Abstract

Background

Concern regarding pelvic examinations may be more common among women experiencing intimate partner violence.

Objective

We examined women’s attitudes towards pelvic examination with history of intimate partner violence (pressured to have sex, or verbal, or physical abuse).

Design

Secondary analysis of data from a cluster randomized trial on contraceptive access.

Participants

Women aged 18–25 were recruited at 40 reproductive health centers across the USA (2011–2013).

Main Measures

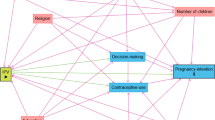

Delays in clinic visits for contraception and preference to avoid pelvic examinations, by history of ever experiencing pressured sex, verbal, or physical abuse from a sexual partner, reported by frequency (never, rarely, sometimes, often). We used multivariable logistic regression with generalized estimating equations for clustered data.

Key Results

A total of 1490 women were included. Ever experiencing pressured sex was reported by 32.4% of participants, with 16.5% reporting it rarely, 12.1% reporting it sometimes, and 3.8% reporting it often. Ever experiencing verbal abuse was reported by 19.4% and physical abuse by 10.2% of participants. Overall, 13.2% of participants reported ever having delayed going to the clinic for contraception to avoid having a pelvic examination, and 38.2% reported a preference to avoid pelvic examinations. In multivariable analysis, women reporting that they experienced pressured sex often had significantly higher odds of delaying a clinic visit for birth control (aOR 3.10 95% CI 1.39–6.84) and for reporting a preference to avoid pelvic examinations (aOR 2.91 95% CI 1.57–5.40). We found no associations between delay of clinic visits or preferences to avoid a pelvic examination and verbal or physical abuse.

Conclusions

History of pressured sex from an intimate partner is common. Among women who have experienced pressured sex, concern regarding pelvic examinations is a potential barrier to contraception. Communicating that routine pelvic examinations are no longer recommended by professional societies could potentially reduce barriers and increase preventive healthcare visits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Pelvic examinations were once required to obtain hormonal contraception and posed a substantial barrier.1 Reducing barriers to contraceptive access is critical to optimizing person-centered reproductive healthcare.2 In efforts to reduce barriers to contraceptive care, the World Health Organization in 1994 stated that combined hormonal oral contraception can be safely prescribed without a pelvic examination.1 Organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other professional medical organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in 1996 and the American College of Physicians (ACP), have echoed this sentiment and expanded it to other hormonal forms including injectable and implantable methods.2,3,4,5 Despite these recommendations, many providers still require a pelvic examination prior to prescribing or administering contraception, creating an unnecessary barrier to access contraception, especially in vulnerable populations.6,7

Intimate partner violence (IPV) affects millions of people in the United States (U.S.) and is a preventable and serious public health problem. IPV is defined by the CDC as abuse or aggression that occurs in close relationships and can include physical, sexual, or verbal abuse. Over forty-three million U.S. women have experienced some form of IPV in their lifetime, and approximately twenty-two million U.S. women report some form of sexual violence from an intimate partner in their lifetime. Of these women experiencing some form of IPV, 71.1% report first experiencing IPV before the age of 25.8 Women who have experienced IPV report lower rates of contraceptive use, use of less effective methods, and less consistent use than those without an IPV history.9,10 Many studies have investigated the possible factors responsible for these patterns, but have primarily focused on reasons related to the IPV such as fear of violence from their partner, challenges hiding contraception from their partner, or fear of contraceptive sabotage from their partner.11,12,13

Women who have experienced IPV may be especially concerned about pelvic examinations. Previous research has found that these examinations can re-traumatize women, and other studies have found that women with history of IPV experience more pain and discomfort with the examination.14,15,16 Thus, a patient’s desire to avoid pelvic examinations may represent an important barrier to seeking contraceptive care among women with history of IPV due to traumatic experiences. This analysis aims to investigate attitudes towards pelvic examinations among women with a history of intimate partner related pressure to have sex (pressured sex), verbal or physical abuse receiving reproductive healthcare services. We hypothesized that concern regarding pelvic examinations would be more prevalent among women who have experienced intimate partner violence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This secondary data analysis uses baseline questionnaire data collected during a cluster randomized trial to increase contraceptive access in 40 family planning and abortion clinics across the United States.17 In the trial, 20 health centers were randomly assigned to receive a provider training in evidence-based contraceptive care including intrauterine device (IUD) and implant placement; providers at the other 20 sites acted as controls with usual standard practice. Fifteen hundred women aged 18–25 were enrolled in the study and were followed for one year. Patients receiving either family planning or abortion care were recruited if they were receiving contraceptive counseling and not desiring pregnancy in the next 12 months. Data were collected between 2011 and 2013. The study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board and the Allendale Investigational Review Board, Old Lyme, CT.

Measurements

The study outcome was whether the participant had ever delayed a clinic visit for contraception to avoid a pelvic examination, as evaluated with the following question: “In the past, I have put off going to the clinic for birth control because I did not want to have a pelvic examination” (yes/no). We also investigated an additional survey item to understand preferences towards pelvic examinations: “Unless I have symptoms of something wrong, I would rather not have a pelvic examination when I visit a clinic for birth control” (yes/no). Of note, in the survey, the term “pelvic examination” was not defined for participants. The independent variables of interest were history of pressure to have sex, verbal abuse, or physical abuse, reported by frequency (never, rarely, sometimes, often). These survey items were based on prior studies investigating IPV in diverse populations.18,19,20,21 Furthermore, these survey questions investigating different forms of IPV were asked together and were in reference to previous sexual partners. Pressured sex was measured with the question “How often has a sexual partner ever pressured you to have sex?” Verbal abuse was measured with the question “how often has a sexual partner threatened to leave you, called you names, or sworn at you?”. Physical abuse was measured with the question “How often has a sexual partner ever beaten you up, thrown something at you, or hit, pushed, slapped, kicked, or choked you?”

We assessed an interaction with age and abuse types. For purposes of interaction analyses, abuse types were dichotomized to yes (“rarely,” “sometimes,” “often”)/no. Age was dichotomized to 17–20 years of age and those 21 years of age and older for our interaction analyses because women 21 and older should be undergoing routine cervical cancer screening and will have likely experienced a pelvic examination as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) began recommending screening beginning at age 21 in its 2012 recommendations.

Analysis

The analysis population included all participants responding to the study outcome variables for delay of clinic visits due to concern regarding pelvic examination (n = 1490) and preference to avoid pelvic examination (n = 1486). We used Pearson’s chi-squared testing in bivariate analyses, and then multivariable generalized estimating equations for clustered data, with a logit link, to examine the associations of each abuse variable with the outcome variables, delaying a clinic visit to avoid an examination and pelvic examination preferences. Multivariable analyses regarding delayed clinical visits due to pelvic examinations and pelvic examination preferences included all abuse types and the following covariates: age, race/ethnicity, nulliparity, health insurance, and practice setting, which were selected a priori as possible confounders, and trial arm to account for the study design. We also estimated a model to investigate the potential for statistical interaction between age and abuse types and effect on delay of clinical visits.

All analyses were performed with STATA 16, and we considered differences at the p < 0.05 level as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Of the 1490 participants in the study, the mean age was 21.5 (SD 2.2 years). Half (49.6%) self-identified as White, 27.2% as Latina/Hispanic, 14.8% as Black, and 8.4% as Asian/other. Eighty percent had completed high school. Only 6.1% were currently married. 27.3% of the participants had Medicaid/state insurance, 29.8% had private insurance, 38.0% did not have any form of insurance, and 4.9% did not know if they had insurance. 70.7% of participants were nulliparous. Fifty-seven percent of the participants were seen in a family planning clinic while the rest were seen in an abortion clinic. Finally, 53.5% of the participants were in the intervention arm of the original cluster randomized trial (Table 1).

Almost one-third (32.4%) reported ever experiencing pressure from a sexual partner to have sex. Overall, 16.5% reported they had experienced pressured sex rarely, 12.1% reported it sometimes, and 3.8% reported it often. About 20% responded ever experiencing a sexual partner threaten to leave them, called them names, or sworn at them. 9.0% reported experiencing it rarely, 7.1% reported sometimes, and 3.3% reported often. 10.2% reported ever experiencing physical abuse from a sexual partner. 5.4% reporting rarely experiencing physical abuse, 3.6% reporting experiencing sometimes, and 1.2% reporting experiencing physical abuse often.

Relationship Between Intimate Partner Violence and Delaying Clinic Visits to Avoid Pelvic Examination

Overall, 13.2% (n = 196) of the sample reported that they had delayed a clinic visit to avoid having a pelvic examination. In bivariable analyses, of the types of abuse we examined, only pressured sex was significantly associated with ever delaying a clinic visit to avoid pelvic examination (p < 0.001). Verbal abuse and physical abuse were not associated with clinic delays (p = 0.39; p = 0.29, respectively) (Table 2).

In adjusted models, the odds of delaying going to clinic to avoid a pelvic examination was 76% higher among women reporting pressured sex rarely (aOR 1.76 95% CI 1.31–2.37), compared to participants who had never experienced pressured sex. Odds were 210% higher among women reporting pressured sex often (aOR 3.10 95% CI 1.39–6.93), and odds were elevated for those reporting pressured sex sometimes (aOR 1.53 95% CI 0.96–2.43), though shy of significance. No significant statistically associations were found for verbal abuse or physical abuse. Nulliparous women were found to have higher odds of delaying clinic visits compared to parous women (aOR 1.60 95% CI 1.04–2.44). Finally, African American and Latina/Hispanic participants were less likely to delay a pelvic examination in comparison to white participants (aOR 0.46 95% CI 0.32–0.66 and aOR 0.49 95% CI 0.38–0.64, respectively) (Table 3).

In addition, we found no evidence of interaction between abuse forms and age (not shown).

Preferences for Pelvic Examination During Contraceptive Visits

Overall, 38.2% (n = 568) of the participants reported that they would not want to have a pelvic examination during clinical visits for contraception. In bivariable analyses, of the types of abuse we examined, only pressured sex was significantly associated with participants preferring not to have a pelvic examination (p = 0.002). Verbal abuse and physical abuse were not associated with preferences for not having a pelvic examination (p = 0.92; p = 0.56, respectively).

In models evaluating preferences for not having a pelvic examination during clinic visits for contraception, we found 63% higher odds of not wanting an examination among women reporting pressured sex sometimes (aOR 1.63 95% CI 1.11–2.38) and 191% higher odds among women reporting pressured sex often (aOR 2.85 95% CI 1.58–5.40) as compared to women that have never experienced pressured sex (Supplemental Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Principal Findings

In this study, approximately a third of the young women reported ever experiencing sexual coercion or pressure to have sex against their will which is higher than reported national prevalences.8 These women that experienced pressure to have sex were more likely to report having delayed clinical visits for contraception to avoid a pelvic examination and were more likely to not want a pelvic examination when visiting a clinic for contraception. Prior research has shown that fear of pelvic examinations may lead younger women to delay or avoid obtaining oral contraception, and our findings indicate that this effect is even more dramatic in women with history of pressured sex.22 Furthermore, our results are aligned with other research regarding history of sexual abuse and the pelvic exam which has found that women with a history of sexual violence are more likely to find the pelvic examination distressing, embarrassing, or frightening, and are more likely to experience more pain during the actual exam.14,15 Previous research has shown that women who have experienced IPV are more likely to delay clinical visits in general.23 Our research provides potential insight into one reason women with IPV may delay clinical visits: a preference for avoiding a pelvic examination.

Clinical Implications

Our findings are important in context, as they suggest that young women experiencing IPV, who may already have limited access to contraception or use contraception inconsistently, also face barriers to care from healthcare providers and healthcare system.9,10 Despite recommendations that many contraception types do not require pelvic exams, providers who require a pelvic examination before providing contraception create a barrier for vulnerable women who have experienced pressured sex. These healthcare barriers could potentially stand in the way of pregnancy prevention and increase overall health risks for patients.6,24 These results further support the importance of removing requirements for pelvic examination for contraceptive access in all healthcare settings. Healthcare providers and systems may need to be evaluated on this practice as a key quality indicator.

In addition to an absence of clinical justification for pelvic examinations to determine medical eligibility for contraception, the importance of this examination for routine preventive screening to prevent disease is also questionable. Currently, the ACP and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommend against performing pelvic examinations in asymptomatic, non-pregnant women.4,25 The USPSTF states there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation regarding routine pelvic examinations.26 Finally, ACOG believes routine pelvic examinations should be performed when indicated by medical history and symptoms, but can also be a shared decision between providers and patients.27 Despite these guidelines, many physicians continue to perform unnecessary pelvic examinations, especially in younger populations.7,28,29 Many young women with history of IPV may be avoiding preventive clinic visits because they are worried that the visit may include a pelvic examination. This could be one potential reason for the decline in adequate cervical cancer screening over the past two decades.30 Communicating to women ages 30 and older with a history of IPV that cervical cancer screening can be done every 5 years with either cytology and high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) testing (co-testing) or hrHPV testing alone could potentially increase preventative visits and adequate cervical cancer screening.

Our study did not find any relationship between histories of physical or verbal abuse and delay of clinic visits for contraception, which is in line with previous findings that women with history of physical abuse and verbal abuse are not any more or less likely to seek preventative healthcare services.31,32,33

Limitations and Implications for Research

Our study had limitations. A pelvic exam, as defined by ACOG, can include visualization, insertion of the speculum, bimanual exam, and/or rectovaginal inspection.27 The questions used in this study did not specifically define the components of a pelvic exam. Thus, exactly what specific aspect of the pelvic examination might cause women to delay clinical visits is not known, or whether it is a more general reaction. Further research could investigate whether specific aspects of the pelvic exam are most uncomfortable for women. Second, our questionnaire only probed questions directly related to previous sexual partners, and did not elicit childhood physical, sexual, or verbal abuse, which may have a different effect on patient’s views on pelvic examinations. Further studies could work to better understand the effects of childhood trauma. Third, this study included participants who were already present at a healthcare facility where they received either family planning or abortion care services. These study participants had already overcome their concerns and come to clinic, so our results are not generalizable to women who do not make it to clinic. Our study likely underestimates the effects of pressured sex and concerns about pelvic examination. Also, while pressured sex was investigated in a series of questions related to IPV, there is the possibility for interpretation of the question to reflect normal responsive/reactive sexual desire among those in long-term relationships. Future studies should investigate other domains of sexual abuse and the effects on attitudes towards pelvic examinations. Additionally, the questionnaire collected cross-sectional data, so we are unable to establish temporality. Finally, this was not a pre-specified secondary data analysis of a cluster randomized trial; thus, a type I error is possible, though our p values for our significant findings are p value 0.005 to < 0.001 which is well under an adjusted p value for multiple comparisons.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our analysis found that pressured sex is very common and that the pelvic examinations are a specific healthcare-related barrier to care in patients with history of IPV that could serve as a barrier to contraception and other reproductive healthcare. Despite professional recommendations, many healthcare providers continue to perform unnecessary pelvic examinations which contributes to an assumption by patients that a pelvic exam is necessary to obtain effective contraception or other needed reproductive healthcare services.29 Communicating to the public and providers that routine pelvic examinations are no longer recommended by professional societies for contraception or routine preventive healthcare visits could potentially remove barriers and increase preventive healthcare visits for these women.

References

Stewart FH, Harper CC, Ellertson CE, Grimes DA, Sawaya GF, Trussell J. Clinical Breast and Pelvic Examination Requirements for Hormonal Contraception. JAMA. 2001;285(17):2232.

Committee opinion no. 615: Access to contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):250-255.

Committee opinion No. 534: well-woman visit. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(2 Pt 1):421-424.

Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Harris R, Starkey M, Denberg TD. Screening Pelvic Examination in Adult Women: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(1):67.

Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(4):1-66.

Henderson JT, Sawaya GF, Blum M, Stratton L, Harper CC. Pelvic Examinations and Access to Oral Hormonal Contraception. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116(6):1257-1264.

Yu JM, Henderson JT, Harper CC, Sawaya GF. Obstetrician-gynecologists’ beliefs on the importance of pelvic examinations in assessing hormonal contraception eligibility. Contraception. 2014;90(6):612-614.

Smith SG, Zhang X, Basile, KC, Merrick MT, Wang J, Kresnow M, Chen. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey:2015 Data Brief – Updated Release. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018.

Allsworth JE, Secura GM, Zhao Q, Madden T, Peipert JF. The Impact of Emotional, Physical, and Sexual Abuse on Contraceptive Method Selection and Discontinuation. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1857-1864.

Maxwell L, Devries K, Zionts D, Alhusen JL, Campbell J. Estimating the Effect of Intimate Partner Violence on Women’s Use of Contraception: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0118234.

Kusunoki Y, Barber JS, Gatny HH, Melendez R. Physical Intimate Partner Violence and Contraceptive Behaviors Among Young Women. J Women's Health. 2018;27(8):1016-1025.

Moore AM, Frohwirth L, Miller E. Male reproductive control of women who have experienced intimate partner violence in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(11):1737-1744.

Swan H, O’Connell DJ. The Impact of Intimate Partner Violence on Women’s Condom Negotiation Efficacy. J Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(4):775-792.

Weitlauf JC, Finney JW, Ruzek JI, et al. Distress and pain during pelvic examinations: effect of sexual violence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1343-1350.

Weitlauf JC, Frayne SM, Finney JW, et al. Sexual Violence, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and the Pelvic Examination: How Do Beliefs About the Safety, Necessity, and Utility of the Examination Influence Patient Experiences? J Women's Health. 2010;19(7):1271-1280.

Watson V. Re-Traumatization of Sexual Trauma in Women’s Reproductive Health Care [Honors Thesis Project], University of Tennesee. 2016.

Harper CC, Rocca CH, Thompson KM, et al. Reductions in pregnancy rates in the USA with long-acting reversible contraception: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9993):562-568.

Raiford JL, Diclemente RJ, Wingood GM. Effects of Fear of Abuse and Possible STI Acquisition on the Sexual Behavior of Young African American Women. 2009;99(6):1067-1071.

Seth P, Wingood GM, Robinson LS, Raiford JL, Diclemente RJ. Abuse Impedes Prevention: The Intersection of Intimate Partner Violence and HIV/STI Risk Among Young African American Women. 2015;19(8):1438-1445.

Drew LB, Mittal M, Thoma ME, Harper CC, Steinberg JR. Intimate Partner Violence and Effectiveness Level of Contraceptive Selection Post-Abortion. J Women's Health. 2019.

Feltner C, Wallace I, Berkman N, et al. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews. In: Screening for Intimate Partner Violence, Elder Abuse, and Abuse of Vulnerable Adults: An Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). 2018.

Westhoff CL, Jones HE, Guiahi M. Do New Guidelines and Technology Make the Routine Pelvic Examination Obsolete?. 2011;20(1):5-10.

Miller E, Decker MR, Raj A, Reed E, Marable D, Silverman JG. Intimate Partner Violence and Health Care-Seeking Patterns Among Female Users of Urban Adolescent Clinics. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(6):910-917.

Harper C, Balistreri E, Boggess J, Leon K, Darney P. Provision of hormonal contraceptives without a mandatory pelvic examination: the first stop demonstration project. Fam Plan Perspect. 2001;33(1):13-18.

AAFP Recommends Against Pelvic Exams in Asymptomatic Women https://www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20170425aafppelvicexam.html. Published 2017. Updated April 25. Accessed Apr 2020.

Guirguis-Blake JM, Henderson JT, Perdue LA. Periodic Screening Pelvic Examination. 2017;317(9):954.

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 754: The Utility of and Indications for Routine Pelvic Examination. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132(4):e174-e180.

Henderson JT, Harper CC, Gutin S, Saraiya M, Chapman J, Sawaya GF. Routine bimanual pelvic examinations: practices and beliefs of US obstetrician-gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(2):109.e101-109.e107.

Qin J, Saraiya M, Martinez G, Sawaya GF. Prevalence of Potentially Unnecessary Bimanual Pelvic Examinations and Papanicolaou Tests Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women Aged 15-20 Years in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(2):274.

Watson M, Benard V, King J, Crawford A, Saraiya M. National assessment of HPV and Pap tests: Changes in cervical cancer screening, National Health Interview Survey. Prev Med. 2017;100:243-247.

Hegarty KL, O’Doherty LJ, Chondros P, et al. Effect of Type and Severity of Intimate Partner Violence on Women’s Health and Service Use. J Interpersonal Violence 2013;28(2):273-294.

Macy RJ, Ferron J, Crosby C. Partner Violence and Survivors’ Chronic Health Problems: Informing Social Work Practice. 2009;54(1):29-43.

Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Rivara FP, Thompson RS. Health Care Utilization and Costs Associated with Physical and Nonphysical-Only Intimate Partner Violence. Health Serv Res 2009;44(3):1052-1067.

Acknowledgments

We thank Planned Parenthood investigators and research coordinators.

Funding

This study was funded by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation (#2010-5442).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board and the Allendale Investigational Review Board, Old Lyme, CT.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 31 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Holt, H.K., Sawaya, G.F., El Ayadi, A.M. et al. Delayed Visits for Contraception Due to Concerns Regarding Pelvic Examination Among Women with History of Intimate Partner Violence. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 1883–1889 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06334-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06334-8