Abstract

Background

Housing security is a key social determinant of behavior related to health outcomes.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to develop a new patient-reported outcome measure that evaluates aspects of housing security for use in the Re-Engineered Discharge for Diabetes-Computer Adaptive Test (REDD-CAT) measurement system.

Design

Qualitative data, literature reviews, and cross-sectional survey study.

Participants

A total of 225 people with T2DM provided responses to the items in this item pool.

Main Measures

A new item pool that evaluates important aspects of housing security was developed using stakeholder data from focus groups of persons with T2DM.

Key Results

For the Housing Affordability scale, factor analysis (both exploratory and confirmatory) supported the retention of six items. Of these items, none exhibited sparse cells or problems with monotonicity; no items were deleted due to low item-adjusted total score correlations. For the six affordability items, a constrained graded response model indicated no items exhibited misfit; thus, all were retained. No items indicated differential item functioning (examined for age, sex, education, race, and socioeconomic status). Thus, the final Affordability item bank comprised six items. A Housing Safety index (three items) and a Home Features index (eight items) were also developed. Reliability (i.e., internal consistency and test–retest reliability) and validity (i.e., convergent, discriminant, and known-groups) of the new measures were also supported.

Conclusions

The REDD-CAT Housing Security Measure provides a reliable and valid assessment of housing affordability, safety, and home features in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Future work is needed to establish the clinical utility of this measure in other clinical populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Portions of this manuscript have been previously presented at the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine:

Carlozzi, N.E., Kallen, M.A., Moldovan, I., Bragg, A., Howard, J.M., Miner, J.A., Graves, C., & Mitchell, S.M. (2021, September). The Re-Engineered Discharge for Diabetes Computer Adaptive Test (REDD-CAT): New patient-reported outcome measures that evaluate social determinants of health for persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Invited oral poster presentation accepted for presentation at the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (ACRM); virtual meeting (due to COVID-19 pandemic).

The relationship between housing and health has been well-established in public health research with housing conditions, stability, affordability, and location as key areas for intervention.1 The Shaw conceptual model of housing and health further illustrates that hard factors (physical or material) and soft factors (social or meaningful) can both directly and indirectly impact health.2 Specifically, housing conditions, housing structure, and homelessness (hard factors), and individual perceptions, impact of poor housing on mental health, worries about affordable housing, and feelings of security (soft factors) directly impact health.2 Additionally, income, wealth, and proximity to services and facilities (hard factors), as well as household culture (soft factors), can indirectly impact health. At the neighborhood level, availability of local services/facilities and features of the environment (hard factors), as well as community culture and cohesion (soft factors), also indirectly impact health.2

While previous research has established that lack of or insufficient housing can have a deleterious impact on health, our ability to quantify this impact is limited by the lack of a consensus definition for housing insecurity. Definitions of housing insecurity can include any or all of the following components: housing stability, housing affordability, housing quality, housing safety, and/or homelessness.3 As such, the measures that have been used to assess housing security are equally varied. In fact, a recent systematic review identified 14 different screening tools that varied in terms of concepts measured, number of items, and psychometric rigor (for a detailed review of these measures, see 3). No measures were identified that exhibited comprehensive reliability and validity data, and most studies only employed a single item to assess housing, which, by design, only focuses on a single aspect of housing and has limited response option variability.

Despite lacking a consensus definition and a consensus measure, housing insecurity remains a key social determinant of health.1,2 Census-based estimates indicate that more than 25% of households are cost burdened (i.e., at least 30% of their household income goes toward rent),4 with even higher rates of individuals indicating concerns about housing affordability (rates range between 59.9 and 72.8% by state).5 Housing insecurity is also associated with increased risk for physical and mental health problems6,7,8,9,10,11 and with poor access to ambulatory care and high rates of acute care.12 People with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are among those populations with high rates of housing unaffordability and housing insecurity.12,13,14,15,16 In T2DM, these high rates of housing insecurity are disruptive to the self-management routines that are critical to the successful treatment and maintenance of the disease,17,18 and they increase the risk for poor health outcomes (including elevated blood glucose levels, high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, overall worse health-related quality of life).14,19,20,21,22,23 Not surprisingly, housing insecurity in T2DM is also costly, with associated elevations in diabetes-related emergency department use, hospitalization, and outpatient visits15,23,24,25,26.

We aimed to develop and validate a new comprehensive patient-reported outcome measure (PRO) of housing insecurity that could be used to better understand the impact that housing has on health outcomes at the point of discharge from the hospital. We operationalized housing insecurity as a multidimensional concept that includes housing instability, housing affordability, housing safety, housing quality, neighborhood quality, and homelessness, all of which disproportionally impact low-income families in the USA.12 Specifically, this new measure was developed as part of a larger study focused on developing and validating measures that capture important social determinants of behavior.27,28,29 We tested this measure in people with T2DM, although we would expect this measure to have broad applicability across a number of diverse clinical populations This report describes the development of this new PRO, the Re-Engineered Discharge for Diabetes Computer Adaptive Test (REDD-CAT) Housing Security measure, and provides preliminary score reliability and validity data.

METHODS

Study Participants

A total of 225 individuals with T2DM participated in this study. Study eligibility included a clinical diagnosis of T2DM, > 18 years of age, ability to communicate in English, and ability to provide informed consent. In order to complete the PROs independently, participants had to have at least a 5th grade reading level, which was confirmed by correctly pronouncing the first 10 words on the Wide Range Achievement Test 4th Edition (WRAT4) Reading Subtest;30 participants with errors on the first 10 words were provided assistance with reading survey items. Study participants were recruited from the Boston Medical Center (BMC) healthcare system using three different screening approaches: (1) weekly lists were generated of diabetes patients with upcoming outpatient appointments using BMC’s Clinical Data Warehouse; (2) the electronic health record was queried to generate inpatient census reports of inpatients with T2DM; and (3) participants that had agreed to be contacted for future research studies (as part of the consent process for a previous T2DM research study) were contacted. Data were collected in accordance with the local institutional review board, and study participants provided informed consent prior to their participation in this study.

Measures

The REDD-CAT Housing Security PRO

This new PRO was developed using published measurement development standards31 that include both qualitative and quantitative methodology (e.g., classical test theory and item response theory).32,33,34 Literature reviews and semi-structured interviews informed the development of the Housing Security items. Specifically, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 37 patients admitted to a general medical hospital service to identify patient-reported aspects of readmission risk (https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2012/pilot-project-figuring-out-which-patients-are-likely-return-hospital and Cancino et al., 201435). This work identified 15 themes related to readmission risk including housing insecurity (housing instability, housing affordability, housing safety, housing quality, neighborhood quality, and homelessness) that served as the basis for Housing Security items. Item writing relied considerably on the content from the semi-structured interviews; verbatim quotations from the patient interviews were used to develop this content when available. Item writing was iterative and included cognitive interviews with patients with a recent hospital readmission, expert review (i.e., professional inpatient providers; PRO development experts), reading level review (reading level does not exceed the 6th grade), and translatability review (to inform future adaptation into languages other than English). See Fig. 1. The final Housing Security PRO has 22 items and includes three broad subdomains (housing safety [3-item index], housing affordability [6-item scale], and housing features [8-item index]). There are also five stand-alone single items (post-discharge housing status; anxiety about affording housing; safety: domestic violence; anxiety about where will sleep next; and reason(s) staying with family/friends/at a shelter). Scores include a Housing Affordability T-score (M = 50, SD = 10; higher scores indicate less worry about affordability) and Housing Safety and Housing Features index scores (summed scores divided by the number of completed items in the index; higher scores indicate more safety and more available housing features, respectively). The “anxiety about affording housing,” “domestic violence,” and “anxiety about where will sleep next” single items provide scores ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating less anxiety about affording housing, more personal safety, and less anxiety about where will sleep next.

Validity Measures

The 8-item Economic Quality of Life (Econ-QOL)36 was used to evaluate perceived economic and financial security. This measure is scored on a T-score metric (M = 50; SD = 10); higher scores indicate worse perceived economic quality of life. We examined those with “better” (scores ≤ 40) versus “worse” (scores ≥ 60) economic quality of life.

PROMIS Severity of Substance Use37,38 provided a measure of self-reported severity of substance use in the last 30 days, Neuro-QoL Anxiety39,40 provided a measure of perceived worry, fear, and hyperarousal, and PROMIS Pain Interference provided a measure of the effects of pain on a range of daily life activities. These measures are scored on a T-score metric (M = 50; SD = 10); higher scores indicate worse severity, anxiety, and pain interference, respectively.

We also collected demographic data and several medical record variables including questions about health insurance and finances.

Data Capture

The study PROs were administered using a HIPPA-compliant electronic data capture system; study participants used either a personal internet-enabled device or a study-specific tablet or laptop to provide item responses.

Sample Size Justification

Sample size requirements were based on the planned graded response model (GRM) analysis and differential item functioning (DIF) analyses that were conducted as a part of the PRO development (specific analyses described below). The proposed GRM analysis required a minimum sample size of N = 200 to generate stable calibration estimates for the PRO.41,42 In addition, Wald-2-based DIF analyses required at least n = 100 participants per subgroup for the proposed demographic comparisons.43

Statistical Analyses

Housing Affordability Scale Development

The Housing Affordability scale was developed using an iterative process that included classical test theory and item response theory approaches, as well as clinical input.32,33,34 Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (EFA, CFA; using Mplus software version 7.444) were used to examine scale dimensionality. EFA was used to help identify the number of potential scale subdomains. Items with sparse cells (response categories with n < 5 respondents), low item-adjusted total score correlations (r < 0.40), or items that were non-monotonic (Testgraf Software45) were candidates for exclusion. In CFA analyses, items were candidates for exclusion if they exhibited: low factor loadings (lx < 0.50), or local dependence (residual correlations > 0.20 or a correlated error modification index ≥ 100).32,33,34 CFA was used to confirm the factor structure of potential item sets. Fit criteria were as follows: comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ 0.90; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ≥ 0.90; and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.15.46,47,48,49

Next, a constrained, common-slope graded response model (GRM)50 was used to identify items with significant misfit (S-X2 /df effect size > 3)51. This was followed by an investigation for potential differential item functioning (DIF). Items exhibiting meaningful DIF (p < 0.01 group-specific item parameter difference, plus > 2% of DIF-corrected vs. uncorrected score differences exceeding individual case uncorrected score standard errors) were candidates for exclusion. DIF was examined for age (< 60 vs. ≥ 60 years), sex (male vs. female), education (≤ high school vs. > high school), and socioeconomic status (“have enough income to pay rent/mortgage” and “can afford to pay bills on time,” both categorized as never/rarely/sometimes vs. usually/always). Analyses were conducted using IRTPRO software version 3.1.2.52 CFA was also used to confirm the factor structure of the final item set.

Housing Safety and Housing Features Index Development

The Housing Safety and Housing Features indices were developed using an iterative process focused primarily on classical test theory. As with the Housing Affordability scale, EFA and CFA were used to examine dimensionality, following the analytic process outlined above. The multi-dimensional nature of item content precluded a typical unidimensional scale development strategy; the indices, instead, were designed to provide a “count” and an “extent to which” different safety elements and housing features are present.

Preliminary Reliability and Validity Analyses: Housing Affordability

Given that the item response data were normally distributed, we proceeded with parametric analyses. Scores on the new Housing Affordability PRO were examined. Cronbach’s alpha was used to estimate internal consistency reliability (a priori criterion specified as ≥ 0.70).53 Floor and ceiling effects were also examined (a priori criterion specified as ≤ 20%).54,55

Convergent and discriminant validities were examined using Pearson correlations. Convergent validity would be supported by moderate correlations (r’s ≥ 0.36–0.67) between Housing Affordability and Economic Quality of Life.56 Discriminant validity would be supported by less robust or “low” correlations (r’s ≤ 0.35) between Housing Affordability and Neuro-QoL Anxiety, and negligible correlations between Housing Affordability and PROMIS Pain Interference.56

Independent sample t-tests were used to examine known-groups validity. Known-groups categories included those indicating they have enough money to make ends meet versus those who do not have enough money to make ends meet. We expected those who report that they do not have enough money to make ends meet would report more housing insecurity than those with enough money to make ends meet.

In addition, logistic regression models were conducted to determine if Housing Security was related to readmission risk in our sample (high risk was defined as ≥ 2 inpatient admissions in the past 6 months; low risk was defined as ≤ 1 inpatient admission in the past 6 months). These models included patient demographic variables, objective medical record data, existing hospital risk assessment data, and PRO measure scores.

Preliminary Descriptive and Validity Analyses: Housing Safety and Housing Features

Given that Housing Safety and Housing Features scores are count- and extent-based in nature and thus non-normally distributed, we proceeded with nonparametric analyses. Scores on these two new Housing Security indices were examined, with minimum, maximum, median, and modal observed scores reported. The percent of cases with minimum and maximum possible scores was also reported.

Convergent and discriminant validities were examined using Spearman correlations. Convergent validity would be supported by moderate correlations (r’s ≥ 0.36–0.67) between Housing Safety and Housing Features vs. Severity of Substance Use.56 Discriminant validity would be supported by low correlations (r’s ≤ 0.35) between Housing Safety and Housing Features vs. Neuro-QoL Anxiety, as well as negligible correlations between Housing Safety and Housing Features vs. PROMIS Pain Interference.

Mann–Whitney U tests were used to examine known-groups validity. Known-groups categories included (1) those with enough money to make ends meet versus those without enough money to make ends meet; and (2) “worse” vs. “better” economic quality of life. We expected those without enough money to make ends meet to report less housing safety and less housing features than those with enough money to make ends meet; we also expected those with “worse” economic quality of life to report less housing safety and less housing features versus those with “better” economic quality of life.57

Preliminary Descriptive Analyses: Anxiety About Affording Housing, Domestic Violence, and Anxiety About Where Will Sleep Next

Given that there were only single items each to assess “anxiety about affording housing,” “domestic violence,” and “anxiety about where will sleep next,” we reported each item’s minimum, maximum, median, and modal observed scores, as well as the percent of cases with minimum and maximum possible item scores.

RESULTS

Study Participants

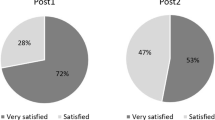

Table 1 provides detailed descriptive data for both the sample and the different PROs that were administered as a part of this study. Figure 2 includes a final.pdf version as well as scoring criteria for the REDD-CAT Housing Security.

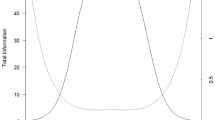

Housing Affordability Scale

Table 2 provides a summary of the analyses that supported the retention of the six final items in the Housing Affordability scale. Thresholds ranged from –1.73 to + 1.78 for the subdomain. There was good information (i.e., test information ≥ 5.0) for T-scores between 31 and 66 and acceptable information (test information ≥ 3.3) for T-scores between 26 and 71; marginal reliability was 0.84 for the 6-item measure. Table 3 provides the final characteristics for the new subdomain.

Housing Safety and Housing Features Indices Development

The Housing Safety subdomain is evaluated by a 3-item index, while the Housing Features subdomain is assessed by an 8-item index. The Housing Features index is generalized across differing discharge housing locations by referring respondents to, for example, “When I am discharged, the place I will go to.” Housing Safety and Housing Features scores are average item scores, which facilitate scoring and score interpretation when missing items occur.

Reliability and Validity Analyses

Housing Affordability

Internal consistency reliability of the REDD-CAT Housing Affordability subdomain was good, and it was devoid of floor and ceiling effects (Table 4). Convergent validity was supported (Table 5). Those persons with enough money to make ends meet (versus not enough money) reported less housing insecurity, supporting known-groups validity (Table 6). Logistic regression models indicated that Housing Affordability was one of seven variables that was related to readmission risk (i.e., the observed correlation of ≥ ± 0.15 with our risk level-dependent variable).

Housing Safety and Housing Features

Score distributions and the percentages of individuals with the highest and lowest scores are provided in Table 4. Convergent validity and discriminant validity was supported (Table 5). There was a trend (p < 0.07) for a significant difference between those with enough money to make ends meet to report less concern with housing safety relative to those without enough money to make ends meets (Table 6). All other known-groups analyses had results as were hypothesized (Table 6).

Anxiety About Affording Housing, Domestic Violence, and Anxiety About Where Will Sleep Next

Score distributions and the percentages of individuals with the highest and lowest scores are provided in Table 4 for these three single-item assessments.

DISCUSSION

This report describes the development of a new measure designed to capture important components of perceived Housing Security. This new measure, the REDD-CAT Housing Security PRO, captures three critical components of housing insecurity: Housing Affordability (6-item scale), Housing Safety (3-item index), and Housing Features (8-item index). To our knowledge, this PRO represents the first comprehensive measurement system of housing insecurity; it is both reliable and has good scale characteristics. There was also support for convergent and discriminant validity, as well as known-groups validity. Taken together, this new PRO has demonstrated that it is psychometrically sound; that is, the majority of our psychometric findings were in accordance with a priori hypotheses.58

The new Housing Security PRO includes two discharge housing location items, three distinct scale and index scores, and three single-item assessments. The first discharge housing location item, “When I am discharged, I will go to” has five response options, with respondent instructions to choose the best option: “my own home/family residence,” “a friend’s home/residence,” “a shelter,” “I do not have any options for housing or shelter,” and “I don’t know.” The second discharge housing location item, “With regard to my discharge” has nine response options, with respondent instructions to choose all options that apply; options are worded to elicit reasons for the anticipated discharge housing location (e.g., “because I need someone to take care of me” and “because I cannot afford independent housing”). Individuals that indicate a shelter, no options, or “I don’t know” should be flagged for additional follow-up to help ensure a safe housing placement at discharge.

Housing Affordability raw scores are converted to T-scores (using Table 5), with lower scores indicating more significant concerns with housing affordability. Interpretation of obtained Housing Affordability scores is as follows: (1) scores equal to or below 40 (i.e., ≤ 1 SD below the normative mean) indicate Housing Affordability concerns that exceed 83.9% of persons with T2DM; scores less than or equal to 30 (i.e., ≤ 2 SDs below the normative mean) indicate Housing Affordability concerns that are worse than 97.9% of persons with T2DM.

Housing Safety scores (i.e., the average score across completed items) range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater perceived safety. Additional follow-up is warranted for any average score that is less than 4. Housing Features scores (the average score across completed items) also range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more/more consistently present features of housing. Additional follow-up is warranted for any average score that is less than 4. Finally, any response other than “never” on the Anxiety About Affording Housing, Domestic Violence, or Anxiety About Where Will Sleep Next single-item assessments warrants clinical follow-up.

While this is the first measure designed to capture multiple domains of housing security, there are also several important limitations to our study. First, there are several limitations with regard to generalizability. For example, the new PRO was developed and tested in patients with T2DM; therefore, future testing is needed to determine if this measure will exhibit clinical utility in other populations. In addition, the study sample was recruited through an urban safety-net health system; findings may not be generalizable to other types of health systems. Furthermore, there were high rates of Black/African American patients and low rates of Hispanic/Latino patients in this study; more work is needed to ensure generalizability to other racial/ethnic groups. Second, while these data provide a preliminary look at reliability and validity, future work is needed in independent samples to confirm these findings and to examine the responsiveness of scores on this measure in the context of clinical follow-up. Third, while this tool is designed to screen for individuals that have housing insecurity, it is not yet designed to generate follow-up and appropriate referrals, the value of which warrants additional study. In addition, there is ongoing work examining the feasibility and acceptability of using the comprehensive REDD-CAT measurement system as part of the discharge planning process, which should be available in late 2023.

In sum, the new REDD-CAT Housing Security PROs is a psychometrically sound measure that can be used to identify individuals that are at high risk for negative outcomes due to housing insecurity. This measure, in combination with the broader REDD-CAT measurement system, provides a valuable tool for identifying unmet needs among persons with T2DM. It is our hope that this comprehensive measurement system for capturing important social determinants of health can provide an easy way to identify individuals at high risk for negative outcomes and provide them with appropriate referrals to help mitigate these unmet needs and ultimately maximize patient health-related quality of life.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, NEC, upon reasonable request.

References

D'Alessandro D, Appolloni L. Housing and health: an overview. Ann Ig. Sep-Oct 2020;32(5 Supple 1):17–26. https://doi.org/10.7416/ai.2020.3391

Shaw M. Housing and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:397-418. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123036

Anderst A, Hunter K, Andersen M, et al. Screening and social prescribing in healthcare and social services to address housing issues among children and families: a systematic review. Bmj Open. Apr 29 2022;12(4):e054338. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054338

Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. Tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2006–2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates using the Missouri Data Center MABLE/geocorr14. 2019. MANY HOUSEHOLDS BURDENED BY HOUSING COSTS IN 2019. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/son-2020-cost-burdens-map

Njai R, Siegel P, Yin S, Liao Y. Prevalence of Perceived Food and Housing Security - 15 States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jan 13 2017;66(1):12–15. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6601a2

Coakley KE, Cargas S, Walsh-Dilley M, Mechler H. Basic Needs Insecurities Are Associated with Anxiety, Depression, and Poor Health Among University Students in the State of New Mexico. J Community Health. Feb 6 2022;https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01073-9

Kim D. Financial hardship and social assistance as determinants of mental health and food and housing insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. SSM Popul Health. Dec 2021;16:100862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100862

Chen J, Hao S, Wu Y. Housing and health in vulnerable social groups: an overview and bibliometric analysis. Rev Environ Health. May 28 2021;https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2020-0167

Baker E, Lester L, Mason K, Bentley R. Mental health and prolonged exposure to unaffordable housing: a longitudinal analysis. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. Jun 2020;55(6):715-721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01849-1

Bassuk EL, Richard MK, Tsertsvadze A. The prevalence of mental illness in homeless children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. Feb 2015;54(2):86–96 e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.11.008

Marcal KE, Maguire-Jack K. Housing insecurity and adolescent well-being: Relationships with child welfare and criminal justice involvement. Child Abuse Negl. May 2021;115:105009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105009

Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income Americans. J Gen Intern Med. Jan 2006;21(1):71-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x

Mosley-Johnson E, Walker RJ, Thakkar M, et al. Relationship between housing insecurity, diabetes processes of care, and self-care behaviors. BMC Health Serv Res. Jan 13 2022;22(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07468-7

Berkowitz SA, Meigs JB, DeWalt D, et al. Material need insecurities, control of diabetes mellitus, and use of health care resources: results of the Measuring Economic Insecurity in Diabetes study. JAMA internal medicine. Feb 2015;175(2):257-65. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6888

Berkowitz SA, Kalkhoran S, Edwards ST, Essien UR, Baggett TP. Unstable Housing and Diabetes-Related Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalization: A Nationally Representative Study of Safety-Net Clinic Patients. Diabetes Care. May 2018;41(5):933-939. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-1812

Keene DE, Guo M, Murillo S. "That wasn't really a place to worry about diabetes": Housing access and diabetes self-management among low-income adults. Soc Sci Med. Jan 2018;197:71-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.051

Keene DE, Henry M, Gormley C, Ndumele C. 'Then I Found Housing and Everything Changed': Transitions to Rent-Assisted Housing and Diabetes Self-Management. Cityscape. 2018;20(2):107-118. https://doi.org/10.2307/26472170

Henry ML, Lichtman JH, Hanlon K, Keene DE. Clinical management of Type II Diabetes among the unstably housed: a qualitative study of primary care physicians. Fam Pract. Jul 23 2020;37(3):418-423. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmz085

Agardh E, Allebeck P, Hallqvist J, Moradi T, Sidorchuk A. Type 2 diabetes incidence and socio-economic position: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. Jun 2011;40(3):804-18. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr029

Stahre M, VanEenwyk J, Siegel P, Njai R. Housing Insecurity and the Association With Health Outcomes and Unhealthy Behaviors, Washington State, 2011. Preventing chronic disease. Jul 9 2015;12:E109. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.140511

Maty SC, James SA, Kaplan GA. Life-course socioeconomic position and incidence of diabetes mellitus among blacks and whites: the Alameda County Study, 1965-1999. Am J Public Health. Jan 2010;100(1):137-45. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.133892

Walker RJ, Smalls BL, Campbell JA, Strom Williams JL, Egede LE. Impact of social determinants of health on outcomes for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Endocrine. Sep 2014;47(1):29-48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-014-0195-0

Walker RJ, Gebregziabher M, Martin-Harris B, Egede LE. Understanding the influence of psychological and socioeconomic factors on diabetes self-care using structured equation modeling. Patient education and counseling. Jan 2015;98(1):34-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.10.002

Bernstein RS, Meurer LN, Plumb EJ, Jackson JL. Diabetes and hypertension prevalence in homeless adults in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. Feb 2015;105(2):e46-60. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302330

Axon RN, Gebregziabher M, Dismuke CE, et al. Differential Impact of Homelessness on Glycemic Control in Veterans with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Gen Intern Med. Nov 2016;31(11):1331-1337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3786-z

Lim S, Miller-Archie SA, Singh TP, Wu WY, Walters SC, Gould LH. Supportive Housing and Its Relationship With Diabetes Diagnosis and Management Among Homeless Persons in New York City. Am J Epidemiol. Jun 1 2019;188(6):1120-1129. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwz057

Carlozzi NE, Kallen M, Troost J, et al. Development and calibration data for the Medication Adherence Item Bank: A new computer adaptive test for persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Qual Life Res. In Press;doi:doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03275-z

Carlozzi NE, Kallen MA, Troost JP, et al. Development and calibration data for the Healthcare Access Item Bank: A new computer adaptive test for persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Qual Life Res. In Press; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03278-w

Mitchell S, Kallen MA, Troost JP, et al. Development and calibration data for the Illness Burden Item Bank: A new computer adaptive test for persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Qual Life Res. In Press;https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03282-0

Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. WRAT 4: wide range achievement test professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 2006.

PROMIS® Instrument Development and Psychometric Evaluation Scientific Standards. http://www.nihpromis.org/Documents/PROMIS_Standards_050212.pdf.

McDonald RP. Test theory: A unified treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1999.

Cook KF, Kallen MA, Amtmann D. Having a fit: Impact of number of items and distribution of data on traditional criteria for assessing IRT's unidimensionality assumption. Qual Life Res. May 2009;18(4):447-60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9464-4

Reise SP, Morizot J, Hays RD. The role of the bifactor model in resolving dimensionality issues in health outcomes measures. Qual Life Res. 2007;16 Suppl 1:19-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9183-7

Cancino R, Esang M, Martin J, Morton S, Kazis L, Jack B. Development of a Patient-Centered Instrument to Evaluate 30-Day Hospital Readmission. presented at: Academy Health; 2014; San Diego, CA. https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hub/235578/file-1091150256-pdf/PCORI_Poster.pdf?utm_campaign=2014-Summer+Newsletter&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=13294491&_hsenc=p2ANqtz--812aqVTW3C7ByHvanTeVb-yIllO1fWSKVJtPSnUwwSphSTyvyq4XWyvm2QqDIuJ3g_gYwfZvGTf8M_N4ZuOocZbiZcw&_hsmi=13294491

Tulsky DS, Kisala PA, Lai JS, Carlozzi N, Hammel J, Heinemann AW. Developing an item bank to measure economic quality of life for individuals with disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Apr 2015;96(4):604-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2014.02.030

Pilkonis PA, Yu L, Dodds NE, Johnston KL, Lawrence SM, Daley DC. Validation of the alcohol use item banks from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS((R))). Drug and alcohol dependence. Apr 1 2016;161:316-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.014

Pilkonis PA, Yu L, Dodds NE, et al. Item banks for substance use from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS((R))): Severity of use and positive appeal of use. Drug and alcohol dependence. Nov 1 2015;156:184-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.008

Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179-1194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011

Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. May 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3-S11. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55

Ruo B, Choi SW, Baker DW, Grady KL, Cella D. Development and validation of a computer adaptive test for measuring dyspnea in heart failure. J Card Fail. Aug 2010;16(8):659-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.03.002

Muraki E. Fitting a polytomous item response model to Likert-type data. Appl Psych Meas. 1990;14:59-71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014662169001400406

Clauser BE, Hambleton RK. Review of Differential Item Functioning, P. W. Holland, H. Wainer. J Educ Meas. 1994;31(1):88–92.

Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Muthén & Muthén; 2011.

TestGraf a program for the graphical analysis of multiple choice test and questionnaire data. McGill University; Aug 1, 2000. https://www.psych.mcgill.ca/misc/fda/downloads/testgraf/TestGraf98.pdf

Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, Second Edition. Guilford Press; 2005.

Bentler PM. Comparative Fit Indexes in Structural Models. Psychological Bulletin. Mar 1990;107(2):238-246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hatcher L. A step-by-step approach to using SAS for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. SAS Institute, Inc.; 1994.

Samejima F. Estimation of Latent Ability Using a Response Pattern of Graded Scores. Psychometrika. 1969;34(4p2):1-&.

Stark S, Chernyshenko OS, Drasgow F, Williams BA. Examining assumptions about item responding in personality assessment: should ideal point methods be considered for scale development and scoring? J Appl Psychol. Jan 2006;91(1):25-39. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.25

IRTPRO for Windows [Computer software]. Scientific Software International; 2015.

Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin. Mar 1959;56(2):81-105.

Andresen EM. Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. Dec 2000;81(12 Suppl 2):S15-20.

Cramer D, Howitt DL. The Sage disctionary of statistics. Sage; 2004.

Taylor R. Interpretation of the correlation coefficient: A basic review. Journal of Diagnostic and Medical Sonography. 1990;1:35-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/875647939000600106

Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor JT, Grant I. Revised comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian adults. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 2004.

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. Jan 2007;60(1):34-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

Acknowledgements:

Work on this manuscript was supported by grant number R21DK121092 (PIs Carlozzi; Mitchell [admin]) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) for the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (UL1TR002240). We thank the investigators and research associates who worked on the study, the study participants, and organizations who supported recruitment efforts. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Noelle E. Carlozzi: Principal investigator; data coordination and analysis site; analysis design; initial draft of introduction, methods, results, and discussion; incorporation of revisions.

Michael A. Kallen: Study co-investigator and statistician; assistance with analysis design; primary statistician for measurement development portions of manuscript (e.g., factor analyses and IRT analyses); drafted statistical analysis section and a template for the results section

Jonathan P. Troost: Statistician and data analyst; primary statistician for reliability and validity analyses; assistance writing methods and results sections; review and feedback on manuscript drafts

Jennifer A. Miner: Study data manager; critical review of the methods and results; review and feedback on manuscript drafts

Alexa Bragg: Study research coordinator; responsible for data collection; review and feedback on manuscript drafts (critical review of the methods)

Jessica Martin-Howard: Study grants manager and project coordinator; review and feedback on manuscript drafts; assistance with study regulatory documents

Barbara De La Cruz: Project manager; review and feedback on manuscript drafts; assistance with synthesis of revisions

Ioana Moldovan: Study research coordinator; responsible for data collection; review and feedback on manuscript drafts (critical review of the methods)

Brian W. Jack: Principal investigator of the PRET study; review and feedback on manuscript drafts (critical review of the summary of the qualitative work that informed this study)

Suzanne Mitchell: Principal investigator; data collection site; study design; critical review of the introduction and discussion; review and feedback on manuscript drafts

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval:

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Boston Medical Center, who served as the single IRB of record for this study. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate:

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in this study.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Carlozzi, N.E., Kallen, M.A., Troost, J.P. et al. Development of a New Measure of Housing Security: The REDD-CAT Housing Security Measure. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 2164–2178 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08147-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08147-x