personality inventory remain unchanged. We cannot test this finding with our data, but we assume that none of the respondents recently experienced an involuntary job loss, as their average tenure is rather high.

A final question regards the endogeneity between working conditions and health. For example, we can suppose not only that physically demanding work has negative consequences on health status but also that workers with poor health do not perform physically demanding activities. Reverse causality is also plausible between collegiality and health. Problems with colleagues negatively affect one’s own health, but poor health in combination with negative mood is also not conducive to relationships with colleagues. We test for this in the relationship between JC5 and HEALTH (Table 8, column 4) on the one hand and between COL3 and HEALTH (Table 8, column 5) on the other hand. In these two cases, we also apply Lewbel’s approach. The firm averages for JC5 and COL3 are added as external instruments for the employee-level variables.

The results for different subsamples are presented in the Appendix (Tables 10, 11, 12). The intention is to show whether the effects on health are robust.

4.2 Estimation results

The first estimates in Table 4 show that many of our incorporated variables in columns 1–3 have a highly significant influence on HEALTH. As expected, personal characteristics, especially age, are negatively correlated with good health status, and high-quality schooling is positively correlated with good health status. We want to highlight that conscientiousness, agreeableness and emotional stability contribute to good health as well. Workers, who have no decision-making power at work, engage in physically strenuous work, face unpleasant environmental conditions and time pressure, and have multitasking requirements have more health problems than other workers do. These findings also hold for employees who do not receive help when needed from their colleagues and who are often unfairly criticized by their colleagues and supervisors. Former empirical studies have not investigated these relationships. We observe that employees with a permanent contract have worse health, which may be related to their older age and unobserved characteristics, e.g., unobserved abilities.

It is reasonable to combine these partial approaches, the results of which are presented in column 4. The results confirm those of columns 1–3. We find the same sign and a similar significance level with the following exceptions: craftsmen do not have worse health than masters do. The effects of part-time work and working hours are also insignificant. Working from home leads to worse health. The influence of basic sociodemographic variables on health declines if job characteristics, commitment and collegiality are incorporated (compare column 4 with column 1).

As alternatives to the approach used in column 4, LARS and RLASSO estimations in columns 5 and 6 provide robustness checks for variable selection. The results are similar with respect to the sign and significance. RLASSO selects fewer regressors than the combined approach in column 4, but the combined approach is a leaner model than that in column 5. Thus, column 4, which includes only the significant determinants of health reported in columns 1–3, seems to be a good compromise between LARS and RLASSO. Remarkably, however, RLASSO only reveals neuroticism as a relevant health determinant from among the Big Five items, while the other two selection procedures also find that conscientiousness and agreeableness determine health. Regarding working conditions, all three selection procedures show the following: workers who have decision-making power, are not engaged in physically demanding work, have pleasant environmental conditions and receive frequent help from colleagues when needed have, on average, better health than others do. Those who are unfairly criticized by colleagues and supervisors describe their health as poor. In the following, we focus our discussion on the results of the combined approach as a compromise between the LARS and RLASSO approaches.

Table 5 shows the influence of personal and job characteristics on MENTAL health. In comparison with Table 4, we find, on the one hand, that the basic sociodemographic variables are less important and, on the other hand, that the effects of personal characteristics are more often significant. The importance of job characteristics is equally essential for HEALTH and MENTAL health; however, the impact pattern differs. It is not surprising that physically demanding work has negative effects on physical health, while its effect on mental health is only weakly significant. Job commitment is crucial for mental health, while for physical health, the model estimates only a weak influence from COM3 (Table 4, column 4). Collegiality is positively correlated with good physical and mental health.

The measurements of HEALTH and MENTAL health are based on a subjective evaluation. With our data, we can use only one objective self-reported health variable as a robustness test, namely, the number of working days per year in which an employee was absent due to illness (ABSENT). The correlation coefficients between the three health indicators are presented in Table 1.

The same specifications as in Table 4 are estimated with ABSENT as the dependent variable. Table 6 shows the results. We compare column 4 in Table 4 with that in Tables 5 and 6. In most cases, the signs are the same, especially for the JC variables. The correlations between the Big Five variables and ABSENT are less clear than those with HEALTH and especially with MENTAL health. The signs differ in some cases. Thus, we prefer the measure of HEALTH for the following analyses.

The next discussion of estimation results is devoted to interaction effects. Among the large number of possible interactions between dummy variables, e.g., JC1_D*JC7_D, where JC1_D = 1 if (JC1==1| JC1 = = 2) and JC1_D = 0 if JC1>2 and analogously JD7_D, we find only a few combinations that reveal a significant impact on HEALTH. The estimates of three two-way interaction models are presented in Table 7 in columns 1–3. The results are as follows:

-

(1)

Workers with strong decision-making authority (JC1_D = 1) usually have good health, while those who often face high deadline pressures (JC7_D = 1) have poorer health. The latter influence is moderated under JC1_D*JC7_D = 1. This is in accordance with Karasek (1979) who found that a combination of low levels of decision-making autonomy and heavy job demands is associated with mental strain.

-

(2)

Workers who get help when needed from their colleagues are usually in a better state of health than the average employee. This relationship is weakened if they are neurotic (COL1*NEURO_D = 1).

-

(3)

Extroverted workers (EXTRA_D = 1) have, on average, a better state of health than other employees. This link is weaker if they are often unfairly criticized by colleagues and supervisors (COL3*EXTRA_D = 1).

Estimates of triple DiD effects are usually insignificant. Column 4 shows an exception. Explicitly modeling the combination between JC7_D, COM6_D and COL3_D seems helpful. The combination of receiving unfair criticism by colleagues and supervisors, facing deadline pressure, having to multitask and lacking a commitment to the firm, contributes to weakening the negative health effects of the main and simple interaction factors.

The influence of the triple interaction variable JC5_D*COM6_D*NEURO_D on HEALTH is positive if all three dummies are equal to one (see column 5 (IA3_2) of Table 7). However, the effect is only weakly (α < = 0.10) significant. A priori, we had no clear-cut expectations about the sign on this effect. We have to consider the complete interaction model. The main effects of JC5_D, COM6_D and NEURO_D on HEALTH are negative; that is, low emotional stability is connected to poor health. The two-way interaction between neuroticism and physically demanding work on the one hand and low commitment to the firm on the other hand on HEALTH exhibit the opposite sign. Finally, the sign of the three-way interaction JC5_D*COM6_D*NEURO_D is negative. This means, among others, that the negative two-way interaction effect between JC5 and NEURO_D is stronger if the employee has no commitment to the company.

Although we find few significant triple interaction effects, we must stress that personal, job and other health determinants have joint influences. Some of these combined influences increase and others decrease the main effects.

Ramsey’s RESET does not reject the null hypothesis that the model is correctly specified—see Table 8, line RESET. However, we reject homoskedasticity (see line Breusch-Pagan) and the exogeneity of wages (see line Hausman). Multicollinearity does not seem problematic (see line VIF). Lewbel’s approach with generated instruments only (Table 8, column 2) leads to estimates similar to those in column 1, especially those for the Big Five, commitment, collegiality and job characteristics. We should stress that the influence of wages is now insignificant. If the instrument “average establishment wage per employee” is added (see column 3), there are no remarkable changes for significant regressors in comparison with column 2. In both cases, we reject the null hypothesis of weak instruments (see line Cragg-Donald).

In Sect. 4.1, we formulated the hypothesis that the variables JC5 and COL3 indicate mutual dependencies with HEALTH, thereby leading to endogeneity. This is not (or is only weakly) supported by our estimates and tests in columns 4 and 5 of Table 8. Wages are an endogenous regressor with respect to health. For the other two variables specified in Sect. 4.1 (JC5 and COL3), the test outcome is less clear cut. Random effects estimates are presented in Bellmann and Hübler (2019). Fixed effects models are not estimated due to the largely time-invariant personal attitudes captured in our data. Industries and firm size classes are considered in robustness checks for alternative instruments—see the Appendix, Table 9. Occupations are only incorporated in a simple, strongly aggregated form, namely, by occupational position: unskilled, craftsman, foreman and master. An alternative categorization is forms of job training. The results are similar to the former, and therefore, these results are not shown. Detailed occupations are not available in our data set. In the Appendix, Tables 10, 11, and 12, we present estimates for subgroups and discuss the degree of robustness.

5 Summary and conclusion

Conventional health determinants are important and should be considered in empirical analyses investigating their association with the individual’s health. Our comprehensive study provides greater confidence in these established results. In addition, we also generate novel insights: specific personality traits, as well as job characteristics, substantially supplement our knowledge of individual health status. Our estimates correct the bias caused by the omission of relevant variables so that the seemingly clear influence of being an unskilled worker or craftsman and the influence of training variables is reduced. The impact of other variables, such as age and fixed-term employment, does not change fundamentally. A priori, it was unclear which personality traits and job conditions would be influential on physical health. We can now infer from our results that among the Big Five variables, openness and extraversion are less important, while the other variables have a strong impact. For mental health, all Big Five items are influential, while the effects of these items on the number of working days missed because of sickness were not statistically significant, except in cases of neuroticism. In addition, not all recorded job characteristics are important. Thus, the variables used exert differential influences on the three health variables.

Whether the work of other colleagues depends directly on one’s own work and whether one’s own tasks depend on the work of other employees seem irrelevant for one’s own health. Unpleasant environmental conditions at work and physically demanding activities have a negative influence on health. A negative influence is also present for those working under time pressure and for whom multitasking is required. No clear statement about the effects of job commitment on health is possible with our estimates, with the exception of effects on mental health. Those who have a strong commitment to their firm usually do not experience mental health problems, while those who often perceived themselves to be unfairly criticized by colleagues and supervisors report a typically worse health status than others do.

These major results are confirmed when alternative models are estimated and different econometric methods are applied, thus providing evidence in favor of robustness. Interaction effects between job characteristics on health are detected in only a few cases. Instrumental variable estimates that take into account the endogeneity of wages show that this problem is relevant. However, the influence of personal attitudes and job characteristics on health is not affected. We refrain from giving a causal interpretation of our results.

Companies, their owners and their managers are interested in employee health. They try to improve or safeguard health by offering sports courses, by improving job conditions and by taking into account the personality of their staff when planning labor inputs. So far, it is not always clear which conditions are the most important and which attitudes can be neglected. Our investigations show that firms should avoid requiring physically demanding work and providing unpleasant environmental conditions. Furthermore, time pressure and multitasking should be limited. Personality traits have a strong impact on individual health, especially on mental health, even when a large set of other variables is included in the regression models. In the future, the focus of research should shift more toward these aspects, particularly by using alternative empirical sources. A more detailed breakdown into worker and company groups should follow. A longitudinal perspective and analyses taking into account firm-level variables are recommended.

References

Altonji JG, Shakotko RA (1987) Do wages rise with seniority? Rev Econ Stud 54(3):437–459

Anger S, Camehl G, Peter F (2017) Involuntary job loss and changes in personality traits. J Econ Psychol 60:71–91

Antonovsky A (1979) Health, stress and coping. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Bachelet M, Becchetti L, Ricciardini F (2015) Not feeling well… (true or exaggerated?) health (un)satisfaction as a leading health indicator. CEIS Tor Vergata, Research Paper Series, Vol. 13, Issue 2, No. 336.

Bacolod M, Cunha JM, Shen YC (2017) The impact of alcohol on mental health, physical fitness and job performance, NBER working paper 23542.

Baker M, Stabile M, Deri C (2004) What do self-reported, objective, measures of health measure? J Human Resources 39:1067–1093

Bakker AB, van Veldhofen M, Xanthopoulou D (2010) Beyond the demand-control model: thriving on high job demands and resources. J Personnel Psychol 9(1):3–16

Barcellos SH, Carvalho LS, Turley P (2018) Distributional effects of education on health, USC Dornsife, CESR-Schaeffer DP 2018–002.

Beemsterboer W, Steward R, Goothoff J, Nijhuis F (2009) A literature review on sick leave determinants (1984–2004). Int J Occup Med Environ Health 22(2):169–179

Bellmann L, Hübler O (2019) Personal attitudes. Job Characteristics and Health, IZA DP No, p 12597

Belloni A, Chen D, Chernozhukov V, Hansen C (2012) Sparse models and methods for optimal instruments with an application to eminent domain. Econometrica 80(6):2369–2429

Broszeit S, Grunau P, Wolter S (2016) LPP—Linked Personnel Panel 1415, FDZ-Datenreport 06/2016, Nürnberg.

Broszeit S, Wolter S (2015) LPP – Linked Personnel Panel – Arbeitsqualität und wirtschaftlicher Erfolg: Längsschnittstudie in deutschen Betrieben (Datendokumentation der ersten Welle), FDZ-Datenreport 01/2015, Nürnberg.

Caroli E, Weber-Baghdiguian L (2016) Self-Reported Health and Gender: The Role of Social Norms. IZA DP No. 9670.

Case A, Paxson C (2002) Parental behavior and child health. Health Aff 21:164–178

Cawley J, de Walque D, Daniel Grossman D (2017) The effect of stress on later-life health: evidence from the Vietnam draft, NBER Working Paper 23334.

Chen L-S, Wang P, Yao Y (2017) Smoking, health capital, and longevity: evaluation of personalized cessation treatments in a lifecycle model with heterogeneous agents. NBER Working Paper No. 23820.

Cobb-Clark D, Schurer S (2012) The stability of big five personality traits. Econ Lett 115(1):11–15

Coenen P, Huysmans MA, Holtermann A, Krause N, van Mechelen W, Straker LM, van der Beek AJ (2018) Do highly physically active workers die early?—a systematic review with meta-analysis of data from 193 696 participants. Br J Sports Med 52(20):1320–1326

Cragg JG, Donald SG (1993) Testing identifiability and specification in instrumental variable model. Economet Theory 9:222–240

Dahmann SC, Schnitzlein DD (2017) The protective (?) effect of education on mental health, mimeo.

De Bruin GP, Taylor N (2006) The job demand-control model of job strain across gender. J Ind Psychol 32(1):66–73

De Jonge J, Kompier MAJ (1997) A critical examination of the demand-control-support model from a work psychological perspective. Int J Stress Manage 4(4):235–258

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB (2001) The job demands resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol 86(3):499–512

Efron B, Hastie T, Johnstone I, Tibshirani R (2004) Least angle regression. Ann Stat 32(2):407–451

Fernández-Val I, Savchenko Y, Vella F (2013) Evaluating the role of individual specific heterogeneity in the relationship between subjective health assessments and income, IZA DP No. 7651.

Fila MJ, Purl J, Griffeth RW (2017) Job demands, control and support model: meta-analyzing moderator effects of gender, nationality, and occupation. Human Resource Manag Rev 27:39–60

Fletcher JM, Sindelar JL, Yamaguchi S (2011) Cumulative effects of job characteristics on health. Health Econ 20(5):553–570

Frankenberg E, Thomas D (2017) Human capital and shocks: evidence on education, health and nutrition, NBER Working Paper 23347.

Giuntella O, Mazzonna F (2016) If You Don’t Snooze You Lose: Evidence on health and weight, IZA DP No. 9773.

Gonsalves, Martins PS (2018) The effect of self-employment on health: evidence from longitudinal social security data, IZA DP 11305.

Häusser J, Mojzisch A, Niesel M, Schulz-Hardt S (2010) Ten years on: a review of resent research on the Job Demand-Control (-Support) model and psychological well-being. Work and Stress 24(1):1–35

Hübler O (2017) Health and weight—gender-specific linkages under heterogeneity, interdependence and resilience factors. Econ Human Biol 26:96–111

Johnson JV, Hall EM (1988) Job strain, work place social support and cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am J Public Health 78:1336–1342

John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL (1991) The Big Five Inventory—versions 4a and 5. University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research, Berkeley CA

Jürges H (2008) Self-assessed health, reference levels and mortality. Appl Econ 40:569–582

Kain K, S. Jex (2010) Job demands-control model: A summary of current issues and recommendations for future research. In: Perrewe PL, Ganster DC (eds) New developments in theoretical and conceptual approaches to job stress Bingley. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, UK, pp 237–268

Kampa M, Castanas E (2008) Human health effects of air pollution. Environ Pollut 151:362–367

Karasek RA (1979) Job demands. Job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Admin Sci Quart 24(2):285–308

Kelly CW (2008) Commitment to health theory. Res Theory Nursing Pract 22(2):148–160

Lewbel A (2012) Using heteroscedasticity to identify and estimate mismeasured and endogenous regressor models. J Bus Econ Stat 30(1):67–80

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP (2001) Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 52(1):397–422

Maestas N, Mullen KJ, Powell D, von Wachter T, Wenger JB (2018) The Value of Working Conditions in the United States and Implications for the Structures of Wages, NBER Working Paper 25204.

Misra S, Stokols D (2012) Psychological and health outcomes of perceived information overload. Environ Behav 44(6):737–759

Papageorge NW, Pauley GC, Cohen M, Wilson TE, Hamilton BH, Pollak RA (2016) Health, human capital and domestic violence, NBER Working Paper 2288.

Pikos AK (2017) The causal effect of multitasking on work-related mental health - the more you do, the worse you feel. Leibniz Universität Hannover, Discussion Paper, p 609

Prümer S, Schnabel C (2019) Questioning the Stereotype of the “Malingering Bureaucrat”: absence from Work in the Public and Private Sector in Germany, IZA Discussion Paper No. 12392.

Ramsey JB (1969) Tests for specification error in classical linear least squares regression analysis. J Roy Stat Soc B31:350–371

Rantanen J, Metsäpelto R-L, Feldt T, Pulkkinen L, Kokko K (2007) Long-term stability in the Big Five personality traits in adulthood. Scand J Psychol 48:511–518

Reinecke L, Aufenanger S, Beutel ME, Dreier M, Quiring O, Stark B, Wölfing K, Müller KW (2017) Digital stress over the life span: the effects of communication load and internet multitasking on perceived stress and Psychological Health impairments in a German probability sample. Media Psychol 20(1):90–115

Rydstedt L, Devereux J, Sverke M (2007) Comparing and combining the demand-control-support model and the effort reward imbalance model to predict long-term mental strain. Eur J Work Organizational Psychol 16(3):261–278

Savelyev P, Tan KTK (2019) Socioemotional skills, education, and health-related outcomes of high-ability individuals. Am J Health Econ 5(2):250–280

Seltenrich N (2015) Between extremes: health effects of heat and cold. Environ Health Perspect 123(11):A275–A279. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.123-A275]PMCID:PMC4629728

Stansfield S, Crombie R (2011) Cardiovascular effects of environmental noise: Research in the United Kingdom. Noise & Health 13:229–233

Stock JH, Yogo M (2005) Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In: Andrews DWK, Stock JH (eds) Identification and inference for econometric models: Essays in honor of Thomas Rothenberg. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 80–108

Wehner C, Schils T, Borghans L (2016) Personality and mental health: The role and substitution effect of emotional stability and conscientiousness, IZA DP 10337.

Westgaard RH, Winkel J (1997) Ergonomic intervention research for improved musculoskeletal health: a critical review. Int J Ind Ergon 20:463–500

Acknowledgements

We thank Silke Anger, Michael Beckmann, Knut Gerlach, Marie-Christine Laible, Malte Sandner and Daniel Schnitzlein for helpful comments as well as the participants of the annual meeting of the research group of Labour and Socio Economic Research (LASER) and the presentation in DiskAB.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Alternative instruments and subgroups analysis

Appendix: Alternative instruments and subgroups analysis

Instead of firm dependent instrumental variables we apply in Table 9 alternative instrumental variables as robustness checks because social interaction with co-workers, a worker's health can be affected by his/her co-worker's characteristics. For example, high collegiality of co-workers could affect a worker's health positively. This would violate the exclusion restriction for average firm collegiality as an IV for a worker's own collegiality. As instrumental variables we use in Table 9 the average (log) wage, the average degree of physically demanding activities (JC5) or the average level of criticism (COL3) within the firm size class or the industry to which the worker belongs; 5 firm size classes (1–20, 21–200, 201–500, 501–2000, 2001 or more employees) and 14 industries are distinguished based on the German IAB Establishment Panel 2012, 2014 and 2016. The estimates show very similar results in comparison with Table 8, columns 3–5. This speaks in favor of the validity of the results in Table 8, 3–5. We have also experimented with averages of interactions between firm size classes and industries. The results are not presented in the Tables because the results do not differ from those where only averages of industries are used.

As further supplement we present subsample estimates—see Tables 10, 11, and 12. We distinguish between employees of different age groups (Table 10), between employees that work in establishments of the manufacturing or service sector, or that live in eastern or western Germany (Table 11). We also distinguish between different firm size classes (Table 12).

The estimates in columns (2) to (4) of Table 12 show that the influence of the Big Five variables on HEALTH is very similar for employees older than 25 years or for prime age workers compared to the total sample, while the results for younger workers have a different pattern. This supports the assumption that for adults personality traits are fixed. Further, the variability of personality traits in adolescence has no strong impact on their relationship with HEALTH in the full sample including the whole age range. During adolescence conscientiousness has no influence on HEALTH.

Within all considered subgroups neuroticism is significantly disadvantageous for health, while conscientiousness has a positive influence for adults. Jobs with unpleasant environmental conditions are not favorable for health. In the manufacturing sector and in eastern Germany in contrast to other subgroups, we do not find that time stress and multitasking have a significant negative influence on health. If workers have no emotional commitment to the establishment, their health status is worse than for those with emotional commitment, both in the total sample and in subgroups. However, the statistical effects are insignificant in most investigated cases. We are not surprised that workers who feel unfairly criticized by colleagues and supervisors have worse health than others.

Remarkable differences between small and large firms (1–9; ≥ 500 employees) should be highlighted for JC1, JC5, JC7, COL1 and COL3. Among others, unpleasant working conditions in large firms have significant negative effects on workers’ HEALTH. This is not confirmed for workers in small firms. We find the opposite result with respect to time pressure and multitasking. In small firms workers suffer under these job conditions with the consequence of worse health while in large firms no negative health effects are evident. Collegiality, measured by COL1, supports the workers’ health status in large firms. In small and especially in middle-sized establishments we observe that health is negatively correlated with unfair criticism (COL3).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bellmann, L., Hübler, O. Personality traits, working conditions and health: an empirical analysis based on the German Linked Personnel Panel, 2013–2017. Rev Manag Sci 16, 283–318 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-020-00426-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-020-00426-9