Abstract

Background

One widely cited study suggested a link between physician empathy and laboratory outcomes in patients with diabetes, but its findings have not been replicated. While empathy has a positive impact on patient experience, its impact on other outcomes remains unclear.

Objective

To assess associations between physician empathy and glycosylated hemoglobin (HgbA1c) as well as low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels in patients with diabetes.

Design

Retrospective cross-sectional study.

Participants

Patients with diabetes who received care at a large integrated health system in the USA between January 1, 2011, and May 31, 2014, and their primary care physicians.

Main Measures

The main independent measure was physician empathy, as measured by the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE). The JSE is scored on a scale of 20–140, with higher scores indicating greater empathy. Dependent measures included patient HgbA1c and LDL. Mixed-effects linear regression models adjusting for patient sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidity index, and physician characteristics were used to assess the association between physician JSE scores and their patients’ HgbA1c and LDL.

Key Results

The sample included 4176 primary care patients who received care with one of 51 primary care physicians. Mean physician JSE score was 118.4 (standard deviation (SD) = 12). Median patient HgbA1c was 6.7% (interquartile range (IQR) = 6.2–7.5) and median LDL concentration was 83 (IQR = 66–104). In adjusted analyses, there was no association between JSE scores and HgbA1c (β = − 0.01, 95%CI = − 0.04, 0.02, p = 0.47) or LDL (β = 0.41, 95%CI = − 0.47, 1.29, p = 0.35).

Conclusion

Physician empathy was not associated with HgbA1c or LDL. While interventions to increase physician empathy may result in more patient-centered care, they may not improve clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Patient-centered care is increasingly heralded as a strategy to improve both patient experience and outcomes.1 One systematic review concluded that both patient-centered verbal behaviors, such as reassurance and support, as well as nonverbal cues, such as head nodding and forward lean, were associated with higher patient satisfaction and adherence to medical regimens.2 Patient-centered communication has also been reported to improve medication adherence across a variety of specific disease states, including COPD3 and hyperlipidemia,4 as well as within specific patient populations, such as in the elderly.5 Viewed in conjunction with evidence that medication adherence is associated with health,6 this provides a mechanistic link between patient-centered communication and clinical outcomes.7,8

One aspect of patient-centered communication, physician empathy, has been shown to correlate with patient experience measures, making it an area of growing interest for its potential to improve care.9,10 Recently, a retrospective study linked primary care physician empathy with hypertension control, adding evidence to support the hypothesis that physician empathy may directly affect patients’ clinical outcomes.11 There are several ways in which physician empathy has been postulated to affect patient outcomes. A Spanish study postulated that physician empathy may impact access to health services, as they found patients of high-empathy physicians were more likely to see their primary care physician and therefore to also more likely to receive medical attention.12 Another qualitative study concluded when patients feel that their physicians are empathetic, it facilitates their understanding, thereby leading increased adherence to medication regimens.13 As a result, many health systems have adopted interventions aimed at enhancing physician empathy, with the goal of improving patient-centered care as well as patient outcomes.14,15,16,17

Diabetes is highly prevalent among US adults,18 and many patients find it challenging to achieve a good glycemic control.19 Several studies have documented the integral role of patient provider communication in diabetes management,20,21,22 as well as the importance of patient-centered decision-making in diabetes outcomes.23 However, only one study has found a positive association between physician empathy and laboratory outcomes in diabetes. In 2011, Hojat and colleagues reported that physician empathy was associated with glycosylated hemoglobin (HgbA1c) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) in a cohort of diabetic patients and their physicians.24 This study has been widely cited and often used as a rationale for empathy training programs in medicine.25,26 Yet this single-center study included some notable limitations, including a relatively small sample of physicians (n = 29) and patients (n = 891), and accounted for very few potential confounders. As a result, the association between physician empathy and laboratory outcomes in diabetes remained undetermined.

The objective of this study was to assess the association between physician empathy and laboratory outcomes and to replicate the study by Hojat and colleagues in a large, diverse cohort of patients with diabetes and their physicians, controlling for patient and physician characteristics.

METHODS

This is a cross-sectional study of primary care physicians and their patients with diabetes seen at the Cleveland Clinic Health System (CCHS) between January 1, 2011, and May 31, 2014. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Cleveland Clinic.

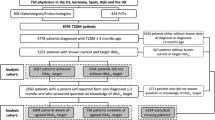

Study Population

This study included practicing primary care physicians and their patients with diabetes. Included physicians were (1) board certified in either Internal or Family Medicine and (2) had at least 45 diabetic primary care patients in their panel. Included patients were those on these physicians’ assigned primary care panels, and (1) between 18 and 75 years, (2) with a diagnostic code for diabetes (either type 1 or 2) in their chart, (3) who had at least two visits with their primary care provider in the past 365 days, and (4) who spent at least 2/3 of their total primary care office visits with their specified provider. These inclusion criteria closely match that reported by Hojat and colleagues in their 2011 study.24

Independent Measure

We used physician empathy scores collected during a mandatory communication skills course conducted at CCHS between August 2013 and May 2014. Course participation was required for all full and part-time physicians. The content and structure of communication skills course has been reported in detail previously.17

At the start of the course, each physician completed the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE), a validated 20-item measure of physician empathy.27,28,29 Items are rated on seven point scales and scores range from 20 to 140, with higher scores indicating greater physician empathy. We analyzed JSE scores two ways: continuously, and in groups using cut-points described by Hojat and colleagues24 of low (< 117), moderate (118–127), and high (≥ 128) empathy scorers.

Dependent Measures

HgbA1c and LDL were considered as markers of diabetes management. We used the last HgbA1c and LDL measurements recorded in the electronic health record (EHR) prior to their physician’s completion of the JSE. We measured laboratory outcomes continuously and dichotomously, as well-managed versus not. Well-managed was defined as < 7.0% for HgbA1c and < 100 mg/dL for LDL, which matched the dichotomization scheme utilized by Hojat and colleagues.24

Control Measures

We included a number of patient and physician characteristics as control measures. For patients, these included age (continuous), sex, race (white, black, and other), marital status (married/domestic partnership or single/separated), body mass index (BMI), Charlson Comorbidity Index, insurance status (private, Medicare, Medicaid, or self-pay), and median annual income (derived from the patient zip code). Physician characteristics included age (continuous), sex, years of experience (continuous), specialty (Internal Medicine or Family Medicine), and physician type (MD or DO). Physician characteristics were provided by the Cleveland Clinic Office of Professional Staff Affairs and all patient data was derived from the EHR.

Statistical Analysis

We generated mixed-effects linear regression models assessing the association between physician empathy and their patients’ HbA1c and LDL, respectively. In these models, both the JSE and laboratory outcomes were treated as continuous measures. Models were clustered by physician and adjusted for the patient and physician measures described above. As a first sensitivity analysis, we reproduced the models five times to specifically assess the association between JSE and laboratory outcomes among patients with more medical comorbidities and/or with more poorly controlled laboratory measures of diabetes. These five models were (1) only patients with a Charlson score greater than or equal to 1, (2) only patients with an HgbA1c > 7.0%, (3) only patients with an LDL > 100, (4) only patients with a Charlson score greater than or equal to 1 and an HgbA1c > 7.0%, and (5) only patients with a Charlson score greater than or equal to 1 and an LDL > 100. As a second sensitivity analysis, we then reproduced the analysis of Hojat and colleagues, using their treatment of variables and covariates. This included ordinal coding of JSE scores as low, moderate, and high and dichotomous HgbA1c and LDL outcomes (well-managed versus not).24 Consistent with their analysis, we used logistic regression, controlling for patient age, sex, and insurance status as well as physician age and sex. All analyses were conducted in R version 3.4.2 (https://cran.r-project.org/).

RESULTS

The sample included 4176 patients and 51 physicians. During the study inclusion period, the median total number of patient visits with their primary care provider was 6 (interquartile range (IQR) = 3–10) and physicians had a median of 89 diabetic patients on their primary care panels. (IQR = 60–116). Approximately half of patients (53%) were male and patients ranged in age from 18 to 75 years (IQR = 55–69). Patients had a median HgbA1c of 6.7% (IQR = 6.2–7.5) and a median LDL concentration of 83.0 mmol/dL (IQR = 66.0–104.0). Sixty-one percent of patients had well-managed HgbA1c and 71% had well-managed LDL. The mean BMI was 34(7.6) and 23% of patients had Charlson scores above 2. Sixty-five percent (n = 33) of physicians were board certified in Internal Medicine, and almost all (94%) physicians were MDs (versus DOs). The median JSE score was 122 (IQR 112–126). Twenty percent of physicians had low empathy, 43% had moderate empathy, and 37% had high empathy. Additional patient and physician characteristics are presented in Table 1.

There were no significant associations between physician empathy scores and HgbA1c or LDL values in the mixed-effects linear regression model (Table 2). Additionally, no other physician characteristics were associated with either LDL or HbgA1c in these models. Certain patient characteristics, including younger age (β = − 0.08, 95%CI = − 0.11, − 0.05), higher Charlson score (β = 0.12, 95%CI = − 0.08, 0.16), higher BMI (β = 0.01, 95%CI = 0.01, 0.02), and male sex (β = 0.16, 95%CI = 0.07, 0.25) were associated with higher HgbA1c, while younger age (β = − 2.29, 95%CI = − 2.89, − 1.70), lower Charlson score (β = − 1.72, 95%CI = − 2.55, − 0.90), Black race (compared to White; β = − 5.82, 95%CI = 2.46, 9.19), and female sex (β = − 10.20, 95%CI = − 12.30, − 8.10) were associated with higher LDL. When the analyses were limited to patients with at least one medical comorbidity and/or poorer laboratory control of their diabetes, there remained no association between empathy score and either A1c or LDL in any of the five sensitivity analysis models.

In logistic regression models replicating the methods of Hojat and colleagues, there were similarly no significant associations between physician empathy and HgbA1c or LDL (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In our study of a large, diverse sample of diabetic patients and their primary care physicians, we found no association between physician empathy as measured by the JSE and HgbA1c or LDL. This lack of an association was consistent in our novel analysis regardless of which patients were included as well as our replication of Hojat and colleagues’ prior methods. Patient demographic and clinical characteristics, however, including BMI and burden of comorbidities, were associated with laboratory outcomes. No physician characteristics were associated with either HgbA1c or LDL values.

Both the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes endorse the use of patient-centered care to optimize health outcomes for diabetic patients.30 Patient-centered communication practices are hypothesized to impact clinical outcomes through a number of pathways including improved decision making, greater patient knowledge and improved adherence, among others.31,32 Physician empathy has been proffered as an important component of patient-centered care,33 and Hojat and colleagues’ study appeared to provide evidence of a direct association between empathy and clinical outcomes in diabetes.24 However, our study in a larger, more recent sample, controlling for important patient and physician factors, casts doubt on this association. That we found no signal of any association suggests that self-reported physician empathy alone is unlikely to have a generalizable impact on laboratory outcomes in diabetes in contemporary practice.

There are several reasons our findings may have differed from the original study. First, our data are considerably newer. It is possible that changes in diabetes treatment guidelines since the original study have eliminated the association between empathy and HgbA1c and LDL. For example, statin prescribing has become more widespread, and there is almost universal recognition of the importance of glycemic control.34,35 In addition, as care pathways have become more prominent, some clinician characteristics, like empathic communication, may now be less strongly associated with clinical outcomes. Furthermore, the recent proliferation of health system performance measurement, and the linking of glycemic control to reimbursement in pay-for-performance contracts, has been linked to reducing variance in outcomes in patients with diabetes36 and may also contribute to the lack of association with clinician characteristics. That our sample, compared to Hojat and colleagues, appeared to have a slightly larger percentage of patients with good management of their HgbA1c and LDL supports these theories. Finally, it is also possible that the settings in which these studies were carried out may also have impacted the associations. For years, the Cleveland Clinic has had care paths for chronic disease management37 as well as a robust system of sharing key performance indicators with both frontline providers and leadership in order to drive improvement in chronic disease management.38 Thus, institution-specific characteristics may also impact the strength of the relationship between individual provider characteristics with clinical outcomes.

One explanation that cannot account for the difference in findings is methodology. Our study closely replicated Hojat’s study in terms of inclusion criteria as well as data analysis. Replication studies are important because they often fail to reproduce initial findings. For decades, scientists in the psychological and clinical sciences have lamented the lack of replication studies,39,40 and have noted that the replication studies that are conducted often times fail to reproduce the results from earlier studies.41,42,43 This has led multiple researchers to claim that most clinical associations reported from single observational research reports are false.42,43,44 They have postulated many reasons that published results are difficult to replicate. These include difficulty controlling for environmental factors that may impact external validity as well as publication bias favoring acceptance of research with type I errors.45,46,47 Publication bias, which favors novel and positive studies, also discourages replication in health services research.48 Moreover, a recent paper documenting the attempts of numerous research teams to answer a single research question using identical data found even slightly different methodological approaches yielded different results, highlighting how analytic plans may contribute to literature agreement.49 However, in addition to more a rigorous analyses, we also attempted to replicate Hojat and colleagues’ analytic approach, using nearly identical inclusion criteria and treatment of variables, and were nonetheless unable to reproduce their findings. This result underscores the importance of conducting multiple studies to confirm observed effects.

The prospect of improving diabetic outcomes through empathy enhancement programs is appealing; a single physician may care for numerous diabetic patients, and enhanced empathy is a relatively low-cost solution for the problem of poor diabetes management.50 However, while empathy might enhance patient experience, it is less clear how a brief empathic encounter can overcome the manifold challenges patients face attempting to control their diabetes outside the physician’s office. In 2012, Hojat and colleagues published another study in an Italian sample, showing that physician JSE scores were associated with the odds of developing diabetes-related complications.51 To date, that 2012 study and the one that we sought to reproduce are the only evidence supporting a link between physician empathy and clinical outcomes in diabetes. That both studies were conducted by members of the same study team underscores the need for further exploration of this association by independent study teams. Indeed, other studies have also failed to demonstrate an association between patient-centered care and diabetic outcomes. One study found that patient-centered communication was associated with improved self-management and quality of life but not glycemic control.52 Another study of over 1300 patients with diabetes in the VA and 42 primary care physicians found that physician-level factors accounted for less than 2% of variability in hgbA1c.53 Physician training programs aimed at enhancing empathy likely result in improved patient experience.9,10,54 However, the impact of such interventions on clinical endpoints in diabetes now appears less likely given the addition of our negative study to a small body of literature in diabetes care that, with the exception of Hojat’s studies, has failed to find an association. This mirrors the state of the literature more broadly, which has long connected physician characteristics with patient satisfaction and trust,10,55,56,57 and suggested that these associations may correlate with clinical outcomes,58 but has not been able to consistently quantify such a link.59

This study had some limitations. First, our analysis, like that of Hojat and colleagues, relied on physician-reported measures of empathy, which may differ from patient perceptions of physician empathy.60,61,62 More broadly, we were only able to assess empathy via the JSE, which may differ from empathic communication or behavior measured by other tools. Second, we used HgbA1c and LDL values closest to the date on which their primary care physician completed the JSE, of which 65%, 84%, and 99% were obtained within 1, 2, and 3 years of the JSE administration, respectively. Hojat and colleagues do not report this information, so it is difficult to compare if the distribution of the timing of the tests differed across our two studies. However, as a sensitivity analysis, we restricted the sample to those with laboratory values within 1 year of their physician’s completion of the JSE, and we found no difference from the results reported here. This was unsurprising, as longitudinal studies of self-reported measures of empathy, like the one used in this study, have suggested empathy scores stabilize around age 17 and remain consistent for decades upon retesting in adult populations.63,64 Additionally, there are multiple studies conducted in healthcare settings that report empathy scores to be fairly consistent over time.65,66,67 Third, we relied on a single laboratory value for LDL and HgbA1c, which may represent a deviation from either a higher or lower value assessed previously. Thus, a single value may fail to capture an important trajectory in an individual patient’s diabetic management. Fourth, our patient population on average had relatively few comorbidities as measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index and had relatively good control of laboratory markers. This might affect the measured association between empathy and A1c as well as LDL, and it is possible it might contribute to differences between the results presented here and those reported by Hojat et al. However, even when the analyses were repeated and limited to sicker patients, the association remained non-significant. Fifth, we did not account for diabetes or cholesterol treatments, which may explain our LDL findings. However, since medications are a powerful tool by which physicians can impact diabetes outcomes, it would be inappropriate to adjust for them. Finally, the reporting of methods by Hojat and colleagues is limited. Thus, while we attempted to replicate their study, it is possible that our methods differed from theirs in ways we are unable to account for.

CONCLUSION

Physician empathy is associated with improved patient experience. To date, evidence supporting the impact of physician empathy on clinical outcomes in diabetes has been limited to a single small study. Using a larger, more contemporaneous sample, we failed to demonstrate an independent association between one survey-based physician empathy score and LDL or HgbA1c in diabetic primary care patients. While interventions to increase physician empathy may improve patient-centered care, our findings suggest they may not result in improved clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes.

References

Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001570.

Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(1):25–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.

Blais L, Bourbeau J, Sheehy O. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD. Trends in patient’s persistence on treatment and determinants of use. Can Respir J. 2003;11:27–32.

Mann DM, Allegrante JP, Natarajan S, Halm EA, Charlson M. Predictors of adherence to statins for primary prevention. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2007;21(4):311–316.

Balkrishnan R. Predictors of medication adherence in the elderly. Clin Ther. 1998;20(4):764–771.

Dimatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002 40:794–811.

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pr. 2000;49(9):796–804.

Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423–1433. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1337906/pdf/cmaj00069-0061.pdf.

Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(3):237–251.

Chaitoff A, Sun B, Windover A, et al. Associations between physician empathy, physician characteristics, and standardized measures of patient experience. Acad Med. 2017: 92:1464-1471. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001671.

Yuguero O, Marsal JR, Esquerda M, Soler-González J. Occupational burnout and empathy influence blood pressure control in primary care physicians. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0634-0.

Yuguero O, Melnick ER, Marsal JR, Esquerda M, Soler-Gonzalez J. Cross-sectional study of the association between healthcare professionals’ empathy and burnout and the number of annual primary care visits per patient under their care in Spain. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e020949.

Gascón JJ, Sanchez-Ortuno M, Llor B, Skidmore D, Saturno PJ. Why hypertensive patients do not comply with the treatment: results from a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2004;21(2):125–130.

Stein T, Frankel RM, Krupat E. Enhancing clinician communication skills in a large healthcare organization: a longitudinal case study. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58(1):4–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.01.014.

Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(7):1310–1318. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0450.

Kelm Z, Womer J, Walter JK, Feudtner C. Interventions to cultivate physician empathy: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):219. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-219.

Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016:31:755-61.

Geiss LS, Kirtland K, Lin J, et al. Changes in diagnosed diabetes, obesity, and physical inactivity prevalence in US counties, 2004-2012. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173428.

Blonde L, Aschner P, Bailey C, et al. Gaps and barriers in the control of blood glucose in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Vasc Dis Res. 2017;14(3):172–183.

Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83–90.

Kruse RL, Olsberg JE, Shigaki CL, et al. Communication during patient-provider encounters regarding diabetes self-management. Fam Med. 2013;45(7):475–483.

Bundesmann R, Kaplowitz SA. Provider communication and patient participation in diabetes self-care. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):143–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.025.

Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):448–457.

Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):359–364. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1.

Chou CL, Cooley L, Pearlman E, White MK. Enhancing patient experience by training local trainers in fundamental communication skills. Patient Exp J. 2014;1(2):36–45.

Hojat M, Axelrod D, Spandorfer J, Mangione S. Enhancing and sustaining empathy in medical students. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):996–1001.

Tavakol S, Dennick R, Tavakol M. Psychometric properties and confirmatory factor analysis of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):54.

Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Mangione S, Vergare M, Magee M. Physician empathy: definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1563–1569. http://graphics.tx.ovid.com/ovftpdfs/FPDDNCGCGFLABD00/fs026/ovft/live/gv007/00000465/00000465-200209000-00016.pdf.

Hojat M. Empathy in Patient Care: Antecedents, Development, Measurement, and Outcomes. New York: Springer; 2007.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes: A Patient-Centered Approach: Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364–1379. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0413.

Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015.

Zolnierek KBH, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826–834. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc.

Epstein RM, Street RL. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100–103. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1239.

Jensen MD, Donna Ryan C-CH, Caroline Apovian C-CM, Jensen MD, et al. AHA/ACC/TOS Obesity Guideline 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults ACCF/AHA TASK FORCE MEMBERS Subcommittee on Prevention Guidelines. 2013.

Salami JA, Warraich H, Valero-Elizondo J, et al. National trends in statin use and expenditures in the US adult population from 2002 to 2013: insights from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Jama Cardiol. 2017;2(1):56–65.

Van Herck P, De Smedt D, Annemans L, Remmen R, Rosenthal MB, Sermeus W. Systematic review: effects, design choices, and context of pay-for-performance in health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):247.

Rundall TG, Shortell SM, Wang MC, et al. As good as it gets? Chronic care management in nine leading US physician organisations. BMJ Br Med J. 2002;325(7370):958.

Wadsworth T, Graves B, Glass S, Harrison AM, Donovan C, Proctor A. Using business intelligence to improve performance: Cleveland Clinic tracks KPIs daily to measure progress toward achieving the organization’s strategic objectives. This effort has helped reduce labor costs and other expenses--and improve quality of care. Healthc Financ Manag. 2009;63(10):68–73.

Smith NC. Replication studies: A neglected aspect of psychological research. Am Psychol. 1970;25(10):970.

Moonesinghe R, Khoury MJ, Janssens ACJW. Most published research findings are false—but a little replication goes a long way. PLoS Med. 2007;4(2):e28.

Ioannidis JPA, Ntzani EE, Trikalinos TA, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG. Replication validity of genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2001;29(3):306–309.

Grimes DA, Schulz KF. False alarms and pseudo-epidemics: the limitations of observational epidemiology. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):920–927.

Ioannidis JPA, Chen J, Kodell R, Haug C, Hoey J. Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. PLoS Med. 2005;2(8):e124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124.

Young SS, Karr A. Deming, data and observational studies. Significance. 2011;8(3):116–120.

Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1261–1267.

Franco A, Malhotra N, Simonovits G. Publication bias in the social sciences: Unlocking the file drawer. Science (80- ). 2014;345(6203):1502–1505.

Simmons JP, Nelson LD, Simonsohn U. False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychol Sci. 2011;22(11):1359–1366.

Martin GN, Clarke RM. Are psychology journals anti-replication? A snapshot of editorial practices. Front Psychol. 2017;8.

Silberzahn R, Uhlmann EL, Martin D, et al. Many analysts, one dataset: Making transparent how variations in analytical choices affect results. 2017.

Bommer C, Heesemann E, Sagalova V, et al. The global economic burden of diabetes in adults aged 20–79 years: a cost-of-illness study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(6):423–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30097-9.

Del Canale S, Louis DZ, Maio V, et al. The Relationship Between Physician Empathy and Disease Complications. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1243–1249. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628fbf.

Williams JS, Walker RJ, Smalls BL, Hill R, Egede LE. Patient-Centered Care, Glycemic Control, Diabetes Self-Care, and Quality of Life in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18(10):644–649. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2016.0079.

Tuerk PW, Mueller M, Egede L. Estimating physician effects on glycemic control in the treatment of diabetes: methods, effects sizes, and implications for treatment policy. Diabetes Care. 2008.

Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(606):76–84. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X660814.

Jackson JL, Chamberlin J, Kroenke K. Predictors of patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(4):609–620.

Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296–306. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090205.

Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282(6):583–589.

Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Patient satisfaction and quality of care. Mil Med. 1997;162(4):273–277.

Reid RO, Friedberg MW, Adams JL, McGlynn EA, Mehrotra A. Associations between physician characteristics and quality of care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(16):1442–1449.

Hojat M, Louis DZ, Maxwell K, Markham F, Wender R, Gonnella JS. Patient perceptions of physician empathy, satisfaction with physician, interpersonal trust, and compliance. Int J Med Educ. 2010;1:83.

Kane GC, Gotto JL, West S, Hojat M, Mangione S. Jefferson Scale of Patient’s Perceptions of Physician Empathy: preliminary psychometric data. Croat Med J. 2007;48(1):81–86.

Bernardo MO, Cecílio-Fernandes D, Costa P, Quince TA, Costa MJ, Carvalho-Filho MA. Physicians’ self-assessed empathy levels do not correlate with patients’ assessments. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0198488.

Taylor SJ, Barker LA, Heavey L, McHale S. The longitudinal development of social and executive functions in late adolescence and early adulthood. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:252.

Lawrence EJ, Shaw P, Baker D, Baron-Cohen S, David AS. Measuring empathy: reliability and validity of the Empathy Quotient. Psychol Med. 2004;34(5):911–920.

Lor KB, Truong JT, Ip EJ, Barnett MJ. A randomized prospective study on outcomes of an empathy intervention among second-year student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(2):18.

Quince TA, Parker RA, Wood DF, Benson JA. Stability of empathy among undergraduate medical students: a longitudinal study at one UK medical school. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):90.

Nakano EV. The effect of clinical experience on perceived and self-reported empathy in novice speech-language pathology clinicians. 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Cleveland Clinic.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chaitoff, A., Rothberg, M.B., Windover, A.K. et al. Physician Empathy Is Not Associated with Laboratory Outcomes in Diabetes: a Cross-sectional Study. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 75–81 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4731-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4731-0