Abstract

Background

Medicaid managed care plans change provider networks frequently, yet there is no evidence about the performance of exiting providers relative to those that remain.

Objectives

To investigate the association between provider cost and quality and network exit.

Design

Observational study with provider network directory data linked to administrative claims from managed care plans in Tennessee’s Medicaid program during the period 2010–2016.

Participants

1,966,022 recipients assigned to 9593 unique providers.

Main Measures

Exposures were risk-adjusted total costs of care and nine measures from the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) were used to construct a composite annual indicators of provider performance on quality. Outcome was provider exit from a Medicaid managed care plan. Differences in quality and cost between providers that exited and remained in managed care networks were estimated using a propensity score model to match exiting to nonexiting providers.

Key Results

Over our study period, we found that 21% of participating providers exited at least one of the Medicaid managed care plans in Tennessee. As compared with providers that remained in networks, those that exited performed 3.8 percentage points [95% CI, 2.3, 5.3] worse on quality as measured by a composite of the nine HEDIS quality metrics. However, 22% of exiting providers performed above average in quality and cost and only 29% of exiting providers had lower than average quality scores and higher than average costs. Overall, exiting providers had lower aggregate costs in terms of the annual unadjusted cost of care per-member-month − $21.57 [95% CI, − $41.02, − $2.13], though difference in annual risk-adjusted cost per-member-month was nonsignificant.

Conclusions

Providers exiting Medicaid managed care plans appear to have lower quality scores in the year prior to their exit than the providers who remain in network. Our study did not show that managed care plans disproportionately drop high-cost providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Managed care has become the dominant method for the financing and delivery of services in Medicaid, with almost 80% of beneficiaries nationally enrolled in comprehensive plans.1 Under most Medicaid managed care (MMC) arrangements, states contract directly with health plans that, in turn, contract with networks of providers who deliver care for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health plans have considerable latitude to select and modify their provider networks and argue that the capacity to do so is among their primary tools to promote high-value care.2 Consequently, regulators have struggled with ensuring appropriate oversight and functioning of MMC plans while preserving the flexibility for plans to improve care processes through the modification of provider networks.3,4,5

How provider performance shapes contracting decisions between providers and MMC plans remains largely unknown, but is of critical importance to Medicaid programs. Providers have cited that changes to MMC plan networks lack transparency and plans offer limited feedback about the metrics that drive such decisions.6 Indeed, because payments to plans are capitated, plans might value providers who achieve cost savings over those who provide high-quality comprehensive care. On the other hand, MMC plans may value high-quality providers given plan accreditation requirements with the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), states’ use of quality performance for MC plan payment incentives, and public reporting of health plan quality performance, though high rates of churn among Medicaid recipients may blunt these otherwise strong incentives for plans to focus on high-quality care.7, 8 Perversely, cost and quality performance evaluations may also incentivize plans to value providers to select healthier patients or deselect sicker ones, as prior research has found that providers who serve greater proportions of vulnerable patients are less likely to be included in MMC networks.9

In spite of the growing appreciation of how the structure of provider networks impact patterns of care, no study has examined how objective measures of provider performance are associated with changes in provider networks. In this study, we examine the relationship between two measures of provider performance—quality of care and per capita costs of care—and network exit among providers participating in three large MMC plans in Tennessee. We also explored whether provider cost or quality was more strongly associated with network exit.

METHODS

Sources of Data and Study Population

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Yale University. Our primary data sources for this study were provider network directories and administrative claims data from three MMC plans participating in Tennessee during the period 2010–2016. The plans submitted monthly provider network directory data to the state, containing information on their contracted providers, including provider credentials, specialty, and geographic location. We linked this provider network data to administrative claims data using National Provider Identifiers.

We use administrative data that tracks recipients’ primary care provider over time to identify the patient panel for each provider in our sample. We preferred this attribution method relative to one based on a plurality of claims because it is consistent with the method used in many pay-for-performance models and it allowed specialists and non-MD providers to serve as a beneficiaries’ primary care provider, which has previously shown to be a common occurrence in Medicaid.10, 11 Because we did not have Medicare claims data, we removed recipients that were 65 years or older for whom Medicare was the primary payer. We also limited the yearly sample to individuals who were enrolled in Medicaid for at least 30 days in that calendar year in order to more precisely estimate per-member-per-month costs. Our final study population consisted of 9593 unique providers assigned to 1,966,022 unique recipients. We obtained additional data on geographic context from Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA’s) Federal Office of Rural Health Policy and The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS).

Variables

The primary dependent variable for this study was provider exit from a MMC plan. We categorized providers as exiters if they were listed in the plan’s monthly provider network directory at any point during a calendar year and then not included in the plan’s provider network directory during the subsequent year.

The primary independent variables were provider quality and cost in the year prior to exit as measured from administrative claims data. We focused on the year prior to exit because the NCQA reports Medicaid health plan quality performance at the annual level.12 To assess quality, we relied on nine measures of healthcare quality from NCQA’s Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). HEDIS is a quality measurement tool used by more than 90% of health plans nationally and is the basis of performance assessment for health plans within Medicaid, including Tennessee.12 Among the set of HEDIS measures, we selected primary care measures that could be exclusively constructed from administrative data. For each selected measure, we followed the technical specifications and look-back periods set out by CMS to construct the measures from recipient claims data at the recipient-year level.13, 14 For our aggregate quality measure, we summed all instances in which a provider delivered recommended care divided by all instances a provider was eligible for each of the nine measures, as constructed previously in the literature.15

We measure provider cost using the MMC plan paid amounts in our administrative claims data. We constructed three measures of provider cost: (1) total unadjusted cost of care per-recipient-per-month for the recipients in each provider’s panel; (2) risk-adjusted total cost of care per-recipient-per-month for the recipients in each provider’s panel; (3) proportion of a provider’s panel in the top 10% of the state’s costliest recipients, based on annual unadjusted total cost of care. All cost estimates were standardized to account for the amount of time beneficiaries were enrolled in the Medicaid program in a calendar year. To obtain risk-adjusted estimates of costs, we used estimates accounting for patient illness as calculated by the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index.16 Because pharmacy costs in Tennessee are carved out of MMC contract, we excluded them from our analysis. To ensure robust cost estimates, we limited our provider sample to those with at least 20 attributed patients.

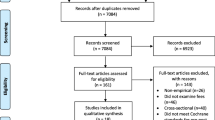

Statistical Analysis

To assess the comparability of exiting and nonexiting providers, we measured the baseline characteristics of the two groups. Discrete variables were compared with χ2 tests. To compare the quality and cost among exiting and nonexiting providers, we used a propensity score method to assess differences. The probability (i.e., the propensity score) that a provider would exit was estimated using a multivariable logistic regression model incorporating the following covariates related to our outcomes of cost and quality: (1) year; (2) provider practice zip code; (3) participation in a MMC health plan(s). Specifically, we matched each provider exiting a health plan with a provider who remained in that health plan for that year with similar propensity scores using nearest neighbor matching design without replacement. We matched on these three variables to identify providers that generally practiced in similar geographic areas with similar network adequacy factors that may be associated with exit. The mean standardized difference in all covariates was balanced after matching (i.e., < 10%) (eTable 1, eFig. 1).17 To account for the fact that providers could be enrolled in multiple plans in the same year, providers were matched at the provider-year-plan level. Consequently, providers who participated in multiple plans could be matched multiple times in a year and providers could be matched multiple times over the study period. However, providers who exited a plan in a given year were ineligible to be considered as a matched nonexiting provider in the same year for the other plans.

We used linear models on the matched propensity sample to examine the aforementioned cost and quality outcomes associated with exit. Estimates were clustered at the provider level to account for repeat observations over time. Additional models added controls for provider practice zip code, year, health plan, provider discipline and specialty in a stepwise fashion to account for the differential distribution of providers across these variables in our sample.

To examine whether exiting providers made up a substantially different proportion of the most or least costly providers, we constructed deciles of propensity-matched provider plan years according to risk-adjusted member-month patient panel cost and examined proportions within each decile of exiting versus nonexiting providers.

In a secondary analysis, we used a scatterplot to examine the association between cost and quality between exiting and nonexiting providers. We sought to determine whether a greater proportion of exiters provided care that was relatively high value (e.g., below median costs/above median quality) as compared with their counterparts. First, we z-score normalized the logged unadjusted cost per-member-month and the mean aggregated quality measure of both exiters and nonexiters. We then placed providers into quadrants of care, based on the median provider performance on both cost and quality and compared the share of exiting and nonexiting providers that fell within each quadrant of care.

We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our primary results. (1) Given that a small proportion of providers (< 2%) were associated with entity organizations (e.g., FQHCs), we repeated the analysis described above excluding recipients that were assigned to entity providers as opposed to individual providers. We also repeated the analyses (2) limiting our sample to include only those providers eligible for at least ten quality measures, (3) excluding recipients with less than 320 days of Medicaid MC enrollment for the year, (4) limiting our exiting provider observations to their first plan exit during the study period, (5) limiting our nonexiting provider observations to those providers who never exited during the study period, (6) limiting our providers to those practicing in rural areas, and (7) limiting our providers to those who exited after 10 months in the exit year. We constructed regression models that included provider panel size as a control variable in order to assess whether results were being driven by providers with more recipients attributed to them (eTable 2). For each additional analysis, we re-estimated the propensity score and created new matched subsamples with balanced observed covariates. Because healthcare spending is highly skewed, we tested the sensitivity of our results to using log cost. Finally, we examined the heterogeneity of our estimates by constructing separate regression models for providers exiting each of the three insurance plans. Data were analyzed using STATA, version 14.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Two-tailed p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Provider Characteristics and Frequency of Provider Exit

During the study period, there were 2799 plan exits among 1992 unique providers, representing 21% of the overall providers in our study. Exits occurred throughout the year, with 34% of exits occurring after October (eFig. 2). Compared with nonexiting providers, exiting providers were significantly more likely to be an adult primary care provider (p < 0.001) and less likely to be to be a pediatrician/pediatric specialist (p < 0.001). The propensity-matched sample attenuated the differences between the two provider groups (Table 1).

Association Between Provider Exit and Prior-Year Quality

Providers that exited MMC plans had lower performance in quality of care in the year prior to exit than providers that remained in the same plan (Fig. 1). Controlling for year, plan, provider practice zip code, and provider discipline and specialty, providers that exited performed significantly worse prior to exit than those that remained in terms of overall mean aggregate quality − 3.8 percentage points (pp) [95% CI, − 5.3 pp, − 2.3 pp], breast cancer screening every 2 years − 10.5 pp [95% CI, − 14.8 pp, − 6.2 pp], adolescent well visits − 4.4 pp [95% CI, − 6.4 pp, − 2.4 pp], and well child visits (ages 3–6) − 6.1 pp [95% CI, − 9.0 pp, − 3.3 pp]. Exiting providers did, however, perform significantly better on chronic medication monitoring than nonexiting providers 3.9 pp [95%CI, 0.4 pp, 7.4 pp]. We examined the sensitivity of these results to different sets of controls and found similar results except for chronic medication monitoring, which was insignificant when controlling for provider panel size (Table 2, eTable 5).

Mean difference in provider quality measures: propensity-matched sample regression results of exiting versus nonexiting providers. (Note: Refer to eTable 4 for unadjusted means for provider quality measure performance. Refer to eTable 5 for this figure’s numerical results as currently adjusted for year, provider plan, provider practice zip code, and provider characteristics.)

Association Between Provider Exit and Prior-Year Cost

The average per-member-per-month spending of our propensity-matched sample of providers was $231.29. Providers that exited MMC plans had lower average cost than nonexiting providers in the year prior to exit (Table 2). Relative to the providers that remained in networks, providers that exited were 1.3 pp [95% CI, 0.7, 1.9] less likely to have high-cost recipients in their panel (recipients in the top decile of state cost) and the recipients in their panels spent $21.57 [95% CI, $2.13, $41.02] less as measured by total unadjusted cost of care per-member-per-month. However, there was not a statistically significant difference in risk-adjusted total cost of care per-member-per-month − $3.53 [95% CI, − $20.90, $13.84] between providers that exited and remained in networks. Results were robust to the inclusion of additional controls (Table 2, eTable 5). Examining deciles of propensity-matched provider plan years according to risk-adjusted member-month patient panel cost, first decile being the least costly and tenth decile being the most costly, we see that exiting providers do not make up a substantially different proportion of the most costly or least costly deciles of providers (Fig. 2).

Relative Values of Cost and Quality

We assessed the relative performance of exiting and nonexiting providers on both quality and cost domains. Among exiting providers, 29% had patient panels who received lower than average quality and had above average costs (e.g., low value) in the year prior to exit (Fig. 3). In contrast, 22% of exiting providers delivered high-value care, delivering both above average quality and having a patient panel with below-average costs. Among matched providers that remained contracted with networks, 31% and 23% of providers fell in the low-value and high-value quadrants respectively. The remaining nonexiting providers (46%) performed below average in at least one of the domains of interest.

Scatterplots cost versus quality of propensity-matched exiting and nonexiting providers. Note: Cost axis is the z-score normalized logged unadjusted cost per-member-month and quality axis is the z-score normalized mean aggregated quality measure of both exiters and nonexiters. Providers then placed in quadrants of care based on cost and quality performance. For example, the upper right quadrant represents providers with high quality and high cost, whereas the lower left quadrant represents providers with low quality and low cost over the study period.

Sensitivity Analyses

We examined the effect of quality and cost for several subgroups to test the robustness of our primary finding (eTable 5). Quality measures for all sensitivity analyses were generally similar in magnitude and precision to our primary findings, except for chronic medication monitoring, which was insignificant in all sensitivity analyses. Our primary cost findings largely mirrored the results found in overall models.

DISCUSSION

We examined the extent to which provider performance predicted network changes in the MMC market of a large state. Over our study period, we found that one-fifth of participating providers exited a MMC plan. Exiting providers were, on average, associated with lower quality and cost in the year prior to their exit as compared with matched providers who remained in plans; however, there was no difference between exiters and nonexiters in risk-adjusted cost. Overall, however, network changes do not represent a silver bullet to improve plan performance as 77% of nonexiting providers performing below average in either the cost or quality domain.

We also find that while the majority of exiting providers delivered below-average quality and/or had panels with higher than average costs, almost one in four exiting providers appeared to deliver high-quality care at a lower than average per-member cost. This finding underscores the complexity of the challenge facing state Medicaid regulators. Plans are often forced to balance multiple factors when assessing the value of providers, and these factors may not entirely align with the wishes of patients or state regulators. Indeed, if value was the exclusive factor driving network changes, we might expect a substantially greater portion of low-value providers among exiters.

Finally, our results confirm previous studies that show that disruptions in the MMC program are frequent in nature.18 Changes in Medicaid provider networks inherently sever patient-provider relationships, although our study suggests that these short-term deficits for individual beneficiaries may be, in part, offset by the long-term improvements in the performance of providers that are available within the collective network.

While a previous research found that certain high-need patient case mixes may be less desirable to commercial plans, we find that, on average, selecting low-cost patient panels does not appear to be the driving force behind provider network changes in this Medicaid program.9 Selective contracting has become a hallmark of managed care, but it remains a process with limited regulatory oversight. The April 2016 CMS Rule called for increased accountability, fiscal integrity, and improved quality of care for Medicaid plans.19 Yet, the current administration has pulled back oversight and largely ceded the regulation of Medicaid networks to states.20 Although the black box of health plan network optimization commonly results in changes that are defensible based on objective dimensions, oversight is necessary to ensure that changes are neither arbitrary nor nefarious in nature. While our study sheds light on how cost and quality are associated with provider exit, there are several other ways plans may measure these domains to shape and optimize networks, such as patient satisfaction or preventable hospitalizations that deserve further research.

Our study has several limitations. First, our data could not reliably distinguish between provider versus plan-initiated exit, although plans have typically been tasked with managing networks to retain high-value providers. Second, our study only examined the association of provider exit with short-term indicators of provider performance; however, it is possible that plans and providers use longer-term data to inform decisions. Third, our risk adjustment only takes into account measurable and reported risk factors in the claims data and may be missing important risk factors that affect cost and quality. Fourth, we only examined a single state and our results may not generalize to other Medicaid programs. However, Tennessee’s MMC program offers several advantages. This state has a long-standing history with managed care and nearly all of its recipients are enrolled in comprehensive plans. Given the expanding role of managed care in Medicaid nationally, this study sheds light on a question of relevance to a growing number of states.

Our study highlights high rates of provider exit in MMC and suggests that provider networks appear to be shaped with intentionality. The providers who exited these MMC plans appear to have lower quality scores in the year prior to exit versus nonexiting providers. Nonetheless, there remain reasons for regulators to be vigilant in monitoring how plans shape and modify provider networks.

References

Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). Total Medicaid Managed Care Enrollment. KFF website. 2016. Accessed 21 May 2019. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/total-medicaid-mc-enrollment/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed 21 May 2019.

Corlette S, Volk J, Berenson R, Feder J. Narrow provider networks in new health plans: balancing affordability with access to quality care. Georgetown University Center on Health Insurance Reforms and The Urban Institute website, 2014. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/22601/413135-Narrow-Provider-Networks-in-New-Health-Plans.PDF. Accessed 13 March 2019.

Rosenbaum S, Schmucker S, Beckerman JZ. Policy Brief: Provider Networks and Access in Medicaid Managed Care: A Look at Federal and State Standards. The Commonwealth Fund Website. 2018. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2018/provider-networks-and-access-medicaid-managed-care-look-federal-and-state-standards. Accessed 13 March 2019.

Howard DH. Adverse effects of prohibiting narrow provider networks. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):591–3.

Baicker K, Levy H. How narrow a network is too narrow? JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):337–8.

Chain JJ Chain, J and the American Academy of Family Physicians to Karen Ignagni, President and CEO of America’s Health Insurance Plans, July 24, 2014. Letter. AAFP website. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/advocacy/coverage/medicaid/LetterAHIPNarroNetworks.pdf. Accessed 13 March 2019.

TennCare. 2018 Update to the quality assessment and performance improvement strategy. Accessed 21 May 2019. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents/qualitystrategy.pdf

Sommers BD, Graves JA, Swartz K, Rosenbaum S. Medicaid and marketplace eligibility changes will occur often in all states; policy options can ease impact. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(4):700–7.

Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Vranizan K, Jaffe D, Osmond D. Selection and exclusion of primary care physicians by managed care organizations. JAMA. 1998;279(9):675–79.

Ryan A, Linden A, Maurer K, Werner R, Nallamothu B. Commissioned White Paper: Attribution Methods and Implications for Measuring Performance in Health Care. National Quality Forum website. 2016. http://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/a-b/Attribution_2015-2016/Commissioned_Paper.aspx. Accessed 20 March 2019.

Tipirneni R, Rhodes KV, Hayward RA, et al. Primary care appointment availability and nonphysician providers one year after Medicaid expansion. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(6):427–31.

National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). NCQA health plan face sheet. NCQA website. Accessed 2/28/2019: https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services. Core Set of Children’s Health Care Quality Measures for Medicaid and CHIP: Technical specifications and resource manual for federal fiscal year 2017 reporting. Baltimore, MD: CMS, 2017.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services. Core Set of Adult Health Care Quality Measures for Medicaid and CHIP: Technical specifications and resource manual for federal fiscal year 2018 reporting. Baltimore, MD: CMS, 2018.

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–45.

AHRQ: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Elixhauser Comorbidity Software, Version 3.7. Accessed 2/25/2019: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp

Garrido MM, Kelley AS, Paris J, et al. Methods for constructing and assessing propensity scores. Health Serv Res; 2014;49(5):1701–20.

Ndumele CD, Staiger B, Ross JS, Schlesinger MJ. Network optimization and the continuity of physicians in Medicaid managed care. Health Affairs. 2018;37(6): 929–35.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Programs; Medicaid Managed Care, CHIP Delivered in Managed Care, and Revisions Related to Third Party Liability Final Rule. Federal Register website. 2016. Federal Register website. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/05/06/2016-09581/medicaid-and-childrens-health-insurance-program-chip-programs-medicaid-managed-care-chip-delivered. Accessed 20 May 2019.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP) Managed Care. Proposed Rule. Federal Register website. 2018. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/11/14/2018-24626/medicaid-program-medicaid-and-childrens-health-insurance-plan-chip-managed-care. Accessed 20 May 2019.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the research assistance of Christine Foster, M.P.Aff (Yale University) and Krzysztof Chwala (Yale University). Ms. Foster and Mr. Chwala received only salary compensation for their role in the study.

Funding

This publication was made possible by the Yale CTSA grant UL1TR000142 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Yale University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 173 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piwnica-Worms, K., Wallace, J., Lollo, A. et al. Association of Provider Performance with Changes in Insurance Networks. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 1997–2002 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05784-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05784-4