Abstract

Over the last 2 decades, it has become increasingly evident that incremental adaptation to global environmental challenges—particularly climate change—no longer suffices. To make matters worse, systemic problems such as social inequity and unsustainable use of resources prove to be persistent. These challenges call for, such is the rationale, significant and radical systemic changes that challenge incumbent structures. Remarkably, scholarship on sustainability transformations has only engaged with the role of power dynamics and shifts in a limited fashion. This paper responds to a need for methods that support the creation of imaginative transformation pathways while attending to the roles that power shifts play in transformations. To do this, we extended the “Seeds of Good Anthropocenes” approach, incorporating questions derived from scholarship on power into the methodology. Our ‘Disruptive Seeds’ approach focuses on niche practices that actively challenge unsustainable incumbent actors and institutions. We tested this novel approach in a series of participatory pilot workshops. Generally, the approach shows great potential as it facilitates explicit discussion about the way power shifts may unfold in transformations. It is a strong example of the value of mixing disciplinary perspectives to create new forms of scenario thinking—following the call for more integrated work on anticipatory governance that combines futures thinking with social and political science research into governance and power. Specifically, the questions about power shifts in transformations used in this paper to adapt the Seeds approach can also be used to adapt other future methods that similarly lack a focus on power shifts—for instance, explorative scenarios, classic back-casting approaches, and simulation gaming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, it has become increasingly evident that incremental adaptation to global environmental challenges—particularly climate change—no longer suffices (Jackson 2009; Ribot 2011; Westley et al. 2011; IPCC 2021). To make matters worse, systemic problems such as social inequity and unsustainable use of resources prove to be persistent (Hölscher et al. 2018). These challenges call for, such is the rationale, significant and radical systemic changes that challenge incumbent structures (Olsson et al. 2014; Blythe et al. 2018)—or as Head (2019:ix) put it: it is “widely recognized we need to shift some very big cultural frames—the importance of economic growth, the dominance of fossil fuel capitalism, the hope of modernity as an unending process—to deal adequately with climate change.” Such transformations necessarily involve questioning the deep social and physical structures of current civilization as well as entrenched patterns of daily life (Jasanoff et al. 2013). Transformations have been framed in a number of ways—examples include transition approaches, social–ecological transformations, and sustainability pathways (Feola et al. 2021). However, remarkably, scholarship on sustainability transformations has only engaged with the role of power dynamics and shifts in a limited fashion (Avelino 2017), even though it has been argued that power shifts are fundamental to transformations (Stirling 2015; Avelino and Wittmayer 2016). Following Avelino (2011, 2017), we define power dynamics as the way in which different forms of power interact—one form of power may enable or enforce another form of power (a synergetic power dynamic), or oppositely, one form of power can resist or disrupt another form of power (an antagonistic power dynamic) (Avelino 2011, 2017). Following Avelino (2017) and Brisbois (2019), we define power shifts as follows: power shifts happen when the position of incumbent actors, or the current regime, is opposed by actors who challenge their power and eventually replace them.

Scenarios can be used as a tool to explore how transformations might unfold in the future, and they can help to guide decision-making processes. However, scenarios are more often used to explore future uncertainties (what might happen?) rather than to explicitly imagine desirable transformations (what should happen?) (Muiderman et al. 2020). When they do explore transformative visions, they often fail to explicitly address the political aspects of transformations. Scenarios are often not explicitly designed to explore and interrogate the role of power in transformations (Rutting et al. 2022). We argue that there is a need for a politically explicit scenario approach focused on the exploration of power shifts in sustainability transformations, which allows for more ambitious, transformative decision-making and planning.

To achieve this, we build on a new scenario approach that engages with transformations developed by Bennett et al. (2016), who contend that our thinking about the future is currently dominated by either dystopian or utopian visions, and by business-as-usual projections (Bennett et al. 2016). Moreover, existing global scenarios are often based on simplified worldviews (Bennett et al. 2016) and do not take account of the plurality of societal imaginaries that exist between and within regions (Rutting et al. 2022). Bennett et al. (2016) argue that there is a need for a novel approach to thinking about the future, which emphasizes “hopeful” elements and focuses on initiatives that fundamentally challenge current unsustainable structures and practices, to generate creative, bottom-up scenarios. In response, they developed an approach—“Seeds of Good Anthropocenes”—based on niches, good practices, and experiments that represent sustainable alternatives to the unsustainable status quo (Bennett et al. 2016). Such niches are called “seeds” and can be defined as “initiatives (social, technological, economic, or social–ecological ways of thinking or doing) that exist, at least in prototype form, and that represent a diversity of worldviews, values, and regions, but are not currently dominant in the world” (Bennett et al. 2016:442) and “real-world agents of current social-ecological transformation that are currently marginal, but have the potential to grow in impact” (Raudsepp-Hearne et al. 2019:606). This approach offers a novel way of bottom-up transformative scenario development inspired by real-world initiatives (Bennett et al. 2016; Pereira et al. 2021).

However, this Seeds approach still lacks an explicit focus on political change and power shifts. Raudsepp-Hearne et al. (2019) report on a case where the Seeds approach was used, and among their conclusions, they articulated the need for a stronger focus on radical transformations—they argue that the involvement of activists and change-makers can enhance the potential of the Seeds approach. Reasoning further along these lines, we argue that in order to better harness the potential of the Seeds approach to imagine sustainability transformations, there is a need to focus on seeds that actively challenge the unsustainable status quo. Examples of such seed practices that directly challenge existing power structures might include the law suit filed by the Urgenda Foundation against the Dutch state, who are failing to meet the carbon emission reduction targets set by the IPCC (The Guardian 2018), and court cases against multinational fossil fuel companies Shell, ExxonMobil and Chevron (ABC News 2021). Other examples include divestment from fossil fuel by pension funds (for example, ABP; see The Guardian 2021), energy cooperatives, and disruptive initiatives such as Ende Gelände, a German movement that actively challenges and hinders coal extraction to raise awareness for climate justice (Ende Gelände n.d.).

In this paper, we aim to link the concepts of seeds and transformation to power dynamics. The objective of this paper is to further develop the Seeds approach and make it better attuned to explicitly exploring power dynamics and shifts. To this end, we introduce the Disruptive Seeds approach. We define Disruptive Seeds as seeds of transformative change (i.e., niche initiatives or practices) that exist—at least in prototype form—and are currently marginal, but have the potential to grow in impact through actively challenging (disrupting) currently dominant but unsustainable, incumbent systems and associated actors. We explore how and to what extent this novel approach enhances the imagination of transformative futures, and if and how it allows for a more explicit description and understanding of power dynamics between actors and power shifts in transformations. As part of this methodological and conceptual innovation, we integrate important questions related to shifting power dynamics from key scholars into this updated approach. We also explored to what extent this novel approach allows for development of transformative scenarios in practice. To this end, we organized a number of participatory pilot workshops, which illustrate the potential of the Disruptive Seeds approach.

This paper contributes to the emerging literature on seeds (Bennett et al. 2016; Pereira et al. 2018a; Raudsepp-Hearne et al. 2019), both in terms of research agenda setting (exploring the transformative potential of the Seeds approach) and methodological innovation, by substantiating its implicit transformational potential with an explicit focus on power dynamics.

Theoretical framework

Here, we first describe the different ways in which sustainability transformations have been conceptualized in the literature, and discuss how the role of power in transformations has been addressed. Then, we introduce the “Seeds of Good Anthropocenes” approach (Bennett et al. 2016; Pereira et al. 2018a, b; Raudsepp-Hearne et al. 2019), in this paper referred to as simply “Seeds approach”, on which we build in this paper. This approach aims to explore, envision, or guide sustainability transformations, in order to develop “well-articulated pathways to a more positive future” (Bennett et al. 2016:441): it uses the Three Horizons model (Sharpe et al. 2016) as a simple multi-level model to visualize the trajectory of transformations. We specifically focus on how this approach can be strengthened in how it engages with power dynamics and power shifts. We do so by introducing a number of important insights from scholarship on the role of power in transitions which we integrated with Three Horizons. We argue that a scenario approach that allows for explicit exploration of power shifts in transformations can help formulation of more ambitious and transformational policies.

Transformations: definitions and criticisms

The terms transition and transformation are often used interchangeably, and there are many different and overlapping definitions. In response, different scholars have attempted to classify and distinguish the different concepts used in the literature (e.g., Feola 2015; Patterson et al. 2017). Feola found eight different definitions of transformation that are often employed, differing in terms of how systems are conceptualized, the level of social consciousness (i.e., whether transformations are deliberate or emergent), and outcome (which can be either prescriptive or descriptive) (Feola 2015). Similarly, Patterson et al. (2017) distinguish four conceptual approaches to transformations: (1) transition approaches, which assumes a multi-level perspective, i.e., niche, regime and landscape levels (Geels 2002; Geels and Schot 2007); (2) social–ecological transformations, that can be either deliberate (“purposefully navigated”) or emergent (“unintended”) (Chapin III et al. 2009:241), and in which transformability is defined as “the capacity to create a fundamentally new system when ecological, economic, or social (including political) conditions make the existing system untenable” (Walker et al. 2004:3); (3) sustainability pathways, an approach that aims to address complex sustainability problems from the perspectives of both research and governance, and emphasizes the inherent political character of transformations (Leach et al. 2010; Stirling 2015); and (4) transformative adaptation, which “seeks to instigate fundamental changes at a structural level of socio-technical-ecological systems” (Patterson et al. 2017:7).

However, several concerns have been voiced about current conceptualizations of transitions and transformations. Traditionally, sustainability transition studies have been criticized for insufficiently addressing the role of power and agency (Avelino 2017). This is striking, given the shifts in power that are, one could argue, inherent to transformations—or as Stirling put it: “perhaps history teaches us […] that the only sure way to achieve any kind of progressive social transformation is through unruly democratic struggle” (Stirling 2015:54). Similarly, scholars have raised concerns about the winners and losers of transformations—there is a risk of shifting the burden of transformation to vulnerable actors (Blythe et al. 2018). Furthermore, Feola et al. (2021) contend that current transformation discourse suffers from a number of additional shortcomings and knowledge gaps. They observe an innovation bias in many conceptualizations of transformations—and innovations, so they argue, do not necessarily challenge the status quo and vested, unsustainable interests. In fact, innovation is oftentimes very compatible with capitalist values as it potentially stimulates stock markets, for example (Feola et al. 2021). Generally, limited attention is paid to the role of current capitalist structures and associated imaginaries in transformations; deconstruction, disruption of, and liberation from capitalist imaginaries that assume and positively frame endless economic growth are often not part of the conversation (Feola et al. 2021). Furthermore, there is the risk of innovative practices and technologies being co-opted by status quo actors and used for greenwashing. In addition, similarly to Avelino’s critique on transition studies, Feola et al. (2021) state that there is “a lack of attention to power relations and the politics of sustainability transformations” (Feola et al. 2021:3). This can compromise its potential to resist current structures and the potential for conflict to trigger transformational processes. They, therefore, introduce the concept of “unmaking”, which refers to actively deconstructing modern capitalist imaginaries and social–ecological configurations to make space for radical alternatives that are not compatible with these capitalist structures (Feola 2019; Feola et al. 2021).

For conceptual clarity, we chose to build on the definitions of transition and transformation by Stirling (2015), Patterson et al. (2017) and Hölscher et al. (2018); we define transitions as “social, institutional and technological change in societal sub-systems” (Hölscher et al. 2018:2) that is “managed under orderly control, through incumbent structures” and geared “towards some particular known (presumptively shared) end” (Stirling 2015:54). We define transformations as a form of radical, complex, and dynamic change in social, political, cultural, institutional, technological, and ecological sub-systems (following Stirling 2015 and Patterson et al. 2017) which involves “more diverse, emergent and unruly political alignments, more about social innovations, challenging incumbent structures subject to incommensurable knowledges and pursuing (even unknown) ends” (Stirling 2015:54). That being said, we still use both terms in this paper when citing literature, as some scholars use ‘transformation’ and others ‘transition’ to refer to what we define as transformation.

Three Horizons and the Seeds approach

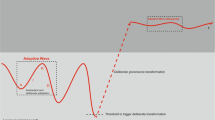

The Three Horizons model was developed by Sharpe et al. (2016) in response to the need for methods and practices that can help facilitate transformative change. It serves as an approach to help people work with complexity and uncertainty, while also allowing for users’ agency. It has the potential to structure and guide conversations about transformations in an intuitive and accessible way. It is important to note that the Three Horizons model is a simple model to explore successful transformations. As such, it is useful with regard to our research objective, but less so for exploring how leverage for change may occur: such a leverage can work either progressively, challenging incumbent power structures and patterns, or have regressive effects and further entrench these (Stirling 2015). The framework uses an easily understandable visualization in the form of three lines, or horizons. The first line represents the incumbent system or regime (H1), the (potential) process of transition is visualized in the second line (H2), and the third line (H3) represents niches that are currently marginal but have the potential to gain momentum and become part of a new regime. These three lines are plotted against two axes, the x-axis representing time from the present into the future, and the y-axis representing the degree of the fitness of either regime or seed in, or their compatibility with, the current landscape, i.e., contextual conditions (Curry 2015; Sharpe et al. 2016). In an adapted version by Raudsepp-Hearne et al. (2019), that is slightly different from Sharpe’s original framework, the ‘horizons’ represent phases in the process of transformation, rather than systems: horizon 1 describes the current situation, with an unsustainable, incumbent system (the regime) and niches representing sustainable alternatives; horizon 2 describes the period of transition, during which both conflicts between niches and the regime, and enabling conditions for niches to pick up momentum play a crucial role; and horizon 3 represents the future situation in which the niche(s) have reached their ‘mature’ form, i.e., have flourished as part of a new regime that has replaced the old regime (Raudsepp-Hearne et al. 2019; Sharpe et al. 2016). In addition, the y-axis represents the relative dominance of the incumbent regime or seed—a slight adaption from the original Thee Horizons framework in which the y-axis showed the level of fitness in the landscape. Figure 1 shows this adapted version of the Three Horizons model by Raudsepp-Hearne et al. (2019), which we used for our research.

It is important to note that the framework describes transformations in a very simple and schematic way—in reality, the developments depicted by the framework are often less straight-forward and much more chaotic. In addition, it only describes ‘successful’ transformations, in which an incumbent regime is eventually replaced by a new regime. The Seeds approach, introduced above, was developed in response to the need to envision positive, transformational futures based on niches, or ‘seeds’ representing sustainable alternatives.

In this research, it is horizon 2 that interests us most, as this entails the process that describes the transformation from the incumbent regime to a new, more sustainable one, including the necessary power shifts. Horizon 2 can be regarded as “the turbulent domain of transitional activities and innovations” (Sharpe et al. 2016:5) and “a site of political, social and economic struggle” (Curry 2015:12). Sharpe et al. (2016) distinguish between two types of niches picking up momentum: H2+ niches, that challenge the regime in such a way that H1 will be replaced by H3, and H2− niches, that are eventually subsumed back or co-opted by H1 (Sharpe et al. 2016). These are all processes in which power relations play a key role, and although this is emphasized in the quoted literature, we argue that the question as to how such power shifts happen, i.e., the mechanisms at play in H2, remains largely unanswered. This concern is shared in the seeds community, as Raudsepp-Hearne et al. (2019) state that participants working with the Three Horizons model had difficulties in envisioning how to engage with current power structures and dynamics. They argue that linking the Seeds approach with work on radical transformations and participation of change-makers and activists may help overcome these difficulties (Raudsepp-Hearne et al. 2019).

Power shifts in transformations

In response to the abovementioned difficulties of the Seeds approach in engaging with power dynamics, we aim to expand the approach through articulating the power struggles and shifts that often remain implicit. The proposed updated approach focuses on Disruptive Seeds and allows for imagining, exploring and describing the power shifts that are needed for transformative futures. To this end, we first need to define what we mean by power—we do so by giving a brief overview of how the fields of social–ecological systems and environmental governance scholarship have treated issues of power. We then describe relevant conceptualizations of power (shifts) in transitions and transformations. Subsequently, we derive a set of guiding questions from this literature, to be used in an updated version of the Seeds approach, specifically for Horizon 2.

Historically, power dynamics have been rather under-investigated in research on governance of social–ecological systems (Clement 2010). One of the main critiques is that it often implicitly assumes that social systems function largely analogously to ecosystems (Cote and Nightingale 2012; Cleaver and Whaley 2018). A substantial literature of critiques on the lack of attention to power dynamics in social–ecological systems governance has emerged (e.g., Nadasdy 2007; Hornborg 2009; Meadowcroft 2009; Davidson 2010; Smith and Stirling 2010; Voß and Bornemann 2011; Davoudi 2012). More generally, environmental governance scholars have argued that questions relating to empowerment of marginalized groups and power dynamics between actors need greater attention (Burch et al. 2019). In this regard, we define power as the capacity of actors to realize goals (Avelino and Rotmans 2009; Avelino 2017), and to mobilize resources to achieve those goals (Parsons 1967; Pansardi 2012). We follow Pansardi, who argues that the conceptualization of power to should be viewed as linked to power over other actors—these are both aspects of social power (Pansardi 2012). Particularly relevant for our research is the notion of power dynamics brought forward by Avelino and Rotmans: a certain type of power has the ability to disrupt or break the dominance of another type of power; conversely, different types of power can enable and reinforce each other (Avelino and Rotmans 2009). A particularly interesting way of exercising power is through construction of knowledge, or through mobilization of mental resources (Avelino and Rotmans 2009).

With regard to power shifts, Avelino (2017) introduced the Power in Transition framework, aimed at analyzing power and (dis)empowerment in processes of transformative change. In this framework, she makes the well-known distinction between the regime (the incumbent system), niches (sources of innovation and change that challenge the regime) and the landscape (exogenic macro-trends, which may align with the regime or not, in which case they are called counter-macro-trends), and adds the conception of niche-regimes, or niches that gain momentum and have the potential to grow in impact to the point when they replace the current regime. Avelino describes two types of niches in her framework: moderate and radical niches. Niches potentially hold innovative power. Moderate niches may grow to become moderate niche-regimes, and similarly, radical niches may become radical niche-regimes. Moderate niche-regimes do not challenge the incumbent regime and as such, are subsumed or co-opted by the regime. Radical niche-regimes, on the other hand, exert transformative power, may align with counter-macro-trends and actively challenge the regime, which exerts reinforcing power and is aligned with dominant macro-trends (Avelino and Rotmans 2009; Avelino 2017).

A complementary framework was developed by Brisbois (2019), the Powershifts framework, in which she distinguishes three dimensions of power: instrumental, referring to the direct and visible ways of exercising power, such as “coercion, manipulation, and obvious differences in the resources that different policy actors are able to use” (Brisbois:152); structural, referring to the “structures and institutions that directly shape the exercise of political power” (Brisbois 2019:152); and discursive power, which refers to the ways in which the logic and discourse associated with social institutions, norms and values aligned with certain actors are constructed, expressed, and reproduced, for example using discursive tools such as the media. For each of these three dimensions, she formulated a set of analytical questions based on the literatures on power from different relevant fields (Brisbois 2019).

Another useful tool for analyzing transformations is the transition model canvas, developed by Van Rijnsoever and Leendertse (2020). It presents a simple template to map the key elements and interactions of a transformation: the incumbent system and its key elements and interactions, the niche system, the strengths, vulnerabilities, and uncertainties of these systems, and the strategies the incumbent system uses to defend itself, and the strategies and resources the niche system uses to destabilize the incumbent system (van Rijnsoever and Leendertse 2020). As such, this template provides a set of basic questions that are relevant for our approach—it helps make explicit the incumbent and niche systems and actors aligned with these. We combined the frameworks described in this section to inform a set of questions that can be used to deliberately guide discussions about power shifts in transformations (see Table 1).

An updated approach: Disruptive Seeds

In this section, we introduce the Disruptive Seeds approach, which builds on the original Seeds approach developed by Bennett et al. (2016). This updated approach consists of two steps: (1) envisioning a future in which a disruptive seed has become dominant and part of the regime; (2) exploring and explaining the power shifts required for the transformation from the current incumbent regime to the future envisioned during step 1. The Disruptive Seeds approach entails a participatory process, in which participants work together in small groups of three to five persons, preferably representing different sectors, stakeholder groups, and perspectives.

Step 1: Disruptive Seeds as the future regime

The first step is a slightly adapted version of the one used in the original Seeds approach—whereas the original approach aims to explore transformative futures based on two seeds and their potential synergies, the adapted approach focuses on one disruptive seed. During this step, workshop groups select a disruptive seed to work with and collectively imagine what this seed would look like in mature form. Subsequently, they decide on the time horizon to focus on (2030, 2040 or 2050), and then “Future Wheels” are used (Raudsepp-Hearne et al. 2019; see our adapted version in Fig. 4) to structure thinking about the impacts of the seed in mature form—which has flourished and become part of a new regime—on the world in which it exists. Such a Future Wheel distinguishes between 1st-order impacts and 2nd-order impacts, thereby invoking thinking about cascading effects.

Step 2: power shifts in the transformation process

Once an outline of the future world is established (step 1) by imagining the seed in its mature form and its impacts on the world in which it exists, workshop groups move to step 2 in which they use the Three Horizons model for a constructive conversation about the path towards this future. To guide this discussion, the insights on power dynamics described in “Theoretical framework” have been combined and integrated into a set of questions to elucidate power shifts, as shown in Table 1. These questions are aimed at determining what constitutes the incumbent system (the regime) and the seed challenging the incumbent system. Moreover, they help to identify actors aligned with the incumbent system and seeds, and what forms of power they exercise and which resources and strategies they use to do so. These questions complement the Three Horizons model and aim to make explicit the power struggles and shifts in exploring sustainability transformations—as such, they are particularly relevant when thinking about H2. In addition, we added an overarching question about power shifts after the first iteration: “How does this power shift happen? Describe the power struggles and shifts—how do we go from the current situation to the vision of the world in which the seed is dominant? Are there tipping points?”.

Through answering these questions, participants explore how power shifts may unfold in the transformation process. In this way, a scenario is developed which describes the transformation from the present situation to a future in which the selected seed has become dominant, emphasizing the role of power shifts.

Applying the approach: an illustration

To test the approach, we organized three online pilot workshops over the course of approximately 3 weeks, during which groups of three to four participants worked together to envision the future of a seed of their choice. We used the online platform Miro, a user-friendly online tool with a myriad of options. It is a virtual whiteboard that allows for collaboration in groups, in which content can be added using digital sticky notes—an example is shown in Fig. 2.

Participants of these pilot workshops were a representative mix of leading academics in the fields of seeds, transformations and futures, authors of key papers on power shifts, and people involved in Disruptive Seeds. In total, 22 participants divided into seven different groups developed scenario narratives describing transformations based on seven different seeds. Table 2 provides an overview of the workshops dates, the participants and the seeds they worked on—while one-paragraph summaries of the seed scenarios provided in Table 3 and more extended summaries can be found in Appendix 1. Groups were free to choose a disruptive seed to focus on, but a short list of examples was provided for inspiration. For the purpose of piloting our approach, we invited participants with knowledge and affinity about sustainability transformations for the workshops: primarily scholars familiar with the Seeds concept, transformations and futures studies in a more general sense, and practitioners who are actively involved in a disruptive seed initiative. Here, we illustrate the application of the Disruptive Seeds approach.

Overall observations

Each of the seven groups of participants focused on a unique seed. Four of them had an explicit focus on challenging fossil fuel capitalism, whereas two groups focused on indigenous practices and one on regenerative agriculture. Even though the groups worked independently from each other, a number of common threads can be identified in the transformation scenarios that were developed. A recurring element was the role of activists challenging incumbent regimes and institutions who organize in protest movements and form coalitions with other social groups. In addition, some scenarios describe how the incumbent systems become untenable, which leads them to collapse. The resulting crises can be leverage points for institutional change. Another commonality that was present throughout the scenarios is the role of democratization and decentralization of power in the transformation process. Conflicts between incumbent and seed actors were highlighted in most scenarios, in a few in the form of court cases filed by activist groups. Violent conflicts were only described in one of the transformation scenarios. Furthermore, the role of decolonization and the need for plurality of sources of knowledge and perspectives that challenge dominant Western frames were highlighted by some groups.

Step 1: Disruptive Seeds as the future regime

The first step of the process was to imagine what the seed would look like in its mature form, i.e., when the seed is part of the future regime. This was a straight-forward task—the groups found it easy to imagine. Examples include:

“Renewable energy cooperatives are mainstream (90 % of energy supply) in Southern Africa” and “Pressure by activists and societal movement to divestment from shares connected to the fossil fuel industry—has been successful everywhere”.

In addition, the groups generally had little difficulty populating the Future Wheels, elucidating the impacts of their respective seeds in mature form. In the first iteration of the Disruptive Seeds approach, participants were assigned to articulate both 1st- and 2nd-order impacts—this was adopted from the original Seeds approach. Although this is a useful exercise, it is also very time-consuming and participants primarily envisioned positive impacts of the mature seed. We, therefore, adapted this for the second iteration: participants of the subsequent workshops were assigned with the task to think about 1st-order impacts, and were then specifically asked to think about what would have changed in terms of power dynamics: who are the winners and losers of this transformation (Blythe et al. 2018)? This second question replaced the explication of 2nd-order impacts. An example of one such Future Wheel is provided in Fig. 3.

Example of a Future Wheel depicting 1st-order impacts and winners and losers of a mature seed (after Raudsepp-Hearne et al. 2019)

Step 2: power shifts in the transformation process

The second step is at the core of the approach, as it focuses on exploring how power shifts required for transformations may unfold. We found that workshop participants found the guiding questions useful for their discussions. These questions helped to systematically map the elements of the incumbent regime and associated actors, as well as the seed and actors organizing around it. Moreover, the questions helped to facilitate discussion about landscape-level developments—or macro-trends—that can be either aligned with the incumbent regime, or with the seed (see Fig. 4 for an example). Furthermore, it fostered thinking about the types of power the regime and seed use—to defend its structures or challenge them, respectively—and how deliberative means are used to exert power.

To focus the discussions on explicating how power shifts unfold, an overall question—with a number of sub-questions—was added after the first pilot workshop. This had the intended effect, as exemplified in Fig. 5.

Interestingly, the workshop groups described power shifts in a number of different ways. Such power shifts can unfold gradually, in a step-by-step fashion, for example by actors organizing in movements that gain momentum, amplified by mass media, which leads to a gradual power shift. We found that another, more abrupt way in which power shifts may unfold, is when crises trigger change—this happens for example when incumbent regimes and structures become unfit for purpose in the face of such crises, and challenging actors organized around a seed seize the opportunity for change.

Conclusions, discussion, and reflections on the Disruptive Seeds approach

This paper responds to a need for methods that support the creation of imaginative transformation pathways while attending to the roles that power dynamics and shifts play in transformations.

To do this, we extended the “Seeds of Good Anthropocenes” approach (Bennett et al. 2016), incorporating questions derived from scholarship on power into the methodology. Our ‘Disruptive Seeds’ approach focuses on niche practices that actively challenge unsustainable incumbent actors and institutions. We tested this novel approach in a series of participatory workshops. Generally, the approach shows great potential as it facilitates explicit discussion about the way power shifts may unfold in transformations. However, the approach can be improved in a number of ways.

In the first step of the approach, participants envision a future in which the disruptive seed has flourished as part of a new regime. They subsequently answer questions to form a more complete understanding of that particular future—what are the impacts of this new regime? Which actors are winners, and who are the losers of this transformation? The participants in our pilot workshops had little difficulty to envision such futures—however, the “dark side” of such transformations (Blythe et al. 2018) was often less pronounced. We assume this is due to the way we formulated the guiding questions for this step. Besides the question about winners and losers, there is no explicit question about the potential negative (side) effects of the transformation. For a future iteration of the Disruptive Seeds approach, we recommend that step 1 be extended with more explicit questions about the potential negative impacts of transformations. This can foster anticipation of (unintentional) negative consequences in planning for transformations.

The second step of the Disruptive Seeds approach is the most important adaptation—this is where participants are explicitly exploring the role of power shifts in transformations. We found that our set of questions derived from the literature (Avelino 2017; Brisbois 2019; van Rijnsoever and Leendertse 2020; Feola et al. 2021) helps to encourage dialogue about power shifts and to make them explicit. However, the set consists of quite a number of questions, with some overlap between them. We included all these questions to allow for rich dialogue and to investigate their value, but found that such a large set of questions risks distraction from the main objective of step 2. We, therefore, added an overall question explicitly about the mechanisms of power shifts after the first iteration of the approach was piloted in the first workshop. We recommend further improving the Disruptive Seeds approach by critically reflecting on the individual contribution of each of the questions—and merging questions—to increase its effectiveness.

Interestingly, the mechanisms of power shifts in transformations described in the Disruptive Seeds scenarios are to some extent compatible with a number of more established theories from the literature on policy change. In several of the seeds scenarios developed during the pilot workshops, the role of actors organizing in coalitions gaining momentum was prominent—this is in line with Paul Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework (Sabatier 1988; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 2007). In this framework, the concept of advocacy coalitions refers to alliances of different actors that align “around a shared policy goal” (Weible and Ingold 2018:325). These advocacy coalitions are often informal networks that oppose other such coalitions with conflicting objectives (Sabatier 1988; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 2007). Other relevant policy change theories include the Multiple Streams Framework (Kingdon 1995) and Punctuated Equilibrium Theory (Baumgartner and Jones 1993). Both theories emphasize the importance of momentum for policy change: in Kingdon’s framework, this manifests itself in the form of a “policy window”—an opportunity that can be seized by “policy entrepreneurs” to push their policy agendas—whereas Baumgartner and Jones stress the role of bounded rationality—because of the inherently limited human cognitive ability, policy makers can only focus on a limited scope of policy issues, they argue. Changes of—for example—administration, or of public discourse, can shift policy makers’ attention to certain policy issues, thereby creating momentum for sudden change (Jones and Baumgartner 2012; Cairney 2015). While these theories were developed to describe and explain more gradual policy change, we argue that they can help to understand and anticipate processes of transformational change as well—such “policy windows” or “punctuated equilibria” can be leverage points for power shifts in transformations, and actors aligned with either incumbent regimes or Disruptive Seeds can be considered as competing advocacy coalitions. In a next iteration of the Disruptive Seeds approach, key concepts from these theories—e.g., policy windows, punctuated equilibria, advocacy coalitions, and policy entrepreneurs—can be incorporated in the set of questions to more explicitly explore such leverage points, as well as add further rigor to the scenario narratives and descriptions of transformations—this should be done carefully, to avoid steering the process too much and unintentionally limiting the space for imagination.

Finally, we contend that the Disruptive Seeds approach is in essence a visioning and back-casting approach—participants envision a desirable future and subsequently explore how this future can be realized. In addition, while such an approach is useful for envisioning hopeful futures in the face of global challenges and for instigating transformational policies that provide an enabling environment for seeds, it does not account for uncertainty. We, therefore, recommend that the Disruptive Seeds approach be used in combination with an explorative scenario approach. In its current prototype form, the Disruptive Seeds approach allows for exploration of power shifts in transformations, without regard of the role of uncertain, contextual conditions. Sets of explorative scenarios can be used to investigate how different contextual conditions impact the way such power shifts manifest, informed by insights from theories on policy change mentioned above: what is the role of advocacy coalitions in power shifts? How do external shocks and policy windows impact the way power shifts unfold? In turn, this can inform transformational policy formulation that is better acquainted with critical uncertainties.

The Disruptive Seeds approach is a strong example of the value of mixing disciplinary perspectives to create new forms of scenario thinking—following the call for more integrated work on anticipatory governance (Vervoort and Gupta 2018) that combines futures thinking with social and political science research into governance and power. Specifically, the questions about power shifts in transformations used in this paper to adapt the Seeds approach can also be used to adapt other futures methods that similarly lack a focus on power shifts—for instance, explorative scenarios (Wiebe et al. 2018; Rutting et al. 2021), classic back-casting approaches (Kok et al. 2011), and simulation gaming (Vervoort et al. 2022). Applying the Disruptive Seeds approach in a transdisciplinary way, with actors actively involved in Disruptive Seeds of transformational change, can help to leverage bottom-up alternatives by actively challenging unsustainable incumbent systems.

References

ABC News (2021) Climate change activists win against Exxon Mobil and Chevron, Shell loses Dutch court case. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-27/climate-environment-shell-chevron-exxon/100169518

Avelino F (2011) Power in transition: Empowering Discourses on Sustainability Transitions (PhD thesis). Erasmus University Rotterdam

Avelino F (2017) Power in sustainability transitions: analysing power and (dis)empowerment in transformative change towards sustainability. Environ Policy Gov 520:505–520

Avelino F, Rotmans J (2009) Power in transition: an interdisciplinary framework to study power in relation to structural change. Eur J Soc Theory 12:543–569

Avelino F, Wittmayer JM (2016) Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: a multi-actor perspective shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: a multi-actor perspective 7200

Baumgartner F, Jones B (1993) The politics of disequilibrium: agendas and advantage in American. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Bennett EM, Solan M, Biggs R, McPhearson T, Norström AV, Olsson P, Pereira L, Peterson GD, Raudsepp-Hearne C, Biermann F, Carpenter SR, Ellis EC, Hichert T, Galaz V, Lahsen M, Milkoreit M, Martín-López B, Nicholas KA, Preiser R, Vince G, Vervoort JM, Xu J (2016) Bright spots: seeds of a good Anthropocene. Front Ecol Environ 14:441–448

Blythe J, Silver J, Evans L, Armitage D, Bennett NJ, Moore M, Morrison TH, Brown K (2018) The dark side of transformation: latent risks in contemporary sustainability discourse. Antipode 50:1206–1223

Brisbois MC (2019) Powershifts: a framework for assessing the growing impact of decentralized ownership of energy transitions on political decision-making. Energy Res Soc Sci 50:151–161

Burch S, Gupta A, Inoue CYA, Kalfagianni A, Persson Å, Gerlak AK, Ishii A, Patterson J, Pickering J, Scobie M, Van Der Heijden J, Vervoort J, Adler C, Bloom M, Djalante R, Dryzek J, Galaz V, Jinnah S, Kim RE, Gordon C, Olsson L, Van Leeuwen J, Ramasar V, Wapner P, Zondervan R (2019) New directions in earth system governance research. Earth System Governance 1:100006

Cairney P (2015) How can policy theory have an impact on policymaking? The role of theory-led academic-practitioner discussions. Teaching Public Administration 33:22–39

Chapin FS III, Carpenter SR, Kofinas GP, Folke C, Abel N, Clark WC, Olsson P, Smith DMS, Walker B, Young OR, Berkes F, Biggs R, Grove JM, Naylor RL, Pinkerton E, Steffen W, Swanson FJ (2009) Ecosystem stewardship : sustainability strategies for a rapidly changing planet. Trends Ecol Evol 25:241–249

Cleaver F, Whaley L (2018) Understanding process, power, and meaning in adaptive governance: a critical institutional reading. Ecol Soc 23

Clement F (2010) Analysing decentralised natural resource governance: proposition for a “politicised” institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Sci 43:129–156

Cote M, Nightingale AJ (2012) Resilience thinking meets social theory : Situating social change in socio-ecological systems ( SES ) research. Prog Hum Geogr 36:475–489

Curry A (2015) Searching for systems: understanding three horizons. Association of Professional Futurists Compass 11–13

Davidson DJ (2010) the applicability of the concept of resilience to social systems: some sources of optimism and nagging doubts. Soc Nat Resour 23:1135–1149

Davoudi S (2012) Resilience: a bridging concept or a dead end? Plan Theory Pract 13:299–333

Feola G (2015) Societal transformation in response to global environmental change: a review of emerging concepts. Ambio 44:376–390

Feola G (2019) Degrowth and the unmaking of capitalism: beyond “decolonization of the imaginary.” Acme 18:977–997

Feola G, Koretskaya O, Moore D (2021) (Un)making in sustainability transformation beyond capitalism. Glob Environ Chang 69:102290

Geels FW (2002) Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res Policy 31:1257–1274

Geels FW, Schot J (2007) Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res Policy 36:399–417

Ende Gelände (n.d.) Ende Gelände—Stop Coal. https://www.ende-gelaende.org/en/. Accessed 10 Oct 2021

Hölscher K, Wittmayer JM, Loorbach D (2018) Transition versus transformation: What’s the difference? Environ Innov Soc Trans 27:1–3

Hornborg A (2009) Zero-sum world: challenges in conceptualizing environmental load displacement and ecologically unequal exchange in the world-system. Int J Comp Sociol 50:237–262

IPCC (2021) Climate change 2021: the physical science basis—summary for policymakers

Jackson T (2009) Prosperity without growth economics for a finite planet. Earthscan, London

Jasanoff S, Kim S, Jasanoff S, Kim S (2013) Sociotechnical imaginaries and national energy policies. Science as Culture 22:189–196

Jones BD, Baumgartner FR (2012) From there to here: punctuated equilibrium to the general punctuation thesis to a theory of government information processing—Jones—2012—Policy Studies Journal—Wiley Online Library. Policy Stud J 40:1–20

Kingdon J (1995) Agendas, alternatives and public policies. Page Agendas, alternatives and public policies, 2nd edn. Longman, New York

Kok K, Van Vliet M, Bärlund I, Dubel A, Sendzimir J (2011) Combining participative backcasting and exploratory scenario development: experiences from the SCENES project. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 78:835–851

Leach M, Scoones I, Stirling A (2010) Dynamic sustainabilities: technology, environment, social justice. Routledge, Milton Park

Meadowcroft J (2009) What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long term energy transitions. Policy Sci 42:323–340

Muiderman K, Gupta A, Vervoort J, Biermann F (2020) Four approaches to anticipatory climate governance: different conceptions of the future and implications for the present. Wires Clim Change 673:1–20

Nadasdy P (2007) Adaptive co-management and the gospel of resilience. In: Armitage D, Berkes F, Doubleday N (eds) adaptive co-management: collaboration, learning, and multi-level governance. UBC Press, Vancouver, pp 208–227

Olsson P, Galaz V, Boonstra WJ (2014) Sustainability transformations: a resilience perspective. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06799-190401

Pansardi P (2012) Power to and power over : two distinct concepts of power? Journal of Political Power 5:73–89

Parsons T (1967) On the concept of political power: Sociological theory and modern society. London, UK, Free Press

Patterson J, Schulz K, Vervoort J, Van Der Hel S, Widerberg O, Adler C, Hurlbert M, Anderton K, Sethi M, Barau A (2017) Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environ Innov Soc Trans 24:1–16

Pereira LM, Bennett E, Biggs RO, Peterson G, Mcphearson T, Norström A, Olsson P, Preiser R, Raudsepp-Hearne C, Vervoort J (2018a) Seeds of the Future in the Present: Exploring Pathways for Navigating Towards “Good” Anthopocenes. In: Elmqvist T, Bai X, Frantzeskaki N, Griffith C, Maddox D, McPhearson T, Parnell S, Romero Lankao P, Simon D, Watkins M (eds) Urban planet: knowledge towards sustainable cities. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 327–350

Pereira LM, Hichert T, Hamann M, Preiser R, Biggs R (2018b) Using futures methods to create transformative spaces: visions of a good Anthropocene in southern Africa. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09907-230119

Pereira L, Asrar GR, Bhargava R, Hesse L, Angel F, Jason H (2021) Grounding global environmental assessments through bottom—up futures based on local practices and perspectives. Sustain Sci 16:1907–1922

Raudsepp-Hearne C, Peterson G, Bennett E, Biggs R, Norström A, Pereira L, Vervoort J, Iwaniec D, McPhearson T, Olsson P, Hichert T, Falardeau M, Jiménez Aceituno A (2019) Seeds of good anthropocenes: developing sustainability scenarios for Northern Europe. Sustain Sci 15:605–617

Ribot J (2011) Vulnerability before adaptation: toward transformative climate action. Glob Environ Chang 21:1160–1162

Rutting L, Vervoort JM, Mees H, Driessen PPJ (2021) Participatory scenario planning and framing of social-ecological systems: an analysis of policy formulation processes in Rwanda and Tanzania. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12665-260420

Rutting L, Vervoort JM, Mees HLP, Driessen PPJ (2022) Strengthening foresight for governance of social-ecological systems: an interdisciplinary perspective. Futures 141:102988

Sabatier PA (1988) An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sci 21:129–168

Sabatier PA, Jenkins-Smith HC (2007) The advocacy coalition framework. In: Theories of the policy process, pp 189–220

Sharpe B, Hodgson A, Leicester G, Lyon A, Fazey I (2016) Three horizons: a pathways practice for transformation. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08388-210247

Smith A, Stirling A (2010) The politics of social-ecological resilience and sustainable socio-technical transitions. Ecol Soc 15:11

Stirling A (2015) Emancipating transformations—from controlling ‘the transition’ to culturing plural radical progress. In: Scoones I, Leach M, Newell P (eds) The politics of green transformations. Routledge, London, pp 54–67

The Guardian (2018) Dutch appeals court upholds landmark climate change ruling. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/oct/09/dutch-appeals-court-upholds-landmark-climate-change-ruling

The Guardian (2021) One of world’s biggest pension funds to stop investing in fossil fuels. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/oct/26/abp-pension-fund-to-stop-investing-in-fossil-fuels-amid-climate-fears

van Rijnsoever FJ, Leendertse J (2020) A practical tool for analyzing socio-technical transitions. Environ Innov Soc Trans 37:225–237

Vervoort J, Gupta A (2018) Anticipating climate futures in a 1.5°C era: the link between foresight and governance. Current Opinion in Environmental. Sustainability 31:104–111

Vervoort J, Mangnus A, Mcgreevy S, Ota K, Thompson K, Rupprecht C, Tamura N, Moossdorff C, Spiegelberg M, Kobayashi M (2022) Unlocking the potential of gaming for anticipatory governance. Earth System Governance 11:100130

Voß J-P, Bornemann B (2011) The politics of reflexive governance: challenges for designing adaptive management and transition management. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04051-160209

Walker B, Holling CS, Carpenter SR, Kinzig A (2004) Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social—ecological Systems. Ecol Soc 9:5

Weible CM, Ingold K (2018) Why advocacy coalitions matter and practical insights about them. Policy Polit 46:325–343

Westley F, Olsson P, Folke C, Homer-dixon T, Vredenburg H, Loorbach D, Thompson J, Lambin E, Sendzimir J, Banerjee B, Galaz V, Van Der Leeuw S (2011) Tipping toward sustainability: emerging pathways of transformation. Ambio 40:762–780

Wiebe K, Zurek M, Lord S, Brzezina N, Gabrielyan G, Libertini J, Loch A, Thapa-Parajuli R, Vervoort J, Westhoek H (2018) Scenario development and foresight analysis: exploring options to inform choices. Annual Reviews of Environment and Resources 43:545–570

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Handled by Kirsten Maclean, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Australia.

Appendix 1: the Disruptive Seeds scenarios

Appendix 1: the Disruptive Seeds scenarios

Renewable energy cooperatives in Southern Africa

The energy system in Southern Africa is no longer fit for purpose: it depends on a centralized grid and fossil fuels, and is ruled by a small elite who keeps knowledge and influence in their own circles (so-called “red tape deluxe”). This elite consists of the ruling political party, the fossil fuel lobby and large energy corporations and miners, especially in coal. Energy cooperatives have the power to de-centralize this system and introduce renewable energy sources as the default. This requires physical and governance system transformations. The power shift to the energy co-operations and a decentralized energy system is driven by a number of events. First, a protest movement grows, spurred on by recent global debates on climate change and justice. The people driving this movement are opposition politicians, activists, progressive civilians, and in general people who are affected by the constant power-outs in the region which are a persistent nuisance. The South African media, which is independent and critical, reports and amplifies the protests and the ongoing energy cooperative developments. Activist shareholders, which are common in Southern Africa, force regime energy corporations to shift investments to renewables and a decentralized grid. After some years of investment and spreading of the cooperatives, the energy starts to become cheaper, making the cooperatives more attractive to a wider range of people, especially lower income households. The mainstreaming of the cooperatives model means a shift in the governance, ownership and profit paradigms. This new system requires new partnerships, e.g., between civilians to start cooperatives, and between the cooperative leaders and energy grid technicians, or solar power developers. Ultimately, all these drivers are what makes the old regime topple over and break the elite caption of Southern Africa’s energy system.

Divestment from fossil shares in Europe and India

This future is characterized by changes due to activists and social movement pressure. This caused a full divestment from shares connected to the fossil fuel industry. The success of this has the consequence of a democratization of the economic system and the parallel empowerment of citizens to engage with moral dimensions of financial investment. The democratization also swooped into other sectors and citizens are demanding greater levels of checks and balances of power in central structures, be it in the economic but also the political system. With the focus on moral dimensions, also other aspects such as disparities and inequalities have become big concerns for investors. This higher reflexivity of civil society results in more support (e.g., through special programs and subsidies) for marginalized groups. The divestment from fossil fuel-related industries brings changes in the energy system, transportation, but also production of everyday products (e.g., plastics). New alternatives exist but might be at a higher cost which is a challenge for poorer groups in society. Thus, the support and programs are in place to balance costs in an equitable manner. The shifts in the different systems have consequences for people formerly hired in them (e.g., miners) as well as for climate pathways. In countries of the Global South, jobs like in mining and other unskilled labor have become abundant. The agrarian and energy system are now oriented towards smaller and more local production systems. As a consequence, there are more decentralized decision-making structures, individuals have more power, and bureaucratic corruption has declined. This fosters democratization efforts and a greater sentiment of public sentiment. These processes foster decolonization in the Global South and the development of own, non-colonized pathways adapted to the local context.

Artificial intelligence based on indigenous knowledge

This scenario draws on the assumption that if Artificial intelligence (AI) is to support sustainable and just futures, it should embrace more plural form of knowing. We foresee a dual strategy of unseating Western Science—and its forms of monitoring, measuring, evaluating and interpreting, as well as embracing and experimenting with non-Western forms of knowing. Traditional or Indigenous protocols for AI not only center Indigenous concerns, they simultaneously allow for more socially and environmentally oriented values to come to the fore in algorithms, for example: prioritization of collective values, non-human actors, future generations, wellbeing, etc. In doing so, an indigenous approach to AI critiques the fundamental flaws of present-day AI that too often serve the interests of powerful elites who rarely question the politics of their algorithms. At the same time, this seemingly apolitical nature of AI is increasingly questioned, as discriminating structures of patriarchy, racism, and sexism are increasingly spotlighted. For our seed to mature, and essentially as a basis for conflict, we consider it of key importance to make transparent what algorithms are doing and how they shape outcomes. Questions such as what biases and privileges feed into the algorithms require more active deliberation. Artistic methods and visualizations may play an important role in making the invisible visible.

We imagine that incumbent actors are likely to defend present-day AI with a strong individualist and/or freedom rhetoric, along the lines of: “we are not forcing you to do anything, we are merely helping you to understand what you want”. With AI rendered neutral of purely technical by most product owners, continued efforts to make visible AI’s agency and political power are unavoidable—an effort in which we foresee various suppressed groups coming together in solidarity. Next to product owners, users of commercial algorithms are an important source of legitimation. Given that all of us are continuously exposed to a variety of algorithms that tailor our everyday life—while listening to music, scrolling through our twitter feeds or planning a bike-trip, we (as users) may not be willing to question AI’s politics as they are simply too comfortable to let go off.

In a future in which all AI builds on Indigenous protocols, ownership of AI is brought back to local communities, who for example decide what questions count; and the best use of AI for their local contexts. In a world beyond commercial control of AI, AI is no longer used to serve systems of oppression but can be considered as a tool for community sovereignty and democracy. A wonderful example of this, which indeed inspired our seed, is the Indigenous AI initiative, which explores in philosophical and tangible ways—what it could look like to reimagine AI in such way (see: https://www.indigenous-ai.net/position-paper). It is, therefore, crucial to continue to make concrete the alternative possibilities for how algorithms can be designed and can function, and to engage diverse actors both involved in and affected by existing algorithms. This future may indeed even mean ‘de-algorithmatization’—or the use of fewer algorithms to drive or choices, as well as the pluralization of algorithms, by making algorithms that inherently evolve to include and diversify rather than exclude and simplify.

Energy communities in the UK

In this scenario, the existing energy system collapses, either intentional or due to internal failure. As a consequence, the regulatory rules that were originally intended to preserve the existing regime are changed—this will be contested by incumbents. This is followed by continued expansion of alternative options for energy systems—and expansion of awareness of these alternatives. Actors who want to see these changes happen (e.g., cities, community groups, and activist networks) align and organize. In general, people getting fed up with always being busy, exponential growth imperatives, always doing more, committing their lives to the current system—and start to investigate other ways of doing things/engaging in the world. This leads to a situation in which energy communities regulate the UK’s energy system. As such, communities have access to a reliable and affordable source of energy. Profit-making will not be the main objective for these communities as they are supposed to be servicing and be supportive of societal activities. New patterns of ownership emerge with implications for democracy/agency/decision-making and also with implications for distribution of economic benefits of energy production. It leads to new geographies of production and distribution of energy, potential new geographies of living (e.g., shift away from high-density urban areas?).

Complete ban on carbon-intensive ads

In this scenario, momentum for change is important. Landscape-level disruptive macro-trends, such climate change-related crises and pandemics, play a key role. Different groups of actors find strength and solidarity in fighting the incumbent systems that they hold accountable for these crises: they point out how the system reproduces itself at all levels, specifically pointing to carbon-intensive ads. Through challenging our academic leadership (be humble) and questioning privilege and institutional legitimacy, their agenda gains momentum. They use algorithms as a way for “less attractive” ideas to gain more momentum; they manage to use them to spread ideas. This transformation does not happen smoothly, as it is met with (sometimes violent) resistance of powerful incumbents in the fossil fuel sector. But eventually it leads to a complete ban on carbon-intensive ads (fossil fuel industry/airlines/polluting cars/meat/dairy/clothing).

Community governance (Zapatistas, Rojava, etc.)

In this scenario, local (indigenous) people get organized, do research to find land they can occupy and own. Communities become less dependent on outside goods and services. They become self-sufficient and set up an alternative trading system with other communities. Tipping point is when people can access food and basic needs regardless of their social status and productivity. Elites will activate police/military/mercenary forces to return to former state of affairs. They kick people out of land and kidnap occupiers of non-used land. Increasing public support will encourage state to lever land to occupying communities. Big companies lose power and eventually become bankrupt, since the system does not need such concentrated power/production anymore. Decision-making is made bottom-up with help of the whole community, and more horizontal approach that also takes special attention to groups marginalized by the colonial capitalist system (Indigenous Peoples, people of color, people who do not identify as cis men, etc.). As a result, the amount of self-sustaining communities increases, and it becomes one of the main ways to exist.

Regenerative farming

The current regime is characterized by monopolization: a few companies worldwide dominate the agricultural food system (from pesticides, fertilizers, to agricultural tools, etc.). We are in a globalized food system where prices are set internationally, and the market plays a big role. The main focus is on production with monocultures with the use of chemicals, with all kinds of negative effects on the environment as a result. Moreover, the price of food does not contain the effects it has on the environment (there are externalities). There is a top-down approach to knowledge production, to ways of financing.

We envision a power shift that would occur through awareness raising of the negative impacts of the current system (environmental, social, health, and economic effects) and of the positive impacts of alternative/regenerative farming practices (equitable labor practices, positive (physical and mental) health of consumers, and ecological restoration). Massive campaigning/mass mobilization in new alliances, legal challenges (taking companies to court), lobbying by NGOs, engaging with agenda setting by people/organizations/NGO’s that are for a more sustainable form of farming, seed thinking, and change of basic socio-economic structures (for instance basic income) will need to happen in order for people that participate more in food production (localization vs globalization), change of knowledge and property rights system, change of landownership right, and changing monopolization of the system. Potential tipping points could be: changing the current funding model within CAP, subsidy systems, and creation of outreach organization that involve people with regenerative farming.

Eventually, this process of transformation would lead to a world in which regenerative farming is the norm, and in which polyculture and traditional practices have largely replaced the current intensive monoculture-dominated system. More people are involved in food production, and distribution of food over long distances has disappeared. There is less food waste, and dietary preferences have changed to less meat-intensive diets, in part due to meat tax. The global economy in this scenario can be called an “ecology-economy”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rutting, L., Vervoort, J., Mees, H. et al. Disruptive seeds: a scenario approach to explore power shifts in sustainability transformations. Sustain Sci 18, 1117–1133 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01251-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01251-7