Abstract

Background

Hospitalization offers smokers an opportunity to quit smoking. Starting cessation treatment in hospital is effective, but sustaining treatment after discharge is a challenge. Automated telephone calls with interactive voice response (IVR) technology could support treatment continuance after discharge.

Objective

To assess smokers’ use of and satisfaction with an IVR-facilitated intervention and to test the relationship between intervention dose and smoking cessation.

Design

Analysis of pooled quantitative and qualitative data from the intervention groups of two similar randomized controlled trials with 6-month follow-up.

Participants

A total of 878 smokers admitted to three hospitals. All received cessation counseling in hospital and planned to stop smoking after discharge.

Intervention

After discharge, participants received free cessation medication and five automated IVR calls over 3 months. Calls delivered messages promoting smoking cessation and medication adherence, offered medication refills, and triaged smokers to additional telephone counseling.

Main Measures

Number of IVR calls answered, patient satisfaction, biochemically validated tobacco abstinence 6 months after discharge.

Key Results

Participants answered a median of three of five IVR calls; 70% rated the calls as helpful, citing the social support, access to counseling and medication, and reminders to quit as positive factors. Older smokers (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.20–1.54 per decade) and smokers hospitalized for a smoking-related disease (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.21–2.23) completed more calls. Smokers who completed more calls had higher quit rates at 6-month follow-up (OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.30–1.70, for each additional call) after multivariable adjustment for age, sex, education, discharge diagnosis, nicotine dependence, duration of medication use, and perceived importance of and confidence in quitting.

Conclusions

Automated IVR calls to support smoking cessation after hospital discharge were viewed favorably by patients. Higher IVR utilization was associated with higher odds of tobacco abstinence at 6-month follow-up. IVR technology offers health care systems a potentially scalable means of sustaining tobacco cessation interventions after hospital discharge.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers NCT01177176, NCT01714323.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States,1 and nearly four million smokers are hospitalized annually.2 Hospitalization requires temporary tobacco abstinence, providing patients an opportunity to quit smoking. Illness may also enhance motivation to quit.2 Tobacco cessation interventions that start in the hospital are associated with increased cessation rates, but to be effective, they must sustain treatment for more than a month after discharge.2 This evidence led the Joint Commission to adopt a tobacco cessation quality measure for U.S. hospitals in 2012 that was endorsed by the National Quality Forum in 2014.3 , 4 The measure requires hospitals to document all admitted patients’ smoking status and to offer smoking cessation counseling and pharmacotherapy both in the hospital and at discharge.

Hospitals have not generally translated this evidence into routine practice. A particular challenge is linking smokers to ongoing cessation support after hospital discharge.2 Delivering post-discharge cessation counseling by telephone is effective,2 but not widely adopted due to expense. A potentially cost-effective, scalable alternative uses interactive voice response (IVR) technology to automate post-discharge telephone calls.5 , 6 By substituting a computer for a human caller, an IVR system can make multiple calls both during and outside normal business hours and initiate contact soon after discharge when patients are at high risk of relapse. IVR can provide targeted motivational messages to promote self-efficacy, quit attempts, and smoking cessation medication adherence, and can facilitate medication refills to ensure a full course of treatment. It can improve the efficiency of telephone counseling by identifying the subset of smokers likely to benefit, and connect these smokers to live counselors.

IVR systems have been used in smoking cessation interventions in inpatient and outpatient settings,5 – 9 including a tobacco cessation intervention for smokers admitted to Canadian hospitals.10 We adapted that model to create a multi-component intervention that facilitated the delivery of counseling and pharmacotherapy to smokers for 3 months after hospital discharge. We tested two versions of this model in two randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The IVR components were similar across trials, differing only in how smokers seeking additional support were subsequently connected to live telephone counseling. In the single-site Helping HAND [Hospital-initiated Assistance for Nicotine Dependence] 1 (HH1) RCT in 397 hospitalized smokers, the IVR system prompted a hospital-based counselor to call patients within 48 h. This intervention increased biochemically validated smoking cessation by 71% at 6-month follow-up compared to standard post-discharge care (26% vs. 15%, relative risk 1.71, 95% CI 1.14–2.56).11 In the multi-site Helping HAND 2 (HH2) RCT of 1357 hospitalized smokers, participants seeking additional support during an IVR call were transferred directly to a telephone quitline, a free, nationally accessible scalable cessation resource. The HH2 intervention improved smoking cessation rates at 3 months, but 6-month results did not differ.12 A possible explanation for this difference is that in HH2, fewer smokers who requested additional counseling during an IVR call actually reached a counselor.12 Contrary to expectation, connecting smokers directly to a community-based quitline was cumbersome and was less successful in engaging smokers in counseling than having hospital-based staff make a separate call to smokers.12

Nonetheless, the IVR interventions themselves, including call scripts and schedules, were nearly identical. To increase statistical power and generalizability, this report pools data from the two trials to describe the IVR system’s feasibility and acceptability for patients and to examine the association between IVR dose received and smoking cessation success. We hypothesized that smokers completing more IVR calls would have a higher smoking cessation rate at 6-month follow-up.

METHODS

Setting and Subjects

The Helping HAND trials were two similar randomized controlled trials testing the effectiveness of post-discharge smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized adult cigarette smokers who planned to stop smoking after discharge.11 , 12 HH1 (2010–2012) was conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH; Boston, MA).11 HH2 (2012–2015) was conducted at MGH, North Shore Medical Center (Salem, MA), and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (Pittsburgh, PA).12 Both studies were approved by the Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Board and registered with the National Institutes of Health ClinicalTrials.gov registry (NCT01177176, NCT01714323). Detailed study protocols were published previously.13 , 14

In both studies, inpatient tobacco counselors saw hospitalized smokers to encourage cessation. They referred patients who met study eligibility criteria to study staff, who obtained informed consent, conducted the baseline assessment, and assigned participants to a study condition. Adults (≥18 years old) were eligible if they were current daily smokers, received inpatient smoking cessation counseling, and stated that they planned to quit or try to quit smoking after discharge. Participants were randomly assigned to standard care (control) or sustained care (intervention) groups, stratified by daily cigarette consumption (< 10 vs. ≥ 10) and admitting service (cardiac vs. other). This report pools data from the intervention groups of both trials.

Intervention

At discharge, intervention participants were registered with the IVR vendor (TelASK Technologies, Ottawa, Canada) using a web interface and given a free 30-day supply of their choice of any U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved cessation medication (refillable twice). Participants received five tailored outbound automated IVR calls scheduled at 2, 14, 30, 60, and 90 days post-discharge. For each call, the IVR system made eight attempts to reach participants at their choice of a land line or cell phone number over 4 days.

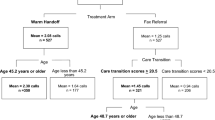

Each IVR call lasted 1–2 min. It assessed a participant’s current smoking status, intention to quit or confidence in staying quit, current smoking cessation medication use, and desire for additional telephone counseling support or medication refill (Fig. 1). Prerecorded motivational messages, tailored to participants’ responses, encouraged participants to stay quit or make another quit attempt, promoted the use of smoking cessation medication, and offered to triage smokers to a counselor for additional cessation support. In HH1, trained hospital-based counselors made the return calls, using a standardized counseling protocol, aimed at increasing medication adherence and helping prevent relapse or restarting quit attempts.13 In HH2, participants were connected to a counselor at a commercial quitline vendor, who offered similar options. Participants could request counseling during any IVR call, but the IVR script also encouraged participants to speak with a counselor if they had low confidence in their ability to stay quit, resumed smoking but still wanted to quit, needed a medication refill, had problems with their study-prescribed medication, or stopped using medication before completing a full course. To encourage participants to answer incoming IVR calls, the caller identification was the name of the hospital, and participants received written information with expected call dates. Participants were required to answer IVR calls to request free medication refills or access a human counselor.

Measures/Assessments

Baseline measures included demographic factors, health insurance, number of cigarettes per day, nicotine dependence (time to first cigarette after waking15), prior use of tobacco cessation treatment, perceived importance of and confidence in quitting (10-point Likert scales), post-discharge intention (quit vs. try to quit), presence of another smoker at home, and a screen for alcohol abuse (AUDIT-C).16 Hospital records provided primary discharge diagnosis and length of stay.

Participants were called 1, 3, and 6 months after discharge to assess tobacco use and smoking cessation treatment use. The primary outcome was biochemically validated past-7-day tobacco abstinence at 6 months, defined as abstinence from any tobacco product. Participants’ self-reported abstinence was validated with a mailed saliva sample for assay of cotinine, a nicotine metabolite, or in-person exhaled air carbon monoxide (CO) measurement.17 Self-reported abstinence was verified if cotinine was ≤10 ng/ml or CO < 9 ppm.18

At follow-up, participants were asked three questions about their satisfaction with the IVR intervention: (1) “How helpful was it to get phone calls to check in about your smoking after you left the hospital?” (5 options, very helpful to not at all helpful); (2) “If a friend or family member who smokes and wanted to stop were hospitalized, would you recommend that they be followed by an automated telephone support system to help them stop smoking?” (5 options, strongly recommend to strongly not recommend); and (3) an open-ended question asking what was and was not helpful about the automated telephone support.

The number of IVR calls answered by each participant was measured using records from the IVR provider. Calls were considered completed if the recipient answered the first question, which asked about smoking status.

Analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and included participants randomly assigned to the intervention (sustained care) groups of both trials. We calculated the proportion of IVR calls that were answered across participants and the average number answered per participant. We conducted bivariate and multivariable analyses to identify the characteristics and post-discharge treatment utilization for participants who completed more than the median number of IVR calls. We tested the hypothesis that more calls would be associated with greater smoking cessation using multiple logistic regression models. Patients with missing outcomes or whose self-reported abstinence was not biochemically validated were counted as smokers. Biochemically validated 6-month abstinence was the dependent variable. Number of completed IVR calls was the primary independent variable. We adjusted for age, sex, race, education, study (HH1 or HH2), discharge diagnosis (smoking-related vs. not), nicotine dependence, importance of and confidence in quitting, and duration of cessation medication use. We tested for an interaction between number of IVR calls and study cohort (i.e., HH1 or HH2) to examine whether the effect of the IVR calls differed by the counselor to whom smokers were connected (i.e., hospital-based vs. quitline-based).

Participants’ responses to an open-ended question about what they liked and did not like about the IVR calls were analyzed qualitatively by identifying pervasive themes. A coding rubric with multiple categories was developed to account for all responses. Two coders independently coded responses into these categories, then discussed and resolved discrepancies. Inter-rater reliability, using Cohen’s kappa, was 0.79.

RESULTS

Recruitment and Retention

Of the 1756 patients enrolled in the two trials (n = 397 in HH1, n = 1359 in HH2), 879 were randomly assigned to the intervention groups (n = 198 in HH1, n = 680 in HH2) between August 2010 and July 2014.11 , 12 HH1 achieved higher follow-up completion rates than HH2: 90% vs. 82% at 1 month, 83% vs. 76% at 3 months, and 83% vs. 75% at 6 months (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Seventeen intervention group patients (2%) died during follow-up. Among self-reported nonsmokers at 6 months in HH1 and HH2, 79% and 68%, respectively, provided a biological sample for confirmation. Abstinence was confirmed in 86% and 72% of these samples. Detailed information about clinical follow-up was reported previously.

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics for the intervention groups of the two studies are displayed in Table 1. The samples differed in multiple factors. The median hospital stay was 4–5 days (IQR, 3–7 days).

Utilization of the IVR Intervention

In both studies, participants were scheduled to receive five IVR calls each. Excluding canceled calls, 2574 (61%) of 4189 IVR planned calls were completed. Fewer planned calls were completed in HH2 than in HH1 (59% vs. 70%, p < 0.0001). In both trials, the proportion of participants who completed a call declined with elapsed time post-discharge; 72% of calls were completed at day 2, 69% at day 12, 62% at day 28, 54% at day 58, and 48% at day 88. Participants completed a median of three of five calls (IQR 2–4). One-quarter of participants (25%) answered all five calls, 42% answered four or more, 62% answered three or more, and only 12% answered no calls.

In univariate analyses, participants who completed 4–5 IVR calls versus 0–3 calls were more likely to be older and to have a smoking-related or circulatory disease discharge diagnosis, but did not differ significantly on other factors (Table 2). In a multivariable logistic regression analysis that adjusted for sex, race, and education, completing more IVR calls was associated with older age (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.20–1.54, for each decade), a smoking-related discharge diagnosis (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.21–2.23), and study cohort (OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.45–2.86, for HH1 vs. HH2; Table 2). A circulatory disease discharge diagnosis was also associated with completing more IVR calls (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.16–2.14) when substituted for smoking-related disease in this multivariable model.

At every IVR call, participants were offered to be connected with a counselor who could provide support and refill medications. Participants requested connection at 1154 (43%) of 2655 IVR calls answered. The request rate was higher in HH1 (339/670, 51%) than in HH2 (823/1985, 41%; p < 0.01). Over 95% of participants chose to use nicotine replacement therapy after discharge, most commonly nicotine patch with or without an oral formulation. A medication refill was requested during 803 (30%) of 2655 completed IVR calls, while counseling was requested in 578 (22%). Fewer participants requested a medication refill in HH1 (27%, 180/670) than in HH2 (31%, 623/1985; p < 0.05), while more participants requested a counselor in HH1 (25%, 167/670) than in HH2 (21%, 411/1985; p < 0.05). During follow-up, participants who completed 4–5 calls versus 0–3 calls were also more likely to use counseling (56% vs. 35%; p < 0.0001) or cessation medication for >1 month (91% vs. 75%; p < 0.0001).

Satisfaction with IVR Calls

Participants were generally satisfied with the IVR calls: 75% of HH1 participants and 69% of HH2 participants (70% overall) rated the IVR system as very or somewhat helpful. Ninety percent of HH1 participants and 82% of HH2 participants (84% overall) said they would recommend the program to family or friends who smoked. Four hundred thirty participants (49%) provided open-ended comments about which IVR properties they found most helpful. Comments were grouped into categories as follows: (1) IVR calls acted as a reminder to quit, (2) the check-in made them feel accountable for quitting, (3) the calls offered social support for quitting, (4) they offered access to live counseling, (5) they provided access to medication refills, and (6) IVR calls were convenient and easy to use (Table 3). Four hundred twenty-two participants identified characteristics of the IVR calls that were not helpful (Table 4). A small proportion of respondents did not like receiving automated calls, did not want any help, or stated that the calls came at inconvenient times, but most complaints related to the system’s functionality in the HH2 trial. Many participants in that study stated that the process required to reach a counselor at the quitline was cumbersome.

Tobacco Cessation

Across both studies, 164 intervention group participants (18.7%) had biochemically verified past-7-day abstinence at 6 months after discharge. In a multiple logistic regression analysis that adjusted for age, sex, race, education, duration of cessation medication use after discharge, and study cohort (HH1 vs. HH2), participants who completed more IVR calls were more likely to be abstinent at 6 months (OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.30–1.70 for each additional call completed; Table 5). Other factors independently associated with greater tobacco cessation success were lower nicotine dependence, a smoking-related discharge diagnosis, perceiving greater importance in quitting, having more confidence in the ability to quit, using cessation medication for more than 30 days after discharge, and enrollment in HH1 (vs. HH2). The association persisted when we substituted baseline plan to quit for confidence in quitting in the analysis. The interaction between number of IVR calls and study cohort was not significant. The association between number of IVR calls completed and cessation success was also observed when the HH1 and HH2 trials were analyzed separately (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This analysis of data from two large randomized trials of hospitalized smokers found that automated phone calls using IVR technology were a feasible and acceptable means of delivering smoking cessation support after hospital discharge. Smokers answered most calls and reported that they liked how IVR calls reminded them to stay quit, made them feel accountable, offered social support, and facilitated access to additional tobacco cessation medication and counseling. IVR is also more resource-efficient for health systems than having staff conduct calls.

The study found a strong dose–response relationship between the number of IVR calls answered and cessation success at 6 months. This association is consistent with, but does not prove, a causal relationship. It could also occur if participants who were a priori more likely to quit answered more IVR calls or if participants who relapsed stopped taking calls. Because the dose–response relationship remained significant after adjustment for baseline assessments of nicotine dependence, a smoker’s plan to quit, confidence in ability to quit, importance of quitting, and presence of a smoking-related disease, the multivariable analysis does not support the alternative explanation that smokers who were more likely to quit answered more IVR calls. However, we cannot exclude unmeasured confounding.

Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies using IVR calls to maintain contact with patients outside of traditional health care settings and to triage at-risk patients to auxiliary services.19 – 26 IVR has also been used successfully as a tool for recruiting smokers into tobacco cessation treatment,27 – 29 but IVR calls have been less successful in increasing quit rates in purely outpatient settings.7 – 9

Our study, like others,22 , 28 found that older smokers and those with a smoking-related disease answered a greater number of IVR calls. These smokers may be more motivated to quit, more often at home to receive calls after discharge, or more likely to answer the telephone. Younger smokers may prefer post-discharge contact by text message rather than phone calls. Future interventions might add other communication modalities to IVR technology. Patient acceptance of IVR calls decreased between HH1 and HH2, despite similar efforts to maximize response rates. Whether the difference between the 2010 and 2014 studies was attributable to a decline in smokers’ willingness to accept telephone calls, a difference in study populations, or another cause is uncertain. Rates of response to telephone polls have been shown to decline over time,30 but we know of no data on response rates to IVR calls over time. Even with the lower response rates in HH2 compared to HH1, 59% of IVR calls in the second trial were completed.

The strengths of this study include its large sample size, multiple hospitals, and the integration of quantitative and qualitative data. The study design does not allow us to determine, however, whether IVR calls would be associated with cessation success without the offer of free cessation medication or if the intervention were provided to smokers not interested in quitting. Overall, our findings demonstrate that IVR technology offers health care systems a feasible, acceptable way to sustain tobacco cessation treatment after hospital discharge. The next question is whether IVR systems will be adopted for routine care delivery. The Medical University of South Carolina has done so.31 IVR technology can also help hospitals meet the Joint Commission’s tobacco cessation quality measures, which require hospitals to connect smokers to cessation support after discharge.3 , 4 Currently, these measures are optional. Making them required might encourage adoption of IVR systems. Hospitals also have a less tailored, cheaper option for meeting the measures. They can refer inpatients directly to state-sponsored telephone quitlines that are free and available to any smoker.32 However, the effectiveness of quitlines for sustaining cessation after hospital discharge has yet to be demonstrated.33 , 34 The primary issue for health system adoption is whether the extra costs of IVR are worth the extra benefits (if shown) compared to free quitlines. Research is needed to compare the cost-effectiveness of quitlines and IVR systems so that hospitals can make an informed choice in how to meet tobacco quality measures and contribute to reducing the burden of tobacco-related disease.

References

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/index.html. Accessed April 28, 2017. NBK179276 [bookaccession].

Rigotti NA, Clair C, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:001837.

Fiore MC, Goplerud E, Schroeder SA. The Joint Commission’s new tobacco-cessation measures--will hospitals do the right thing? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(13):1172–1174.

National Quality Forum. NQF endorses behavioral health measures. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/news_and_resources/Press_Releases/2014/NQF_endorses_behavioral_health_Measures.aspx. Published March 7, 2014. Updated 2014. Accessed May 8, 2017.

Reid RD, Pipe AL, Quinlan B, Oda J. Interactive voice response telephony to promote smoking cessation in patients with heart disease: a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(3):319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.01.005.

Regan S, Reyen M, Lockhart AC, Richards AE, Rigotti NA. An interactive voice response system to continue a hospital-based smoking cessation intervention after discharge. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011.

McNaughton B, Frohlich J, Graham A, Young QR. Extended interactive voice response telephony (IVR) for relapse prevention after smoking cessation using varenicline and IVR: a pilot study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:824–2458–13-824.

Papadakis S, McDonald PW, Pipe AL, Letherdale ST, Reid RD, Brown KS. Effectiveness of telephone-based follow-up support delivered in combination with a multi-component smoking cessation intervention in family practice: a cluster-randomized trial. Prev Med. 2013;56(6):390–397.

McDaniel AM, Vickerman KA, Stump TE, et al. A randomised controlled trial to prevent smoking relapse among recently quit smokers enrolled in employer and health plan sponsored quitlines. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e007260–2014-007260.

Reid RD, Mullen KA, Slovinec D’Angelo ME, et al. Smoking cessation for hospitalized smokers: an evaluation of the "Ottawa Model". Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(1):11–18.

Rigotti NA, Regan S, Levy DE, et al. Sustained care intervention and postdischarge smoking cessation among hospitalized adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(7):719–728.

Rigotti N. A., Tindle HA, Regan S, et al. A post-discharge smoking cessation intervention for hospital patients: Helping HAND 2 randomized clinical trial. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):597–608.

Japuntich SJ, Regan S, Viana J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of post-discharge interventions for hospitalized smokers: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:124.

Reid ZZ, Regan S, Kelley JH, et al. Comparative effectiveness of post-discharge strategies for hospitalized smokers: study protocol for the helping HAND 2 randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1484-015-1484-0.

Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, FagerstrÖm KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127.

Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795.

SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(2):149–159.

Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(1):13–25.

Cohen-Cline H, Wernli KJ, Bradford SC, Boles-Hall M, Grossman DC. Use of interactive voice response to improve colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 2014;52(6):496–499.

Heyworth L, Kleinman K, Oddleifson S, et al. Comparison of interactive voice response, patient mailing, and mailed registry to encourage screening for osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(5):1519–1526.

Piette JD, Weinberger M, McPhee SJ. The effect of automated calls with telephone nurse follow-up on patient-centered outcomes of diabetes care: a randomized, controlled trial. Med Care. 2000;38(2):218–230.

Piette JD, Rosland AM, Marinec NS, Striplin D, Bernstein SJ, Silveira MJ. Engagement with automated patient monitoring and self-management support calls: experience with a thousand chronically ill patients. Med Care. 2013;51(3):216–223.

Rose GL, MacLean CD, Skelly J, Badger GJ, Ferraro TA, Helzer JE. Interactive voice response technology can deliver alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(4):340–344.

Forster AJ, Boyle L, Shojania KG, Feasby TE, van Walraven C. Identifying patients with post-discharge care problems using an interactive voice response system. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):520–525. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0910-3.

Graham J, Tomcavage J, Salek D, Sciandra J, Davis DE, Stewart WF. Postdischarge monitoring using interactive voice response system reduces 30-day readmission rates in a case-managed medicare population. Med Care. 2012;50(1):50–57.

Ritchie C, Richman J, Sobko H, Bodner E, Phillips B, Houston T. The E-coach transition support computer telephony implementation study: protocol of a randomized trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(6):1172–1179.

Carlini BH, McDaniel AM, Weaver MT, et al. Reaching out, inviting back: using interactive voice response (IVR) technology to recycle relapsed smokers back to quitline treatment—a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:507.

Carlini B, Miles L, Doyle S, Celestino P, Koutsky J. Using diverse communication strategies to re-engage relapsed tobacco quitline users in treatment, New York state, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E179.

Haas JS, Linder JA, Park ER, et al. Proactive tobacco cessation outreach to smokers of low socioeconomic status: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):218–226.

Pew Research Center. Assessing the Representativeness of Public Opinion Surveys. May 12, 2012. Available at: http://www.people-press.org/2012/05/15/assessing-the-representativeness-of-public-opinion-surveys/. Accessed May 8, 2017.

Nahhas GJ, Wilson D, Talbot V, et al. Feasibility of implementing a hospital-based "opt-out" tobacco cessation service. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016; published online December 29, 2016. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw312. Accessed May 8, 2017.

Tindle HA, Daigh R, Reddy VK, et al. eReferral between hospitals and quitlines: an emerging tobacco control strategy. Am J Prev Med. 2016; 51:522–526.

Cummins SE, Gamst AC, Brandstein K, et al. Helping Hospitalized Smokers: A Factorial RCT of Nicotine Patches and Counseling. Am J Prev Med. 2016; 51:578–586.

Rigotti NA, Stoney K. CHARTing the Future Course of Tobacco-Cessation Interventions for Hospitalized Smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2016; 51:549–55.

Acknowledgements

TelASK Technologies of Ottawa, Canada, developed and provided the IVR services. The quitline services were provided by Alere Wellbeing, Inc. We thank our research staff, including Molly Korotkin, BA, Joseph Viana, BA, and Michele Reyen, MPH, for their assistance in conducting the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

NIH/NHLBI grants #1RC1-HL99668 and #1R01-HL11821.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Rigotti has received a research grant from and been an unpaid consultant for Pfizer regarding smoking cessation. She receives royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Park has a grant from Pfizer to provide free varenicline for use in a trial funded by NCI. Dr. Singer has been a paid consultant to Pfizer on topics other than smoking cessation. All other authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rigotti, N.A., Chang, Y., Rosenfeld, L.C. et al. Interactive Voice Response Calls to Promote Smoking Cessation after Hospital Discharge: Pooled Analysis of Two Randomized Clinical Trials. J GEN INTERN MED 32, 1005–1013 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4085-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4085-z