Abstract

Purpose

Theory-based interventions aimed at promoting health behavior change in cancer survivors seem to be effective but remain scarce. More information on intervention features is also needed. This review aimed to synthesize the evidence from randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of theory-based interventions (and its features) on physical activity (PA) and/or diet behaviors in cancer survivors.

Methods

A systematic search in three databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, and Web of Science) identified studies that (i) targeted adult cancer survivors and (ii) included theory-based randomized controlled trials designed to influence PA, diet, or weight management. A qualitative synthesis of interventions’ effectiveness, extensiveness of theory use, and applied intervention techniques was conducted.

Results

Twenty-six studies were included. Socio-Cognitive Theory was the most used theory, showing promising results in PA-only trials and mixed findings in multiple-behavior interventions. Mixed findings were observed for interventions based on the Theory of Planned Behavior and Transtheoretical Model. Limited findings were found in diet-only interventions. A large variability in the extensiveness of theory use, and in intervention techniques was found. Further research is required to understand how and why these interventions offer promise for improving behavior.

Conclusions

Theory-based interventions seem to improve PA and diet behaviors in cancer survivors. Further studies, including thorough intervention descriptions, are needed to confirm these findings and identify the optimal features and content of lifestyle theory-based interventions for cancer survivors.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

This systematic review can contribute to the development of more effective interventions to promote long-term adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Bruno Rodrigues and Eliana V. Carraça contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Background

Improvements in early detection/diagnostics and advances in treatment are leading to an increase in the number of cancer survivors, which brings new challenges to cancer care [1]. Cancer survivors suffer from several treatment side-effects, increased risk of recurrence, and higher vulnerability to other chronic diseases [2] that may increase survivors’ risk of poor mental and physical health–related quality of life, which can be improved through modifying behavioral and psychosocial risk factors.

Lifestyle behaviors, including physical activity (PA) and a healthy diet, are key to survivorship management [3]. PA has been consistently identified as an important adjunct therapy to be incorporated in cancer care [4], given that it optimizes health outcomes [5,6,7], and reduces the risk of recurrence [4], mortality from cancer and any cause [5], and improves treatment’s effectiveness and tolerance [8]. Diet also plays a major role in improving health. Cancer survivors with healthier diets and adequate nutritional status have an improved treatment response/tolerance, recovery, side-effect management, and disease outcomes [9,10,11,12,13]. Nonetheless, and despite the beneficial effects, only a minority of cancer survivors meet PA and healthy eating recommendations [14, 15]. Moreover, even when there is good compliance at the beginning of a lifestyle behavior change program, relapse is not uncommon [16,17,18].

There has been a growing body of evidence trying to understand which factors or interventions facilitate adherence to lifestyle recommendations [19, 20]. However, knowledge about what works best remains scarce. Implementing theory-based interventions has been recommended to improve behavior change effectiveness [16, 21, 22]. Theory-based interventions provide a better understanding of key mediators of change, explaining why interventions might succeed or fail [16, 23], and by connecting relevant theoretical determinants of the behavior to appropriate behavior change techniques [24]. Prior research has suggested that theory-based interventions seem more effective than atheoretical approaches, and interventions combining multiple theories and targeting several constructs appear to have larger effects on improving health behaviors [16, 25]. Although appearing effective [26, 27], these interventions remain scarce [28], and target mostly short-term adherence and outcomes [29]. Furthermore, there is little consensus on the most effective theories and on which behavior change techniques are (or should be) selected to best operationalize theoretical constructs and effectively change the behavior [30, 31]. Also, in practice, the extensiveness of theory use varies substantially, precluding the assessment of its impact on behavior change [32]. In other words, little is known about how theory is applied and contributes to behavior change effectiveness.

To our knowledge, there are no systematic reviews synthesizing the effects of theory-based behavior change interventions on both PA and diet in cancer survivors with multiple types of cancer, besides one addressing only social-cognitive theory-based interventions [27]. Although there is significant evidence supporting the benefits of diet and PA on health-related outcomes, there is still insufficient information on which interventions favor sustained behavior changes in cancer survivors. Also, it has been previously noted that further investigation into the active ingredients within an intervention and the type of behavioral theory used would be useful. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to synthesize the evidence on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the efficacy of theory-based behavior change interventions on PA and/or diet behaviors in cancer survivors. Specifically, this study seeks to (1) evaluate which theories are more effective to change PA and/or diet in cancer survivors, (2) assess the intensity of theory application in behavior change interventions, (3) investigate the relation between the extensiveness of theory use and intervention effectiveness, and (4) identify which behavior change techniques have been more often used within the interventions per theoretical framework, and if possible, which were more effective.

Methods

This systematic review is reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews [33]. This review was registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42021283338).

Eligibility criteria

To be included, studies had to (i) include adults aged ≥18 years, diagnosed with any type of cancer (at any point from diagnosis and stage of disease/treatment) and (ii) report on any theory-based RCT designed to influence PA and/or diet quality, including behavioral weight management interventions, typically targeting both lifestyle behaviors. The intervention group could be compared with any parallel control group with no intervention/waiting list, usual care, or other interventions. The outcomes could be PA levels/volumes and/or diet quality and adherence.

Observational and non-intervention studies, studies with no original data, dissertations/thesis, protocols, qualitative and pilot studies and studies not published in peer-reviewed journals were excluded. Studies with children, adolescents, pharmacological or surgical interventions targeting diet and PA were also excluded.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search of peer-reviewed articles published from inception until December 2022 (including online ahead of print publication) was conducted in three electronic databases — PubMed, PsychInfo, and Web of Science — using the following search strings: terms concerning the health condition or population of interest (e.g., Cancer, cancer survivor, cancer patient); terms concerning the intervention (e.g., Lifestyle/behavioral interventions); terms concerning the outcomes of interest (e.g., Diet, PA, weight loss/maintenance/change); and terms concerning the types of study (i.e., RCT).

A sample of the full search strategy is provided in Appendix 1. Searches were limited to English language and humans. Other searches included manual cross-referencing of literature cited in prior reviews, and hand-searches of the content of key scientific journals.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were screened for potential eligibility by three researchers (BBF, BR, and IN). These authors retrieved and screened the full text of potentially relevant articles. Decisions to include/exclude studies were made by consensus. When consensus was not achieved, disagreements were solved by a discussion with a fourth author (IS or EVC). The study selection procedure was conducted using the CADIMA software [34].

Data extraction and coding

A data extraction form was developed, informed by the PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews [33]. Data extraction was conducted by three authors (BBF, BR, and IN) and comprised information about the article, participants, brief intervention description, used theoretical frameworks, outcomes of interest, and main findings.

The extensiveness of theory application was assessed using a modified version of Michie and Prestwich’s behavior theory coding framework [35], as done in previous studies [36]. Eight items were selected across the six categories from the original coding framework to assess the intensity of theory application, from theory and construct identification to behavior change techniques used to operationalize theoretical constructs, or measurement of these constructs. Each item was classified as present or absent based on intervention descriptions provided in the included papers or others describing the same intervention (e.g., protocols). The eight items were (1) theory was mentioned, (2) relevant constructs were targeted, (3) each intervention technique was explicitly linked to at least one theoretical construct, (4) participants were selected/screened based on prespecified criteria (e.g., a construct or predictor), (5) interventions were tailored for different subgroups that vary on a psychological construct (e.g., readiness level), (6) at least one construct or theory mentioned in relation to the intervention was measured postintervention, (7) all measures of the theory were presented with some evidence of their reliability, and (8) results were discussed in relation to the theory. One author (BR) coded this information and a second author independently checked it (EVC). Disagreements were solved by consensus. A theory extensiveness score (n/8) was then calculated [36]. A “Sparse Use of Theory” (Level 1) was considered when studies fulfilled less than 4 items. A “Moderate Use of Theory” (Level 2) was considered when studies satisfied 4 or 5 items. An “Extensive Use of Theory” (Level 3) was considered when studies fulfilled 6 or more items.

Intervention techniques were coded as present or absent using the Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy v1 [37]. An intervention technique was only coded when there was clear evidence of its direct application to PA or diet. The total number of intervention techniques used and the congruence between those and the theoretical framework underpinning each intervention was assessed. Intervention protocols and related papers were consulted when available or felt necessary. One author (BR) coded this information and a second author independently checked it (EVC). Disagreements were solved by consensus.

Outcome measures

Total PA levels and/or PA discriminated by intensity or domains and dietary intake and/or diet quality constituted the primary outcomes of this review. Regarding PA, exercise energy expenditure (Kcal per day or week), volume (minutes per week or day), activity counts, step counts, or other measures of PA levels were considered. Concerning dietary intake, we considered caloric intake (Kcal per day or week), overall diet quality, and consumption (cup/ounces/grams/times/servings per day or week) of whole or refined grains, whole grain bread, fish, red and/or processed meat, fiber, alcohol, cruciferous, fruit, vegetables or fruit and vegetables.

Data synthesis

Characteristics of the included studies were qualitatively synthesized and presented in tabular form, organized by outcome, type and number of theories used in each intervention. The extensiveness of theory use was also reported by outcome. A matrix crossing intervention techniques with theoretical frameworks was built and organized by outcome and global use scores.

Study quality assessment

Study quality was assessed with an adapted version of the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project [38]. The current adaptation was based on recommendations from several authors [39,40,41] and has been previously used [39, 42]. This tool includes 19 items, organized into eight key methodological domains: study design, blinding, selection bias, withdrawals/dropouts, confounders, data collection, data analysis, and reporting. Each domain is classified as Strong, Moderate, or Weak based on specific criteria. A global rating is determined based on the scores of each component. Two researchers independently performed the quality assessment (BBF, IN). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. When consensus was not achieved, disagreements were solved by a discussion with a third author (BR or IS or EVC). Inter-rater agreement across categories varied from moderate (Cohen’s k=0.649) to strong (Cohen’s k=1.000).

Certainty assessment

Following the most recent PRISMA recommendations [33], the certainty of the evidence gathered in this review was assessed with the SURE checklist [43] by two researchers (BBF, IN). When consensus was not achieved, disagreements were solved by a discussion with a third author (BR or IS or EVC). This checklist includes 5 criteria to assess the identification, selection, and appraisal of studies; 5 criteria to evaluate how findings were analyzed in the review; and one criterion for other considerations. Based on the number and type of limitations identified, a conclusion regarding the degree of confidence in the evidence of a systematic review is obtained.

Results

Search results

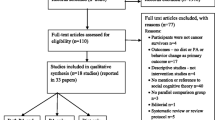

Database searches resulted in 2764 potentially relevant articles after duplicates removal. Of these, 2632 were excluded based on title/abstract, leaving 132 articles for full-text screening. Twenty-six articles met the eligibility criteria and were included. Figure 1 shows the studies flow diagram.

Studies’ characteristics

Table 1 summarizes (and Appendixes 2-4 detail) the characteristics of all included studies (N=26), synthesized by intervention topic: PA-only (N=15), diet-only (N=2), or multiple-behavior (PA and diet) (N=9).

Half of the studies (N=13) included both genders, one focused on men only [44], and twelve included women only [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. The mean age ranged from 46.1 to 66.5 years. Seventeen studies focused on one type of cancer, and in this subgroup, breast cancer (N=10) was the most studied cancer [45, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56], followed by colorectal (N=4) [57,58,59,60], endometrial (N=2) [46, 47], and prostate cancer (N=1) [44]. Two studies included two types of cancer (breast + prostate) [61], (colorectal + prostate) [62], and seven included ≥3 cancers [63,64,65,66,67,68,69]. Nine studies reported short-term changes (< 6 months), eight reported changes over 6 months, and the other nine reported both short- and long-term changes (maximum 36 months length).

Most studies (N=15) were based on a unique theory, ten were based on two, and one on more than three theories. The most used theory was Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) (N=17) [44,45,46,47,48, 50, 53,54,55,56, 59, 61,62,63, 67, 69], which includes Self-Efficacy Theory (a subset of Bandura’s SCT) mentioned in one trial [49], followed by the Transtheoretical Model (TTM; N=7) [48, 52, 55, 56, 59, 62, 63] and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; N=6) [51, 54, 58, 60, 68, 69]. Other theories mentioned were as follows: Health Action Process Approach (HAPA; N=3) [58, 62, 65], Integrated Model for Change (I-Change Model; N=2) [62, 64], Self-Regulation Theory (N=2) [62, 64], Self-Management Theory (N=1), Control Theory (N=1), Goal setting Theory (N=1), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (N=1) [66], Health Belief Model (N=1) [62], and Precaution Adoption Process Model (N=1) [62].

Diet-only trials evaluated dietary intake/nutritional composition with interviews using a nutrition data system and a nutrient database [44] or the Dietary Screener Questionnaire (DSQ) [63].

Regarding PA-only trials, one trial used an objective measure (accelerometer) to assess PA behavior change [53], while eight relied on self-reported measures including original or adapted versions of the Seven-Day Physical Activity Recall (7-PAR), the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ), the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ), the Leisure Score Index from Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (LSI), the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE), the Self-reported Short Questionnaire to Assess Health-enhancing PA (SQUASH), and the Total Physical Activity Questionnaire (TPAQ) [52, 56, 60, 65,66,67,68,69]. All others (N=6) assessed PA with both subjective and objective measures (accelerometer, pedometer, or a Fitbit®).

In the nine multiple-behavior trials, two types of dietary outcomes were evaluated, using self-reported measures and questionnaires: caloric intake [45,46,47,48, 61] and dietary intake [47, 57,58,59, 61, 64], with one study assessing overall diet quality using the 100-point Diet Quality Index-Revised score [61]. Regarding PA, two trials used an objective measure (accelerometer) to assess PA [48, 58], while six relied on self-reported measures, original or adapted (7-PAR, LSI, SQUASH), and an interviewer administered Modifiable Activity Questionnaire [45, 46, 57, 59, 61, 64]. One RCT assessed PA with both objective (pedometer) and subjective measures [47].

Synthesis of intervention effectiveness results

Results per outcome are detailed in Appendixes 2-4 and summarized in Table 2.

Diet-only trials

One trial was based on SCT [44], reporting significant improvements in every aspect of dietary intake. The other trial was based on SCT plus TTM, reporting significantly lower daily servings of processed meat at 9 and 15 weeks in the intervention group (IG), but non-significant differences in fruits and vegetables and whole grain consumption [63].

PA-only trials

Three trials used the TPB: two reported significant differences in PA from baseline to 1 year [60] and in total 3-month PA in the intervention subgroup of participants who initially reported ≤300 min/week of PA compared to the CG [68], while the other did not report significant results [51].

Of the two studies based on SCT, one reported a greater increase in minutes per week of moderate-vigorous PA (MVPA) in the intervention group (vs. controls), although not statistically tested [67], and the other reported significant improvements in objective PA at 3 months and in self-reported PA at 3 and 6 months, compared with the control group [50]. One trial was based on Self-Efficacy Theory (a subset of Bandura’s SCT), reporting significant differences in steps but not in self-reported PA between groups [49].

One trial was based on HAPA [65] and reported significant changes on self-reported PA at 4 weeks in the intervention group, but none at 14 weeks, compared to the control group. Interventions based on the Self-Management Theory [66], or the TTM [52], reported no between-group differences in subjective PA.

Six trials used a combination of different theories. Of these, five used a combination of SCT and another theory. The two interventions using SCT plus TPB showed an improvement in self-reported PA at 3 months [69] compared to the control arm. At 4 months, the tailored intervention group significantly reduced the odds of not doing any resistance-based PA, while increasing the odds of meeting resistance training guidelines [54]; no change was observed in the odds of meeting aerobic guidelines or mean daily steps. Other two trials used a combination of SCT plus TTM, showing increases in the intervention group’s (vs. controls) self-reported moderate PA [56] and in subjective and objective MVPA [55] at both 3 and 6 months, although this effect dissipated at 12 months [56]. One intervention used SCT plus Control Theory reporting significant differences in MVPA [53]. Finally, one trial [62] used a combination of multiple theories (SCT, TTM, HAPA, the I-Change Model, Health Belief model, goal setting theories, self-regulation theories and the Precaution Adoption Process Model), resulting in significant improvements in the intervention group’s self-reported MVPA and days with at least 30 min of PA at 3 months, and self-reported PA at 6 months. Objective MVPA also increased significantly in the intervention group, but objectively assessed days ≥30 min of PA was borderline significant.

Multiple-behavior trials

Four RCTs used SCT [45,46,47, 61]. Of these, one reported significant improvement in every aspect of diet intake (including caloric intake) in the intervention group (vs. controls) [47], and another one showed significant differences in the total percentage of calories from fat and in diet quality, although fruit and vegetable intake did not significantly differ between groups at the 2-year follow-up [61]. The remaining two studies reported non-significant differences in caloric intake [45, 46].

Regarding PA, one study reported significant improvements in self-reported PA at 3 months, and significant differences in steps/day, LSI and PA minutes at 6 months; at 12 months there were still significant differences in LSI and PA minutes [47]. The remaining three studies reported significant differences in PA measured with the LSI at 3, 6, and 12 months [46], and for daily caloric expenditure by the end of the 12-month intervention [45]. One study reported non-significant differences between groups [61].

One trial was based on the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy [57] and did not show significant group differences in fruit, fiber, or alcohol intake. Nevertheless, the intervention group was more likely to meet Australian PA recommendations than the controls.

Several trials used combinations of theories. Two trials used SCT plus TTM. One found that daily caloric intake improved within the intervention group, but not between groups [48]. The other found inconsistent improvements in fruit and vegetable consumption were reported using a two-item screening question, but not with the Food Frequency Questionnaire [59]. One study reported no significant changes in subjective PA [59], but showed increases in objectively measured MVPA [48] at 3 and 6 months.

TPB plus HAPA were used in one trial [58], showing significant increases in the odds of consuming less processed meat at all time-points and refined grain at months 6 and 24. In the subgroup of patients who had <300 min of MVPA per week at baseline, there was not a significant improvement in the two PA outcomes. However, patients who received PA interventions had larger increases in PA at months 6 and 18 than those who did not. One study was based on Self-Regulation Theory plus I-Change Model [64], with non-significant intervention effects in either diet or PA variables.

Extensiveness of theory use

Table 3 depicts the presence or absence of each indicator considered to calculate the extensiveness of theory use score by study and intervention target (diet, physical activity, or both). There was a vast heterogeneity across studies, but in general, the theoretical framework underpinning interventions was mentioned in all studies, and relevant constructs were targeted (except for two studies [47, 54]). On the other hand, only three studies [49, 50, 62] linked intervention techniques to at least one theoretical construct and no study selected/screened participants based on scores from a theory-related construct. Interventions were tailored to different subgroups that varied on a psychological construct in nine studies [52, 54, 56, 58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 69]. Twelve studies [44, 48, 49, 51, 55, 56, 59, 61, 63, 65, 67, 69] measured at least one construct or theory post-intervention, and 10 studies [49,50,51, 55, 56, 59, 63, 65, 67, 69] reported using reliable theory measures. Results were discussed in relation to theory in nine studies [49, 55, 56, 61, 63, 65,66,67, 69]. Overall, 15 studies [44,45,46,47,48, 50, 51, 53, 54, 57, 58, 60, 64, 66, 68] were classified with sparse use of theory (Level 1), 6 studies [59, 61,62,63, 65, 67] were classified with a moderate use of theory (Level 2), and 5 studies [49, 52, 53, 55, 56] were classified with an extensive use of theory (Level 3).

The relation between the extensiveness of theory use and intervention’s effectiveness was also explored (check superscript letters in the last column of Table 3). We found that interventions’ effectiveness appears to be independent of the extensiveness of theory use, given that only three interventions were ineffective in producing significant changes in the target outcomes; of these, two made sparse use of theory while the other made an extensive use; and, among effective interventions, the extensiveness of theory use varied substantially.

Intervention techniques

Table 4 shows a matrix matching the intervention techniques used by theory or theory combination, per target outcome and overall. A total of 46 different intervention techniques – BCTs were used (32 for diet; 43 for PA) in the interventions reported in the present review. In diet interventions, the most used BCTs were goal setting behavior (used 8 times), feedback on behavior and instruction on how to perform the behavior (both used 7 times), and problem solving, social support (unspecified) and review of behavior goals (all three used 6 times). In PA interventions, the most used BCTs were goal setting behavior and self-monitoring of behavior (both used 21 times), instruction on how to perform the behavior (used 18 times), and problem solving (used 16 times).

SCT was the most applied theoretical framework, with the number of BCTs used in these interventions being far greater than the number of BCTs used in interventions supported by other theoretical rationales (SCT: 25 BCTs for diet and 28 BCTs for PA; other theories around 12 BCTs for diet and 13 BCTs for PA, on average). Goal setting (4 for diet; 6 for PA), feedback on behavior (5 for diet; 5 for PA), instruction on how to perform the behavior (4 for diet; 5 for PA), graded tasks (3 for diet; 4 for PA), review of behavior goals (3 for diet; 3 for PA), self-monitoring of behavior (2 for diet; 5 for PA), biofeedback (4 for PA), demonstration of the behavior and behavioral practice/rehearsal (2 for diet; 4 for PA) were the most used BCTs in SCT-based interventions.

A large heterogeneity was observed, not only across interventions based on distinct theoretical frameworks, but also in interventions based on the same rationale. Hence, no single intervention used the same combination of BCTs. In addition, several interventions were based on different combinations of theories. This prevented us from assessing which BCTs were more effective in changing behavior, and understanding why or how the theories that appeared more effective work.

Risk of bias assessment

Results are reported in Appendix 5.

Both diet-only studies were classified with weak methodological quality [44, 63]. Of the fifteen PA-only studies, five were rated moderate [50, 54, 56, 66, 69], and ten weak [49, 51,52,53, 55, 60, 62, 65, 67, 68]. In multiple-behavior studies, three were rated with moderate [57,58,59] and six with weak quality [45,46,47,48, 61, 64].

The areas with a higher risk of bias were selection bias (all studies involved samples of volunteers) and blinding (not performed in several studies as interventions were rarely concealed from participants and/or outcome assessors). Seven studies did not control for confounders or did not describe them, being attributed a weak quality in this domain.

Assessment of evidence’s certainty

Results are reported in Appendix 6.

The SURE checklist [43] indicated that this systematic review has important limitations. Language bias was not avoided, considering that the search was restricted to papers written in English. Therefore, a more comprehensive search could have resulted in a higher number of retrieved papers. The list of excluded studies was not provided. Results could not be combined, and heterogeneity could not be explored due to methodological differences in studies and to the scarcity of studies per theory. Nevertheless, the findings of the current systematic review can be considered informative.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed at synthesizing the literature on theory-based behavior change interventions designed to improve PA and/or diet in cancer survivors, generally supporting their efficacy. Results indicated that diet-only interventions (although scarce) had beneficial effects on at least one aspect of diet (e.g., reducing the consumption of processed meat). Dietary changes were less consistent in multiple-behavior interventions, possibly because the primary focus of most of these trials was other than changing diet (e.g., weight reduction, improve PA or quality of life). Most multiple-behavior trials reported significant improvements in PA, as did most PA-only trials.

Regarding theoretical frameworks, SCT was the most used, followed by TTM and TPB. In diet-only interventions, SCT was used in isolation or combined with TTM, and though apparently effective, too few diet trials exist to date, demanding further exploration. PA-only trials based on SCT, used in isolation or combined with other theories, generally showed beneficial effects on PA. Our results mirror those reported in a recent meta-analysis [27], showing that SCT-based interventions resulted in meaningful changes in diet and PA behaviors in cancer survivors. This is especially true for diet-only and PA-only trials, but not so much for multiple-behavior trials, which in our systematic review led to mixed findings, possibly due to the different theoretical combinations, variability in the extensiveness of theory use, and large heterogeneity in the employed intervention techniques.

In line with prior research [70,71,72,73], interventions based on TPB and TTM led to mixed findings, with some studies pointing towards positive changes in the outcomes of interest, while others could not find significant effects. Additional studies are required to validate the efficacy of both these theories, especially in the field of nutrition/diet. On the other hand, HAPA-based interventions showed promising results, consistent with those of a pilot trial testing a HAPA-based intervention, which found significant increases in the frequency of breaks from sitting in full-time university students [74]. However, HAPA’s use is still limited and rarely in isolation. More interventions are thus required to confirm these findings.

Other theories were seldom used, making it difficult to draw conclusions about their effectiveness. Interestingly, no interventions based on Self-Determination Theory were found, though prior research has shown that internal motivations play an important role in long-term, sustained, behavior adoption [75,76,77], supporting its use as a valid framework.

The extensiveness of theory use in the interventions included in this review might explain the observed mixed findings. We found that more than half of the interventions made a sparse use of theory, rarely linking intervention techniques to theoretical constructs, selecting participants or tailoring interventions to subgroups based on psychological constructs. Measurement and interpretation of results in relation to theory were also inconsistent across studies. These results suggest that theory use was rather insubstantial, alerting once again for the necessary distinction between theory-informed interventions and theory-based interventions [78,79,80]. Studies included in this review were often not explicit about how the theory was operationalized, i.e., by specifying which theory-relevant determinants of behavior were targeted and how (through which intervention techniques). Interventions truly based on theory should include these aspects in their design [81, 82].

According to our findings, interventions’ effectiveness seems to be independent of the intensity of theory use. One aspect that might explain these results is the large variation in the target outcomes. Several and distinct dietary measures were used in the studies, as happened with PA measures. Every time an intervention presented a significant change in one of these measures, it was considered effective in the present review. We did/could not match effects by identical measures, which might have had an influence in these results. Also, besides the large variability in the extensiveness of theory use, the combinations of theories used varied substantially, preventing us from making more solid conclusions. Finally, we cannot discard the hypothesis that interventions with an extensive use of theory could turn out to be more effective in the long-term, throughout life. Most of the studies included in this systematic review reported on changes in diet and/or PA in the first 12 months (or less) following the intervention. It is known that times of adversity, like a cancer diagnosis, create a unique set of circumstances for behavior change whereby patients are met with a “teachable moment” [83]. Indeed, after active treatment completion, over half of cancer survivors are willing and feel able to participate in exercise [18] and report an increase in the number of health-related goals [84]. It is thus possible that in the long run, we could observe clearer distinctions in the outcomes of these interventions, perhaps greater in those interventions using theory more extensively, or using a certain theory or combination of theories.

The most used intervention techniques in the trials included in this review, and targeting changes in PA and/or diet, were goal setting of behavior, self-monitoring of behavior, feedback on behavior, instruction on how to perform the behavior, and problem solving, in line with previous systematic reviews in chronic disease populations [85, 86]. Still, a large heterogeneity was observed, not only across interventions based on distinct theoretical frameworks, but also in interventions based on the same rationale. No consistent (theory-congruent) combinations of techniques for improving PA or diet in this population were identified. In addition, interventions were based on varied combinations of theories. This prevented us from assessing which intervention techniques were more effective in changing behavior, or how the theories appearing more effective did work. The combination of techniques used might potentiate or suppress the effect of certain BCTs used in isolation, due to putative interaction effects, also depending on contextual factors and other intervention characteristics [87]. Moreover, interventions were not always described in sufficient detail, possibly leading to the inappropriate (mis) identification of BCTs in some of the interventions included in the current review. This issue has been previously observed [87,88,89]. The way the planned intervention is implemented afterwards might also influence its effectiveness, depending on the style of delivery or on the appropriateness of implementation of the selected techniques [90, 91].

This is the first review summarizing the evidence of RCTs evaluating the effects of multiple behavior change theories on both PA and/or dietary patterns in cancer survivors with multiple types of cancer, providing a broad overview of existing theory-based interventions in this population.

Limitations

The present systematic review has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. A broad definition of cancer survivors was considered herein, increasing the evidence’s breadth but contributing to increased heterogeneity across studies. The limited number of trials targeting diet only did not allow us to withdraw any conclusions regarding this type of intervention. PA outcomes were predominantly based on self-reported data and most interventions were unsupervised. Only two trials focused on promoting resistance-training, despite current PA recommendations [5], which precluded the exploration of effects across different PA types. More than two thirds of the studies were rated as “weak quality,” calling for improvements in research methodologies. Results could not be combined and quantitatively summarized due to methodological differences and to the scarcity of studies per theory (or combination of theories). Most interventions used theory sparsely, suggesting they were theory-informed rather than truly theory-based. Also, no consistent (theory-congruent) combinations of techniques for improving diet and/or PA were identified in this population. These findings call for more detailed descriptions of theory operationalization (which constructs were targeted and through which specific intervention techniques), greater standardization in the identification of employed intervention techniques (by using comprehensive taxonomies), assessments of the style of delivery and measures of implementation fidelity, which are clearly required and likely to have an impact on the determination of theory-based interventions’ effectiveness. Comparing the effectiveness of interventions using different theories through meta-analysis and assessing whether single or multiple health behavior interventions have the greatest benefit to improve health behaviors would also be useful gaps to address.

Clinical implications

Our review suggested that theory-based interventions are important to improve and maintain PA and diet behaviors in cancer survivors, but which theories or combinations of theories are more effective and why requires further investigation. Nevertheless, the available evidence seems to support the use of theory-based interventions, if carefully designed and planned. Clearly identifying which theoretical constructs will be targeted, through which intervention techniques, and how they will be measured is recommended if professionals are to truly understand how to effectively change the target behavioral outcomes, PA and diet, in cancer survivors.

Conclusions

This systematic review suggests that theory-based interventions seem important to improve PA and diet behaviors in cancer survivors. SCT was the most used theory, showing promising results in PA-only trials. Mixed findings were found for multiple-behavior interventions based on SCT, and for interventions based on TPB or TTM. Limited but potentially favorable findings were found in diet-only interventions and in HAPA-interventions. We found a large variability in the extensiveness of theory use and in the employed intervention techniques. Therefore, further research is required to corroborate our findings and understand how and why these interventions offer promise for improving behavior. This information can contribute to the development of more effective interventions to promote adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors. Notwithstanding the beneficial effects of the theory-based interventions included in this systematic review, more research is needed to identify the optimal features and content of lifestyle interventions for cancer survivors.

Data availability

Being a systematic review paper, all data is available on the articles included in the review. The full data extracted from the articles can be found in Appendixes 2-4.

References

Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, Soerjomataram I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 2021;127:3029–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33587.

Kenneth M, Laura T. Medical issues in cancer survivors - a review. J Cancer. 2008;14:375–87. https://doi.org/10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818ee3dc.

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100:126. https://doi.org/pmc/articles/PMC1424733/?report=abstract.

Cormie P, Zopf EM, Zhang X, Schmitz KH. The impact of exercise on cancer mortality, recurrence, and treatment-related adverse effects. Epidemiol Rev. 2017;39:71–92. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28453622/.

Patel AV, Friedenreich CM, Moore SC, Hayes SC, Silver JK, Campbell KL, Winters-Stone K, Gerber LH, George SM, Fulton JE, Denlinger C. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable report on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and cancer prevention and control. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(11):2391. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002117.

Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Snyder C, Geigle P, Gotay C. Are exercise programs effective for improving health-related quality of life among cancer survivors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum Oncology Nursing Society. 2014;41:E326–42. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.E326-E342.

Fiona C, James B-D. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2012;11:CD006145. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006145.pub3.

Hojman P, Gehl J, Christensen JF, Pedersen BK. Molecular mechanisms linking exercise to cancer prevention and treatment. Cell Metab. 2018;27:10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2017.09.015.

Ornish D, Lin J, Daubenmier J, Weidner G, Epel E, Kemp C, et al. Increased telomerase activity and comprehensive lifestyle changes: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1048–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70234-1.

Ornish D, Magbanua MJM, Weidner G, Weinberg V, Kemp C, Green C, et al. Changes in prostate gene expression in men undergoing an intensive nutrition and lifestyle intervention. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:8369–74. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0803080105.

Bodai BI, Tuso P. Breast cancer survivorship: a comprehensive review of long-term medical issues and lifestyle recommendations. Perm J. 2015;19:48–79. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/14-241.

Schwedhelm C, Boeing H, Hoffmann G, Aleksandrova K, Schwingshackl L. Effect of diet on mortality and cancer recurrence among cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutr Rev. 2016;74:737–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuw045.

Papadimitriou N, Markozannes G, Kanellopoulou A, Critselis E, Alhardan S, Karafousia V, et al. An umbrella review of the evidence associating diet and cancer risk at 11 anatomical sites. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4579. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24861-8.

Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2198–204. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6217.

Zhang FF, Liu S, John EM, Must A, Demark-Wahnefried W. Diet quality of cancer survivors and noncancer individuals: results from a national survey. Cancer. 2015;121:4212–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29488.

Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604.

Lee MS, Small BJ, Jacobsen PB. Rethinking barriers: a novel conceptualization of exercise barriers in cancer survivors. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22:1248–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1325503.

Blaney JM, Lowe-Strong A, Rankin-Watt J, Campbell A, Gracey JH. Cancer survivors’ exercise barriers, facilitators and preferences in the context of fatigue, quality of life and physical activity participation: a questionnaire-survey. Psychooncology. 2013;22:186–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.2072.

Lunde Husebø AM, Dyrstad SM, Søreide JA, Bru E, Professor A, Surgeon A, et al. Predicting exercise adherence in cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of motivational and behavioural factors. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:4–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04322.x.

Kampshoff CS, Stacey F, Short CE, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJM, Brug J, et al. Demographic, clinical, psychosocial, and environmental correlates of objectively assessed physical activity among breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:3333–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3148-8.

Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. 2015;9:323–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.941722.

Fishbein M, Yzer MC. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Commun Theory. 2003;13:164–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00287.x.

Nigg CR, Allegrante JP, Ory M. Theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research: common themes advancing health behavior research. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:670–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/17.5.670.

Bartholomew LK, Mullen PD. Five roles for using theory and evidence in the design and testing of behavior change interventions. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71:S20–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00223.x.

Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:673-93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673.

Grimmett C, Corbett T, Brunet J, Shepherd J, Pinto BM, May CR, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of maintenance of physical activity behaviour change in cancer survivors. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16:37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0787-4.

Stacey FG, James EL, Chapman K, Courneya KS, Lubans DR. A systematic review and meta-analysis of social cognitive theory-based physical activity and/or nutrition behavior change interventions for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:305–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-014-0413-z.

Rothman AJ, Baldwin AS, Hertel AW, Fuglestad PT. Self-regulation and behavior change: disentangling behavioral initiation and behavioral maintenance. In: Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, editors. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. The Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 106–22.

Courneya KS. Efficacy, effectiveness, and behavior change trials in exercise research. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:81. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-7-81.

Short CE, James EL, Stacey F, Plotnikoff RC. A qualitative synthesis of trials promoting physical activity behaviour change among post-treatment breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:570–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0296-4.

Pinto BM, Floyd A. Theories underlying health promotion interventions among cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24:153–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.003.

Wallace LM, Brown KE, Hilton S. Planning for, implementing and assessing the impact of health promotion and behaviour change interventions: a way forward for health psychologists. Health Psychol Rev. 2014;8:8–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2013.775629.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021:372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Kohl C, McIntosh EJ, Unger S, Haddaway NR, Kecke S, Schiemann J, et al. Online tools supporting the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews and systematic maps: a case study on CADIMA and review of existing tools. Environ Evid. 2018;7:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-018-0115-5.

Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol. 2010;29:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016939.

Bluethmann SM, Bartholomew LK, Murphy CC, Vernon SW. Use of theory in behavior change interventions: an analysis of programs to increase physical activity in posttreatment breast cancer survivors. Health Educ Behav. 2017;44:245–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198116647712.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-.

Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1:176–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x.

Mackenbach JD, Rutter H, Compernolle S, Glonti K, Oppert JM, Charreire H, et al. Obesogenic environments: a systematic review of the association between the physical environment and adult weight status, the SPOTLIGHT project. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-233.

Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM Statement. Oncol Res Treat. 2000;23:597–602. https://doi.org/10.1159/000055014.

Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D’Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7:1–173. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta7270.

Teixeira PJ, Carraça EV, Marques MM, Rutter H, Oppert JM, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lakerveld J, Brug Successful behavior change in obesity interventions in adults: a systematic review of self-regulation mediators. BMC Med. 2015 2022;13:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0323-6.

The SURE Collaboration. SURE guides for preparing and using evidence-based policy briefs 2011, Version 2.1. https://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/SURE-Guides-v2.1/Collectedfiles/sure_guides.html.

Parsons JK, Zahrieh D, Mohler JL, Paskett E, Hansel DE, Kibel AS, et al. Effect of a behavioral intervention to increase vegetable consumption on cancer progression among men with early-stage prostate cancer: the MEAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323:140–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.20207.

Sturgeon KM, Dean LT, Heroux M, Kane J, Bauer T, Palmer E, et al. Commercially available lifestyle modification program: randomized controlled trial addressing heart and bone health in BRCA1/2+ breast cancer survivors after risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;11:246–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0582-z.

Vivian G, Courneya KS, Gibbons HE, Kavanagh MB, Waggoner SE, Lerner E. Feasibility and effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention program in obese endometrial cancer patients: a randomized trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.12.026.

Gruenigen V, Frasure H, Kavanagh MB, Janata J, Waggoner S, Rose P, et al. Survivors of uterine cancer empowered by exercise and healthy diet (SUCCEED): a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:699–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.03.042.

Rogers LQ, Hopkins-Price P, Vicari S, Markwell S, Pamenter R, Courneya KS, et al. Physical activity and health outcomes three months after completing a physical activity behavior change intervention: persistent and delayed effects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1410–8. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1045.

Hirschey R, Kimmick G, Hockenberry M, Shaw R, Pan W, Page C, et al. A randomized phase II trial of MOVING ON: an intervention to increase exercise outcome expectations among breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2018;27:2450–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4849.

Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Anton PM, Hopkins-Price P, Verhulst S, Vicari SK, et al. Effects of the BEAT Cancer physical activity behavior change intervention on physical activity, aerobic fitness, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;149:109–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-3216-z.

Vallance JK, Friedenreich CM, Lavallee CM, Culos-Reed N, MacKey JR, Walley B, et al. Exploring the feasibility of a broad-reach physical activity behavior change intervention for women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer: a randomized trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:391–8. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0812.

Kong S, Lee JK, Kang D, Kim N, Shim YM, Park W, et al. Comparing the effectiveness of a wearable activity tracker in addition to counseling and counseling only to reinforce leisure-time physical activity among breast cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Cancers. 2021;13:2692. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112692.

Weiner LS, Takemoto M, Godbole S, Nelson SH, Natarajan L, Sears DD, et al. Breast cancer survivors reduce accelerometer-measured sedentary time in an exercise intervention. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2019;13:468–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00768-8.

Short CE, James EL, Girgis A, D’Souza MI, Plotnikoff RC. Main outcomes of the Move More for Life Trial: a randomised controlled trial examining the effects of tailored-print and targeted-print materials for promoting physical activity among post-treatment breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2015;24:771–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3639.

Pinto BM, Stein K, Dunsiger S. Peers promoting physical activity among breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2015;34:463–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000120.

Pinto BM, Papandonatos GD, Goldstein MG. A randomized trial to promote physical activity among breast cancer patients. Health Psychol. 2013;32:616–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029886.

Hawkes AL, Chambers SK, Pakenham KI, Patrao TA, Baade PD, Lynch BM, et al. Effects of a telephone-delivered multiple health behavior change intervention (CanChange) on health and behavioral outcomes in survivors of colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2313–21. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.5873.

Lee CF, Ho JWC, Fong DYT, MacFarlane DJ, Cerin E, Lee AM, et al. Dietary and physical activity interventions for colorectal cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24042-6.

Campbell M, Carr C, Devellis B, Switzer B, Biddle A, Amamoo MA, et al. A randomized trial of tailoring and motivational interviewing to promote fruit and vegetable consumption for cancer prevention and control. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38:71–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9140-5.

Courneya KS, Vardy JL, O’Callaghan CJ, Friedenreich CM, Campbell KL, Prapavessis H, et al. Effects of a structured exercise program on physical activity and fitness in colon cancer survivors: one year feasibility results from the CHALLENGE trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:969–77. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1267.

Mosher CE, Lipkus I, Sloane R, Snyder DC, Lobach DF, Demark-Wahnefried W. Long-term outcomes of the FRESH START trial: exploring the role of self-efficacy in cancer survivors’ maintenance of dietary practices and physical activity. Psychooncology. 2012;22:876–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3089.

Golsteijn RHJ, Bolman C, Volders E, Peels DA, de Vries H, Lechner L. Short-term efficacy of a computer-tailored physical activity intervention for prostate and colorectal cancer patients and survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0734-9.

Miller M, Li Z, Habedank M. A Randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of coping with cancer in the kitchen, a nutrition education program for cancer survivors. Nutrients. 2020;12:3144. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103144.

Kanera IM, CAW B, Willems RA, Mesters I, Lechner L. Lifestyle-related effects of the web-based Kanker Nazorg Wijzer (Cancer Aftercare Guide) intervention for cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10:883–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0535-6.

Ungar N, Sieverding M, Weidner G, Ulrich CM, Wiskemann J. A self-regulation-based intervention to increase physical activity in cancer patients. Psychol Health Med. 2016;21:163–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2015.1081255.

May AM, van Weert E, Korstjens I, Hoekstra-Weebers JEHM, van der Schans CP, Zonderland ML, et al. Improved physical fitness of cancer survivors: a randomised controlled trial comparing physical training with physical and cognitive-behavioural training. Acta Oncologica. 2008;47:825–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860701666063.

McGinnis EL, Rogers LQ, Fruhauf CA, Jankowski CM, Crisafio ME, Leach HJ. Feasibility of implementing physical activity behavior change counseling in an existing cancer-exercise program. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312705.

Bélanger LJ, Mummery WK, Clark AM, Courneya KS. Effects of targeted print materials on physical activity and quality of life in young adult cancer survivors during and after treatment: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2014;3:83–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2013.0021.

Webb J, Fife-Schaw C, Ogden J. A randomised control trial and cost-consequence analysis to examine the effects of a print-based intervention supported by internet tools on the physical activity of UK cancer survivors. Public Health. 2019;171:106–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.04.006.

Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health- related behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 1996;11:87–98. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-11.2.87.

McEachan RRC, Conner M, Taylor NJ, Lawton RJ. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2011;5:97–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2010.521684.

Darker CD, French DP, Eves FF, Sniehotta FF. An intervention to promote walking amongst the general population based on an “extended” theory of planned behaviour: a waiting list randomised controlled trial. Psychol Health. 2010;25:71–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440902893716.

Rhodes RE, Pfaeffli LA. Mediators of physical activity behaviour change among adult non-clinical populations: a review update. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-7-37.

Sui W, Prapavessis H. Standing up for student health: an application of the health action process approach for reducing student sedentary behavior—randomised control pilot trial. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2018;10:87–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12105.

Teixeira PJ, Carraça EV, Markland D, Silva MN, Ryan RM. Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:1–30. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-78.

Silva MN, Vieira PN, Coutinho SR, Minderico CS, Matos MG, Sardinha LB, et al. Using self-determination theory to promote physical activity and weight control: a randomized controlled trial in women. J Behav Med. 2010;33:110–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-009-9239-y.

Wyke S, Bunn C, Andersen E, Silva MN, van Nassau F, McSkimming P, et al. The effect of a programme to improve men’s sedentary time and physical activity: The European Fans in Training (EuroFIT) randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002736. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002736.

French SD, Green SE, O’Connor DA, McKenzie JE, Francis JJ, Michie S, et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implementation Science. 2012;7:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-38.

Michie S, Abraham C. Interventions to change health behaviours: evidence-based or evidence-inspired? Psychol Health. 2004;19:29–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044031000141199.

Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol [Internet]. Health Psychol. 2010;29:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016939.

Bartholomew LK, Mullen PD. Five roles for using theory and evidence in the design and testing of behavior change interventions. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71:S20–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00223.x.

Peters GJY, de Bruin M, Crutzen R. Everything should be as simple as possible, but no simpler: towards a protocol for accumulating evidence regarding the active content of health behaviour change interventions. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2013.848409.

Pinquart M, Nixdorf-Hänchen JC, Silbereisen RK. Associations of age and cancer with individual goal commitment. Appl Dev Sci. 2005;9:54–66. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads0902_2.

Pinquart M, Frohlich C, Silbereisen RK. Testing models of change in life goals after a cancer diagnosis. J Loss Trauma. 2008;13:330–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020701742052.

Carraça E, Encantado J, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell J, Busetto L, et al. Effective behavior change techniques to promote physical activity in adults with overweight or obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2021;22:e13258. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13258.

Hailey V, Rojas-Garcia A, Kassianos AP. A systematic review of behaviour change techniques used in interventions to increase physical activity among breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer. 2022;29:193–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-021-01323-z.

Michie S, West R, Sheals K, Godinho CA. Evaluating the effectiveness of behavior change techniques in health-related behavior: a scoping review of methods used. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8:212–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibx019.

Dombrowski SU, Sniehotta FF, Avenell A, Johnston M, MacLennan G, Araújo-Soares V. Identifying active ingredients in complex behavioural interventions for obese adults with obesity-related co-morbidities or additional risk factors for co-morbidities: a systematic review. 2010;6:7–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2010.513298.

Dombrowski SU, Sniehotta FF, Avenell A, Coyne JC. Current issues and future directions in Psychology and Health : towards a cumulative science of behaviour change: Do current conduct and reporting of behavioural interventions fall short of best practice? 2007;22:869–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440701520973.

Samdal GB, Eide GE, Barth T, Williams G, Meland E. Effective behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight and obese adults; systematic review and meta-regression analyses. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0494-y.

Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, McAteer J, Gupta S. Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2009;28:690–701. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016136.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). This work was supported by the PAC-WOMAN scientific project, funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology [grant numbers: PTDC/SAU-DES/2865/2020]. The funding agency played no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, and writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bruno Rodrigues (BR), Eliana V. Carraça (EVC), Beatriz Benquerença Francisco (BBF), and Inês Santos (IS) conceived the systematic review. BBF, BR, and Inês Nobre (IN) performed data searching, data extraction, and quality assessment. EVC, BR, and BBF drafted the manuscript, which was reviewed and supplemented by IN, Helena Cortez-Pinto (HCP), and IS. The final version of the manuscript was approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The present study does not involve human participants or animal subjects.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodrigues, B., Carraça, E.V., Francisco, B.B. et al. Theory-based physical activity and/or nutrition behavior change interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01390-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01390-5