Abstract

Background

While advanced care planning (ACP) is recommended in dementia and cancer care, there are unique challenges in ACP for individuals with dementia, such as the insidious onset and progression of cognitive impairment, potentially leading to high-intensity care at the end of life (EOL) for this population.

Objective

To compare ACP completion and receipt of high-intensity care at the EOL between decedents with dementia versus cancer.

Design

Retrospective longitudinal cohort study.

Participants

Participants of the U.S. Health and Retirement Study who died between 2000 and 2014 with dementia (n = 2099) and cancer (n = 1137).

Main Measures

Completion of three types of ACP (living will, durable power of attorney for healthcare [DPOAH], discussions of preferences for EOL care) and three measures of EOL care intensity (in-hospital death, intensive care unit [ICU] care in the last 2 years of life, life support use in the last 2 years of life).

Key Results

Use of living will was lower in dementia than in cancer (adjusted proportion, 49.9% vs. 56.9%; difference, − 7.0 percentage points [pp, 95% CI, − 13.3 to − 0.7]; p = 0.03). Use of DPOAH was similar between the two groups, but a lower proportion of decedents with dementia had discussed preferences compared to decedents with cancer (53.0% vs. 68.1%; − 15.1 pp [95% CI, − 19.3 to − 10.9]; p < 0.001). In-hospital death was higher in dementia than in cancer (29.5% vs. 19.8%; + 9.7 pp [95% CI, + 5.9 to + 13.5]; p < 0.001), although use of ICU care was lower (20.9% vs. 26.1%; − 5.2 pp [95% CI, − 9.8 to − 0.7]; p = 0.03). Use of life support was similar between the two groups.

Conclusions

Individuals with dementia complete ACP less frequently and might be receiving higher-intensity EOL care than those with cancer. Interventions targeting individuals with dementia may be necessary to further improve EOL care for this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

BACKGROUND

With the aging of the U.S. population, the number of individuals living with dementia is expected to grow from 6.2 million to 12.7 million by 2050.1 Dementia is a life-limiting illness and the sixth leading cause of death among all adults.2 Unlike most other life-limiting illnesses, dementia causes a gradual decline of thinking, remembering, and reasoning abilities, creating major challenges for patients, caregivers, and clinicians in providing appropriate care that is concordant with patients’ care preferences at the end of life (EOL).3,4,5

Existing literature suggests that advance care planning (ACP)—defined as a process of understanding and sharing personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future care6—may reduce unnecessary healthcare that does not align with patients’ care preferences.7,8 As a result, ACP has been gaining increasing attention from policymakers and insurers,7 and early ACP is recommended for individuals with dementia in professional guidelines, such as by the Alzheimer’s Association and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.9,10

The prevalence of ACP and the intensity of EOL care have been widely studied in cancer care.11,12,13,14 However, there have been concerns that the patterns of ACP use and EOL care in dementia care might differ from those in cancer care due to the decreased cognitive ability to participate in ACP conversations and difficulty in predicting the trajectory of the disease progression.15,16,17,18 Research has shown a lower ACP completion rate and similar intensity of EOL care for individuals with dementia compared to those with cancer. While informative, existing studies have been limited due to the use of narrowly focused populations (e.g., nursing home residents from one state,19 Veterans20), outdated data,21 or non-U.S. data.22 Moreover, to our knowledge, no study to date has examined whether the gaps between the two groups have changed over time. Given the growing prevalence of dementia in the U.S.A., it is critically important to understand how ACP use and EOL care differ between the two groups to inform future health policies.

To address this knowledge gap, we sought to compare the likelihood of ACP completion and its trend between decedents with dementia and those with cancer using a nationally representative sample of older adults in the U.S.A. We also compared the intensity of EOL care and its trend between the two groups.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Participants

We used the data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative longitudinal survey of adults aged 51 years and older.23 The HRS participants undergo “core” interviews every 2 years until death that collect information about demographics, physical and cognitive function, and medical conditions.23 After each participant’s death, a proxy (such as a widow or widower) undergoes an “exit” interview that collects information of the deceased, including the physical and mental health and healthcare utilization.24 The response rates of HRS are consistently above 80%.25

Among all the HRS decedents from the 2002–2014 exit interviews, we identified two groups: (i) decedents with dementia (dementia group) and (ii) decedents with a cancer diagnosis (cancer group). We assigned a decedent to the dementia group if the probability of dementia was greater than 50% that is provided by HRS researchers for each HRS participant 70 years and older reporting to be non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Hispanic.26 The probability of dementia is calculated based on a validated prediction model using the information from the latest core interviews (typically within 2 years before the death), such as activities of daily living and multiple cognitive batteries (e.g., backward counting from 20, immediate and delayed word recall).27 A cut-off of 50% has been reported to classify 88% of participants correctly and used in previous literature.28,29 We assigned a decedent to the cancer group if the proxy-reported cause of death was cancer.

We compared these two groups (i.e., those who died with dementia vs. those who died of cancer) because they are similar in that ACP was indicated. In cancer care, there is often time to anticipate EOL care planning needs facing disease progression (typically a few months before death),18 whereas a diagnosis of dementia should trigger ACP given the progressive cognitive impairment. In addition, very few proxies reported dementia as the cause of death among the dementia group (see Appendix Table 1 for more details). We excluded decedents if (i) they have missing data on adjustment variables or zero-weights (n = 46) or (ii) the probability of dementia was greater than 50% and cancer was listed as a cause of death (n = 194). See Appendix Figure 1 for a flow chart.

Advance Care Planning Measures

Based on proxy reports, we used three binary variables to measure the completion of three types of ACP: (i) “Living Will” (the participant’s provision of written instructions for EOL care); (ii) “Durable Power of Attorney for Healthcare” (DPOAH, a legal arrangement for a specific person or persons to make decisions about medical care if the participant cannot make those decisions); and (iii) “Discussions of Preferences” (the participant’s engagement in discussions with anyone prior to death about preferences for EOL care). See Appendix Methods for the exact wording of these questions.

End-of-Life Care Intensity Measures

Based on proxy reports, we used three binary variables to measure EOL care intensity: (i) “in-hospital death” (whether a participant died in a hospital); (ii) “ICU care” (whether a participant spent time in an intensive care unit [ICU] in the last 2 years of life); and (iii) “life support use” (whether a participant used life support equipment [e.g., mechanical ventilation] in the last 2 years of life). See Appendix Methods for the exact wording of these questions.

Adjustment Variables

We included the following variables in our regression models as adjustment variables (data was obtained from the exit interview or the latest available core interviews): age at death (as continuous), race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Hispanic), sex, marital status (married or not married), education attainment (less than high school, graduated high school/general equivalency diploma, or at least some college), whether a participant was living in a nursing home at the time of death, wealth categorized in quartiles (defined as the net value of total wealth including secondary residence less all debt), whether a participant was covered by Medicaid at the time of death, dummy variables for each of the six comorbidities (heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, lung disease, arthritis, stroke), a functional limitation score defined as the number of activities of daily living (ADL) requiring assistance during the last 3 months of life (categories of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6, 6 indicating that a participant required assistance in walking, toileting, bathing, transferring, eating, and dressing),30 geographic location of death (categorized into nine census divisions and foreign county), and year of death (fixed effects; i.e., categorical).

Statistical Analysis

First, we estimated multivariable linear regression models to examine the association between dementia status (vs. cancer) and each of the three ACP completion measures, along with the adjustment variables. We used linear regression models as opposed to logistic regression models for the interpretability of the regression coefficients (i.e., linear probability models). Second, we examined whether the time trends in ACP completion measures differed between dementia and cancer groups. To do so, we first estimated multivariable linear regression models to evaluate the association between year of death (as continuous, instead of categorical, variables in the main analysis) and each outcome (three ACP measures) for dementia and cancer groups separately (i.e., testing whether there was a significant linear trend in each group). We then estimated p values for the interaction terms between the year of death (as continuous) and dementia status (vs. cancer) using the total sample to formally test whether the time trends in the two groups were different. We conducted similar analyses for the three EOL care intensity measures.

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted a series of additional analyses. First, to test the sensitivity of our findings to the time frame of EOL care (i.e., 2 years), we limited our sample to those who died within 1 year of the last HRS core interview, effectively examining ICU care and life support use in the last year of life. Second, we reanalyzed the data with an alternative model specification by not including functional limitation score and nursing home status in the regression models because these may be correlated with dementia status. Lastly, we examined four alternative ACP completion measures defined by the completion of two or three ACP components (e.g., both living will and DPOAH) to further understand the patterns of ACP completion. We also conducted similar analyses using four alternative EOL care intensity measures defined by the receipt of two or three high-intensity EOL care.

All analyses accounted for the complex survey design of HRS to account for nonresponse and produce national estimates.31 Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 and Stata version 14.2 with two-sided tests and a significance level of 0.05. This study was deemed exempt by the Cedars-Sinai Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Decedents with dementia (n = 2099) were older, less likely to be male, non-Hispanic whites, and married, and had less education and wealth, compared to decedents with cancer (n = 1137) (Table 1). Decedents with dementia were also more likely to be covered by Medicaid, live in a nursing home, and have more comorbidities and functional limitations.

Main Analysis: ACP Completion by Dementia Status (Vs. Cancer)

We found that the likelihood of having a living will was lower in the dementia group compared to the cancer group (adjusted proportion, 49.9% for dementia vs. 56.9% for cancer; adjusted difference, − 7.0 percentage points [pp, 95% CI, − 13.3 to − 0.7]; p = 0.03) (Table 2). There was no evidence that the likelihood of assigning DPOAH differed between the two groups. The likelihood of engaging in discussions of preferences was lower in the dementia group compared to the cancer group (53.0% vs. 68.1%; − 15.1 pp [95% CI, − 19.3 to − 10.9]; p < 0.001).

Time Trends in ACP Completion by Dementia Status (Vs. Cancer)

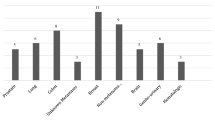

The likelihood of assigning DPOAH has increased in the dementia group (from 56.3% in 2000 to 75.4% in 2014; P-for-trend < 0.001), similarly to the cancer group (from 51.9% in 2000 to 68.7% in 2014; P-for-trend = 0.02) (Fig. 1). We found no evidence that the likelihood of having a living will or discussions of preferences has changed over time in the dementia group, while the likelihood of discussions of preferences has increased in the cancer group. There was no evidence that the trends in ACP measures differ between the two groups.

Adjusted yearly proportions of ACP completion among decedents with dementia vs. cancer. Data shown are adjusted proportions of decedents with dementia and cancer who completed ACP based on the Health and Retirement Study Exit Interview data 2002–2014. See Appendix Methods in the Supplementary Appendix for the exact wording of ACP completion measures. Abbreviations: ACP, advance care planning; EOL, end of life.

Main Analysis: EOL Care Intensity by Dementia Status (Vs. Cancer)

We found that the likelihood of in-hospital death was higher in the dementia group compared to the cancer group (29.7% vs. 19.8%; + 9.7 pp [95% CI, + 5.9 to + 13.5]; p < 0.001), although the likelihood of receiving ICU care was lower in the dementia group than in the cancer group (20.9% vs. 26.1%; − 5.2 pp [95% CI, − 9.8 to − 0.7]; p = 0.03) (Table 3). There was no evidence that the likelihood of life support use differed between the two groups.

Time Trends in EOL Care Intensity by Dementia Status (Vs. Cancer)

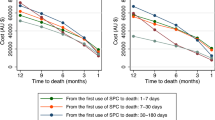

There was a decreasing trend in in-hospital death in both dementia and cancer groups, while there was no evidence that the likelihood of receiving ICU care or life support in the last 2 years of life has changed over time in either group (Fig. 2). We found no evidence that the trends in EOL care intensity differed between the two groups.

Adjusted yearly proportions of EOL care intensity among decedents with dementia and cancer. Data shown are adjusted proportions of decedents with dementia who received high-intensity care at the EOL care based on the Health and Retirement Study Exit Interview data 2002–2014. See Appendix Methods in the Supplementary Appendix for the exact wording of EOL care intensity measures. Abbreviations: EOL, end of life; ICU, intensive care unit.

Sensitivity Analyses

Our sensitivity analyses using an alternative study population (limiting our sample to those who died within 1 year of the last HRS core interview) and model specification (not including functional limitation score and nursing home status in the regression models) yielded similar findings to the main analysis (Appendix Tables 2 through 4). Analyses using the four alternative ACP completion measures suggest that less than 50% of participants completed two or three components of ACP in both groups, and the likelihoods of completing these ACP components were significantly lower in the dementia group than in the cancer group (Appendix Table 5). Similarly, analyses using the four alternative EOL care intensity measures suggest that few participants experienced two or more high-intensity EOL care in both groups, and the likelihoods of receiving these treatments were not significantly different between the two groups (Appendix Table 6).

DISCUSSION

Using nationally representative data from HRS, we found that decedents with dementia were less likely to have completed ACP prior to death compared to decedents with cancer. We also found that decedents with dementia were less likely to have used ICU in the last 2 years of life compared to those with cancer but more likely to have died in hospital. Additionally, only two-thirds or less completed ACP and about a quarter received high-intensity EOL care in both groups, and there was no evidence that the trends in ACP completion and EOL care intensity differed between the two groups between 2000 and 2014. Taken together, our findings indicate that, at the population level, a diagnosis of dementia was associated with a lower uptake of ACP while improving, and individuals with dementia might be receiving higher intensity of EOL care compared to those with cancer. Interventions to promote ACP targeting specifically individuals with dementia may be warranted to reduce care that does not align with patients’ care preferences among this population.

Our finding that individuals with dementia complete ACP less frequently may be attributable to unique barriers in dementia care, such as the tendency to delay ACP completion due to the gradual onset and progression of dementia, not being aware of the trajectory of dementia (median survival from initial diagnosis of 5 years32), and underdiagnosis of dementia.17,33 However, this gap may be narrowing over time as our trend analysis indicates that the likelihood of assigning DPOAH among individuals with dementia has increased in recent years. The growing body of evidence has shown the benefits of ACP for individuals with dementia, and the development of clinical guidelines recommending early ACP in dementia care might be contributing to this increased uptake of DPOAH assignment among this population.34 In addition, while the tests of the trend for living will and discussions of preferences were not statistically significant, the upward trend evident in the figures suggests that further studies with a larger sample size are warranted. Yet, we observed a persistent disparity in discussions of preferences for EOL care between the two groups, and a specific intervention that promotes early ACP discussions in dementia care might be required.

We found that the likelihood of in-hospital death was higher in the dementia group than in the cancer group. However, individuals with dementia were less likely to use ICU care in the last 2 years of life compared to those with cancer. These may be explained by the different disease trajectories of dementia and cancer. Individuals with dementia have a low baseline of cognitive and physical function, and the disability progresses slowly.18 Therefore, families may choose not to provide ICU-level care but be hesitant to decide to transition to comfort-oriented care due to perceived prognostic uncertainty.35,36,37 This is in contrast to individuals with cancer, who often have a high level of function at baseline, exhibit a gradual decline initially, and then later experience a relatively rapid decline at the EOL.18 As a result, the need for a transition to comfort-oriented care is typically evident. Our findings suggest that the likelihoods of in-hospital death are declining in both groups; the potential mechanisms include more prevalent ACP and increased availability of hospice care in various care settings.38

Our study builds upon previous work that compared ACP completion and EOL care intensity between individuals with dementia and cancer. One study examined data of nursing home residents in New York State and reported a lower ACP completion rate among individuals with dementia than among those with cancer.19 Another study showed that Veterans with dementia died in a hospital as often as those with cancer did.20 A similar study found that Medicare beneficiaries with dementia received similar intensity of EOL care (e.g., ICU use and mechanical ventilation in the last 30 days of life) compared to those with cancer in 2009.21 Lastly, a study conducted in Taiwan found that individuals with dementia received higher-intensity EOL care (e.g., ICU use and mechanical ventilation in the last year of life) than those with cancer.22 However, these studies are limited in that they examined specific populations,19,20 used outdated data,21 or were conducted outside of the U.S.A.22 In addition, no study to date has examined whether the trends in ACP completion and EOL care intensity differ in individuals with dementia and cancer. We provide new evidence on the difference in ACP completion and EOL care intensity between the two groups using a U.S. nationally representative sample.

Our study has limitations. First, although proxy reports are commonly seen as valid and reliable measures and widely used in prior studies,7,39 these may be affected by the potential recall and social desirability biases. In addition, we were not able to capture the information that proxies were not aware of. Second, our study was not able to determine whether in-hospital death, ICU care, or life support use was or was not aligned with patients’ care preferences. Although HRS asks proxies about the care preference specified in the living wills, we were unable to analyze this outcome given the small sample size. Future larger studies are warranted. Third, we used the time frame of 2 years to evaluate EOL care intensity (ICU care and life support use) because the data using a shorter time frame that may be more common in existing literature (e.g., last year of life) was not available in HRS. However, our sensitivity analysis restricting to individuals who died within 1 year of the last HRS core interview showed similar results, supporting the validity of our findings. Fourth, we were not able to account for the type or severity of dementia or cancer because HRS (or the prediction model for dementia) does not provide the information. Lastly, as the probability of dementia was calculated for limited HRS participants (i.e., 70 years and older with self-reportedrace/ethnicity of non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Hispanic) and we included only those with non-missing data on this variable, our findings may not be generalizable to other populations (e.g., younger populations).

In summary, using a nationally representative sample of older adults, we found that individuals with dementia were less likely to complete ACP compared to those with cancer, although this gap may have been closing in the last decade. We also found that individuals with dementia were more likely to die in hospital compared to those with cancer, but the greater likelihood of death in hospital has been declining over time. Interventions targeting individuals with dementia may be needed to further improve EOL care for this growing population.

References

Alzheimer’s Association. 2021 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. 2021; https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2021.

Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2018. 2020; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db355.htm. Accessed April 16, 2020.

Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The Clinical Course of Advanced Dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1529-1538.

Mitchell SL, Morris JN, Park PS, Fries BE. Terminal care for persons with advanced dementia in the nursing home and home care settings. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(6):808-816.

Cai S, Gozalo PL, Mitchell SL, et al. Do patients with advanced cognitive impairment admitted to hospitals with higher rates of feeding tube insertion have improved survival? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(3):524-533.

Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition From a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):821-832.e821.

Silveira MJ, Kim SYH, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211-1218.

Bischoff KE, Sudore R, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Smith AK. Advance care planning and the quality of end-of-life care in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):209-214.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. 2018; https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97/chapter/Recommendations#palliative-care. Accessed June 15, 2021.

Alzheimer’s Association. Dementia Care Practice Recommendations. 2018; https://www.alz.org/professionals/professional-providers/dementia_care_practice_recommendations. Accessed June 15, 2021.

Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Approximately one in three us adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Affairs. 2017;36(7):1244-1251.

Luta X, Maessen M, Egger M, Stuck AE, Goodman D, Clough-Gorr KM. Measuring intensity of end of life care: a systematic review. PloS one. 2015;10(4):e0123764-e0123764.

Lastrucci V, D'Arienzo S, Collini F, et al. Diagnosis-related differences in the quality of end-of-life care: A comparison between cancer and non-cancer patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204458.

Foley KM, Gelband H. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer: Summary and Recommendations. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

Gaster B, Larson EB, Curtis JR. Advance Directives for Dementia: Meeting a Unique Challenge. JAMA. 2017;318(22):2175-2176.

Span P. One Day Your Mind May Fade. At Least You’ll Have a Plan. The New York Times. January 19, 2018.

Dening KH, Sampson EL, De Vries K. Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. Palliat Care. 2019;12:1178224219826579.

Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. Bmj. 2005;330(7498):1007-1011.

Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying With Advanced Dementia in the Nursing Home. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(3):321-326.

Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of End-of-Life Care Provided to Patients With Different Serious Illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1095-1102.

Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. Jama. 2013;309(5):470-477.

Chen YH, Ho CH, Huang CC, et al. Comparison of healthcare utilization and life-sustaining interventions between elderly patients with dementia and those with cancer near the end of life: A nationwide, population-based study in Taiwan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(12):2545-2551.

Health and Retirement Study. The Health and Retirement Study. 2019; https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/about. Accessed June 9, 2020.

Health and Retirement Study. HEALTH AND RETIREMENT STUDY 2016 Exit: Data Description and Usage. 2018; http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/2016/exit/desc/x16dd.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2020.

Health and Retirement Study. HRS: Sample Sizes and Response Rates. 2017; https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/biblio/ResponseRates_2017.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2020.

Health and Retirement Study. Gianattasio-Power Predicted Dementia Probability Scores and Dementia Classifications. 2020; https://hrsdata.isr.umich.edu/data-products/gianattasio-power-predicted-dementia-probability-scores-and-dementia-classifications. Accessed January 27, 2021.

Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1326-1334.

Gianattasio KZ, Ciarleglio A, Power MC. Development of Algorithmic Dementia Ascertainment for Racial/Ethnic Disparities Research in the US Health and Retirement Study. Epidemiology. 2020;31(1).

Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):729-736.

Fonda S, Herzog AR. Documentation of Physical Functioning Measured in the Heath and Retirement Study and the Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old Study 2004; https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/biblio/dr-008.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2021.

Health and Retirement Study. Sampling Weights: Revised for Tracker 2.0 and Beyond. 2019; https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/biblio/wghtdoc_0.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2020.

Larson EB, Shadlen MF, Wang L, et al. Survival after initial diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(7):501-509.

Lingler JH, Hirschman KB, Garand L, et al. Frequency and correlates of advance planning among cognitively impaired older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(8):643-649.

van der Steen JT. Dying with dementia: what we know after more than a decade of research. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(1):37-55.

Harris D. Forget me not: palliative care for people with dementia. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(980):362-366.

Ahronheim JC, Morrison RS, Morris J, Baskin S, Meier DE. Palliative care in advanced dementia: a randomized controlled trial and descriptive analysis. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(3):265-273.

Martinsson L, Lundström S, Sundelöf J. Quality of end-of-life care in patients with dementia compared to patients with cancer: A population-based register study. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0201051.

Cross SH, Kaufman BG, Taylor DH, Jr., Kamal AH, Warraich HJ. Trends and Factors Associated with Place of Death for Individuals with Dementia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(2):250-255.

Silveira MJ, Wiitala W, Piette J. Advance directive completion by elderly Americans: a decade of change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):706-710.

Acknowledgements

Contributors: We thank Mourad Tighiouart, PhD, for statistical advice.

Funding

This study was supported by Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Clinical and Translational Science Institution (CTSI) Clinical Scholar Grant (Dr. Gotanda) and by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01AG068633 (Dr. Tsugawa). Dr. Tsugawa was supported by NIH/NIMHD Grant R01MD013913 for other work not related to this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations This study has never been presented.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 91 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gotanda, H., Nuckols, T.K., Lauzon, M. et al. Comparison of Advance Care Planning and End-of-Life Care Intensity Between Dementia Versus Cancer Patients. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 3251–3257 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07330-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07330-2