Abstract

Background

Past research has examined the health outcomes of early sexual trauma in reproductive age women, but little is known about potential long-term effects in older age.

Objective

To examine associations between early life sexual trauma and later life sexual/genitourinary dysfunction and general functional disability in women.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of nationally representative observational data from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (2010–2011)

Participants

One thousand seven hundred forty-five US women aged ≥ 50 years

Main Measures

Two forms of early life sexual trauma (childhood sexual abuse and unwanted first sexual experience), sexual/genitourinary dysfunction (pain during sex, lack of pleasure during sex, urinary incontinence, other urinary symptoms), and general functional disability (difficulty performing 7 activities of daily living (ADLs) or 8 instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)), assessed by interview and questionnaire.

Key Results

Of 1745 women, 11% reported a history of childhood sexual abuse and 39% an unwanted first sexual experience. Childhood sexual abuse was associated with later life sexual/genitourinary dysfunction (pain during sex [OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.1–3.3], other urinary problems [OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2–3.1]), and difficulty with multiple ADLs/IADLs (walking across the room [OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2–3.1], getting in or out of bed [OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.2–3.3], bathing [OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.2–3.5], prepping meals [OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.5–3.8], shopping for food [OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.0–2.4], and completing light work [OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.0–2.4]), after adjusting for age, race, and education. Unwanted first sexual experience was associated with later life lack of pleasure with sex (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.1–2.5) and difficulty with ADLs/IADLs (walking one block [OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1–2.1], completing light work [OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1–2.1]) in adjusted analyses.

Conclusions

Early sexual trauma may be an under-recognized marker of risk of aging-related functional decline in women. Findings underline the importance of providing trauma-informed care for women across the aging spectrum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

An estimated one in five US women has been raped during their lifetime, and at least two in five report being subjected to other forms of sexual violence.1 Recent social movements such as #MeToo and #TimesUp have led to increased public awareness of sexual trauma experienced by women, highlighting problematic experiences that have not historically been discussed. In turn, this increased awareness has prompted more widespread investigation into the effects of sexual trauma or abuse on women’s health and well-being.2, 3

Women typically experience sexual trauma early in life, with the US Department of Justice reporting that a woman is most at risk of sexual assault at age 14.4 Since childhood and adolescence are psychologically and physically vulnerable times, early life sexual trauma or abuse may have uniquely powerful consequences on health. Past studies suggest that women who are victims of early sexual trauma may have more sexual and genitourinary problems or other general health conditions in their reproductive or midlife years.2, 5,6,7 They may also be more prone to revictimization later in life, including in older age.8 However, research on potential long-term consequences in older age is limited,9, 10 with prior studies focusing on specialized or referral populations or on mental health outcomes only.10,11,12 As such, little is known about potential associations between these early life exposures and a broader array of aging-related health outcomes, especially in more generalizable populations.

To address this gap, we examined the prevalence of two types of potentially traumatic early sexual experiences—childhood sexual abuse and an unwanted first sexual experience—and investigated associations with several forms of aging-related functional decline in a national sample of older women. To get a better sense of overlap of traumatic exposures between early life and later life, we also pursued an exploratory analysis examining associations between exposure to early sexual trauma and emotional abuse in older age. We aimed to provide new evidence to guide surveillance and care of aging women who have experienced early sexual trauma, as well as advance a broader perspective of sexual trauma that incorporates the entire lifespan.

METHODS

Study Population

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from the second wave of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP), an observational cohort designed to investigate relationships between biological, social, and psychological factors and health outcomes in older community-dwelling US adults.13 Details about the sampling process and study design for NSHAP have been described elsewhere.14 Briefly, the first wave of NSHAP used multistage area probability sampling to assemble a nationally representative sample of US adults aged 57–85, oversampling in areas with higher densities of Latino and African American individuals. Wave 2 consisted of re-interviews with Wave 1 respondents 5 years later, individuals who had been eligible for Wave 1 but had not responded previously, and cohabiting partners or spouses.

For Wave 2, trained interviewers conducted study visits in participants’ homes between August 2010 and May 2011 to pose questions surrounding sexual and social health, including sexual trauma. For sensitive questions, participants could opt to answer privately on a laptop or sealed questionnaire.15 For this investigation, we restricted our analytic sample to women at least 50 years of age who provided data about exposure to at least one form of early sexual trauma in NSHAP Wave 2. All participants provided informed consent before data collection, and all procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Chicago and the National Opinion Research Center.

Early Life Sexual Trauma Exposure Assessment

Early sexual trauma exposure was evaluated using structured, interviewer-administered questionnaire measures adapted from other large-scale studies.16,17,18,19 Childhood sexual abuse was assessed with a question from the National Health and Social Life Survey (1992): “Before you were 12 or 13 years old, did anyone touch you sexually?”; women responding yes were considered to have been exposed to childhood sexual abuse. Unwanted first sexual experience was assessed by asking women when they first had penetrative sexual intercourse with another person, followed by, “At this first occasion [of sex], is this something you wanted at the time, went along with, or were forced into?”; for this study, participants were considered to have had an unwanted first sexual experience if they “were forced into” or “went along with” that sexual experience as opposed to wanting it.

Sexual/Genitourinary Dysfunction Measures

Sexual problems in the past 12 months were assessed using interviewer-administered questionnaire measures adapted from the National Health and Social Life Survey20, including trouble lubricating, not finding sex pleasurable, and experiencing physical pain during intercourse. Urinary symptoms were evaluated using structured questions adapted from other epidemiological studies of older women.21, 22 Urinary incontinence was assessed by asking, “In the past 12 months, have you had difficulty controlling your bladder, including leaking small amounts of urine, leaking when you cough or sneeze, or not being able to make it to the bathroom on time?” Other urinary symptoms were assessed by asking, “In the past 12 months, have you had other problems with urinating, such as incomplete emptying, a weak urinary stream, straining to begin urination, or difficulty in postponing urination?” If participants answered affirmatively to either question, they were asked to characterize how frequently symptoms occurred. Our analysis focused on urinary symptoms occurring at least a few times a month, consistent with previous NSHAP studies.23,24,25

Functional Disability Measures

Functional disability was assessed using standardized questions assessing difficulty with completing each of seven activities of daily living (ADLs) (walking across room, walking one block, dressing, bathing or showering, eating, getting in or out of bed, and using the toilet) and eight instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (preparing meals, taking medications, managing money, shopping for groceries, performing light housework, using a telephone, driving the car during the day, and driving the car during the night). Answers were obtained using a 4-point Likert scale (“no difficulty,” “some difficulty,” “much difficulty,” and “unable to do”). For this analysis, participants were considered to have meaningful difficulty if they reported at least “some difficulty” with the activity.

Emotional Abuse in Older Age

To evaluate for an overlap of traumatic exposures between early life and later life, current exposure to elder emotional abuse was assessed via a leave-behind questionnaire using two structured questions similar to items from validated screening tools for elder mistreatment.26 This allowed participants to disclose information privately, rather than in the vicinity of other household members during in-person interviews conducted in participant homes. Participants were asked how often they felt “threatened or frightened” by (1) their partner or (2) another family member or one of their friends, with response options including “often,” “some of the time,” “hardly ever or rarely,” or “never.” For this analysis, women were considered to be at risk of emotional abuse if they gave any response other than “never.” The NSHAP Wave 2 survey did not collect data on other lifetime experiences of sexual trauma.

Other Sociodemographic and Clinical Covariates

Additional interviewer-assessed characteristics to describe the cohort included age, self-identified race/ethnicity, education, marital status, earned annual household income (not including interest or dividends), current alcohol consumption, current cigarette consumption, sexual activity, and self-reported physical and mental health. Body mass index was calculated from weight and height measured during study visits. Parity was assessed via leave-behind questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

Demographics and other characteristics of the sample were examined using weighted descriptive statistics. Subsequently, we developed multivariable logistic regression models to examine the odds of each type of sexual/genitourinary dysfunction predicted by each form of early sexual trauma. We also developed parallel models examining the odds of experiencing difficulty with each ADL and IADL associated with each form of early sexual trauma. All models were adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and education as demographic covariates that might confound associations between early sexual trauma and later life functional decline.27, 28 In our main models, we did not adjust for later life health factors such as obesity, comorbidity, or health status that could represent downstream effects of early sexual trauma and directly mediate its effects on later life functional decline. However, in supplementary analyses, we additionally adjusted for obesity due to its known associations with both sexual trauma and later life functional impairment.29,30,31 We also created supplementary models examining associations between early sexual trauma and self-reported overall physical and mental health in older age. Finally, we developed regression models examining associations between early sexual trauma and current elder emotional abuse, again adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, and education.

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) using survey procedures (e.g., surveymeans, surveyfreq, and surveylogistic). Sampling weights were used to ensure correct calculation of the point estimates. As recommended by NSHAP, we used weight accounting for non-response by age and race.15, 32,33,34 Stratification and clustering statements were used to calculate standard errors and the corresponding tests of statistical significance.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Of 2212 women in the second NSHAP wave, 368 were excluded from our analyses for age less than 50 years, and another 81 were excluded for not having completed at least one question about exposure to early sexual trauma. In the remaining 1745 women, the mean age was 71.1 ± 0.3 years, and the majority were white (81%), married (56%), and college educated (58%). Over half had an annual household income level ≤ $24,999 (51%). The majority were overweight or obese (72%) and multiparous (82%). Current alcohol use was reported by 51% of women, while only 12% reported smoking tobacco. Two fifths (43%) of women self-reported very good or excellent physical health (Table 1).

Eleven percent of women reported exposure to childhood sexual abuse, and 39% reported an unwanted first sexual experience (Table 2). No substantial differences in these exposures were detected across age groups. The average age of women at the time of an unwanted first sexual encounter was 18.0 (± 0.2) years, compared to 20.0 (± 0.2) years for women who had a wanted first sexual encounter (p < 0.01).

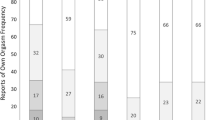

Of 1745 women, 158 (10%) experienced pain during sex, 348 (26%) had trouble lubricating, and 244 (17%) did not find sex pleasurable. In addition, 661 (41%) reported urinary incontinence, and 280 (17%) reported other urinary symptoms at least a few times a month. Further, 635 (35%) of women reported difficulty with at least one type of ADL and 996 (54%) reported difficulty with at least one type of IADL.

Associations Between Early Life Sexual Trauma Exposures and Later Life Functional Outcomes

In models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and education, women with a history of childhood sexual abuse had increased odds of reporting pain during sexual intercourse (OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.12–3.27) as well as other urinary problems (OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.17–3.10). Women with a history of unwanted first sexual experience had increased odds of reporting lack of pleasure during intercourse (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.13–2.45). No significant associations were seen between these exposures and other measures of sexual/genitourinary dysfunction (Table 3).

In multivariate analyses, women who experienced childhood sexual abuse had increased odds of experiencing difficulty with ADLs like walking across the room (OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.22–3.10), getting in or out of bed (OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.24–3.27), and bathing (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.15–3.53). In addition, women with a history of childhood sexual abuse had increased odds of reporting difficulty with IADLs such as prepping meals (OR 2.36, 95% CI 1.47–3.79), shopping for food (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.04–2.40), and completing light work (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.01–2.42). Women with a history of an unwanted first sexual experience had increased odds of reporting difficulty with walking one block (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.07–2.09) and completing light work (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.13–2.12), but no other ADLs or IADLs, in adjusted analyses (Table 4).

After additional adjustment for obesity, most associations between sexual trauma exposures and functional outcomes remained significant, suggesting they were independent of obesity (Appendix Tables 1 and 2).

In supplementary analyses, women with a history of childhood sexual abuse had increased odds of reporting fair/poor mental health, but not physical health (Appendix Table 3).

Associations Between Early Life Sexual Trauma Exposures and Emotional Abuse in Older Age

Of 1745 women, 1532 returned leave-behind questionnaires, including 1515 who provided data about emotional abuse status. Of this sample, 123 (12%) reported ever feeling threatened or frightened by their current partners, and 169 (12%) reported ever feeling threatened or frightened by their family or friends. Overall, 248 (25%) of respondents reported potential emotional abuse from either their partner, family, or friends.

In adjusted models, women with a history of childhood sexual abuse had increased odds of reporting current emotional abuse by family or friends (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.39–3.83) and by their partner (OR 1.86, 95% CI 1.03–3.34). No significant associations were detected between unwanted first sexual experience and emotional abuse in older age (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In this nationally representative sample of community-dwelling older women, one in ten women reported experiencing childhood sexual abuse, while four in ten reported an unwanted first sexual experience. Accounting for established demographic risk factors for functional decline established in previous research, women with a history of childhood sexual abuse were more likely to experience pain during sexual intercourse, other urinary problems, and difficulty with multiple ADLs and IADLs in older age. Women with a history of unwanted first sexual experience were also more likely to report lacking pleasure during sex and difficulty with some ADLs/IADLs in older age. Our findings suggest that early sexual trauma may be an under-recognized marker of risk of genitourinary problems as well as general functional decline in older age, suggesting potential long-term consequences on older women’s health and well-being.

Although prior studies have documented adverse health effects of childhood sexual abuse,2, 5, 6, 35, 36 few have specifically examined associations between this abuse and later life health outcomes, with the majority of these investigating psychological rather than physical health outcomes. A prior survey in the UK found that a history of childhood sexual abuse was associated with mixed anxiety and depression, generalized anxiety disorder, phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation in men and women older than 50 years.11 In a longitudinal study of older adults in Ireland, childhood sexual abuse was associated with depression and anxiety in later life, in addition to conditions related to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction including cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and pain disorders.12 Another study examining an older psychiatric population linked severe childhood sexual abuse with increased cumulative medical illness burden and overall ADL and IADL impairment, but without distinguishing between types of ADLs or IADLs.10

Even fewer studies have investigated the potential long-term health consequences of an unwanted or forced first sexual experience in women. A recent large-scale analysis of US women found that forced sexual initiation was associated with increased rates of pelvic inflammatory disease, ovulatory/menstrual problems, and worse self-reported health, but analyses were confined to the reproductive years.24 Another cross-sectional analysis in Ireland found that both forced and “persuaded” sexual initiation were associated with worse measures of self-reported psychological and physical health, again focusing on women’s reproductive years.37, 38 To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined forced or coerced sexual initiation in relation to persistent health outcomes in older women.

Given the cross-sectional nature of our study, we cannot draw firm conclusions about causality or fully investigate the complex interplay between early life adversity and later life disability. However, our findings raise the possibility that early sexual trauma exposures can have lifelong health consequences. In particular, these findings are consistent with prior literature7 suggesting that early life exposures may place women on a trajectory towards increased risk of impairment in older age. Although preliminary, these insights provide additional incentive for healthcare providers to assess patients’ past exposure to sexual abuse irrespective of current age. Early detection may help clinicians gauge female patients’ risk of functional, genitourinary, or sexual decline later in life; aid in prevention; and allow for delivery of trauma-informed care. This may include efforts to help patients understand and address the effects of trauma on their health, as well as to facilitate connection to trauma-specific services that may help mitigate these health consequences.39

Our results also add to a growing body of evidence pointing to the potential overlap between exposure to early sexual trauma and other forms of later life abuse. A recent retrospective cohort study of older adults in Wisconsin found that early life victimization, including childhood sexual abuse, was associated with increased risk of elder victimization, although without distinguishing between different forms of elder abuse.8 A cross-sectional analysis of older Chinese-American adults found that a history of child maltreatment, including sexual abuse, was associated with twofold higher odds of elder abuse.40 Combined with these earlier findings, our results provide increased evidence of the interconnectedness of abuse across the lifespan.

This study benefits from a large, nationally representative sample of community-dwelling older women, examination of a diversity of outcomes relevant to aging-related function, and assessment of potential re-exposure of women to a different form of abuse in older age. However, several limitations should be noted. For childhood abuse, participants were not asked to quantify their experiences of sexual touching or age at first abuse. Although prior literature has shown a dose-dependent link between early sexual trauma and sexual revictimization in adulthood,41 this study did not evaluate additional forms of elder victimization beyond emotional abuse, or gather data surrounding revictimizations earlier in life. Due to the stigma surrounding sensitive topics such as abuse, early sexual trauma may also have been underreported by participants. With greater public discourse surrounding sexual trauma in the post-#MeToo era, future studies may reveal higher rates of acknowledged sexual trauma in women. Finally, given that this study examined numerous outcomes, there is potential that some associations may have appeared significant by chance.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our study identified associations between potentially traumatic early life sexual experiences and multiple forms of aging-related functional decline in a national sample of older community-dwelling women. Women with a history of early sexual trauma were also more likely to report emotional abuse later in life. These findings underline the importance of recognizing early sexual trauma as a potential lifelong risk factor for adverse health outcomes and other forms of victimization in older age, in order to guide trauma-informed care to women throughout the lifespan.

References

Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Basile KC, Walters ML, Chen J, Merrick MT. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization—national intimate partner and sexual violence survey, United States, 2011. Am J Public Health 2015;105(4):e11-e2. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302634

Thurston RC, Chang Y, Matthews KA, von Kanel R, Koenen K. Association of sexual harassment and sexual assault with midlife women’s mental and physical health. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179(1):48-53. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4886

Paras ML, Murad MH, Chen LP, et al. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009; 302(5):550-61. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1091

Snyder HN. Sexual assault of young children as reported to law enforcement: victim, incident, and offender characteristics. BJS Full Rep 2000;1-17.

Pulverman CS, Kilimnik CD, Meston CM. The impact of childhood sexual abuse on women’s sexual health: a comprehensive review. Sex Med Rev 2018;6(2):188-200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.12.002

Vezina-Gagnon P, Bergeron S, Frappier JY, Daigneault I. Genitourinary health of sexually abused girls and boys: a matched-cohort study. J Pediatr 2018;194:171-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.09.087

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14(4):245-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

Kong J, Easton SD. Re-experiencing violence across the life course: Histories of childhood maltreatment and elder abuse victimization. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2018;74(5):853-7. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby035

Ege MA, Messias E, Thapa PB, Krain LP. Adverse childhood experiences and geriatric depression: results from the 2010 BRFSS. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015;23(1):110-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.08.014

Talbot NL, Chapman B, Conwell Y, et al. Childhood sexual abuse is associated with physical illness burden and functioning in psychiatric patients 50 years of age and older. Psychosom Med 2009; 71(4): 417-22. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e318199d31b

Chou KL. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorders in middle-aged and older adults: evidence from the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. J Clin Psychiatry 2012; 73(11): e1365-71. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12m07946

Kamiya Y, Timonen V, Kenny RA. The impact of childhood sexual abuse on the mental and physical health, and healthcare utilization of older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 2016;28(3):415-22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610215001672

Waite LJ, Cagney KA, Dale W, et al.. National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP): Wave 2 and Partner Data Collection, [United States], 2010-2011. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2019. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR34921.v1.

O’Muircheartaigh C, English N, Pedlow S, Kwok PK. Sample design, sample augmentation, and estimation for Wave 2 of the NSHAP. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2014;69(Suppl 2): S15-S26. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu053

Suzman R. The national social life, health, and aging project: an introduction. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64(Suppl 1):i5-i11. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp078

Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. National Health and Social Life Survey, 1992: [United States]. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2008-04-17. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR06647.v2

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C, World Health Organization. WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes, and women’s responses. 2005. Available at: http://www.who.int/gender/violence/who_multicountry_study/en/. Accessed 14 July 2019

Sa Z, Larsen U. Gender inequality increases women’s risk of HIV infection in Moshi, Tanzania, J Biosoc Sci 2008;40(4):505-525. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002193200700257X

Erulkar A, Ferede A. Social exclusion and early or unwanted sexual initiation among poor urban females in Ethiopia. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2009;35(4):186-193. https://doi.org/10.1363/ipsrh.35.186.09

Waite LJ, Laumann EO, Das A, Schumm LP. Sexuality: measures of partnerships, practices, attitudes, and problems in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64(Suppl 1):i56-66. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp038

Yip SO, Dick MA, McPencow AM, Martin DK, Ciarleglio MM, Erikson EA. The association between urinary and fecal incontinence and social isolation in older women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(2):146.e1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.010

Erekson EA, Ciarleglio MM, Hanissian PD, Strohbehn K, Bynum JP, Fried TR. Functional disability and compromised mobility among older women with urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2015;21(3):170-5. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000136

Waetjen LE, Xing G, Johnson WO, Melnikow J, Gold EB. Study of Womenʼs Health Across the Nation. Factors associated with seeking treatment for urinary incontinence during the menopausal transition. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125(5):1071-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000808

Suskind AM, Cawthon PM, Nakagawa S, et al. Urinary incontinence in older women: the role of body composition and muscle strength: From the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65(1):42-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14545

Townsend MK, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, Grodstein F. The incidence of urinary incontinence across Asian, black, and white women in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):378.e1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.11.021

Yaffe MJ, Wolfson C, Lithwick M, Weiss D. Development and validation of a tool to improve physician identification of elder abuse: the Elder Abuse Suspicion Index (EASI). J Elder Abuse Negl 2008;20(3):276-300. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946560801973168

Kollia N, Caballero FF, Sánchez-Niubó A, et al. Social determinants, health status and 10-year mortality among 10,906 older adults from the English longitudinal study of aging: the ATHLOS project. BMC Public Health 2018;18(1):1357. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6288-6

Dunlop DD, Song J, Manheim LM, Daviglus ML, Chang RW. Racial/ethnic differences in the development of disability among older adults. Am J Public Health 2007;97(12):2209-2215. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.106047

Rohde P, Ichikawa L, Simon GE, et al. Associations of child sexual and physical abuse with obesity and depression in middle-aged women. Child Abuse Negl 2008;32(9):878-887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.11.004

Townsend MK, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, Grodstein F. BMI, Waist Circumference, and Incident Urinary Incontinence in Older Women. Obesity. 2008;16(4):881-886. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.14

Vincent HK, Vincent KR, Lamb KM. Obesity and mobility disability in the older adult. Obes Rev 2010;11(8):568-579. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00703.x

O’Muircheartaigh C, Eckman S, Smith S. Statistical design and estimation for the national social life, health, and aging project. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009;64B(Suppl 1): i12-i19. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp045

Yang E, Lisha NE, Walter L, Obedin-Maliver J, Huang AJ. Urinary incontinence in a national cohort of older women: implications for caregiving and care dependence. J Women's Health (Larchmt) 2018;27(9):1097-1103. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2017.6891

Pinto JM, Wroblewski KE, Kern DW, Schumm LP, McClintock MK. Olfactory dysfunction predicts 5-year mortality in older adults. PLoS One 2014;9(10):e107541. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107541

Rich-Edwards JW, Mason S, Rexrode K, et al. Physical and sexual abuse in childhood as predictors of early-onset cardiovascular events in women. Circulation. 2012;126(8):920-27. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.076877

Rapsey CM, Scott KM, Patterson T. Childhood sexual abuse, poly-victimization and internalizing disorders across adulthood and older age: Findings from a 25-year longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 2019;244:171-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.095

Hawks L, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Bor DH, Gaffney A, McCormick D. Association between forced sexual initiation and health outcomes among US women. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179(11):1551-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3500

McCarthy-Jones S, Bulfin A, Nixon E, O’Keane V, Bacik I, McElvaney R. Associations between forced and “persuaded” first intercourse and later health outcomes in women. Violence Against Women 2019;(5):528-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780121879322

Machtinger EL, Cuca YP, Khanna N, Rose CD, Kimberg LS. From treatment to healing: the promise of trauma-informed primary care. Womens Health Issues 2015;25(3):193-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2015.03.008

Dong X, Wang B. Associations of child maltreatment and intimate partner violence with elder abuse in a US Chinese population. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179(7): 889-96. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0313

Ports KA, Ford DC, Merrick MT. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual victimization in adulthood. Child Abuse Negl 2016;51:313-322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.08.017

Funding

The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (R37AG030481; R01AG033903). PL was funded by the Medical Student Training in Aging Research Program supported by the National Institute on Aging (T35AG026736). CG was funded by the VA Health Services Research & Delivery Career Development Award (IK2 HX002402). Funders were not involved in the analysis or interpretation of data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

None noted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations: American Geriatrics Society Annual Meeting, May 7th, 2020 (abstract published on-line after conference canceled), Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, May 8th, 2020 (abstract published on-line after conference canceled)

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lalchandani, P., Lisha, N., Gibson, C. et al. Early Life Sexual Trauma and Later Life Genitourinary Dysfunction and Functional Disability in Women. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 3210–3217 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06118-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06118-0