Abstract

Since the pioneering study of Le Roy Ladurie and his team, the idea that mean height can be considered as a reliable indicator of the standard of living has emerged from a long debate among historians and economists. Considering height in this respect, nineteenth-century France, unlike most Western countries, did not pay an urban penalty. Thanks to a substantial set of individual data (105,324 observations), based on the draft lottery of Frenchmen born in the year 1848, we are able to prove that this “French exception” did not, in fact, exist. The larger the town, the shorter were the conscripts. Among the towns, Paris had the shortest conscripts. By combining individual data with the agricultural survey of 1852, we are able to identify those factors that compensated for this urban penalty—that were positively correlated with height: nutritional availability, the literacy rate, and life expectancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A French department is roughly the size of a county.

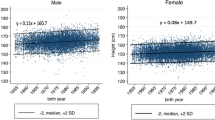

We accept the definition of “stunted” found in Postel-Vinay and Sahn (2010), since this figure is considered generally valid. It corresponds to conscripts “whose heights were less than or equal to 1.6247 m, which corresponds to -2 standard deviation scores of the WHO growth standards.”

The percentage of the French population living in a town or city (defined as an agglomeration of 2,000 or more persons) increased from 25.5 % in 1851 to 34.8 % in 1881 and then to 41 % in 1901 (Bourillon 1992).

Komlos reaches the same conclusion regarding the socio-economically privileged students of the Ecole Polytechnique (Komlos 1993). It is therefore extremely likely that the reasons for this decline were epidemiological and affected the entire urban population (conscripts and students), rather than nutritional, the effect of which would have been in indirect proportion to one’s socio-economic level and thus would have had a greater impact on conscripts than on students.

Demonet (1990). Nineteen percent of all foodstuffs were marketed outside the district in which they were produced, and wheat constituted more than a third of such non-local commerce.

Mean height birth cohorts 1838–1847: 164.7 cm; mean height birth cohort 1848: 164.7 cm (Weir 1997).

For those who could be considered among the shortest in France (Saint-Yrieix and Bellac districts, department of Haute-Vienne, Limousin), the century minimum is not reached with the 1848 birth cohort but with that of 1826; as for the tallest (Melun district, department of Seine-et-Marne, Ile-de-France), the century maximum is reached in 1856, after three decades of growth, whereas for Mulhouse (department of Haut-Rhin, Alsace), the only urban area included in this regional analysis, height declined during the first half of the century and did not touch bottom until 1859 (Heyberger 2005).

See Table 1. Other variables have been incorporated into models that are not included here for lack of satisfactory results: the annual number of work hours attributable to child labor, the extent of the migration of agricultural workers between districts, and various estimates of agricultural wages (whether real or nominal). It is surprising that there are no definitive results regarding wages, since their impact has been convincingly demonstrated at the departmental level (Weir 1997; Postel-Vinay and Sahn 2010). One possible explanation is that agricultural wages increased significantly during the reign of Napoleon III, benefiting members of the 1848 birth cohort shortly before they were measured as part of the conscription process, and thus blurring the height-wages correlation that might have been evident in 1852, when the conscripts were just toddlers. It is unfortunate that the agricultural surveys undertaken during the 1860s do not provide district-level wage data, which would have permitted us to test this hypothesis. Moreover, it is important to bear in mind that our analysis of the relation between height and agricultural wages is based on a more local division (France counts 363 districts spread among 86 departments), capable of generating different results, than has previously been used. The proportion of agricultural workers varies considerably from one district to another; in fact, it is nonexistent or nearly so in a number of districts despite their being essentially rural. The composition of the active population is thus too complex and varied at the district level for the wages of a given category of workers to have a significant impact on individual height. For the same reason, even though the regressions conducted at the individual level (the endogenous variable being individual height) demonstrate the importance of the job structure as a factor in the anthropometric disparities that we observe, the introduction of job-category variables into the regressions conducted at the aggregated level (the endogenous variable being mean height per district) does not provide an explanation of those disparities. In fact, the two categories that not only are the most populous but also compose the shortest mean-height category (agricultural and textile workers) constitute such a small proportion of the total that their introduction as a poverty-level marker does not improve the models’ capacity to explain the situation.

We have given priority to the methodology and hypotheses of Demonet (1990) since they are more plausible than those of Toutain (1971), but we turned to the latter whenever Demonet’s seemed to overestimate or underestimate some figures in comparison with what is usually used in international standard consumption studies. For a detailed presentation of the methodology adopted for the conversion of the agricultural-survey data into nutritional availability, see Heyberger (2009).

By the nineteenth century, Paris was already the largest city in France. The 1851 census numbered the city’s population at more than a million, far ahead of second-place Marseille, at only 195,257 (Le Mée 1989).

For France taken as a whole, potatoes furnished a daily supply of only 86 calories per capita but our sample includes 6 of the 10 departments where the per capita rate was the highest (150 calories and above: Hautes-Alpes, Aveyron, Moselle, Bas-Rhin, Haute-Vienne and Vosges). All of the production-based estimates exclude animal consumption when necessary. The calculation of the entire collection of estimations (whether they are based on production or consumption figures) takes into account losses due to storage and transport and includes only edible parts of foodstuffs.

Husson (1856). In converting Husson’s food-consumption data into nutritional intake, we respect both his hypothesis (in regard to the proportion of those who purchased their food at markets in and around Paris—with the exception of certain categories, such as hospitals and military units—black-market transactions both extra and intra muros, etc.) and the methodology used in the agricultural survey.

They are preserved in the series R of the departmental archives, located in the prefecture of each department.

See Table 2. For a complete presentation of this type of source, see Heyberger (2005). The French administrative units are, from smallest to largest, the commune, the canton, the district, and the department; thus, canton-level data provide a high degree of material detail and hence permit an equally high degree of analytical accuracy.

Because we lack data permitting us to calculate nutritional availability on a scale smaller than that of the commune, the urban districts of large cities are combined into one. In selecting the 134 districts, we rejected those whose registers included height data for fewer than 100 conscripts—certain registers being incomplete or even blank, on account of bureaucratic negligence—and those in which the distribution of height below the mean was not normal. (The fact that heights below the military’s minimum of 155 cm were not always recorded goes far to explain the small size of certain standard deviations.) It is necessary to impose these selection criteria if one intends to compare the pattern of average height with that of the stunted percentage in regressions that, for the same reason, also have to display exactly the same explanatory variables and N of endogenous variables. In addition, we eliminated one district in which the conscripts’ educational level could not be determined, since without this information, we could not calculate the literacy rate, a figure needed for the aggregate-level regressions.

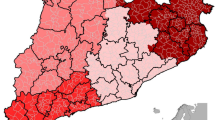

The 35 student volunteers who helped me to collect the data, between 2004 and 2008, did so in departments of their own choosing, based on their geographical origins or family ties. I myself collected data in 10 departments (Bouches-du-Rhône, Corrèze, Creuse, Loire-Inférieure, Maine-et-Loire, Moselle, Bas-Rhin, Haut-Rhin, Seine-et-Marne, and Haute-Vienne).

Standard deviation: 6.43 cm.

Weir’s data are not published at the departmental level.

See footnote 19.

The legal threshold, being much lower (2,000), does not permit this. See Pinol and Walter (2003); the entirety of Bairoch’s work since 1985; and Baten and Murray (2000). As for the upper threshold, we kept it at 75,000 so that we could categorize Lille (pop. 75,795) as a large city. The other threshold (20,000) was chosen in order to obtain an even size distribution of the various classes. In regard to the impact of these thresholds on the results, see also the next note.

Because the urbanization rate in many of the cantons, and even in 29 of the districts, is at zero—a figure that cannot be converted into a decimal logarithm—we have used scaled-down samples to test the impact of urbanization, expressed as the urbanization rate and its logarithm; in both cases, the sign associated with the coefficient of the urbanization variable remains the same as the one that is observed when the urbanization variable is expressed in a discontinuous form. In the interests of brevity, we do not present the results in this paper.

The breadth and depth of our sample—comprising as it does 5 of the 9 French cities with populations over 75,000 (in order of diminishing size: Paris, Marseille, Lyon, Rouen, Lille), numerous moderate-size ones (e.g., Aix-en-Provence, Montpellier, Amiens, Brest, and Limoges), and a raft of smaller ones, including Beaune, Fontainebleau, Gap, Nevers, and Saumur—goes far to ensure the reliability of our results regarding the influence of the urban milieu on height. In fact, the cities are markedly over-represented, since in 1851, the urbanization rate (using the population threshold of 5,000) of the 134 districts is 35.5%, whereas the national average (using the legal population threshold: 2,000) is only 25.5%.

Between 1852 and 1869, the number of railway passengers increased eightfold, the quantity of freight more than 12-fold.

There is no correlation between the Bonneuil and the Lebras and Todd figures (R 2 = 0,00). Thanks go to Jean-Pierre Bardet for his comments concerning these demographic figures. Paris was the only large city burdened with an urban penalty, if one uses the infant-mortality rate as the indicator (Seine: 456), whereas Lyon (Rhône: 209) boasted a mortality rate below the average of the sample (210.55).

Female residents of Paris (Seine) and Lyon (Rhône) had a life expectancy at birth of 30.9 and 33.1 years, whereas during the period 1846–1850, the average for the departments in our sample was 40.1 years (Bonneuil 1997). Over the long run, height is closely correlated with both life expectancy and mortality, which in turn are very closely correlated with infant mortality (Komlos 1998; see also the following studies for evidence of this correlation in particular countries: Horlings and Smits (1997) (the Netherlands), Weir (1997) (France), and Haines (1998) (US).

Moreover, this job gap widens when one controls these correlations for the “department of residence” variables (Table 5). Among the 4 groups for which there is more than 1 cm of height loss in Table 5 relative to Table 4, 3 are found in those associated with the Industrial Revolution (industry, mining, and textile)—a finding in line with the fact that these job groups (along with the fourth group, farm-workers) were found in the northern and most prosperous region of France.

The draft-lottery lists provide information concerning a given job sector but rarely any information concerning the status.

Regressions are not reported in Table 4. All of the respective coefficients are significant (0.1 %): 0.06, 0.002, and 0.03. All of the other coefficients of the regression remained practically unchanged.

0.06–0.11 francs (price of transport) for 400 g of milk, as opposed to 0.07 francs for 90 g of beef.

Our results were similar when we used the reduced sample of 81,605 individual observations (without Paris, see Heyberger 2009). In this regard, the hypothesis that a heavy penalty was imposed on Paris seems all the more plausible, even if the food-availability estimates for Paris derive from Husson and not from the agricultural survey. Moreover, while the estimates of animal-protein availability for the big cities are based on the latter, the urban penalty also increases here.

Once again, small towns are the exception. The urban penalty reaches 0.6 cm for medium-size cities and more than 1 cm for large ones—with the exception of Paris, where it reaches nearly 3 cm.

This figure seems quite large; Baten and Komlos—no doubt on the basis of other, unspecified hypotheses—claim that the life-expectancy increase correlated with a 1-cm height increase is only 1.2 years in length (Baten and Komlos 1998). In contrast, extrapolating from our results, one would conclude that over the course of the Industrial Revolution, life expectancy increased by more than one hundred years! Nevertheless, diachronic data lend plausibility to our calculation, at least in the case of nineteenth-century France: an increase in conscripts’ mean height of 0.75 cm between the 1790–1799 and the 1820–1829 birth cohorts is paralleled by a 7.2-year increase in female life expectancy.

See footnote 12.

It is here that the “ecological fallacy” comes into play: the district constitutes an ecological unit far too large to permit one to identify with any precision the impact of noticeable, significant factors that play a role at the cantonal level.

All of the regressions are statistically significant at the 1 % level. The R 2 of the regressions between mean height and, respectively, protein, animal-protein, and calcium consumption, CNI, and life expectancy is, respectively, 0.10, 0.26, 0.26, 0.20, and 0.28. Respective values for the regressions with the proportion of stunted individuals as the endogenous variable are 0.10, 0.23, 0.22, 0.18, and 0.31. Moreover, the correlation between the mean height and the stunted proportion is very strong (R 2 = 0.96).

Regressions with stunted proportion of conscripts as endogenous variable are not reported here since the results are very close to those obtained with mean height (R 2 of models 1–3 of Table 6 with stunted proportion as endogenous variable: 0.52; 0.56; 0.60, all significant at the 0.1% level). This phenomenon is due to the very strong correlation between these two endogenous variables (see previous note).

In Table 6, the nutritional variable that we chose to use is the availability of animal protein rather than of calcium, even though the R 2s of the regressions calculated with a single explanatory factor are similar for the two (see footnote 42). In fact, the value of the coefficients associated with animal-protein availability is greater in the case of mean height as well as that of the proportion of stunted individuals, and we have already seen that at the individual level, animal protein (meat and milk) seems to posses a greater explanatory capacity than does milk alone.

References

A’Hearn B (2003) Anthropometric evidence on living standards in northern Italy, 1730–1860. J Econ Hist 63(2):351–381

A’Hearn B, Perrachi F, Vecchi G (2009) Height and the normal distribution: evidence from Italian military data. Demography 46(1):1–25

Ambadekar NN, Wahab SN, Zodpey SP et al (1999) Effect of child labour on growth of children. Pub Health 113:303–306

Aron J-P, Dumont P, Le Roy Ladurie E (1972) Anthropologie du conscrit français d’après les comptes numériques et sommaires du recrutement de l’armée 1819–1826. Mouton, Paris

Bassino J-P, Dormois J-P (2009) Comment tenir compte des erreurs de mesure dans l’estimation de la stature des conscrits français? Hist Econ et Soc 28(1):97–122

Baten J (1999a) Ernährung und wirtschaftliche Entwicklung in Bayern (1730–1880). Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart

Baten J (1999b) Kartographische residuenanalyse am beispiel der regionalökonomischen lebensstandardforschung über baden, Württemberg und Frankreich. In: Ebeling D (ed) Historisch-thematische Kartographie. Konzepte-Methoden-Anwendungen. Vg. für Regionalgeschichte, Bielefeld, pp 98–109

Baten J (2009) Protein supply and nutritional status in nineteenth century Bavaria Prussia and France. Econ Hum Biol 7(2):165–180

Baten J, Komlos J (1998) Height and the standard of living. J Econ Hist 57(3):866–870

Baten J, Komlos J (2004) Looking backward and looking forward. Anthropometric research and the development of social science history. Soc Sci Hist 28(2):191–210

Baten J, Murray J (2000) Heights of men and women in nineteenth-century bavaria: economic, national, and disease influences. Explor Econ Hist 37(4):351–369

Beaugrand E (1874) Chemin de fer. In: Dechambre A (ed) Dictionnaire encyclopédique des sciences médicales. Paris: Masson et Asselin, première série, t. 15, 683–708

Boëtsch G, Brus A, Ancel B (2008) Stature, economy and migration during the nineteenth century: comparative analysis of Haute-Vienne and Hautes-Alpes France. Econ Hum Biol 6(1):170–180

Bogin B (1999) The growth of humanity. Wiley-Liss, New York

Bonnain-Moerdijk R (1975) L’alimentation paysanne en France entre 1850 et 1936. Etudes rural 58:29–49

Bonneuil N (1997) Transformation of the French demographic landscape 1806–1906. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Bourillon F (1992) Les Villes en France au XIXe siècle. Ophrys, Paris

Brown JC, Guinnane TW (2007) Regions and Time in the European Fertility Transition: Problems in the Princeton Project’s Statistical Methodology. Econ Hist Rev 60(3):574–595

Chanda A, Craig L, Treme J (2008) Convergence (and divergence) in the biologicals standard of living in the United States, 1820–1900. Cliometrica 2(1):19–48

Cinnirella F (2008) On the road to industrialization: nutritional status in saxony, 1690–1850. Cliometrica 2(3):229–257

Cranfield J, Inwood K (2007) The great transformation: a long-run perspective on physical well-being in Canada. Econ Hum Biol 5(2):204–228

Demonet M (1990) Tableau de l’agriculture Française au milieu du 19e siècle. L’enquête de 1852. Editions de l’EHESS, Paris

Désert G (1975) Viande et poisson dans l’alimentation des Français au milieu du XIXe siècle. Ann Econ Soc Civilis 30:519–536

Duclos J-Y, Leblanc J, Sahn DE (2011) Comparing population distributions from bin-aggregated sample data: an application to historical height data from France. Econ Hum Biol 9(4):419–437

Dupâquier J, Pélissier J-P (1992) Mutation d’une société: la mobilité professionnelle. In: Dupâquier J, Kessler D (eds) La Société française au XIXe siècle. Tradition, transition, transformations. Fayard, Paris, pp 121–179

Dupin C (1827) Forces productives et commerciales de la France. Bachelier, Paris

Floud R, Wachter K, Gregory A (1990, reprint: 2004) Height, health and history. Nutritional status in the United Kingdom, 1750–1980. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Grantham G (1995) Food rations in France in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century: a reply. Econ Hist Rev 48:774–777

Grantham G (1997) Espaces privilégiés: productivité agraire et zone d’approvisionnement des villes dans l’Europe préindustrielle. Ann Hist Sci Soc 52(3):695–715

Haines M (1998) Health, height nutrition and mortality: evidence on the ‹Antebellum Puzzle› from Union Army Recruits for New York State and the United States. In: Komlos J, Baten J (eds) The biological standard of living in comparative perspective. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 155–180

Haines M, Craig L, Weiss T (2003) The short and the dead: nutrition, mortality, and the ‹Antebellum Puzzle› in the United States. J Econ Hist 63(2):382–413

Heyberger L (2005) La Révolution des corps. Décroissance et croissance staturale des habitants des villes et des campagnes en France, 1780–1940. Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg and Pôle Editorial Multimédia UTBM, Strasbourg and Belfort

Heyberger L (2007) Toward an anthropometric history of provincial France, 1780–1920. Econ Hum Biol 5(2):229–254

Heyberger L (2008) Approche par l’histoire anthropométrique de l’évolution des niveaux de vie à Belfort et à Mulhouse durant la révolution industrielle (1796–1940). Bull Soc belfortaine d’émulation 99:37–52

Heyberger L (2009) Niveaux de vie biologiques, disponibilités alimentaires et consommations populaires en France au milieu du XIXe siècle. Ann demogr hist, 167–191

Horlings E, Smits J-P (1997) The quality of Life in the Netherlands 1800–1913. Experiments in measurement and aggregation. In: Komlos J, Baten J (eds) The biological standard of living in comparative perspective. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 321–343

Humphries J, Leunig T (2009) Was Dick Whittington taller than those he left behind? Anthropometric measures, migrations and the quality of life in early nineteenth century London. Explor Econ Hist 46(1):120–131

Husson A (1856) Les consommations de Paris. Guillaumin, Paris

Kirby P (1995) Causes of short stature among coal-mining children, 1823–1850. Econ Hist Rev 48(4):687–699

Koch D, Schubert H (2011) Anthropometric history of the French revolution in the province of Orléans. Econ Hum Biol 9(3):277–283

Komlos J (1993) The nutritional status of French students. J Interdiscip Hist 24:493–508

Komlos J (1995) De l’importance de l’histoire anthropométrique. Ann demogr hist, 211–223

Komlos J (1998) Shrinking in a growing economy? The mystery of physical stature during the industrial revolution. J Econ Hist 58(3):779–802

Komlos J (2003) Histoire anthropométrique: bilan de deux décennies de recherche. Econ Soc Ser Hist Econ Quant AF 29:1–24

Komlos J (2004) How to (and how not to) analyse historical heights samples. Hist Methods 37(4):160–173

Laurent R (1978) Les variations départementales du prix du froment en France (1801–1870). In: Centre Pierre Léon (ed) Histoire, économies, sociétés. Journées d’études en l’honneur de Pierre Léon (6–7 mai 1977). Presses universitaires de Lyon, Lyon

Le Bras H, Todd E (1981) L’invention de la France. Atlas anthropologique et politique. Le livre de poche, Paris

Le Mée R (1989) Les villes de France et leur population de 1806 à 1851. Ann demogr hist, 321–93

Malte Brun VA (1881–1884, 5 volumes) La France illustrée. Géographie-Histoire-Administration-Statistique. Jules Rouff, Paris

Margairaz D (1982) Les Dénivellations interrégionales des prix du froment en France, 1756–1870. Dissertation, Université de Paris I

Martínez Carrión J-M, Moreno-Lázaro J (2007) Was there an urban penalty in Spain, 1840–1913? Econ Hum Biol 5(1):144–164

Meyer HE, Selmer R (1999) Income, educational level and body height. Ann Hum Biol 26(3):219–227

Ministère de l’agriculture, du commerce et des travaux publics (1858 and 1860, 2 volumes) Statistique de la France Deuxième série. Statistique agricole. Imprimerie impériale, Paris

Morineau M (1971) Les Faux-Semblants d’un démarrage économique: agriculture et démographie en France au XVIIIe siècle. Armand Colin, Paris

Morineau M (1972) Budgets populaires en France au XVIIIe siècle. Revue Hist Econ Soc, 203–237 and 449–481

Morineau M (1974) Révolution agricole, révolution alimentaire, révolution démographique. Ann demogr hist, 335–371

Ó’Gráda C (1996) Anthropometric history: what’s in for Ireland? Hist mesure 11:139–166

Persson KG, Ejrnæs M (2000) Market integration and transports costs in France 1825–1903: a threshold error correction approach to the law of one price. Explor Econ Hist 37(2):149–173

Pinol J-L, Walter F (2003) La ville contemporaine jusqu’à la seconde guerre mondiale. In: Pinol J-L (ed) Histoire de l’Europe urbaine II De l’Ancien Régime à nos jours. Seuil, Paris, pp 11–275

Postel-Vinay G, Robin J-M (1992) Eating, working and saving in an unstable world: consumers in nineteenth-century France. Econ Hist Rev 45:494–513

Postel-Vinay G, Sahn D (2010) Explaining stunting in nineteenth-century France. Econ Hist Rev 63:315–334

Renouard D (1960) Les Transports de marchandises par fer, route et eau depuis 1850. Armand colin and fondation nationale des sciences politiques, Paris

Riley J (1994) Height, nutrition, and mortality risk reconsidered. J Interdiscip Hist 24(3):465–492

Solakoglu E (2007) The net effect of railroads on stature in the postbellum period. Res Econ Hist 24:105–117

Soudjian G (2008) Anthropologie du conscrit parisien sous le second empire. Lavauzelle, Panazol

Steckel RH (1998) Strategic ideas in the rise of the new anthropometric history and their implications for interdisciplinary research. J Econ Hist 58(3):803–821

Steckel RH (2009) Heights and human welfare: recent developments and new directions. Explor Econ Hist 46(1):1–23

Steckel RH, Floud R (1997) Conclusions. In: Steckel RH, Floud R (eds) Health and welfare during industrialization. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 423–449

Tanner JM (1994) Introduction: growth in height as a mirror of the standard of living. In: Komlos J (ed) Stature, living standards, and economic development. Essays in anthropometric history. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 1–6

Toutain J-C (1971) La consommation alimentaire en France de 1789 à 1964. Econ Soc Ser Econ Quant 5(9):1909–2049

Van Meerten M (1990) Développement économique et stature en France XIXe–XXe siècles. Ann Econ Soc Civilis 45(3):755–778

Weir D (1993) Parental consumption decisions and child health during the early French fertility decline, 1790–1914. J Econ Hist 53:259–274

Weir D (1997) Economic welfare and physical well-being in France, 1750–1990. In: Steckel RH, Floud R (eds) Health and welfare during industrialization. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 161–200

Whitwell G, de Souza C, Nicholas S (1997) Height, health and economic growth in Australia, 1860–1940. In: Steckel RH, Floud R (eds) Health and welfare during industrialization. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 379–422

Acknowledgments

This study has benefited from the financial support of the French–Japanese Chorus Project, on the standard of living in France and Japan (2004–2008). I would like to thank all of the participants in this program for their comments and suggestions, and especially Jean-Pierre Dormois, along with the members of the workshop on the standard of living in France and Spain organized by the AEHE (Asociación española de historia económica) and the AFHE (Association française d’histoire économique) (Aix, 2008) and the two anonymous reviewers of Cliometrica. Thanks also go to Professor John Komlos for his help and encouragement and the auditors of the Nuffield College workshop on economic history (2008) and of the Sorbonne seminar on demographic history (2011), for their contribution to the refining of certain hypotheses. I also owe a great debt of gratitude to the students in engineering at the UTBM, who devoted considerable time and effort to the collection of individual data from the 1868 draft lottery, recorded in departmental lists; my deepest thanks to them all. Last but not least, I am most grateful to Guy Soudjian for his kindness in providing me with his data on the department of the Sarthe. A first draft of this study, based on a limited data sample, of 81,065 observations (that is, excluding the Paris ones), appeared in Los Niveles de vida en España y Francia (siglos XVIII–XX), under the direction of G. Chastagneret, J.-C. Daumas, A. Escudero, and O. Raveux (Alicante: Publicationes de la Universidad de Alicante, Publications de l’Université de Provence, 2010), 301–16, and in Annales de démographie historique, 2009: 2, 167–91.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Heyberger, L. Received wisdom versus reality: height, nutrition, and urbanization in mid-nineteenth-century France. Cliometrica 8, 115–140 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-013-0095-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-013-0095-1