Abstract

Background

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is commonly used in the screening and evaluation process with bariatric surgery candidates despite relatively limited psychometric evidence in this patient group. We examined the validity of the BDI and its clinical utility for subtyping women seeking gastric bypass surgery.

Methods

One hundred twenty-four women evaluated for gastric bypass surgery were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P) and completed a self-report battery of psychosocial measures including the BDI.

Results

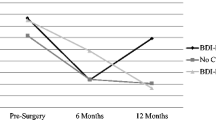

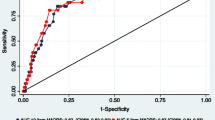

Based on the SCID-I/P, 12.9 % (n = 16) met criteria for current mood disorder. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis revealed the BDI had a good area under the curve (0.788) for predicting SCID-I/P mood disorder diagnosis; BDI score of >15 optimized both sensitivity and specificity. Patients diagnosed with SCID-I/P mood disorders had significantly higher levels of eating disorder psychopathology, self-esteem, and shame, than those without mood disorders. Based on a BDI cut-off score of >15, 41.9 % (n = 52) were categorized as high-BDI and 58.1 % (n = 72) as low-BDI. Patients characterized as high-BDI also had significantly higher levels of all associated measures than those with low-BDI; effect sizes for the differences by BDI subtyping were generally 2–3 times greater than those observed when comparing SCID-I/P-based mood versus no mood disorder subgroups.

Conclusions

In women seeking gastric bypass surgery, the BDI demonstrated limited acceptability efficiency for identifying mood disorders with a cut-point score of >15. When identifying clinical severity, however, subtyping women by BDI scores of >15 may identify a significantly more disturbed subgroup than relying on a SCID-I/P-generated mood disorder diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient—013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(2):337–72.

Bauchowitz AU, Gonder-Frederick LA, Olbrisch ME, et al. Psychosocial evaluation of bariatric surgery candidates: a survey of present practices. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:825–32.

Fabricatore AN, Crerand CE, Wadden TA, et al. How do mental health professionals evaluate candidates for bariatric surgery? Survey results. Obes Surg. 2006;16(5):567–73.

Ayloo S, Thompson K, Choudhury N, et al. Correlation between the Beck Depression Inventory and bariatric surgical procedures. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(3):637–42.

Hall BJ, Hood MM, Nackers LM, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in bariatric surgery candidates. Psychol Assess. 2013;25(1):294–9.

Hayes S, Stoeckel N, Napolitano MA, et al. Examination of the Beck Depression Inventory-II factor structure among bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. 2015;25(7):1155–60.

Krukowski RA, Friedman KE, Applegate KL. The utility of the Beck Depression Inventory in a bariatric surgery population. Obes Surg. 2010;20(4):426–31.

Hayden MJ, Brown WA, Brennan L, et al. Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory as a screening tool for a clinical mood disorder in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. 2012;22(11):1666–75.

Wang YP, Gorenstein C. Assessment of depression in medical patients: a systematic review of the utility of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Clinics. 2013;68(9):1274–87.

Gagnon-Girouard MP, Begin C, Provencher V, et al. Subtyping weight-preoccupied overweight/obese women along restraint and negative affect. Appetite. 2010;55(3):742–5.

Jansen A, Havermans R, Nederkoorn C, et al. Jolly fat or sad fat? Subtyping non-eating disordered overweight and obesity along an affect dimension. Appetite. 2008;51(3):635–40.

Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Crosby RD. Predictors and moderators of response to cognitive behavioral therapy and medication for the treatment of binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):897–906.

Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Subtyping binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(6):1066–72.

Beck AT, Steer R. Manual for revised Beck Depression Inventory. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1987.

Walfish S, Vance D, Fabricatore AN. Psychological evaluation of bariatric surgery applicants: procedures and reasons for delay or denial of surgery. Obes Surg. 2007;17(12):1578–83.

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:363–70.

Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder: a replication. Obes Res. 2001;9(7):418–22.

Cooper PJ, Taylor MJ, Cooper Z, et al. The development and validation of the body shape questionnaire. Int J Eat Disord. 1987;6(4):485–94.

Rosenberg M. Conceiving the Self. New York: Basic Books; 1979.

Cook DR. Measuring shame: the internalized shame scale. Alcohol Treat Quart. 1988;4(2):197–215.

Cook DR. The Internalized Shame Scale Professional Manual. Menomenie: Channel Press; 1990.

Mahony D. Psychological gender differences in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. 2008;18(5):607–10.

Ambwani AG, Boeka AG, Brown JD, et al. Socially desirable responding by bariatric surgery candidates during psychological assessment. SOARD. 2013;9(2):300–5.

Fabricatore AN, Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, et al. Impression management or real change? Reports of depressive symptoms before and after the preoperative psychological evaluation for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2007;17(9):1213–9.

Corsica JA, Azarbad L, McGill K, et al. The personality assessment inventory: clinical utility, psychometric properties, and normative data for bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. 2010;20(6):722–31.

White MA, Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, et al. Prognostic significance of depressive symptoms on weight loss and psychosocial outcomes following gastric bypass surgery: a prospective 24-month follow-up study. Obes Surg. 2015. Epub ahead of print 2015 Feb 27

Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8(1):77–100.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Grilo was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K24 DK070052, R01 DK098492). Dr. Barnes was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K23 DK092279). No additional funding was received for the completion of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Ivezaj declares that there is no conflict of interest. Dr. Barnes reports grants from NIDDK. Dr. Grilo reports no relevant conflicts of interest with respect to this work but more generally reports that he has received grants from the National Institutes of Health, consulting fees from Shire and Sunovion, honoraria from the American Psychological Association and from universities and scientific conferences for grand rounds and lecture presentations, speaking fees for various CME activities, consulting fees from American Academy of CME, Vindico Medical Education CME, and General Medical Education CME, and book royalties from Guilford Press and from Taylor Francis Publishers.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ivezaj, V., Barnes, R.D. & Grilo, C.M. Validity and Clinical Utility of Subtyping by the Beck Depression Inventory in Women Seeking Gastric Bypass Surgery. OBES SURG 26, 2068–2073 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2047-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2047-x