Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this systematic review is to better understand access to, acceptance of and adherence to cancer prehabilitation.

Methods

MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsychINFO, Embase, Physiotherapy Evidence Database, ProQuest Medical Library, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and grey literature were systematically searched for quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies published in English between January 2017 and June 2023. Screening, data extraction and critical appraisal were conducted by two reviewers independently using Covidence™ systematic review software. Data were analysed and synthesised thematically to address the question ‘What do we know about access, acceptance and adherence to cancer prehabilitation, particularly among socially deprived and minority ethnic groups?’

The protocol is published on PROSPERO CRD42023403776

Results

Searches identified 11,715 records, and 56 studies of variable methodological quality were included: 32 quantitative, 15 qualitative and nine mixed-methods. Analysis identified facilitators and barriers at individual and structural levels, and with interpersonal connections important for prehabilitation access, acceptance and adherence. No study reported analysis of facilitators and barriers to prehabilitation specific to people from ethnic minority communities. One study described health literacy as a barrier to access for people from socioeconomically deprived communities.

Conclusions

There is limited empirical research of barriers and facilitators to inform improvement in equity of access to cancer prehabilitation.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

To enhance the inclusivity of cancer prehabilitation, adjustments may be needed to accommodate individual characteristics and attention given to structural factors, such as staff training. Interpersonal connections are proposed as a fundamental ingredient for successful prehabilitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prehabilitation is a core component of supportive care for health and well-being during cancer survivorship. It aims to improve cancer treatment outcomes and long-term health by preparing people awaiting cancer treatments, not only surgery, through support for physical activity, nutrition and emotional well-being either alone or in combination, and from the point of diagnosis [1]. Growing international evidence indicates that, in specific cancers, engagement with either uni or multimodal prehabilitation interventions can improve individuals’ pre-treatment functional capacity [2, 3], reduce treatment-related complications [4,5,6], ease anxiety [7] and enhance post-treatment recovery [8, 9]. As the evidence base develops and momentum for prehabilitation grows, the need to embed prehabilitation as the standard of care across different cancers has been recognised [10,11,12]. In some regions, multimodal prehabilitation is now offered as the standard of care in certain cancers, particularly lung [13] and colorectal [14].

Internationally, there are persistent health disparities following cancer treatment. Treatment and survival outcomes are poor among people from socioeconomically deprived communities and some minority ethnic groups compared to socioeconomically advantaged and majority groups [15,16,17]. To ease the overall social and economic impact of cancer on individuals and society, and to reduce the societal and healthcare costs of suboptimal treatment outcomes, it is important to identify the facilitators of and barriers to individuals’ engagement with interventions. People from socioeconomically deprived communities and some minority ethnic groups are known to be underserved in prehabilitation interventions [1, 18]. Accordingly, to better understand reasons for informed action, this mixed-methods systematic review aims to identify, critically appraise and synthesise international empirical evidence of the facilitators of and barriers to access, acceptance and adherence of cancer prehabilitation. For this review, prehabilitation is defined as proactive and preventative for all cancer treatments (not only surgery and including neoadjuvant) and includes interventions to support physical activity, nutritional intake or psychological well-being, alone or together, carried out at any time before a course of treatment begins.

Review question

What is known about access, acceptance and adherence to cancer prehabilitation, particularly among socially deprived and minority ethnic groups?

Methods

The systematic review was informed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) mixed-methods systematic reviews (MMSR) methodology [19]. A convergent, integrated approach to data synthesis and integration was adopted [19, 20]. The review was registered in PROSPERO CRD42023403776) on 3 March 2023 and is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [21]. Ethical approval was not required.

Database searches

In collaboration with a specialist health service systematic review librarian, the search strategy was developed using medical subject headings (MeSH) and keywords including and relating to cancer, prehabilitation, inequity, inequality, socioeconomic deprivation, ethnic groups and health services accessibility, and then tested and refined. The electronic databases Ovid SP MEDLINE, CINAHL via EBSCO host, PsycINFO, Ovid SP EMBASE, Ovid Emcare, Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED), Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDRo) and Cochrane Central were systematically searched by EG for studies published in English between January 2017 and May 2023. The search strategy was tailored for each database and detailed in online resource (Supplementary information 1). Supplementary searches of grey literature using the Overton, Dimensions and Proquest dissertation and theses databases (PQDT), and relevant organisational websites were conducted. Reference lists of papers retrieved for full review were scrutinised for potentially useful papers not identified through the database searches.

Selection criteria

The PICO framework was used to guide inclusion criteria on population (P), Intervention (I), comparators (C) and outcomes (O) and context (Co). It enabled identification of primary qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods research studies about prehabilitation, published in peer-reviewed journals. Eligibility criteria were used during study selection to screen this body of literature for empirical data about barriers and facilitators of prehabilitation. Non-empirical, opinion pieces, theoretical and methodological articles, reviews and editorials were excluded, as were studies involving children, adolescents and focusing on end-of-life care.

Study selection

All search results were stored in Endnote™. Following deduplication, results were imported into Covidence™ systematic review management software. For study selection, standardised systematic review methods [22] were used. All project team members were involved in study screening and selection. Firstly, two reviewers independently screened all returned titles and abstracts. Based on eligibility and relevance, these were sifted into ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘maybe’ categories. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. Where a definite decision could not be made, full text was retrieved and assessed. Secondly, full text of all potentially relevant abstracts was retrieved and independently assessed for inclusion by two reviewers against the eligibility criteria. Arbitration by an independent reviewer in the event of disagreement was not required at this stage. Reasons for exclusion at full text review were recorded.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of included studies via Covidence ™ using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 18 [23]. The MMAT was constructed specifically for quality appraisal in mixed studies reviews and is widely used [23, 24]. Within a single tool, Version 18 of the MMAT can be used to appraise the methodological quality of five broad categories of study design, namely qualitative, randomised controlled trials, non-randomised, quantitative descriptive and mixed methods studies. The MMAT comprises two screening questions to establish whether or not the quality appraisal should proceed and 25 core questions: five criteria which mostly relate to the appropriateness of study design and approaches to sampling, data collection and analysis relevant to each of the five study designs [23]. Each criterion is assessed as being met (Yes) or not (No). There is also scope to indicate uncertainty. A third reviewer independently moderated all quality assessments for accuracy.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data systematically via Covidence™ using an adapted, piloted JBI mixed-methods data extraction form. Information extracted included study author, aim, year and country of publication, setting, intervention type, design, sample, data collection, analysis, data relating to prehabilitation facilitators and barriers and, as relevant, data on intervention for support of access, acceptance or adherence to prehabilitation. A third reviewer cross-checked the data extraction tables independently for accuracy and completeness.

Data synthesis and integration

All extracted findings were imported into Microsoft Excel. Quantitative data were ‘qualitised’ into textual descriptions of quantitative results to enable assimilation with qualitative data [25]. To analyse and synthesise all findings, thematic synthesis [26, 27] was used. Thematic analysis is an established process involving the identification and development of patterns and analytic themes in primary research data. Two reviewers coded the findings and then grouped related codes into preliminary descriptive themes which captured patterns across the data describing barriers to and facilitators of cancer prehabilitation [26]. Preliminary themes were discussed with a third reviewer. Themes were then further combined and synthesised to generate three overarching analytical themes relative to the review question [26].

Results

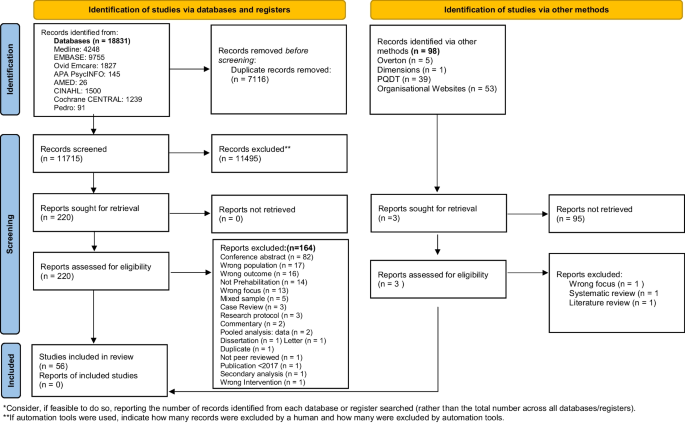

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow chart of search results. Following the first and second round screening, 56 papers published between 2017 and 2023 were included: 33 quantitative; 14 qualitative and nine mixed methods.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources. *Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). **If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

A synopsis of study characteristics and the quality appraisal outcomes is found in Table 1. Brief narrative summaries of the included papers’ findings of relevance to the review question, namely access, acceptance and adherence of prehabilitation interventions, are provided in the online supplementary information (supplementary information 2).

Study characteristics

Of the 32 quantitative studies reviewed, there were eight randomised controlled trials, two single-arm multi-centre trials, seven cohort studies and one cross-sectional survey. Others were pilot (n = 3), feasibility (n = 7), observational (n = 1) and prevalence (n = 1) studies, with one non-randomised trial and one audit. Qualitative studies (n = 15) mainly used a broad qualitative approach (n = 12), one used phenomenology, one participatory action research and one used a cross-sectional survey. Nine studies used mixed methods.

Study populations

The majority of included studies were conducted in Europe (n = 33) (UK (n = 19), Netherlands (n = 4), Denmark (n = 3), Spain (n = 1), France (n =1), Portugal (n = 1), Belgium (n = 1), Slovenia (n = 1), Norway (n = 1) and Sweden (n = 1)). Eleven were conducted in North America (Canada (n = 8), United States (n =3)), and eight were from Australia. The remaining studies were from Japan (n = 1) and China (n =1), and two studies were conducted across two countries, Australia and New Zealand and the UK and Norway. Studies focused on prehabilitation in different settings including hospitals (n = 12), local communities (including universities and local gymnasiums), individuals’ homes (n = 14) and outdoors (n = 1). Ten studies reported a hybrid, home and hospital approach to prehabilitation, whilst digital prehabilitation was reported in nine studies. Fifty-three studies were conducted in a range of cancers. Of these, 41 reported data for a single cancer site: colorectal (n = 11); gastrointestinal (n = 9); lung (n = 7); haematology (n=4); breast (n = 3); head and neck (n =2); bladder (n = 2) prostate (n=1) and a range of abdominal surgeries (n = 3). In 12 studies, cancer sites were pooled. Three studies focused on healthcare professionals (n = 2) and key stakeholders (n = 1).

Methodological quality

There was considerable variation in the methodological quality of the 56 studies included. Twelve studies, 10 qualitative and two quantitative, satisfied all the MMAT criteria [23]. Fourteen studies, nine mixed methods, two qualitative and three quantitative, satisfied just one or two criteria. Thus, data were extracted from a body of literature where one-fifth (21%) of publications were about research of the highest quality, defined as having met 100% of the MMAT criteria [23]. Detailed results of the MMAT quality assessments are found in supplementary information (supplementary information 3).

Thematic synthesis

The thematic synthesis identified three cross-cutting analytic themes. As illustrated in Figure 2, these themes reflected individual, structural and interpersonal facilitators of and barriers to access, acceptability and adherence of cancer prehabilitation:

Theme 1 The influence of individual drivers of cancer prehabilitation engagement

Theme 2 Providing acceptable cancer prehabilitation service and interventions

Theme 3 Interpersonal support – the unifying golden thread

Interpersonal support was the unifying golden thread as it facilitated the fit between the individual and the structural for access to, acceptance of and adherence to prehabilitation.

Theme 1. The influence of individual drivers of cancer prehabilitation engagement

Factors at the level of the individual were found to shape prehabilitation access, acceptance and adherence. These included perceived need and benefits, motivations, health status and everyday practicalities.

The perceived need for and potential benefits of prehabilitation

A key stimulus for accessing and adhering to cancer prehabilitation was a belief that engagement might confer benefit. Influences included clinicians’ prehabilitation endorsement and encouragement [12, 13, 42, 52, 55, 59, 60, 65, 66, 71], positive prior personal experiences of routine physical activities [60, 69, 70, 77] and weight loss programmes [77], other patients’ support [12, 71] and the perceived need to improve personal fitness [60, 63]. Some participants in UK-based studies believed they had a social responsibility to engage in prehabilitation [63, 64] as enhanced fitness would benefit healthcare services financially [12, 64].

The money, the cost per night in the hospital, goodness knows how much that costs and the follow-up with all the doctors, the dieticians and everyone else behind (….). It’s (prehabilitation) saving the NHS thousands and thousands of pounds of money ([64] p.4).

Several studies indicated some individuals perceived prehabilitation to be beneficial in that interventions provided a welcome distraction from their illness and situation [64, 72, 74]. Benefit was understood in terms of being psychologically and physically prepared for cancer treatments, potentially enhancing post-treatment recovery and survival [12, 55, 60, 63, 64, 66,67,68, 70, 71, 74].

I benefited a lot from it because it caught me in that time just after diagnosis when things were pretty scary and pretty awful and I felt like it was one of the key pieces of my plan for positivity during this whole thing, because it was setting a tone for recovery ([74] p. 8)

Yet, it was also clear that some individuals were disinterested in engaging with prehabilitation [56, 58, 66, 74, 80]. Some studies suggested a connection between imminent surgery and patients’ perceptions of little benefit of prehabilitation in the short timescales [47, 54, 63, 69, 77, 79]. Some individuals felt that making additional hospital visits for prehabilitation was onerous [54]. Others were unaccustomed to or did not want to exercise [36, 70] or perceived exercise as demanding [41], particularly when combined with cancer treatment [51]. Some considered their existing fitness levels [61, 63] and diet [61] sufficient. A sense of low perceived benefit of or need for prehabilitation meant it was considered a low priority [36].

Personal motivators

A cancer diagnosis [71, 77] conjoined with the desire to improve fitness [63, 64, 72], survive surgery [63, 64] and to be present for and enjoy their families [64] were influential motivators for individuals’ proactively effecting lifestyle change and thus engagement with prehabilitation. Having accessed prehabilitation, exercise logs and diaries [64, 68, 74], personal goal setting [61, 64, 71], progress self-monitoring [61, 64, 68, 71, 77], activity tracking and objective feedback [56, 60] motivated individuals to maintain participation. They inspired them to remain on track, enabled them to realise their progress, build self-efficacy for prehabilitation adherence [60, 70, 73, 76, 77] and, through a process of cognitive reframing, regain a sense of control [71].

Now I have a feeling of control over my body . . . I don’t want cancer to define me. [71]

Nonetheless, one study reported that motivation to access prehabilitation may be negatively affected by low levels of health literacy, which is associated with socioeconomic deprivation [46]. Furthermore, sustaining motivation to continue prehabilitation could be challenging [43, 45, 58, 64, 70, 74], especially when faced with unanticipated setbacks such as delayed surgery [57] or insufficient peer support [64].

The enduring problems of health limitations

Individuals’ physical and psychological health status influenced prehabilitation access and adherence, particularly when there was a perception of insufficient on-going professional [61, 72, 73] and family support [31], and interventions were located away from home. Pancreatic cancer [33] adversely affected individuals’ access to prehabilitation. Furthermore, physical health problems limited some individuals’ ability to travel and thus access hospital-based prehabilitation [54, 59, 71]. Symptoms experienced and perceived health status influenced individuals’ prehabilitation adherence. Reported adherence barriers included physical symptoms [61, 67, 70, 72, 73, 81] such as fatigue [45, 50, 57, 70, 73], pain [40, 45, 57, 59, 70, 71, 73], digestive problems [30, 35, 39, 47, 55, 67] and feeling unwell [40, 43, 64, 79]. In addition, functional limitations [63, 70] associated with comorbidities [31, 37, 40, 49, 51, 57, 64, 70, 77], disease status [37, 41], pre-surgery neoadjuvant treatments [37, 53, 64, 70, 81] and mental health problems [35, 39] were all reported to negatively affect individuals’ ability to engage with and adhere to prehabilitation, particularly in terms of physical activities.

Several studies reported that psychological distress had a negative effect on prehabilitation access and adherence [59, 61, 70, 73]. Described by a participant in one study [63] as ‘dark moments’, as anxiety and stress were often connected with attending hospitals [71]. In addition, several studies reported that individuals felt overwhelmed, both generally [42, 57, 74] and emotionally [12, 70], in advance of their treatments. Information overload [62] and competing personal matters which required their attention pre-treatment [70, 80] contributed to the sense of feeling overwhelmed.

The challenges of everyday life

Across studies, insufficient time for prehabilitation was frequently reported [40, 50, 51, 55, 58, 66, 71, 72, 74, 77, 78]. Some individuals described competing priorities in the short space of time between diagnosis and treatment [49, 57, 59, 70, 79]. This was partly due to putting affairs in order, prioritising family time [61] or treatments being scheduled earlier than originally planned [35, 54, 55]. Others were constrained by their employment [51, 70, 73, 80] and family responsibilities, including caring for other family members [55, 58, 70]. Additional barriers to prehabilitation engagement included geographical distance to hospitals delivering prehabilitation [28, 32, 41, 51, 54, 57, 63, 74]; transport difficulties [29, 49, 51, 54, 58, 60, 66, 79] and associated financial costs [51, 66, 71]; inclement weather, particularly in relation to prehabilitation with outdoor exercise components [45, 57, 64, 70, 73, 74]; low digital literacy [34, 42, 76]; restricted or limited access to and problems with technology [42, 56, 76, 80], notably broadband [45, 79] and experiencing physical discomfort with exercise equipment [60, 64].

Theme 2. Providing acceptable cancer prehabilitation service and interventions

The prehabilitation environment, mode of delivery (which might be technological) and the perceived utility of interventions were important facilitators of access [34, 48, 57, 66, 71, 75, 80] and adherence [36, 45, 48, 61] and influenced acceptance [36, 52, 61, 64, 69, 71, 77, 80, 81].

The value of home-based prehabilitation

Home-based prehabilitation interventions with remote professional supervision and support were accepted for their convenience [38, 74], capacity to motivate [38, 61, 64, 73] and build self-efficacy [40, 61, 64, 73] and perceived benefit [40, 69, 74]. Specifically, individuals reported that home-based prehabilitation enabled them to integrate interventions into their everyday lives [61, 64]. Exercising in the safe, private, space of home was enjoyable [36, 66], could help with overcoming self-consciousness and engendered a sense of control [61, 64].

I couldn’t go to the gym any longer. I can’t very well be running out to the toilet the whole time. So, I had to find something else, so it was that [static bike at home]. ([61] p. 206)

…I don’t want to do it [prehabilitation] in a hospital because I think it then becomes really competitive. And people are, like, if they can’t do it, they feel…. They would feel like, ‘Oh, I’m not strong enough…’ you know what I mean. It might depress them. Whereas if you do it in the house, you can do it at your own pace, there’s nobody watching over you and everything. [64]

Home-based prehabilitation interventions were important facilitators of access [48, 66] and adherence [36, 48, 61]. The provision of portable exercise equipment such as resistance bands enabled sustained adherence, particularly when individuals were temporarily away from home [74]. Some individuals welcomed the freedom and flexibility of home-based prehabilitation [72]. Yet despite being provided with resources to monitor [34, 42, 52, 64, 66, 76], supplement and continue physical activity at home [48, 63, 66, 74, 77], insufficient in-person healthcare professional engagement and encouragement could mean adherence was often difficult to monitor [69, 81] and sustained intervention adherence could be challenging [28, 63, 64] and afforded a low priority by individuals [61, 72, 73].

There had to be real pressure, there really had! And then if suddenly they were not around (the health professionals), then I’m not sure I’d finish it. That’s how I am. You have to keep an eye on me. [72]

Navigating the technological space of tele-prehabilitation

Sometimes referred to as ‘tele’ or ‘digital’-prehabilitation, technology-based uni and multimodal home-based prehabilitation capitalised on internet and/or telephone communication services and was delivered using smartphones, videos, wearable technology, tablets, mobile applications, video platforms and secure video conferencing [34, 36, 42, 45, 56, 70, 71, 76, 80]. In terms of acceptability, individuals perceived home-based, tele-prehabilitation programmes as accessible, particularly during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic [34, 71, 80]:

Having prehabilitation outside of the hospital setting made things easier. I wasn’t feeling good with the pain and couldn’t travel too far. Could also do it in my own time ([71] p. 646)

Home-based tele-rehabilitation was also perceived as motivating [36, 45, 56, 76], conferred benefit [34, 36, 45, 56, 80], particularly when personalised [34, 45, 56, 71] and reduced transport-associated costs [80].

Sustained tele-prehabilitation engagement was aided by the provision of smartphones [56, 76], tablets with relevant applications and content downloaded [34], training watches [34, 56, 76], supplementary information and alternate web browser pathways for those without access to or with low digital literacy [42] and integrated digital training and support during the intervention’s implementation [34, 36, 42].

I would not have been able to endure the treatments and the surgery thereafter had it not been for the continuous support I was receiving through the digital platform. [34]

Reported barriers were primarily intervention specific. They included technical [45, 80] and device connectivity issues [34, 76], broadband and website interface problems, particularly for individuals unaccustomed to using technology [45]. Negative views of mobile mindfulness apps [56] and equipment aesthetics [76] were also described.

The perceived utility of prehabilitation interventions

Interventions that were perceived as being accessible in terms of their user-friendliness [34, 56, 74, 76] and appropriately designed to meet individuals’ needs, preferences and capabilities in terms of their structure [40, 52, 60, 68, 74, 77, 78], notably coherence [36, 38, 45, 75, 76] and components [38, 54, 55, 64, 69, 74], including nutritional supplements [44, 54, 55, 67], enhanced acceptability. The acceptability of prehabilitation interventions was reflected in the expressions of gratitude [12] and the positive ways in which interventions were variously described by individuals in some studies [12, 38, 58, 64, 74] as ‘excellent’, ‘very good’, ‘great’, ‘brilliant’, ‘hugely beneficial’ and ‘fun’. Some would even recommend home-based prehabilitation to people preparing for cancer treatments [52, 63, 68, 74]. However, one study [42] reported that unfamiliarity with the English language had a negative impact on access, whilst in another study [56], individuals reported adhering to protein targets challenging.

At an individual level, the availability [61] and extent of integrated healthcare professional supervision and support was perceived to enable intervention access [75] and adherence [42, 60, 61, 64, 66, 68, 69, 74, 78], particularly when this was personalised [34, 45, 56, 65, 68, 71, 78]. Unpalatable nutritional interventions had a negative effect on intervention adherence [30, 50], and it was reported that inspiratory muscle training devices could be difficult for individuals to use [38].

Healthcare professionals reported organisational barriers to implementation, and thus individuals’ access to, acceptance of and adherence with prehabilitation. These barriers included workforce capacity limitations [12, 65, 75, 79, 81], including insufficient embedded specialist prehabilitation professionals [69, 81], delayed or insufficient referral to prehabilitation [33, 44, 63], disconnect in cross-boundary systematic service delivery and communication [12, 28, 75, 81], inadequate funding [12, 65, 79, 81] and awareness of local prehabilitation provision, uncertainty regarding what constitutes prehabilitation among some healthcare professionals [28, 79, 81] and space and time constraints [69, 81] together with insufficient equipment [28] in hospital settings to deliver interventions [81].

Theme 3. Interpersonal support: the unifying golden thread

Across the studies reviewed, the unifying golden thread was interpersonal support, for this was an important, valued enabler of prehabilitation access [64] acceptance and adherence. It was reported that interpersonal support was derived from family and friends [12, 45, 60, 61, 64, 70, 73], prehabilitation healthcare professionals [42, 51, 55, 60, 61, 63, 64, 66, 69, 71, 75, 78], prehabilitation peers [51, 59], volunteers [79] and in-person and online peer support groups [71, 79]. When embedded within interventions, a network of interpersonal support helped to sustain prehabilitation adherence, particularly in relation to physical activity [59, 60, 68, 72, 79]. During what could be challenging times, the interpersonal support experienced during prehabilitation enhanced interventions’ acceptability [52, 60, 63, 68].

The active involvement of family during physical activities such as walking and exercise routines was reported to generate a sense of companionship, encouragement and motivational and psychological support [34, 60, 61, 64, 70, 71, 77]. In these ways, prehabilitation interventions with embedded family support enhanced their acceptability [52].

My wife did the same ones with me so there were two of us doing the same stuff. We did the walks together. Then we would both do the exercises. So that was good company. [64]

Findings reported in one study [31] indicated that living alone could have a negative effect on prehabilitation adherence.

The acceptability of prehabilitation interventions was enhanced by relevant healthcare professionals’ supportive dialogue in the shape of information, personalised encouragement, validation and timely, constructive feedback on individuals’ engagement, progress and performance [69, 77], signposting to other support services [63] and broader emotional support [77]. In addition to sustaining prehabilitation behaviours through collaboration, activation and motivational support [60, 61, 71, 72, 77, 78], healthcare professionals’ presence instilled a sense of trust [71], comfort [51] and safety [38, 62, 63] and reduced feelings of social isolation [71]. The need for and importance of supportive dialogue with healthcare professionals during prehabilitation was identified by participants in one study investigating individuals’ experiences of multimodal prehabilitation delivered via a leaflet and with no embedded healthcare professional support [73].

I have only been a number. Like I was a garden shovel with a barcode that you scanned at the cash register. There is no one who thinks about what this means for one’s self-understanding–- just to be regarded as a disease [...] There is no one asking about the human being behind it. It is insane [73]

For some participants, peer support in the shape of information sharing was beneficial and enabled prehabilitation access [63, 71]. Integrated group or one to one peer support was reported to enhance an intervention’s acceptability [12, 63]. In part, this was because individuals did not always want to engage their families, and peer support reduced their sense of isolation [71]. Peer support was reported to be beneficial in terms of interaction with others in a similar situation, thereby lending individuals’ social, emotional and motivational support, enabling them to remain on track with their prehabilitation programme [51, 59, 64, 66, 71].

Exercising in a group motivates. Let new patients exercise with other patients who are further along and have more experience exercising. They (experienced patients) can then tell them, Yes, you will get muscle aches, but they will subside too. [59]

It was clear from some studies that the absence of peer support in prehabilitation interventions was lamented [64, 71], with some participants exercising agency and accessing online patient forums to derive required support [71].

Discussion

This review reports findings from across the globe regarding facilitators of and barriers to access, acceptance and adherence of cancer prehabilitation. The findings draw attention to cross-cutting themes at individual and structural levels and interpersonal factors that connect the levels. As illuminated in Fig. 2, the multifaceted facilitators and barriers underscore the complexity of cancer prehabilitation access, acceptance and adherence.

This review found interpersonal connections, support either directly obtained from peers, family, healthcare professionals or via digital connectivity, can facilitate a fit between the individual factors and structural factors that affect engagement with prehabilitation. Examples include encouragement from a spouse willing to engage in a recommended physical activity with the patient, practical help with digital technology, peer support during group prehabilitation and health professional supervision. Support through these interpersonal connections may be a core ingredient for successful access, acceptance and adherence. This proposition should now be explored and tested. There may be sub-groups with need or preference for certain sources of interpersonal support. Our review was designed to find out ‘what is known about access, acceptance and adherence to cancer prehabilitation, particularly among socially deprived and minority ethnic groups’ because of the known benefits from prehab for post treatment recovery [8, 9]. It found no empirically based analysis of prehabilitation access, acceptance or adherence by people from these groups.

The individual and structural context

This review revealed individual factors enabling or impeding prehabilitation access, acceptance and adherence include personal beliefs and understandings about potential harms or benefits; motivations, for example finding enjoyment in participation; health status and everyday practicalities such as time and transport availability. Structural factors identified included the availability of knowledgeable and supportive health professionals and/or people affected by cancer’ service organisation, such as the availability of a prehabilitation multidisciplinary team and the place and space of service delivery, for example, if it was available in the community.

Individual and structural level factors affecting access to cancer treatment and care are widely reported [82,83,84,85]. Some are proposed to be modifiable for improved health outcomes in groups at risk of poor health because of poverty and/or discrimination based on age, race, ethnicity or gender [84]. The findings of the review are consistent with this wider literature on service access, acceptance and adherence. It is notable that although our search was designed to identify all literature about access, acceptance and adherence to cancer prehabilitation from 2017 to 2023, we found no analysis of structural differences. The differential experience of people from structurally vulnerable groups, for example, those who are socioeconomically deprived or from minority communities, had not been considered. Yet, evidence indicates that cancer rehabilitation services are underutilised by people from socioeconomically deprived communities [86, 87] and ethnic minorities [88]. We also know patient engagement with prehabilitation is variable [89], and third sector organisations claim people from socioeconomically deprived communities, which include people from some ethnic minorities, are underserved by prehabilitation services [1]. Exploration and understanding of difference in prehabilitation experiences across social groups is needed if support for access, acceptance and adherence is to achieve equity in health outcomes.

Interpersonal connections linking individual experience and structural context

This review identified that it was people, namely peers, family members and friends, who, through their support, influenced the extent to which individual and structural level factors were obstacles or enablers of prehabilitation. In the relational space between individual experience and the infrastructure in place to enable prehabilitation, these people were supportive actors, influencing individuals’ access to, acceptance of and adherence to prehabilitation.

International studies have revealed that interpersonal support is related to mental and physical health. Low perceived social support has been shown to be associated with mental and physical health problems [90]. In the USA, a high level of perceived social support was found more likely in women and young people and low level of perceived social support more likely for those living in poverty [90]. Loneliness has been proposed the mediating factor between socioeconomic status and health in a Norwegian population-based study of people aged over 40 years [91]. Two explanations were suggested. Firstly, people with few social contacts have low levels of physical activity. Secondly, people with poor physical or emotional health are more likely to have low self-esteem and self-efficacy in self-care, which is associated with less successful occupational career and low socioeconomic status and thus fewer social contact resources to manage health [91].

This review supports an argument that interpersonal connections can be important for prehabilitation access, acceptance and adherence. It found evidence of relationships with family, peers and cancer care staff influencing access to, acceptance of, and adherence to prehabilitation. Perceived social support may have a key role in successful prehabilitation. This proposition should be further explored, paying attention to the known relationship between social support and socioeconomic status in other contexts and the potential for this to be an explanation of any observed difference in access across socioeconomic groups.

Technology as interpersonal connection?

An interesting finding is of data showing some people find web-based resources and/or online help to satisfy their prehabilitation information and support needs. These people experienced interpersonal connection through technology. An online survey among 1037 adults (18+) in the UK found that 80% of those with a long-term condition used technology for managing their health, a majority for seeking information whilst a third used wearable technology or apps. Those most likely to use technologies were younger and/or of high socioeconomic status, leading the authors to caution completely digital approaches because of the potential to exclude some groups from the care they need [92]. Arguably, technology may provide a partial solution to enabling successful prehabilitation.

What this review adds

Our finding of structural and individual level factors affecting access to, acceptance of and adherence to prehabilitation is consistent with Levesque et al.’s [93] socioecological model of access to health services. Levesque et al.’s [93] model sets out access as a process with five dimensions of accessibility (approachability; acceptability; availability and accommodation; affordability; appropriateness) and five corresponding abilities of populations (ability to perceive; ability to seek; ability to reach; ability to pay; ability to engage). The model enables attention to social, service organisation and person-centred factors that influence access. However, the model does not address the relational dimensions derived from our data analysis, i.e. how person-centred and structural factors interrelate for better or poorer service access. Based on our findings, an important ingredient for improving access to prehabilitation may be attention to what happens in the relational space connecting these factors. Voorhees et al. [94] interpreted findings of participatory research about access to general practice and claimed it is the human abilities of workforce and clients that are an important yet absent consideration in Levesque’s model. They argued that staff training and support for human interaction were needed. We agree. In addition, and based on our analysis, we also consider important the network of interactions between patient and others. Understanding the nature and mechanisms of these interactions may be important for health equity in prehabilitation.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this review is that established, rigorous systematic review processes were followed to identify and select relevant peer-reviewed literature. Methods and thematic synthesis procedures were reported explicitly, providing an audit trail for dependability. To maximise study identification, the detailed and comprehensive search strategy was developed with the assistance of an expert information specialist, and the review was conducted by a multidisciplinary team with a minimum of two reviewers engaged in the screening and extracting process. Searches were limited from 2017 to 2023 and published in the English language. By limiting the search dates in this way, we have ensured that the evidence assessed has context and relevance to current policy and practices. This systematic review, as a result, provides an overarching picture and holistic understanding of access, acceptance and adherence to cancer prehabilitation. However, this review is not without its limitations. It is possible that some potentially useful studies, notably those not published in the English language have been omitted. Furthermore, we did not take account of study quality in our analysis. To reduce the risk of selection bias, studies were included irrespective of their methodological quality assessment. However, this means that some low quality evidence has been included, and this is a limitation to the credibility of the analysis. Nevertheless, there is some consistency between studies and across international healthcare settings. This does indicate a level of trustworthiness in the review findings. The review was of mixed cancer sites. Cancer site along with its symptoms and treatment-related problems may affect access, acceptance and adherence to prehabilitation. As the body of literature about engagement with prehabilitation grows, further work will be warranted to investigate cancer site–specific factors affecting inclusion in prehabilitation.

Conclusion

ThQueryere is limited empirical study of barriers and facilitators to inform improvement in equity of access to cancer prehabilitation. To enhance the inclusivity of cancer prehabilitation, adjustments may be needed to accommodate individual preferences and characteristics, such as comorbidity, and attention given to structural factors, such as staff training. Based on our findings, we propose interpersonal connections as a fundamental core ingredient for facilitation of prehabilitation access, acceptance and adherence.

Systematic review registration

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023403776)

Data Availability

All data generated for this review are included in the manuscript and/or the supplementary files.

References

Macmillan Cancer Support. Prehabilitation for people with cancer: Principles and guidance for prehabilitation within the management and support of people with cancer. Macmillan Cancer Support. 2020. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/news-and-resources/guides/principles-and-guidance-forprehabilitation. Accessed 03 Mar 2023.

Waterland JL, McCourt O, Edbrooke L, Granger CL, Ismail H, Riedel B, Denehy L. Efficacy of prehabilitation including exercise on postoperative outcomes following abdominal cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis Front Surg. 2021;19(8):628848. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2021.628848.

Falz R, Bischoff C, Thieme R, Lässing J, Mehdorn M, Stelzner S, Busse M, Gockel I. Effects and duration of exercise-based prehabilitation in surgical therapy of colon and rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022;148(9):2187–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-04088-w.

Moran J, Guinan E, McCormick P, Larkin J, Mockler D, Hussey J, Moriarty J, Wilson F. The ability of prehabilitation to influence postoperative outcome after intra-abdominal operation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery. 2016;160(5):1189–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2016.05.014.

Halliday LJ, Doganay E, Wynter-Blyth VA, Hanna GB, Moorthy K. The impact of prehabilitation on post-operative outcomes in oesophageal cancer surgery: a propensity score matched comparison. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25(11):2733–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04881-3.

Heil TC, Verdaasdonk EGG, Maas HAAM, van Munster BC, Rikkert MGMO, de Wilt JHW, Melis RJF. Improved postoperative outcomes after prehabilitation for colorectal cancer surgery in older patients: an emulated target trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30(1):244–54. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-12623-9.

Scriney A, Russell A, Loughney L, Gallagher P, Boran L. The impact of prehabilitation interventions on affective and functional outcomes for young to midlife adult cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2022;31(12):2050–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.6029.

Michael CM, Lehrer EJ, Schmitz KH, Zaorsky NG. Prehabilitation exercise therapy for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2021;10(13):4195–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.4021.

Minnella EM, Awasthi R, Bousquet-Dion G, Ferreira V, Austin B, Audi C, Tanguay S, Aprikian A, Carli F, Kassouf W. Multimodal prehabilitation to enhance functional capacity following radical cystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7(1):132–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2019.05.016.

Stout NL, Silver JK, Baima J, Knowlton SE, Hu X. Prehabilitation: an emerging standard in exercise Oncology. In: Schmitz K, editor. Exercise Oncology. Switzerland AG: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 111–43.

Moore J, Merchant Z, Rowlinson K, McEwan K, Evison M, Faulkner G, Sultan J, McPhee JS, Steele J. Implementing a system-wide cancer prehabilitation programme: the journey of Greater Manchester's Prehab4cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021; 47(3 Pt A):524-532 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2020.04.042

Bingham SL, Small S, Sempl CJ. A qualitative evaluation of a multi-modal cancer prehabilitation programme for colorectal, head and neck and lung cancer patients. PLoS One. 2023;18(10):e0277589. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277589.

Bradley P, Marchant Z, Rowlinson-Groves K, Taylor M, Moore J, Evison M. Feasibility and outcomes of a real-world regional lung prehabilitation programme in the UK. Br J Anaesth. 2023;130(1):e47-e55 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2022.05.034

Sabajo CR, Ten Cate DWG, Heijmans MHM, Koot CTG, van Leeuwen LVL, Slooter GD. Prehabilitation in colorectal cancer surgery improves outcome and reduces hospital costs. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2024;50(1):107302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2023.107302.

Ammitzbøll G, Levinsen AKG, Kjær TK, Ebbestad FE, Horsbøl TA, Saltbæk L, Badre-Esfahani SK, Joensen A, Kjeldsted E, Halgren Olsen M, Dalton SO. Socioeconomic inequality in cancer in the Nordic countries. A systematic review. Acta Oncol. 2022;61(11):1317–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2022.2143278.

Boujibar F, Bonnevie T, Debeaumont D, Bubenheim M, Cuvellier A, Peillon C, Gravier FE, Baste JM. Impact of prehabilitation on morbidity and mortality after pulmonary lobectomy by minimally invasive surgery: a cohort study. J Thorac Dis. 2018; 10(4):2240-2248. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2018.03.161

Giaquinto AN, Miller KD, Tossas KY, Winn RA, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African American/Black People. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(3):202-229. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21718

Lee D, Wang A, Augustin B, Buajitti E, Tahasildar B, Carli F, Gillis C. Socioeconomic status influences participation in cancer prehabilitation and preparation for surgical recovery: a pooled retrospective analysis using a validated area-level socioeconomic status metric. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2023;49(2):512–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2022.10.023.

Lizorando L, Stern C, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, Apostolo J, Kirkpatrick P, Loveday H (2020) Mixed methods systematic reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI. 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-09

Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, Wassef M. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;29(372):n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Centre for Reviews & Dissemination. CRD’s guidance on undertaking reviews in health care. York: University of York; 2009.

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, O’Cathain A, Rousseau MC, Vedel I, Pluye P. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information. 2018;34:285–91. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221.

Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, Macaulay AC, Salsberg J, Jagosh J, Seller R. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002.

Stern C, Lizarondo L, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, Apóstolo J, Kirkpatrick P, Loveday H. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2108–18.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

Thomas J, O’Mara-Eves A, Harden A, Newman M. Synthesis methods for combining and configuring textual or mixed methods data. In: Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J, editors. An introduction to systematic reviews. London: Sage Publishing; 2017. p. 181–209.

PREPARE-ABC Trial Collaborative SupPoRtive Exercise Programmes for Accelerating REcovery after major ABdominal Cancer surgery trial (PREPARE-ABC). Pilot phase of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23(11):3008-3022. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15856

Argudo N, Rodó-Pin A, Martínez-Llorens J, Marco E, Visa L, Messaggi-Sartor M, Balañá-Corberó A, Ramón JM, Rodríguez-Chiaradía DA, Grande L, Pera M. Feasibility, tolerability, and effects of exercise-based prehabilitation after neoadjuvant therapy in esophagogastric cancer patients undergoing surgery: an interventional pilot study. Dis Esophagus. 2021; 34(4):doaa086. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doaa086

Burden ST, Gibson DJ, Lal S, Hill J, Pilling M, Soop M, Ramesh A, Todd C. Pre-operative oral nutritional supplementation with dietary advice versus dietary advice alone in weight-losing patients with colorectal cancer: single-blind randomized controlled trial. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8(3):437–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12170.

Catho H, Guigard S, Toffart AC, Frey G, Chollier T, Brichon PY, Roux JF, Sakhri L, Bertrand D, Aguirre C, Gorain S, Wuyam B, Arbib F, Borel JC. What are the barriers to the completion of a home-based rehabilitation programme for patients awaiting surgery for lung cancer: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e041907. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041907.

Crowe J, Francis JJ, Edbrooke L, Loeliger J, Joyce T, Prickett C, Martin A, Khot A, Denehy L; Centre for Prehabilitation Peri-operative Care (CPPOC). Impact of an allied health prehabilitation service for haematologic patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy in a large cancer centre. Support Care Cancer. 2022; 30(2):1841-1852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06607-w

Deftereos I, Yeung JM, Arslan J, Carter VM, Isenring E, Kiss N, On Behalf Of The Nourish Point Prevalence Study Group. Preoperative nutrition intervention in patients undergoing resection for upper gastrointestinal cancer: results from the Multi-Centre NOURISH Point Prevalence Study Nutrients. 2021;13(9):3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093205

Drummond K, Lambert G, Tahasildar B, Carli F. Successes and challenges of implementing teleprehabilitation for onco-surgical candidates and patients’ experience: a retrospective pilot-cohort study. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):6775. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10810-y.

Ferreira V, Lawson C, Carli F, Scheede-Bergdahl C, Chevalier S. Feasibility of a novel mixed-nutrient supplement in a multimodal prehabilitation intervention for lung cancer patients awaiting surgery: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Int J Surg. 2021;93:106079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106079.

Franssen RFW, Bongers BC, Vogelaar FJ, Janssen-Heijnen MLG. Feasibility of a tele-prehabilitation program in high-risk patients with colon or rectal cancer undergoing elective surgery: a feasibility study. Perioper Med (Lond). 2022;11(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-022-00260-5.

Halliday LJ, Doganay E, Wynter-Blyth V, Osborn H, Buckley J, Moorthy K. Adherence to pre-operative exercise and the response to prehabilitation in oesophageal cancer patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25(4):890–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04561-2.

Karlsson E, Farahnak P, Franzén E, Nygren-Bonnier M, Dronkers J, van Meeteren N, Rydwik E. Feasibility of preoperative supervised home-based exercise in older adults undergoing colorectal cancer surgery - a randomized controlled design. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219158. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219158.

Lawson C, Ferreira V, Carli F, Chevalier S. Effects of multimodal prehabilitation on muscle size, myosteatosis, and dietary intake of surgical patients with lung cancer - a randomized feasibility study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021;46(11):1407–16. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2021-0249.

Machado P, Pimenta S, Garcia AL, Nogueira T, Silva S, Oliveiros B, Martins RA, Cruz J. Home-based preoperative exercise training for lung cancer patients undergoing surgery: a feasibility trial. J Clin Med. 2023;12(8):2971. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12082971.

Minnella EM, Baldini G, Quang ATL, Bessissow A, Spicer J, Carli F. Prehabilitation in thoracic cancer surgery: from research to standard of care. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35(11):3255–64. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2021.02.049.

Moorthy K, Halliday LJ, Noor N, Peters CJ, Wynter-Blyth V, Urch CE. Feasibility of implementation and the impact of a digital prehabilitation service in patients undergoing treatment for oesophago-gastric cancer. Curr Oncol. 2023;30(2):1673–82. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30020128.

Naito T, Mitsunaga S, Miura S, Tatematsu N, Inano T, Mouri T, Tsuji T, Higashiguchi T, Inui A, Okayama T, Yamaguchi T, Morikawa A, Mori N, Takahashi T, Strasser F, Omae K, Mori K, Takayama K. Feasibility of early multimodal interventions for elderly patients with advanced pancreatic and non-small-cell lung cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10(1):73–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12351.

Paynter E, Whelan E, Curnuck C, Dhaliwal S, Sherriff J. Pre-operative immunonutrition therapy in upper gastrointestinal cancer patients: postoperative outcomes and patient acceptance. AMJ. 2017;10(6):466–473. https://doi.org/10.21767/AMJ.2017.2962

Piraux E, Caty G, Reychler G, Forget P, Deswysen Y. Feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of a tele-prehabilitation program in esophagogastric cancer patients. J Clin Med. 2020;9(7):2176. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9072176.

Qin PP, Jin JY, Min S, Wang WJ, Shen YW. Association between health literacy and enhanced recovery after surgery protocol adherence and postoperative outcomes among patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: a prospective cohort study. Anesth Analg. 2022;134(2):330–40. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005829.

Rupnik E, Skerget M, Sever M, Zupan IP, Ogrinec M, Ursic B, Kos N, Cernelc P, Zver S. Feasibility and safety of exercise training and nutritional support prior to haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with haematologic malignancies. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):1142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07637-z.

Santa Mina D, Hilton WJ, Matthew AG, Awasthi R, Bousquet-Dion G, Alibhai SMH, Au D, Fleshner NE, Finelli A, Clarke H, Aprikian A, Tanguay S, Carli F. Prehabilitation for radical prostatectomy: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Surg Oncol. 2018;27(2):289–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2018.05.010.

Shukla A, Granger CL, Wright GM, Edbrooke L, Denehy L. Attitudes and perceptions to prehabilitation in lung cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1534735420924466. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735420924466.

Solheim TS, Laird BJA, Balstad TR, Stene GB, Bye A, Johns N, Pettersen CH, Fallon M, Fayers P, Fearon K, Kaasa S. A randomized phase II feasibility trial of a multimodal intervention for the management of cachexia in lung and pancreatic cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8(5):778–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12201.

Stalsberg R, Bertheussen GF, Børset H, Thomsen SN, Husøy A, Flote VG, Thune I, Lundgren S. Do breast cancer patients manage to participate in an outdoor, tailored, physical activity program during adjuvant breast cancer treatment, independent of health and socio-demographic characteristics? J Clin Med. 2022;11(3):843. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11030843.

Steffens D, Young J, Beckenkamp PR, Ratcliffe J, Rubie F, Ansari N, Pillinger N, Koh C, Munoz PA, Solomon M. Feasibility and acceptability of a preoperative exercise program for patients undergoing major cancer surgery: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021;7(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-021-00765-8.

Thoft-Jensen B, Jensen JB, Love-Retinger N, Bowker M, Retinger C, Dalbagni G. Implementing a multimodal prehabilitation program to radical cystectomy in a comprehensive cancer center: a pilot study to assess feasibility and outcomes. Urol Nurs. 2019;39(6):303–13. https://doi.org/10.7257/1053-816x.2019.39.6.303.

Tweed TTT, Sier MAT, Van Bodegraven AA, Van Nie NC, Sipers WMWH, Boerma EG, Stoot JHMB. Feasibility and efficiency of the BEFORE (Better Exercise and Food, Better Recovery) prehabilitation program. Nutrients. 2021;13(10):3493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103493.

van Rooijen SJ, Molenaar CJL, Schep G, van Lieshout RHMA, Beijer S, Dubbers R, Rademakers N, Papen-Botterhuis NE, van Kempen S, Carli F, Roumen RMH, Slooter GD. Making patients fit for surgery: introducing a four pillar multimodal prehabilitation program in colorectal cancer. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;98(10):888–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000001221.

Waller E, Sutton P, Rahman S, Allen J, Saxton J, Aziz O. Prehabilitation with wearables versus standard of care before major abdominal cancer surgery: a randomised controlled pilot study (trial registration: NCT04047524). Surg Endosc. 2022;36(2):1008–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08365-6.

Waterland JL, Ismail H, Granger CL, Patrick C, Denehy L, Riedel B; Centre for Prehabilitation and Perioperative Care. Prehabilitation in high-risk patients scheduled for major abdominal cancer surgery: a feasibility study. Perioper Med.2022;11(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-022-00263-2

Wu F, Laza-Cagigas R, Pagarkar A, Olaoke A, El Gammal M, Rampal T. The feasibility of prehabilitation as part of the breast cancer treatment pathway. PM R. 2021;13(11):1237–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12543.

Agasi-Idenburg CS, Zuilen MK, Westerman MJ, Punt CJA, Aaronson NK, Stuiver MM. “I am busy surviving” - views about physical exercise in older adults scheduled for colorectal cancer surgery. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(3):444–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.05.001.

Banerjee S, Semper K, Skarparis K, Naisby J, Lewis L, Cucato G, Mills R, Rochester M, Saxton J. Patient perspectives of vigorous intensity aerobic interval exercise prehabilitation prior to radical cystectomy: a qualitative focus group study. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(8):1084–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1651907.

Beck A, Thaysen HV, Soegaard CH, Blaakaer J, Seibaek L. Investigating the experiences, thoughts, and feelings underlying and influencing prehabilitation among cancer patients: a qualitative perspective on the what, when, where, who, and why. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(2):202–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1762770.

Brady GC, Goodrich J, Roe JWG. Using experience-based co-design to improve the pre-treatment care pathway for people diagnosed with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(2):739–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04877-z.

Collaço N, Henshall C, Belcher E, Canavan J, Merriman C, Mitchell J, Watson E. Patients’ and healthcare professionals’ views on a pre- and post-operative rehabilitation programme (SOLACE) for lung cancer: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31(1–2):283–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15907.

Cooper M, Chmelo J, Sinclair RCF, Charman S, Hallsworth K, Welford J, Phillips AW, Greystoke A, Avery L. Exploring factors influencing uptake and adherence to a home-based prehabilitation physical activity and exercise intervention for patients undergoing chemotherapy before major surgery (ChemoFit): a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(9):e062526. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062526.

Daun JT, Twomey R, Dort JC, Capozzi LC, Crump T, Francis GJ, Matthews TW, Chandarana SP, Hart RD, Schrag C, Matthews J, McKenzie CD, Lau H, Culos-Reed SN. A Qualitative study of patient and healthcare provider perspectives on building multiphasic exercise prehabilitation into the surgical care pathway for head and neck cancer. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(8):5942–54. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29080469.

Ferreira V, Agnihotram RV, Bergdahl A, van Rooijen SJ, Awasthi R, Carli F, Scheede-Bergdahl C. Maximizing patient adherence to prehabilitation: what do the patients say? Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(8):2717–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4109-1.

Hogan SE, Solomon MJ, Carey SK. Exploring reasons behind patient compliance with nutrition supplements before pelvic exenteration surgery. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(5):1853–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4445-1.

McCourt O, Fisher A, Land J, Ramdharry G, Roberts AL, Bekris G, Yong. “What I wanted to do was build myself back up and prepare”: qualitative findings from the PERCEPT trial of prehabilitation during autologous stem cell transplantation in myeloma. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):348. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10799-1

Murdoch J, Varley A, McCulloch J, Jones M, Thomas LB, Clark A, Stirling S, Turner D, Swart AM, Dresser K, Howard G, Saxton J, Hernon J. Implementing supportive exercise interventions in the colorectal cancer care pathway: a process evaluation of the PREPARE-ABC randomised controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08880-8.

Sun V, Raz DJ, Kim JY, Melstrom L, Hite S, Varatkar G, Fong Y. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to a perioperative physical activity intervention for older adults with cancer and their family caregivers. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(2):256–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.06.003.

Wu F, Laza-Cagigas R, Rampal T. Understanding patients’ experiences and perspectives of tele-prehabilitation: a qualitative study to inform service design and delivery. Clin Pract. 2022;12(4):640–52. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract12040067.

Beck A, Vind Thaysen H, Hasselholt Soegaard C, Blaakaer J, Seibaek L. What matters to you? An investigation of patients’ perspectives on and acceptability of prehabilitation in major cancer surgery. Eur J Cancer Care. 2021;30(6): e13475. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13475.

Beck A, Vind Thaysen H, Hasselholt Soegaard C, Blaakaer J, Seibaek L. Prehabilitation in cancer care: patients’ ability to prepare for major abdominal surgery. Scand J Caring Sci. 2021;35(1):143–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.

Brahmbhatt P, Sabiston CM, Lopez C, Chang E, Goodman J, Jones J, McCready D, Randall I, Rotstein S, Santa Mina D. Feasibility of prehabilitation prior to breast cancer surgery: a mixed-methods study. Front Oncol. 2020;10:571091. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.571091.

Deftereos I, Hitch D, Butzkueven S, Carter V, Fetterplace K, Fox K, Ottaway A, Pierce K, Steer B, Varghese J, Kiss N, Yeung JM. Implementing a standardised perioperative nutrition care pathway in upper gastrointestinal cancer surgery: a mixed-methods analysis of implementation using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):256. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07466-9.

Low CA, Danko M, Durica KC, Kunta AR, Mulukutla R, Ren Y, Bartlett DL, Bovbjerg DH, Dey AK, Jakicic JM. A real-time mobile intervention to reduce sedentary behavior before and after cancer surgery: usability and feasibility study. JMIR Perioper Med. 2020;3(1):e17292. https://doi.org/10.2196/17292.

Macleod M, Steele RJC, O’Carroll RE, Wells M, Campbell A, Sugden JA, Rodger J, Stead M, McKell J, Anderson AS. Feasibility study to assess the delivery of a lifestyle intervention (TreatWELL) for patients with colorectal cancer undergoing potentially curative treatment. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e021117. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021117.

Mawson S, Keen C, Skilbeck J, Ross H, Smith L, Dixey J, Walters SJ, Simpson R, Greenfield DM, Snowden JA. Feasibility and benefits of a structured prehabilitation programme prior to autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in patients with myeloma; a prospective feasibility study. Physiotherapy. 2021;113:88–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2021.08.001.

Provan D, McLean G, Moug SJ, Phillips I, Anderson AS. Prehabilitation services for people diagnosed with cancer in Scotland-Current practice, barriers and challenges to implementation. Surgeon. 2022;20(5):284–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2021.08.005.

Waterland JL, Chahal R, Ismail H, Sinton C, Riedel B, Francis JJ, Denehy L. Implementing a telehealth prehabilitation education session for patients preparing for major cancer surgery. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):443. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06437-w.

Robinson R, Crank H, Humphreys H, Fisher P, Greenfield DM. Time to embed physical activity within usual care in cancer services: a qualitative study of cancer healthcare professionals’ views at a single centre in England. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;45(21):3484–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2134468.

Hewitt M, Simone JC. Ensuring access to cancer care. In: Hewit M, Simone JC, editors. Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. Washingon: National Academy Press; 1999. p. 46–78.

Dunn JG, Garvey PC, Valery D, Ball KM, Fong S, Vinod DL, O’Connell SK, Chambers. Barriers to lung cancer care: health professionals’ perspectives. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:497–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3428-3

Bourgeois A, Horrill TC, Mollison A, Lambert LK, Stajduhar KI. Barriers to cancer treatment and care for people experiencing structural vulnerability: a secondary analysis of ethnographic data. Int J Equity in Health. 2023;22:58 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-023-01860-3

Pearson SA, Taylor S, Marsden A, Dalton O’Reilly J, Krishan A, Howell S, Yorke J. Geographic and sociodemographic access to systemic anticancer therapies for secondary breast cancer: a systematic review. Systematic Reviews. 2024;13:35 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02382-3

Oksbjerg Dalton S, Halgren Olsen M, Moustsen IR, Wedell Andersen C, Vibe-Petersen J, Johansen C. Socioeconomic position, referral and attendance to rehabilitation after a cancer diagnosis: a population-based study in Copenhagen, Denmark 2010-2015. Acta Oncol. 201;58(5):730-736. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2019.1582800

Ross L, Petersen MA, Johnsen AT, Lundstrøm LH, Groenvold M. Are different groups of cancer patients offered rehabilitation to the same extent? A report from the population-based study “The Cancer Patient’s World.” Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(5):1089–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1189-6.

Kristiansen M, Adamsen L, Piil K, Halvorsen I, Nyholm N, Hendriksen C. A three-year national follow-up study on the development of community-level cancer rehabilitation in Denmark. Scand J Public Health. 2019;47(5):511–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494817746535.

Provan D, McLean G, Moug SJ, Phillips I, Anderson AS. Prehabilitation services for people diagnosed with cancer in Scotland - current practice, barriers and challenges to implementation. Surgeon. 2022;20(5):284–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2021.08.005.

Moak ZB, Agrawal A. The association between perceived interpersonal social support and physical and mental health: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Public Health (Oxf). 2010;32(2):191–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdp093.

Aartsen M, Veenstra M, Hansen T. Social pathways to health: On the mediating role of the social network in the relation between socio-economic position and health. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:419–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.05.006.

NHS Confederation in partnership with Google Health. Patient empowerment: what is the role of technology in transforming care? NHS Confederation. 2023. http://www.nhsconfed.org/publications/patientempowerment-what-role-technology-transforming-care#:~:text=Ensuring%20digital%20access%20and%20inclusion,-There%20are%20disparitiestext=Adopting%20a%20digitalfirst%20approach,and%20centre%20of%20the%20design. Accessed 25 Jan 2024.

Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-18.

Voorhees J, Bailey S, Waterman H, Checkland K. Accessing primary care and the importance of ‘human fit’: a qualitative participatory case study. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(718):e342–50. https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2021.0375.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.W. and JH wrote the main manuscript. E.G. Designed and tested the search strategy, ran all the searches and prepared supplementary file 1 E.G. and TW prepared figure 1 JH prepared figure 2 All authors contributed to study selection, quality assessment and data extraction TW and MP prepared supplementary file 2 TW prepared supplementary file 3 TW, MP and JH analysed data. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Watts, T., Courtier, N., Fry, S. et al. Access, acceptance and adherence to cancer prehabilitation: a mixed-methods systematic review. J Cancer Surviv (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-024-01605-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-024-01605-3