Abstract

Purpose

To examine the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of online supportive care interventions targeting prostate cancer survivors (PCS).

Methods

Studies were identified through structured searches of PubMed, Embase and PsycINFO databases, and bibliographic review. Inclusion criteria were (1) examined feasibility, acceptability, or efficacy of an online intervention designed to improve supportive care outcomes for PCS; (2) presented outcome data collected from PCS separately (if mixed cancer); and (3) evaluated efficacy outcomes using randomized controlled trial (RCT) design.

Results

Sixteen studies met inclusion criteria; ten were classified as RCTs. Overall, 2446 men (average age 64 years) were included. Studies reported on the following outcomes: feasibility and acceptability of an online intervention (e.g., patient support, online medical record/follow-ups, or decision aids); reducing decisional conflict/distress; improving cancer-related distress and health-related quality of life; and satisfaction with cancer care.

Conclusion

We found good preliminary evidence for online supportive care among PCS, but little high level evidence. Generally, the samples were small and unrepresentative. Further, inadequate acceptability measures made it difficult to determine actual PCS acceptability and satisfaction, and lack of control groups precluded strong conclusions regarding efficacy. Translation also appears minimal; few interventions are still publicly available. Larger trials with appropriate control groups and greater emphasis on translation of effective interventions is recommended.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Prostate cancer survivors have a variety of unmet supportive care needs. Using online delivery to improve the reach of high-quality supportive care programs could have a positive impact on health-related quality of life among PCS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most prevalent cancer (excluding nonmelanoma skins cancers) among men in many developed countries around the world [1]. Advances in screening and treatment technology in the past 30–40 years have significantly improved the 5-year survival rate of prostate cancer from around 68% to present rates of over 90% [2]. Though survival rates are high, quality of life (QoL) during survivorship may be poor. Prostate cancer treatment has been associated with numerous physical and psychological short- and long-term side-effects that have a significant impact on QoL [3, 4]. For those men diagnosed with or having developed advanced prostate cancer (with a 5-year survival rate of 29% [5]), the effects of treatments and dealing with a poor prognosis have even larger affects [6].

In fact, a large proportion of men with prostate cancer have reported functional and psychosocial supportive care needs; many of which are going unmet [7,8,9]. Supportive care needs can be defined as the requirements for care during and after treatments to help manage potential symptoms and side effects, help adaptation and coping, facilitate understanding and inform decision-making, and reduce or minimize functional declines [10]. A recent review examined the supportive care needs of prostate cancer survivors and found some of the most commonly reported are related to intimacy, information, physical, and psychosocial needs [9]. A review of supportive care interventions for men with prostate cancer concluded that interventions with combinations of educational, cognitive-behavioral, communication, and peer support were generally effective among intervention completers [11]. However, only 40% of interventions indicated acceptable mean attendance, and one-quarter of intervention effects were moderated by sociodemographic or psychosocial variables [11]. From a public health point of view, this suggests the need to improve intervention reach and adherence, while also ensuring interventions are sufficiently tailored to address unique needs, which are influenced by individuals’ sociodemographic and psychosocial profiles.

It has been suggested that utilizing online delivery of supportive care interventions may help to improve reach, while also allowing for high quality tailored care at a low cost [12,13,14,15]. Firstly, online delivery allows anonymity. This means men are able to share their feelings or experience without fear of being emasculated [16,17,18]. It also allows men to benefit from observing discussions of others if they are not interested in active participation [19, 20]. Secondly, online delivery can provide increased access to a multidisciplinary team of health professionals, without the need to leave home. This may be especially important for those living in rural or remote areas, where access to urban treatment centers can be difficult. Online delivery also affords the convenience of participation at any time of day allowing patients to access care outside of regular office hours [21, 22]. Finally, compared with other distance-based approaches (e.g., print-materials, DVDs, telephone calls), online approaches have the capacity to provide not only high-quality content, but also highly tailored content. This, in addition to opportunities for interaction with others and tools designed to support self-management and decision-making [23] favors online delivery.

Recent reviews have begun to examine the utility of technology and online delivery in follow-up and supportive care interventions for cancer survivors [12, 13, 15]. While results have been promising, the utility of online interventions for supporting men with prostate cancer remains somewhat unclear. To date, reviews have focused on mixed cancer samples only, and have not explored cancer type as a moderator or reported prostate cancer specific results. This limits conclusion regarding the acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy of online supportive care interventions among men with prostate cancer, especially given that breast cancer survivors are typically over represented. For example, recent reviews examined the types and efficacy of online interventions that reported QoL or QoL-related health outcomes and the effect of eHealth in physical activity promotion among various cancer survivor groups [15, 24]. McAlpine and colleagues advocate for multidimensional interventions that incorporate methods for educating participants and allowing participants to interact with each other and health care providers [15]. However, of the 14 studies they identified, only two reported results for prostate cancer survivors [25, 26] and the review omitted any descriptive feasibility and user acceptance (satisfaction) data that was included in the studies. To inform the development and or dissemination of online supportive care interventions targeting men with prostate cancer a detailed synthesis of the prostate cancer specific research is warranted.

This review aims to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of online supportive care interventions targeting prostate cancer survivors. For the purpose of this review, online supportive care interventions are defined as interventions delivered via the internet (e.g., using a website, tablet, or mobile app) with the aim of meeting the informational, emotional, spiritual, social, and/or physical needs of patients during their diagnostic, treatment, or follow-up phase [27]. Patients are considered prostate cancer survivors if they have ever received a prostate cancer diagnosis. This includes those who are on active surveillance, those treated with curative intent and living disease free and those living with advanced prostate cancer. As the main aim of this review is to examine the potential of online interventions for delivering supportive care in any form, we have purposefully not targeted a specific stage of disease or treatment.

Method

The protocol for this review was registered a priori with PROSPERO (ID CRD42017056319). The conduct and reporting of the review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines [28]. A standardized form (based on ERC Cochrane template for intervention reviews [29]) was used to extract and review all data. A copy of the form is available via our open science framework page (http://osf.io/unj5m).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established a priori before conducting database searches. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they (1) examined the feasibility, acceptability, or efficacy of at least one online intervention designed to improve supportive care outcomes for prostate cancer survivors as a major part of the study; (2) presented outcome data collected from prostate cancer survivors only; and (3) evaluated efficacy outcomes using a randomized trial and/or feasibility/acceptability using a single-arm or randomized trial design. Studies were excluded if (1) they included mixed samples (e.g., survivors and caregivers, or survivors of mixed cancer types) and did not report study outcomes specifically for prostate cancer survivors; (2) the intervention being evaluated was targeted primarily at clinicians or caregivers rather than prostate cancer survivors; (3) findings were only explored using qualitative research methods; (4) findings were published in any language other than English; or (5) if findings were available as a conference abstract only.

Search strategy

Studies were primarily identified through a structured search of all publication years (until April 6, 2017) in the following electronic databases: PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO. The search strategy was developed in consultation with a specialist librarian at the University of Adelaide. Mesh terms in PubMed and equivalent terms in other databases were identified and used to search for all key concepts. Searches restricted to abstract and title were also undertaken for selected keywords. Boolean logic was used to combine the terms. The search strategy was piloted and refined in each database to achieve a balance between sensitivity (identifying high numbers of relevant articles) and specificity (identifying a low number of irrelevant articles) [30]. As a result, in PubMed and Embase, search terms relating to prostate cancer AND ehealth AND intervention evaluation AND supportive care outcomes were searched. Whereas, in PsycINFO, only terms related to prostate cancer AND ehealth AND intervention evaluation were searched. The search terms used for each database are detailed in additional file 1. The database searches were conducted by a single author (CES). In addition to the database search, endnote libraries of authors were reviewed and citation chaining was employed to identify additional articles of interest [30].

Study selection

All articles identified through the databases and hand searches were imputed into a citation manager. Duplicate records were then counted and removed. Two authors (CES and CF) independently screened all articles against the inclusion and exclusion criteria using a standardized form [29], taking title, abstract, and full-text into account. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed by the research team to extract information about the study setting, participant characteristics, study design, intervention characteristics, data collection methods, and findings relating to feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of the intervention. Feasibility and acceptability data was extracted for all included studies were reported. Efficacy data was only extracted for randomized trials. In cases where pilot data and definitive RCT data were both available (and focused on the same outcomes) only RCT data was extracted. If findings were unclear based on results reported in the manuscript, corresponding authors were emailed and asked to provide clarification.

The extraction form followed a recommended template [29] and was pilot tested by two reviewers (CF, CES) independently (on three included articles) to ensure it captured all relevant information and was easy to use. Minor changes were made after reviewing the first two articles, and no further changes were considered necessary after reviewing the third article. Data were then extracted using the form by a single reviewer (CF or CES). A second reviewer randomly selected four articles (i.e., 25%) and reviewed the data extracted (CF or CES). As there were no discrepancies, data extraction by a second reviewer for the remaining articles was considered unnecessary.

Methodological review

Methodological quality was assessed independently by two reviewers (CES and MM or CF and AF) using an existing tool [31]. Minor modifications to the tool were made to reflect current best practice recommendations regarding confounders in randomized trials [32, 33] and practical considerations surrounding blinding in psychological and health service research. Specifically, the risk of bias for confounding was based on whether likely confounders were accounted for at randomization or during data analysis, regardless of differences in participant characteristics at baseline. As blinding is difficult in this area, studies were given a ‘moderate’ rating by default [34]. Additionally, bias relating to dropout was assessed based on the immediate post-intervention follow-up rather than the final data collection point. This was to ensure that studies containing multiple follow-up points were not systematically rated as more biased compared to studies only reporting immediate post-intervention outcomes. Bias relating to data collection methods was assessed based on the primary outcome of interest for randomized controlled trials and for the main acceptability outcome measure for all other designs. All discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Outcomes

The following study integrity and recruitment feasibility outcomes were assessed: (1) the number of participants to enter the study, (2) reported recruitment obstacles, (3) representative samples, (4) if the intervention was implementation as intended, and (5) cost of implementation. Acceptability outcomes assessed included (1) intervention adherence rates; (2) assessments of participant engagement, acceptability, and appeal; (3) any intervention burden; and (4) number of adverse events. As with previous research, a 40% recruitment rate, 70% retention rate, and a 70% average attendance rate were deemed acceptable cut-points to assess feasibility [11, 35]. Outcomes relating to efficacy were varied and depended on the focus of the intervention. In each case, the change in supportive care outcome relative to the comparison group was reported. Efficacy outcomes were reported for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) only. Current availability of online interventions was determined by visiting the study URL, if included in the study, or by web search.

Results

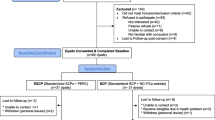

Study selection

A flowchart of the study selection process is presented in Fig. 1. A total of 1269 publications were identified from all sources. After removal of duplicates, 1089 titles and abstracts were screened, of which 64 were included in the full-text review. Of those, 16 studies were identified as eligible and included in full data extraction for this review.

Risk of Bias

Findings from the methodological review are presented in Table 1. Based on assessments from two reviewers, two of the studies [36, 37] received a global rating of “strong,” eight of the studies received a global rating of moderate [26, 35, 38,39,40, 43, 45, 48], and six received a global rating of “weak” [25, 41, 42, 44, 46, 47]. Studies with a weak rating tended to be small-sample single-arm studies designed to obtain preliminary insights into feasibility and acceptability.

Study characteristics

This review included 16 primary study papers [25, 26, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] and a further 16 associated papers describing pilot studies, evaluations, and prior research that informed the primary papers [12, 15, 49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. Included studies were conducted in six different countries (11 in USA [25, 35,36,37, 40,41,42,43, 45,46,47], one each in Australia [48], Canada [39], France [38], Germany [44], and Norway [26]). Ten of the 16 studies were classified as RCTs [25, 26, 35,36,37, 40, 41, 45, 47, 48]; however, one did not report any efficacy outcomes [41]. The remainder comprised of pre/post-test cohorts [39, 42, 43, 46], and a single study using a two-group quasi-experimental design [44] and one single group evaluation [38]. Study duration ranged from less than 1 h to 1 year.

Fifteen studies exclusively targeted men with prostate cancer [25, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]; one study included both breast and prostate cancer examined separately [26]. The total number of men with prostate cancer in all studies was 2446. Eleven studies included men with localized prostate cancer [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43, 45, 46, 48], one with advanced/metastatic disease [35], and four were either unknown or did not report stage information [25, 26, 44, 47]. Treatment types reported were active surveillance [43], surgery [26, 38, 44,45,46,47,48], radiotherapy [26, 45, 46, 48], hormone therapy [26, 35], and not yet had treatment [36, 37, 39,40,41,42]; one study did not report treatment type [25]. Detailed information on the study characteristics can be found in Table 2.

Intervention characteristics

Six of the evaluated studies were one-time interventions designed to improve knowledge and reduce decisional conflict prior to clinician visits [36, 37, 39,40,41,42]. Two interventions were designed to replace office visits; one 1-time “video visit” with the urologist [47] and one online medical record intervention, where patients could review their record and report symptoms for their doctor to review [38]. One 5-week intervention aimed to reduce uncertainty and increase self-care management among men during active surveillance [43]. Another 5-week intervention had men participate in one counseling session per week with the purpose of improving mental health [44]. An 8-week intervention for couples was designed to increase symptom management and communication skills [46]. A number of interventions aimed to improve one or more aspects of QoL and reduce distress; one 6-weeks [25], two 10-weeks [35, 48], one 12-weeks [45], one 1-year in length [26].

All interventions used some form of targeted or tailored education [25, 26, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], nine had expert involvement in the form of feedback or counseling [26, 35, 38, 43,44,45,46,47,48], three had interactive exercises or homework to complete [45, 46, 48], three had self-tracking for symptoms which would be evaluated by a health care practitioner [26, 38, 47], seven had aspects of social support in the form of chat groups, communication skill building, or videos [25, 26, 38, 41, 43, 46, 47], seven taught stress reduction or coping techniques [35,36,37, 41, 43, 45, 46, 48]. The majority were website-based interventions with one study using video conference to deliver the study instead [47], one incorporating CD-ROM options [41], and one delivered specifically via tablet using video conference [35]. Very few studies specified following a theory or framework when developing their interventions. Two studies indicated self-regulation theory guided them [40, 41] and two others indicated they structured the intervention following Cognitive Behavior Therapy frameworks [35, 48].

Feasibility and acceptability

Based on previous research among cancer patients [11, 35], six studies did not meet acceptable recruitment rates of 40% [25, 35, 38, 44, 45, 47], while three did not meet acceptable retention rates of 70% [43,44,45]. The average recruitment rate of 15 studies was 54% (ranging from 5 to 95%); one study did not report a response or recruitment rate [45]. The average overall retention rate was 78% (ranging from 31 to 100%). Of the 16 studies included, 9 reported a recruitment goal [26, 35,36,37, 41, 43, 44, 47, 48], of which 3 studies indicated meeting their goal [26, 37, 47]. Seven studies reported problems with recruitment [25, 36, 41, 43, 44, 46]. Potential reasons for recruitment issues were reported to be having a small number of men to sample from within a urological practice [43], too stringent eligibility criteria [25], wariness of technology [25, 44], burden of time commitment at stressful time [41], and call center recruitment issues [41]. In addition, one study indicated a large number of participants were lost after baseline measures due to long wait times getting the study started [44]. Few studies made any mention of implementation costs [25, 26, 38]; only one indicated the monetary cost of implementing the study [38]. Overall, the majority of studies required at least basic administrative time and maintenance on the part of either the researchers or the health care professional. Five studies reported intervention URLs [25, 26, 38, 44, 48] of which two [25, 44] were still active at time of data extraction. Detailed information on study feasibility can be found in Table 2.

Due to the variety of study designs apparent, intervention adherence was not assessed across all studies. Eight studies reported a percentage of participants that adhered in some way to the study parameters; the average “adherence rate” being 68% [35, 39, 41, 42, 45,46,47,48]. Outcomes of study adherence reported included participation in online sessions or modules [35, 43, 44, 47, 48], completing “homework” or extra modules [35, 45, 46], using a decision aid to completion [39], and sharing a decision aid summary page with a health care professional [39]. Usage data collected included time spent on a website, chat group or with a decision aid [35, 41, 44, 46, 59, 61], number of visits to a program or website [26, 38, 41, 43, 45, 46], and number of messages sent to health care provider or posted on a forum [26, 38, 48].

Most studies included one or more general measure of participant satisfaction [25, 35,36,37,38,39, 41, 43, 44, 46], with most participants reporting they were at least moderately satisfied with the program or intervention. Four studies reported high satisfaction with the quality of their cancer care rather than the intervention itself [40, 42, 46, 47]. One study did not report any satisfaction measures [26]. Four studies indicated that participants reported some kind of technical difficulty [38, 41, 47, 48], including incorrect data entry [40], absence of required software [12], general technical difficulties [41, 47, 61], and not knowing how to use the software [41]. No adverse events were reported in any study. Detailed information on the acceptability of the programs can be found in Table 3.

Efficacy

Efficacy outcomes are reported for RCTs only. Outcomes assessed included decisional conflict [36, 37, 40], QoL [25, 26, 35, 48], distress [26, 35, 45], sexual function and satisfaction [45], relationship satisfaction [45], health care provider visit efficiency [47], psychological distress [48], depressive symptoms [26, 35], social cognitive outcomes [26], cancer-related symptoms [25], and treatment preferences [40]. Of the nine RCTs reporting efficacy outcomes, three reported significant improvements in the primary outcome relative to the control [25, 40, 48]. In addition, two reported a significant intervention effect on a subscale of the primary outcome [26, 36], and one reported significant intervention effects on secondary outcomes [37]. One study reported improvements in the primary outcome among all intervention groups, resulting in no significant difference between groups [45]. Of the remaining studies, three reported no significant intervention effects compared to the control group (which included face-to-face visits in most cases [35, 47]) and one did not report efficacy data [41]. Detailed information on the efficaciousness of the interventions can be found in Table 4.

Decision making

Participants who received decision aids were more satisfied with their care and treatment decisions than those receiving standard care [36, 37, 39,40,41,42]. Three studies reported completing decision aids increases in self-reported knowledge, more confidence in their decision, and decreased uncertainty and decisional conflict compared to usual care [36, 37, 40, 41]. Participants that received a decision aid were less likely to be anxious about their decisions [40, 41]. Two studies reported that decision aids reduced distress [40, 41].

Quality of life

Participants that participated in an online support chat group reported improvements in QoL over time after treatment-related declines [25]. Participants that accessed a supportive online intervention reported improvements in QoL measures but not significantly different from the control group [26]. Access to cognitive behavioral therapy-based intervention only had an improvement in outlook compared to the forum groups. Those in the therapy group with forum access had reductions in regret compared to the forum only group indicating positive impact on PC-related QoL [48].

Sexual health

Participants that received internet-delivered sexual counseling had similar improvements in erectile function compared to face-to-face counseling [45] with no significant difference between the groups.

Mental health

Participants receiving access to an online supportive care intervention had improvements in depression measures [26]. Those that had access to a cognitive behavior therapy-based intervention had significantly better improvements in psychological distress than those with access to a chat forum only [48]. Another study that delivered cognitive behavioral stress management found no difference in cancer-related distress between groups but a trend toward reduced depressive symptoms in intention-to-treat analyses [35].

Visit efficiency

Studies that examined using online follow-ups or visits rather than face-to-face were also well received by participants [38, 47]. One study examined the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of video visits with an urologist rather than office visits and found no significant difference in any timing measure between the groups and estimated significantly less cost associated with the video group [47]. One study reported the amount of time for therapists to respond to email queries was less than time taken to conduct traditional therapy sessions [45].

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of online supportive care programs for men with prostate cancer. Overall, the results showed that using online delivery can be feasible and acceptable to men with prostate cancer; however, the field is still in its infancy. We found 16 studies that met our criteria among which 10 were randomized controlled trials. The results showed trends toward the programs being efficacious; however, among these trials, few were large enough to make meaningful conclusions on the efficacy of online supportive care programs, and selection bias was a consistent issue.

Though the average recruitment rate was 54%, only three of seven studies reporting recruitment goals met their goals. Recruitment is often a challenge in research studies among cancer survivors, particularly those targeting men [12, 62]. Collaborating with other centers to conduct multicenter trials may help to improve this to some extent. As well as increasing the recruitment pool, this may also help to recruit more representative samples, by ensuring participants are recruited from different geographical locations [63]. Another option would be to use multimodal recruitment strategies, such as social media ads combined with clinic-based recruitment as this has been shown to have similar advantages [26, 48]. As the majority of studies reviewed in this paper suffered from selection bias it is likely that the included sample is not entirely representative of the intended target group. Acceptability and efficacy findings should be interpreted with this in mind. In this sense, these results indicate that using online delivery for supportive care programs is feasible and acceptable, at least in some sub-groups of men with prostate cancer.

Despite the growing body of literature investigating online methods of providing patient support, we found only 16 studies met our inclusion criteria. There was little research among men with prostate cancer despite there being evidence of interest in supportive care programs among this population [16, 64, 65]. Furthermore, a large portion of the studies were testing decision aids for men who had localized prostate cancer and were yet to have any treatment. As one study points out, guidelines from the American Urological Association indicate that shared decision making is an important component of treatment counseling for men with localized disease [37]. These aids were seen as beneficial for men in increasing their knowledge about prostate cancer treatments and what treatment may be right for them, thereby reducing decisional conflict and regret. Only one study focused on men with advanced prostate cancer [35]. This restricts the generalizability of the conclusions to men with less severe forms of cancer.

While assisting men with prostate cancer to make informed treatment decisions is an important area of research, there are aspects of cancer care that have yet to be comprehensively addressed in this population. One area that warrants further attention in particular is the delivery of behavior change support. The studies included in this review focused mainly on psychological aspects of well-being, such as reducing distress, improving stress management and communication skills, and relationship satisfaction. However, activity levels, diet, and sleep behavior also impact QoL (both overall and disease specific) across the cancer continuum [66,67,68,69,70]. Structured exercise and physical activity in general have been shown to counteract prostate cancer related treatment toxicities, reduce disease progression in those with early stage disease, as well as improve psychosocial outcomes, and increase men’s sense of empowerment and control [69,70,71,72]. Additionally, online programs targeting physical activity and diet have been shown to be efficacious in other groups of cancer survivors [73]. It may be the case that interventions which encourage behavior change, such as physical activity, diet, and/or sleep, may be more effective and appealing to men than traditional psychological support, given that the outcomes (particularly those associated with exercise) often align with traditional masculine values [70]. However, additional high-quality research, particularly in prostate cancer, which assesses these outcomes objectively and longitudinally are required to not only establish their efficacy in targeting behavior change, but also supportive care needs [24, 73].

Summarizing results was difficult among the included studies as even those that focused on similar outcomes had measured or reported them differently. In addition, reporting of methods was lacking in many of the studies. As noted in Table 1 that summarizes the methodological review, only one study received a strong rating, five ranked weak and the remaining ten were ranked moderate. In order to grow this area of research, methods need be rigorously documented, as previous reviews have suggested [12, 14, 15, 62]. Lessons learned from previous research can greatly impact the body of literature by ensuring future studies build on what has been done previously.

While this study has been the first to summarize online supportive care interventions for men with prostate cancer, there are some study limitations that need to be mentioned. We understand that including only studies published in English reduced potential access to the total number of globally published studies. Furthermore, this study contained a high proportion of one-time clinical treatment decision support tools, and most studies had small samples or were pilot trials. This reflects the lack of variety of studies available, likely due to the infancy of this field and known issues with recruitment. Strengths of this study include a-priori protocol registration, the use of a standardized data-extraction form, the depth and range of data extracted, and synthesized and corroboration and consensus between a number of researchers during the data extraction and bias tool implementation. This allowed balanced assessments in which studies were fairly examined during the extraction and quality assessment stages of the review.

Aligned with previous research, we see a need for rigorous study development and reporting [11]. Methodological quality was generally weak mainly due to underreporting of methods. In order to build on or replicate results, clear description of the intervention components is necessary. Additionally, future research should ensure usage and adherence of individual intervention components are well reported. The majority of studies in this review included patients with localized disease. To address these research gaps, more focus should be on men with advanced disease and their specific supportive care needs.

Online supportive care may be particularly useful for clinicians as both decision aids and as a tool for patient follow-up. Many decision aids were able to be completed while waiting for a clinician or at home before an appointment. This allows men time to thoroughly examine the information and by sharing a report with their clinician, be more involved in the decision-making. For clinicians, this means less time devoted to treatment explanation in appointments and an increased feeling of shared decision making. Additionally, more than one study indicated that using online methods of follow-up, when possible, was just as efficient as office visits [25, 38, 47]. Clinicians spent the same, or fewer, minutes interacting with patients with no perceived reduction in quality of care. These methods may be more cost-effective for both clinicians and patients.

This review provides preliminary evidence in modest support of online supportive care programs for men with prostate cancer. Our conclusions are limited by the small number and weak methodological quality of studies found. A consistent call for well-documented, rigorously conducted studies has been noted in previous reviews and is echoed here.

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.1, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/old/FactSheets/cancers/prostate-new.asp.

Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):271–89. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21349.

Davis KM, Kelly SP, Luta G, Tomko C, Miller AB, Taylor KL. The association of long-term treatment-related side effects with cancer-specific and general quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Urology. 2014;84(2):300–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2014.04.036.

Gardner JR, Livingston PM, Fraser SF. Effects of exercise on treatment-related adverse effects for patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen-deprivation therapy: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(4):335–46.

Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2015. 2018.

Zajdlewicz L, Hyde MK, Lepore SJ, Gardiner RA, Chambers SK. Health-related quality of life after the diagnosis of locally advanced or advanced prostate cancer: a longitudinal study. Cancer Nurs. 2017;40(5):412–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0000000000000432.

Cockle-Hearne J, Charnay-Sonnek F, Denis L, Fairbanks HE, Kelly D, Kav S, et al. The impact of supportive nursing care on the needs of men with prostate cancer: a study across seven European countries. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(8):2121–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.568.

Hyde MK, Newton RU, Galvão DA, Gardiner RA, Occhipinti S, Lowe A, et al. Men’s help-seeking in the first year after diagnosis of localised prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2017;26(2):e12497. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12497.

Paterson C, Robertson A, Smith A, Nabi G. Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(4):405–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2014.12.007.

Ream E, Quennell A, Fincham L, Faithfull S, Khoo V, Wilson-Barnett J, et al. Supportive care needs of men living with prostate cancer in England: a survey. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(12):1903–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604406.

Chambers SK, Hyde MK, Smith DP, Hughes S, Yuill S, Egger S, et al. New Challenges in Psycho-Oncology Research III: a systematic review of psychological interventions for prostate cancer survivors and their partners: clinical and research implications. Psychooncology. 2017;26(7):873–913. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4431.

Hong Y, Peña-Purcell NC, Ory MG. Outcomes of online support and resources for cancer survivors: A systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(3):288–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.06.014.

Dickinson R, Hall S, Sinclair JE, Bond C, Murchie P. Using technology to deliver cancer follow-up: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-311.

Salonen A, Ryhänen AM, Leino-Kilpi H. Educational benefits of internet and computer-based programmes for prostate cancer patients: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(1):10–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.022.

McAlpine H, Joubert L, Martin-Sanchez F, Merolli M, Drummond KJ. A systematic review of types and efficacy of online interventions for cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(3):283–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.002.

Chambers SK, Hyde MK, Laurie K, Legg M, Frydenberg M, Davis ID et al. Experiences of Australian men diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2).

Chambers SK, Hyde MK, Oliffe JL, Zajdlewicz L, Lowe A, Wootten AC, et al. Measuring masculinity in the context of chronic disease. Psychol Men Masc. 2016;17(3):228–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000018.

Broom A. The eMale: prostate cancer, masculinity and online support as a challenge to medical expertise. J Sociol. 2005;41(1):87–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783305050965.

Han JY, Hou J, Kim E, Gustafson DH. Lurking as an active participation process: a longitudinal investigation of engagement with an online cancer support group. Health Commun. 2014;29(9):911–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.816911.

Kazer MW, Harden J, Burke M, Sanda MG, Hardy J, Bailey DE, et al. The experiences of unpartnered men with prostate cancer: a qualitative analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(2):132–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-010-0157-3.

Martin EC, Basen-Engquist K, Cox MG, Lyons EJ, Carmack CL, Blalock JA, et al. Interest in health behavior intervention delivery modalities among cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study. JMIR Cancer. 2016;2(1):e1. https://doi.org/10.2196/cancer.5247.

White SM, McAuley E, Estabrooks PA, Courneya KS. Translating physical activity interventions for breast cancer survivors into practice: an evaluation of randomized controlled trials. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37(1):10–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9084-9.

Short CE, Gelder C, Binnewerg L, McIntosh M, Turnbull D. Examining the accessibility of high-quality physical activity behaviour change support freely available online for men with prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(1):10–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0638-8.

Haberlin C, O’Dwyer T, Mockler D, Moran J, O’Donnell DM, Broderick J. The use of eHealth to promote physical activity in cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:3323–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4305-z.

Osei DK, Lee JW, Modest NN, Pothier PK. Effects of an online support group for prostate cancer survivors: a randomized trial. Urol Nurs. 2013;33(3):123–33.

Ruland CM, Andersen T, Jeneson A, Moore S, Grimsbø GH, Børøsund E, et al. Effects of an internet support system to assist cancer patients in reducing symptom distress: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(1):6–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e31824d90d4.

Fitch MI. Supportive care framework. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2008;18(1):6–24.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Data Collection Form. EPOC resources for review authors. Oslo2013.

The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2011.

Effective Public Health Practice Project. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies2003.

de Boer MR, Waterlander WE, Kuijper LDJ, Steenhuis IHM, Twisk JWR. Testing for baseline differences in randomized controlled trials: an unhealthy research behavior that is hard to eradicate. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0162-z.

Austin PC, Manca A, Zwarenstein M, Juurlink DN, Stanbrook MB. A substantial and confusing variation exists in handling of baseline covariates in randomized controlled trials: a review of trials published in leading medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(2):142–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.002.

Chambers SK, Pinnock C, Lepore SJ, Hughes S, O'Connell DL. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for men with prostate cancer and their partners. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):e75–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.027.

Yanez B, McGinty HL, Mohr DC, Begale MJ, Dahn JR, Flury SC, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a technology-assisted psychosocial intervention for racially diverse men with advanced prostate cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(24):4407–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29658.

Berry DL, Halpenny B, Hong F, Wolpin S, Lober WB, Russell KJ, et al. The personal patient profile-prostate decision support for men with localized prostate cancer: a multi-center randomized trial. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(7):1012–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.10.004.

Berry DL, Hong F, Blonquist TM, Halpenny B, Filson CP, Master VA, et al. Decision support with the personal patient profile-prostate: a multi-center randomized trial. J Urol. 2017;199:89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2017.07.076.

Cathala N, Brillat F, Mombet A, Lobel E, Prapotnich D, Alexandre L, et al. Patient followup after radical prostatectomy by Internet medical file. J Urol. 2003;170(6):2284–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000095876.39932.4a.

Davison BJ, Szafron M, Gutwin C, Visvanathan K. Using a web-based decision support intervention to facilitate patient-physician communication at prostate cancer treatment discussions. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2014;24(4):241–7.

Diefenbach MA, Mohamed NE, Butz BP, Bar-Chama N, Stock R, Cesaretti J, et al. Acceptability and preliminary feasibility of an internet/CD-ROM-based education and decision program for early-stage prostate cancer patients: randomized pilot study. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(1):262–75. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1891.

Fleisher L, Wen KY, Miller SM, Diefenbach M, Stanton AL, Ropka M, et al. Development and utilization of complementary communication channels for treatment decision making and survivorship issues among cancer patients: The CIS Research Consortium Experience. Internet Interv. 2015;2(4):392–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2015.09.002.

Johnson DC, Mueller DE, Deal AM, Dunn MW, Smith AB, Woods ME, et al. Integrating patient preference into treatment decisions for men with prostate cancer at the point of care. J Urol. 2016;196(6):1640–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2016.06.082.

Kazer MW, Bailey DE Jr, Sanda M, Colberg J, Kelly WK. An internet intervention for management of uncertainty during active surveillance for prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38(5):561–8. https://doi.org/10.1188/11.ONF.561-568.

Lange L, Fink J, Bleich C, Graefen M, Schulz H. Effectiveness, acceptance and satisfaction of guided chat groups in psychosocial aftercare for outpatients with prostate cancer after prostatectomy. Internet Interv. 2017;9:57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2017.06.001.

Schover LR, Canada AL, Yuan Y, Sui D, Neese L, Jenkins R, et al. A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. 2012;118(2):500–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26308.

Song L, Rini C, Deal AM, Nielsen ME, Chang H, Kinneer P, et al. Improving couples’ quality of life through a web-based prostate cancer education intervention. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42(2):183–92.

Viers BR, Lightner DJ, Rivera ME, Tollefson MK, Boorjian SA, Karnes RJ, et al. Efficiency, satisfaction, and costs for remote video visits following radical prostatectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2015;68(4):729–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.002.

Wootten AC, Abbott JAM, Meyer D, Chisholm K, Austin DW, Klein B, et al. Preliminary results of a randomised controlled trial of an online psychological intervention to reduce distress in men treated for localised prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68(3):471–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.024.

Berry DL, Halpenny B, Bosco JL, Bruyere J Jr, Sanda MG. Usability evaluation and adaptation of the e-health Personal Patient Profile-Prostate decision aid for Spanish-speaking Latino men. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-015-0180-4.

Berry DL, Halpenny B, Wolpin S, Davison BJ, Ellis WJ, Lober WB, et al. Development and evaluation of the personal patient profile-prostate (P3P), a Web-based decision support system for men newly diagnosed with localized prostate cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(4):e67. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1576.

Berry DL, Wang Q, Halpenny B, Hong F. Decision preparation, satisfaction and regret in a multi-center sample of men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(2):262–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.04.002.

Børøsund E, Cvancarova M, Ekstedt M, Moore SM, Ruland CM. How user characteristics affect use patterns in web-based illness management support for patients with breast and prostate cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(3):e34. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2285.

Diefenbach AM, Butz PB. A multimedia interactive education system for prostate cancer patients: development and preliminary evaluation. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(1):e3. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.1.e3.

Grimsbø GH, Engelsrud GH, Ruland CM, Finset A. Cancer patients’ experiences of using an Interactive Health Communication Application (IHCA). International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2012;7:https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v7i0.15511. doi:https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v7i0.15511.

Marcus AC, Diefenbach MA, Stanton AL, Miller-Halegoua SN, Fleisher L, Raich PC, et al. Cancer patient and survivor research from the cancer information service research consortium: a preview of three large randomized trials and initial lessons learned. J Health Commun. 2013;18(5):543–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.743629.

Ruland CM, Jeneson A, Andersen T, Andersen R, Slaughter L, Bente Schjodt O, et al. Designing tailored Internet support to assist cancer patients in illness management. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2007:635–9.

Ruland CM, Maffei RM, Borosund E, Krahn A, Andersen T, Grimsbo GH. Evaluation of different features of an eHealth application for personalized illness management support: cancer patients’ use and appraisal of usefulness. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82(7):593–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.02.007.

Stanton AL, Morra ME, Miller SM, Diefenbach MA, Slevin-Perocchia R, Raich PC, et al. Responding to a significant recruitment challenge within three nationwide psycho-educational trials for cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):392–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0282-x.

Wolpin S, Halpenny B, Sorrentino E, Stewart M, McReynolds J, Cvitkovic I, et al. Usability testing the “personal patient profile-prostate” in a sample of African American and Hispanic men. Comput Inform Nurs. 2016;34(7):288–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/cin.0000000000000239.

Wootten AC, Meyer D, Abbott JM, Chisholm K, Austin DW, Klein B, et al. An online psychological intervention can improve the sexual satisfaction of men following treatment for localized prostate cancer: outcomes of a Randomised Controlled Trial evaluating My Road Ahead. Psychooncology. 2016;26(7):975–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4244.

Wootten AC, Abbott JAM, Chisholm K, Austin DW, Klein B, McCabe M, et al. Development, feasibility and usability of an online psychological intervention for men with prostate cancer: My Road Ahead. Internet Interv. 2014;1(4):188–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2014.10.001.

Dale HL, Adair PM, Humphris GM. Systematic review of post-treatment psychosocial and behaviour change interventions for men with cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19(3):227–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1598.

Sung NS, Crowley WF Jr, Genel M, et al. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA. 2003;289(10):1278–87. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.10.1278.

Nanton V, Appleton R, Loew J, Ahmed N, Ahmedzai S, Dale J. Men don’t talk about their health, but will they CHAT? The potential of online holistic needs assessment in prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2017;121(4):494–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14114.

Rising CJ, Bol N, Kreps GL. Age-related use and perceptions of eHealth in men with prostate cancer: a web-based survey. JMIR Cancer. 2015;1(1):e6. https://doi.org/10.2196/cancer.4178.

Phillips SM, Stampfer MJ, Chan JM, Giovannucci EL, Kenfield SA. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and health-related quality of life in prostate cancer survivors in the health professionals follow-up study. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(3):500–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0426-2.

Courneya KS, Rogers LQ, Campbell KL, Vallance JK, Friedenreich CM. Top 10 research questions related to physical activity and cancer survivorship. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2015;86(2):107–16.

Langford DJ, Lee K, Miaskowski C. Sleep disturbance interventions in oncology patients and family caregivers: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(5):397–414.

Galvão DA, Taaffe DR, Spry N, Gardiner RA, Taylor R, Risbridger GP, et al. Enhancing active surveillance of prostate cancer: the potential of exercise medicine. Nature Reviews Urology. 2016;13:258–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2016.46.

Galvão DA, Taaffe DR, Spry N, Joseph D, Newton RU. Combined resistance and aerobic exercise program reverses muscle loss in men undergoing androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer without bone metastases: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):340–7.

Cormie P, Oliffe JL, Wootten AC, Galvão DA, Newton RU, Chambers SK. Improving psychosocial health in men with prostate cancer through an intervention that reinforces masculine values – exercise. Psychooncology. 2016;25(2):232–5. doi:doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3867.

Chipperfield K, Fletcher J, Millar J, Brooker J, Smith R, Frydenberg M et al. Factors associated with adherence to physical activity guidelines in patients with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22(11):2478–86. doi:doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3310.

Roberts AL, Fisher A, Smith L, Heinrich M, Potts HWW. Digital health behaviour change interventions targeting physical activity and diet in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(6):704–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0632-1.

Funding

CES, AF, MM, and SS were supported by the Freemasons Foundation Centre for Men’s health to conduct this research. CES was also supported by an Early Career Fellowship (ID 1090517) from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. CCF was supported by an Australia Awards—Endeavour Research Fellowship from the Australian Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This review does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Forbes, C.C., Finlay, A., McIntosh, M. et al. A systematic review of the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of online supportive care interventions targeting men with a history of prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv 13, 75–96 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0729-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0729-1