Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to determine how an early occupational therapy (OT) intervention affected hospital length of stay (LOS) in a sample of patients with a moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Methods

This quasi-experimental study was conducted with 2018–2020 data from a rehabilitation center at the King Saud Medical City in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The sample of 29 TBI patients included 15 experimental (prospective) group participants who received an early OT intervention and 14 control group (retrospective) participants who did not receive the intervention. The intervention provided patients with daily OT therapy based on their needs and was divided into two phases: the intensive care unit (ICU) phase and the general ward phase. The following measures were used: Glasgow Coma Scale score at admission (both groups), hospital LOS (from admission until discharge; both groups), and functional independence measures (FIM) at admission and discharge (experimental group).

Results

Experimental group patients had a much shorter LOS (average 61.53 days) compared with the control group (mean 108.86 days). Additionally, the experimental group had a statistically significant increase in FIM scores from admission to discharge.

Conclusions

These results suggest that providing early OT interventions to patients with moderate and severe TBIs can help decrease their LOS, which can contribute to reduced treatment costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI)—which can lead to life-long disability and death—is a serious global public health problem [1], with approximately 1.5 million Americans sustaining a TBI each year [2]. TBI also was predicted to become the third cause of global mortality and disability by 2020 [3]. In Saudi Arabia, TBI incidence has been extrapolated to be 116 per 100,000 of the population [4].

As with most neurological injuries, TBI patients require rehabilitation services. Several treatment modalities are available, which are prescribed based on several variables. These variables include injury severity (mild, moderate, or severe), patient age, injury site, initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) rating, computerized tomography scan findings associated with skeletal trauma (intracranial bleeding and skull fracture), length of acute hospitalization, and the presence of an extremity fracture (e.g., long bone, hip, and shoulder girdle fractures) [5]. These factors also significantly affect patients’ length of stay (LOS) [6], which in turn can influence their recovery and treatment costs.

Background

Many studies have investigated the importance of rehabilitation for TBI patients. In their study, Lenze et al. highlighted the need to improve the quality of patients’ participation in rehabilitation sessions [7]. That study used a validated measure for clinician-rated disability assessment for inpatient rehabilitation, which uses a 6-point Likert-type scale [7]. Those findings indicated that LOS is highly dependent on the quality of patients’ participation during therapy sessions [7]. Furthermore, the findings revealed that poor participation in inpatient therapy sessions was common, was associated with longer inpatient rehabilitation stays, lowered the likelihood of discharge to home, and led to poorer functional outcomes in those with frequent poor participation [7].

By contrast, research has shown that effective rehabilitation can help maximize TBI patients’ level of recovery and functionality in the activities of daily living (ADLs). Some studies have focused on how early rehabilitation admission affects LOS [8], whereas others have investigated the critical factor of rehabilitation program intensity. One study indicated that beginning an intensive rehabilitation as soon as patients are medically stable after an injury and continuing it from that point on can improve rehabilitation outcomes significantly [9]. Lippert-Gruner et al. highlighted the importance of early and continuous rehabilitation for TBI patients [10]. In fact, 91.6% of that study’s population were almost independent in completing ADLs at their follow-up examination at 12 months posttrauma [10]. Conversely, rehabilitation delays have been shown to result in poor functional outcomes. Griesbach et al. assessed whether delays between injury onset and rehabilitation program admission influenced outcomes [11]. Those results determined that rehabilitation benefits are missed when the period from injury onset to rehabilitation admission was longer than 1 year [11]. Other researchers found that an early intense and structured rehabilitation intervention delivered by trained rehabilitation teams can promote motor recovery, functional recovery, and reduced hospital LOS [12]. In alignment with those findings, Cope and Hall determined that the LOS for TBI patients admitted to rehabilitation later than 1 month after injury was twice that of those admitted during the first month after injury [13]. Furthermore, LOS has been found to increase approximately 1 day for every 5–7 days of delay to rehabilitation admission, which also increases treatment costs [8].

In an Italian study exploring variables associated with rehabilitation LOS in 241 TBI patients, Arango-Lasprilla et al. found that long acute care LOS was independently associated with a significantly longer rehabilitation LOS [5]. Conversely, shorter acute care stays were independently associated with shorter rehabilitation stays [5]. In summary, these articles clarify the positive correlation between rehabilitation admission delays and longer LOS in TBI patients.

Regarding TBI patients in Saudi Arabia, one study assessed the link between the length of time from injury to rehabilitation admission and LOS for patients arriving from acute care and other settings [14]. The results indicated that the period from injury to rehabilitation admission for patients arriving directly from acute care to rehabilitation was one-third that of patients arriving from other settings [14]. Nevertheless, the LOS in rehabilitation was almost the same between patients who came directly from acute care and those from other settings [14].

Rationale and purpose

Our literature review uncovered studies about the enhanced effectiveness of occupational therapy (OT) services that started at an early injury stage. However, the majority of these studies focused on general rehabilitation (physiotherapy, OT, etc.) without considering each team individually. Moreover, given the scarcity of OT services in intensive care units (ICUs) in many hospitals and healthcare facilities, there is a corresponding lack of studies focusing on OT effectiveness in the ICU.

Delaying OT interventions for TBI patients during the acute injury phase forces occupational therapists to focus on addressing complications rather than restoring ADL skills and independence. These complications can include pressure ulcers, deep venous thrombosis, heterotopic ossification, joint calcification, muscle weakness, and limited range of motion (ROM). By contrast, beginning rehabilitation early can help prevent further complications while maximizing rehabilitation outcomes [15]. Thus, this study aimed to determine how an early OT intervention affected hospital LOS in a sample of TBI patients in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA).

Methods

Setting

This quasi-experimental study was conducted at the OT department of a rehabilitation center within the King Saud Medical City (KSMC) in Riyadh, KSA. KSMC is a trauma center serving the entire KSA that has a 1400-bed capacity, with an average of 70 beds occupied by TBI patients.

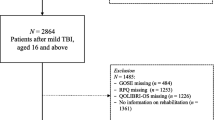

Participants

The 29 patients in this study sample were admitted to the ICU at KSMC in Riyadh between 2015 and 2020. The participants were divided into control and experimental groups. The randomly chosen control group was a retrospective sample of 14 patients admitted and discharged before 2018. The experimental group was a prospective sample of 15 patients admitted and discharged between 2018 and 2020.

The inclusion criteria were patients > 14 years of age who had a moderate to severe TBI related to trauma, had a GCS score between 3 and 13, and were referred to the OT department during the first 2 weeks after injury. The exclusion criteria were patients ≤ 14 years of age, those referred from other hospitals, and those referred to the OT department after 2 weeks from the injury date. Additionally, patients with neurological conditions and disorders that reduced their functional independence measure (FIM) scores were excluded (e.g., epilepsy, depression, DVT, dementia, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, poly trauma, and upper limb fractures).

Measures

The following measures were used for this study: GCS score at admission (both groups), hospital LOS (from admission until discharge; both groups), and FIMs at admission and discharge (experimental group only, as the hospital did not record FIM during that period). The GCS “is a neurological scale aiming to provide a reliable, objective way of recording the conscious state of a person, both for initial and continuing assessment of the patient, which has a special value in predicting the ultimate outcome” [16]. This 3–15-point instrument is used to assess a patient’s level of consciousness and neurological function [17] and is the most commonly used classification system for determining TBI severity at the time of injury. The scale consists of three sections: best motor response, best verbal response, and eye opening. In the GCS classification system, a score of 3–8 indicates a severe TBI, a score of 9–13 indicates a moderate TBI, and a score of 14–15 indicates a mild TBI [18].

The FIM is an 18-item, clinician-reported scale that assesses function in six areas: self-care, continence, mobility, transfers, communication, and cognition [19]. Each of the 18 items is graded on a scale of 1–7 based on the patient’s level of independence in that item (1 = total assistance required, 7 = complete independence) [19]. Occupational therapists can measure inpatients’ FIM scores at admission and discharge. The difference between these two scores constitutes the FIM change or gain. The term FIM efficiency refers to the rate of FIM change over time [19].

Early OT intervention

For the intervention, an occupational therapist developed a plan of care based on the patient’s assessment results and then provided daily sessions (lasting 30–45 min) based on patient needs. The patients received OT interventions 5 days a week (weekdays). Nurses and caregivers were given instructions to ensure the continuation of the therapy plan during weekends. The intervention was divided into two phases: the ICU phase and the general ward phase. The main goals for both stages of intervention were to help patients achieve their maximum possible level of independence in ADL (functional outcomes) and reduce their LOS.

ICU phase

The intervention’s ICU stage is aimed at preventing deformity as well as promoting and maintaining proper positioning and normal ROM. The ICU intervention included positioning; splinting and splint fitting; ROM exercises for all upper limb joints; edema management; orientation and arousal level stimulation; muscle tone management exercises; and intervention education and training for nurses, staff, and family members.

General ward phase

When patients were deemed medically stable by the primary care team, they were transferred to a general ward where occupational therapists provided a wide range of interventions depending on their needs. These interventions aimed to increase patients’ independence in ADL and prepare them for discharge by supporting their physical, cognitive, psychological, and social recovery. The services provided included sensory re-education training; passive and active ROM exercises for the upper limbs; splint fitting schedules; stretching and high muscle tone reduction techniques; upper limb strengthening exercises; rolling exercises; static and dynamic sitting balance exercises; transfer training; patient and family education (techniques and safety concerns); ADL training; instrumental ADLs (IADLs); advanced cognitive activities; and assistive device services.

Data collection

The data collected for the control group (participants admitted and discharged before 2018) were age, GCS at admission, and LOS. These were the only data available for these participants because there were no early OT interventions for TBI patients (especially in the ICU) during that period because of a lack of occupational therapists at KSMC.

The additional data collected for the experimental group were the dates of injury, hospital admission, and referral to the OT department. These dates were recorded to ensure that there was no delay in patients receiving the OT intervention. FIM scores at admission and discharge also were collected for the experimental group.

Ethics

This study was approved by the requisite Institutional Review Board, (I) (H1RI-24-Oct18-01). The confidentiality of the data was maintained according to national bioethics rules and regulations.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (Armonk, NY; IBM Corp). Categorical variables (gender, GCS at admission) are presented as frequency, percentage, and continuous variables. The variables of age, GCS at admission, FIM at admission, day of referral, FIM at discharge, and LOS are presented as mean, standard deviation, range, and 95% confidence interval. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to examine the normality of the values. The parametric test t-test was used to determine any statistically significant differences between the two groups, Paired t-test for the FIM score at admission and discharge and Spearman’s coefficient of correlation was used to determine any relationship between the FIM and LOS values as LOS did not satisfy the assumption of normality. The nonparametric independent-sample Mann–Whitney U test was used to examine differences in Hospital LOS between the group’s values. The related sample Sign test was used for the distribution of free data. All these tests were applied and observed, with statistical significance set at the 5% level.

Results

Gender and age

The experimental group included 13 males and 2 females, whereas the control group had 13 males and one female. The age of control group patients ranged from 19 to 72 years, with a mean of 35.4 years. The age of experimental group patients ranged from 16 to 52 years, with an average of 32 years. The age distribution histogram of the 29 participants indicated that the majority were between 20 and 55 years of age.

GCS at admission

Figure 1 shows the GCS scores at admission for all participants. Although there was a small variation (0.11) in the groups’ means (control group, 6.64; experimental group, 6.53), there were no between-group differences in the median value (7.00 for both groups). The minimum and maximum GCS scores were 3 and 13 for the control group and 4 and 11 for the experimental group. The homogeneity of the GCS data for both groups indicated that the participants had similar injury severity.

FIM at admission and discharge

The experimental group’s mean FIM score improved significantly after the intervention from 21.8 at admission to 67.7 at discharge (Table 1). The median score also increased from 18 at admission to 80 at discharge. Additionally, the score with a narrow range between 18 and 56 at admission had widened to 20 and 115 at discharge (Fig. 2). The paired sample t-test indicated that the FIM score increase was statistically significant (P = 0.0001*). Because the difference between the admission and discharge FIM scores did not follow the normal distribution, we tested the median FIM score differences by a nonparametric related sample Sign test and observed the change to be statistically significant (P = 0.000).

LOS

This study’s main outcome variable was LOS. For the control group, the mean ± SD of LOS was 108 ± 15 days, and the median (IQR) was 94 (66–142) days. In comparison, the average LOS for the experimental group was 61 ± 14 days, with a median (IQR) of 40 (30–86) days. Based on independent-sample Mann–Whitney U test results, the decrease in the experimental group’s LOS was statistically significant (P = 0.01; Fig. 3). Finally, because the positive correlation (Spearman Rho = 0.103, P = 0.716) between the experimental group’s FIM score increase and LOS was statistically insignificant, we could not use Regression to predict patients’ LOS from their FIM score.

Discussion

This study’s early OT intervention was designed to improve TBI patients’ physical, functional, and cognitive status and reduce the complications they experienced from being bedridden and immobile during the ICU stage. In this study, there are many clinical implications which facilitate the intervention as the early intervention itself allows to provide the OT intervention at early stage of injury, the assessment form which includes many scales especially the FIM score, daily documentation, follow-up, and tracking the patients after transferee from the ICU, provide advanced and modern assistive devices and tools to ease patients ADL. The experimental group patients had a much shorter LOS (average 61.53 days) than did the control group (mean 108.86 days). These findings suggest that providing an OT intervention at the early stage of injury can significantly reduce patients’ LOS and consequently help lower their care costs. Additionally, experimental group patients have significant FIM score that increases from admission to discharge.

Generally, few studies have been conducted to elucidate the relationship between the provision of OT for TBI patients in the ICU and LOS, in the middle east or worldwide. For this reason, we considered this study necessary to illustrate the role OT can play in improving patients’ physical and cognitive abilities and reducing their LOS.

A local retrospective study conducted with TBI patients (from acute care and other settings) at a KFMC rehabilitation center between 2009 and 2014 showed an average LOS in the rehabilitation of 64 ± 43 days [5]. Similarly, our experimental group had an average LOS of 61 days, which is within the range of local rehabilitation LOS averages. Similarly, a study by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation reported an average rehabilitation LOS of 22.63 ± 11.68 days, with a range of 4–58 days. These findings indicated a positive correlation between rehabilitation admission and LOS, and the resulting cost of treatment [8]. We observed 61.5 ± 54.2 days of rehabilitation LOS among OT intervention and 108.8 ± 58.1 days among the control group, which was different from the above-mentioned studies.

Although this study’s main goal was not to investigate the functional outcomes of early OT intervention, FIM scores were collected as a secondary factor. The results showed that the experimental group patients’ FIM scores improved significantly by discharge. It is noteworthy that there are many factors contributing this improvement in FIM; the essential factor was the early intervention itself which facilitate the implementation of therapeutic plan early, on the other hand, not only the early intervention, but also the occupational therapist experiences in treating patients at this stage of injury, moreover the awareness and orientations to the nurses, primary teams, and patient’s family about OT interventions; furthermore, some occupational therapists notice that the morning session’s time illustrate high patient’s performance during the sessions. Also patients with family care giver indicate high self-esteem and psychosocial support. Although a related study supported the positive effect of early rehabilitation services on TBI patients’ FIM scores, it also suggested that in some cases, the FIM scale was not sensitive enough to show clinically meaningful improvement [5]. Another study also found positive functional outcomes among severe brain injury patients who received intensive and continuous rehabilitation services [9]. In summary, the literature shows an obvious relationship between rehabilitation in general and shorter LOS for TBI patients worldwide. When comparing our results with those of the local retrospective study, we found that our LOS was similar to that of other local rehabilitation hospitals for TBI, with both groups of patients having good functional outcomes.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the records for control group patients (those admitted and discharged before 2018) were paper-based, as there was no computerized system for patient records at that time. Noncomputerized data collection may result in more errors. Second, the LOS increased for some experimental group patients due to medical complications (e.g., infection) that developed during their hospital stay. Finally, the study’s sample size was small, partly due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Although several studies have shown the importance of rehabilitation interventions for TBI patients, few have focused on the effects of early rehabilitation intervention in general or an early OT intervention specifically. This novel study, implemented with TBI patients in Saudi Arabia, described the importance of early OT intervention—especially during the ICU phase of medical intervention—in reducing LOS. This inquiry was significant, as most medical facilities are concerned about reducing LOS for all patients. Although these results showed a significant effect of early OT intervention in reducing LOS in TBI patients, further study is needed to consider the combined effects of all types of rehabilitation services on this population.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and/or analyzed during the current study is available in the Occupational Therapy Department, as well as in the King Saud Medical City (KSMC) Medisys repository. The research dataset cannot be provided to the third part as per the KSMC Research Data Policy.

References

Get the facts about TBI. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/basics.html. Accessed 01 Oct 2018

Thurman DJ, Alverson C, Dunn KA et al (1999) Traumatic brain injury in the United States: a public health perspective. J Head Trauma Rehabil 14(6):602–615

Neurotrauma J (2012) The changing landscape of traumatic brain injury research. Lancet Neurol 29:32–46

Arabi YM, Haddad S, Tamim HM et al (2010) Mortality reduction after implementing a clinical practice guidelines-based management protocol for severe traumatic brain injury. J Crit Care 25(2):190–195

Arango-Lasprilla JC, Ketchum JM, Cifu D et al (2010) Predictors of extended rehabilitation length of stay after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 91(10):1495–1504

Cowen TD, Meythaler JM, DeVivo MJ et al (1995) Influence of early variables in traumatic brain injury on functional independence measure scores and rehabilitation length of stay and charges. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 76(9):797–803

Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Quear T et al (2004) Significance of poor patient participation in physical and occupational therapy for functional outcome and length of stay. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 85(10):1599–1601

Kunik CL, Flowers L, Kazanjian T (2006) Time to rehabilitation admission and associated outcomes for patients with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 87(12):1590–1596

Andelic N, Bautz-Holter E, Ronning P et al (2012) Does an early onset and continuous chain of rehabilitation improve the long-term functional outcome of patients with severe traumatic brain injury? J Neurotrauma 29(1):66–74

Lipper-Grüner M, Wedekind CH, Klug N (2002) Functional and psychosocial outcome one year after severe traumatic brain injury and early-onset rehabilitation therapy. J Rehabil Med 34(5):211–214

Griesbach GS, Kreber LA, Harrington D, Ashley MJ (2015) Post-acute traumatic brain injury rehabilitation: effects on outcome measures and life care costs. J Neurotrauma 32(10):704–711

Wagner AK, Fabio T, Zafonte RD et al (2003) Physical medicine and rehabilitation consultation: relationships with acute functional outcome, length of stay, and discharge planning after traumatic brain injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 82(7):526–536

Cope DN, Hall K (1982) Head injury rehabilitation: benefit of early intervention. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 63(9):433–437

Qannam H, Mahmoud H, Mortenson WB (2017) Traumatic brain injury rehabilitation in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: time to rehabilitation admission, length of stay and functional outcome. Brain Inj 31(5):702–708

Whyte J, Nordenbo AM, Kalmar K et al (2013) Medical complications during inpatient rehabilitation among patients with traumatic disorders of consciousness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 94(10):1877–1883

Petridou ET, Antonopoulos CN (2017) In International encyclopedia of public health. 2nd ed

Teasdale G, Jennett B (1974) Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: A practical scale. Lancet 2(7872):81–84

Mena JH, Sanchez AI, Rubiano AM et al (2011) Effect of the modified Glasgow Coma Scale score criteria for mild traumatic brain injury on mortality prediction: comparing classic and modified Glasgow Coma Scale score model scores of 13. J Trauma 71(5):1185–1192; discussion 1193

Chehata VJ, Cristian A (2019) In Central nervous system cancer rehabilitation

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Mr. Omar Ibrahim Alkhawaldeh, Mr. Wajih Obaid, Mr. Muflih Alshahrani, Mr. Abdulelah Alnawfal, Ms. Roaa Alobidan, Ms. Alaa Alorf, Ms. Norah Alateeq, and Dr. Parameaswari Parthasarathy Jaganathan. The draft of the manuscript was written by all authors and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the requisite Institutional Review Board (IRB Registration Number with KACST, KSA: H-01-R-053). The confidentiality of the data was maintained according to national bioethics rules and regulations.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The participants have consented to the submission of their data to the journal.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Alkhawaldeh, O.I., Obaid, W., Alshahrani, M. et al. Effect of an early occupational therapy intervention on length of stay in moderate and severe traumatic brain injury patients. Ir J Med Sci 192, 1895–1901 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03226-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03226-0