Abstract

Background

Narrow definitions of long-term opioid (LTO) use result in limited knowledge of the full range of LTO prescribing patterns and the rates of these patterns.

Objective

To investigate a model of new LTO prescribing typologies using latent class analysis.

Design

National administrative data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse were accessed using the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure. Characterization of the typology of initial LTO prescribing was explored using latent class analysis.

Participants

Veterans initiating LTO during 2016 through the Veteran’s Administration Healthcare System (N = 42,230).

Main Measures

Opioid receipt as determined by VA prescription data, using the cabinet supply methodology.

Key Results

Over one-quarter (27.7%) of the sample fell into the fragmented new long-term prescribing category, 39.8% were characterized by uniform daily new LTO, and the remaining 32.7% were characterized by uniform episodic LTO. Each of these three broad sub-groups also included two additional sub-groups (6 classes total in the model), characterized by the presence or absence of prior opioid prescriptions.

Conclusions

New LTO prescribing in the VA includes uniform daily prescribing, uniform episodic prescribing, and fragmented prescribing. Future work is needed to elucidate the safety and efficacy of these prescribing patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

The widely applied definition for the time frame in which opioid use becomes long-term is more than 90 days.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 However, the regularity of use within and beyond this period is less clear. For example, the joint Veteran’s Affairs and Department of Defense guidelines describe patients on long-term therapy as receiving “daily therapy,” whereas the Center for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines describe “use on most days.” This difference may be trivial if the overwhelming majority of patients in real-world practice settings who receive opioids over extended time periods exhibit daily or near-daily use. However, applying operational criteria allowing gaps between prescriptions of up to 50% (a minimal interpretation of “most days”) yield rates of long-term opioid (LTO) prescribing that are twice that of operational criteria requiring daily use.8 Thus, clinical or research applications requiring daily use to define LTO prescribing may be missing or excluding a large and important sub-group of individuals who receive opioids over-extended calendar periods, but at intervals consistent with less than daily use.9 A better understanding of such yet unexamined sub-groups could result in subsequent research to elucidate clinical trajectories in these sub-groups.

Opioid prescribing patterns can also exhibit irregularity in terms of involving multiple prescribers, different opioid agents, and varying prescription durations. These fragmented patterns may reflect a variety of clinical scenarios, such as unintended LTO prescribing, recurrent acute pain episodes, ineffectual intermittent therapy, gaps in accessing care, or potential misuse or diversion. Fragmented healthcare delivery is associated with diminished quality of care in general10, 11 and rates of high-risk use12,13,14 and overdose mortality15 with opioids specifically.

Our objective was to develop a typology of LTO prescribing; specifically, how patterns of irregular opioid prescribing cluster together within a broadly defined phenotype of LTO use consistent with CDC guidelines. Rather than starting with potentially skewed a priori assumptions about the nature of these clusters, we employed a latent class analysis (LCA) approach. LCA is a measurement model that allows for the identification of unobservable groups where individuals are classified into mutually exclusive and exhaustive types, based on their pattern of values in a set of categorical variables; in this case, variables representative of regularity and fragmentation of opioid prescribing. We restricted the analysis to patients with new LTO as we were most interested in prescribing patterns during the emergence of an LTO episode to elucidate the varied pathways by which LTO arises. Clinically, LTO could potentially occur intentionally or unintentionally and better classification of patterns of new LTO may facilitate future efforts to interrupt unintended LTO. As a first validation of the resulting typology model, we contrasted subsequent 1-year LTO persistence rates across typology classes. We chose 1-year persistence as an initial validation due to its clinical significance regarding potential adverse effects associated with prolonged opioid use (e.g., immunologic, hormonal, hyperalgesia, dependence, tolerance, etc.).16

METHODS

Patient Selection

The target population was Veterans initiating new LTO use during 2016. National administrative data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse were accessed using the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure. Schedule II opioid prescriptions dispensed by the VA during calendar years 2015 through 2017 were identified using outpatient pharmacy datasets. This included butorphanol, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, meperidine, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, oxymorphone, tapentadol, and schedule II dosage forms of codeine.

Opioid treatment episodes during this 3-year period were created using cabinet supply methodology.8, 17 Briefly, this method uses the pattern of refill dates and supply days dispensed to estimate the medication supply available to a patient on a daily basis over a specified time period. Consecutive prescriptions were considered part of the same episode if the number of zero cabinet supply days between prescriptions was less than or equal to the supply days of the preceding prescription. In other words, refill patterns consistent with opioid use on more days than not (≥ 50%) were considered part of a contiguous treatment episode, whereas longer gaps between prescriptions were considered discrete episodes. Congruent with the clinical definition of LTO therapy,1, 2, 18 an opioid treatment episode was categorized as long-term if the cumulative supply days dispensed during the episode exceeded 90 days.

Of 644,280 patients dispensed a schedule II opioid prescription in 2016, 84,162 (13.1%) had a long-term treatment episode that began in 2016. Patients with a LTO episode in the prior year were excluded (N = 41,932, 6.5%), resulting in a study population of 42,230 (6.6%) patients initiating new LTO use during 2016. The date of the first prescription of a new long-term treatment episode was defined as the episode index date. This study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board and the Iowa City Veterans Administration Research and Development Committee.

Typology Model

Our theoretical model for creating a typology of new LTO prescribing centered on an archetype of regular, daily use of a single medication under the supervision of a single prescriber. The extent to which a series of opioid prescriptions was consistent with, or deviated from, this archetype was captured using a set of metrics related to regularity in the timing of prescriptions and continuity of prescription characteristics (Supplemental Table 1). Metrics characterizing prescribing regularity included the number of discrete gaps in cabinet supply between prescriptions and the total number of zero cabinet days during the initiation of the episode. Metrics characterizing prescribing continuity included the number of unique values of dispensed supply days, the number of short duration prescriptions (< 28 days), the number of unique drugs dispensed, and the number of unique prescribers. All 6 metrics characterizing the initiation period were determined based on a 120-day period following and including the episode index date. As the duration requirement for a long-term opioid use is greater than 90 days, we selected a period of 120 days to capture prescribing patterns during the initial onset of the long-term episode. Alternative definitions for the duration of this follow-up period were explored, to a maximum of 180 days, and produced dichotomized latent class variables indicating very good agreement with the primary analysis, with kappa statistics exceeding 0.9 for all metrics.

While not part of the index episode, we were also interested in characterizing the pattern of opioid prescriptions observed in the 365 days leading up to the initiation of a long-term episode. Patients with a previous long-term episode were excluded by design, but patients could have received sub-threshold opioid exposure. The total volume of prescribing was captured using 4 prescribing metrics and continuity of care was captured using 2 metrics (Supplemental Table 1). We had no a priori expectation for whether patients initiating archetypal long-term therapy would have any particular degree of prior opioid exposure, relative to prescription patterns deviating from the archetype.

Statistical Analyses

The validity of our conceptual typology model was assessed using factor analysis with SAS procedure FACTOR (SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1). Each of the 12 prescribing metrics was coded in this analysis as a discrete variable ranging from 1 to 4 according to distributional breakpoints for each metric, where 1 reflected low values and 4 represented high values (Supplemental Table 2). A scree plot was used to inform the number of factors selected for the model based on each added factor having an eigenvalue exceeding 1 and a proportion of explained variance greater than 10%. Factor loadings were expressed using varimax orthogonal rotation.

Characterization of the typology of new LTO prescribing was explored using latent class analysis with SAS procedure LCA (SAS version 9.2).19 Each of the 12 prescribing metrics was coded in this analysis as a dichotomous variable according to distributional breakpoints (Supplemental Table 2). We examined models specifying 3 classes through 7 classes, selecting the final model based on diminishing incremental decreases in AIC, BIC, and G-squared fit statistics. In the final model, each patient was assigned to a latent class by the LCA procedure based on their best fit. To characterize these classes in a clinically meaningful manner, we tabulated the mean value for each of the 12 prescribing metrics, coded as continuous variables, and stratified by latent class.

As an initial validation of the latent class model, Kaplan-Meier survival curves for individual latent classes were constructed for time to opioid discontinuation using the SAS procedure LIFETEST. Differences in time to opioid discontinuation were contrasted across 3 pairwise latent classes using the log-rank test, with a Bonferroni corrected threshold of α = 0.017 for determining statistical significance. Discontinuation was defined as the end of the index long-term treatment episode, extending the previously described cabinet supply method out to 1 year following the episode index date, and censored at 365 days. Patients with continued opioid prescriptions through this 1-year follow-up period were classified as opioid persistent and persistence rates were reported across latent classes.

RESULTS

Factor Analysis

Evaluation of multiple factor solutions supported a 3-factor solution based on predetermined criteria. Each of the first three factors had eigenvalues greater than 1 and accounted for more than 10% of variance20 (Supplemental Table 3). In total, the 3-factor solution accounted for 76% of the variance of the full model. Factor loadings for the 12 opioid prescribing metrics (Table 1) were highly consistent with the proposed theoretical model (Supplemental Table 1). Factor 2 mapped precisely to Domain 1 of the theoretical model and included all 4 metrics related to continuity of care during the initiation of LTO prescribing, such as the count of unique supply day values and the number of unique prescribers. Factor 3 mapped precisely to Domain 2 of the theoretical model and included the 2 metrics related to the regularity of prescriptions during LTO initiation of the count of discrete gap periods and total zero cabinet supply days. While our theoretical model proposed two separate domains for pre-initiation metrics (domains 3 and 4), the factor analysis placed all 6 metrics together in one factor (factor 1).

Latent Class Analysis

Model Selection and Overview

In latent class analyses, fit statistics were assessed for models ranging from 3 to 7 classes (Supplemental Table 4). The largest decline across all 3 fit statistics occurred between the 5-class and the 6-class models, supporting the 6-class model as the best fit model. For example, BIC decreased by 46.9% between the 5- and 6-class models. The gain of going from 6 to 7-class model was not meaningful, as the decrease in BIC was only 1.7%.

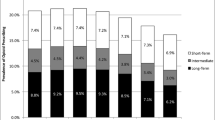

To aid the interpretation of the 6-class model (Fig. 1), each patient was assigned to a best-fit class and mean values for the 12 metrics were tabulated for each class (Table 2). These metrics are provided individually and conceptually grouped by the three factors indicated by the factor analyses. In reviewing the 6-class model, the most immediate observation was a sharp difference in post-initiation continuity metrics (factor 2). Specifically, classes 1 and 2 had markedly larger mean values across all metrics, compared to classes 3–6, including more prescriptions dispensed with < 28 supply days (mean = 2.3 versus 0.0) and more unique prescribers (mean = 2.9 versus 1.5). Thus, classes 1 and 2 were consistent with the concept of fragmented (irregular and discontinuous) long-term prescribing and accounted for 27.7% of patients initiating new LTO use. We labeled the remaining classes (classes 3–6) as uniform long-term prescribing.

Fragmented Prescribing

Over one-quarter (27.7%) of the sample fell into the fragmented long-term prescribing category (12.5% in class 1 and 15.2% in class 2) which was exemplified by poor continuity of care during initiation of their LTO episode, including multiple prescribers and opioid agents, as well as short and inconsistent dispensed supply days (Table 2). These patients also had notable gaps in cabinet supply during initiation, with means of 13.3 and 10.1 for classes 1 and 2, respectively. These classes differentiated from each other based on opioid use prior to initiation of long-term use, where class 1 was labeled as fragmented long-term prescribing with prior exposure and class 2 as fragmented long-term prescribing with minimal prior exposure.

Uniform Prescribing

While the four uniform prescribing classes shared similar values across post-initiation continuity metrics (factor 2), they differentiated from each other based on other metrics (Table 2). A first level of differentiation occurred with post-initiation regularity metrics (factor 3), where patients in classes 5 and 6 had less regularity in opioid prescriptions, spending a mean of 26.6 days with no apparent supply available on-hand during the initiation period. In contrast, patients in classes 3 and 4 had only 8.1 zero cabinet supply days. Thus, classes 3 and 4 were the closest to the archetype of uniform daily long-term prescribing, accounting for 39.8% of new long-term users overall, and 29.2% and 10.6%, respectively. Classes 3 and 4 differentiated from each other based on opioid use prior to initiation of long-term use. On average, patients in class 3 had a mean of 2.7 prescriptions with 58.7 days of opioid exposure during the year prior to long-term initiation. In contrast, class 4 had almost no prior opioid exposure, with a mean of 0.0 prescriptions and only 3.2 supply days. We therefore labeled class 3 as uniform daily long-term prescribing with prior exposure and class 4 as uniform daily long-term prescribing with minimal prior exposure.

As previously noted, classes 5 and 6 demonstrated characteristics consistent with uniform LTO prescribing in terms of minimal prescriptions of < 28 supply days (mean = 0.0) and few unique prescribers (mean = 1.4) but had notable gaps between prescriptions during the initiation of long-term use, with a mean of 2.2 discrete gap periods between prescriptions and a mean of 26.6 days with no apparent available supply. Observation of gaps between prescriptions could indicate either episodes of daily use interspersed with periods of no use, or regular but less than daily (or less than prescribed) use over time. We therefore labeled these classes as uniform intermittent-episodic prescribing, which collectively accounted for 32.7% of new LTO users. Classes 5 and 6 differentiated from each other based on opioid use prior to initiation of a long-term episode. Class 5 had substantially more prior opioid use across all pre-initiation metrics, including a mean of 134.9 supply days of opioids dispensed in the prior year, compared to 46.0 days for class 6. Thus, patients in class 5 had the largest volume of pre-initiation exposure, more than twice that of any other class, which is consistent with a history of prior intermittent-episodic exposure that became regular enough within a given time span to qualify as an episode of LTO use. We therefore labeled class 5 as uniform intermittent-episodic long-term prescribing with continued use and class 6 as uniform intermittent-episodic long-term prescribing with recent onset.

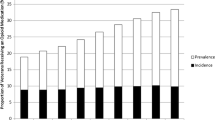

Survival Analysis

An initial assessment of the predictive validity of latent class analysis findings was conducted by contrasting 1-year persistence of the LTO treatment episode across identified classes (Table 2). The first contrast was across the 3 major classification categories: uniform daily long-term prescribing (classes 3 and 4), uniform intermittent-episodic long-term prescribing (classes 5 and 6), and fragmented long-term prescribing (classes 1 and 2). The respective 1-year persistence rates for these groups were 51.1%, 37.7%, and 28.9% and all pairwise comparisons in time to discontinuation using the log-rank test were statistically significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons (Table 2, Fig. 2). The second contrast was to compare the two sub-categories within each of the 3 major classification categories to each other. Within the uniform daily long-term prescribing category, patients with minimal prior opioid exposure had significantly higher persistence rates (class 4, 52.9%) than patients with prior exposure (class 3, 46.2%; log-rank test, Χ2 = 65.8; p < 0.001)). Similarly, within the uniform intermittent-episodic long-term prescribing category, patients with less prior exposure had higher persistence rates (class 6, 39.9%) than patients with more extensive prior exposure (class 5, 36.2%; log-rank test, Χ2 = 15.5; p < 0.001). Finally, prior exposure was not significantly associated with one-year opioid persistence among the two fragmented long-term prescribing groups (class 2, 29.0%; class 1, 28.7%; log-rank test, Χ2 = 0.45; p = 0.50).]-->

DISCUSSION

Building on prior opioid typology research,21 LTO prescribing does not appear to be a single unitary construct but encompasses a heterogenous collection of prescribing patterns. Three major patterns emerged from a latent class analysis and were characterized as uniform daily, uniform episodic, and fragmented opioid prescribing. These three patterns were associated with differing rates of persistent LTO at 1 year; uniform daily was the most common (51%) and fragmented the least, but still a large sub-set (29%). Each major class further differentiated into two sub-classes based on the volume of opioid prescriptions received prior to, but not as part of, the index new long-term episode. The major class labeled as uniform daily prescribing was consistent with the historical archetype of LTO therapy, characterized as daily use of a single medication under the supervision of a single prescriber. However, this class accounted for less than half (40%) of new long-term episodes.

More than one-quarter (27.7%) of new long-term episodes fell into the major class of fragmented prescribing, which was characterized by multiple providers, multiple opioid agents, and variable dispensed supply days. Fragmented healthcare delivery (which may include dual use of VA and other healthcare systems) is associated with poorer care in general10, 11 and rates of high-risk use13, 14 and overdose mortality15 with opioids specifically. An important limitation of this study was that opioid receipt from sources outside VHA could not be observed; thus, our findings may underestimate the proportion of patients with fragmented opioid prescribing. As fragmentation may arise from attempts to alleviate barriers for patients in accessing health services, further research is needed to determine the optimum balance between the potential harms of fragmented opioid prescribing and the benefits of wider access to pain management services.

The final major class was uniform episodic prescribing, which accounted for about one-third (32.7%) of new LTO episodes. Like the uniform daily class, the uniform episodic class was characterized by few prescribers and consistent drug and supply days dispensed. However, patients in the uniform episodic class experienced substantially more zero cabinet supply days between prescriptions. These periods were not of sufficient duration to indicate a distinct episode of care but suggested that patients were consistently taking opioids on a less than daily basis. This could represent a range of possibilities such as intentional episodic prescribing, careful patient-led self-management with an appropriate pro re nata (PRN) regimen, or inconsistent care. The uniform episodic class further differed from other classes in having a substantially larger volume of opioid prescribing prior to the index long-term episode. This suggests that opioids are sometimes prescribed on an intermittent or episodic basis over extended periods of time. Further research is needed to assess the efficacy and safety of purposeful prescribing of long-term opioids in less-than-daily patterns, particularly as this practice was common among new long-term users (32.7%), is often neglected in the literature by potentially over-restrictive exclusion criteria and is generally unacknowledged by policy discussions and clinical practice guidelines.

This study had some additional limitations that warrant consideration. As prescribing behavior is influenced by laws, policies, and other environmental factors at the state and local level, it is unclear whether prescribing patterns observed in the VHA will necessarily generalize to other healthcare systems. The VA is an integrated system that has made significant efforts in recent years to reduce the prevalence and associated risks of LTO,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 including implementing the Opioid Safety Initiative, the opioid overdose and naloxone distribution (OEND) program, the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) tool, and increasing access to non-pharmacological pain management options.22, 23, 25 In addition, this study was restricted to new LTO prescribing which accounted for about 15% of LTO prescribing in the VA in 2016,29 and future research is needed to determine whether these same patterns would generalize to all prevalent LTO prescribing. Based on differences in 1-year persistence rates observed in this study, it is likely that, at a minimum, the distribution patterns would be different, with greater representation of the uniform daily pattern among prevalent LTO users. Finally, our methods were susceptible to a priori assumptions inherent in the current conceptual definition of what constitutes LTO prescribing in terms of regularity and duration of use. While we took a broad approach in creating our operational definition, our finding suggests that the current concept of LTO prescribing may be overly restrictive. This idea further extends to the substantial proportion of patients that fall into an ill-defined category of intermediate use, who do not meet current criteria for long-term use but with exposure beyond that typically considered to be acute use.29

CONCLUSION

New LTO prescribing encompasses a spectrum of patterns which clustered into three main categories: uniform daily, uniform episodic, and fragmented prescribing. The current concept of LTO as requiring daily or near-daily use, as well as a priori operational research definitions of LTO, may exclude important subgroups of patients; examining the full range of new LTO allows for greater understanding of the full continuum of opioid prescription patterns. The typology approach described in this paper forms the foundation for future work validating these sub-categories of LTO prescribing, including contrasts of patient characteristics and clinical outcomes across groups.

References

Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2016. 65(RR-1):1–49.

Affairs, D.o.V. and D.o. Defense. VA/DoD CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR OPIOID THERAPY FOR CHRONIC PAIN, Version 3.0. 2017.

Quanbeck A, et al. A randomized matched-pairs study of feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of systems consultation: a novel implementation strategy for adopting clinical guidelines for Opioid prescribing in primary care. Implement Sci, 2018. 13(1):21.

Liebschutz JM, et al. Improving Adherence to Long-term Opioid Therapy Guidelines to Reduce Opioid Misuse in Primary Care: A Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med, 2017. 177(9):1265–1272.

Dorflinger L, et al. A partnered approach to opioid management, guideline concordant care and the stepped care model of pain management. J Gen Intern Med, 2014. 29 Suppl 4:870–6.

Deyo RA, et al. Association Between Initial Opioid Prescribing Patterns and Subsequent Long-Term Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients: A Statewide Retrospective Cohort Study. J Gen Intern Med, 2017. 32(1):21–27.

Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of Initial Prescription Episodes and Likelihood of Long-Term Opioid Use - United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2017. 66(10):265–269.

Mosher HJ, Richardson KK, Lund BC. The 1-Year Treatment Course of New Opioid Recipients in Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med, 2016.

Goplen CM, et al. The Influence of Allowable Refill Gaps on Detecting Long-Term Opioid Therapy: An Analysis of Population-Based Administrative Dispensing Data Among Patients with Knee Arthritis Awaiting Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Manag Care Spec Pharm, 2019. 25(10):1064–1072.

Frandsen BR, et al. Care fragmentation, quality, and costs among chronically ill patients. Am J Manag Care, 2015. 21(5):355–62.

Stange KC. The problem of fragmentation and the need for integrative solutions. Ann Fam Med, 2009. 7(2): 100–3.

Young SG, et al. Doctor hopping and doctor shopping for prescription opioids associated with increased odds of high-risk use. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 2019.

Gellad WF, et al. Impact of Dual Use of Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D Drug Benefits on Potentially Unsafe Opioid Use. Am J Public Health, 2018. 108(2):248–255.

Becker WC, et al. Multiple Sources of Prescription Payment and Risky Opioid Therapy Among Veterans. Med Care. 2017;55 Suppl 7 Suppl 1:S33-S36.

Moyo P, et al. Dual Receipt of Prescription Opioids From the Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D and Prescription Opioid Overdose Death Among Veterans: A Nested Case-Control Study. Ann Intern Med, 2019.

Benyamin R, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician, 2008. 11(2 Suppl):S105–20.

Becker WC. Rigorous Epidemiologic Work Shows Positive Impact of VHA's Efforts to Rein in Opioid Prescribing. Pain Med, 2016.

Taxonomy, I.A.f.t.S.o.P.S.o. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Pain Supplement, 1986(3):S1–226.

Lanza ST, et al. Proc LCA & Proc LTA users' guide (Version 1.3.2). 2015, University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State. Available from https://www.methodology.psu.edu/downloads/proclcalta/. Accessed 6 Feb 2019.

Wilcox R. Introduction to Robust Estimation and Hypothesis Testing Fourth Edition. 2017: Elsevier.

Von Korff M, et al. De facto long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain. Clin J Pain, 2008. 24(6):521–7.

Lin LA, et al. Impact of the Opioid Safety Initiative on opioid-related prescribing in veterans. Pain, 2017. 158(5):833–839.

Oliva EM, et al. Opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution: Development of the Veterans Health Administration's national program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003), 2017. 57(2S):S168-S179 e4.

Oliva EM, et al. Patient perspectives on an opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution program in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Subst Abus, 2016. 37(1):118–26.

Oliva EM, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration's Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv, 2017. 14(1):34–49.

Merlin JS, et al. Managing Concerning Behaviors in Patients Prescribed Opioids for Chronic Pain: A Delphi Study. J Gen Intern Med, 2018. 33(2):166–176.

Becker, W.C., et al., Evaluation of an Integrated, Multidisciplinary Program to Address Unsafe Use of Opioids Prescribed for Pain. Pain Med, 2017.

Becker WC, et al. Mixed methods formative evaluation of a collaborative care program to decrease risky opioid prescribing and increase non-pharmacologic approaches to pain management. Addict Behav, 2018.

Hadlandsmyth K, et al. Decline in Prescription Opioids Attributable to Decreases in Long-Term Use: A Retrospective Study in the Veterans Health Administration 2010-2016. J Gen Intern Med, 2018. 33(6):818–824.

Acknowledgments

The work reported here was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration and the Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Service through the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) Center (CIN 13-412). The sponsors did not have any role in the study design, methods, analyses, and interpretation, or in preparation of the manuscript and the decision to submit it for publication. The authors thank Gosia Clore and Vanessa Au for their assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 19 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hadlandsmyth, K., Mosher, H., Bayman, E.O. et al. A Typology of New Long-term Opioid Prescribing in the Veterans Health Administration. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 2607–2613 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05749-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05749-7