Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) screening is an evidence-based strategy to reduce CRC-related mortality.

Objective

This study identifies physician and participant characteristics, as well as previous FIT values associated with premature FIT usage.

Design

This is a retrospective review of all FITs ordered from January 1, 2016, until June 30, 2017. For each ordered FIT, the participant’s chart was reviewed to identify if a previous FIT had occurred in the prior 21 months. A premature FIT was defined as an ordered test with a negative FIT in the preceding 21 months.

Participants

Screening participants were average risk for CRC, aged 50–74, and had a FIT ordered by their primary care provider in British Columbia, Canada.

Main Measures

The BC College of Physicians and Surgeons’ database was used to identify the location of referring physician, date of graduation from medical school, and gender. The participant’s age, gender, and value of previous FIT were recorded. Physician and participant variables and previous FIT value were examined with logistic regression to identify associations with premature FIT ordering.

Key Results

In total, 385,375 FITs were ordered during this period with 116,727 representing participants returning following a previous negative FIT. In total, 35,148 (30.1%) returned early for screening. Men were more likely to return early than women (OR 1.14; 95% CI 1.11–1.17; p < 0.0001). Male physicians were more likely to order premature FITs (OR 1.15; 95% CI 1.06–1.24; p < 0.0001). A higher quantitative FIT value (ng/mL) of the previous FIT was also associated with early screening (OR 1.11; 95% CI 1.09–1.14; < 0.0001).

Conclusions

This study found that approximately 30% of FIT tests, ordered for CRC screening, were ordered before they were due. This may lead to wasted resources, unnecessary participant stress, and unwarranted patient risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in North America.1, 2 Multiple randomized prospective studies have showed a reduction in colorectal cancer (CRC) mortality from fecal occult blood testing (FOBT).3,4,5 Endoscopic removal of precursor lesions has been shown to reduce the risk of developing cancer.6 The fecal immunochemical test (FIT) has replaced the previous guaiac fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) as the noninvasive screening test of choice.7,8,9,10,11 The U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer has recommended annual FIT testing12 as one of the modalities for CRC screening whereas the Canadian Task Force on Preventative Health Care recommends biennial screening.13

Cancer screening programs have studied participation rates14, 15 and interventions to improve screening rates.16,17,18,19 Once screened, participants are recalled for re-screening at appropriate intervals. Quality initiatives such as automated reminders20 are becoming standard, but physicians can order FITs independent of recommended intervals. The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care recommends FIT every 2 years based on the reduction in colon cancer mortality with biennial gFOBT.21 The 2-year interval may improve adherence, but this is unproven.22 The pooled sensitivity for a one-time FIT in the detection of CRC is 79%.23

VHA studies have assessed early return for repeat screening in the USA. Fisher et al. studied gFOBTs ordered by primary care professionals at a single VHA Medical Center. They reported that 7% of the 500 FOBTs ordered were inappropriate because the screening participant had a colonoscopy in the prior 5 years.24 Ahmed et al. performed a single-center retrospective chart review of patients who had gFOBT who had already had a total colon examination.25 Powell et al. identified a specific realm of inappropriate testing whereby screening participants are tested with a gFOBT prior to being recalled after a previous negative gFOBT result.26 The authors identified that inappropriate screening strains resources, adds unnecessary stress to participants, and exposes participants to risk. Partin et al. recommended that additional studies are required to look at rates of overuse of noninvasive CRC screening modalities.27, 28

A FIT is offered in British Columbia (BC) for all patients between the ages 50 and 75 at an average risk of CRC. Participants with a previous negative FIT in the program are recalled for repeat FIT every 2 years. A recall letter is sent by the BC Colon Screening Program (BCCSP) at 22 months from the last negative FIT. Patients then see their primary care provider to receive a FIT requisition. Once the test has been completed, results are sent to the BCCSP and positive FITs are referred for colonoscopy consideration. However, physicians in the screening program may order FITs for their patients prior to the 2-year recall. This study investigates factors associated with premature FIT ordering.

METHODS

The study was a retrospective review of all FITs performed in the BC Colon Screening Program from January 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017. We defined a premature FIT as one in which a participant had a negative FIT in the preceding 21 months. The study was approved by the BC Cancer Agency Research Ethics board on October 6, 2017.

The BC Colon Screening Program (BCCSP) was commenced in 2013 and is a publicly funded program available to average-risk individuals, age 50 to 75 years. Participants are screened every 2 years with a quantitative FIT (NS-Plus, Alfresa, Japan) at a cutoff of positivity of 50 ng/mL buffer (10 μg/g feces). Physicians and participants have access to their quantitative FIT value. Screening participant data, including FIT values, is collected by the BC Cancer Agency and maintained in the BCCSP database.

Physician characteristics including gender, location of training, year of graduation from medical school, and location of practice were from the BC College of Physicians and Surgeons’ physician directory and adhered to the College’s acceptable use policy. Classification of urban versus rural location of practice was determined by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer definition.29 The Postal Code Conversion File Plus (PCCF +, Statistics Canada, Ottawa) was used to obtain population size and access to services by postal code. The categories were collapsed into a binary variable of rural or urban. Postal codes beginning with V0 that could not be assessed by PCCF+ were assigned as rural.

The association between patient, physician, year of return, and test characteristics with premature FIT was investigated using logistic regression. To control for the repeat nature of analyzing the same referring physician for multiple patients, a generalized estimating equation (GEE) was used. For this data, an exchangeable correlation structure was specified. Interactions between clinically significant independent variables were assessed. Significance threshold was p ≤ 0.05. Cluster analysis was used to categorize variables. Gower distance was calculated for patient age, FIT value, and year of medical graduation, considering the proportion of inappropriate FITs for each value. A partitioning around mediods (PAM) algorithm was used and the number of clusters chosen maximized silhouette width. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4. (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) R version 3.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna30).

RESULTS

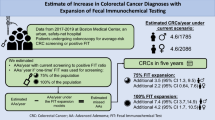

In total, 385,375 FITs were ordered during this period with 116,727 being returns from a previous negative FIT. In total, 35,148 (30.1%) patients returned early for screening (Fig. 1). The percentage of premature FITs changed over the study period. From January 2016 to June 2016, the proportion of premature FITs was 48.26% compared with 27.34% from July to December. The proportion was even lower in 2017 at 21.17% from January to June 2017. Characteristics of the screening participants returning for FIT testing are provided in Table 1 and characteristics of physicians ordering premature FITs are presented in Table 2.

With regard to premature FITs (Table 3), male participants were more likely to receive premature FIT orders than females (OR 1.14; 95% CI 1.11–1.17; p < 0.0001). Younger age was associated with premature return (OR 1.04; 95% CI 1.01–1.06; p = 0.003). In terms of physician characteristics (Table 3), male physicians were more likely to order premature FITs (OR 1.15; 95% CI 1.06–1.24; p < 0.0001). Physicians in urban practices who went to medical school in Canada were more likely to order premature FITs (OR 1.32; 95% CI 1.11–1.58; p = 0.002). The BC Colon Screening Program defines a positive FIT as greater than or equal to 50 ng/mL buffer. A higher value of the previous negative FIT, defined as 20–49 ng/mL compared with 0–19 ng/mL, was associated with early repeat FITs (OR 1.11; 95% CI 1.09–1.14; p < 0.0001) (Table 3). Patients screened in the first half of 2016 had the highest association with premature testing (OR 3.35 95% CI 3.18–3.52; p < 0.0001).

Of the premature FITs, 27.3% were ordered by a different physician from the previous FIT (Table 4). Having a different provider order, the FIT was associated (OR 1.26; 95% CI 1.19–1.35; p < 0.0001) with early repeat FIT. Interactions between independent variables were investigated. Physician gender had no interaction with patient gender, degree year, degree location, patient age, or location of practice. Patient gender was associated with physician degree year, but the relationship was not significant. There was a significant interaction between location of medical training and location of practice.

CONCLUSIONS

Males, screening participants aged 50–62, and those with a higher previous quantitative FIT were more likely to get an early FIT. Male physicians and physicians in urban practices were more likely to order early FITs. Compared with other studies, our proportion of premature screening of 30.1% is high. Powell et al.’s study looked at annual FOBTs and reported that 13.9% of the 901,292 FOBTs were not due for screening as the patient had a FOBT within the prior 10 months, colonoscopy within the prior 9.5 years, or a sigmoidoscopy or barium enema within the prior 4.5 years.26 In Partin’s study using an annual FOBT for screening, 8% of the FOBTs were coded as overused if their last prior FOBT occurred in the preceding 10 months.28

The direct risk of early colorectal screening is potential for the serious complications of colonoscopy.26 Other consequences of early screening include inconvenience and subjective stress to the screening participant. For screening colonoscopists and the BC CSP, the early FITs represent a strain on resources and could inflate wait times for other individuals in need of screening.

A number of explanations are likely contributing to early return in our study. The spike at 1 year (Fig. 1) may be due to the legacy of 2013 provincial recommendation for FIT every 1 to 2 years, revised to specify every 2 years in 2016.31 From 2016 to 2017, the percentage of premature FITs significantly decreased. This likely represents uptake and familiarity of the 2016 guidelines by ordering physicians. In addition, as wait times for publicly funded colonoscopies are long,32 primary care physicians may order FIT early for diagnostic purposes, anticipating an expedited procedure for a positive FIT within the BCCSP. Primary care physicians may have also determined that a higher value of a previous negative FIT justified an earlier repeat FIT, perhaps supported by participant concerns as BC citizens can access their laboratory results online and could request repeat testing. Finally, physicians often do not access tests ordered by a different physician unless they work in joint practices or review the separate provincial database called CareConnect. Therefore, a patient in an urban setting who sees multiple doctors may have a FIT ordered because the physician is not aware that a patient is up to date with screening. This is supported by the increased premature FIT associated with different ordering physicians.

The literature on the harms of cancer screening is evolving. Authors have clarified the terminology on the harms of screening33 and types of inappropriate screening.26 This study only focuses on the interval of CRC screening and early return. This study does not address other aspects of inappropriate screening such as ordering FIT for higher-risk participants in a colonoscopy surveillance program, screening participants with limited life expectancy, individuals at higher risk for CRC (i.e., IBD), and those with a family history of CRC or with symptoms of CRC. Our data is also not sensitive enough to identify participants returning for FIT with an earlier FIT performed outside the BCCSP. Colon cancer screening with colonoscopy alone is also not addressed in this study. FITs ordered by physicians who did not have office information available on the BC College of Physicians and Surgeons’ website were excluded. Because of the above factors, it is likely that 30.1% is an underestimation of the true burden of inappropriate screening FITs ordered in BC.

We propose that the amount of premature screening be included as a quality measure in the evaluation of CRC screening programs. We recommend other programs adopt our practice of using a report card to disseminate individual and aggregate data for participating physicians. We suggest there should be mechanisms in CRC screening programs to prevent against ordering FITs for diagnostic purposes. A possible mechanism to enforce adherence to guideline would be to restrict reimbursement for premature FITs. Despite the use of an organized CRC screening program, 30% of FITs ordered in the BCCSP were premature. This finding represents an objective target for quality improvement initiatives to reduce the burden of overscreening for CRC.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017. May 6;67(3):177–93.

Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2017. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2017. http://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/CW/cancer%20information/cancer%20101/Canadian%20cancer%20statistics/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2017-EN.pdf. Accessed May 9, 2019.

Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM, Ederer F. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota colon cancer control study. N Engl J Med. 1993 May 13;328(19):1365–71.

Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW, James PD, Mangham CM. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996 Nov 30;348(9040):1472–7.

Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jorgensen OD, Sondergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996 Nov 30;348(9040):1467–71.

European Colorectal Cancer Screening Guidelines Working Group, von Karsa L, Patnick J, Segnan N, Atkin W, Halloran S, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Malila N, Minozzi S, Moss S, Quirke P, Steele RJ, Vieth M, Aabakken L, Altenhofen L, Ancelle-Park R, Antoljak N, Anttila A, Armaroli P, Arrossi S, Austoker J, Banzi R, Bellisario C, Blom J, Brenner H, Bretthauer M, Camargo Cancela M, Costamagna G, Cuzick J, Dai M, Daniel J, Dekker E, Delicata N, Ducarroz S, Erfkamp H, Espinas JA, Faivre J, Faulds Wood L, Flugelman A, Frkovic-Grazio S, Geller B, Giordano L, Grazzini G, Green J, Hamashima C, Herrmann C, Hewitson P, Hoff G, Holten I, Jover R, Kaminski MF, Kuipers EJ, Kurtinaitis J, Lambert R, Launoy G, Lee W, Leicester R, Leja M, Lieberman D, Lignini T, Lucas E, Lynge E, Madai S, Marinho J, Maucec Zakotnik J, Minoli G, Monk C, Morais A, Muwonge R, Nadel M, Neamtiu L, Peris Tuser M, Pignone M, Pox C, Primic-Zakelj M, Psaila J, Rabeneck L, Ransohoff D, Rasmussen M, Regula J, Ren J, Rennert G, Rey J, Riddell RH, Risio M, Rodrigues V, Saito H, Sauvaget C, Scharpantgen A, Schmiegel W, Senore C, Siddiqi M, Sighoko D, Smith R, Smith S, Suchanek S, Suonio E, Tong W, Tornberg S, Van Cutsem E, Vignatelli L, Villain P, Voti L, Watanabe H, Watson J, Winawer S, Young G, Zaksas V, Zappa M, Valori R. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis: Overview and introduction to the full supplement publication. Endoscopy . 2013;45(1):51–9.

Nakajima M, Saito H, Soma Y, Sobue T, Tanaka M, Munakata A. Prevention of advanced colorectal cancer by screening using the immunochemical faecal occult blood test: A case-control study. Br J Cancer. 2003 Jul 7;89(1):23–8.

Lee KJ, Inoue M, Otani T, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane S, Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Colorectal cancer screening using fecal occult blood test and subsequent risk of colorectal cancer: A prospective cohort study in japan. Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31(1):3–11.

Zappa M, Castiglione G, Grazzini G, Falini P, Giorgi D, Paci E, Ciatto S. Effect of faecal occult blood testing on colorectal mortality: Results of a population-based case-control study in the district of florence, italy. Int J Cancer. 1997 Oct 9;73(2):208–10.

Allison JE, Sakoda LC, Levin TR, Tucker JP, Tekawa IS, Cuff T, Pauly MP, Shlager L, Palitz AM, Zhao WK, Schwartz JS, Ransohoff DF, Selby JV. Screening for colorectal neoplasms with new fecal occult blood tests: Update on performance characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007 Oct 3;99(19):1462–70.

van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, van Oijen MG, Fockens P, van Krieken HH, Verbeek AL, Jansen JB, Dekker E. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2008 Jul;135(1):82–90.

Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T, Levin TR, Lieberman D, Robertson DJ. Colorectal cancer screening: Recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017 Jul;153(1):307–23.

Bacchus CM, Dunfield L, Gorber SC, Holmes NM, Birtwhistle R, Dickinson JA, Lewin G, Singh H, Klarenbach S, Mai V, Tonelli M, Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for colorectal cancer in primary care. CMAJ. 2016 Mar 15;188(5):340–8.

Vernon SW. Participation in colorectal cancer screening: A review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997 Oct 1;89(19):1406–22.

van der Vlugt M, Grobbee EJ, Bossuyt PM, Bongers E, Spijker W, Kuipers EJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Essink-Bot ML, Spaander MC, Dekker E. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: Four rounds of faecal immunochemical test-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2017 Jan 3;116(1):44–9.

Rat C, Pogu C, Le Donne D, Latour C, Bianco G, Nanin F, Cowppli-Bony A, Gaultier A, Nguyen JM. Effect of physician notification regarding nonadherence to colorectal cancer screening on patient participation in fecal immunochemical test cancer screening: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017 Sep 5;318(9):816–24.

Singal AG, Gupta S, Skinner CS, Ahn C, Santini NO, Agrawal D, Mayorga CA, Murphy C, Tiro JA, McCallister K, Sanders JM, Bishop WP, Loewen AC, Halm EA. Effect of colonoscopy outreach vs fecal immunochemical test outreach on colorectal cancer screening completion: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017 Sep 5;318(9):806–15.

Pignone M, Miller DP, Jr. Using outreach to improve colorectal cancer screening. JAMA. 2017 Sep 5;318(9):799–800.

Miller DP, Jr, Denizard-Thompson N, Weaver KE, Case LD, Troyer JL, Spangler JG, Lawler D, Pignone MP. Effect of a digital health intervention on receipt of colorectal cancer screening in vulnerable patients: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med . 2018 Apr 17;168(8):550–7.

Chao HH, Schwartz AR, Hersh J, Hunnibell L, Jackson GL, Provenzale DT, Schlosser J, Stapleton LM, Zullig LL, Rose MG. Improving colorectal cancer screening and care in the veterans affairs healthcare system. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2009 Jan;8(1):22–8.

Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, Lederle FA, Bond JH, Mandel JS, Church TR. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013 Sep 19, [cited Feb 12, 2019];369(12):1106–14.

Bacchus CM, Dunfield L, Gorber SC, Holmes NM, Birtwhistle R, Dickinson JA, Lewin G, Singh H, Klarenbach S, Mai V, Tonelli M. Recommendations on screening for colorectal cancer in primary care. CMAJ. 2016 03 15, [cited Feb 12, 2019];188(5):340–8.

Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, et al. Accuracy of fetal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer; systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:171–81.

Fisher DA, Judd L, Sanford NS. Inappropriate colorectal cancer screening: Findings and implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Nov;100(11):2526–30.

Ahmed, F, Murthy, UK, Szyjkowski, RD, et al. Inappropriate use of fecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening in primary care practices at a VA hospital. Gastroenterology 2001;120 (suppl 1):A604–A605.

Powell AA, Saini SD, Breitenstein MK, Noorbaloochi S, Cutting A, Fisher DA, Bloomfield HE, Halek K, Partin MR. Rates and correlates of potentially inappropriate colorectal cancer screening in the veterans health administration. J Gen Intern Med 2015 Jun;30(6):732–41.

Holden DJ, Jonas DE, Porterfield DS, Reuland D, Harris R. Systematic Review: Enhancing the Use and Quality of Colorectal Cancer Screening. Ann Intern Med. ;152:668–676.

Partin MR, Powell AA, Bangerter A, Halek K, Burgess JF, Jr, Fisher DA, Nelson DB. Levels and variation in overuse of fecal occult blood testing in the veterans health administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Dec;27(12):1618–25.

Canadian Partnership Against Cancer 2014. Examining Disparities in Cancer Control: A System Performance Special Focus Report. www.cancerview.ca/systemperformance report. Published February 2014. Accessed October 1st, 2017.

R Core Team (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed May 9 2019.

Medical Services Commission of British Columbia. Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee. Colorectal Screening for Cancer Prevention in Asymptomatic Patients. http://www.bcguidelines.ca/. Published March 1, 2013. Updated June 22, 2016. Accessed May 9 2019.

Leddin D, Armstrong D, Borgaonkar M, et al. The 2012 SAGE wait times program: Survey of Access to Gastroenterology in Canada. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013 Feb; 27(2):83–89.

Harris RP, Sheridan SL, Lewis CL, Barclay C, Vu MB, Kistler CE, Golin CE, DeFrank JT, Brewer NT. The harms of screening: A proposed taxonomy and application to lung cancer screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Feb 1;174(2):281–5.

Acknowledgments

Statistical support was provided through the British Columbia Cancer Agency.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the BC Cancer Agency Research Ethics board on October 6, 2017.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanders, D., Bakos, B., Gentile, L. et al. Premature Fecal Immunochemical Testing in British Columbia Canada: a Retrospective Review of Physician and Screening Participant Characteristics. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 444–448 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05399-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05399-4