Abstract

Background

In 2012, the Ministry of Health in British Columbia, Canada, introduced a $75 incentive payment that could be claimed by hospital physicians each time they produced a written post-discharge care plan for a complex patient at the time of hospital discharge.

Objective

To examine whether physician financial payments incentivizing enhanced discharge planning reduce subsequent unplanned hospital readmissions.

Design

Interrupted time series analysis of population-based hospitalization data.

Participants

Individuals with one or more eligible hospitalizations occurring in British Columbia between 2007 and 2017.

Main Measures

The proportion of index hospital discharges with subsequent unplanned hospital readmission within 30 days, as measured each month of the 11-year study interval. We used interrupted time series analysis to determine if readmission risk changed after introduction of the incentive payment policy.

Key Results

A total of 40,588 unplanned hospital readmissions occurred among 409,289 eligible index hospitalizations (crude 30-day readmission risk, 9.92%). Policy introduction was not associated with a significant step change (0.393%; 95CI, − 0.190 to 0.975%; p = 0.182) or change-in-trend (p = 0.317) in monthly readmission risk. Policy introduction was associated with significantly fewer prescription fills for potentially inappropriate medications among older patients, but no improvement in prescription fills for beta-blockers after cardiovascular hospitalization and no change in 30-day mortality. Incentive payment uptake was incomplete, rising from 6.4 to 23.5% of eligible hospitalizations between the first and last year of the post-policy interval.

Conclusion

The introduction of a physician incentive payment was not associated with meaningful changes in hospital readmission rate, perhaps in part because of incomplete uptake by physicians. Policymakers should consider these results when designing similar interventions elsewhere.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT03256734

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Unplanned hospital readmissions are common, costly and associated with adverse outcomes.1 About 10% of hospitalized Canadians undergo unplanned readmission within 30 days of discharge, resulting in $2.1 billion CAD in additional health system costs each year.2 One in five patients die within 30 days of readmission, a risk threefold greater than among non-readmitted patients.3,4 In response to these striking statistics, clinicians, administrators and researchers have spent over a decade seeking ways to prevent unplanned hospital readmissions.

Important gaps in transitional care are believed to contribute to unplanned hospital readmissions. One-third of discharged patients have no physician follow-up within 14 days, and only 50% of readmitted patients visit primary care before returning to hospital.5,6,7 Only 60% of hospitalized older adults can correctly state their discharge diagnosis, yet discharge summaries are commonly unavailable at the first post-discharge primary care follow-up visit.8,9 These communication gaps heighten readmission risks.10 Up to 62% of test results that are unavailable at the time of discharge are never reviewed by a physician.11 Preventable adverse drug events (including unintentional medication discontinuation) are common after hospitalization and may prompt hospital readmission.12,13,14 The pervasiveness of these shortcomings suggests some readmissions might be avoided by encouraging early clinical follow-up, expedited communication between hospital and community clinicians, enhanced patient understanding and improved discharge medication reconciliation.

Policymakers have attempted to address unplanned hospital readmissions using financial incentives. The US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program incentivizes improved transitional care by withholding up to 3% of reimbursements to hospitals with unexpectedly high 30-day readmission risks.15 However, in contrast to outcome-focused hospital-level penalties, the effectiveness of process-focused physician-level incentive payments is less well established. For example, a $25 CAD payment to primary care physicians in the Canadian province of Ontario encouraged follow-up within 14 days of hospital discharge and was associated with annual expenditures of $2.1M CAD but produced no significant improvement in early follow-up, hospital readmission or death.5 Incentives payments to US primary care clinicians for enhanced transitional care management may have reduced mortality and cost, but population impact has been severely limited by extremely low uptake.16 Physician financial incentives have remained appealing to policymakers and clinicians despite other studies suggesting a limited impact on outpatient visits or preventative care.17,18,19,20,21,22

On June 1, 2012, policymakers in British Columbia introduced a fee-for-service physician payment claim code that was intended “to support clinical coordination leading to effective discharge and community-based management of complicated patients...at risk of readmission.”23 The incentive payment could be claimed on the day of hospital discharge and was designed to encourage hospital physicians to provide the patient and their primary care provider with a written care plan within 24 h of discharge. To address some modifiable contributors to readmissions, the care plan was designed to ensure patients understood their diagnosis; ensure patients had contact information for their primary care physician; remind physicians to reconcile discharge medications; remind physicians to arrange appropriate follow-up care; and improve overall discharge communication between hospital physicians, patients and primary care providers. In practice, written care plans were typically created separately and in advance of the discharge summary, faxed to the primary care provider just prior to the patient’s departure from hospital, and subsequently incorporated into the hospital paper medical record. Successful claims resulted in a $75 payment to the physician in addition to payments for routine day-of-discharge hospital care.

In light of the uncertainty effectiveness of physician financial incentives as a tool to improve population health, we sought to test whether the introduction of BC’s incentive payment policy was associated with a reduction in the risk of unplanned hospital readmission.

METHODS

Setting

We performed a population-based interrupted time series analysis of hospitalizations in British Columbia (BC), a Canadian province of 4.6 million residents. Over the 11-year study interval, universal health insurance provided BC residents with access to hospital and physician care that was free at the point of service.24 Most specialist physicians were remunerated by the provincial government on a fee-for-service basis.25 The fee code of interest (“G78717”; Appendix, Item SA1) was developed by the Specialist Services Committee (SSC), a partnership between the BC Ministry of Health and Doctors of BC (the professional association representing physicians) with a mandate to “identify changes in current physician service delivery that could result in improvements in patient care ... and measurable savings.”26

All larger and most small hospitals had electronic health records (EHRs) that included laboratory test results, radiology reports, initial physician consultation notes and hospital discharge summaries. Daily progress notes, nursing notes, allied health records and comprehensive discharge planning documents were typically excluded from the EHR and were instead part of a paper-based health record. Access to hospital records by primary care clinics and unaffiliated hospitals was variable, incomplete and cumbersome (often involving transmission by fax machine). Hospital-based discharge planning typically involved multiple weekly meetings between the physician, nurse leader, occupational and physical therapists, pharmacist, social worker and a transitional services team liaison to assist with initiation of community home care services.

Data

De-identified individual-level longitudinal data were obtained from population-based administrative databases used extensively in prior research (Item SA2).27 Data on hospitalizations were obtained from the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD).28 These were linked to other administrative databases to obtain patient demographics, residential neighborhood income quintile, and comorbidities derived from the diagnostic fields of hospitalization and clinic visits in the year prior to index hospitalization (Item SA3).29,30,31 Baseline prescription medication fills were assessed in the 90 days prior to index admission date and in the 60 days following index discharge date using PharmaNet, a provincial database capturing all outpatient prescriptions filled in a community pharmacy in BC.32 Neighbourhood income quintile was missing for 6.6% of the cohort but data were otherwise complete.

Study Cohort

The study population was comprised of all adults discharged from an acute care hospital in BC between April 1, 2007, and January 31, 2017. We excluded hospitalizations for individuals aged <18 years at the time of discharge and those with a Most Responsible Diagnosis corresponding to pregnancy, childbirth, or the puerperal and perinatal periods. We set index hospital admissions as the unit of analysis and individual patients could contribute multiple hospital admissions to the study.

Index hospital admissions were included in the primary analysis if they met the initial 2012 eligibility criteria for the incentive payment: (1) a most responsible provider (MRP) that was a specialist physician; (2) an “admission category” designation of “urgent” (rather than “elective”) and (3) a “total length of stay” (LOS) ≥5 days. Hospitalizations were ineligible as index admissions if the admission date occurred within 30 days of a prior hospital discharge date or if they ended in discharge against medical advice or death.

Primary Analysis

Our primary analysis used interrupted time series analysis to test the hypothesis that the introduction of the incentive payment policy was associated with a change in the risk of unplanned hospital readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge. We selected an interrupted time series approach in order to assess the influence of the policy on population-level hospital readmission risks. This approach also avoids bias arising from treatment selection and residual confounding that might limit a study comparing outcomes among G78717 exposed patients and unexposed patients. We aggregated index discharge dates by calendar month and categorized months as belonging to the pre-policy period (April 1, 2007, to May 31, 2012) or the post-policy period (June 1, 2012, to January 31, 2017). Our primary analysis used an autoregressive model with maximum likelihood estimation to account for trends in the monthly hospital readmission risk, with separate regression terms describing the step change and slope change occurring at the transition from the pre- to the post-policy period. Heteroscedasticity was assessed using SAS’s ARCHTEST function. Autocorrelation was assessed using the Durbin-Watson statistic. Stationarity was assessed using the Auto Correlation Function and Partial Auto Correlation Function. Seasonality was evaluated by examining scatterplots of the time series data. We assessed model fit using studentized residuals, the normality of the residuals and white noise probabilities. We used Cook’s distance to identify outliers in the data.33

Additional Analyses

Sensitivity analyses examined the influence of clustering within hospital. Secondary analyses evaluated the appropriateness of post-discharge medication prescription fills because unplanned hospital readmissions can be a consequence of under-prescription of indicated medications or over-prescription of unnecessary medications.13,34,35 We focused on two commonly prescribed classes of medication with compelling indications for use in clearly-defined populations. For index admissions for cardiovascular disease (acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, or chronic ischemic heart disease), we calculated the proportion receiving at least one prescription fill for specific beta-blocking drugs (bisoprolol, carvedilol, or metoprolol) within 60 days of index hospital discharge. We interpreted a higher prevalence of beta-blocker prescription fills as an improvement in the quality of medical care (Item SA4).36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49 For index admissions among patients aged 65 years or older, we calculated the proportion with at least one prescription fill for a potentially inappropriate medication (PIM).50 We interpreted a lower prevalence of these medications as an improvement in the quality of medical care.50,51,52,53,54,55,56

We analyzed the net spending benefit of the incentive payment policy in the post-policy period by comparing the government’s expected spending on readmissions with actual spending on the new fee code. We calculated the projected number of avoided readmissions in each month by subtracting the observed number of readmissions from the expected number of readmissions. We estimated the expected number of readmissions by multiplying the number of index admissions in that month by the “no policy” counterfactual readmission risk calculated for that month using the pre-policy interval regression equation. We estimated the cumulative cost savings resulting from the policy's influence on readmissions by multiplying the estimated number of avoided readmissions by hospital unit costs (cost per weighted case) provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and patients’ Resource Intensity Weight (a measure of total patient resource use relative to average acute inpatient resource use).57 We estimated the cumulative cost of the intervention by multiplying the number of incentive payment claims by payment cost ($75). We calculated the net cost of the intervention by subtracting the cumulative cost of the intervention from the cumulative cost savings resulting from the intervention.

Ethics

The University of British Columbia Clinical Research Ethics Board approved the study and waived the requirement for individual consent (H17-01039). A study protocol was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03256734). Statistical analyses used 2-sided tests and significance was inferred from p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 and R version 4.0.4. Data analysis occurred from October 2018 to February 2020. All inferences, opinions and conclusions drawn in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the Data Steward(s). The Specialist Services Committee and the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute funded the study but were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data or preparation, review and approval of this manuscript.

RESULTS

The final study cohort included a total of 290,498 unique individuals with 409,289 index hospitalizations resulting in 40,588 (9.92%) unplanned readmissions within 30 days of index discharge (Fig. 1). Advanced age, multimorbidity and polypharmacy at the time of index hospital admission were common. About 19% of index hospitalizations included a stay in the intensive care unit and 45% had a total length of stay ≥10 days (Table 1). A total of 6476 unique individual specialist most responsible providers supervised index hospitalizations eligible for the incentive payment and 1178 (18.2%) of these physicians claimed one or more incentive payments. Most claims were submitted by specialists in psychiatry and general internal medicine (Items SA5 and SA6). Uptake of incentive payment claims by physicians was gradual and incomplete, rising from 6.4 to 23.5% of eligible hospitalizations between the first and last year of the post-policy interval (Item SA7). Most physicians only claimed G78717 for a small proportion of eligible hospitalizations (Item SA8).

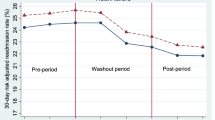

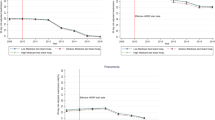

Interrupted time series analysis indicated the introduction of the incentive payment policy was not associated with a change in the risk of unplanned readmission (step change after policy introduction, 0.393%; 95%CI, −0.190 to 0.976%; p = 0.182; slope change after policy introduction, 0.00879% per month, 95%CI, −0.00857 to 0.0261% per month; p = 0.317; Table 2; Fig. 2). Similarly, the introduction of the incentive payment policy was not associated with a reduction in mortality within 30 days of index discharge, nor with improvements in beta-blocker prescription fills after hospitalization for cardiovascular disease (Fig. 3; Item SA9). In contrast, significant improvements in post-discharge prescription fills for potentially inappropriate medication among patients aged ≥65 years occurred in association with the introduction of the incentive payment policy (from 33% in June 2012 to 25% in January 2017).

Interrupted time series of unplanned hospital readmissions and deaths within 30 days of index discharge. Legend: Interrupted time series evaluating the influence of the introduction of the incentive payment policy on 30-day readmission rate and 30-day mortality rate. X-axis indicates the month of index hospital discharge. Y-axis indicates the proportion of index hospitalizations with the specified outcome within 30 days of discharge. Black circular points depict the observed monthly readmission rate. Blue diamond points indicate the observed monthly death rate. Gold vertical line indicates the policy introduction on June 1, 2012. Red lines depict the interrupted time series regression model describing risks before and after the introduction of the policy. Dashed grey lines depict the counterfactual (predicted) risks in the absence of the policy. Main finding is that the introduction of the policy was associated with no significant step or slope change in risk of unplanned readmission or in risk of death.

Interrupted time series analysis of post-discharge prescription quality-of-care. Legend: Interrupted time series evaluating the influence of the introduction of the policy on the prevalence of specific prescription medication fills within 60 days of index hospital discharge. X-axis indicates the month of index hospital discharge. Gold vertical line indicates the introduction of the policy on June 1, 2012. Y-axis indicates the prevalence of specific prescription medication fills within 60 days of index hospital discharge. Purple points depict the observed prevalence of prescription beta-blocker fills within 60 days of index discharge following hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, or chronic ischemic heart disease (Canadian Institute of Health Information Case Mix Group categories 1012, 1013, and 1015, respectively). Dark green points depict the observed prevalence of prescription fills for potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) within 60 days of index discharge among patients aged ≥65 years. Light green points depict the observed prevalence of prescription fills for benzodiazepines or non-benzodiazepine hypnotics (a subset of PIMs) within 60 days of index discharge among patients aged ≥65 years. Red line depicts the interrupted time series regression model for each medication group. Dashed grey line depicts the counterfactual (predicted) prescription fill prevalence in the absence of the policy. Main finding is that the introduction of the policy was associated with no significant step or slope change in beta-blocker prescriptions among patients with index cardiovascular admission but a significant reduction in PIMs and the subset of PIMs that include only benzodiazepines or non-benzodiazepine hypnotics.

Although the introduction of the incentive payment policy was not associated with a significant change in the risk of unplanned readmission, we used the difference between observed and expected readmissions to generate best estimates for the potential impact of the policy on readmissions and costs (Table 3). The incentive payment policy was not associated with a significant reduction in the risk of unplanned hospital readmission in any major subgroup (Item SA10). Sensitivity analyses accounting for hospital-level effects also suggested policy introduction was not associated with changes in readmission risks (Item SA11). Supplementary analyses suggested no substantial change in the proportion of patients discharged home (as opposed to long-term care) over the study interval (Item SA12).

DISCUSSION

We performed a population-based interrupted time series analysis of non-elective hospital admissions in British Columbia over an 11-year study interval and found that the introduction of a new fee-for-service physician payment incentivizing enhanced hospital discharge communication was not associated with significant changes in the risks of unplanned hospital readmission or mortality within 30 days. Policy introduction was associated with a substantial decrease in prescription fills for relatively contra-indicated medications in the elderly, but no improvement in prescription fills for beta-blockers after cardiovascular hospitalization. Our analyses suggest the introduction of the incentive payment policy did not result in significant changes in population risk of unplanned hospital readmission.

Several explanations of our findings are possible. First, the incentive payment might have remunerated physicians for established routines rather than incentivizing new behaviours. Second, physician behaviour might have remained unchanged because of suboptimal incentive design, potentially including insufficient monetary value, lack of immediacy between the incentive and the incentivized behaviour, framing of the incentive as an additional payment (rather than as a financial loss) and lack of verification that incentivized tasks were performed. Third, incentivized physician behaviours might be ineffective if readmission risks are predominantly influenced by factors beyond the control of hospital physicians. Only 27% of unplanned hospital readmissions are thought to be preventable through optimal medical care, suggesting inadequate access to primary care, insufficient community supports, limited health literacy, treatment non-adherence, socioeconomic inequalities and other forces contribute substantially to readmission risk.8,58,59,60,61,62,63,64 In contrast to the physician-focused G78717 incentive payment, successful readmission reduction initiatives have addressed these contributors using multi-component interventions and a broad coalition of community care providers spanning multiple disciplines and a range of regional health and social service organizations.65,66,67 These contrasts suggest physician-focused incentives alone might have a limited influence on readmission risks.

The G78717 policy was associated with a substantial decrease in prescription fills for relatively contra-indicated medications in the elderly, but no improvement in prescription fills for beta-blockers after cardiovascular hospitalization. This discrepancy might occur because human psychology dictates that medication reconciliation detects errors of commission (e.g. inappropriately prescribed medications) more effectively than errors of omission (e.g. indicated yet missing medications).12,68,69 However, the observed reduction in inappropriate prescriptions for the elderly might instead reflect trends in prescription of benzodiazepines and hypnotics (Item SA13). Other interventions including workflow redesign, targeted training, automated EHR alerts based on established diagnoses or new test results, and physician-specific performance data and feedback may better address shortcomings in evidence-based discharge medications.70

Our study has several limitations. First, physician uptake of the incentive payment was gradual and incomplete. The incentive payment policy may thus appear ineffective at the population level even if incentive payments were efficacious among patients receiving the incentivized services. Uptake might have been modest because provider awareness about the new fee code was limited, because the requirements of the code were perceived as burdensome or because the monetary value of the incentive was unappealing relative to other reimbursed services, but our data do not distinguish between these possibilities. Second, temporal confounding by other policy interventions and unrecognized secular trends may bias interrupted time-series analyses. A previous analysis found that the introduction of partial activity-based funding for BC hospitals in 2010 resulted in no change in the risk of readmission.71 In 2012, BC introduced a “Home First” policy to discourage entry to long-term care directly from an acute care hospital; the effect on unplanned hospital readmissions remains unknown.72 Third, we lacked granular clinical information and were unable to directly assess if the incentive payment policy resulted in more comprehensive discharge care plans, more thoughtful medication review or improved physician-to-physician communication at the time of hospital discharge. Fourth, our study focused on hospital readmissions, mortality, and markers of prescription quality and did not evaluate other potential goals of the incentive payment policy such as aligning remuneration with the work required to complete a high-quality hospital discharge or addressing the imbalance in financial compensation between procedural and cognitive medical specialties. Fifth, our study was set within a single Canadian province and may not be generalizable to settings with other physician payment models.

Among patients with non-elective hospital admissions of 5 days or longer, introduction of a physician payment to incentivize enhanced discharge planning was not associated with significant changes in the risks of subsequent unplanned readmission or death. Decision-makers seeking to reduce unplanned hospital readmissions should consider our findings before implementing similar physician incentive payments elsewhere.

References

All-cause readmission to acute care and return to the emergency department. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2012.

Your health system: All patients readmitted to hospital. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institutes of Health Information, 2010. (Accessed 22 Feb 2021 at https://yourhealthsystem.cihi.ca/hsp/indepth?lang=en#/)

Lum HD, Studenski SA, Degenholtz HB, Hardy SE. Early hospital readmission is a predictor of one-year mortality in community-dwelling older Medicare beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27(11):1467-74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2116-3.

Staples JA, Thiruchelvam D, Redelmeier DA. Site of hospital readmission and mortality: a population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open 2014;2:E77-85.

Lapointe-Shaw L, Mamdani M, Luo J, et al. Effectiveness of a financial incentive to physicians for timely follow-up after hospital discharge: A population-based time series analysis. CMAJ. 2017;189(39):e1224-e1229. doi: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170092.

Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2011 Apr 21;364(16):1582.

Health Quality Ontario. Effect of early follow-up after hospital discharge on outcomes in patients with heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2017;17(8):1-37.

Horwitz LI, Moriarty JP, Chen C, Fogerty RL, Brewster UC, Kanade S, Ziaeian B, Jenq GY, Krumholz HM. Quality of discharge practices and patient understanding at an academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1715-22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9318.

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-41.

Hoyer EH, Odonkor CA, Bhatia SN, Leung C, Deutschendorf A, Brotman DJ. Association between days to complete inpatient discharge summaries with all-payer hospital readmissions in Maryland. J Hosp Med 2016;11(6):393-400. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2556.

Callen J, Georgiou A, Li J, Westbrook JI. The safety implications of missed test results for hospitalised patients: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(2):194-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.044339.

Redmond P, McDowell R, Grimes TC, Boland F, McDonnell R, Hughes C, Fahey T. Unintended discontinuation of medication following hospitalisation: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e024747. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024747

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003;138(3):161-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007.

Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, Dupuis N, Chernish R, Chandok N, Khan A, van Walraven C. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345-9. Erratum in: CMAJ. 2004 Mar 2;170(5):771.

Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, Observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N Engl J Med 2016;374(16):1543-51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1513024.

Bindman AB, Cox DF. Changes in Health Care Costs and Mortality Associated With Transitional Care Management Services After a Discharge Among Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(9):1165-1171. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2572.

Lavergne MR, Law MR, Peterson S, Garrison S, Hurley J, Cheng L, McGrail K. A population-based analysis of incentive payments to primary care physicians for the care of patients with complex disease. CMAJ. 2016;188(15):E375-E383. doi: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.150858.

Lavergne MR, Law MR, Peterson S, Garrison S, Hurley J, Cheng L, McGrail K. Effect of incentive payments on chronic disease management and health services use in British Columbia, Canada: Interrupted time series analysis. Health Policy 2018;122(2):157-164. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.11.001.

Rudoler D, de Oliveira C, Cheng J, Kurdyak P. Payment incentives for community-based psychiatric care in Ontario, Canada, CMAJ. 2017;189(49):E1509-E1516. doi: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.160816.

Kiran T, Victor JC, Kopp A, Shah BR, Glazier RH. The relationship between financial incentives and quality of diabetes care in Ontario, Canada, Diabetes Care 2012;35(5):1038-46. doi: https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-1402.

Kiran T, Wilton AS, Moineddin R, Paszat L, Glazier RH. Effect of payment incentives on cancer screening in Ontario primary care. Ann Fam Med 2014;12(4):317-23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1664.

Li J, Hurley J, DeCicca P, Buckley G. Physician response to pay-for-performance: evidence from a natural experiment. Health Econ 2014;23(8):962-78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2971.

Specialist Services Committee of British Columbia [internet]. Vancouver (BC): Specialist Services Committee of British Columbia; c2010-2019. Discharge Care Plan for Complex Patients Fee (G78717); c2012. Accessed 29 July 2019 at http://sscbc.ca/fees/discharge-care-plan-complex-patients-fee

Canada Health Act, 1984, c. 6, s. 10.

Lavergne MR, Peterson S, McKendry R, Sivananthan S, McGrail K. Full-service family practice in British Columbia: policy interventions and trends in practice, 1991-2010. Healthc Policy 2014;9(4):32-47.

2019 Physician Master Agreement (2019). Article 8.2 "Core Mandate of the Joint Clinical Committees", subarcticle (a). Accessed 29 July 2019 from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/msp/negotiated-agreements-with-the-doctors-of-bc

Pencarrick Hertzman C, Meagher N, McGrail KM. Privacy by Design at Population Data BC: a case study describing the technical, administrative, and physical controls for privacy-sensitive secondary use of personal information for research in the public interest. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012:25–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001011.

Discharge Abstract Database: Canadian Institute for Health Information [creator] (2018): Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations). V2. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH (2018). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data

Mustard CA, Derksen S, Berthelot JM, Wolfson M. Assessing ecologic proxies for household income: A comparison of household and neighbourhood level income measures in the study of population health status. Health Place 1999;5(2):157–71.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43(11): 1130-1139.

Lix L, Yogendran M, Burchill C, Metge C, Mckeen N, Moore D, et al. Defining and validating chronic diseases: An administrative data approach. Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy; 2006.

PharmaNet: BC Ministry of Health [creator] (2018): PharmaNet. V2. BC Ministry of Health [publisher]. Data Extract. Data Stewardship Committee (2018). http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data

SAS Institute Inc. 2018. SAS/ETS® 15.1 User’s Guide. Cary: SAS Institute Inc.

Wauters M, Elseviers M, Vaes B, Degryse J, Dalleur O, Vander Stichele R, Christiaens T, Azermai M. Too many, too few, or too unsafe? Impact of inappropriate prescribing on mortality, and hospitalization in a cohort of community-dwelling oldest old. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016;82(5):1382-1392. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13055.

Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med 2011;365 (21):2002-2012.

Bradley EH, Herrin J, Mattera JA, Holmboe ES, Wang Y, Frederick P, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Quality improvement efforts and hospital performance: rates of beta-blocker prescription after acute myocardial infarction. Med Care 2005;43(3):282-92.

Stukel TA, Alter DA, Schull MJ, Ko DT, Li P. Association between hospital cardiac management and outcomes for acute myocardial infarction patients. Med Care 2010;48(2):157-65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd4da7.

Kramer JM, Curtis LH, Dupree CS, Pelter D, Hernandez A, Massing M, Anstrom KJ. Comparative effectiveness of beta-blockers in elderly patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2008;168(22):2422-8; discussion 2428-32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2008.511.

DiMartino LD, Shea AM, Hernandez AF, Curtis LH. Use of guideline-recommended therapies for heart failure in the Medicare population. Clin Cardiol 2010;33(7):400-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.20760.

Cox JL, Ramer SA, Lee DS, Humphries K, Pilote L, Svenson L, Tu JV; Canadian Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Team Investigators. Pharmacological treatment of congestive heart failure in Canada: a description of care in five provinces. Can J Cardiol 2005;21(4):337-43.

Ivers NM, Schwalm JD, Jackevicius CA, Guo H, Tu JV, Natarajan M. Length of initial prescription at hospital discharge and long-term medication adherence for elderly patients with coronary artery disease: a population-level study. Can J Cardiol 2013;29(11):1408-14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2013.04.009.

Banerjee D, Stafford RS. Lack of improvement in outpatient management of congestive heart failure in the United States. Arch Intern Med 2010;170(15):1399-400. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.270.

Mosalpuria K, Agarwal SK, Yaemsiri S, Pierre-Louis B, Saba S, Alvarez R, Russell SD. Outpatient management of heart failure in the United States, 2006-2008. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41(3):253-61. doi: https://doi.org/10.14503/THIJ-12-2947. eCollection 2014 Jun.

Masoudi FA, Ponirakis A, de Lemos JA, Jollis JG, Kremers M, Messenger JC, Moore JW, Moussa I, Oetgen WJ, Varosy PD, Vincent RN, Wei J, Curtis JP, Roe MT, Spertus JA. Trends in U.S. Cardiovascular Care: 2016 Report From 4 ACC National Cardiovascular Data Registries. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69(11):1427-1450. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.005.

Winkelmayer WC, Bucsics AE, Schautzer A, Wieninger P, Pogantsch M; Pharmacoeconomics Advisory Council of the Austrian Sickness Funds. Use of recommended medications after myocardial infarction in Austria. Eur J Epidemiol 2008;23(2):153-62.

Maio V, Marino M, Robeson M, Gagne JJ. Beta-blocker initiation and adherence after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2011;18(3):438-45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1741826710389401.

Deschaseaux C, McSharry M, Hudson E, Agrawal R, Turner SJ. Treatment Initiation Patterns, Modifications, and Medication Adherence Among Newly Diagnosed Heart Failure Patients: A Retrospective Claims Database Analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(5):561-71. doi: https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.5.561.

Johnson D, Jin Y, Quan H, Cujec B. Beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/receptor blockers prescriptions after hospital discharge for heart failure are associated with decreased mortality in Alberta, Canada, J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42(8):1438-45.

Diamant MJ, Virani SA, MacKenzie WJ, Ignaszewski A, Toma M, Hawkins NM. Medical therapy doses at hospital discharge in patients with existing and de novo heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2019. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.12454

American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13702.

Morgan SG, Hunt J, Rioux J, Proulx J, Weymann D, Tannenbaum C. Frequency and cost of potentially inappropriate prescribing for older adults: a cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open 2016;4(2):E346-51. doi: https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20150131. eCollection 2016 Apr-Jun.

Weymann D, Gladstone EJ, Smolina K, Morgan SG. Long-term sedative use among community-dwelling adults: a population-based analysis. CMAJ Open 2017;5(1):E52-E60. doi: https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20160056.

McKean M, Pillans P, Scott IA. A medication review and deprescribing method for hospitalised older patients receiving multiple medications. Intern Med J 2016;46(1):35-42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.12906.

Kanaan AO, Donovan JL, Duchin NP, Field TS, Tjia J, Cutrona SL, Gagne SJ, Garber L, Preusse P, Harrold LR, Gurwitz JH. Adverse drug events after hospital discharge in older adults: types, severity, and involvement of Beers Criteria Medications. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61(11):1894-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12504.

Hudhra K, García-Caballos M, Casado-Fernandez E, Jucja B, Shabani D, Bueno-Cavanillas A. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescriptions identified by Beers and STOPP criteria in co-morbid older patients at hospital discharge. J Eval Clin Pract 2016;22(2):189-93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12452.

Davidoff AJ, Miller GE, Sarpong EM, Yang E, Brandt N, Fick DM. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults using the 2012 Beers criteria. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63(3):486-500. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13320.

Canadian Institute of Health Information. Case mix [internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institute of Health Information; [updated 2019]. Accessed August 5, 2019 at https://www.cihi.ca/en/submit-data-and-view-standards/methodologies-and-decision-support-tools/case-mix).

Kangovi S, Grande D. Hospital readmissions--not just a measure of quality. JAMA. 2011;306(16):1796-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1562.

Herrin J, St Andre J, Kenward K, Joshi MS, Audet AM, Hines SC. Community factors and hospital readmission rates. Health Serv Res 2015;50(1):20-39.

van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, Austin PC, Forster AJ. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review. CMAJ 2011;183(7):E391-E402.

van Walraven C, Jennings A, Taljaard M, et al. Incidence of potentially avoidable urgent readmissions and their relation to all-cause urgent readmissions. CMAJ 2011;183(14): E1067-E1072.

Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, Sehgal N, Lindenauer PK, Metlay JP, Fletcher G, Ruhnke GW, Flanders SA, Kim C, Williams MV, Thomas L, Giang V, Herzig SJ, Patel K, Boscardin WJ, Robinson EJ, Schnipper JL. Preventability and causes of readmissions in a national cohort of general medicine patients. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(4):484-93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7863.

Jencks SF, Brock JE. Hospital accountability and population health: lessons from measuring readmission rates. Ann Intern Med 2013;159(9):629-30. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00010.

Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, Bueno H, Ross JS, Horwitz LI, Barreto-Filho JA, Kim N, Bernheim SM, Suter LG, Drye EE, Krumholz HM. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.216476

Brock J, Mitchell J, Irby K, Stevens B, Archibald T, Goroski A, Lynn J; Care Transitions Project Team. Association between quality improvement for care transitions in communities and rehospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2013;309(4):381-91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.216607

Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, Brito JP, Mair FS, Gallacher K, Wang Z, Erwin PJ, Sylvester T, Boehmer K, Ting HH, Murad MH, Shippee ND, Montori VM. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174(7):1095-107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1608.

Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155(8):520–528.

Uhlenhopp DJ, Aguilar O, Dai D, Ghosh A, Shaw M, Mitra C. Hospital-Wide Medication Reconciliation Program: Error Identification, Cost-Effectiveness, and Detecting High-Risk Individuals on Admission. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2020;9:195-203. doi: https://doi.org/10.2147/IPRP.S269857.

Karaoui LR, Chamoun N, Fakhir J, Abi Ghanem W, Droubi S, Diab Marzouk AR, Droubi N, Masri H, Ramia E. Impact of pharmacy-led medication reconciliation on admission to internal medicine service: experience in two tertiary care teaching hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):493. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4323-7.

Rungvivatjarus T, Kuelbs CL, Miller L, Perham J, Sanderson K, Billman G, Rhee KE, Fisher ES. Medication Reconciliation Improvement Utilizing Process Redesign and Clinical Decision Support. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2020;46(1):27-36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.09.001.

Sutherland JM, Liu G, Crump RT, Law M. Paying for volume: British Columbia’s experiment with funding hospitals based on activity. Health Policy. 120: 1322–1328. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.09.010.

B.C. continues to expand primary and community care. News release, Government of British Columbia. Victoria (BC). March 1, 2013. Accessed 24 June 2019 at https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2013HLTH0036-000376

Acknowledgements

We thank Penny Tam and Laura Anderson for insightful comments on early drafts of this article.

Funding

This article was supported by grants from the Specialist Services Committee (a collaboration between Doctors of BC and the BC Ministry of Health), the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JAS, JMS and GL were responsible for study concept and design. JAS was responsible for the acquisition of the data and drafting of the manuscript. GL had full access to all study data and was responsible for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors were responsible for the critical revision of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

JAS has received clinical income from the incentive payment. As a co-funder of this work, the Specialist Services Committee might be perceived as having a political or financial interest in demonstrating the effectiveness of the fee code. As recipients of operational support from SSC for this project, Drs Staples and Sutherland might be perceived as incentivized to produce findings that lend support to claims of the effectiveness of the fee code.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Staples, J.A., Liu, G., Brubacher, J.R. et al. Physician Financial Incentives to Reduce Unplanned Hospital Readmissions: an Interrupted Time Series Analysis. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 3431–3440 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06803-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06803-8