Abstract

In the past, the use of face masks in western countries was essentially limited to occupational health. Now, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, mask-wearing has been recommended as a public health intervention. As potential side effects and some contraindications are emerging, we reviewed the literature to assess the impact of them in daily life on patient safety and to provide appropriate guidelines and recommendations. We performed a systematic review of studies investigating physiological impact, safety, and risk of masks in predefined categories of patients, which have been published in peer-reviewed journals with no time and language restrictions. Given the heterogeneity of studies, results were analyzed thematically. We used PRISMA guidelines to report our findings. Wearing a N95 respirator is more associated with worse side effects than wearing a surgical mask with the following complications: breathing difficulties (reduced FiO2, SpO2, PaO2 increased ETCO2, PaCO2), psychiatric symptoms (panic attacks, anxiety) and skin reactions. These complications are related to the duration of use and/or disease severity. Difficulties in communication is another issue to be considered especially with young children, older person and people with hearing impairments. Even if benefits of wearing face masks exceed the discomfort, it is recommended to take an “air break” after 1–2 h consecutively of mask-wearing. However, well-designed prospective studies are needed. The COVID-19 pandemic could represent a unique opportunity for collecting large amount of real-world data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of face masks (FMs) has become widespread as part of a multi-faceted approach to limit spread of the COVID-19 virus. In the past, use of the mask was limited to occupational health and safety settings, as well as use by individuals to combat impact of air pollution, allergies, and risk of infection in immunosuppressed people The increased use during the pandemic has highlighted problems in their use.

As of December 2021, more than 86% of the world's population lived in countries that recommended or mandated FMS in public; more than 130 countries have mandated the masks [1] The wearing of masks along with physical distancing or during exercise has been contentious [1, 2].

A well-performing FM must have the following four basic ergonomic requirements:

-

(1) Protect the respiratory system from the polluting or infectious agent.

-

(2) Allow adequate ventilation.

-

(3) Fit the face well.

-

(4) Ensure good protection and comfort during normal activities.

The demand for masks has led to new approaches to the design of face masks [3]. Different types of FMs are listed in Table 1 [3, 4].

Rationale for the review

Reports on potential side effects of mask wearing led us to query the safety implications of wearing masks [5]. The side effects include a false sense of security, reduced compliance with other measures

and contraindications to mask wearing including young children, persons with breathing difficulties or who are unconscious, incapacitated, etc. [4].

Methods

We performed a systematic review of published studies investigating the safety of FMs categorized to different groups, i.e., children, pregnant women, patients with neurodegenerative diseases, cognitive impairment, obesity, lung/cardiac/renal diseases, psychiatric disorders, eye or upper airway diseases. We searched Medline/PubMed and EMBASE using the search strategy reported in Supplemental files, with no time and language restrictions.

The search and screening process was independently conducted by two researchers (MLR and DDS) with no time restrictions. Reports were considered potentially eligible for this review if they assessed the safety, risks and/or the respiratory impact of FMs. We included papers about the impact of FMs on communication, especially in noisy environments. Figure 1 shows the study selection process. Exclusion criteria were as follows: papers not peer reviewed, not focused on risks, safety or impact on respiratory function, no reported exposure to any type of face mask, not focused on age range or disease. From each paper we extracted the following: authors’ names, year of publication, study design, sample size, safety indicators and/or respiratory parameters, safety and/or respiratory outcomes.

Given the heterogeneity of studies, results were analyzed thematically. We used PRISMA guidelines to report our findings.

Consensus recommendations

Following the systematic review, we arbitrary selected a panel of specialists with experience and/or interest in patient safety (1 gynecologist, 1 pediatrician, 3 internists, 1 pulmonologist, 1 ear-nose- throat specialist, 1 public health and 2 occupational medicine physician, 1 ergonomist, 1 coroner) to address specific recommendations. A Delphi consensus approach was used [6]. A detailed document with a research evidence summary, including methodological details of included papers, was sent to each panelist who reviewed the document and gave their own recommendations for any thematic area anonymously with the rationale for their proposal. All statements with the associated rationale of the proposal were sent back to the panelists to choose one option in any thematic area. We conducted three rounds to reach an acceptable level of consensus.

Results

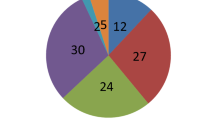

Our research retrieved 3718 papers, of which 3577 were excluded after title/abstract screening, 66 after full test reading and 19 because of duplication; seven papers were identified from the reference list. We included 63 eligible papers, published between 1995 and January 2022. Details are provided in Table 2. We divided them into 12 thematic categories according to the investigated population/safety issues.

Key lessons from all the papers are that each group may experience challenges to wearing masks. In each category there are specific challenges. These include the following:

-

Discomfort (in all groups).

-

Impact on respiratory function in people with respiratory disease, children, elderly, people with heart disease.

-

Irritation of the skin especially for people with skin disease.

-

Communication problems for people with a hearing loss.

-

Issues with mask reuse.

Side effects with respirators [53,54,55,56] include concentration problems, reduced working capacity [56], respiratory difficulties [48, 56,57,58], fogging glasses, difficulty with facial recognition and psychiatric symptoms. Headache was reported after prolonged use.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review on FMs-related patient safety issues. We have assessed the safety, the risks and/or the respiratory physiological impact of FMs in age ranges or disease categories. We could not pool data as in a meta-analysis, nor could we cover the entire spectrum of diseases as too few papers were retrieved and they were heterogeneous in nature.

In Table 3 we summarize the recommendations based on our review to facilitate safe evidence- based use of FMs in different categories.

Published evidence suggests that mask-related safety issues included the following:

-

Increased breathing resistance with subsequent increased respiratory effort.

-

Decreased FiO2 and increased FiCO2.

-

Inconvenience in the face, head, and neck areas, increased humidity, temperature, pressure on the nose, around the ear lobes.

-

Psychosocial effects.

In addition, there may be inadequate protection to people who cannot tighten their face properly due to malformations or a following an operation of the skull or face.

Pregnant women have an increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19 and are at a higher risk for preterm birth and stillbirth and other pregnancy complications [72]. Interactions between FMs use and pregnancy-related rhinitis, induced airway changes (increased breathing resistance and residual volume loss) and pregnancy-related dyspnea remain to be solved [70]. Wearing FM during childbirth is not associated with any adverse outcome for mothers or newborns [73].

Most of the studies noted that the pandemic negatively affected people’s mental health. Mask- wearing is associated with mask-related panic attacks, worsening mood, depressive symptoms, anxiety and sense of suffocating [48, 49, 57]. People with mental health can have difficulties to follow the recommendations due to their disorders [45, 46]. For example, children with ASD for example, struggle to tolerate FMs for more than 15 minutes [50, 51].

Most people with Alzheimer Disease had no knowledge of the pandemic and did not wear the masks properly even with help, leading to increased risk of infection [34, 35]. We retrieved only an expert opinion paper about people with epilepsy. FMs may induce hyperventilation which can activate seizure activity [74].

People who have had a laryngectomy have an anatomical and/or surgical alteration of the upper airways that enhances susceptibility to contagion. They require multiple protection [75] in people with allergies and rhinopathology FMs have an advantage of preventing exposure to pollen grains [24, 25], but in 70% with and without chronic rhinitis the FM seemed to decrease the quality of life [76].

The literature regarding FMs and eye disease showed that not only there are mask-related symptoms: MADE (mask-associated dry eye), eye irritation and inflammation can cause increased face touching and spread of COVID-19. Artifacts could also occur in the results of the examination of the visual field [29,30,31,32,33].

The literature on physical exercise and FMs is limited. In general, FFP2/N95 masks are perceived as more uncomfortable than surgical mask [27]. Exercising at low or moderate intensity when wearing FM can prevent an increased risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and depression [36, 37].

Common SMs are responsible for a loss of hearing more than 20% while F-PPE (e.g. FFP3 masks combined with a face shield) could cause a reduction of almost 70% and significant verbal communication issues [77] to improve intelligibility without altering physical distance, the clinician had to increase the voice volume increasing the risk of loss of confidentiality [78]. Using written order and/or read-back procedure, speech-to-text mobile apps, written scripts (e.g., chalkboard) or masks with a plastic transparent panel over the mouth, make communication easier for hearing impairment patients [79].

In children N95 respirator wearing is associated with a reduced FiO2 and/or SpO2and/or PaO2 and an increased ETCO2 and/or PaCO2, proportionally to the duration of use and disease severity [7]. Recommendations for children are provided by the CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics [70, 71].

Safety of FMs have not been yet investigated in patients with heart failure, gastroesophageal reflux, obesity, adenoid hypertrophy, and cognitive impairment.

Extended use, reuse, or decontamination of SMs and N95 respirators may result in inferior protection. Some evidence suggests that reused and makeshift mask should be used when medical- grade protection is unavailable [68]. Reuse of masks has also led to a debate given the cost and the environmental impact of discarded masks. The most frequent methods used are the decontamination with hot water and ethanol or specific cleanser because it is more suitable for people to perform at home. Information campaigns are required to promote the correct use of masks and limit the infection rate [68].

With the greater obligation to use FM, some recommendations should be made on legal medical issues. The emergency has forced governments to act based on two opposing and antithetical presumptions. In particular, the policy of mandatory mask wearing was established by assuming that the population was a potential vector of infection and that the use of FMs was free from side effects. However, not being able to go out or enter a place without a mask can be considered a restriction of individual freedoms. Similarly, a contraction of the fundamental and inalienable right to health could occur when the obligation involves individuals suffering from specific pathological conditions which could be aggravated by wearing a mask.

Nonetheless, according to current evidence, the use of FMs is complementary to other measures such as physical distance and hand hygiene. Therefore, to reconcile personal protection with public health needs, it is recommended that we recommend appropriate and safe use [80] of FMs through targeted educational campaigns and more detailed guidelines rather than solely through mandating, because the reduction of the virus and the benefits of wearing FMs outweigh the discomfort [58].

Limitations

We may have missed minor papers with our search strategy as there are no specific terms to univocally indicate protective FMs. In addition, recommendations change when new evidence is published. Finally, published papers do not provide data on major clinically relevant outcomes, such as adverse effect-related diseases or hospitalization. Evidence on respiratory impact in sick/frail subjects and mask-related patient safety issues is limited and heterogeneous; current expert-opinion recommendations need to be validated with large scale studies.

Conclusions

In general, evidence demonstrates that benefits of wearing face masks exceed discomfort; anyway an “air break” after 1–2 hours consecutively of mask-wearing can be a good practice for people with respiratory function compromised by diseases or in particular conditions (i.e. pregnancy, epilepsy, etc.). The present COVID-19 pandemic, where different public health agencies and governments have recommended universal use of FMs, represents a unique opportunity for collecting large amount of real-world data.

References

Masks4All.(2021) "What Countries RequireMasks in Public or Recommend Masks?" https://masks4all.co/what-countries-require-masks-in-public/ (Last Update December 2021)

Setti L, Passarini F, De Gennaro G (2020) Airborne transmission route of COVID-19: why 2 meters/6 feet of inter-personal distance could not be enough. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(8):2932

US Food and Drug Administration (2021) N95 Respirators, Surgical Masks, and Face Masks https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/personal-protective-equipment-infection-control/n95-respirators-surgical-masks-and-face-masks (Last Update 15th September 2021)

Center for Disease Prevention and Control (2022). Types of Masks and Respirators, available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/types-of-masks.html. (Last Update 28th January 2022)

Lazzarino AI, Steptoe A, Hamer M, Michie S (2020) COVID-19: important potential side effects of wearing face masks that we should bear in mind. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2003

Jones J, Hunter D (1995) Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 311:376–380

Goh DYT, Mun MW, Lee WLJ, Teoh OH, Rajgor DD (2019) A randomised clinical trial to evaluate the safety, fit, comfort of a novel N95 mask in children. Sci Rep 9(1):18952

Lubrano R, Bloise S, Testa A, Marcellino A, Dilillo A, Mallardo S, Isoldi S, Martucci V, Sanseviero M, Del Giudice E, Malvaso C, Iorfida D, Ventriglia F (2021) Assessment of respiratory function in infants and young children wearing face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Jama Netw Open 4(3):e210414

Schwarz S, Jenetzky E, Krafft H, Maurer T, Martin D (2021) Coronakinderstudien „Co-Ki “: erste Ergebnisse eines deutschlandweiten Registers zur Mund-Nasen-Bedeckung (Maske) bei Kindern [Corona child studies “Co-Ki”: first results of a Germany-wide register on mouth and nose covering (mask) in children]. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 169(4):353–365

Kyung SY, Kim Y, Hwang H, Park JW, Jeong SH (2020) Risks of N95 face mask use in subjects with COPD. Respir Care 65(5):658–664

Bansal S, Harber P, Yun D, Liu D, Liu Y, Wu S, Ng D, Santiago S (2009) Respirator physiological effects under simulated work conditions. J Occup Environ Hyg 6(4):221–227

Harber P, Yun D, Santiago S, Bansal S, Liu Y (2011) Respirator impact on work task performance. J Occup Environ Med 53(1):22–26

Schönhofer B, Rosenblüh J, Kemper P, Voshaar T, Köhler D (1995) Einfluss des Mundschutzes auf die Atemarbeit bei Patienten mit chronischer Belastung der Atempumpe [Effect of a face mask on work of breathing in patients with chronic obstructive respiratory disease]. Pneumologie 49(Suppl 1):209–211 (German)

Samannan R, Holt G, Calderon-Candelario R, Mirsaeidi M, Campos M (2021) Effect of face masks on gas exchange in healthy persons and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 18(3):541–544

Ciocan C, Clari M, Fabbro D, De Piano ML, Garzaro G, Godono A, Gullino A, Romano C (2020) Impact of wearing a surgical mask on respiratory function in view of a widespread use during COVID-19 outbreak. A case – series study. Med Lav 111(5):354–364

Faria N, Costa MI, Gomes J, Sucena M (2021) Reduction of severe exacerbations of COPD during COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal: a protective role of face masks? COPD. J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2021.1904387

Mendel LL, Gardino JA, Atcherson SR (2008) Speech understanding using surgical masks: a problem in health care? J Am Acad Audiol 19(9):686–695

Chodosh J, Weinstein BE, Blustein J (2020) Face masks can be devastating for people with hearing loss. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2683

Ten Hulzen RD, Fabry DA (2020) Impact of hearing loss and universal face masking in the COVID-19 Era. Mayo Clin Proc 95(10):2069–2072

Atcherson SR, Mendel LL, Baltimore WJ, Patro C, Lee S, Pousson M, Spann MJ (2017) The effect of conventional and transparent surgical masks on speech understanding in individuals with and without hearing loss. J Am Acad Audiol 28(1):58–67

Trecca EMC, Gelardi M, Cassano M (2020) COVID-19 and hearing difficulties. Am J Otolaryngol 41(4):102496

Langrish JP, Li X, Wang S, Lee MM, Barnes GD, Miller MR, Cassee FR, Boon AN, Donaldson K, Li J, Li L, Millis LN, Newby DE, Jiang L (2012) Reducing personal exposure to particulate air pollution improves cardiovascular health in patients with coronary heart disease. Environ Health Perspect 120(3):367–372

Vos TG, Dillon MT, Buss E, Rooth MA, Bucker AL, Dillon S, Pearson A, Quinones K, Richter ME, Roth N, Young A, Dedmon MM (2021) Influence of protective face coverings on the speech recognition of cochlear implant patients. Laryngoscope 00:1–6

Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Marshak T, Layous E, Zigron A, Shivatzki S, Morozov NG, Taiber S, Alon EE, Ronen O, Zusman E, Srouji S, Sela E (2020) Reduction of allergic rhinitis symptoms with face mask usage during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 8:10

Kishore Dayal A, Sinha V (2020) Trend of allergic rhinitis post COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective observational study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-020-02223-y

Klimek L, Huppertz T, Alali A, Spielhaupter M, Hörmann K, Matthias C, Hagemann J (2020) A new form of irritant rhinitis to filtering facepiece particle (FFP) masks (FFP2/N95/ KN95 respirators) during COVID- 19 pandemic. World Allergy Organ J 13:100474

Fikenzer S, Uhe T, Lavall D, Rudolph U, Falz R, Busse M, Hepp P, Laufs U (2020) Effects of surgical and FFP2/N95 face masks on cardiopulmonary exercise capacity. Clin Res Cardiol 109(12):1522–1530

Kao TW, Huang KC, Huang YL, Tsai TJ, Hsieh BS, Wu MS (2004) The physiological impact of wearing an N95 mask during hemodialysis as a precaution against SARS in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Formos Med Assoc 103(8):624–628

Laura B (2021) Self-reported symptoms of mask-associated dry eye: a survey study of 3605 people. Contact Lens Anterior Eye. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2021.01.003

Moshirfar M, West WB, Marx DP (2020) Face mask-associated ocular irritation and dryness. Ophthalmol Ther 9:397–400

Bayram N, Gundogan M, Ozsaygili C, Vural E, Cicek A (2021) The impacts of face mask use on standard automated perimetry results in glaucoma patients. J Glaucoma 30(4):287–292

Young SL, Smith ML, Tatham AJ (2020) Visual field artifacts from face mask use. J Glaucoma 29:989–991

El-Nimri NW, Moghimi S, Fingeret M, Weinreb RN (2020) Visual field artifacts in glaucoma with face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Glaucoma 29:1184–1188

Gil R, Arroyo-Anllò EM (2020) Alzheimer’s disease and face masks in times of COVID-19. J Alzheimer’s Dis. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-201233

Kobayashi R, Hayashi H, Kawakatsu S, Morioka D, Aso S, Kimura M, Otani K (2021) Recognition of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and face mask wearing in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: an investigation at a medical center for dementia in Japan. Psychogeriatrics. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12617

Epstein D, Korytny A, Isenberg Y, Marcusohn E, Zukermann R, Bishop B, Raz MS, S, Miller A. (2021) Return to training in the COVID-19 era: the physiological effects of face masks during exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sport 31(1):70–75

Chandrasekaran B, Fernandes S (2020) Exercise with facemask; are we handling a devil’s sword? – A physiological hypothesis. Med Hypotheses 144:110002

Veraldi S, Angileri L, Barbareschi M (2020) Seborrheic dermatitis and anti-COVID-19 masks. J Cosmet Dermatol 19(10):2464–2465

Zuo Y, Hua W, Luo Y, Li L (2020) Skin reactions of N95 masks and medial masks among health-care personnel: a self-report questionnaire survey in China. Contact Dermatitis 83(2):145–147

Szepietowski JC, Matusiak L, Szepietowska M, Krajewski PK, Białynicki-Birula R (2020) Face mask-induced itch: a self-questionnaire study of 2.315 responders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Derm Venereol 100(10):adv00152

Han C, Shi J, Chen Y, Zhang Z (2020) Increased flare of acne caused by long-time mask wearing during COVID- 19 pandemic among general population. Dermatol Ther 33(4):e13704. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.13704

Park S, Han J, Yeon YM, Kang NY, Kim E (2020) Effect of face mask on skin characteristics changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Skin Res Technol. https://doi.org/10.1111/srt.12983

Han HS, Shin SH, Park JW, Li K, Kim BJ, Yoo KH (2021) Changes in skin characteristics after using respiratory protective equipment (medical masks and respirators) in the COVID-19 pandemic among health care workers. Contact Dermat. https://doi.org/10.1111/cod.13855

Techasatian L, Lebsing S, Uppala R, Thaowandee W, Chaiyarit J, Supakunpinyo C, Panombualert S, Mairiang D, Saengnipanthkul S, Wichajarn K, Kiatchoosakun P, Kosalaraksa P (2020) The effects of the face mask on the skin underneath: a prospective survey during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Prim Care Community Health 11:1–7

Jung H, Park C, Kim M, Jhon M, Kim J, Ryu S, Lee J, Kim J, Park K, Jung YB, Kim S (2021) Factors associated with mask wearing among psychiatric inpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Schizophr Res 228:235–236

Uvais NA (2020) Use of face masks among patients with psychiatric illnesses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 22(6):20br02789

Soh KC, Khanna R, Parsons A, Visa B, Ejareh DM (2021) Masks in Melbourne: an inpatient mental health unit’s COVID-19 experience. Australas Psychiatry 29(2):240–241

Battista RA, Ferraro M, Piccioni LO, Malzanni GE, Bussi M (2021) Personal protective equipment (PPE) in COVID 19 pandemic: related symptoms and adverse reactions in healthcare workers and general population. J Occup Environ Med 63(2):e80–e85

Wu S, Harber P, Yun D, Bansal S, Li Y, Santiago S (2011) Anxiety during respirator use: comparison of two respirator types. J Occup Environ Hyg 8(3):123–128

Sivaraman M, Virues-Ortega J, Roeyers H (2020) Telehealth mask wearing training for children with autism during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Appl Behav Anal 54(1):70–86

Halbur M, Kodak T, McKee M, Carroll R, Preas E, Reidy J, Cordeiro MC (2021) Tolerance of face coverings for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Appl Behav Anal 54(2):600–617

Kalra S, Chaudhary S, Kantroo V, Ahuja J (2020) Mask fatigue. J Pak Med Assoc 70:12

Lim EC, Seet RC, Lee KH, Wilder-Smith EP, Chuah BY, Ong BK (2006) Headaches and the N95 facemask amongst healthcare providers. Acta Neurol Scand 113(3):199–202

Ong JJY, Bharatendu C, Goh Y, Tang JZY, Sooi KWX, Tan YL, Tan BYQ, Teoh HL, Ong ST, Allen DM, Sharma VK (2020) Headaches associated with personal protective equipment - a cross-sectional study among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19. Headache 60(5):864–877

Ramirez-Moreno JM, Ceberino D, Gonzalez Plata A, Rebollo B, Macias Sedas P, Hariramani R, Roa AM, Constantino AB (2020) Mask-associated ‘de novo’ headache in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Occup Environ Med 78(8):548–554

Farronato M, Boccalari E, Del Rosso E, Valentina Lanteri V, Mulder R, Maspero C (2020) A scoping review of respirator literature and a survey among dental professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(16):5968

Cheok GJW, Gatot C, Sim CHS, Ng YH, Tay KXK, Howe TS, Koh JSB (2021) Appropriate attitude promotes mask wearing in spite of a significant experience of varying discomfort. Infect Dis Health 26(2):145–151

Scheid JL, Lupien SP, Ford GS, West SL (2020) Commentary: physiological and psychological impact of face mask usage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:6655

Honarbakhsh M, Jahangiri M, Farhadi P (2017) Effective factors on not using the N95 respirators among health care workers: application of Fuzzy Delphi and Fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (FAHP). J Healthc Risk Manag 37(2):36–46

MacIntyre CR, Wang Q, Cauchemez S, Seale H, Dwyer ED, Yang P, Shi W, Gao Z, Pang X, Zhang Y, Wang X, Duan W, Rahman B, Ferguson N (2011) A cluster randomized clinical trial comparing fit-tested and non-fit-tested N95 respirators to medical masks to prevent respiratory virus infection in health care workers. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 5(3):170–179

Czypionka T, Greenhalgh T, Bassler D, Bryant MB (2021) Masks and face coverings for the lay public: a narrative update. Ann Intern Med 174(4):511–520

Thomas F, Allen C, Butts W, Rhoades C, Brandon C, Handrahan DL (2011) Does wearing a surgical facemask or N95-respirator impair radio communication? Air Med J 30(2):97–102

Baig AS, Knapp C, Eagan AE, Radonovich LJ Jr (2010) Health care workers’ views about respirator use and features that should be included in the next generation of respirators. Am J Infect Control 38(1):18–25

Or PP, Chung JW, Wong TK (2018) A study of environmental factors affecting nurses’ comfort and protection in wearing N95 respirators during bedside procedures. J Clin Nurs 27(7–8):e1477–e1484

Bothra A, Das S, Singh M, Pawar M, Meheswari A (2020) Retroauricular dermatitis with vehement use of ear loop face masks during COVID19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 34(10):e549–e552

İpek S, Yurttutan S, Güllü UU, Dalkıran T, Acıpayam C, Doğaner A (2021) Is N95 face mask linked to dizziness and headache? Int Arch Occup Environ Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01665-3

Duong MC, Nguyen HT, Duong BT (2021) A cross-sectional study of knowledge, attitude, and practice towards face mask use amid the COVID-19 pandemic amongst university students in Vietnam. J Community Health 46(5):975–981

Scalvenzi M, Villani A, Ruggiero A (2020) Community knowledge about the use, reuse, disinfection and disposal of masks and filtering facepiece respirators: results of a study conducted in a dermatology clinic at the university of Naples in Italy. J Community Health 46(4):786–793

Cho Kwan R, Hong Lee P, Sze Ki Cheung D, Ching Lam S (2021) Face mask wearing behaviors, depressive symptoms, and health beliefs among older people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Med 8:590936

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Children, teens, and young adults. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/caring-for-children.html (Last Update 2nd August 2021)

American Academy of Pediatrics (2022) Masks and children during COVID-19 https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/COVID-19/Pages/Cloth-Face-Coverings-for-Children-During-COVID-19.aspx (Last Update 12th January 2022)

Center for Disease Prevention and Control (2022) Pregnant and recently pregnant people at increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19 https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/pregnant-people.html. (Last Update 24th January 2022)

Dap M, Bertholdt C, Belaisch-Allart J, Huissoud C, Morel O (2021) Le port du masque pendant les efforts expulsifs: quel impact réel surles modalité s d’accouchement? [Wearing a mask during childbirth: what real impact on delivery issues?]. Gynécologie, Obstétrique, Fertilité Sénologie 49:95–96

Asadi-Pooya AA, Cross JH (2020) Is wearing a face mask safe for people with epilepsy? Acta Neurol Scand. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.13316

Parrinello G, Missale F, Sampieri C, Carobbio ALC, Peretti G (2020) Safe management of laryngectomized patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oral Oncol 107:104742

Primov-Fever A, Amir O, Roziner I, Maoz-Segal R, Alon EE, Yakirevitch A (2021) How face masks influence the sinonasal quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino- Laryngol 27:1–7

Muzzi E, Chermaz C, Castro V, Zaninoni M, Saksida A, Orzan E (2021) Short report on the effects of SARS-CoV-2 face protective equipment on verbal communication. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 278(9):3565–3570

Marler H, Ditton A (2021) “I’m smiling back at you”: Exploring the impact of mask wearing on communication in healthcare. Int J Lang Commun Disord 56(1):205–214

West JS, Franck KH, Welling DB (2020) Providing health care to patients with hearing loss during COVID-19 and physical distancing. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 5(3):396–398. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.382

Greenhalgh T, Schmid MB, Czypionka T, Bassler D, Gruer L (2020) Face masks for the public during the COVID- 19 crisis. BMJ 369:m1435. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1435

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights statement and Informed consent

For our research any Ethical Statements/informed consent aren't avaible because is a review of orginal articles and not an experimental study involving human or animals.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Balestracci, B., La Regina, M., Di Sessa, D. et al. Patient safety implications of wearing a face mask for prevention in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and consensus recommendations. Intern Emerg Med 18, 275–296 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-022-03083-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-022-03083-w